1. Introduction

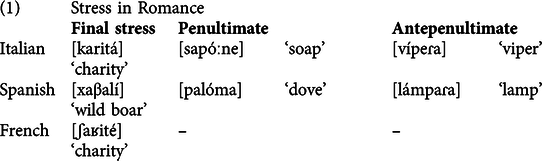

It is widely believed that there is no sub-phrasal stress in French,Footnote 2 at the ‘word’ ‘stem’ or ‘root’ (Posner, Reference Posner1997).Footnote 3 Defined in standard terms, Latin and other Romance languages all show evidence for a right-aligned foot, quantity-sensitive in the case of Latin and Italian and more ambiguously so in Spanish (Hualde, Reference Hualde2005). French is typically described as non-quantity sensitive and it has been argued not to possess foot structure at all (Özçelik, Reference Özçelik2016) (though see: Durand, Reference Durand1976; Reference Durand1980; 1986; Selkirk, Reference Selkirk and Fretheim1978; Charette, Reference Charette1991; Eychenne, Reference Eychenne2006; Goad and Buckley, Reference Goad and Buckley2006; Durand and Eychenne, Reference Durand and Eychenne2007). Whatever the case is regarding foot-structure, French certainly does not split its lexicon into oxytonic, paroxytonic, and proparoxytonic forms, that is to say that French has no contrastive stress.

Key changes from Latin to French saw the loss of quantity-sensitivity in the third–fourth century, along with monophthongization and the attrition of stressless syllables (Vaissière, Reference Vaissière1996).

In Contemporary French, the domain of prominence in French is not assumed to be the word. Instead, French prominence is commonly described at the level of the phrase (Delattre, Reference Delattre1966; Dell, Reference Dell, Dell, Hirst and Vergnaud1984; Jun and Fougeron, Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000; Hyman, Reference Hyman and van der Hulst2014), in the form of a phrase-final boundary tone (Rossi, Reference Rossi1980; Vaissière, Reference Vaissière, Cutler and Ladd1983; Martin, Reference Martin1987; Féry, Reference Féry and Sternefeld2001), or an intonational pattern applied at the ‘accentual phrase’: LHiLH* (Jun and Fougeron, Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000).

The synchronic lack of underlying word-level stress is confirmed experimentally by the effect of ‘stress deafness’ (Dupoux et al., Reference Dupoux, Pallier, Sabastian-Galles and Mehler1997; Peperkamp and Dupoux, Reference Peperkamp, Dupoux, Gussenhoven and Warner2002). As a reviewer points out, Peperkamp and Dupoux (Reference Peperkamp, Dupoux, Gussenhoven and Warner2002) do not preclude word-level prominence in French, even citing a phonetic study where due to its non-contrastivity, it can be used by speakers for lexical segmentation (Rietveld, 1980). However, the clear implication of their work is that this word-level stress is not a part of the underlying form.

Phonologically, tone and stress are often insightfully grouped together as ‘accent’. In some languages (e.g. Saramaccan (Eng. Creole)), a high pitch marks the correspondingly stressed position of English words: [bróðɚ] > baráda > barada > [baáa] (Aceto, Reference Aceto1996; Schumann [1778]). Likewise, in some tonal languages, such as Mandarin Chinese, function words or thematic prefixes do not carry a tone, analogous to the functional lexicon in English that does not bear stress.

If French has no underlying phonological word-stress at all, and its boundary tone is a phrasal tonal/intonational phenomenon, French might be argued to have neither phonological word-stress, nor word-level tonal prominence. Exceedingly few languages meet this description: Hungarian (Peperkamp and Dupoux, Reference Peperkamp, Dupoux, Gussenhoven and Warner2002), Ambonese Malay (Maskikit-Essed and Gussenhoven, Reference Maskikit-Essed and Gussenhoven2016), Yowlumne (Newman, Reference Newman1944; Archangeli, Reference Archangeli1984–1985), Kuki-Thaadow (Hyman, Reference Hyman and Floricic2010), and Rotokas (Firchow, Reference Firchow1974). There are also often poorly described and may be misanalysed. It is vital that the typological significance of French is properly understood.

2. Final strength in French

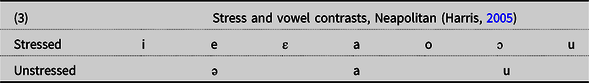

It is a straightforward typological observation that stressed positions in words contains a greater number of vocalic contrasts than stressless positions (Crosswhite, Reference Crosswhite2001). Stress licensing a greater number of contrasts even forms an unchallenged implicational universal: no system has a greater number of vocalic contrasts in unstressed positions than it does in stressed positions.

French has essentially this same pattern of vowel contrasts in stressed positions (Tranel, Reference Tranel1987: 58-59), though this is not immediately obvious, it requires analysis. Though the ultimate explanation of the pattern is diachronic, the distribution forms a synchronic strength-based asymmetry available to the learner.

In French, open and close-mid vowels do not initially appear to be underlyingly contrastive. Traditional descriptions of French assume that mid vowels are regulated by a rule called the loi de position (Morin, Reference Morin1986). Close-mid vowels [e, o, ø] are found in open syllables and the open-mid vowels [ε, ɔ, œ] are found in closed syllables. For a recent description of its phonetic characterization see Storme (Reference Storme2017).

There are some systematic exceptions to the loi de position, such as open-mid vowels before non-final /ʁ/ (Tranel, Reference Tranel1987),Footnote 4 as well as other allophonies (assimilations and lengthening effects). However, what is of interest to us here is that the word-final position habitually hosts a contrast between open and close-mid vowels. This is the only context where there are minimal pairs for mid vowels.Footnote 5

It is important to eliminate the confound of underlying consonants that are not pronounced on the surface. This is because many forms with the ‘unexpected’ open-mid vowels in open syllables come historically from consonant-final forms (still shown orthographically in (5)), moreover, in many of these forms, the consonant still alternates with zero in liaison contexts: /epε<s>/ > [epesi] épaissi ‘thicken’. The quality of this consonant is not only ‘t’, so it cannot be inserted by epenthesis, unlike: [kaju] caillou ‘stone’ vs. [kajutø] caillou+eux (stone + adj) ‘stony’) (Pagliano, 2003). Since the quality of these consonants is unpredictable, they must be root-final consonants.Footnote 7 One has to eliminate the possibility that these are allophonic products of the loi de position triggered by underlying final consonants that close the syllable.

Synchronically, a final floating consonant does not determine vowel quality.

Firstly, not all final-open vowels are synchronically followed by a floating consonant. Though items like [lέ] lait ‘milk’ once had an etymological ‘t’, this final consonant has been entirely lost. It does not even surface in hiatus contexts: [lə.lε.ε.blã] le lait est blanc ‘the milk is white’ (cf. [pʁέ] prêt ‘ready’ > [pʁέtapaʁtiʁ] ‘ready to leave’).

Secondly, even when there is a final floating consonant, the floating consonant does not close a syllable. There are many words which end in final close-mid vowels and a floating consonant. One example would be ‘pot’ which has a close-mid vowel followed by a floating /t/. The floating consonant surfaces in liaison contexts: [po.to.fǿ] ‘pot-au-feu’, but in isolation the item is pronounced [po] *[pɔ] ‘pot’.

The same argument can be made for many other items with a range of different underlying consonants.Footnote 8 Take for instance, /mjø<z>/ mieux ‘better’. This undergoes ‘z’ liaison: [mjøzέtχ] mieux être ‘better to be’, but in isolation it surfaces as close-mid: [mjø]. Or one could take /tʁo<p>/ trop ‘too much’, which undergoes ‘p’ liaison: [tʁopepε] trop épais ‘too thick’, but in isolation also surfaces with a close-mid vowel: [tʁo] trop ‘too (much)’.

The final context always has the widest set of underlying contrasts.

Scheer (2004) distinguishes three different sources of phonological strength: (a) positional, (b) prosodic (Harris, 1994), (c) feature sharing (Honeybone, Reference Honeybone2002, Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005).

Aspiration in English can be taken as an example of the inherent strength of the initial position. Usually seen as an expression of prosodic strength (Harris, 1994) due to its pretonic distribution (8a-b), however, aspiration is also found in initial unstressed position (8d).

The inherent strength of the initial position has been shown experimentally (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Nevins and Levine2012), and there is a strong statistical universal where neutralization targets word-ends over word-beginnings (Wedel et al., to appear).

The final position is inherently weak. Typologically, there are very few clearly positional phonological word-final strengthening effects.Footnote 9 Word-final edges when not protected by stress tend to delete diachronically (see 2). Moreover, all things being equal, we see contrast neutralization in final position, unless it is stressed. In Brazilian Portuguese, for instance, where the stressed position can hold 7 vowels, the pretonic position (medial or initial but unaccented) can hold 5, but word-finally it can have only 3.

The final position is inherently weak, however, it can be made strong with stress. I suppose this is what happens in French. An example of stress conveying strength to final syllables comes from Standard Tuscan Italian.

As shown beneath, Italian has seven vowels in stressed position (10a). The internal (initial and medial) unstressed position can hold a five-way contrast (10b). The final unstressed position is inherently weaker with only a four-way contrast (10c). Unstressed positions cannot hold open-mid vowels. The final position can be strong as long it is stressed (10d).

The final position is inherently weaker than medial positions, but stress overcomes positional weakness. French is taken to be the same, and it makes it more coherent from a theoretical typological perspective (cf. Tranel (Reference Tranel1987)). This implies that French has underlying stress in roots; underlying because its expression is in terms of underlying vowel contrasts; despite lacking lexical contrastivity.Footnote 11

3. [ə]-Adjustment

Final prominence in the underlying distribution of vowels is argued to be an expression of phonological stress. In addition to this static distribution, French also presents an allophonic alternation that I will claim, following Charette (Reference Charette1991: 172), is stress-conditioned. This process involves the strengthening of schwa in final position: [kʁəvé] crever ‘die.INF’ vs. [kʁέv] crève ‘die.1P.PRES.IND’; so-called ə-adjustment.

Dell (Reference Dell1973; 1980) collapses ə-adjustment with another rule called e-adjustment: [netwajé] nettoyer ‘to clean’, [nέt] net ‘neat’, into a larger rule: Closed Syllable Adjustment (CSA) (Dell, Reference Dell1973; 1980).Footnote 12 Arguments against this conflation are presented in Tranel (Reference Tranel1984) but they are not strictly relevant here, so I will only present the strictly necessary data for ə-adjustment.

In isolation these may seem to support phrasal stress: [(il + (aʃət))Pph] > [ilaʃέt] il achète ‘he buys’. However, if [ə]-adjustment was conditioned by phrasal stress, it should not apply in non-phrase-final position, this prediction is categorically wrong.

The derivation in (12) shows that a grammar with only phrasal-stress mispredicts the output of forms such as these: *[il-apəl-ʒã] ‘he calls Jean’. Conversely, the “word”-stress analysis (12b) generates the correct outcome: [ilapέlʒã] ‘he calls Jean’.Footnote 15

The pattern shown in (12b) cannot be explained by secondary stress. Following Özçelik (Reference Özçelik2016)’s insightful discussion, it is clear that secondary stress in French truly does apply at the phrasal level, specifically at phrasal margins: (a) màrie-róse *marí-róse, (b) èlephant grís *elephánt grís ‘grey elephant’, (c) l’àutomobile vérte ‘the green car’, (d) l’àutomobile violétte *l’automobìle violétte ‘the purple car’.

A reviewer points out that there is a syllable structure-driven alternative account. They suggest that Dell (Reference Dell1973; 1980) analyses the process as a ban on schwa in closed syllables. If this was the case, it would undercut the stress-based explanation. However, Dell’s rule is actually not a purely syllable-structure one.

First off, the ə-adjustment in [i.la.pέ.la.na.ïs] ‘he calls Anaïs’ is not a closed syllable, so the analysis clearly cannot be surface true. In fact, Dell’s analysis requires very specific extrinsic word ordering that applies at the word-level. Investigating the rule in relation to other rules, primarily schwa deletion, creates a sort of a paradox that is resolved by introducing morpheme-structure information to the rule.

Dell’s proposal is that /ə/ turns into [ε] in closed syllables. However, French has a rule that creates closed syllables: schwa deletion. Schwa deletion could logically feed the CSA but it does not. In fact, the CSA must crucially apply before schwa-deletion: aʃəvəmã *[aʃvəmã] [aʃεvmã] achèvement ‘finalisation’ (Durand, 1986: 321). Since the process must apply before schwa deletion, the CSA would seem to occur in open syllables: /aʃəvəmã/ > aʃεvəmã > [aʃεvmã] achèvement ‘finalisation’ (Durand, 1986: 321). This is also the case for e-adjustment in forms that never have schwa deletion: [sεdəʁje] cèderiez ‘would leave’ (Durand, 1986: 321).

One option, to retain this as a phenomenon of the closed syllable is to introduce an arbitrary and temporary coda-capture condition stage in the derivation (Anderson, Reference Anderson1982). A token such as /proteʒəra/ would therefore undergo resyllabification/‘codafication’: pro.teʒ.ə.ra then undergo CSA, before then deleting the schwa and finally resyllabifying the captive coda as an onset: [pro.tε.ʒra] ‘will protect’. As Durand (1986: 321) points out, however, this derivation suffers from the entirely arbitrary coda-capture stage. In fact, Dell’s original rule avoids this precisely by not being just a phonological closed-syllable readjustment. It introduces a strange (and non-modular) condition to the rule.

The object ⌢C1 stands for the condition whereby the alternating vowel and the C must belong to the same morpheme (shown greyshaded): [aʃəvəmã] achèvement ‘finalisation’. This morphological condition could be seen as a way of artificially introducing the notion of a strong word-final position (that, by hypothesis, is stressed).

In addition to this, the claim that French does not allow schwa in closed syllables is suspect at best. In fact, pre-theoretically there are straight counterexamples to the claim: [ʁəs.tχyk.ty.ʁe] re + structurer ‘restructure’ & [ʁəvniʁ] re + venir ‘come again’ (Noske, Reference Noske, van der Hulst and Smith1982: 295).

This evidence has even been taken as evidence for prefixes not being part of the PWd of French (assumed to be stem+suffix) (Hannahs, Reference Hannahs1995: 34). However, this interpretation of the counterexample crucially requires one to accept: (a) the prosodic hierarchy (Nespor and Vogel, Reference Nespor and Vogel1986) and/or (b) that prefixes are not part of the PWd in French.

There are, however, reasons to think that proclitics in French are ‘internal (pro)clitics’ in the sense of Selkirk (Reference Selkirk, Morgan and Demuth1996) that is that they are “incorporated into the same PWd word as its host” (Anderson, Reference Anderson2005: 46). A number of factors give this impression. Firstly, in this context, there is voicing assimilation that we do not see across word-boundaries: /ʒ(ə) + pãns/ [ʃpãs] je pense ‘I think’ vs. [koʁiʒ pɔl] corrige Paul ‘correct Paul’.Footnote 16 Secondly, definite articles have also been taken to be internal clitics due to the fact that (a) they are subject to schwa deletion as they are PWd internally: /lə + bato/ [lbato] le bateau ‘the boat’, and (b) articles are syllabified as onsets of vowel-initial stems: /lə + o/ [lo] l’eau ‘the water’ (Tremblay and Demuth, Reference Tremblay and Demuth2007). Given that CSA is taken to be a word-level process, we should expect the schwa of procliticized definite articles to undergo CSA when they form closed syllables, but this is counter to the facts: /lə + ski/ [ləs.ki] *[lεs.ki] le ski ‘the ski (sport)’.Footnote 17

Going back to the CSA, a clever departure from the unmotivated consonant-capture approaches and the morphemic condition was proposed by Durand (Reference Durand1976; Reference Durand1980; 1986) and Selkirk (Reference Selkirk and Fretheim1978). This approach uses the metrical foot as the domain of application of the rule. However, given the examples such as /rə + vənir/ [ʁəvniʁ] revenir ‘come again’ mentioned above, the foot-analysis is obliged to have two types of feet: (a) Lexical and (b) Sentence (Durand, 1986: 325).

Durand’s account may indeed be correct and I think it is consistent with the simpler claims made in this article (it depends on how one views all the interconnected claims and predictions). However, in the account that I am presenting, based in locating stress in underlying forms (even if it is predictable), there would simply be no expectation of an [ə - ε] alternation in these exceptions to the ‘no schwa in closed syllables’ rule: /lə + ski/ [ləs.ki] *[lεs.ki] le ski ‘the ski (sport)’, /rə + vənir/ [ʁəvniʁ] revenir ‘come again’ and [ʁəs.tχyk.ty.ʁe] restructurer ‘restructure’ since none of them are stressed and, following Charette (Reference Charette1991), ə-adjustment is pegged to word-level stress.

For Standard French, theoretically and typologically, we would not expect to see fortition of a schwa in a final closed-syllable, unless it was stressed. So, echoing the conclusion of section 2, it seems more phonologically appropriate to assume that the strength in this position is conveyed by phonological stress rather than purely by its positionality.

4. Further arguments for final prominence in French

The root-final position in French is strong and this strength should be interpreted as stress-based rather than positional. I will present some phenomena where final strength is taken as stress, even if stress is not interpreted as accent (Vaissière and Michaud, 2016: 49).

4.1. Liaison mistakes L1

French children make many types of mistakes in their development of adult-like liaison (Grégoire, Reference Grégoire1947; Chevrot and Fayol, Reference Chevrot, Fayol, Almgren, Barrena, Ezeizabarrena, Idiazabal and MacWhinney2001; Dugua, Reference Dugua2006; Chevrot et al., Reference Chevrot, Dugua and Fayol2009; Wauquier, Reference Wauquier, Angoujard and Wauquier2003; 2015). Some common mistakes include the selection of the wrong consonant: *lenami, lack of liaison: *le.ami, and misalignment: *lez.ami (cf. [le.za.mí]) ‘the friends’. One error-type, shown in (14) is highly relevant to the discussion of word-stress in French because it applies to the word not the phrase.

The consonant that harmonizes is often the onset of the final syllable.Footnote 18

This raises the question of why the final syllable should be particularly ‘copy-able’. Locality conditions would ordinarily force copying of the closer consonant: [lelelefã] les éléphants ‘the elephant’. These forms, if attested would be immediately explicable due to locality, but the error-type [lefefefã] and [lefelefã] requires non-local special prominence of the final syllable to explain it.

Typologically, long distance harmony/ feature spreading is sensitive to stress in a number of ways (what is a trigger, what is a target, what bounds the spreading) (Hanson, 2001: 2000). Therefore, I would suggest, in light of the other arguments in sections (2) and (3), that this child-language consonant-harmony is caused by the phonological stress of the final syllable, rather than just its finality.

Undoubtedly, it is the strength of the final position that causes the harmony effect, however, the strength of this position is given by stress, rather than by being final since it is positionally weak.

4.2. Taboo-avoidance/Diminutive reduplication

Then there is CV reduplication. Morin (Reference Morin1972) called these forms ‘echo-words’, but I will refer to them as RED(CV)-forms to avoid possible confusion with salad-salad reduplication (Ghomeshi et al., Reference Ghomeshi, Jackendoff, Rosen and Russell2004).

This reduplication has a diminutive function, as well as lessening the intensity of taboo words. The taboo-avoidance function is retained in adult-directed language, while its diminutive function is found almost exclusively in child-directed speech.

It should also be stated that not all speakers produce all forms listed beneath, however, all speakers can obtain the intended meaning when presented with these reduplicated forms. I take this to show that it is part of the competence of native speakers.

Naturally, these are not the only ways to form cutesy, diminutivizing forms of words, the language also has other strategies such as the example furnished by a reviewer: pantalon pattes d’éléphant → pantalon pattes d’eph “bellbottoms”. In fact, for some items it may not even be the most frequent strategy, crocodile: crocro, croco, croc, but amongst these there is also: croc didile (personal profile name Facebook, accessed 11/04/2020). Other possibilities are unthinkable: crocodile → *co-co.

These multiple options exist just as a language can have many ways of forming hypocoristics (Alber, Reference Alber2010). However, I follow Morin (Reference Morin1972) in interpreting these as a distinct paradigm. I think all native speakers would agree that the starred forms do not fit in this paradigm: such as (15c): [fã-fã] *[le-le] éléphant ‘elephant’.

As shown in (15ai), the reduplication applies to monosyllabic stems producing CV-CV forms: [ne-ne] ne ‘nose’. The process also reduplicates the initial CV of CVC stems (15aii): [bi-bít] bitte ‘penis’, [te-tέt] tête ‘head’. This shows that this strategy really is CV reduplication, rather than syllable reduplication.

The fact that the loi de position applies to the output of RED(CV): [fe-fέs] *[fε-fέs] fesses ‘buttocks’ strongly suggests that these forms come from a word-building operation applied to UR inputs. Then the constructed form is fed to the regular word-level phonology of the language.

The forms in (15b-c) show that only the final (stressed) syllable is reduplicated. In constructing these forms, shortenings or truncations based on any other syllable of the word are ‘inconceivable’ to native speakers: [fã-fã] *[le-le] éléphant ‘elephant’. Importantly, *[le-le] is not excluded as the RED(CV)-form of ‘elephant’ because it is somehow sub-minimal (cf. [ne-ne] ne ‘nose’).

The crucial aspect of this process as it applies to “word”-stress is that the reduplication is unambiguously word-based: le [pε̃-pε̃] vert vs. *le [ve-lapε̃-vέʁ] ‘the green rabbit’.

This pattern suggests that the final syllable is strong in French, this is not inherent positional strength, I claim it is phonological stress.

RED(CV)-reduplication in French can be analysed as: ‘reduplicate the first stressed CV of the word’, reminiscent of hypocoristic strategies (Alber, Reference Alber2010). Indeed, from a typological perspective, this kind of truncation behaves very much like stress in the hypocoristic formation of other Romance languages.

Hypocoristic formation is typically stress sensitive. Typically, it involves selecting, reduplicating or truncating up to the stressed syllable (see (16a)). Or it targets the initial position (even if unstressed): [ɹiː.ɹi] from [ɹijánə] ‘Rhianna’ (see also 16a), thereby confirming its inherent strength.

The targeting of unstressed syllables both medial and final is unattested in systematic productive hypocoristic formation that produces paradigms in the language. Examples involving unstressed medial and final syllables are all sporadic examples: Eng.: burbs ‘suburbs’, rents ‘parents’, Beth ‘Elizabeth’, Hung. Nika from [véronika], Ita. Beppe & Peppe, Peppino from ‘Giuseppe’ and perhaps most strikingly: Northern Peninsular Spanish: Jóse María > jó se ma rí a > sema > chema), though the segmental changes accompanied with it show it is highly sporadic.Footnote 22 In European Portuguese, Lurdes Ferreira (p.c.) reports that out of her corpus of 600 hypocoristics there is a solitary example of a final unstressed syllable form: Catarina > na. All other monosyllabic hypocoristics are formed from the stress syllable: José > Zé. From this same corpus, Ferreira reports that 76.5% of forms preserve the stressed syllable of the original, and when they do not the rest preserve the initial syllable: Diána > Di. Accordingly, I propose the following as a sketch-derivation of the RED(CV) paradigm.

In all of these forms, reduplication cannot wait for stress to be applied phrasally in order to apply; by then it would be too late (it would apply counter-cyclically): le [pε̃-pε̃] vert, *le [ve-lapε̃-vέʁ] ‘the green rabbit’. This has to imply sub-phrasal strength in French, most likely due to stress (given the typological considerations).

5. Conclusion

French word-final syllables are strong but this is not the result of positional strength, rather it is the prosodic strength of a phonologically stressed syllable. The implication is that stress is an underlying property of roots in French. However, since it is a purely syntagmatic relation, it does not generate minimal pairs. These findings suggest that syntagmatic evidence of prominence is enough to affect underlying forms without the need for contrastivity and minimal pairs. It is undisputed that the lexicon should contain all of a lexical item’s unpredictable information, but it is far from established that the lexicon should contain only a lexical item’s unpredictable/contrastive information (pace Dresher, 2009).Footnote 23 A structurally similar argument is made for Abkhaz where non-contrastive information is nonetheless shown to be present in abstract phonological underlying forms leading to considerable lexical redundancy (Vaux and Samuels, Reference Vaux, Samuels, Brentari and Lee2018).

This article makes no claim as to the way that this phonological stress is represented (whether there are feet or not (Durand, Reference Durand1976; Reference Durand1980; 1986; Selkirk, Reference Selkirk and Fretheim1978; Charette, Reference Charette1991; Eychenne, Reference Eychenne2006; Goad and Buckley, Reference Goad and Buckley2006; Durand and Eychenne, Reference Durand and Eychenne2007), and neither does it conflict with the findings of many recently influential studies that highlight the phrase as a domain of phonetic accent in French (Delattre, Reference Delattre1966; Rossi, Reference Rossi1980; Vaissière, Reference Vaissière, Cutler and Ladd1983; Dell, Reference Dell, Dell, Hirst and Vergnaud1984; Martin, Reference Martin1987; Féry, Reference Féry and Sternefeld2001; Jun and Fougeron, Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000; Hyman, Reference Hyman and van der Hulst2014), these do not negate or conflict with analyses of phonological word stress (Vaissière and Michaud, 2016: 49).

Conversely, the experimental findings of French ‘stress deafness’ (Dupoux et al., Reference Dupoux, Pallier, Sabastian-Galles and Mehler1997, Peperkamp and Dupoux, Reference Peperkamp, Dupoux, Gussenhoven and Warner2002) might look like they are incompatible with finding stress beneath the phrase. But this is not so, my conclusions are fully compatible with the ‘stress deafness’ findings, except that one has to limit the explanation to the absence of contrastive stress, not the absence of underlying phonological syntagmatic strength distributions. As a reviewer points out, it is not clear that (Dupoux et al., Reference Dupoux, Pallier, Sabastian-Galles and Mehler1997; Peperkamp and Dupoux, Reference Peperkamp, Dupoux, Gussenhoven and Warner2002) exclude this possibility. At the very least there is agreement that French speakers are ‘stress deaf’ because stress is not paradigmatically contrastive.