Theobalds, the creation of Sir William Cecil (1520/1–98), first Baron Burghley, has long been a spectral presence in the history of Elizabethan country houses. From the time of its completion in 1585 until the time of its destruction shortly after 1650, less than seventy years passed. During that period, Theobalds gained a reputation throughout Europe, befitting its status as the principal country home of Elizabeth I's principal minister and, from 1607, a major early Stuart royal palace. It was the country house most favoured by Queen Elizabeth, and was visited by all the major court and political figures of the Elizabethan, Jacobean and Caroline periods. It was here that King James I was received by the royal household and court on his journey south from Scotland in 1603, and here that he died in 1625, his son Charles being proclaimed king at the palace's gates.

In architectural terms, Theobalds, which was located near Cheshunt in Hertfordshire, was hugely innovative and influential. Lord Burghley used the house as a platform to demonstrate his power, taste and knowledge, lavishing money on its building and decoration. At Theobalds, architectural features including balconies and compass windows made some of their earliest documented appearances in English architecture, while the house was rivalled by none for its number of loggias, long galleries and rooftop walks. Theobalds set new standards in its scale, plan, style and fitting out, and was imitated in numerous late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century buildings in England and further afield. Most famously, these include Holdenby in Northamptonshire (1571–83) and Audley End in Essex (c. 1604–14) – both later adopted as royal palaces – but the information set out in this article helps to show that Theobalds's plan and architecture also influenced houses including Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire (1580–88), Knole in Kent (as rebuilt c. 1604–08), and Hatfield in Hertfordshire (1607–12). It would be no exaggeration to state that Theobalds was probably the most significant country house of the Elizabethan period. As a result, new discoveries relating to it have the potential to contribute to our knowledge of architecture of the whole era.

To date, Theobalds has attracted only limited scholarly attention, based on a belief that – as the house was demolished so long ago – its appearance and plan could never be accurately reconstructed. Certainly, it is true that only few traces of this remarkable building survive today,Footnote 1 and there are no known contemporary depictions of the house, aside from a handful of designs and two rough and inaccurate sketches.Footnote 2 Yet, in comparative terms, Theobalds is extraordinarily well documented, and the phases of its design and construction can be reconstructed with some confidence. The first scholar to attempt this was Sir John Summerson, who published a seminal article in 1959.Footnote 3 Since then, further work has been published on the years when Theobalds served as a royal palace,Footnote 4 on its architectural influence,Footnote 5 its gardens and landscape setting,Footnote 6 and its decorative schemes.Footnote 7 However, the majority of the primary evidence relating to Theobalds remains unexplored, and there are major aspects of the house which have yet to be investigated. Most notably, its plan has not been established beyond the general details set out by Summerson and then repeated, with further observations, by Ian Dunlop.Footnote 8

This article aims to reconstruct the plan of Theobalds, using evidence provided by primary sources such as the Cecil Papers at Hatfield House, the Royal Works accounts, descriptions of visitors, and the detailed parliamentary survey of April 1650. No inventories recording the contents of the house are known to survive, but the layout of Theobalds is further illuminated by a unique series of documents, all clearly authored by Lord Burghley. These are schedules showing how Queen Elizabeth, her attendants and courtiers were to be accommodated at the house for the royal visits of 1572, 1577, 1583 and 1591.Footnote 9 Although these sources have generally been very little studied, they were used by Summerson. However, his work focused on the development, phasing, design process, overall layout and general appearance of Theobalds. In his article of twenty pages, only around four described the house's ‘interior disposition’.Footnote 10 Summerson readily acknowledged the limited scope of his paper: he noted that the parliamentary survey, for instance, provided more information, ‘but there would be no point in cataloguing these details in a paper which aims only at a general architectural description’.Footnote 11

Here, Summerson's findings have been taken further and extended through a more detailed study of the primary material relating to the house's plan and decoration, including some sources that were not used (or at least cited) by Summerson.Footnote 12 The full value of these sources, especially the schedules of accommodation and the parliamentary survey, has been exploited here for the first time. While the outcome is not a comprehensive reconstruction of every detail of the plan of Theobalds, it is more than any other scholar has achieved so far. Indeed, this article shows that, far from being poorly understood, the plan of Theobalds is perhaps better documented than that of any other Elizabethan courtyard house of its status.

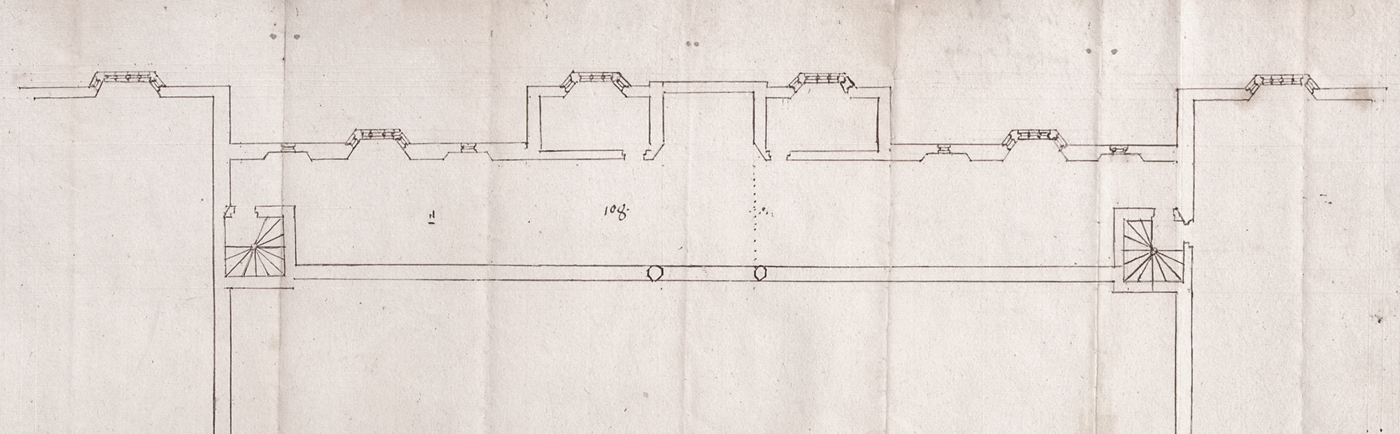

This article focuses on the two principal courtyards of Theobalds – the Middle Court and Conduit Court – the ranges of which included the public rooms and lodgings. The rooms' positions and arrangements will be the emphasis, but their decoration will also be touched upon. Although no contemporary upper-floor plans of Theobalds as built are known to survive,Footnote 13 there are drawings by John Thorpe of c. 1606, showing most of the ground floor (Fig. 1) and basement as completed.Footnote 14 Together with the large body of primary evidence, these allow for conjectural reconstructions of all of Theobalds's floor levels (Figs 2–6), attempted here for the very first time.Footnote 15 A reconstruction of the house's exterior has also been attempted (Fig. 7).Footnote 16

Fig. 1. John Thorpe's ground-floor plan of Theobalds, c. 1606 (courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane's Museum): north to right. The Middle Court is shown below and the Conduit Court above. Some of the planted grids of the Privy Garden (north) and Maze Garden (west) are included in the drawing.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction plan of the ground floor of Theobalds, based on the survey by John Thorpe (© Historic England, Philip Sinton). In this and the other reconstruction plans, only the house's two main courtyards are shown, along with the projecting range at the south-east

Fig. 3. Conjectural reconstruction plan of the first floor of the Middle Court of Theobalds (© Historic England, Philip Sinton)

Fig. 4. Conjectural reconstruction plan of the first floor of the Conduit Court and the second floor of the Middle Court of Theobalds (© Historic England, Philip Sinton). The areas shaded in dark grey represent leaded walks

Fig. 5. Conjectural reconstruction plan of the attic/tower floor of the Middle Court of Theobalds (© Historic England, Philip Sinton). The darker shading represents roofs that formed leaded walks, though that on the east of the Middle Court was at a lower (second-floor) level and that on the north of the Conduit Court was at first-floor level. The roof of the projecting gallery range appears to have been pitched and tiled

Fig. 6. Conjectural reconstruction plan of the attic/tower floor of the Conduit Court of Theobalds (© Historic England, Philip Sinton). The shading represents roofs that formed leaded walks, though that on the north was at a lower (first-floor) level

Fig. 7. Conjectural reconstruction of the exterior of Theobalds, viewed from the south-east, showing the principal courtyards, projecting gallery range, Base Court and some of the gardens (© Historic England, Allan Adams)

Theobalds is notable as a house that was designed, in particular, to reflect the tastes and requirements of the itinerant monarch and royal court.Footnote 17 At home and abroad, the house was known to people who moved in the highest circles, a number of whom visited it and recorded their impressions. It was host to Queen Elizabeth in at least eleven different years, making it her most visited house outside the royal palaces.Footnote 18 It later proved as popular with James I. The king appears to have made a total of nine visits before 22 May 1607, when Theobalds became royal property.Footnote 19 Especially notable was James's visit of 24–28 July 1606, when he was accompanied by his brother-in-law, King Christian IV of Denmark, and members of the Danish royal court. From 1607 onwards, King James spent a large amount of time at Theobalds, as did his son Charles. No wonder that, despite the house's ‘verrie good repaire’, the parliamentarians chose to demolish the building, which for three generations had stood as a prominent symbol of the power of royalty and the wealth and influence of the English elite.Footnote 20

SUMMARY OF THE HOUSE'S HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

Theobalds (also known as Thibaulds, Theballs, Tibols and Tybolles) was acquired in 1564 by Sir William Cecil, apparently with the intention of creating a future home for his younger son, Robert, born the preceding year.Footnote 21 At that point, the estate included a moated manor house. This building, which Cecil seems to have upgraded by the addition of a parlour with a great chamber above, accommodated Queen Elizabeth on her visit of July 1564.

Almost immediately, Cecil began to build a new house on a site three-quarters of a mile to the north-east. This seems initially to have included a single main courtyard, the site of which was later occupied by Theobalds's Conduit Court. Clearly, this house proved inadequate, and plans for expansion were probably in hand by 1566. A drawing endorsed by Cecil makes clear that a new second courtyard, to the east of the old court, was to be the point of entry, and that a hall was to be located in a new dividing range. The hall range had been initiated by 1567 and was completed in 1569–70, with a stone loggia and frontispiece on the east façade. We know this was executed by Hans Hendrik van Paesschen, a mason from Antwerp who built Sir Thomas Gresham's Royal Exchange (1566–70), the first major Renaissance-style building in the City of London.Footnote 22

A plan that survives in the Thorpe collection in Sir John Soane's Museum is clearly a design for the new courtyard and it (or the drawing on which it is based) is likely to date from c. 1567.Footnote 23 By 1568/69, work was probably under way on the north, south and east ranges of this courtyard, which came to be known as the Middle Court or Inner Court (until the 1580s) and Second Court (from the 1580s). This phase of building must have been largely complete by September 1571, when Queen Elizabeth made her first known visit to the new Theobalds. Certainly, the north and south ranges were finished in time for the royal visit of July 1572, although the east range – which is documented in surviving designs (Figs 8 and 9) – was apparently only completed in 1573/74.

Fig. 8. Plan of the east (gatehouse) range of the Middle Court of Theobalds, c. 1570 (Hatfield House Archives, Cecil Papers 143/48; courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury): north to left. The drawing probably represents the ground floor, but could also illustrate the first floor, and may not be as executed

Fig. 9. Design for the courtyard façade of the east (gatehouse) range of the Middle Court, possibly in the hand of Lord Burghley, c. 1570 (HHA, CP 143/50; courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury). The façade was altered in execution; for instance, there were only three balconies at first-floor level in the range as completed

There appears to have been almost no let-up in the process of construction. Driven in part by his new status – Cecil was made first Baron Burghley in 1571 and Lord Treasurer in 1572 – and in part by the queen's favour of Theobalds, Cecil pushed ahead with a new round of work. This included the addition of a projecting gallery range, to the south-east of the Middle Court, a design for which survives (Fig. 10). This three-storey range seems to have been completed in 1573/74 and was in full use for the royal visit of 1577.Footnote 24

Fig. 10. Design for the west façade of the projecting gallery range, probably in the hand of Lord Burghley, c. 1572 (HHA, CP 143/41-42; courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury)

Meanwhile, Lord Burghley began to rebuild the ‘old’ courtyard on the west. This appears to have been something of a labour of love, taking over ten years to complete and resulting in Theobalds's most extravagant interiors. Notably, a design for the rebuilding of this courtyard – known as the Conduit or Fountain Court – survives, dated 1572, in the hand of Henry Hawthorne.Footnote 25 Hawthorne was an employee of the Royal Works who seems to have served as Lord Burghley's architect until at least 1577, when his position was taken over by another royal officer, John Symons. Although a later plan by John Thorpe (see Fig. 1) shows that the courtyard was altered in execution, the original vision – that is, of a square court with corner pavilions or towers – endured throughout the design process.

Construction of the Conduit Court was probably begun later in 1572 and was well under way by September 1575. Two years after, payments were made to workmen including a glazier, painter and plasterer.Footnote 26 The three new ranges around the courtyard seem to have been structurally complete by 1578, when chimneys were made and glass with ‘diverse armes' installed.Footnote 27 The ranges were fitted out over the next few years: the chimneypiece and glass were added to the new great chamber in 1582, the glass to the great staircase in the same year, and the north parlour was brought to final completion in 1585.Footnote 28 Elizabeth I declared herself delighted with the work: on 2 June 1583, Roger Manners reported that she ‘was never in any place better plesed, and sure the howse, garden and walks may compare with any delicat place in Itally’.Footnote 29

The completion of the Conduit Court was the last substantial work undertaken at Theobalds by Lord Burghley. Indeed, it was the last substantial work undertaken in the house's history. Following his father's death in August 1598, Sir Robert Cecil (1563–1612) made a number of changes to the house (discussed below), but these seem to have been comparatively minor in nature. It is possible to be more categorical about the alterations carried out after 1607, since detailed accounts of the Royal Works survive. Over these years, various changes were made, but the integrity of the Elizabethan house remained. Thus, the house recorded in such detail in the parliamentary survey of 1650 is largely the Theobalds completed by Lord Burghley in the 1580s.

THEOBALDS UNDER SIR WILLIAM CECIL, LORD BURGHLEY (1564–98)

As has been outlined, there were two key stages in the architectural development of Theobalds: the building of the Middle Court and projecting gallery range (c. 1567–74), and the rebuilding of the Conduit Court (c. 1572–85). Before the completion of the Conduit Court, Theobalds was already fully functional, with the wide range of rooms and lodgings expected of a house of its status. The addition of the Conduit Court extended the house's accommodation to levels usually associated with royal palaces. The plan of these two courtyards will now be explored.

Middle Court

Having gained access to the Middle Court via the gatehouse on its east side, visitors to Theobalds in the mid-1570s would have found themselves in an area 110 ft (33.5 m) square (see Figs 1, 2 and 7).Footnote 30 Aside from the eastern gatehouse range – which was of two storeys with a flat roof – the courtyard ranges rose through three main storeys. In the north and south ranges, the levels must have been relatively low, especially on the ground and first floors, since they were matched in height by the two main levels of the hall range to the west. The roofs of all three ranges were, like that of the eastern block, flat with leaded walks. At the four corners of the Middle Court there were towers, while there were additional turrets at the centres of the two side ranges. At the courtyard's south-east corner, a narrow range projected into the Great Garden. This was also of three storeys, and seemingly had a tower at its southern end.

The east façade of the hall range featured an elaborate stone frontispiece, which formed a five-bay loggia at ground-floor level. On either side of the loggia were bay windows, lighting the upper end of the hall and the winter parlour respectively. At upper-floor level, the frontispiece formed an external walkway, which gave access to an arch containing ‘verrie manie faire curious paintinges and gildinges of pictures [probably carvings], whereof two are called the pictures of Peace and Warre’.Footnote 31 Above, the range's roof was flat, serving as an additional walkway.Footnote 32 At its centre was a timber lantern ‘of excellent workemanshipp curiouslie wrought’, containing a chiming clock.Footnote 33

Facing the hall, on the inside of the gatehouse range, was another loggia, this one of seven bays, with turret staircases at each end. The wall on the loggia's east side contained windows overlooking the Dial or Base Court – the first of Theobalds's main courtyards, forming the approach to the house. In projecting bays either side of the gateway were two rooms, that on the south serving as the porter's lodge (see Fig. 8).Footnote 34 Above was a long gallery, with windows opening on to balconies (see Fig. 9).

Importantly, when it comes to the courtyard façade of the south range, a design appears to survive (Fig. 11). This drawing, included in Thorpe's book and associated with a contemporary plan, was identified by Summerson as being related to Theobalds.Footnote 35 It certainly conforms with much that is known about the house. For instance, the cross-section on the right seems to show the great hall with cellar below, while that on the left represents the intersection of the south range with the lower gatehouse block. At the centre of the range is a columned doorway with a bay window above; such a doorway is shown in this position on Thorpe's ground-floor plan (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 11. Drawing by John Thorpe of an unnamed house, identified as being a design for the courtyard façade of the south (state) range of Theobalds's Middle Court (courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane's Museum). It is probably a copy by Thorpe of an original design dating from c. 1567. The design was altered in execution

In certain other respects, however, the design was clearly altered in execution: a floor level was added above the great hall, and the roofs of all the courtyard's ranges were flat rather than pitched. The form of the windows may have changed also: the lawyer Roger Wilbraham, who visited Theobalds in 1599, reported of the Middle Court: ‘the windowes beneth but one light, those above 2 lightes without transome, and compassed at the top’.Footnote 36 Compass windows were bay windows usually having a semi-circular profile. The earliest, securely dateable, extant example is that on the north front of Burghley House, which is dated 1587, so those at Theobalds must have been an innovation.Footnote 37 Although Wilbraham's description may relate to the range's garden front, it seems certain that the drawing in Thorpe's book must represent an early proposal, perhaps of c. 1567. It is the only evidence we have as to the possible appearance of the courtyard's state range – and also the range to the north, presumably designed in a matching style.

Ground Floor

The principal entrance to Theobalds's interior was via the arch at the centre of the loggia of the hall range. According to the parliamentary survey, lead pipes fed two cisterns in ‘two peeces’ of this arch, probably basins on either side.Footnote 38 As is known from Thorpe's ground plan (see Fig. 1), the door led directly into the screen passage, with the great hall on the south and the Conduit Court on the west. The survey records that – like most of the ‘polite’ rooms at Theobalds – the hall's walls were wainscotted, and its screen was timber, bearing a dial and coat of arms (undoubtedly those of Cecil); this was topped by a minstrels' gallery or ‘clockloft’.Footnote 39 In medieval tradition, the hall was high, rising through the equivalent of ground, first and second floors of the Middle Court. It had an oriel window at its south-east and from its upper end was overlooked by an opening, set in a ‘wainscott case wrought and carved’, accessible from the great staircase (see Fig. 11).Footnote 40 The room was paved and had a chimneypiece of blue marble. An account shows that in 1585 ‘Jenings’ was paid ‘to tryck out England on ye Hall wall in whyt and black’ and ‘to mak ye fram for ye chart of England’.Footnote 41 ‘Tricking’ was a method of indicating the tinctures (or colours) in a coat of arms by the use of abbreviations or symbols, so Jenings – if not a painter himself – was perhaps preparing the heraldic decoration for the painter and ensuring it was accurate.

According to the survey, the hall boasted an elaborate roof, ‘arrched over at the top with curved timber of curious workemanshipp’.Footnote 42 As there was a long gallery above the hall (see below), this cannot have been a timber roof of standard design and construction, like that shown in the drawing of c. 1567 (see Fig. 11). The timberwork can only have been decorative, positioned beneath a flat ceiling. The result must have been something like the great hall at Longleat in Wiltshire (as reworked in the early 1570s) and the slightly later great hall at Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire (Fig. 12), both of which have non-structural hammerbeam trusses with a chamber above (the ‘Prospect Room’ in the case of Wollaton).Footnote 43

Fig. 12. The roof of the great hall at Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire (built 1580–88; © Country Life). The hammerbeam trusses are decorative rather than structural, as there is another chamber (the ‘Prospect Room’) above the hall. The roof may have been influenced by that of the great hall at Theobalds

At the low end of the hall, beyond the screen passage, were the pantry and buttery, with the usual triple door arrangement, but most of the service rooms were at basement level, the great kitchen and pastry rising up through the ground floor also (see Fig. 2). This left space for a winter parlour, which by 1650 was known as the ‘King's waiters’ chamber’; it contained a chimneypiece of grey Sussex marble, with an overmantel bearing a coat of arms (presumably those of Cecil).Footnote 44 Seemingly, the room was equal in height to the ground and first floors of the Middle Court's side ranges, and it had a large bay window, looking east. Here, the Cecils would have dined and entertained on an informal basis, and the schedule of accommodation for the royal visit of 1572 confirms that the room was to be used for the ‘Lord Treasurer's table’ – that is, as Burghley's dining chamber.Footnote 45

The winter parlour was situated close to the ‘north stairs’, which rose in a parallel position to the great stairs on the south. Thorpe's plan shows that these two staircases were of similar arrangement, with quarter landings (see Fig. 1). The north stairs led to the Cecils’ second-floor lodgings and the long gallery over the hall, as well as to the lead walk on the west side of the hall and the walk on top of the hall range, which – after 1585 – provided access to the leads of the Conduit Court.

On the south, adjacent to the great staircase, was the great parlour. This had a bay window overlooking the Great Garden and, like the winter parlour, seems to have risen through the equivalent of two storeys of the Middle Court. Used as the queen's waiters’ room by 1650, the parlour featured a chimneypiece ‘cut into Antickes and other wilde beasts’, with jambs of blue marble.Footnote 46 Schedules of accommodation show that, during Queen Elizabeth's visits, the room was used as her presence chamber (for receptions and audiences), with the great hall serving as great or guard chamber.Footnote 47 Beneath was a colonnaded wine cellar, apparently a space of some grandeur.Footnote 48

The great parlour was linked to the chapel, positioned at the west end of the south range and also accessible directly from the Middle Court (see Figs 1 and 2). The chapel's east end was placed beneath an upper closet, the point of division being marked by a ‘good faire lettis wainscott’ screen.Footnote 49 According to the parliamentary survey, its walls were ‘full of scripture verses, callenders and direccons for morning and evening prayer, Monthes of the yeare Degrees of Marriage the Raigne of the kinges of England and the like’, while the windows were painted. Box pews were arranged ‘college-style’, separated by a central aisle.Footnote 50

The remainder of the ground floor of Theobalds's south range was accessed directly from the courtyard. To the east of the chapel were two good-sized rooms with a back staircase between them, leading to the first-floor lodgings and state apartment above. The room next to the chapel was the chaplain's chamber,Footnote 51 while the chamber to the east, beyond the back stair, housed Lord Burghley's wardrobe and, on at least one royal visit, the Queen's Robes.Footnote 52 The room at the east end of the south range was also used for the Queen's Robes during visits; this had a bay window and was associated with an inner closet.Footnote 53

In the comparable position at the east end of the north range – also with a bay window – was the steward's chamber, used during royal visits as the plate house.Footnote 54 The function of the other rooms on the ground floor of the north range is not clear, since they were not named or allocated in schedules of accommodation. Thorpe's plan (see Fig. 1) shows that the area included at least three fair-sized chambers, one having a bay window overlooking the Privy Garden. Given their proximity to service rooms – including the pastry and privy kitchen – it is likely that these served as the lodgings or workrooms of upper members of Burghley's household.

First Floor

As has been stated, the major rooms of the hall range seem to have risen through ground- and first-floor levels. Meanwhile, on both south and north sides of the Middle Court, the first floors comprised lodgings intended for the Cecils’ relatives, friends and guests. In reconstructing the layouts of these rooms, the schedules of accommodation are invaluable.

On the north, there were four sets of lodgings (see Fig. 3). In the early seventeenth century, almost certainly in altered form, they served as the apartment of the Prince of Wales. This was probably because they were associated with the Green Gallery on the south-east, a long gallery being considered a highly desirable component of any state apartment by the Jacobean period, especially in a royal palace.Footnote 55 Each lodging – a term usually used to describe a bedchamber and pallet chamber – was accessible via a separate staircase, as was conventional for the time. That at the west seems to have been situated adjacent to the north stairs, above the great kitchen. It was occupied during the 1572 royal visit by Edward de Vere (1550–1604), seventeenth Earl of Oxford, Burghley's ward and the husband of his eldest daughter, Anne (1556–88). The main room was also known as ‘the La of Oxfordes Chamber’ and Lady Vere's Chamber or Nursery, reflecting its use by Elizabeth de Vere (1575–1627), born at Theobalds and brought up by her grandparents.Footnote 56

To the east, beneath the rooms of Lord Burghley, was a lodging used by – and named after – Edward Manners (1549–87), third Earl of Rutland, another of Burghley's wards.Footnote 57 Beyond this was a lodging described as being ‘over ye pve kytene’, which occupied the east half of the range at basement level.Footnote 58 Finally, to the east of this, was a comparatively large lodging – comprising a chamber, inner chamber and pallet chamber – which seems to have enjoyed access to the Green Gallery on the south-east. This lodging was occupied by Lord Burghley himself during the royal visit of 1572, when his own rooms were given over to the queen. In 1591, it was used by Sir Walter Raleigh (1554–1618).Footnote 59

The equivalent lodgings in the south range were higher in status; they overlooked the Great Garden and lay beneath the state apartment. However, they were smaller in extent, since the west part of the range contained the upper chapel and chapel closet. Adjacent to this closet was the first of three sets of lodgings. Located beneath Queen Elizabeth's bedchamber, it included a room known as the ‘Lord Keeper's Chamber’, so presumably it had at some point accommodated Burghley's brother-in-law, Sir Nicholas Bacon (1510–79).Footnote 60 During royal visits, the room was used by the queen's attendants, and it was still the ‘Maide of Honors chamber’ in 1650.Footnote 61 A staircase in this general area is shown on Thorpe's ground plan (see Fig. 1), and this would have connected the lodging to the state apartment above.

On the immediate east was a chamber which took its name from Ambrose Dudley (c. 1530–90), third Earl of Warwick, a royal official and brother of the Earl of Leicester. Warwick was married to one of Queen Elizabeth's most favoured attendants, Anne (1548/9–1604), née Russell, and other intimate royal aides occupied the room in later years. Finally, the lodging at the east end of the south range – with a bay window overlooking the Dial Court – was known as the ‘Lord Admiral's Chamber’ by at least 1572, taking its name from Edward Clinton (1512–85), first Earl of Lincoln.Footnote 62 As with Lord Warwick, Lincoln was married to an aide of the queen, Elizabeth (1527–90), n ée FitzGerald.

From c. 1574, this area of the house was associated with the first-floor lodgings in the projecting gallery range. These were three in number, and were similarly intended for guests of high status. They were each separately accessed by staircases on the east, adjacent to the Dovehouse Court. The lodging at the far end of the range – ‘in a tower’ – was the largest, with a chamber and two pallet chambers.Footnote 63 In 1577 and 1583, this was allocated to the queen's cousin Henry Carey (1526–96), first Baron Hunsdon, and in 1591 it was used as the dining room of Robert Devereux (1565–1601), second Earl of Essex, whose main rooms were on the floor above.Footnote 64

Close to all these lodgings was the long gallery on the upper storey of the gatehouse range, accessible via stair turrets at each end of the loggia. The gallery was probably accessible from the first-floor lodgings to north and south, although there is no conclusive evidence of this. The room, completed in 1573/74, was known as ‘ye paynted Gallory’ or, by at least 1607–09, as the Green Gallery.Footnote 65 In the parliamentary survey of 1650, the room was described as being 109 ft (33.2 m) long and 12 ft (3.7 m) wide, with two freestone chimneypieces. The gallery had windows opening on to the Middle Court, with ‘three Belconie doors’, demonstrating that the surviving elevation drawing was altered in execution (see Fig. 9). On the east side were further windows opening on to ‘two small stone Belconies’.Footnote 66 These formed part of the central section of the gallery, which jutted out towards the Dial Court (see Figs 3 and 8).

The earliest known detailed description of the Green Gallery's interior is that of Jacob Rathgeb, secretary to the Duke of Wirtemberg, who visited Theobalds in 1592. He recalled a ‘hall’ containing depictions of ‘the kingdom of England, with all its cities, towns and villages, mountains and rivers; as also the armorial bearings and domains of every esquire, lord, knight, and noble who possesses lands and retains to whatever extent’.Footnote 67 Eight years later, Baron Waldstein stated that the room featured

the coats-of-arms of the earls and barons of England: all round the walls are trees painted in green, one tree for every county in England, and from their boughs hang the arms of those earls, barons, and nobles who live in that particular county. The specialities of any county are included ….Footnote 68

Further information was supplied by Frederic Gerschow, secretary to the Duke of Stettin-Pomerania, who visited in 1602 and described the gallery as displaying ‘all England, represented by 52 trees, each tree representing one province’.Footnote 69 In the parliamentary survey of 1650, the gallery was stated to have been ‘latelie divided into fower lodginge Roomes, and two lobbies’; this probably happened after 1640, when Johann Albrecht de Mandelslo visited and described the room's decoration without noting any subdivision.Footnote 70

First and foremost, the Green Gallery's interior reflected Lord Burghley's interest in pedigrees, which was in evidence throughout Theobalds. Burghley is likely to have been responsible for the gallery's scheme; a drawing by him, showing trees hung with empty shields for coats of arms and banners bearing the names of various Cecils, must give an impression of the finished result (Fig. 13). As well as coats of arms, however, it is clear that the scheme included geographical and cartographic information, another area in which Burghley was interested and involved. He was apparently an active supporter of Christopher Saxton, who carried out the first cartographic survey of England and Wales, producing a series of thirty-four maps engraved between 1574 and 1578. A collection of early proofs of Saxton's maps – with Burghley's annotations – survives, bound up with other maps as his own personal atlas of England and Wales (Fig. 14).

Fig. 13. Detail of a drawing by Lord Burghley showing the genealogy of the Cecils depicted on shields and banners hung on branches (HHA, CP 143/12–13; courtesy of the Marquess of Salisbury). The drawing may give an impression of the interior decoration of the Green Gallery at Theobalds

Fig. 14. Christopher Saxton's map of Northumberland, as published in 1579, with annotations by Lord Burghley, from Burghley's personal atlas (BL Royal 18 D. III, ff. 71v–72; © The British Library Board)

The contemporaneity between Saxton's survey and the decoration of the Green Gallery is notable, the survey of England having been completed by March 1574.Footnote 71 Thus, the gallery's decorative scheme would have been innovative – drawing upon the first accurate maps of the country – and of great interest and use to Burghley, his peers and the queen herself. It also served to represent the greatness of England and Wales, an appropriate theme given that the gallery seems to have served as a ‘show room’ for visitors.

Second Floor, Attics and Towers

In the Middle Court at Theobalds, as at great houses such as Hampton Court (1514–29), status was expressed vertically: the most important rooms on both the south and north sides were at the highest (second-floor) level. The house's first, and – until the 1580s – only, state apartment was on the south, running eastwards from the top of the great staircase (see Fig. 4). The convenience and success of the apartment is proven by the fact that it continued to be used by Queen Elizabeth even after the completion of the much grander suite in the Conduit Court.Footnote 72 One of the advantages of this earlier suite may have been its height, and therefore its distance: for Elizabeth, comparative inaccessibility was an advantage, and it also aided tight security.

The first room of the suite was the great or dining chamber, later known as the queen's presence chamber. This was clearly used by Lord Burghley as his own great chamber, while during royal visits the room became Queen Elizabeth's privy chamber, used for her private dining.Footnote 73 According to the parliamentary survey, the great chamber was wainscotted, ‘floored with spruce deale boordes, of a good scent’, and had a large window overlooking the Great Garden. Its stone chimneypiece was ‘excellentlie well carved’, and featured a device, in that it bore a black marble bowl fed with water.Footnote 74

Adjoining the great chamber on the north was a lobby, this containing an open wainscot case ‘wrought and carved to looke downe into ye hall’.Footnote 75 Another lobby, on the chamber's east, contained a staircase leading down to the chapel. Additionally, the great chamber seems to have had a doorway providing access to the walkway in the hall's frontispiece and from there to the Cecils’ lodgings in the north range.

On the east, the state apartment continued with a withdrawing chamber, known in Elizabethan times as the ‘vyne’ or ‘vine chamber’ – presumably on account of its decoration. During the house's time as a royal palace, it came to be known as the privy chamber.Footnote 76 Positioned above the chapel, it had a carved chimneypiece with a wainscot overmantel. Beyond, at the centre of the south range, was the queen's bedchamber. Contemporary references make clear that this room was positioned beneath a turret, which gave it external emphasis.Footnote 77 The parliamentary survey records that it was part lined with hangings and part panelled, with a border of wainscot ‘cutt curioslie, and coullered’, with gilded edges. Served by a stool house, the chamber had ‘fair windows’ and a stone chimneypiece with a timber overmantel featuring four pilasters.Footnote 78 The royal arms was added in the early 1600s, though the overmantel may have featured Queen Elizabeth's arms even before this time. Visiting Theobalds in 1599, Roger Wilbraham found ‘in the Qs chamber written over the chymney, Semper Adamas [always firm]’ – probably a mistake for Semper Eadem (always the same), which was Elizabeth I's personal motto.Footnote 79

When it came to the area on the east of the queen's bedchamber, there were two phases of construction. In the first phase – from the completion of the south range in c. 1572 until that of the projecting range in c. 1574 – this area contained a gallery, mentioned in the schedule of accommodation of 1572.Footnote 80 The fact that it was a key part of the original design is implied by the apparent symmetry of the plan of the Middle Court: in the north range, as shall be seen, Lord Burghley's second-floor suite included a gallery in the corresponding position.Footnote 81 Once the gallery had been superseded by the Privy Gallery in 1574 (discussed below), the space beyond the queen's bedchamber was reworked. The schedules of 1577, 1583 and 1591 show that this area included two chambers.Footnote 82 These were allocated to the queen's gentlewomen during royal visits, and functioned as closets – one large and heated, the other small and utilitarian. From this part of the suite a door led towards the roof walk over the Green Gallery.Footnote 83 Seemingly in this area, too, was the ‘Queenes pages roome’, which was connected to the back staircase.Footnote 84

By 1650, this inner accommodation appears to have been expanded, for the survey also includes the ‘Queen's Coffer Chamber’, which featured a wainscot overmantel ‘well painted and gilded’.Footnote 85 This was probably positioned at the east end of the range, with a bay window looking east (see Fig. 4). A sizeable room in this position is not mentioned in any of the Elizabethan schedules of accommodation – a notable omission – and so it is probable that this area was originally occupied by the north end of the Privy Gallery.Footnote 86 It could have been partly separated off as a lobby, like those later included at each end of the first-floor long gallery at Hatfield House. At Theobalds, the area must have been subsequently divided off to form a completely separate chamber, perhaps in c. 1605–06.

Additionally, the inner area of the state apartment was associated with rooms in the towers (see Fig. 5). The queen's back staircase led to the leads of the south range and the lodging in the tower at the south-east of the court, which had a ‘faire large window looking eastward’.Footnote 87 The staircase seems also to have formed the principal access to the room in the tower above the queen's bedchamber, a position of importance.Footnote 88

In c. 1572–74, Theobalds's state apartment was extended by the addition of a long gallery. The provision of this space clearly constituted the raison d’être for the construction of the three-storeyed projecting range (see Fig. 10), and it seems that this feature of the Theobalds layout proved immensely influential in reinforcing a fashion for the building of spacious long galleries in association with state apartments. Earlier country houses that included state apartments with long galleries were Hampton Court (c. 1514–16) and Ingatestone Hall in Essex (c. 1540–45), but they were by no means common in the first half of the sixteenth century. That situation changed after the mid-1570s: almost all later Elizabethan and Jacobean country houses of significant size and pretension featured long galleries, including Holdenby, Kirby Hall (c. 1575–84) and Wollaton Hall.Footnote 89 The natural conclusion is that Cecil's work at Theobalds was a catalyst, being innovative in both this and other respects.

Initially, Burghley had provided a relatively modest gallery in the south range. Now, he made up for any error of judgement by building a grand gallery, which was known as the Queen's Gallery by 1583 and retained this name until 1650,Footnote 90 although it was also known as the Privy Gallery.Footnote 91 According to the parliamentary survey, the room was 14 ft (4.3 m) wide and 109 ft (33.2 m) long – the same length as the Green Gallery.Footnote 92 It had an ‘arch seelinge’ – seemingly a barrel-vault, like that in the long gallery at Chastleton House in Oxfordshire (1607–12; Fig. 15).Footnote 93 The room's walls were panelled and ‘well painted’, the chimneypiece was of freestone, while (judging by the surviving elevation drawing) there were bay windows on the room's west side, overlooking the Great Garden. There may also have been bay windows on the room's east, in the upper levels of the two staircase turrets. Opening off the gallery was a stool house, while the room's northern end contained a door leading to the lead walk over the Green Gallery.Footnote 94

Fig. 15. The interior of the barrel-vaulted long gallery at Chastleton House, Oxfordshire, built in 1607–12 (© National Trust Images/Nadia Mackenzie). It may have been influenced by the barrel-vaulted Privy Gallery at Theobalds, built in the 1570s

Other descriptions of the Privy Gallery appear to survive, a fact that has not been acknowledged before. Frederic Gerschow, a visitor of 1602, was probably referring to this room when he described a gallery containing ‘the coats-of-arms of all the noble families of England, 20 in number, also all the viscounts and barons, about 42, the labores of Herculis, and the game called billiards, on a long cloth-covered table’.Footnote 95 Another to refer to the Privy Gallery was Johann Albrecht de Mandelslo, a visitor of 1640. He recorded that the gallery contained portraits ‘en grand’ of Queen Elizabeth, several other queens of England, and a group of Protestant leaders – John Frederick (1503–54), Elector of Saxony, Admiral Chatillon (1519–72), Cardinal Chatillon (1517–71), and their brother Francois de Coligny d'Andelot (1521–69) – as well as portraits of the Turkish emperors and ‘les travaux d'Hercule en sept tableaux’.Footnote 96

In a tower at the south end of the Privy Gallery was a lodging clearly intended to be used by someone associated with the occupant of the state apartment.Footnote 97 Given this intimate connection, it is fascinating to find that the lodging was used successively by Queen Elizabeth's two most notable favourites – firstly, in 1577 and 1583, by Robert Dudley (1532/3–88), first Earl of Leicester, and in 1591 by Leicester's godson, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex.Footnote 98 According to schedules of accommodation, the lodging comprised a chamber with two pallet chambers, though the parliamentary survey seems to refer to three chambers, with three associated lobbies. One of these chambers featured a freestone chimneypiece, carved and gilded, with a timber overmantel ‘painted with pictures and covered green and gilt with gold’.Footnote 99 Another was referred to as the ‘corner chamber’ and had windows looking south and west into the Great Garden, with a ‘fair chimneypiece of stone, with a rich painting over it’. This was probably the principal room of the queen's favourites, for in 1591 it is clear that Essex was accommodated on the gallery's ‘garden side’.Footnote 100 Accounts of 1578 record the painting of ‘my Lo of Lec Armes over the chymne’,Footnote 101 and this is likely to refer to the ‘corner chamber’; the painting probably served to commemorate the earl's stay of May 1577. A staircase here led to the ground-floor Still House Chamber (used by Leicester's servants during his stays), the loggia and the garden, as well as to the first-floor lodgings; in 1591, the southernmost of these provided a dining room for Essex, thereby expanding his suite.Footnote 102

Another gallery, the long gallery above the great hall, was apparently accessible from the queen's rooms, although it did not form part of the state or any other apartment (see Fig. 5). This is likely to have been created in the phase of work of c. 1567–70, and seems to have represented a change from the initial design. The gallery occupied a slightly higher level than that of the state apartment, although it was probably not as high as the rooms in the tower at the south end of the hall range (see Fig. 6). This lodging in the ‘great tower’ or ‘Earles Towre’ seems to have been traditionally allocated to the Lord Chamberlain, and may be identified with the ‘King's Secretary's Chamber’, plus closet and inner chamber, referred to in the survey of 1650.Footnote 103

Probably, both gallery and tower lodging were accessed via the newel staircase which rose between the queen's great and withdrawing chambers, though the gallery was seemingly also accessible from the north staircase.Footnote 104 Almost certainly, it was this gallery that Baron Waldstein referred to in 1600 when writing that ‘Upon the roof of the house there is a splendid gallery from which you can see the Tower of London’.Footnote 105 The room contained ‘a closett vawted with stone for evidences’.Footnote 106 This was an evidence house, a secure place for the storage of documents and other valuables, and it may have been located in the upper part of the stone frontispiece on the gallery's east side. Beyond this, nothing is known about the gallery's arrangement and decoration: by 1650, it had been subdivided into ‘12 verrie small rooms’.Footnote 107 Nor is anything known about the rooms at the south and north ends of the gallery, positioned above the great chamber and Lady Burghley's lodgings respectively. It is likely, however, that those on the south comprised the chamber, pallet chamber and two ‘Chaplannes chambers’ listed in the survey, while those on the north may have included the lodging of the Lord Chamberlain;Footnote 108 the latter seems to have been used earlier (in 1572) by Sir Christopher Hatton (see below).

As well as offering fine views, the gallery above the hall would have provided a route of passage between the state apartment and the lodgings of Lord and Lady Burghley. These were at second-floor level in the north range, running parallel with the queen's rooms (see Fig. 4). The composition of Lord Burghley's lodging can be set out with a fair degree of confidence. At the centre of the north range was his bedchamber, with an associated pallet chamber. Like the queen's bedchamber, Burghley's bedchamber was topped by a turret containing a room, this serving as Burghley's evidence house.Footnote 109 To the east of his bedchamber was a room, listed but unallocated in the schedules of accommodation, which may have served as a withdrawing chamber.

Beyond were the ‘suitor's gallery’ and an inner room, shaped ‘lyke a squyer’.Footnote 110 As with Burghley's bedchamber, his gallery – no doubt named after the crowd which followed him wherever he went – found its parallel in the state apartment on the south, at least as planned before c. 1574.Footnote 111 In 1577 and 1583, the Suitor's Gallery and square room were used for ‘the Lord Treasurer's hall’ or ‘table’ – that is, they functioned as Burghley's great chamber, while his own great chamber in the south range was used by the queen.Footnote 112 During the royal visit of 1591, the square room served ‘for the council chamber’.Footnote 113 Its remote location must have been seen as an advantage, and the room had direct access to the roof walk over the Green Gallery. In addition, the schedules of accommodation for 1591 make clear that Lord Burghley's suite included a ‘book chamber’ or library which seems to have been positioned at the west end of the range.Footnote 114

Next to the north staircase were the rooms of Mildred Cecil (1526–89), Lady Burghley: ‘two lodgings’, ‘terninge Southward towards the hall’.Footnote 115 These placed the lady of the house at the heart of its daily working, with ready access to service rooms, rooms of reception and entertainment, and the first-floor lodgings where the Cecils’ relatives were accommodated. Also associated with Lady Burghley's suite was the ‘towre lodging chamb’ at the north end of the hall range, close to the rooftop long gallery (see Fig. 5); during the royal visit of 1572, this was used by Sir Christopher Hatton.Footnote 116 Since this constitutes the only surviving reference to the lodging (and the north-west tower) in the Elizabethan period, it is likely to have served a private, family use during royal visits. Possibly, it was the lodging of the Cecils’ eldest son, Thomas (1542–1623), or – before the completion of the Conduit Court – of Robert Cecil.

THE CONDUIT COURT

The accommodation of Theobalds was considerably expanded and upgraded in c. 1572–85 by the reworking of the west courtyard, variously known as the Conduit, Fountain, Inner or Third Court. This was 86 ft (26.2 m) square, with blue-slate-covered towers at its four corners, each of which carried four turrets and housed four chambers (see Fig. 7).Footnote 117 The existing hall range formed the courtyard's east side, and there were new – or heavily remodelled – blocks on the other three sides. The range on the north was a single storey in height, with a flat roof. This allowed for a lead walk, joining the hall and west ranges, and gave the state rooms on the south an open prospect northwards. The ranges on the south and west of the Conduit Court were of two storeys with flat roofs. The height of the first floor seems to have been greater than that of the Middle Court, with the rooms at this storey probably being almost level with the latter's second-floor rooms (see Fig. 4). The west side of the hall block was fronted with a loggia of seven arches, with a lead walk above.

Accessed from the north staircase, the walk on top of the hall range formed the beginning of a circuit, continuing with the flat roofs of the Conduit Court's south and west ranges (see Fig. 6).Footnote 118 The result must have provided extraordinary views, and it was probably this area that was described by Baron Waldstein as ‘an Astronomers’ Walk on the roof-top’.Footnote 119 The leads and walkways also had a different role, providing flexible arrangements for the use and access of the house. These external routes meant, for instance, that it was possible to move from the new state apartment to the family rooms without the need to traverse the great hall.Footnote 120

At the centre of the Conduit Court stood a fountain, which gave the new court its name. This was made of black and white marble, and featured figures of Venus and Cupid, two ‘greate stone boles’ for water, and a ‘figure of an old man’ on the top.Footnote 121 The use of black and white marble was carried into the interiors of the new state rooms, and must have made a very striking impression.

Ground Floor

As Thorpe's plan of c. 1606 shows (see Fig. 1), the north range was dominated by a single room – the north parlour, which was, by 1650, in use as the royal Council Chamber.Footnote 122 The parliamentary survey provides the only known detailed record of this ‘very faire Roome’, which had a bay window overlooking the courtyard. The parlour was floored with wood and ‘pavements of Divers Coulleurs’, while its walls were lined with wainscot. It had a carved freestone chimneypiece and, like the new great chamber on the south, had windows featuring coats of arms.Footnote 123 At the parlour's east end was a small inner or withdrawing chamber, which was later used ‘for the Clarkes of the privie Councell to wright in’.Footnote 124 On the parlour's west was another withdrawing room, with an adjacent staircase; this provided access to the leads, the Great Gallery and the lodgings in the north-west tower.

The north parlour served as a grand space for daily dining and entertainment for the Cecil family.Footnote 125 In particular, though, it must have been used by Robert Cecil, for whom the estate of Theobalds had apparently been acquired. It seems that Theobalds was formally settled on Robert by an indenture of 16 June 1587, and it has been said that he took possession of the house around spring 1589, Lord Burghley moving to Robert's house of Pymmes in nearby Edmonton.Footnote 126 Certainly, increasingly prominent in the political and court arenas, Robert would have required lodgings of status. Knighted (at Theobalds) in 1591 and elevated to the Privy Council the same year, he was then appointed Secretary of State in 1596 and remained a significant figure under James I – he was created first Earl of Salisbury in 1605 and appointed Lord Treasurer in 1608. It is known that Theobalds contained a lodging allocated to the Earl of Salisbury by 1607–09 and, although its location is not mentioned, it is likely that this refers to the rooms on the ground floor of the Conduit Court's west range, which were named ‘ye Lord of Salisburies Lodginges’ in the survey of 1650 (see Fig. 2).Footnote 127

Thus, the north parlour can be seen as the first room in Robert Cecil's great apartment, and there seems to have been a similar apartment on the south of the courtyard, perhaps intended for Robert's future wife – he married Elizabeth Brooke (1562–97) on 31 August 1589 – or a high-status visitor. While the suite on the south is likely to have continued into the south-west tower, that on the north was larger, extending into the western range, probably leaving the rooms in the north-west tower as a self-contained lodging. By 1650, the chambers in the west range included ‘my Lord of Salisbury's Dining Room’, an adjacent ‘Retiring Room’, another room adjoining a stool house, and ‘Lord Salisbury's bedchamber’.Footnote 128

The rooms in the tower at the north-west corner of the Conduit Court probably represent the ‘double lodging’ in which John Wolley (d. 1596), Secretary to Queen Elizabeth, was accommodated in 1591.Footnote 129 It is notable, given his accommodation in this part of the house, that Wolley was a close colleague of Robert Cecil. Other friends and allies of Robert Cecil to be accommodated in this area during the royal visit of 1591 were John Stanhope (c. 1540–1621), Master of the Posts, and Sir George Carew (1555–1629), Master of the Ordnance in Ireland.Footnote 130

At the south-west corner of the Conduit Court, under the state bedchamber, were rooms occupied during the royal visit of 1591 by William Brooke (1527–97), tenth Baron Cobham.Footnote 131 He was perhaps Lord Burghley's oldest friend but – more relevant for his accommodation in this area – he was also, from 1589, Robert Cecil's father-in-law. This lodging comprised four rooms and was adjacent to the terrace on the south side of the house. It may have been the same lodging of four rooms named in the parliamentary survey as the chambers of the ‘Marquis of Hambleton’, probably a reference to James (1606–49), third Marquess of Hamilton, a favourite of James I and Charles I. According to the survey, the lodging included a bedchamber, with a door leading to the Great Garden, and a dining room, looking north.Footnote 132 The survey shows that there were three rooms on the east of this lodging, allocated by 1650 to Henry Rich (1590–1649), first Earl of Holland, one of James I's intimates.Footnote 133 Thorpe's ground plan of c. 1606 (see Fig. 1) does not show a sufficient number of rooms in this area, so it is probable that the large chamber which stood beneath the great chamber was subdivided at some point after 1607.

On the outer side of the south range, facing the Great Garden, there was a loggia. This had seven arches and its walls were ‘painted with the kinges and queenes of England, and the pedigrees of the old lord Burley's and divers other antient families, with paintinges of many castles and battailes’.Footnote 134 The loggia was accessible from beyond the foot of the great staircase, and therefore served to link house and garden. Visitors to describe this loggia were Paul Hentzner, who came to Theobalds in 1598, and Baron Waldstein, who visited two years later and mentioned a ‘gallery’ featuring ‘portraits of the Cecil family, with an account of the notable acts of each under different reigns’.Footnote 135 In 1640, Mandelslo described the loggia as including the arms of Cecil and his wife, ‘who were descended from the ancient Kings of England’; above were statues of several English kings.Footnote 136

Returning to the interior of the house from the loggia, a visitor would have encountered the great staircase. The great stair had been in this position since the completion of the hall range in 1570, providing access to the state apartment on the second floor of the Middle Court. It also had an adjacent flight descending to the basement, where rooms included wine cellars beneath the great parlour and the new south range. With the remodelling of the Conduit Court, the great staircase is likely to have been altered; it is certainly known that work was under way on the glazing of the stair's compartment in 1582.Footnote 137

Lord Burghley's feelings about the need for grandeur in the ascent to state rooms have been recorded, and it is likely that the staircase at Theobalds was impressive and innovative.Footnote 138 In 1650, it was described as a ‘verry faire halfe pace stairecase with carved posts, and with Lyons on the topps excellent well carved’.Footnote 139 It was made up of thirty-two steps and, judging by Thorpe's plan (see Fig. 1), was of open-well construction. Thorpe seems to show a screen dividing the staircase from the lobby; this may have resembled that at Knole in Kent and may, as at that house, have been carried through to the stair's upper part. The survey makes clear that the staircase – named the ‘Kinges Staires’ – had five foot paces or landings, and it must therefore have risen twice round, through two floor levels.Footnote 140 The stair hall bore a plaster ceiling, with ‘gilded pendance hanginge Downe’.Footnote 141 As Summerson noted, this staircase is believed to survive (though altered), having apparently been re-erected at Crews Hill House, Enfield, then at nearby Theobalds Park, and finally, in c. 1933, at Herstmonceux Castle, Sussex, where it remains today (Fig. 16).Footnote 142

Fig. 16. The staircase at Herstmonceux Castle, East Sussex, said to have originally been the great staircase at Theobalds, probably created c. 1570 and altered in the early 1580s (© Crown copyright: Historic England Archive). The stair was apparently moved to Herstmonceux from Enfield in c. 1933

First Floor and Towers

From the 1580s, Theobalds's great staircase led to both the state apartment in the Middle Court and that in the Conduit Court (see Fig. 4). It also provided access to the leaded walk over the loggia on the west of the hall, which led to the north side of the house. Thus, it represented a crucial joining point. The first apartment to be encountered by a visitor would have been the state suite of the Conduit Court. This was made up of six main rooms and, in plan, was L-shaped. The most public room was the great chamber, known as the ‘King's Presence Chamber’ by 1650.Footnote 143 In the sixteenth century, it would have been used – by Burghley and the queen – for dining in state, as well as receptions and entertainments. The interior of the great chamber is well documented, and constituted perhaps the most extraordinary decorative scheme at Theobalds. For Jacob Rathgeb, a visitor of 1592, the room was ‘so ornamental and artistic that its equal is not easily to be met with’; its overall effect was ‘right royal’.Footnote 144

In 1585, Lord Burghley stated that the room had been created after the queen found fault ‘with the smal mesure of her chamber’, almost certainly the great chamber in the Middle Court. He wrote that the new room ‘need not be envied of any for riches in it, more than the shew of old oaks, and such trees with painted leaves and fruit’.Footnote 145 The earliest known description of the room – and a record that has been rarely cited to date – is given in an undated letter written by Charles Cavendish to his mother, Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury. The letter can be confidently ascribed to July 1587, when Queen Elizabeth was staying at Theobalds. Cavendish, who was obviously one of the party, wrote that:

[Burghley's] great chamber I take to be lx foott long xxii brood and xxi hy wherin he hath mad at the nether end a fayre rock wt duckes fesantes wt divers other birdes wch serves for a cubbord, the ould trees be thir still. he … hath in the Rouff a sunne goinge wch truly poynteth the hower and goeth the len[g]t[h] of the chamber, by nyght the moune and through the rouff wch be bordes paynted sky holes mad[e] lyghtes sett ther so the[y] appeare stares.Footnote 146

Much of what Cavendish describes is confirmed by later accounts, including that by Rathgeb, who wrote in 1592:

On each side of the hall [great chamber] are six trees, having the natural bark so artfully joined, with birds’ nests and leaves as well as fruit upon them, all managed in such a manner that you could not distinguish between the natural and these artificial trees.Footnote 147

According to Baron Waldstein, these trees were columns, ‘covered with the bark of trees, so that they do in fact look exactly like oaks and pines’.Footnote 148 This decoration led to the room's Elizabethan title, the Arbour or Arbor – a name mentioned in contemporary documents but not hitherto acknowledged by historians. It was known as such by at least 1585, and in 1591 was clearly referred to by this name as the first room in the queen's state apartment.Footnote 149

Another feature of the great chamber, the ‘fayre rock’ or grotto, was under construction in 1584, and included sparkling quartz ‘priors stones’ from St. Vincent's Rock near Bristol.Footnote 150 The grotto was described by Rathgeb as ‘a very high rock, of all colours, made of real stones, out of which gushes a splendid fountain that falls into a large circular bowl or basin, supported by two savages’.Footnote 151 Waldstein wrote of it as ‘an overhanging rock or crag (here they call it a “grotto”) made of different kinds of semi-transparent stone, and roofed over with pieces of coral, crystal, and all kinds of metallic ore’. He added that it was ‘thatched with green grass, and inside can be seen a man and a woman dressed like wild men of the woods, and a number of animals creeping through the bushes’.Footnote 152 At its base stood a bronze centaur. Clearly, the grotto was largely decorative, although the fountain may have been partly intended for the washing of hands after meals (a fountain also featured in the great chamber of the Middle Court).

Such an elaborate and curious ‘device’ must have delighted Elizabeth and her courtiers, but the great chamber's ceiling was even more extraordinary. In 1592, Rathgeb wrote of this in the following terms:

The ceiling or upper floor is very artistically constructed: it contains the twelve signs of the zodiac, so that at night you can see distinctly the stars proper to each; on the same stage the sun performs its course, which is without doubt contrived by some concealed ingenious mechanism.Footnote 153

Cavendish's description (quoted above) gives further clues as to how this effect was achieved. It would seem that the ceiling was made of boards, painted like the sky and pierced with holes. Above these holes lights were set which, after dark, gave the impression of stars. The movement of the sun and moon – along the length of the chamber, around 60 ft (18.3 m) – must have been incredible indeed. No more is known about this ceiling, or who carried out the work. It seems certain, however, that its mechanism was set within a space above the boards, and that the great chamber did not, therefore, carry through the full height of the range.

Other features of the great chamber were a ‘cloth of estatt mad of thin horne of divers colers’ and, according to Baron Waldstein, two chimneypieces, one of alabaster and another ‘in black and white marble’.Footnote 154 The parliamentary survey refers only to the latter, which had ‘4 pilasters of the same stone wth the Queenes armes in the midst richlie gilt wth two Brasse Colomes of the figures of Vulcan & Venus standinge before ye jammes of the chimney’.Footnote 155 It was being made in 1581–82.Footnote 156 The great chamber's windows included bays opening both north and south. According to the survey, these were set with ‘severall Coates of Armes’, which a visitor remarked belonged to ‘the principal potentates of the world’.Footnote 157 Following contemporary conventions in planning, it is likely that the west wall of the great chamber fell just beyond these bay windows.

According to the 1591 schedule of accommodation, the ‘Queen's Arbour’ was followed by another state room: the privy chamber, a name the room retained during Theobalds's years as a royal palace.Footnote 158 In 1650, the privy chamber was part wainscotted and part fitted for hangings, and contained a chimneypiece of black and white marble, with carved figures on each side and a ‘faire frontispiece’ of the same stone, carved and set above.Footnote 159

By 1650, the privy chamber was followed by the ‘withdrawinge Chamber’, which had clearly existed for some time.Footnote 160 Part of the room was fitted for hangings and the rest ‘verrie fairely wainscotted’.Footnote 161 This room is not mentioned in the 1591 schedule, and seems a strange omission given its importance and the comparative detail of the document. It is therefore possible that the withdrawing chamber was created by Sir Robert Cecil, as part of the alterations he undertook during the early seventeenth century. The creation of the room would have involved curtailing the earlier privy chamber and, possibly, state bedchamber, and the insertion of a wall with a chimneystack (see Fig. 4). The chimneypiece of the withdrawing chamber may be seen to offer support of this theory: in being made of ‘richlie carved and gilded’ freestone, with a timber overmantel, it broke the sequence of the others in the state apartment, which were of black and white marble.Footnote 162

Dominating the south-west tower of Theobalds was the state bedchamber. This featured a chimneypiece of black and white marble, with three pilasters and ‘carved works, wrought and sett above the same’.Footnote 163 A ‘great square window’ overlooked the Great Garden, and there were ‘twooe lesser windowes’, looking west.Footnote 164 The walls were part panelled ‘with special worke’, and the plastered ceiling was painted and gilded – it seems to have featured 120 ‘knobbes’.Footnote 165 The 1591 schedule refers to a single pallet chamber (closet) in association with this bedchamber.Footnote 166 This was presumably the room with a stone chimneypiece ‘where the pages of the Backstaires weighted’, and the survey also mentions an adjacent stool house.Footnote 167 The back staircase – the lower part of which is shown in Thorpe's plan (see Fig. 1) – was referred to in the survey as the ‘Gallerie Staires’.Footnote 168 It led to the leaded walk and rooms in the south-west tower, as well as to the ground-floor lodgings and courtyard.

On the north of the state bedchamber and inner rooms was a long gallery. Known as the Great Gallery by at least 1587, and ascribed to the queen in 1591,Footnote 169 the gallery was entered via a ‘faire wainscott portall, richlie carved’ and measured 123 ft (37.5 m) long and 21 ft (6.4) wide, making it the largest of Theobalds's long galleries.Footnote 170 It had a plaster ceiling, featuring ‘divers pendants roses and flower deluces, painted and guilded with gold’.Footnote 171 It was almost certainly this ceiling that Jacob Rathgeb sketched in 1592 (Fig. 17).Footnote 172 The gallery had three square lobbies in window bays, two of which would have been on the west side, overlooking the Maze Garden, with the other on the east. There were also other windows on both sides, ‘makinge the roome verrie delightfull’, as well as windows at the gallery's north end.Footnote 173

Fig. 17. Drawing by Jacob Rathgeb, secretary to the Duke of Wirtemberg, of a ceiling at Theobalds, 1592, as published in W.B. Rye's England as Seen by Foreigners in the Days of Elizabeth and James the First (1865). It is likely that it depicts the plaster ceiling in the Great Gallery, built in the 1580s

A door at the north-west corner of the gallery opened on to a stone staircase of thirty-two steps descending to the Maze Garden, while a door on the room's north-east led to the lead walk over the single-storey north range (see Fig. 4). Also in this area of the house was another staircase, ‘on ye North corner of the buildinge over ye greate Gallerie’.Footnote 174 This, shown in Thorpe's ground plan on the west of the north parlour, led to the leads and tower lodgings.

Adjoining the gallery, seemingly close to the stone staircase, was a wainscotted ‘Lodginge Roome’ with a chimneypiece.Footnote 175 This is probably the room referred to by Mandelslo, a visitor of 1640, as ‘a little cabinet panelled and painted’ at the end of the gallery.Footnote 176 It may also be the ‘great passage room’ mentioned in the Royal Works accounts of 1620–21.Footnote 177 It is unclear what function this room was intended to have, but it was probably more a withdrawing chamber than a lodging, since it does not appear to have been associated with a closet.

It is possible that this area of Theobalds was depicted in a contemporary painting. The work dates from c. 1630–35 and shows an interior, with the figures of King Charles I, Queen Henrietta Maria, William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke, his brother Philip Herbert, later fourth Earl of Pembroke – the brothers served successively as Lord Chamberlain – and the court dwarf Jeffrey Hudson (Fig. 18). There are also two painted copies of the work, as well as an engraving of c. 1800. The original painting and one of the copies are associated by tradition with Theobalds, the other copy being said to represent the palace of Whitehall.Footnote 178

Fig. 18. Interior view of King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria with William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke, and his brother Philip Herbert, later fourth Earl of Pembroke, successive Lord Chamberlains; on the left is the court dwarf Jeffrey Hudson (© Crown copyright: UK Government Art Collection). The painting has been ascribed to artists including Hendrick van Steenwyck and dates from c. 1630–35. The background is said by tradition to be Theobalds, and may relate to the Great Gallery

The link with Theobalds has, before now, not been interrogated, it being believed that there was insufficient information about the house's plan to reach a conclusion.Footnote 179 The present study shows that the view – if it is indeed of Theobalds – can only be of the Great Gallery, which would be appropriate as this room formed part of King Charles's state apartment and was an area he is known to have made use of.Footnote 180 Although the differences with what is known about the house are numerous, there are some elements that tie in. For instance, the staircase on the right could be that which led to the Maze Garden. It is interesting, too, that an inner room is shown at the gallery's end, in the foreground. At the very least, this provides a sense of how Theobalds's ‘cabinet’ or ‘Lodginge Roome’ may have been arranged. Moreover, if the view is of Theobalds – or inspired by it – then the painting has significance as being the only fully illustrative interior depiction of the house known to exist.

In terms of its decoration, the Great Gallery featured a chimneypiece matching the others in the state apartment. Installed shortly before the queen's visit of 1591, it was of black and white marble, with eight columns and an overmantel bearing ‘Divers carved and painted figures of horse and men’.Footnote 181 Justus Zinzerling, a visitor of c. 1610, implies that it was inscribed in French with the history of ‘Joannes de Sitschitz’ and ‘Guil. Fanacham’, a moment of heraldic significance to the Cecil family.Footnote 182 The gallery's walls were panelled, and above were paintings of various cities. These were complete by 1592, for in that year Rathgeb recorded seeing ‘very artistic paintings and correct landscapes of all the most important and remarkable towns in Christendom’.Footnote 183 In 1602, Frederic Gerschow added that these depicted ‘the most splendid cities in the world and their garments and fashions’.Footnote 184

Hung around the gallery's walls were, according to Baron Waldstein, portraits of ‘the Roman Emperors from Julius Caesar to Domitian’, as well as some of the knights-commanders of the Golden Fleece, the English kings Richard III, Henry IV, Edward IV, Henry V, VI and VII, and – on the opposite wall to the kings – portraits of six noblemen who were prominent on the Continent: Don Juan of Austria (1547–78); Alessandro Farnese (1545–92), Duke of Parma; Lamoral (1522–68), Count of Egmont; the Admiral of France (1519–72); Louis (1530–69), Prince de Condé; and the Duke of Saxony (probably John Frederick [1503–54], Elector of Saxony).Footnote 185 As James Sutton has noted, there seems to have been an emphasis on the number twelve in this decorative scheme – six portraits of English kings, six of men prominent in continental Europe, twelve Roman emperors and perhaps twelve knights of the Golden Fleece. Sutton's suggestion that there may have been twelve city views in the friezes on each side of the room seems sensible.Footnote 186 The gallery is known to have contained busts of the twelve Caesars and a ‘terrestrial globe’ which was twelve spans (9 ft/2.7 m) in circumference.Footnote 187 It is no wonder that overseas visitors commented upon this decorative scheme, and it is likely that Lord Burghley intended the room to have this effect, encouraging pride among visitors from abroad, educating his countrymen about European affairs, and emphasising the breadth of his own knowledge and connections.

Like the Privy Gallery of the Middle Court, the Great Gallery at Theobalds imitated royal long galleries by being placed at the inner end of the state apartment and leading nowhere. It formed the culmination of the new suite, and was clearly a magnificent room, used as the setting for grand entertainments.Footnote 188 Nevertheless, like its royal equivalents, it would have been intended as a semi-private space, reflecting its proximity to the state bedchamber and associated inner rooms. The irony is that, although Queen Elizabeth clearly made use of the state rooms in the Conduit Court, she preferred to remain in her older, more limited and secluded accommodation in the Middle Court. In terms of its full usage, the Conduit Court was to experience its glory at another, later period.

THEOBALDS UNDER SIR ROBERT CECIL, EARL OF SALISBURY (1598–1607), AND JAMES I AND CHARLES I (1607–49)

Few substantial changes appear to have been made to the plan of Theobalds between the completion of the Conduit Court and the death of Lord Burghley in 1598. However, alterations were certainly made by Sir Robert Cecil, and these seem to have been more extensive than has previously been recognised. Detailed records of the changes do not survive, though references to them provide useful evidence. Work was in train in the gardens and apparently on the house by 1602.Footnote 189 A visitor of that year commented that of Theobalds's five courts, ‘the last was not quite finished’.Footnote 190

Rebuilding was still under way, or was re-initiated, around March 1605. On 2 April that year, Humphrey Flynt, the keeper of Theobalds Park, wrote to Cecil that ‘Your works appointed to be done about the house be in hand and there shall be as much speed made of them as possible’.Footnote 191 On 22 May 1605, Sir Fulke Greville wrote to Cecil following a visit to Theobalds:

In your buildings I have some little quarrel to the windows of your new old gallery. I mean those next to the leaded terrace …. The alterations in your lodgings is passing good and will amend them both for sight and use exceedingly; yet if the old windows even in them had been carried up a little higher the commodity would thoroughly have recompensed for any little eyesore without, if any such must have grown by it, which I doubt of.Footnote 192

Greville's reference to the ‘new old gallery’, which lay adjacent to a leaded walk, indicates one of two rooms: the great chamber or the Great Gallery of the Conduit Court (see Fig. 4). As to the lodgings, this reference must include the state apartment of the Conduit Court, and almost certainly that of the Middle Court also. Confirmation that changes were under way in these areas, and in other parts of the house, is given by bills for painters’ work undertaken in 1605 and 1606.Footnote 193

As has been recognised,Footnote 194 Robert Cecil's programme of work included the interior of the west great chamber, which, in August 1602, Roger Houghton, Cecil's head of household at Theobalds, referred to as the ‘great chamber gallery’.Footnote 195 The extravagant decoration created by Lord Burghley was apparently still in place in 1600, when Baron Waldstein visited and described the room, although he made no mention of the mechanical ceiling. Two years later, in June 1602, the trees in the room's interior seem to have been in situ.Footnote 196