Regarding campaigning in the twenty-first century, social media (especially Twitter) cannot be ignored. At the beginning of 2016, 44% of US adults reported that they had learned about the presidential election in the last week from social media, more than from any other media source (Gottfried et al. Reference Gottfried, Barthel, Shearer and Mitchell2016). In August 2017, the percentage increased: 67% of Americans reported that they get some of their news on social media (Shearer and Gottfried Reference Shearer and Gottfried2017). On Twitter, specifically, 74% of users report getting news from the site, an increase of 15 percentage points from the previous year (Shearer and Gottfried Reference Shearer and Gottfried2017).

While the percentage of adults turning to Twitter and other social networks for news has increased in recent years, there also has been growth in the adoption of social media by politicians. In 2011, only 44% of US senators were on Twitter; however, by 2013, 100% had adopted an account (Toor Reference Toor2013). Since then, there has been an explosion of research in the area of Twitter and elections (Jungherr Reference Jungherr2016).

There was hope in the beginning that the growth of social media for news would level the playing field for political candidates who lack the resources of incumbents. Twitter essentially is free (i.e., there is no membership fee or cost to use it) and a user can tweet as often as the mood inspires. Many hoped that especially third-party candidates would benefit from the platform because even those without financial resources can create and use these accounts (Gibson and McCallister 2009; Price Reference Price2012). Work in this area, however, suggests that there is a relationship between campaign funding and using Twitter (Ammann Reference Ammann2010; Evans and Sipole Reference Evans, Sipole and Richardson2017). Although tweeting is free, it takes time to draft and send tweets; therefore, those who have the monetary resources to hire staff to tend to their Twitter accounts are more likely to tweet (Ammann Reference Ammann2010; Evans, Cordova, and Sipole Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014). Using social media also exacerbates the gaps in monetary resources that already exist between major- and minor-party candidates (Hong Reference Hong2013).

Early work on third-party candidates and their propensity to tweet, however, suggests that this might not always hold true. Evans, Cordova, and Sipole (Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014) showed that although third-party candidates were less likely to have accounts during the 2012 US House elections, if they did have an account, they were more likely than their major-party colleagues to use it. Even when campaign spending was controlled, third-party candidates were still more active on Twitter than major-party candidates (Evans and Sipole Reference Evans, Sipole and Richardson2017).

There is limited scholarship that examines the way that third-party candidates use Twitter, and the work that exists examines only a single election or a single chamber. To see whether the playing field is evening out on Twitter between third-party and major-party candidates, this article uses data collected across three elections and within two chambers. The following discussion reexamines the original 2012 data from Evans, Cordova, and Sipole (Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014) and adds all of the tweets sent by all candidates for both the US House and the US Senate in 2014 and 2016. Although we demonstrate that there is still an adoption gap between third-party and major-party candidates, the former continue to have a different way of communicating with their followers on Twitter. Third-party candidates tweet more personal and less professional statements than major-party candidates.

To see whether the playing field is evening out on Twitter between third-party and major-party candidates, this article uses data collected across three elections and within two chambers.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Regarding the way that candidates campaign, many scholars have argued that the party that controls the majority can provoke those not in the majority to campaign in innovative ways, including using new media (Appleton and Ward Reference Appleton and Ward1997; Lowi Reference Lowi1963; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). Twitter offers many advantages to the out party. First, Twitter essentially is free. For candidates who lack the monetary resources to hire a professional staff, this is a benefit. Second, Twitter provides an outlet that bypasses the traditional media gatekeepers. If something happens in the world, users can go to Twitter to immediately respond or state their opinions on the matter instead of waiting to be invited on political-news programs. Because we now exist in the world of the shrinking sound bite and third-party candidates suffer in terms of their coverage in traditional news programming, tweets are “becoming the new ‘sound bite,’ allowing candidates to control more of the coverage of their public images and their campaigns” (Johnson Reference Johnson2012, 55). Twitter provides unlimited space for users to express their thoughts. Some authors have found that social media generally levels the playing field in terms of candidate mentions (Metzgar and Maruggi 2009).

Furthermore, it is impossible to discuss elections these days and not mention social media. Various authors have found that what candidates do on social media can affect their likelihood of winning and that Twitter can be analyzed to predict election outcomes (Tumasajan et al. 2011). Scholars found that citizens are greatly affected by what they see on Twitter, and politicians can mobilize followers and increase their fundraising by sending tweets (Hong Reference Hong2013; Park Reference Park2013).

Since tweeting can matter for political engagement and is helpful for out-party candidates, are third-party candidates using this platform in the United States? There are limited studies that examine third parties and Twitter behavior (Christensen Reference Christensen2013; Conway, Kenski, and Wang Reference Conway, Kenski and Wang2013; Evans Reference Evans, Davis, Holtz-Bacha and Marion2017; Evans, Cordova, and Sipole Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014; Evans and Sipole Reference Evans, Sipole and Richardson2017; LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht Reference LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht2013). Some of the existing work explores the way that presidential candidates tweet (Christensen Reference Christensen2013; Conway, Kenski, and Wang Reference Conway, Kenski and Wang2013; Jackson Reference Jackson2016). However, given the limited number of cases in those studies, there is little to extrapolate regarding the way that third-party candidates tweet in general. For congressional elections, in their study involving the 2010 US House election, LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht (Reference LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht2013) provided an initial look at whether third-party candidates were as likely to adopt a Twitter account. They found that third-party candidates were significantly less likely to have a Twitter account (i.e., 20.3% compared to 66% of Democrats and 79% of Republicans).

Haber (Reference Haber2011) also explored the Twitter behavior of candidates for the US Senate in the 2010 election. Although Haber examined only the Twitter behavior of viable third-party candidates, he found that Republicans and third-party candidates tweeted more often than Democrats in 2010.

Evans, Cordova, and Sipole (Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014) examined both the adoption and use of Twitter for all candidates running for the 2012 US House elections. Content analyzing every tweet sent from each candidate, they showed that whereas third-party candidates were again less likely to have accounts, those who had accounts used them more aggressively. Third-party candidates tweeted more often and sent more personal (i.e., non-campaign) tweets than major-party candidates. Third-party candidates also were more likely to send tweets about political issues than major-party candidates. These results were confirmed by a second study by Evans and Sipole (Reference Evans, Sipole and Richardson2017). Even after controlling for campaign finance, third-party candidates sent more issue-specific and personal tweets than major-party candidates.

Further work by Evans regarding the 2014 US House elections showed that third-party candidates were less likely to send tweets about civic engagement. Third-party candidates sent fewer tweets about voting, registration, volunteering, and joining a political cause (Evans Reference Evans, Davis, Holtz-Bacha and Marion2017). These findings hold as well for Senate candidates in 2014.

Reviewing other online media, there is not much work involving third parties. What exists suggests that there also is a gap between third-party and major-party candidates on websites, but the gap may be shrinking. Gulati and Williams (Reference Gulati and Williams2007) showed that there was a significant increase in website presence of third-party US Senate candidates between 2004 and 2006. There was, however, a decent gap that still existed between major-party and third-party candidates in the US House elections. For both chambers, major-party candidates were more likely to include a biography and news on their websites; however, as they described, this might be because third-party candidates were less likely to hold events. Third-party candidates were as likely to express their issue positions on their websites, but major-party candidates were twice as likely to post audio and video. Similar to the Evans and Sipole (Reference Evans, Sipole and Richardson2017) findings described previously, in the US Senate elections, major-party candidates also were more likely to have online volunteer sign-ups and to provide information on where and how to vote.

To summarize, there is little work on which to draw any formidable conclusions regarding how third-party candidates use Twitter. It seems that third-party candidates are less likely to have an online presence (i.e., whether a website or a Twitter account), and they spend their time discussing different topics than major-party candidates, perhaps to the detriment of their campaign. The following discussion explores how third-party candidates have used Twitter during the past three elections.

It seems that third-party candidates are less likely to have an online presence (i.e., whether a website or a Twitter account), and they spend their time discussing different topics than major-party candidates, perhaps to the detriment of their campaign.

METHODS

To determine the effect of partisanship on the way candidates use Twitter, we collected and hand-coded tweets sent from every candidate running for the US House in 2012, 2014, and 2016 and for the US Senate in 2014 and 2016. In all, this resulted in a dataset of 3,456 candidates across those three years for the US House and 309 candidates for the US Senate.Footnote 1 The first step was to locate the Twitter accounts for all candidates running for the US House and US Senate. As in previous research, we then hand-collected or downloaded the final two months of their Twitter history before each election (Evans and Clark 2016; Evans, Cordova, and Sipole Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014; Gainous and Wagner Reference Gainous and Wagner2014). This allowed us to examine all campaigns after the end of the primary season, producing a dataset of 230,907 total tweets for the US House and 54,604 total tweets for the US Senate across those three elections.Footnote 2

After we collected the tweets for these years, we then hand-coded them for content. Following Evans, Cordova, and Sipole (Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014), we coded the tweets using the following categoriesFootnote 3:

• Campaign: These were tweets in which candidates talked about where they had been during the campaign and with whom they had been meeting. These tweets also included those in which candidates linked videos that their campaign had made or linked to their websites for information about their candidacy.

• Media: These tweets were those in which candidates encouraged followers to either watch a program they would be on or linked a newspaper article written about them.

• Position Taking/Policy Statement (Issues): These tweets were meant to bring awareness to a public-policy area. If a candidate tweeted something about an issue but did not take a side on it (e.g., “Here’s an article about the Dream Act”), the tweet was coded as a policy statement. If a candidate took a side on the issue (e.g., “I fully support the implementation of the Dream Act”), the tweet was coded as position taking.Footnote 4

• Attack: These tweets were those in which candidates made unflattering statements about their opponents.

• Attack Other: These tweets were those featuring negative statements about the Democratic Party, Republican Party, government, current president, or other group (e.g., the media).

• Personal: These were the tweets that did not fit in any of the previous categories—for example, those in which a candidate wished someone a happy birthday.

The intercoder reliability was calculated for each sample across the three periods. The coders in each sample achieved a minimum 90% agreement.

In the following results, we divided our sample by party identification. All independent and third-party candidates were grouped together, whereas Republicans and Democrats were analyzed separately.Footnote 5 Party identification was gathered from Ballotpedia.

All candidates were examined for their adoption of a Twitter account, and only those with accounts were compared for their use of the social-network site. In 2012, only original tweets were analyzed. In 2014, original and retweets were included. In 2016, only original tweets were included.

Given the similarity of findings for both the US House and the US Senate during these election years, only the former results are presented. US Senate results are available in the online appendix and the overall findings are discussed in the conclusion.

RESULTS: 2012

In 2012, third-party candidates in the US House were significantly less likely to have Twitter accounts. Only 25.2% of third-party candidates had accounts, whereas 84.8% of Republicans and 81.1% of Democrats had accounts.

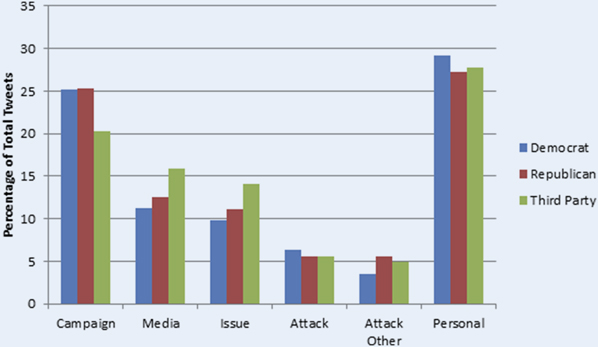

In terms of use, Republicans and Democrats acted similarly in their use of the platform (figure 1). Democrats tweeted, on average, 84 times, whereas Republicans tweeted 81 times during the final two months of the campaign. The content of their tweets also was similar: both used campaign tweets, media tweets, personal tweets, and issue-specific tweets at an equal rate. Democrats were slightly more likely to use attack and user-interaction tweets, whereas Republicans were more likely to use attack Democrat tweets. However, the differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 1 2012 US House Twitter Style

Third-party candidates, conversely, were using Twitter in a completely different way. Although most third-party candidates did not have accounts, those who used the social-network site were more aggressive. They tweeted, on average, 136 times during the final two months of the campaign. However, that average includes one third-party candidate (i.e., Steve Carlson, Minnesota District 4) who tweeted significantly more than the other candidates (i.e., 1,133 tweets). When Carlson is omitted from the analysis, third-party candidates sent, on average, 121 tweets—which is still significantly more than the Republican and Democratic candidates’ average.Footnote 6 Third-party candidates also were more likely to discuss their appearances in the media and bring up issues in their tweets; they were less likely to send traditional “campaign”-related tweets.Footnote 7

FINDINGS: 2014

In the US House in 2014, there were 1,125 candidates, 306 of whom were third-party candidates (27.2%). Third-party candidates in 2014 also were less likely to have a Twitter account. Only 121 of those candidates were tweeting during the race (39.5%), which is a significant increase from the previous year (25.2%). For comparison, 88% of Democrats and 89% of Republicans had Twitter accounts.

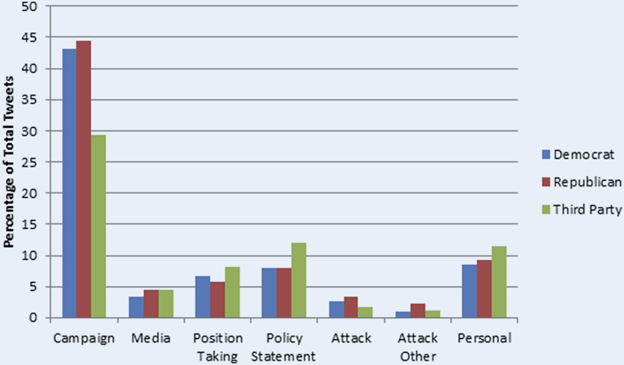

In the final two months of the 2014 US House races, the number of tweets sent from these respective parties was about equal, with both Republicans and third-party candidates sending approximately 135 tweets each, on average, and Democrats sending 148.Footnote 8 When we examined the content of their tweets, we found that third-party candidates were tweeting similarly to major-party candidates, except in one area. Minor-party candidates were significantly less likely to use campaign tweets than major-party candidates (figure 2).Footnote 9 Although they sent more policy-statement, position-taking, and personal tweets than major-party candidates, those differences were not significant. However, they seemed to be more focused on issues on Twitter than major-party candidates.

Figure 2 2014 US House Twitter Style

FINDINGS: 2016

During the 2016 US House races, there were 1,212 candidates but only 774 of them used Twitter. The average number of original tweets sent during the final two months of the race was 57.45. When we examined adoption and tweeting by partisanship, we found—as in previous years— that third-party candidates were less likely to have accounts. Of the 258 third-party candidates running in the 2016 US House races, only 63 had accounts (24.4%) compared to 70.8% of Republican and 79% of Democratic candidates. The percentage of third-party candidates that had accounts is similar to the 2012 findings.

Third-party candidates also sent fewer tweets than major-party candidates in 2016 but not significantly fewer. On average, third-party candidates sent 49.8 tweets during the final two months of the election, whereas Republicans sent 54 and Democrats sent 61.8.

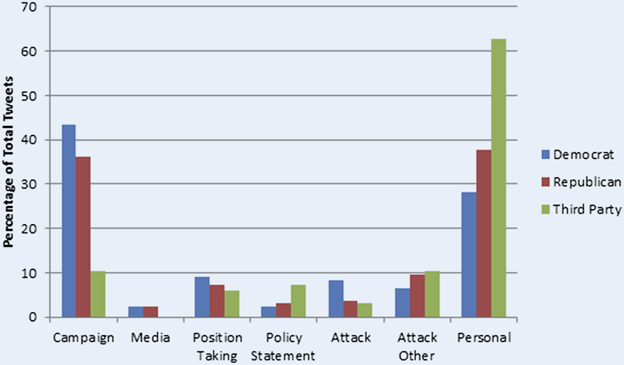

The content of the tweets from major-party and third-party candidates was different in ways similar to 2012 and 2014. As in both earlier elections, third-party candidates were less likely to tweet about their campaigns than major-party candidates. They also sent significantly more personal tweets.Footnote 10 More than 60% of third-party candidate tweets were unrelated to their campaigns, whereas only 28% of Democratic and 37% of Republican candidate tweets followed suit. Democrats also sent more attack tweets than Republicans and third-party candidates (figure 3). Third-party candidates sent no media tweets during the election but sent proportionately more policy-statement tweets than the major-party candidates, which also is similar to the earlier elections.

More than 60% of third-party candidate tweets were unrelated to their campaigns, whereas only 28% of Democratic and 37% of Republican candidate tweets followed suit.

Figure 3 2016 US House Twitter Style

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our results indicate that third-party candidates do not use Twitter similarly to major-party candidates. Third-party candidates are significantly less likely to have Twitter accounts. Although there has been a minor increase in Twitter adoption since the early results of LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht (Reference LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht2013), there still exists a large gap between third parties and major parties in terms of their Twitter adoption, which may affect election results.

Third-party candidates sent more tweets than major-party candidates during the 2012 US House races but had a number of tweets comparable to major-party candidates in the 2014 and 2016 races. In the US Senate races, third-party candidates sent significantly fewer tweets than major-party candidates across both years (see the online appendix). The average number of tweets sent by major-party candidates across these years did not change significantly.

When we reviewed the content of the tweets, across all three years, third-party candidates tweeted more about issues than major-party candidates. As the realignment literature suggests, during times of third-party strength, particular issues are not addressed adequately by the two major parties (Rosenstone, Behr, and Lazarus Reference Rosenstone, Behr and Lazarus1984). This may explain why third-party candidates are spending more time discussing issues. Because they obviously feel left out of politics, these candidates spend more time talking about issues for which they care deeply. During the 2014 election, for instance, we found that third-party candidates who were excluded from the debates in their districts and states were likely to live-tweet their responses to questions asked at the debates—which many times resulted in tweets about issues. The major-party candidates, conversely, were not sending those types of tweets because their answers were being broadcast on traditional media.

Third-party candidates also were more likely to tweet about personal issues and less likely to send traditional “campaign” tweets. Similar to the work by Gulati and Williams (Reference Gulati and Williams2007) involving campaign websites, we believe that these differences may be attributed to the sheer number of campaign events that third-party candidates have relative to major-party candidates. Perhaps they tweet less about their campaign because there are not as many events to discuss and campaign ads to share.

By not using Twitter, third-party candidates are missing approximately one fourth of US adults who are using Twitter (Greenwood, Perrin, and Duggan Reference Greenwood, Perrin and Duggan2016), especially younger adults, who are already more likely to adopt positions that are in line with third-party candidates (Hindman and Tamas 2016). Research shows that third-party candidates get little traction in traditional media coverage (Hindman and Tamas 2016; Morse Reference Morse2016); therefore, using Twitter would allow them to bypass the traditional media gatekeepers. Other research found that winners of elections send more messages and spend more time on mobilization of their followers on Twitter (Evans, Ovalle, and Green Reference Evans, Ovalle and Green2016). Therefore, third-party candidates should reevaluate how they spend their time on Twitter.

Furthermore, Hong (Reference Hong2013) showed that social media use results in increased donations from outside donors. Given how limited campaign funding is for third-party candidates, they should think more seriously about adopting and using Twitter. Hong’s (2013) research also found that politicians who have more extreme ideologies benefit the most from adopting social media, which means that third-party candidates should benefit the most from using Twitter. For all of these reasons, third-party candidates should consider using Twitter in their campaigns. Instead of discussing personal issues on Twitter, third-party candidates should explore ways to increase their campaign funding using this social network.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518001087