Background

Evidence suggests that retrospectively self-reported trauma is associated with a greater risk of psychopathology in adulthood than prospective measures of trauma, such as court records.Reference Danese and Widom1,Reference Reuben, Moffitt, Caspi, Belsky, Harrington and Schroeder2 One possible explanation for the increased risk associated with retrospective reports is that they may be more open to differences in the interpretation of experiences as traumatic, the likelihood of recalling these experiences as traumatic and the willingness to report traumatic events. These differences in reporting may be influenced by individual reporter differences, such as personality traits, psychopathology or cognitive biases.Reference Reuben, Moffitt, Caspi, Belsky, Harrington and Schroeder2 In turn, these characteristics could also reflect or affect risk of psychopathology. In accordance with this, evidence suggests that retrospective self-reports are partly under genetic influence.Reference Schulz-Heik RJ, Rhee, Silvern, Lessem, Haberstick and Hopfer3,Reference Warrier, Kwong, Luo, Dalvie, Croft and Sallis4 Similarly, reporter characteristics including personality traits, psychopathology and cognitive biases have also been found to have a heritable component.Reference Vukasović and Bratko5–Reference Zavos, Rijsdijk, Gregory and Eley7 As such, the heritability of reporter characteristics could, in part, explain the genetic component identified for retrospectively reported trauma.Reference Coleman, Peyrot, Purves, Davis, Rayner and Choi8,Reference Dalvie, Maihofer, Coleman, Bradley, Breen and Brick9 In a recent study of female nurses, polygenic scores representing individual genetic liability for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depression, neuroticism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) were all associated with a higher likelihood of reporting childhood abuse in mid-life.Reference Ratanatharathorn, Koenen, Chibnik, Weisskopf, Rich-Edwards and Roberts10 These findings suggest that associations between retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma and later psychopathology are partly confounded by genetic predisposition to these outcomes, which influence both the likelihood of reporting traumatic events and of developing a disorder. However, these methods do not take into account the effect of environmental risk. As well as acting through the individual directly, genetics also have an impact on a person's environment. This process, termed gene–environment correlation (rGE), occurs when genetic factors influence both an individual's liability for a trait and the environments that they are exposed to.Reference Plomin, DeFries and Loehlin11

There are three mechanisms of rGE: passive, active and evocative. Passive rGE describes the association between the genotype that a child inherits and the rearing environment that the parents create. Evocative rGE refers to an individual's genetically influenced behaviours instigating certain responses from others. Active rGE describes the association between an individual's genetically influenced traits and the environments that they select. Therefore, part of the association between polygenic scores for psychiatric traits and self-reports of trauma may be accounted for by genetic influences on the environment. However, when investigating these associations without considering environmental factors, the effects of rGE cannot be disentangled from the direct effects of genetics on interpretation and reporting.

Aims

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether the associations between heritable reporter characteristics and retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma are accounted for by rGE. We investigated whether polygenic scores for cognitive, personality and psychopathological traits were associated with retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma. To assess the presence of rGE, we investigated whether these associations remain after controlling for environmental adversity across development. We hypothesised that findings of rGE would suggest increased risk of experiencing traumatic events. On the other hand, if associations are found while accounting for environmental adversity, this would suggest differences in appraisal of trauma linked to genetic factors.

Method

Participant characteristics

The Twins Early Development Study (TEDS)Reference Rimfeld, Malanchini, Spargo, Spickernell, Selzam and McMillan12 is a longitudinal study of over 15 000 twin pairs born in England and Wales between 1994 and1996, identified through birth records. At 13 time points between birth and age 21, TEDS has collected data on the home environment, physical and mental health, personality and cognitive abilities. The study participants included a subset of unrelated TEDS twins who had both genetic data and data on self-reported trauma at age 21 (n = 3963).

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval for TEDS has been provided by the King's College London Ethics Committee (reference: PNM/09/10–104). Written informed consent was obtained from parents and from twins themselves from age 16 onwards prior to each wave of data collection.

The demographic characteristics of the study participants as compared with the full TEDS cohort are shown in Table 1. The study sample had a higher proportion of female participants (62%) and White individuals (99%) compared with the full TEDS cohort, with Cramer's V indicating these differences were of small effect (V = 0.10–0.12). Differences in zygosity and family socioeconomic measures were of less than small effect size (V < 0.10). The greater proportion of female participants in the study sample reflects the gradual decrease in male participants in recent waves of TEDS data collection.Reference Rimfeld, Malanchini, Spargo, Spickernell, Selzam and McMillan12,Reference Rimfeld, Malanchini, Packer, Gidziela, Allegrini and Ayorech15 At first contact, participants’ ethnicity was reported by parents, from the categories of ‘Asian’, ‘Black’, ‘Mixed race’, ‘White’ and ‘Other’. We acknowledge that these categories are limited for representing participant identity. The full TEDS cohort remains fairly representative of the ethnic diversity of UK families in the mid-1990s when the twins were born.Reference Rimfeld, Malanchini, Packer, Gidziela, Allegrini and Ayorech15 The high proportion of participants in the study sample who identified as White corresponds to all genotyped participants being of European ancestry.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) study participants (n = 3963), as compared with the full TEDS cohort and UKa

V = Cramer's V.

a. UK data from the 2000 General Household Survey13 are used rather than more recent data because they provide more appropriate comparisons for TEDS twins who were born 1994–1996. The percentage of monozygotic twins represents the average percentage in England and Wales from 1994 to 1996.Reference Imaizumi14 A-levels are the national educational exam taken at 18 years of age in the UK. χ2 is Pearson's χ2 with 1 degree of freedom.

b. We acknowledge that these data are limited for representing participant identity, as discussed in text.

Measures

Childhood trauma

Retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma was assessed during the TEDS-21 wave of data collection.Reference Rimfeld, Malanchini, Packer, Gidziela, Allegrini and Ayorech15 Experiences of trauma were measured using eight items assessing emotional and physical abuse, derived from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children ‘Life at 22+’ questionnaireReference Houtepen, Heron, Suderman, Tilling and Howe16 (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.207). Participants reported how frequently they experienced these types of abuse during their childhood, on a scale of ‘Never’ (0) to ‘Very often’ (4), with total scores ranging from 0 to 32. The average total score in the study sample was 5.2 (s.d. = 4.5).

Genome-wide polygenic scores

Genome-wide polygenic scores for 21 relevant psychiatric, cognitive, anthropometric and personality traits derived from the largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) were selected (Supplementary Table 2). The majority of these polygenic scores had been previously constructed in TEDS for use in the prediction of cognitive and behavioural traits.Reference Gidziela, Rimfeld, Malanchini, Allegrini, McMillan and Selzam17–Reference Allegrini, Selzam, Rimfeld, von Stumm, Pingault and Plomin19 Where TEDS had formed part of the discovery GWAS sample, polygenic scores were created from summary statistics generated without the contribution of the TEDS cohort. For example, polygenic scores for intelligence were created from summary statistics derived from a subset of the GWAS discovery sample (Supplementary Table 2). DNA samples obtained from saliva and buccal cheek swabs were genotyped on either Affymetrix GeneChip 6.0 or Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome-8v1.2 arrays and underwent common quality control procedures. Full genotyping and quality control processes as detailed elsewhereReference Selzam, McAdams, Coleman, Carnell, O'Reilly and Plomin20 are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Polygenic scores were constructed using LDpred,Reference Vilhjálmsson, Yang, Finucane, Gusev, Lindström and Ripke21 with the proportion of genetic markers assumed to be contributing to the trait set to 1.Reference Selzam, Ritchie, Pingault, Reynolds, O'Reilly and Plomin22

Environmental measures

Environmental factors capturing environmental adversity across development were selected, including maternal depression,Reference Doidge, Higgins, Delfabbro and Segal23 economic disadvantage,Reference Doidge, Higgins, Delfabbro, Edwards, Vassallo and Toumbourou24 family cohesion,Reference Stith, Liu, Christopher Davies, Boykin, Alder and Harris25 parental feelings or discipline,Reference Brown, Cohen, Johnson and Salzinger26 negative life eventsReference Brown, Cohen, Johnson and Salzinger26 and peer difficultiesReference Radford, Corral, Bradley and Fisher27 (Supplementary Table 3). These measures have previously been associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma, and indicate the experience of challenging early environments that tend to co-occur with childhood trauma.

Early adversities were separated according to whether they were parent- or self-reported, as reports by parents and children typically show poor agreement, partly because they provide different perspectives on the family environment.Reference Sessa, Avenevoli, Steinberg and Morris28 Participants were included providing that they had data for more than 75% of variables, those missing more than 25% of variables at each age were excluded. As the nature of rGE effects vary across development, environmental adversities in pre-school (age 1–4), middle childhood (7–10) and early adolescence (12–16) were summed to create composite scores of environmental adversity in each developmental period. The collection of self-reported measures began from age 9, resulting in five composite scores: parent-reported environmental adversities in pre-school, middle childhood and early adolescence, and self-reported environmental adversities in middle childhood and early adolescence (Supplementary Table 3).

Data handling

All predictors were standardised by centring and dividing by 2 s.d.s, resulting in a mean of 0 and a s.d. of 0.5, using the rescale function from the R package ‘arm’ (Supplementary Table 4).Reference Gelman29

To account for participants with missing environmental adversity composite scores, multiple imputation was conducted using the R package ‘mice’, using a prediction matrix containing the five composite scores, polygenic scores, outcomes and covariates.Reference Moons, Donders, Stijnen and Harrell30,Reference Zhang31 The average missingness of environmental variables in the sample was 3.6%, the number of imputed data-sets was 25, and the number of iterations was 20.Reference van Buuren32 All analyses were then performed through ‘mice’ with the imputed data-sets.

Analysis

First, we assessed whether polygenic scores for psychiatric, cognitive, anthropometric and personality traits were associated with self-reported childhood trauma. Univariable linear regression models were run to assess the association between each polygenic score and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. Subsequently, a multivariable linear regression model was run, including all 21 polygenic scores.

Second, we tested the assumption that the composite scores of environmental adversity across development were associated with self-reported childhood trauma, as predicted from previous literature. Univariable linear regression models were run to assess the associations between each of the five environmental adversity composite scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. Then a multivariable linear regression model was run, including all five environmental adversity composite scores.

Finally, to assess the presence of rGE, we investigated whether the associations between polygenic scores and self-reported childhood trauma remained after controlling for environmental adversity across development. To do so, we regressed retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma on both the polygenic scores and the five composite scores of environmental adversity across development in one multivariable linear regression model.

As a planned control, we assessed the specificity of these findings to retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma, by comparing associations with self-reports of contemporaneous traumas in adulthood.

All analyses were conducted using the lm function within ‘mice’, in R version 4.0.3.33 Analyses were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework prior to receiving the data-set (https://osf.io/vk5jf/).

Covariates and multiple testing

In all analyses, birth year, gender and genotyping batch were included as covariates. In analyses of polygenic scores, the first 10 genetic principal components were also included. Corrections for multiple testing were applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment, with a threshold of 0.05, which controls for the expected proportion of false positives among the significant results.Reference Benjamini and Hochberg34

Results

Association between polygenic scores and retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma

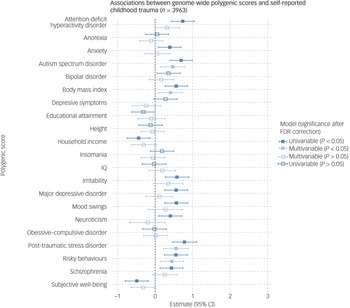

Figure 1 shows the associations between genome-wide polygenic scores for psychiatric, cognitive, anthropometric and personality traits with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma at age 21. Univariable models were used to assess the associations between each of the polygenic scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. A multivariable model including all 21 polygenic scores was then used to assess the independent associations between the polygenic scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. Effect sizes (β) are shown for a 2 s.d. increase in polygenic scores.

Fig. 1 Associations between genome-wide polygenic scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma at age 21, derived from univariable and multivariable linear regression models (n = 3963).

In univariable linear regression models, polygenic scores for ADHD, anxiety, ASD, body mass index (BMI), irritability, major depressive disorder, mood swings, neuroticism, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), risky behaviours and schizophrenia were positively associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma after FDR correction for multiple testing. A 2 s.d. increase in these polygenic scores was associated with an increase in self-reported childhood trauma ranging from β = 0.39 (95% CI 0.09–0.69) for anxiety to β = 0.79 (95% CI 0.46–1.11) for PTSD (Supplementary Table 5). Polygenic scores for household income (β = −0.44, 95% CI −0.74 to −0.13) and subjective well-being (β = −0.48, 95% CI −0.79 to −0.18) were negatively associated with self-reported childhood trauma. When all polygenic scores were included in a multivariable linear regression model, only scores for ASD (β = 0.47, 95% CI 0.15–0.80), BMI (β 0.41–95% CI 0.09, 0.73), PTSD (β = 0.56, 95% CI 0.23–0.89) and risky behaviours (β = 0.45, 95% CI 0.14–0.76) remained independently associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma.

Association between environmental adversity across development and retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma

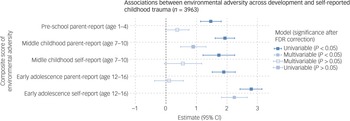

Figure 2 shows the associations between the five composite scores of parent- and self-reported environmental adversity in pre-school, middle childhood and early adolescence with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma at age 21. Univariable models were used to assess the associations between each of the environmental composite scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. A multivariable model including all five environmental composite scores was then used to assess the independent associations between the composite scores and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. Effect sizes (β) are shown for a 2 s.d. increase in composite scores.

Fig. 2 Associations between composite scores of parent- and self-reported environmental adversity across development and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma at age 21, derived from univariable and multivariable linear regression models (n = 3963).

As anticipated, in univariable linear regression models all five composite scores of environmental adversity were associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. A 2 s.d. increase in any composite score was associated with an increase in self-reported childhood trauma ranging from β = 1.47 (95% CI 1.13–1.81) for parent-reported environmental adversity in pre-school to β = 2.78 (95% CI 2.42–3.15) for self-reported environmental adversity in early adolescence.

When all composite scores were included in a multivariable linear regression model, only two remained independently associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. Self-reported environmental adversity in early adolescence, which captured home chaos, parental feelings and discipline, parental monitoring and control, life events and peer victimisation (Supplementary Table 3), was most strongly associated with self-report childhood trauma (β = 2.24, 95% CI 1.83–2.66). Parent-reported environmental adversity in middle childhood also remained associated, which captured changes in parental marital status or household finances, parental feelings and discipline, life events and child relationship problems (β = 0.90, 95% CI 0.48–1.32).

Independent associations between polygenic scores and environmental adversity across development with retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma

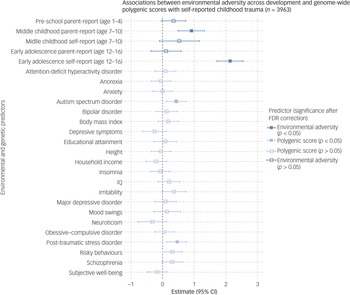

To assess the presence of rGE, we investigated whether the associations between polygenic scores and self-reported childhood trauma remained after controlling for environmental adversity across development (Fig. 3). We regressed retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma on the 21 polygenic scores and the five composite scores of environmental adversity across development in one multivariable model. Effect sizes (β) are shown for a 2 s.d. increase in composite scores and polygenic scores.

Fig. 3 Associations between composite scores of parent- and self-reported environmental adversity across development and genome-wide polygenic scores with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma at age 21, derived from a multivariable linear regression model (n = 3963).

In the model of environmental composite scores and polygenic scores, only parent-reported environmental adversity in middle childhood (β = 0.91, 95% CI 0.49–1.33), self-reported environmental adversity in early adolescence (β = 2.13, 95% CI 1.72–2.55) and the polygenic scores for ASD (β = 0.43, 95% CI 0.13–0.74) and PTSD (β = 0.46, 95% CI 0.15–0.77) remained independently associated with retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma.

Planned control analyses assessing the specificity of the findings to retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma indicated a different pattern of associations for self-reports of contemporaneous traumas in adulthood (Supplementary Table 6). Self-reported environmental adversity in early adolescence was associated with both self-reported partner abuse (β = 2.00, 95% CI 1.45–2.54) and major life events (β = 1.26, 95% CI 0.90–1.62). Parent-reported environmental adversity in pre-school (β = 0.41, 95% CI 0.10–0.72) was additionally associated with self-reported major life events. For both self-reports of contemporaneous adulthood traumas, the polygenic scores for educational attainment and major depressive disorder were the most strongly associated, however, no polygenic scores remained significantly associated with either of the self-reported adulthood traumas after FDR correction for multiple testing.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study we examined polygenic scores associated with retrospective self-reports of childhood trauma and whether these associations remain after controlling for environmental adversity across development. Retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma was independently associated with polygenic scores for ASD, BMI, PTSD and risky behaviours. When environmental adversity was controlled for, only the polygenic scores for ASD and PTSD remained significantly associated.

Interpretation and comparison with findings from other studies

The robust association between retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma and polygenic scores for ASD replicates previous findings from two cohorts.Reference Ratanatharathorn, Koenen, Chibnik, Weisskopf, Rich-Edwards and Roberts10,Reference Warrier and Baron-Cohen35 There are two possible explanations for this finding. One explanation is rGE, when genetic factors influence both an individual's liability for ASD and their environments.Reference Plomin, DeFries and Loehlin11 Genetic liability for autistic traits may increase difficulty with social interaction, which could evoke adverse reactions, such as neglect or abuse, from others (evocative rGE), or increase the likelihood of being in dangerous environments (active rGE).Reference Warrier and Baron-Cohen35

Consistent with this explanation, another study found over transmission of genetic risk for reporting childhood trauma from parents to children with autism but not to their siblings who did not have autism.Reference Warrier, Kwong, Luo, Dalvie, Croft and Sallis4 This suggests that the increased genetic risk of reporting childhood maltreatment in individuals with ASD may be partly explained by increased active and evocative rGE. A second explanation is that individuals with high genetic risk for ASD may be more sensitive to experiencing, interpreting and/or reporting an event as traumatic.Reference Warrier and Baron-Cohen35 This explanation is more in line with the results of the present study, as the association between the polygenic score for ASD and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma remained significant after controlling for environmental adversity in childhood and adolescence. Consistent with this explanation, the polygenic score for ASD was not found to be associated with prospectively measured childhood trauma.Reference Sallis, Croft, Havdahl, Jones, Dunn and Davey Smith36 Indeed, adults with ASD report a broad range of life events as being traumatic.Reference Rumball, Happé and Grey37 Furthermore, they are at increased risk of developing a trauma-related disorder, even following events that would not meet the DSM38 criteria for trauma.Reference Rumball, Happé and Grey37 This explanation does not imply that these events were not traumatic, as trauma is not only the nature of an event but also how it is experienced and recalled by the individual. Rather, it provides a framework for understanding how the subjective experience relates to the outcomes of reported trauma.

The finding that the polygenic score for PTSD remained associated with self-report childhood trauma after controlling for environmental adversity also indicates that genetic risk for PTSD may influence the subjective experience or reporting of traumatic events. This is in line with previous research showing that the PTSD polygenic score is not associated with trauma exposure severity.Reference Waszczuk, Docherty, Shabalin, Miao, Yang and Kuan39 This provides evidence against rGE, whereby genetic risk for PTSD would be expected to contribute to greater exposure to traumatic events.Reference Waszczuk, Docherty, Shabalin, Miao, Yang and Kuan39 These findings instead imply that individuals with genetic risk for PTSD may be more likely to interpret experiences as being traumatic. Indeed, PTSD is associated with increased processing of negative information compared with neutral stimuli, including greater attention towards and difficulty disengaging from negative stimuli, greater likelihood of interpreting neutral stimuli as threatening, and a bias towards remembering trauma-relevant information.Reference Bomyea, Johnson and Lang40 These information processing biases may increase the likelihood of reporting events as being traumatic, a necessary criterion for a PTSD diagnosis.38

Our finding that polygenic scores for BMI and risky behaviours were no longer significant once controlling for environmental adversity likely reflects overlap in some of the mechanisms that these variables capture. The polygenic score for risky behaviours was derived from the first principal component of behaviours across the four domains of automobile speeding propensity, number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week, whether one has ever been a smoker, and number of lifetime sexual partners, capturing a general tendency towards risk taking.Reference Linnér R, Biroli, Kong, Meddens, Wedow and Fontana41 Risk-taking behaviours and high BMI are anticipated to share behavioural mechanisms, owing to common associations with impulsivity, self-control and reward-seeking behaviours.Reference Clifton, Perry, Imamura, Lotta, Brage and Forouhi42 These results suggest that rGE may account for some of the association between polygenic scores for these traits and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. This could be through passive rGE, for example, children in households where parents engage in more risky behaviours, such as alcohol misuse, are both more likely to experience childhood adversityReference Dube, Anda, Felitti, Croft, Edwards and Giles43 and inherit a predisposition to these behaviours. These associations may also be influenced by evocative rGE, for example, impulsive behaviour in children is associated with negative parenting and harsh discipline strategies.Reference Gershoff44 In line with these mechanisms, our findings suggest that some of the effects of genotype on self-reporting of trauma are no longer present once the effects of genotype on the environment are controlled for.

Associations between retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma and genetic risk for ASD, BMI, PTSD and risky behaviours reflect the previously identified shared genetic architecture of these traits.Reference Dalvie, Maihofer, Coleman, Bradley, Breen and Brick9,Reference Clifton, Perry, Imamura, Lotta, Brage and Forouhi42 However, unlike previous research, we did not find associations between retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma and polygenic risk for other psychopathological and personality traits. In a cohort of female nurses, in addition to the polygenic score for ASD, associations were found between self-reported childhood trauma and polygenic scores for major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, neuroticism, schizophrenia and ADHD.Reference Ratanatharathorn, Koenen, Chibnik, Weisskopf, Rich-Edwards and Roberts10 A likely reason for this inconsistency is that the larger sample size of the nurse cohort (n = 11 315) resulted in higher power to detect small effects (OR range 1.05–1.19). Nevertheless, in the study of nurses, when polygenic scores were created with only variants uniquely associated with each trait, the score most strongly associated with reported childhood trauma was that of ASD.Reference Ratanatharathorn, Koenen, Chibnik, Weisskopf, Rich-Edwards and Roberts10 Therefore, both studies indicate a robust association between genetic liability for ASD and retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma, independent of genetic liability for other traits, as assessed through polygenic scores. Planned control analyses indicate that this effect is specific to retrospectively reported childhood trauma, as the same associations were not observed for self-reports of contemporaneous traumas in adulthood.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the use of composite scores of environmental adversity, meaning it is difficult to infer which specific adversities within each developmental period are driving associations with self-reported trauma. Furthermore, not all types of environmental adversity were assessed at each time point. Prenatal complications and maternal depression were only assessed in pre-school by parent-report, relationship problems were only assessed in middle childhood by parent-report, and peer victimisation was only assessed in early adolescence. Therefore, associations specific to a particular developmental stage could be confounded by the types of adversity assessed at that time. However, this approach enabled the inclusion of a broader scope of environmental adversities across development. Another limitation was the conceptualisation of childhood trauma as physical or emotional abuse. Childhood trauma can take several other forms, including physical and emotional neglect and sexual abuse, which are associated with differential reporting patterns, heritability estimates and outcomes.Reference Danese and Widom1,Reference Schulz-Heik RJ, Rhee, Silvern, Lessem, Haberstick and Hopfer3,Reference Ratanatharathorn, Koenen, Chibnik, Weisskopf, Rich-Edwards and Roberts10 Nevertheless, different types of childhood trauma are found to have substantial genetic overlap.Reference Warrier, Kwong, Luo, Dalvie, Croft and Sallis4

Finally, female participants and participants self-identifying as White were over-represented in the study sample, which may have an impact on the applicability of these findings to the general population. In the case of gender representativeness, this reflects greater retention of female participants compared with male ones in TEDS from the early teenage years onwards. To help mitigate this selection bias, gender was included as a covariate in all analyses. Ethnic diversity is a more pressing issue as only participants of European ancestry are currently included in the genotyped subset of TEDS participants, resulting in 99% of the study participants identifying as White. This is because many polygenic scores having poor predictive performance in individuals from more diverse ancestry groups, as the GWAS that these scores are derived from only include individuals of European ancestry in order to increase homogeneity. The need for large-scale GWAS in diverse human populations, and polygenic scores with predictive power across ancestral groups, is an immediate priority for research in this field.Reference Duncan, Shen, Gelaye, Meijsen, Ressler and Feldman45

Implications

These findings have clear implications for understanding of retrospectively self-reported childhood trauma. They indicate that self-reports of trauma are associated with heritable reporter characteristics. This reinforces the importance of using genetically sensitive designs when assessing associations between self-reported experiences and later-life outcomes. Research that does not account for the confounding role of genetics should take particular care not to draw causal inferences. In contrast, genetically sensitive designs can help disentangle the complex mechanisms through which self-reports of childhood trauma are linked with poor outcomes, informing preventative and therapeutic strategies. Clinically, these findings suggest that an increased genetic liability for ASD and PTSD might bias the perception of life events, making individuals more sensitive to experiencing, interpreting and/or reporting an event as traumatic. Therefore, a broad range of experiences may be considered traumatic for these individuals, who may need clinical support even if diagnostic criteria for trauma are not met.38 It will be important to identify the specific cognitive biases linked to genetic liability for ASD and PTSD. A better understanding of the subjective experience of trauma will help identify possible vulnerability factors for psychopathology and targets for novel treatments.Reference Danese and Widom1 The use of polygenic scores alongside other established factors could help guide treatment choices based on such cognitive biases. Finally, it is important to stress that these results show only associations with self-reported experiences and do not imply that genetic predisposition for these traits would cause a person to experience adversity.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.207.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study came from the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS). Eligible researchers can apply for access to the TEDS data: https://www.teds.ac.uk/researchers/teds-data-access-policy.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the ongoing contribution of the participants in the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) and their families.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in formulating the research questions and devising the analysis plan. Analysis was led by A.J.P. with support from K.L.P., J.R.I.C. and M.S. All authors contributed to interpretation of results. A.J.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback on manuscript drafts and approved the final version. T.C.E. and A.D. jointly supervised this work.

Funding

TEDS is supported by a programme grant to T.C.E. and G.B. from the UK Medical Research Council (MR/V012878/1 and previously MR/M021475/1). A.D. is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. A.J.P. is supported by an ESRC studentship. M.S. and A.R.T.K. are funded by NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre studentships. J.-B.P. is supported by the Medical Research Foundation 2018 Emerging Leaders 1st Prize in Adolescent Mental Health (MRF-160-0002-ELP-PINGA). J.R.B. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Sir Henry Wellcome fellowship (grant 215917/Z/19/Z). This study represents independent research part funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.