Healthcare workers are often reluctant to seek mental healthcare, with stigma regarding treatment being a profound obstacle.Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs1 Stigma includes perceiving treatment-seeking as a weakness, anticipating negative attitudes of colleagues and supervisors, and fearing discrimination in career advancement.Reference Center, Davis, Detre, Ford, Hansbrough and Hendin2 Stigma discourages treatment-seeking and has substantial consequences due to untreated mental health problems.Reference Taylor and Blackford3 Beyond increased risk of depression, suicide and other psychiatric problems, overstressed healthcare workers may report lower motivation, lose productivity and provide lower quality of care.Reference Schwenk, Gorenflo and Leja4 Therefore, early detection and monitoring of healthcare workers’ mental health difficulties are crucial.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed healthcare workers on the front line, exposing them to enormous stress and greater risk for anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Reference Serrano-Ripoll, Meneses-Echavez, Ricci-Cabello, Fraile-Navarro, Fiol-deRoque and Pastor-Moreno5 Healthcare workers already faced high risk for negative effects of chronic stress before the pandemic,Reference Brooks, Chalder and Gerada6 risks now intensified by anxiety and fear. They grieve for patients who have died and feel guilt for not being able to save them. Healthcare workers fear getting sick themselves and experience self-blame for abandoning their families.Reference Taylor and Blackford3 Recent studies have shown increased rates of depression and anxiety symptoms among healthcare workers following the COVID-19 outbreak.Reference Pappa, Ntella, Giannakas, Giannakoulis, Papoutsi and Katsaounou7 At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no sign of ending and many healthcare workers are struggling, feel depleted and need help. Thus, interventions to increase treatment-seeking intentions among healthcare workers are essential.

Research suggests that interventions based on social contact, which involve direct contact with individuals of the stigmatised group, are the most effective way to reduce stigma towards treatment and increase treatment-seeking intentions.Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, vans-Lacko, Doherty and Rose8 People who meet and interact with individuals with mental disorders are likely to lessen their prejudice and discrimination. The mechanism of social-contact interventions is straightforward: an empowered presenter from the stigmatised group describes attaining their goals, preferably in a manner tailored to the viewers’ characteristics to enhance audience identification and emotional engagement.Reference Corrigan, Vega, Larson, Michaels, McClintock and Krzyzanowski9–Reference Amsalem, Yang, Jankowski, Lieff, Markowitz and Dixon11 Studies have shown that video and in-person interventions have similar efficacy in improving attitudes towards mental illness.Reference Janoušková, Tušková, Weissová, Trančík, Pasz and Evans-Lacko12,Reference Koike, Yamaguchi, Ojio, Ohta, Shimada and Watanabe13 Video-based interventions have benefits in cost, resource use, implementation and dissemination. Importantly, no study to date has examined the efficacy of social contact-based interventions in changing treatment-seeking attitudes among healthcare workers.

To address these gaps, we designed a randomised controlled study to test the efficacy of a brief video-based intervention for increasing treatment-seeking intentions among healthcare workers, who were assessed for current levels of clinical symptoms (trial registration: NCT04497415). Healthcare workers were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a brief video-based intervention coupled with a subsequent ‘booster’ video; a single brief video-based intervention; or no intervention (the control condition). We hypothesised that: (a) the video-based interventions would increase treatment-seeking intentions more than the control condition; and (b) the video + booster group would demonstrate greater duration of this effect than the single video group.

Method

Participants and recruitment

Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) is a leading crowdsourcing toolReference Paolacci, Chandler and Ipeirotis14 which has been frequently used in medical and psychology research, including studies assessing treatment satisfaction and brief stigma-reduction interventions.Reference Cunningham, Godinho and Kushnir15 Data acquired on MTurk have been found to be valid across numerous tasks and countries, making the MTurk platform a fast method of acquiring inexpensive and reliable data.Reference Shapiro, Chandler and Mueller16 To enhance participant verification, we recruited participants through TurkPrime, an MTurk-connected internet-based platform designed as a data acquisition platform for social research, which supports tasks common to the social and behavioural sciences.Reference Litman, Robinson and Abberbock17 CloudResearch constantly screens the MTurk population to identify high-quality participants, ensure worker consistency in demographic responses over time, block workers who use tools to hide their location, run checks to identify virtual private network (VPN) usage and create unique anonymous IDs for respondents. We also applied several methods to exclude invalid participants. First, as a validity question we used an open-ended question requiring the participant's age and allowing only a two-digit number as a valid answer. This should have prevented most bots from continuing to the survey itself. Second, we scanned the responses to exclude participants who answered the assessment more than once or completed the survey in less than the minimum expected time. Third, while designing the study, we added a timer before the ‘next’ button appeared, to ensure that participants read instructions (5 s minimum) and watched the video (180 s).

Recruitment took place in September and October of 2020. We required participants to be English-speaking, US-resident healthcare workers 18–80 years old. Healthcare worker was defined as any individual in a health-related occupation: e.g. nurses, physicians and emergency medical technicians. Participants were compensated $6 for study participation. The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board approved the project. Before study entry, participants reviewed an informed consent form. Those who agreed to participate were randomised to complete the study procedures via Qualtrics.com, a secure online data-collection platform.

Trial design

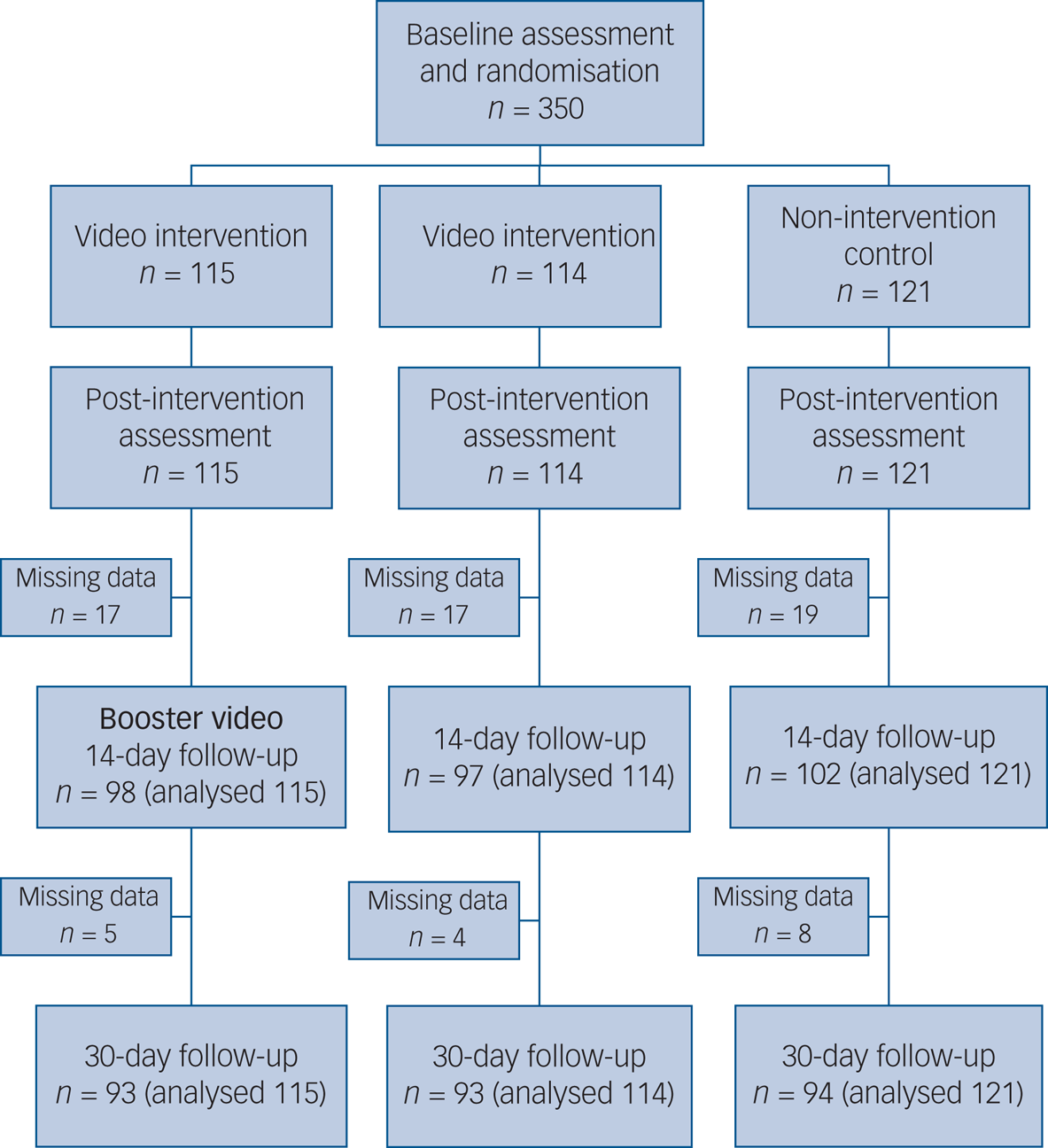

Baseline demographic questionnaires and assessments evaluating clinical symptoms and treatment-seeking intentions were administered before randomising participants to three study groups: a brief video-based intervention at day 1 coupled with a booster video at day 14 (‘video + booster’); a single brief video-based intervention at day 1 (‘video’); or a non-video intervention (‘control’). The two intervention groups (video + booster, video) watched the same short video, and the control group received no intervention (Fig. 1). Immediately following the intervention, we conducted the post-intervention assessment, which included the same measures of treatment-seeking intentions used in the pre-intervention assessment. Fourteen days later, the first group (video + booster) watched the same video again, whereas the other two groups (video and control) had no intervention. The two follow-up assessments were conducted 14 and 30 days following the initial intervention and included the same measures used in the baseline assessment, excluding the demographic questionnaire (see the CONSORT checklist in the supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.54).

Fig. 1 Study profile.

Interventions

The 3 min video derived from a 45 min interview of a 28-year-old intensive care unit female nurse. In a direct and honest manner, she described her difficulty in coping with her life stressors, how she faced her anxieties and depression, her prior false assumptions about treatment and how she overcame them. She described the benefits of social support and psychotherapy and how they helped her to cope with COVID-19 stressors. She concluded with supportive encouragement: ‘Starting treatment was the best thing I did. It changed my life’. The video presented her as a rounded human being and presented her symptoms in the context of this personal human narrative. Thus, the video humanised the suffering via social contact. The booster video was the exact same video.

Outcomes

Treatment-seeking intentions, the primary outcome measure, were measured using three ‘openness to help-seeking’ items from the Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPH-SF).Reference Elhai, Schweinle and Anderson18 The ATSPPH-SF is the most widely used assessment of treatment-seeking attitudes.Reference Picco, Abdin, Chong, Pang, Shafie and Chua19 The items were: ‘I might want to have psychological counselling in the future’, ‘I would want to get psychological help if I were worried or upset for a long period of time’ and ‘A person with an emotional problem is not likely to solve it alone; he or she is more likely to solve it with professional help’. Response options were: 1, ‘disagree’; 2, ‘partially disagree’; 3, ‘partially agree’; and 4, ‘agree’. The total score ranged from 3 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater treatment-seeking intentions. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the ATSPPH was 0.73. Openness to seeking treatment was assessed before and after the intervention and at follow-ups.

The clinical assessments were the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5).

The seven-item GAD-7 assesses generalised anxiety symptoms during the past 2 weeksReference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe20 on a 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’) scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater self-reported anxiety. A total score ≥5 indicates probable anxiety, with high sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%).Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe20 In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

The nine-item PHQ-9, a screening instrument based on the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression,Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams21 assesses depression symptoms during the past 2 weeks. Response options echo those of the GAD-7. The total score ranges from 0 to 27; higher scores indicate greater self-reported depression. A total score ≥10 indicates probable major depression, with 88% sensitivity and 85% specificity.Reference Levis, Benedetti and Thombs22 In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

The PC-PTSD-5, a five-item yes/no self-report questionnaire (1, ‘yes’; 0, ‘no’), is designed to identify probable PTSD. It reflects DSM-5 PTSD diagnostic criteria, with three positive items as the screening threshold.Reference Prins, Bovin, Smolenski, Marx, Kimerling and Jenkins-Guarnieri23 The PC-PTSD-5 has good reliability and showed good operating characteristics compared with clinician interview-based PTSD diagnosis.Reference Ouimette, Wade, Prins and Schohn24 This study adjusted the PC-PTSD-5 to focus on COVID-related events: ‘In the past month, have you felt guilty or unable to stop blaming yourself or others for the COVID-19 related events?’ and ‘Have you felt numb or detached from people, activities or your surroundings?’. Cronbach's alpha was 0.73.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics 26.0 for Mac. We used Pearson's chi-squared (χ2) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare demographic variables and baseline psychopathological characteristics of the three groups. Intervention effects were tested using the generalised estimating equations (GEE) approach,Reference Zeger, Liang and Albert25,Reference Zeger and Liang26 as recommended for randomised trials.Reference Vens and Ziegler27 The GEE approach accounts for correlated repeated-measures analysis and accommodates missing data using estimated marginal means relying on the entire sample. Thus, this analysis strategy includes data from all randomised participants providing at least one data point. To represent within-participant dependencies in the models, we specified an unstructured correlation matrix. We first applied a full factorial model across the four time points (baseline, post-intervention, 14- and 30-day follow-ups) for treatment-seeking intentions and three time points (baseline, 14- and 30-day follow-ups) for clinical symptoms. Group × time interaction terms tested the intervention effect hypothesis of greater treatment-seeking in the two video groups. When between-group differences were found, post hoc tests were used to compare each group pair, including the overall changes from baseline assessment to 30-day follow-up. Effect sizes are reported using Cohen's d when appropriate. All statistical tests were two-sided, using α < 0.05. We considered but rejected a Bonferroni correction for multiple statistical comparisons, given the exploratory nature of this study.

Results

Sample demographic characteristics

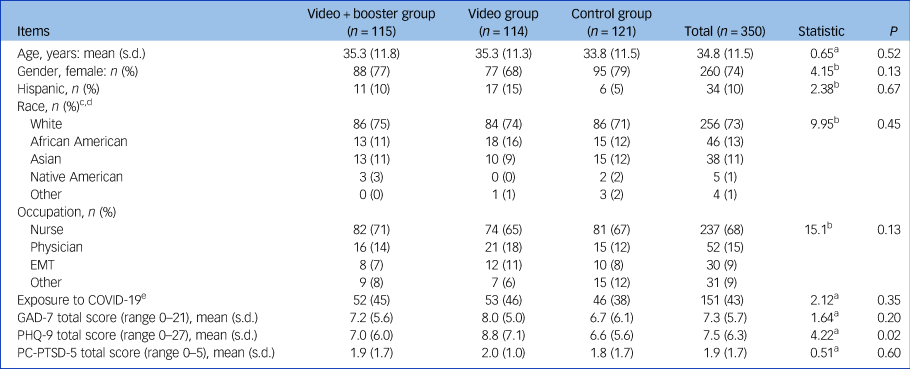

All 350 participants completed pre- and post-intervention assessments, 297 (85%) completed the 14-day follow-up and 280 (80%) completed the 30-day follow-up (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics did not differ between completers and non-completers. The mostly (n = 260; 74%) female sample had a mean age of 34.8 years (s.d. = 11.5; range 18–70). Most participants (n = 256; 73%) self-identified as White; 46 (13%) as African American, 38 (11%) as Asian, 5 (1%) as Native American and 4 (1%) as Other. Thirty-four (10%) reported Hispanic ethnicity (US usage of ‘Hispanic’). Study groups did not significantly differ on gender, age or race/ethnicity (US usage of ‘race/ethnicity’). Baseline GAD-7 and PC-PTSD-5 scores did not significantly differ across study groups. As PHQ-9 scores differed, they were controlled for throughout the analysis (Table 1). The healthcare occupations were nurses (n = 237; 68%), physicians (n = 52; 15%), emergency medical technicians (n = 30; 9%), physiotherapists (n = 12; 3%), pharmacists (n = 8; 2%), hospital administrators (n = 6; 2%), social workers and other therapists (n = 5; 1%).

Table 1 Demographics and psychopathological characteristics of participants by group

EMT, emergency medical technician; GAD-7, seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PC-PTSD-5, Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5.

a. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

b. Pearson's χ2.

c. One person in the video group did not provide this information.

d. US usage of the term 'race'.

e. Denotes participants who tested positive for COVID-19 or had a close friend/family member who tested positive.

Sample clinical characteristics

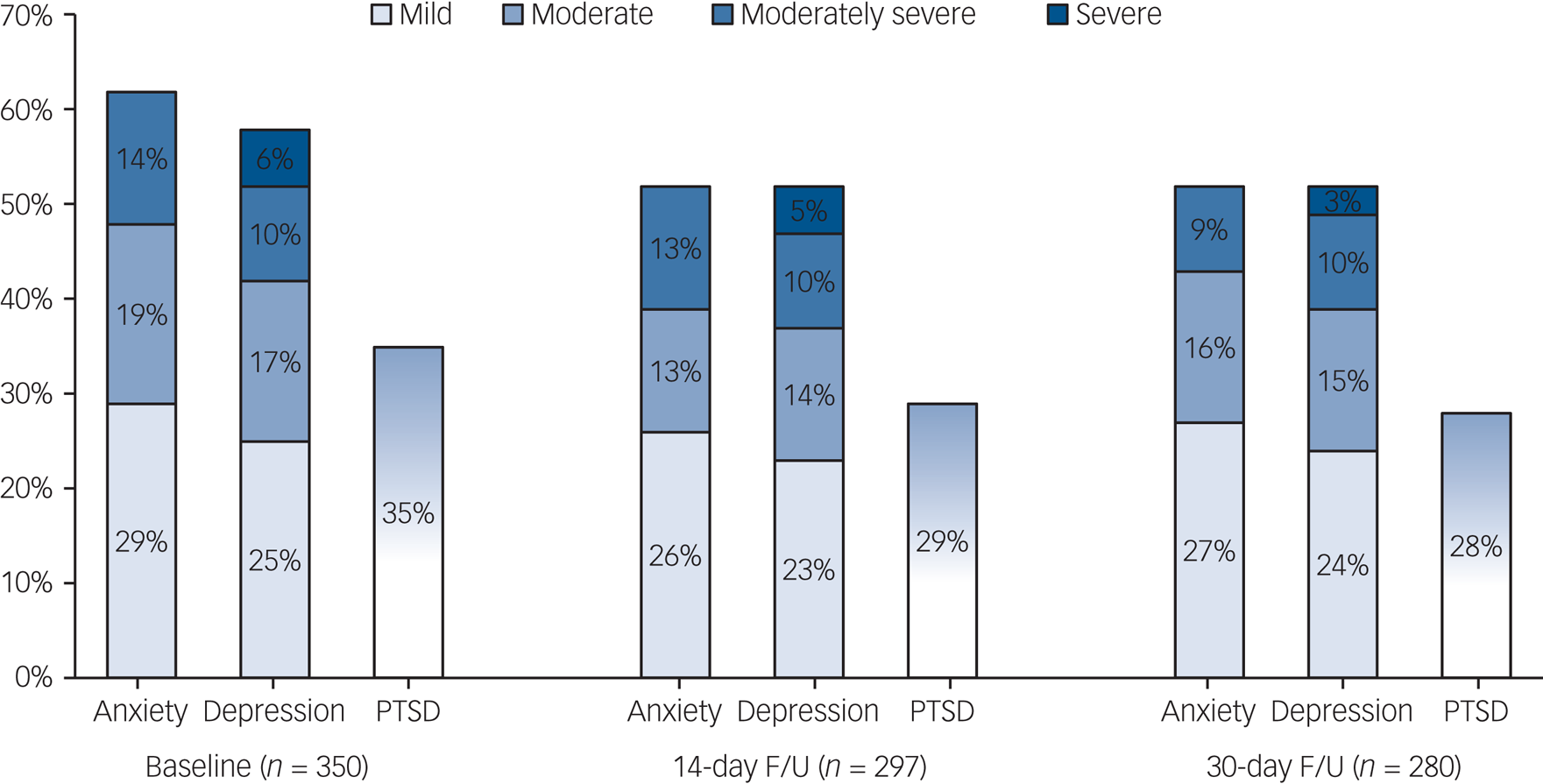

Figure 2 presents psychopathological symptoms over time. Overall, 281 participants (80%) screened positive for anxiety, depression and/or PTSD across time points. Specifically, 215 participants (61%) reached the generalised anxiety disorder threshold (GAD-7 ≥ 5), with 66 (19%) reporting moderate anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) and 49 (14%) severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 15). Two hundred and two participants (58%) reached the depression threshold (PHQ-9 ≥ 5), including 60 (17%) reporting moderate (PHQ-9 ≥ 10), 34 (10%) moderately severe (PHQ-9 ≥ 15) and 20 (6%) severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 20). One hundred and twenty-one participants (35%) reported symptoms suggesting probable PTSD (PC-PTSD-5 ≥ 3). Symptoms remained high, without significant change, at 14- and 30-day follow-ups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Longitudinal presentation of the percentage of positive cases for self-reported anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 5), depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PC-PTSD-5 ≥ 3).

GAD-7, seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PC-PTSD-5, Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; F/U, follow-up.

Intervention effects

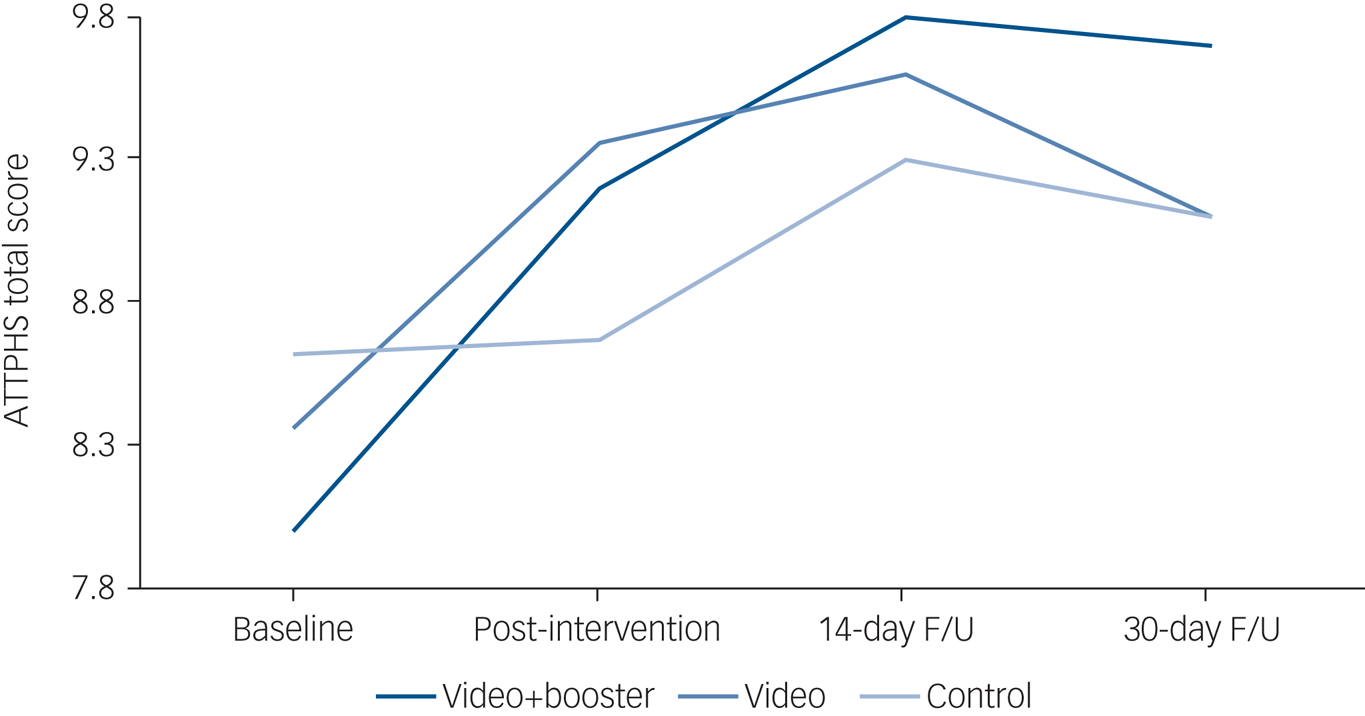

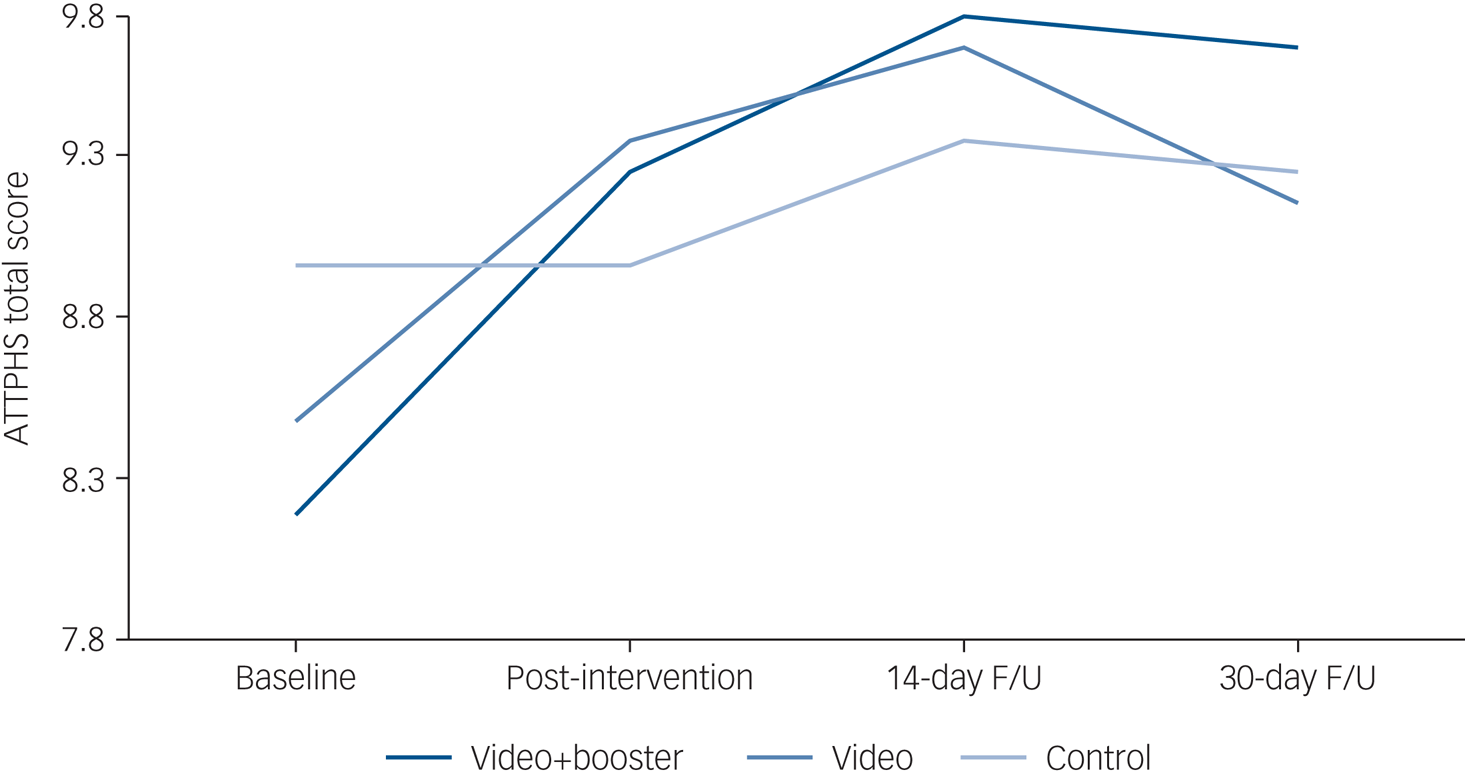

As hypothesised, study group outcomes significantly differed. The brief video yielded higher treatment-seeking intentions in both video groups. Figure 3 presents GEE model results for ATSPPH scores. Baseline scores did not differ across study groups (video + booster group: mean score 7.9, 95% CI 7.3–8.4; video group: mean 8.3, 95% CI 7.9–8.8; control group: mean 8.5, 95% CI 8.1–8.9; one-way ANOVA: F = 1.88, P = 0.16). Analyses showed a group × time interaction (Wald χ2 = 59.4, P < 0.001) such that as time elapsed, participants in the intervention group reported greater treatment-seeking intentions (supplementary Table 1A).

Fig. 3 Comparison between the video + booster (n = 115), video (n = 114) and control (n = 121) groups on the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Help Scale (ATTPHS) over time.

Total scores ranged from 3 to 12, with higher scores indicating higher treatment-seeking intentions (3 = disagree; 6 = partly disagree; 7.5 = neutral; 9 = partly agree; 12 = agree). F/U, follow-up.

Follow-up baseline to post-intervention analyses indicated an expected group × time interaction (Wald χ2 = 61.4, P < 0.001). Only the two video groups showed a significant increase in treatment-seeking intentions from baseline to post-intervention (video + booster group: from 7.9 (95% CI 7.3–8.4) to 9.2 (95% CI 8.7–9.7), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.50; video group: from 8.3 (95% CI 7.9–8.8) to 9.4 (95% CI 9.0–9.7), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.46). Post-intervention to 14-day follow-up analysis showed a group × time interaction (Wald χ2 = 7.2, P = 0.028). Only the video + booster group showed significantly increased treatment-seeking intentions from post-intervention to 14-day follow-up (from 9.2 (95% CI 8.7–9.7) to 9.8 (95% CI 9.3–10.3), P = 0.026, Cohen's d = 0.24). Fourteen-day follow-up to 30-day follow-up revealed only a main effect of time (Wald χ2 = 4.9, P = 0.027). Finally, baseline to 30-day follow-up showed a group × time interaction (Wald χ2 = 54.5, P < 0.001). Only the two video groups showed significantly increased treatment-seeking intentions from baseline to 30-day follow-up (video + booster group: from 7.9 (95% CI 7.3–8.4) to 9.7 (95% CI 9.3–10.1), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.74; video group: from 8.3 (95% CI 7.9–8.8) to 9.1 (95% CI 8.6–9.5), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.33). The video + booster intervention increased treatment-seeking intentions more than the single video (independent t-test 2.54, P = 0.012).

Figure 4 presents the results of a secondary analysis among the 281 (80%) participants who reported psychopathology (anxiety, depression and/or PTSD). Analyses showed a group × time interaction (Wald χ2 = 65.6, P < 0.001) such that as time elapsed, participants in the intervention group reported greater treatment-seeking intentions (supplementary Table 1B). We found a significant increase in treatment-seeking intentions in the video + booster group from baseline (8.2 (95% CI 7.5–8.9)) to post-intervention (9.3 (95% CI 8.8–9.8), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.42) and from post-intervention to 14-day follow-up (9.8 (95% CI 9.4–10.4), P = 0.015, Cohen's d = 0.21). In the video group, we found a significant increase from baseline (8.5 (95% CI 7.6–9.4)) to post-intervention (9.4 (95% CI 8.6–9.9), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.42). Only the two video groups showed significantly increased treatment-seeking intentions from baseline to 30-day follow-up (video + booster group: from 8.2 (95% CI 7.5–8.9) to 9.7 (95% CI 9.3–10.1), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.65; video group: from 8.5 (95% CI 7.6–9.4) to 9.2 (95% CI 8.8–9.7), P < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.30).

Fig. 4 Comparison between video + booster (n = 95), video (n = 94) and control (n = 92) groups on the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Help Scale (ATTPHS) over time among healthcare workers who reported anxiety, depression and/or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Total scores ranged from 3 to 12, with higher scores indicating higher treatment-seeking intentions (3 = disagree; 6 = partly disagree; 7.5 = neutral; 9 = partly agree; 12 = agree). F/U, follow-up.

To better understand the observed intervention effects, we conducted another secondary post hoc analysis. As the video protagonist was a nurse, we examined whether this factor had a greater influence on nurses. Although baseline treatment-seeking scores did not differ between nurses (n = 142) and non-nurses (n = 87) in the video groups (independent t-test 1.1, P = 0.30), nurses showed greater increase in treatment-seeking intentions following the intervention compared with non-nurses (independent t-test 2.0, P = 0.045). Further analysis for 14-day follow-up to 30-day follow-up yielded no effect. We did not find other factors (e.g. gender) that showed such a difference.

Discussion

Our randomised controlled trial examined the efficacy of a brief intervention in increasing treatment-seeking intentions among healthcare workers who were assessed for self-reported anxiety, depression and PTSD. As hypothesised, the brief video-based intervention increased treatment-seeking intentions in the two video-based intervention groups, with longer-term effect noted for the video + booster group. Other interventional studies among healthcare workers during viral epidemics have focused on increasing resilience using educational programmes,Reference Maunder, Lancee, Mae, Vincent, Peladeau and Beduz28,Reference Aiello, Young-Eun Khayeri, Raja, Peladeau, Romano and Leszcz29 reducing stress using exerciseReference Wu and Wei30 or preventing clinical symptoms via multifaceted in-service training.Reference Chen, Chou, Huang, Wang, Liu and Ho31 This is the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of social contact-based intervention in increasing treatment-seeking intentions among healthcare workers.

Overall, both video groups yielded an increase in treatment-seeking intentions from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to 30-day follow-up. However, only the video + booster group yielded an additional increase from post-intervention to 14-day follow-up. We found a similar pattern among participants who screened positive for anxiety, depression and/or PTSD across times points. These findings suggest that repeating the brief video is useful and may further reinforce treatment-seeking intentions. Moreover, comparing baseline with end-point differences between the video + booster and single video groups showed a significant difference in favour of the video + booster group, thus suggesting that adding a booster may increase the duration of the effect. This finding concords with our recent studies comparing a single video-based intervention with a written vignette of the same material, which showed immediately increased treatment-seeking intentions among military veteransReference Amsalem, Lazarov, Markowitz, Gorman, Dixon and Neria32 and a 30-day decrease in stigma towards psychosis in a sample of young adults.Reference Charney, Katz, Southwick and Charney33 Future studies should examine the efficacy of booster videos in sustaining longer-term effects. We suggest that employee assistance programmes (EPAs) consider using these easily disseminated brief videos to encourage employees to seek help if needed.

A secondary, post hoc analysis showed that the video we used had greater influence on nurses, despite a similar level of clinical symptoms at baseline. This difference, found only in the video groups, strengthens our hypothesis that identification with the video presenter (a nurse identifying with a nurse presenter) enhances the social contact effect and yields greater increases in treatment-seeking intentions. We chose a female nurse as the protagonist because we assumed a high rate of nurses and females. However, we did not find a gender difference in our results, most probably because of the low number of males in the sample. Our previous studies demonstrated a similar mechanism for the protagonist's gender and age.Reference Amsalem, Yang, Jankowski, Lieff, Markowitz and Dixon11,Reference Amsalem, Lazarov, Markowitz, Gorman, Dixon and Neria32 Future research should explore whether tailoring interventions to viewer characteristics other than age, gender and race/ethnicity enhances treatment-seeking intentions.

The level of clinical symptoms in our sample of healthcare workers is disturbing. Around 60% of the US healthcare workers we surveyed reported probable anxiety and/or depression and 35% reported probable PTSD: altogether, 281 (80%) reported probable psychopathology. Furthermore, psychopathology remained stable over time. A recent review of the impact on healthcare workers of earlier epidemics showed lower rates of clinical symptoms: anxiety 30%, depression 24% and PTSD 13%.Reference Serrano-Ripoll, Meneses-Echavez, Ricci-Cabello, Fraile-Navarro, Fiol-deRoque and Pastor-Moreno5 The few COVID-19 epidemiological surveys found lower overall rates of anxiety (13–23%) and depression (18–23%) than the present study.Reference Pappa, Ntella, Giannakas, Giannakoulis, Papoutsi and Katsaounou7,Reference Charney, Katz, Southwick and Charney33–Reference Muller, Hafstad, Himmels, Smedslund, Flottorp and Stensland35 Not surprisingly, the meandering and persisting course of the pandemic in the USA shows that repeated and chronic exposure to stress may lead to more severe trauma and psychological stress.Reference Milliken, Auchterlonie and Hoge36 As the Covid-19 pandemic continues, brief interventions to increase treatment-seeking intentions have the potential to increase the likelihood of seeking care.Reference Amsalem, Dixon and Neria37

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample is limited to Amazon Mechanical Turk participants, who might differ demographically or clinically from the healthcare population, and it includes mostly nurses (68%) and women (74%), thus limiting generalisability. Second, we assessed openness to seeking help, the reporting of which may be subject to social desirability, but not actual treatment-seeking. However, previous studies showed that a change in attitudes leads to a change in behaviour.Reference Perinelli and Gremigni38 Future studies should ask about previous help-seeking and knowing someone who had sought help, and determine respondents’ actual seeking of mental health services. Third, the clinical assessments were self-report questionnaires, which are subject to over- or under-reporting, and all of which were designed for screening rather than confirmatory diagnostic purposes.Reference Webb and Sheeran39 Finally, our study evaluated the 30-day effect of our brief video intervention, but further studies should assess longer-term sustainability.

Implications

The high proportion of healthcare workers surveyed in this study who reported symptoms of probable generalised anxiety, depression and/or PTSD emphasises the need for intervention aimed at increasing treatment-seeking among US healthcare workers. A three-minute online social contact-based video intervention effectively increased self-reported treatment-seeking intentions among healthcare workers. This intervention had a greater impact on nurses, an effect seen solely in the video groups, suggesting that the choice of video protagonist should reflect the intended audience. Educators and employers should consider using such interventions proactively to encourage nursing/medical students and employees to search for help and provide mental health treatment resources for those who need them.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.54.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

We thank the video participant who shared her story and contributed to treatment-seeking intentionality.

Author contributions

D.A., A.L. and Y.N. contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was carried out by D.A.. D.A. and A.L. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of results. All authors reviewed the results, were involved in draft manuscript preparation and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.