Introduction

Wildlife agencies have documented the negative impacts of poaching on wildlife, but rarely attempted to quantify the threat that the international wildlife trade poses to people (WWF/Dalberg, 2012). Some studies have documented links between the illegal wildlife trade and violence, organized crime and human trafficking (WWF/Dalberg, 2012; Brashares et al., Reference Brashares, Abrahms, Fiorella, Golden, Hojnowski and Marsh2014; Douglas & Alie, Reference Douglas and Alie2014). However, community perceptions of wildlife poaching can vary as a result of factors that include the underlying motivation for poaching (e.g. subsistence, commercial, perceived injustice; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Roe, Baker, Travers, Plumptre and Rwetsiba2015), cultural traditions, economic status, and the relationships between poachers and the communities affected by poaching (McCay, Reference McCay1984; Kuriyan, Reference Kuriyan2002; Rippl, Reference Rippl2002; Hampshire et al., Reference Hampshire, Bell, Wallace and Stepukonis2004). Regardless of these perceptions, poaching poses a risk to both people and wildlife.

Biodiversity is generally richest in rural areas, particularly in developing nations (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000), and these areas are often poaching hotspots. Rural communities frequently experience poverty and food insecurity, and have more limited access to education and health care compared to their urban counterparts. Wildlife conservation policy and management often affect marginalized rural communities by reducing their access to natural resources, which can lead to negative attitudes towards conservation (Woodroffe et al., Reference Woodroffe, Thirgood and Rabinowitz2005; Mwangi et al., Reference Mwangi, Akinyi, Maloba, Ngotho, Kagira, Ndeereh and Kivai2016) and jeopardize human–wildlife coexistence (Parry & Campbell, Reference Parry and Campbell1992; Woodroffe et al., Reference Woodroffe, Thirgood and Rabinowitz2005). In contrast, people living in urban areas are often unaware of the difficulties that rural communities face, including reduced access to resources, intimidation by poachers and threats posed by wildlife. Consequently, urban and rural communities may have opposing experiences with, perceptions of, and attitudes towards poaching, illegal wildlife trade and conflict involving wildlife (Bandara & Tisdell, Reference Bandara and Tisdell2003).

Poaching can increase if local communities suffer from negative interactions with wildlife (Mehta & Kellert, Reference Mehta and Kellert1998; Kansky & Knight, Reference Kansky and Knight2014) or perceive restrictions imposed by conservation policies as unfair (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Roe, Baker, Travers, Plumptre and Rwetsiba2015). In such circumstances, communities may poach in retaliation against the species that are the focus of such policies (Kissui, Reference Kissui2008; Gore et al., Reference Gore, Ratsimbazafy and Lute2013) or as a means to decrease or prevent future conflict involving wildlife (Sánchez-Mercado et al., Reference Sánchez-Mercado, Ferrer-Paris, Yerena, García-Rangel and Rodríguez-Clark2008). In contrast, people living in urban areas rarely experience negative interactions with wildlife, but instead may enjoy the benefits associated with conservation (e.g. improved income from tourism; Holechek & Valdez, Reference Holechek and Valdez2018). In addition, urbanites are more likely to hold idealized views of charismatic species such as elephants (Bandara & Tisdell, Reference Bandara and Tisdell2003), and may not be fully aware of the complexities around poaching, conservation and human–wildlife coexistence.

Attitudes, beliefs and norms drive the way individuals think about and behave towards wildlife (Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Manfredo and Lipscomb1996; Whittaker et al., Reference Whittaker, Vaske and Manfredo2006). Determining the attitudes of local communities towards wildlife can help agencies to create effective conservation strategies that align with stakeholder priorities. Similarly, understanding local norms can inform whether agencies can expect people to abide by wildlife protection laws or engage in poaching activities (St. John et al., Reference St. John, Mai and Pei2015).

Myanmar is a critical area for the conservation of the Asian elephant Elephas maximus (Leimgruber et al., Reference Leimgruber, Gagnon, Wemmer, Kelly, Songer and Selig2003), but levels of poaching in the country are high (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, McEvoy, Oo, Chit, Chan and Tonkyn2018). To improve elephant conservation in Myanmar, we sought to: (1) assess attitudes and perceptions of urban and rural communities regarding Myanmar's elephant populations, (2) assess their experience with, attitudes towards and perceptions of poaching activities and products derived from poached elephants, (3) determine their willingness and motivations for complying with elephant conservation laws, and (4) identify the impacts of elephant poaching experienced by community members.

Study area

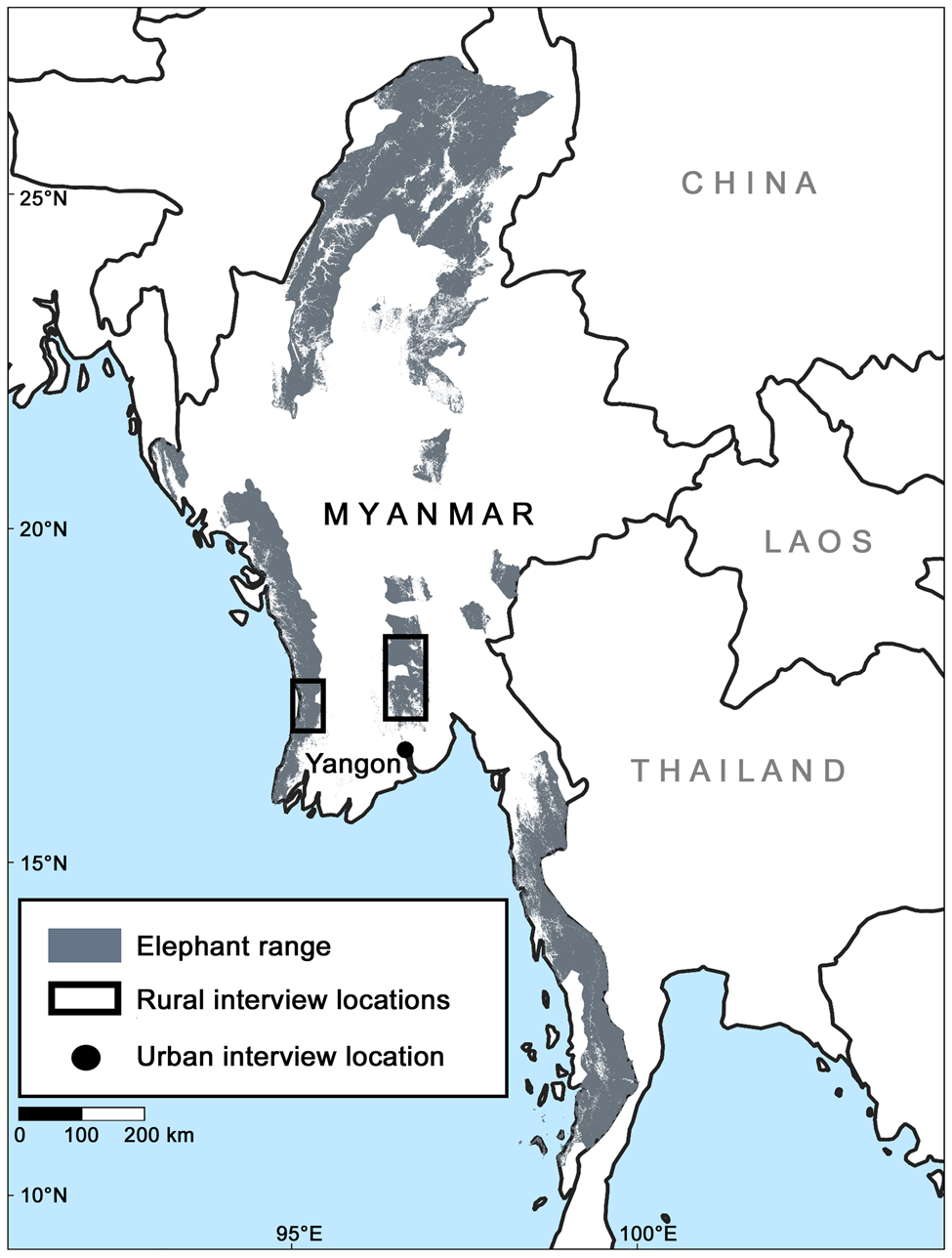

To assess the views of people living near elephants in rural areas and those in urban areas without elephants, we interviewed communities across central and western Myanmar during December 2016–May 2018 (Fig. 1). We interviewed people in easily accessible villages in two rural areas: 20 villages in the Ayeyarwady Delta region and 11 villages in the foothills of the southern Bago Yoma mountain range. All urban interviews were conducted in Yangon, the former capital of Myanmar.

Fig. 1 Locations of interview surveys on elephants and elephant poaching in rural and urban locations in Myanmar (December 2016–May 2018).

Methods

Questionnaire

Our questionnaire consisted of 34 items in four sections (Table 1). The first section covered demographical characteristics of participants. The second investigated their attitudes towards elephants and perceptions of the costs and benefits of living with them. The third part asked participants about their knowledge of elephants, and their motivation to comply with conservation laws. The final section explored the participants' experiences and perceptions of hunting and poaching. An ‘I do not know’ response option was provided for all questions and was treated as a non-response in the analyses.

Table 1 Summary of the questions included in our study of views and perceptions of elephant poaching in rural and urban communities in Myanmar (December 2016–May 2018).

1 MC, multiple choice; Open, open ended; Likert, 5-point Likert statement, with 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral and 5 = strongly agree; T/F, true or false; Y/N, yes or no.

We administered the questionnaire orally in the Myanmar language (Supplementary Material Appendix 1). Interviews lasted c. 30 minutes, and were conducted by CS and 12 field crew members from local conservation organizations and academic institutions who had participated in a training session covering the approved interview protocol and data recording methods.

Participant recruitment

We used a mixed method approach for recruiting participants. In villages, we implemented a stratified random sampling framework. The interviewer approached the first house they saw to request an interview. If no adults were present in the home, or residents did not wish to participate in the study, the interviewer moved on to the nearest house and every subsequent house until they found a willing participant. Once the interviewer had completed a survey, they skipped the nearest two houses and approached the third home for participation. In addition to the household sampling, we employed a convenience sampling approach to recruit participants in communal areas in villages (e.g. tea shop, bus stop). The interviewer approached the first potential participant they saw upon arrival at the location. Once the interview was completed, the interviewer allowed three people to pass before approaching the next potential participant.

For the urban sample, we used the convenience sampling approach to recruit participants in Yangon in five public locations: Mingalar market, People's Park, Sule Pagoda, Kandawgyi Park and Sule Park. We also conducted interviews in two nature-themed urban locations, Yangon Zoo and Hlawga National Park. We found no difference in responses between public and nature-themed locations for all but one question (Supplementary Material 2), and therefore combined responses into a single dataset for urban areas.

Data analysis

We determined data distribution to be non-normal, using the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro & Wilk, Reference Shapiro and Wilk1965). We used the non-parametric unpaired two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Hollander et al., Reference Hollander, Wolfe and Chicken1973) to test for significant (α = 0.05) differences of the Likert scale responses between participants from urban and rural locations. We used χ 2 tests to test for significance (α = 0.05) for all other question types. We determined effect size using Cohen's d (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Statistical analyses were conducted in R 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2013).

Results

We conducted a total of 178 interviews, 83 in rural and 95 in urban locations. The mean age was was 41 ± SE 1.5 and 28 ± SE 1 years old for rural and urban participants, respectively. Rural interviewees were primarily men (67 men, 15 women), whereas the numbers of men and women in the urban sample were nearly equal (46 and 44, respectively). Gender was not reported for one rural participant and five urban participants. The majority of the participants self-identified as Burmese in both rural (71%) and urban (69%) locations, and the remaining participants as Rakhine, Mon, Kayin, Chin or other. Most participants were Buddhist (92% rural and 88% urban, respectively), with the remainder following Christian, Hindu, Muslim or other religions.

Attitudes towards elephants

Overall, both rural and urban participants had positive attitudes towards elephants. Both groups displayed a similar level of belief that elephants should be protected because of the benefits they provide to people (Supplementary Material 3). Enjoyment from seeing elephants was the benefit most reported by rural participants (81%, n = 78), followed by job creation in the tourism and conservation industries. Urban participants reported that income from tourists coming to Myanmar to see elephants was the most common benefit they received (77%, n = 74), followed by the labour elephants provide (73%, n = 70).

Rural participants were significantly more likely to agree that elephants were an important part of religion in Myanmar (P < 0.01; Fig. 2), but less likely to believe it is possible to coexist with them (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). Rural participants were also less likely to believe it is possible to share the same land with elephants (P < 0.001; Fig. 2) or that it is acceptable for elephants to be used in the tourism (P < 0.01; Fig. 3) and timber industries (P < 0.001; Fig. 3). Rural respondents were more likely to prioritize the needs of humans over the needs of the wild elephant population than urban participants (P < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Attitudes of rural and urban participants in Myanmar towards elephants on a 5-point Likert scale (December 2016–May 2018). Asterisks denote significant differences between urban and rural respondents: ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Fig. 3 Perceptions of rural and urban participants in Myanmar of the costs and benefits of living with elephants on a 5-point Likert scale (December 2016–May 2018). Asterisks denote significant differences between urban and rural respondents: ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Knowledge about elephants and conservation

We found no significant difference between rural and urban participants in knowledge about the conservation status of Asian elephants in Myanmar. The majority of both rural (97%; n = 79) and urban (89%; n = 73) participants correctly identified that elephants were an Endangered species that was legally protected, and that out of all countries with Asian elephants Myanmar had the largest extent of remaining elephant habitat (rural = 90%, n = 58; urban = 81%, n = 64; Supplementary Material 4). When asked about their perceptions of changes to the status of Myanmar's elephant population over the past 5 years, 58% (n = 83) of rural and 38% (n = 95) of urban participants believed the elephant population had decreased. Both groups pointed to poaching as the greatest threat to wild elephants (rural = 67%, n = 79; urban = 57%, n = 81; Supplementary Material 5), followed by habitat degradation (rural = 24%, n = 79; urban = 37%, n = 81).

Urban participants were significantly more likely than rural participants to state they were familiar with the country's wildlife laws (P = 0.03; Fig. 4) and believed they had a moral obligation to comply with elephant protection regulations (P < 0.001; Fig. 4). Both groups showed strong motivation for complying with laws that protect elephants (Fig. 4). Seventy per cent of rural (n = 80) and 92% of urban (n = 87) participants agreed that wildlife poachers should be punished for their actions, and > 90% of both rural and urban participants believed that elephant poachers are likely to be captured by authorities.

Fig. 4 Motivations of rural and urban participants in Myanmar to comply with wildlife laws (December 2016–May 2018). Asterisks denote significant differences between urban and rural respondents: * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001.

Most rural (70%, n = 79) and fewer urban (28%, n = 78) participants reported being afraid of poachers (Table 2), for reasons including that poachers are ‘bad’ and ‘aggressive’, ‘bring guns and violence’, and ‘they can kill me’. Most rural participants (76%, n = 26) indicated that elephant poachers were native to Myanmar, whereas most urban participants (85%, n = 53) assumed that poachers came from both Myanmar and other countries. Both groups thought that the primary reason for poaching was for monetary gain (n = 58). When asked which parts of the elephant were taken by poachers, rural participants most commonly indicated tusks (64%, n = 83; Supplementary Material 6) and skin (39%), whereas urban participants mentioned tusks (69%, n = 95), skin (18%), or stated they did not know or did not answer the question (18%).

Table 2 Summary statistics of yes/no responses and number of rural and urban participants who responded to the questions about their experiences with poaching in Myanmar (December 2016–May 2018).

Discussion

Attitudes towards elephants

Although both groups of participants overall had a positive view of elephants, there was a distinction in rural and urban attitudes towards elephants. Rural communities commonly see elephants as pests (De Boer & Baquete, Reference De Boer and Baquete1998; Tisdell & Xiang, Reference Tisdell and Xiang1998), which may explain why rural participants rejected the possibility of human–elephant coexistence and were less supportive of protecting elephant habitat. Similarly, the threat of negative interactions with elephants may lead rural communities to deny the species' ecological importance and undermine their support for elephant conservation. However, rural residents perceived that elephants had a significantly greater importance in religion than did urban residents, although a majority of all participants self-identified as Buddhists.

Costs and benefits of living with elephants

Effective elephant conservation may result in increased wild populations and consequently greater challenges with respect to coexistence with people. Despite this, both urban and rural respondents felt that conserving elephants was not a waste of resources. Elephants can cause significant damage to crops and sometimes livestock (Fernando et al., Reference Fernando, Wikramanayake, Weerakoon, Jayasinghe, Gunawardene and Janaka2005; Rodriguez & Sampson, Reference Rodriguez and Sampson2019), which affects rural communities more directly than people in urban areas. Increasing negative interactions as a result of conservation actions (Redpath et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams and Sutherland2013) could result in rural participants being more inclined to prioritize the needs of people and livestock over elephant conservation. However, our findings suggest that elephants could also provide benefits to rural communities through the enjoyment people receive from seeing elephants, as reported by Gadd (Reference Gadd2005), and through mechanisms such as job creation in ecotourism and providing labour in the transportation and timber industries.

Knowledge of and views on elephant conservation

The most recent assessment of the Asian elephant population in Myanmar was published in 2004 (Leimgruber & Wemmer, Reference Leimgruber and Wemmer2004). Despite the commitment and efforts of conservation agencies and the government of Myanmar to conserve the country's remaining 1,430–2,065 wild elephants (Leimgruber & Wemmer, Reference Leimgruber and Wemmer2004), recent research (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, McEvoy, Oo, Chit, Chan and Tonkyn2018) suggests that poaching may be occurring at a higher rate than previously suggested. Local knowledge can be valuable in determining trends in wildlife populations (e.g. Mallory et al., Reference Mallory, Gilchrist, Fontaine and Akearok2003; Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Mallory and Merkel2005), and could provide insights on elephant population numbers and distribution (Songer et al., Reference Songer, Aung, Allendorf, Calabrese and Leimgruber2016). That a majority of rural participants believed the elephant population is decreasing may suggest that the estimate from 2004 is now outdated.

Both rural and urban participants stated that poaching is the greatest threat to wild elephant populations. Sampson et al. (Reference Sampson, McEvoy, Oo, Chit, Chan and Tonkyn2018) reported that elephant populations in the rural areas where we conducted interviews had been targeted by poachers in the months immediately prior to our study. In addition, surveys conducted in Myanmar's legal wildlife markets have shown a 400% increase in elephant skin available for purchase during 2009–2014, suggesting a rise in consumer demand (Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Burn and Milliken2013; Nijman & Shepherd, Reference Nijman and Shepherd2014).

Some of the participants' responses were contradictory. For example, rural respondents supported protecting elephant habitat although they were less likely than urban participants to agree that habitat destruction and agricultural expansion were threats to elephants. This probably reflects the dependence of rural populations on farming and a reluctance to admit that these activities can be detrimental to elephants. Habitat loss is a major concern for wildlife conservation in Myanmar (Bhagwat et al., Reference Bhagwat, Hess, Horning, Khaing, Thein and Aung2017) and for Asian elephants throughout their range (Leimgruber et al., Reference Leimgruber, Gagnon, Wemmer, Kelly, Songer and Selig2003, Reference Leimgruber, Senior, Aung, Songer, Mueller, Wemmer and Ballou2008; Songer et al., Reference Songer, Aung, Allendorf, Calabrese and Leimgruber2016). Most respondents were aware that Myanmar has the largest expanse of continuous elephant habitat within the species’ range (Leimgruber et al., Reference Leimgruber, Gagnon, Wemmer, Kelly, Songer and Selig2003), a fact that conservation agencies could use in communicating the importance of regulating development of wild areas to maintain this unique and important resource.

Motivations for compliance with conservation laws

Myanmar's wildlife protection laws prohibit the killing of elephants and the possession of any elephant body part, with punishments of up to 10 years in prison (State Law and Order Restoration Council Law No.583/94.1994). Given that most participants believed that wildlife authorities would be likely to capture elephant poachers, it is unsurprising that both rural and urban participants indicated they are compliant with wildlife laws. However, as many participants indicated they were not fully aware of the wildlife laws in Myanmar, there is an opportunity for conservation agencies to invest in community education and engagement to ensure wildlife laws are better understood by citizens in both rural and urban areas.

Experiences with and perception of hunting and poaching

The drivers behind poaching can be complex. Some people poach wildlife for subsistence, others for commercial reasons or elevation of social status (Eliason, Reference Eliason1999). Many participants believed that poachers killed elephants for money. In Myanmar, the mean income of farmers is c. USD 1,000 per year (C. Sampson, unpubl. data). In contrast, people can be paid up to USD 4,000 for assisting a poacher to find an elephant (Z. M. Oo, pers. comm., 2017), and dried elephant skin is sold for up to USD 3.65 per square inch (Hla Hla Htay & Henshaw, Reference Henshaw2017). This provides considerable financial motivation for poaching or assisting poachers. Rural participants listed a greater variety of elephant body parts taken by poachers, aligning with reports from the Myanmar government, which suggests rural participants are more familiar with the wildlife trade.

Respondents in our study described observing violent behaviour by poachers and indicated they fear them, findings that are corroborated by reports that citizens are afraid to alert authorities to poaching activities for fear of retaliation (Kyaw Ko Ko, 2018). Elephants and other wildlife are high-value natural resources (Douglas & Alie, Reference Douglas and Alie2014), and the number of elephants poached appears to be increasing annually (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, McEvoy, Oo, Chit, Chan and Tonkyn2018). Local communities and the Myanmar government may need to protect citizens as populations of high-value species decline, as the activities of criminal organizations can result in social unrest and violence.

Implications for conservation

Understanding the attitudes and belief systems underlying citizens’ support for elephant conservation can help guide the creation of effective conservation strategies that integrate traditional values and modern science. Our interview survey indicates that the people of Myanmar recognize the importance of mitigating the expansion of human activities into wild areas, to protect elephants. This suggests they are probably willing to support conservation initiatives to protect elephant habitat. Similarly, highlighting the role of elephants in Myanmar's culture and their religious importance can encourage rural communities to adopt behaviours that benefit elephants.

Communities do not appear to be actively engaging in conservation activities to reduce poaching, despite their stated support for elephant protection and willingness to comply with relevant laws. Conversations with community leaders and local wildlife authorities suggest that actions such as assisting poachers may be financially motivated and driven by low levels of income and the high rewards paid by poachers. Given the deeply religious nature of many people in Myanmar and the Buddhist tenet that prohibits the killing of any living creature, developing and implementing programmes in collaboration with religious authorities to stigmatize working with poachers may help to counteract any financial incentives for doing so.

Our findings suggest that the government and associated elephant conservation agencies need to expand their mitigation efforts to include addressing the consequences of poaching and the illegal wildlife trade felt by human populations in Myanmar (e.g. elevated levels of fear and perceived potential for violence). Growing demand for elephant products (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, McEvoy, Oo, Chit, Chan and Tonkyn2018) may lead to further declines in the elephant population and greater efforts from poachers to locate them, potentially increasing perceived violence against communities. Other studies of declines of high-value wildlife have shown that, as more effort is needed to locate the animals, there can be an increase in organized crime and the forced conscription of children and adults into the illegal wildlife trade (WWF/Dalberg, 2012; Brashares et al., Reference Brashares, Abrahms, Fiorella, Golden, Hojnowski and Marsh2014).

Future studies should assess the part that local communities play in poaching (e.g. not reporting poachers, assisting them to locate elephants and transfer poached products) and their motivation for doing so. This information would help conservation organizations develop strategies to overcome any barriers to comply with anti-poaching laws. Additional studies that examine the structure of poaching operations, which is challenging given their illicit nature, could assist law enforcement in identifying and disrupting poaching activities. In addition, identifying vulnerable communities and community members may facilitate the development of educational outreach and intervention programmes, to prevent poachers from engaging them in activities that are both illicit and destructive to their own natural resources and livelihood security.

Acknowledgements

We thank the community members in Myanmar for their participation; U Khin Maung Gyi, U Myint Aung, Daw Khine Khine Swe and Aung Nyein Chan for their input and guidance in conducting the research; Zin Hline Htun, Nyi Win Kyaw Kyaw, Dr. Idd Idd Shwe Zin, Chan Nyein Aung, Zayar Soe, Ne Eindray Khin, Padang Aung, Bo Kyaw Htwe, La Pyae Wun, Kuang Thet Kyaw Zawe, Yan Lin Tun, Margaret Nyein Nyein Myint and Shane Thiha Soe for their assistance with fieldwork; and Christy Williams, Nicholas Cox and the staff of WWF-Myanmar for their support. Permission for this study was granted by the Myanmar Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. This study was funded by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Asian Elephant Conservation Fund (#ASE1648).

Author contributions

Study design: CS, JAG; fieldwork: CS, PS; data analysis: CS, JAG, SLR, PL; writing: CS, JAG, SLR, DT; revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards and was conducted with permission under the Memorandum of Understanding between the Myanmar Government and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. The questionnaire and study design were approved by the institutional review boards at Clemson University and the Smithsonian Institution (IRB Protocols #2014-187 and #HS17014, respectively), and we obtained prior, informed consent from the interviewees.