The current monkeypox outbreak in multiple countries outside endemic regions has highlighted the limited knowledge of risk of transmission from infected patients in healthcare settings to others, including patients and healthcare personnel (HCP). Understanding the risk of transmission, and specifically the types of exposures in healthcare settings that may confer higher risk, is essential for infection prevention and control strategies, as well as to inform recommendations for postexposure monitoring and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP). Transmission to HCP in endemic settings is well described, Reference Nakoune, Lampaert and Ndjapou1,Reference Beer and Rao2 but to date it appears to be rare in well-resourced settings. In this rapid literature review, we identified published studies of cases of monkeypox outside endemic regions where nosocomial exposure was described. We found a single documented transmission event; however, variable definition of exposure and limited specific details of the circumstances leading to exposure highlight the need for additional efforts to define and characterize exposures to monkeypox in healthcare settings.

Methods

We performed searches of PubMed and Embase in May 2022, supplemented by a manual search by a medical librarian. No limit on language was imposed. The search combined the concepts of monkeypox, disease transmission, and humans. It excluded studies exclusively set in endemic regions, literature reviews, and studies published prior to the year 2000. The Embase search strategy is available upon request, and the PubMed search was conducted using the following strategy: ((monkeypox[title] OR “monkey pox”[title] OR “Monkeypox”[Mesh] OR “Monkeypox virus”[Mesh]) AND (“transmission”[Subheading] OR epidemiology[subheading] OR “Disease Transmission, Infectious”[Mesh] OR transmit*[tw] OR spread[tw] OR outbreak*[tw] OR cases[tw] OR case[tw] OR imported[tw]) AND (humans[mesh] OR “health personnel”[mesh] OR human[tw] OR humans[tw] OR person[tw] OR persons[tw] OR traveler[tw] OR travelers[tw] OR travelled[tw] OR traveled[tw] OR patient[tw] OR patients[tw] OR healthcare[tw] OR “health care”[tw]) NOT (“Africa”[Mesh] NOT (“Americas”[Mesh] OR “Asia”[Mesh] OR “Europe”[Mesh] OR “Oceania”[Mesh]))) AND 2000/01/01:2022/12/31[dp] NOT review[pt].

Our review was restricted to studies that identified nosocomial exposures and subsequent management. Studies that described monkeypox cases in ambulatory clinics, emergency departments, and inpatient settings that did not comment on HCP exposure were excluded. For each publication, we extracted the definition of exposures, when provided, the total number of HCP exposed, and assessment of monkeypox infection among those exposed (symptom monitoring or serological analyses).

Results

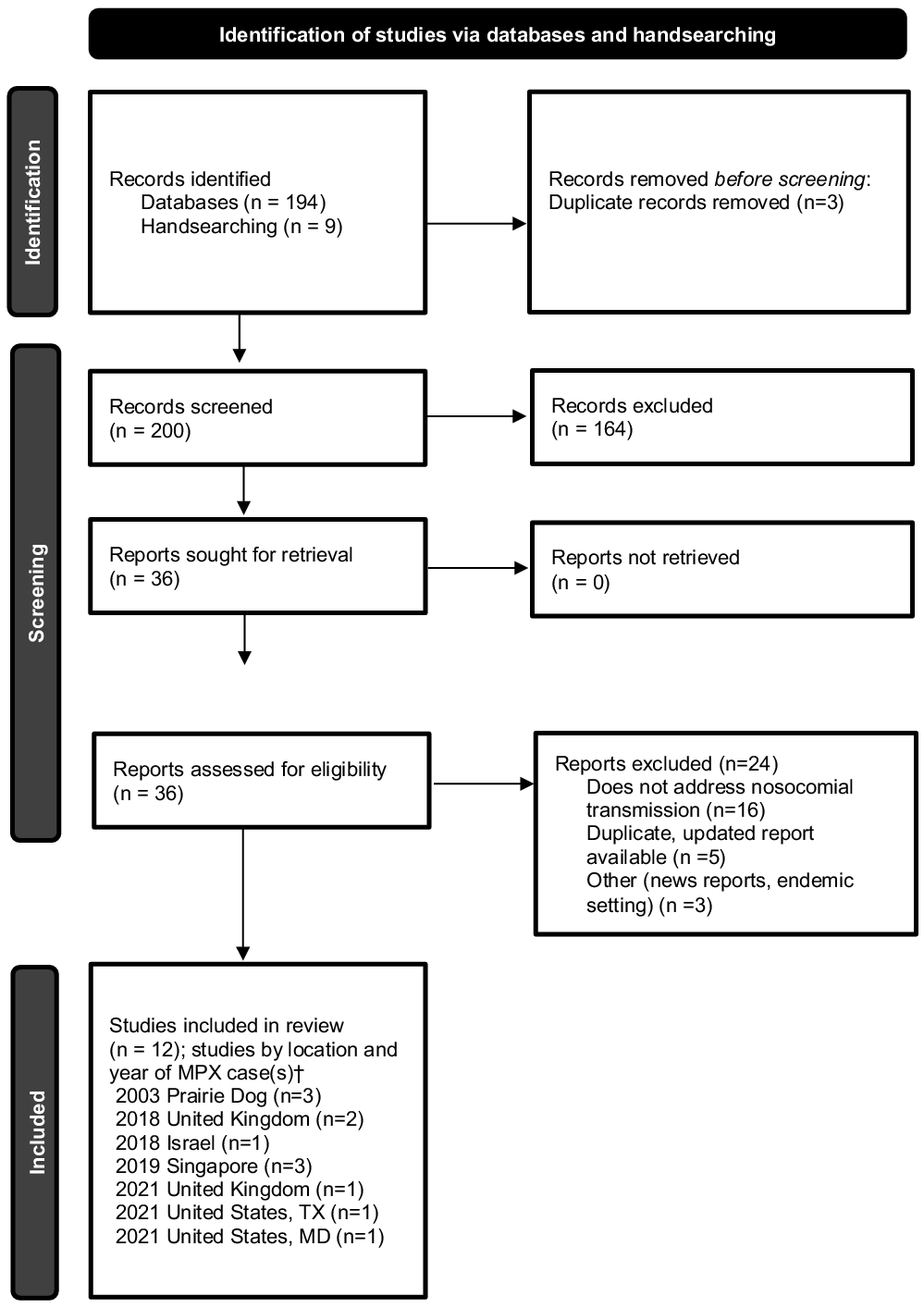

The search yielded 194 publications, and an additional 9 studies were manually selected, for a total of 203 studies for screening. After the removal of 3 duplicates, 200 studies were screened, of which 164 were excluded. Among 36 studies assessed for eligibility through full-text review, 24 were excluded, leaving a total of 12 studies for inclusion (Fig. 1). Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt3 Of the 12 studies included, multiple studies described the same cases or outbreak and were combined in the analysis when details from >1 publication were within the scope of review.

Fig. 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart. Identification of studies, screening, and inclusion criteria are provided. The numbers of studies are listed.

†Multiple studies may have been included describing the same case(s).

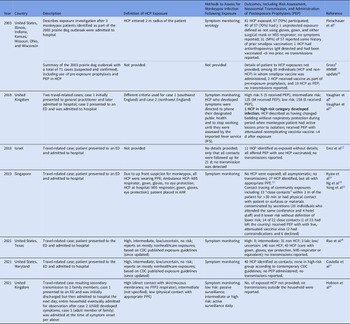

Between 2000 and 2022, not including the current outbreak, we identified cases of monkeypox that were diagnosed outside endemic regions and were cared for in healthcare settings that reported exposure of HCP and subsequent evaluation. These cases were identified as part of the 2003 prairie dog–associated outbreak in the United States and, between 2018 and 2021, from outbreaks in the United Kingdom, Israel, Singapore, and the United States, in travelers returning from endemic areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Healthcare-Associated Monkeypox Exposures, Management, and Risk of Transmission in Nonendemic Countries, 2000–2022

Note. HCP, healthcare personnel; HCF, healthcare facility; AIIR, airborne infection isolation room; PEP, postexposure prophylaxis with vaccine; ED, emergency department; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PPE, personal protective equipment; FFP3 respirator, filtering facepiece respirator class P3.

Definitions of exposures varied across reports, as did descriptions of personal protective equipment (PPE) used and risk stratification of exposed HCP. Symptom monitoring, both active and passive, was the most employed method to detect infection following exposure, and one study employed serological analysis in a subset of HCP. Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) with vaccine was offered and administered in a subset of exposures. A single case of healthcare-associated transmission was described in an HCP in the United Kingdom. This exposure was deemed high risk due to changing presumably contaminated bedding while wearing disposable apron and gloves but not a face mask or respirator, during a period when the patient had active lesions prior to isolation. This HCP received PEP with live, attenuated vaccinia virus (Modified Vaccinia Ankara, MVA-BN, Bavarian Nordic, marketed as IMVANEX in Europe, JYNNEOS in the United States, and IMVAMUNE in Canada) 5–7 days after multiple exposures and developed illness 8 days after receiving vaccine. Reference Vaughan, Aarons and Astbury4

Discussion

We undertook a rapid review of the literature to characterize, in nonendemic countries, the reported risk of patient-to-HCP exposure and transmission in healthcare facilities. Despite documented exposures in such settings, only a single transmission event has been reported. These findings are subject to important limitations, including variable definitions of exposure, rendering it difficult to quantify exposed HCP across published reports or to ascertain risk stratification among those exposed. Additionally, the granular details of each exposure (PPE worn by source and exposed, types of interactions that took place, and duration) are not available. Contact tracing and exposure investigations are resource intensive and rely upon potentially imperfect recollection from interviewed HCP. These practical challenges hinder the collection of data necessary to stratify risk and to comprehend more fully the nature of exposures in healthcare settings.

Proposed exposure definitions, which encompass both healthcare and nonhealthcare settings, have been developed by the UK Health Security Agency 5 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 These definitions are not concordant in terms of risk stratification, recommendations for PEP, or work restrictions for HCP. Consensus definitions would allow not only for improved understanding of risk of exposure from specific interactions and modifiers of risk but also for comparisons across countries investigating exposures. Any exposure framework must include specific definitions of degree of risk based on the nature of source-exposed interactions (ie, direct or indirect contact, intact vs nonintact skin, mucous membranes) and the PPE worn by both the source (eg, face mask) and those exposed (eg, gown, gloves, face mask, N95 respirator or equivalent, eye protection).

In summary, based on published reports prior to the May 2022 global outbreak of monkeypox in nonendemic countries, the risk of exposure in well-resourced healthcare settings leading to transmission is low, with a single reported transmission event in the current literature. These findings may inform the provision of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which has been recommended not only for laboratory personnel working with or performing diagnostic testing for orthopoxviruses and HCP who administer ACAM2000 (Smallpox [Vaccinia] Vaccine, Live) but also for HCP designated by public health authorities as response team members and for HCP who care for patients infected with orthopoxviruses. Reference Rao, Petersen and Whitehill7 The literature, however, is limited both in scale and in the details required to effectively categorize risk. Evaluations of nosocomial exposures during the current outbreak may provide additional information regarding the risk of exposure in healthcare facilities, which would in turn provide information on both PrEP and PEP strategies, though comparisons across care settings will likely be hindered by inconsistent exposure definitions and risk classification.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Lisa L. Philpotts, RN, MSLS, of the Treadwell Library at Massachusetts General Hospital for assistance with literature search strategy and Sharon B. Wright, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Lahey Health, for her thoughtful review and comments.

Financial support

This work was supported by US Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (grant no. 6 U3REP150548-05-08 to ESS) and department funds (K.Z.).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.