(Re)locating the subaltern

This essay is a meditation on the nature of the subaltern in archaeology. As envisioned by Antonio Gramsci and later on by the Subaltern Studies Group (SSG) in India, the word ‘subaltern’ is just a common noun used to define all subordinated groups, across time and space. This ‘invented’ concept thus escapes any social, cultural and historical boundaries, which gives the category of the ‘subaltern’ immense political flexibility—a flexibility often taken as indeterminacy that has hindered its application by archaeologists and social scientists alike, prompting criticism. It is to these deterrents and criticism that I turn in this article by focusing on the conceptual basis of the subaltern literature in archaeology, its problems and possible solutions.

Understood as a marginalized group vis-à-vis power, subalterns have entered the archaeological debate particularly in the fields of ancient Mediterranean archaeology (Delgado Hervás Reference Delgado Hervás, Mata Parreño, Pérez Jordá and Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez2010; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Reference van Dommelen, Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014; Zuchtriegel Reference Zuchtriegel2018), historical archaeology (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2016; Casella Reference Casella, Voss and Casella2012; Ferris et al. Reference Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014; Liebmann Reference Liebmann2012; Singleton Reference Singleton2009; Spencer-Wood Reference Spencer-Wood and Scott1994), and in the archaeology of the most recent past (Gnecco & Ayala Reference Gnecco and Ayala2011; González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014; Reference González-Ruibal2019b; Hansson et al. Reference Hansson, Nilsson and Svensson2019; McGuire Reference McGuire, Hicks and Beaudry2006; Pollock & Bernbeck Reference Pollock and Bernbeck2016). This is reflected in the steady flow of publications discussing subalterns from the early 2000s, and especially from the 2010s, in leading Anglo-American journals such as the Journal of Contemporary Past, International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Historical Archaeology, World Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory and Current Anthropology.

The political reasons for the emergence of subaltern studies in archaeology in the last decades, and in the social sciences more widely, are varied and range from the Dalit movements in India and the civil rights campaigns to put an end to racial segregation in the US to the confrontations within the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, the women's liberation movements, the Zapatistas and many other global fights for indigenous rights and the work of scholars from the former colonies in Western universities and institutions. More recently, the analysis of subaltern politics/ideas has been revitalized due to the global environmental disaster and the rise of Indigenous counterhegemonic and more sustainable worldviews, the Arab Spring, the Indignados and Occupy movements, Black Lives Matter, and much more. What these events demonstrate is that it has always been the subaltern, i.e. the Dalit, the black, the peasant, the indigenous, the woman, the poor, etc., who has changed her/his political and economic condition by fighting against the establishment at the time. (White) scholarship comes only later, mostly forced—and rightly so!—by subalterns.

Yet, as one of the reviewers of this article pointed out, the term ‘subaltern’ has become in a certain way an abstract academic cul-de-sac, a rather elusive and rarely theorized concept in archaeological literature (see also González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2019b, 104–6). In fact, many analyses of the subaltern—not only in archaeology—have overlooked the heterogeneity of these groups and the existing antagonisms within them. In their homogenizing endeavour, these studies have conflated the peasant proprietor or better-off subaltern with the poor peasant (Brass Reference Brass2017), or the discrimination of the Western female subject with the double effaced experiences of ‘Third World’ women (hooks et al. Reference hooks, Brah and Sandoval2004; Mohanty Reference Mohanty, Mohanty, Russo and Torres1991; Spivak Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988). In archaeology, scholars have very often conflated the subaltern with colonized and/or indigenous groups, disregarding the heterogeneity encompassed by the term (cf. Cañete Jiménez & Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez Reference Cañete Jiménez and Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez2011; Cuozzo & Pellegrino Reference Cuozzo, Pellegrino, Donnellan, Nizzo, Burgers and Osborne2016; Dietler Reference Dietler2010; Ferris et al. Reference Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014; Gnecco & Ayala Reference Gnecco and Ayala2011; Kistler & Mohr Reference Kistler, Mohr and Baitinger2016; but see González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2019a; Liebmann & Murphy Reference Liebmann and Murphy2010; Spencer-Wood Reference Spencer-Wood, Baugher and Spencer-Wood2010). They have denied colonial violence by celebrating a peaceful cohabitation of colonist/colonized groups (cf. Antonaccio Reference Antonaccio2013; Greco & Mermati Reference Greco and Mermati2011; Malkin Reference Malkin, Lyons and Papadopoulos2002; but see Delgado Hervás Reference Delgado Hervás, Mata Parreño, Pérez Jordá and Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez2010; Zuchtriegel Reference Zuchtriegel2018); or they have disproportionally represented indigenous people as vanquishers of European colonial powers—see especially the case of colonial Chile (Boccara Reference Boccara2008; Dillehay Reference Dillehay2007; Sauer Reference Sauer2015).

However, subalterns are neither (only) colonized people, nor homogeneous, quite the opposite. The subaltern is an invented concept that no-one has ever claimed. It does not refer to the identity of any known social group, nor is it an ideality shaped by political philosophers—peasant, proletariat, worker, citizen, indigenous, refugee, etc.—and asserted by historical beings for political reasons (Banerjee Reference Banerjee2015, 39, 42–3). In fact, Gramsci stretched his notion of subalterns to a wide range of oppressed groups (Reference Gramsci1975, 2286): ‘Often, subaltern groups are originally of a different race (different religion and different culture) than the dominant groups, and they are often a mixture of different races, as it is the case of the slaves’. He also included peasants, religious groups and proletarians into the subaltern category (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1975, 2286). In fact, Gramsci considered as subalterns all those subordinated groups whose political activity was ignored, misrepresented, or were on the margins of dominant discourses (Green Reference Green and Zene2013), similar to the SSG in India (Arnold Reference Arnold1984; Chaturvedi Reference Chaturvedi and Chaturvedi2000; Guha Reference Guha, Guha and Spivak1988a, 35).

Because the category of subalterns is not tied to any particular historical or cultural ideality, it resists instrumentalization and provides political flexibility and better agility to compare oppressed people in exposed living conditions (Banerjee Reference Banerjee2015; Hansson et al. Reference Hansson, Nilsson and Svensson2019). In order to do so, let me first think through a series of questions to frame better the concept of subalterns and its application to archaeology: Is the subaltern a political subject? How do we approach intersective oppressions among subalterns? How can archaeology approach the experience of subalternity?

Are subalterns political subjects?

One of the most debated issues by Gramsci and the Subaltern Studies scholars alike has been the question of the subaltern as a political subject, i.e. the agency of subalterns, which was very early called into question by Spivak (Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988). According to her, subalternity can be defined as a ‘position without identity … where social lines of mobility, being elsewhere, do not permit the formation of a recognisable basis of action’ (De Kock & Spivak Reference De Kock and Spivak1992, 45–6; Spivak Reference Spivak2005, 476). Further, Spivak contended that certain organized groups such as workers’ unions cease to be subalterns because they are organized and can speak against the elite, and therefore, for Spivak, they partake in the hegemonic discourse (De Kock & Spivak Reference De Kock and Spivak1992, 46).

Subalternity, as a ‘position without identity’ in Spivak's definition, draws a space of blockade and impossibility for action difficult to challenge. In fact, Spivak has received strong criticism since her 1988 publication for precluding the subaltern capacity of action (Mani Reference Mani1998; Parry Reference Parry2004, 19–28), for reducing the political consciousness of women to a discourse of female sexuality (Gopal Reference Gopal and Lazarus2004, 149–50), for ignoring class agency (Larsen Reference Larsen2001, 58–74), and for having a very narrow definition of who the subalterns are (Green Reference Green2002; Hershatter Reference Hershatter1993).

In her interpretation, Spivak aligns with other scholars who, when writing about slaves, defined them as ‘socially dead’ (Patterson Reference Patterson1982). Such a slippage between discourse and social reality elides important geographical and historical specificities. Besides, to see slaves and other unprivileged people as socially dead or as passive and mere victims of colonial and capitalist processes is to take at face value some of the more disgraceful allegations made by colonial officers and slave owners (Burnard & Heuman Reference Burnard, Heuman, Heuman and Burnard2011; Fanon Reference Fanon1952; Said Reference Said1989) and to confirm—ironically enough—the subalternization to which they have been subjected.

Contra Spivak (and Gramsci), Guha and other Subaltern scholars defined the subaltern as an agent autonomous from the elite, the State and bourgeois and colonialist ideologies (Guha Reference Guha, Guha and Spivak1988b,Reference Guha, Guha and Spivakc; Prakash Reference Prakash1994). Similarly, James Scott celebrated the agency of the subalterns against oppressive regimes by focusing on low-profile forms of resistance, such as tax evasion, false compliance, foot-dragging, pilfering, feigned ignorance, dissimulation, defamation and sabotage (Scott Reference Scott1985; Reference Scott1990; Reference Scott2013). Those studies have been caught, to different degrees, in binary questions of dominance and insurgence/resistance and, in other cases, in intellectual discussions on power and knowledge (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2000; Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee and Morris2010; Sharpe & Spivak Reference Sharpe and Spivak2003; Spivak Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988; Reference Spivak1990).

Emphasis on rebellion and resistance has also been the norm in archaeology, especially in postcolonial archaeology—something that has been reconsidered recently (Liebmann & Murphy Reference Liebmann and Murphy2010; Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot2015). Archaeologists sided with the oppressed subaltern against the elite or the colonial authorities by evidencing mainly uprisings and defiance, among slaves in colonial South Africa (Hall Reference Hall2000) and nineteenth-century Islamic Zanzibar (Croucher Reference Croucher2015), among indigenous and slaves alike in Portuguese Brazil (Gomes Coelho Reference Gomes Coelho2009; Orser & Funari Reference Orser and Funari2001), among indigenous women on the Spanish Orinoco frontier (Tarble de Scaramelli Reference Tarble de Scaramelli, Voss and Casella2012) and female convicts in nineteenth-century British Australia (Casella Reference Casella, Voss and Casella2012), or among peasants and colonized communities in ancient and modern Cyprus (Given Reference Given2004) and the ancient Mediterranean (Cañete Jiménez & Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez Reference Cañete Jiménez and Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez2011; Zuchtriegel Reference Zuchtriegel2018), to cite some examples. The overfocus on rebellion and resistance necessary in the early 1990s to criticize the colonial idea of natives as passive receptors of ‘superior cultures’ in archaeology has in turn obliterated other forms of subaltern agency such as cooperation and compliance with the oppressors.

Gramsci, however, was more cautious when dealing with subaltern agency and crafted the concept of ‘hegemony’ the better to understand both subaltern passivity and subaltern resistance when confronted with the elite. ‘Hegemony’ refers to the political leadership of a particular group based on the consent of the led group; a consent that is obtained by the diffusion and naturalization of the worldview of the ruling class (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, 56–7). Subaltern groups are thus subject and party to the hegemony of the ruling elite, even when trying to rebel. This is because ‘domination operates by seducing, pressuring, or forcing … members of subordinated groups and all individuals to replace individual and cultural ways of knowing with the dominant group's specialized thought—hegemonic ideologies that, in turn, justify practices of other domains of power’ (Collins Reference Collins2009, 287). Domination involves structural, disciplinary, hegemonic and interpersonal domains of power where ‘oppressions of race, class, gender, sexuality, and nation mutually construct one another’ (Collins Reference Collins2009, 203).

Only few archaeologists have engaged with the notion of hegemony in their discussions of subalternity (cf. Bernbeck & McGuire Reference Bernbeck, McGuire, Bernbeck and McGuire2011; Emerson Reference Emerson1997; Routledge Reference Routledge2014; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014), and even fewer with the concept of the ‘matrix of domination’ developed by Patricia Hill Collins (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2016; Franklin Reference Franklin2001). Yet, if we are to understand subalternity and subordination in all its complexity, we need to address how different axis of oppression are at work and reproduced by subalterns.

Intersective oppressions

Scholars today deploy the concept of subalternity to refer to the condition of a person or a group of people hierarchically positioned as subordinate within imperial and/or colonial structures, dictatorial systems, international capitalism, nation states, relations of race, patriarchy, heteronormativity, religion, caste, class, age, or occupation (Gidwani Reference Gidwani, Thrift and Kitchen2009; Green Reference Green2002; Reference Green2011; Mani Reference Mani1998). These categories of subordination are not exclusive, but deeply interrelated. In fact, it is only by understanding intersectionality at work, and more specifically the matrix of domination, that one can grasp the subaltern experience and its reproduction.

The concept of intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, inherits a long history of struggle and Black feminist thought (Collins Reference Collins2009; Hancock Reference Hancock2016). It stresses the structural and dynamic consequences of the interaction between several axes of oppression, namely race, ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic status, and so on, as inflicted onto marginalized people (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Oppression cannot be reduced to one type; quite the contrary. Intersectionality looks at the overlap of oppressions that work together in producing unique inequality and injustice within a person.

An individual is always situated within different domains of power, from the macrolevel of social organization to the microlevel of interpersonal relationships. Therefore, for Collins (Reference Collins2009, 227–8), ‘the overall social organization within which intersecting oppressions originate, develop, and are contained’ is what defines a ‘matrix of domination’. Although all matrices of domination encompass a combination of intersective oppressions, they are all different as to how the system of domination is organized, and thus they are historically situated and depend on the local context.

It is therefore the intersection of different axes of oppression in specific historical settings that constitutes the subaltern and, precisely because of that, subalternity is relational and dynamic within and in relation to dominant political forms (Crehan Reference Crehan2016, 60–62; Davis Reference Davis2011; Nilsen & Roy Reference Nilsen, Roy, Nilsen and Roy2015). Yet, although most subalterns can identify their own victimization within the structural system of oppression—race, gender, class, religion, etc.—they usually fail to see how their own actions in turn victimize/subordinate someone else. In fact, as Collins (Reference Collins2009, 287) points out, ‘a matrix of domination contains few pure victims or oppressors’; for each individual, depending on their position within society, experiences different degrees of disadvantage and privilege from the multiple oppressive systems that frame everyone's lives. These experiences are contradictory within a person, and they are so routinized and recurrent in the everyday practices that they often go unnoticed—warns Collins (Reference Collins2009, 287). It is thus to the day-to-day experience that I turn now.

The everyday life of subalterns and their senso comune

Senso comune is a particularly useful tool to approach the everyday life of subaltern groups. Contrary to the English ‘common sense’ (meaning ‘good sense and sound judgement in practical matters’, according to the Oxford English Dictionary), senso comune refers to the beliefs and opinions of the masses that create a practical consciousness to confront their everyday life successfully. Since archaeologists deal mostly with the everyday life debris of people when excavating a site, exploring this concept and its application to archaeology could help us flesh the material remains to get a better understanding of subaltern people.

Gramsci defined senso comune as

not a single unique conception, identical in time and space … it takes countless different forms. Its most fundamental characteristic is that it is a conception which, even in the brain of one individual, is fragmentary, incoherent and inconsequential, in conformity with the social and cultural position of those masses whose philosophy it is. (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, 419)

Common sense is thus, for Gramsci, complex, unsystematic and messy. Based on foundational premises found in every human group, common sense provides a worldview that structures the basic sceneries within which individuals are socialized, including orientations that are historically and unconsciously adopted from dominant groups (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, 326–7). These worldviews in which common sense is built upon are essential for every human being to understand reality, to interpret it and to act effectively within it, but they are also contradictory and uncritical (Baratta Reference Baratta2010; Crehan Reference Crehan2016, 46–7; Liguori Reference Liguori2005). Importantly, worldviews are modes of and for reality and thus they are different from one group to another, and that includes different segments within the same society—indeed, ‘every social class has its own “common sense”’ (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1985, 420). This leads us again to the matrix of domination and the different systems of oppression and privilege that occur in a contradictory manner, i.e. everyday actions that reproduce or contradict ideology, being aware of your own victimization but not of your subalternization of others, etc.

The juxtaposition of the matrix of power developed by Collins and Gramsci's senso comune provides us with a broader and more complex framework to analyse subalternity and how it is reproduced within a given hegemony. Since subalterns tend to be ignored by official documents (but see Davis Reference Davis2011), and it is in the day-to-day practices of interpersonal relations that subalternity is assumed and reinforced (Collins Reference Collins2009, 287), the analysis of everyday material culture emerges as a very powerful tool to approach the subaltern experience (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014; Hansson et al. Reference Hansson, Nilsson and Svensson2019; Liebmann Reference Liebmann2012; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006; Reference van Dommelen, Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014). Let me start by exemplifying this theoretical and methodological framework through the analysis of two case studies from Chile and Ethiopia.

The Reche and the Spanish Empire: Chile, sixteenth–nineteenth centuries

The Reche (today Mapuche)—inhabitants of central-southern Chile (Ngulu Mapu) and Argentina (Puel Mapu)—have been praised historically by anthropologists and archaeologists alike for vanquishing the Spaniards and their imperial power in the seventeenth century (Boccara Reference Boccara2008; Dillehay Reference Dillehay2007; Sauer Reference Sauer2015). This is because, after many years of uprisings and war, the Reche defeated the Spaniards in 1598 and laid waste to all the colonial cities south of the Bíobío River (c. 500 km south from Santiago), forcing thousands of Spaniards and their allies to flee to Santiago. The Crown recognized the Reche ownership of their territory and established the imperial frontier along the Bíobío River in 1641. Despite being a great triumph—especially if compared with the fate of other colonized groups—overemphasizing this indigenous deed obscures ongoing colonial violence in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and downplays the suffering of subalterns in the region. Further, assuming the fierce resistance of all Reche against the Spaniards draws a homogeneous picture of indigenous people—and of the colonists—during the colonial period, disregarding other forms of agency such as collaboration and compliance with the colonial regime, or the subalternization of other segments of society by the Reche themselves.

The Reche

The Reche were a patriarchal and patrilocal society that practised exogamic polygyny—sororate marriage, specifically. Women were exchanged among different lineages through a bridewealth system in which the bride's family received animals, hand-woven blankets and clothing from the groom's family in return for the loss of their daughter (Bengoa Reference Bengoa2003, 83). This type of exchange created extensive kinship relationships among different and far-away communities, as well as intensive exchange networks across the Wallmapu—the Reche-Mapuche territory (Bengoa Reference Bengoa2003, 79–86).

The household or lov was the basic social unit among the Reche, headed by the lonko [the father, referred to as ‘cacique’ by the Spaniards]. Several lovs formed a rewe, and several rewes an ayllaregue—supra-organizations that took shape depending on ritual festivities and war, organized heterarchically and led always by men (Bengoa Reference Bengoa2003, 159–70). This type of social structure was unconsciously adopted from the hegemonic leaders by all the Reche, as part of their common sense. Common sense, as we have seen, is contradictory and differs between societal segments. Many men within these communities did not occupy positions of power, and thus were subalternized by their leaders, but were nevertheless in charge of their lovs. Quite contrarily, women could not occupy positions of power or become the head of a lov, but accepted and reproduced their subordination within the social and political structure of the Reche communities.

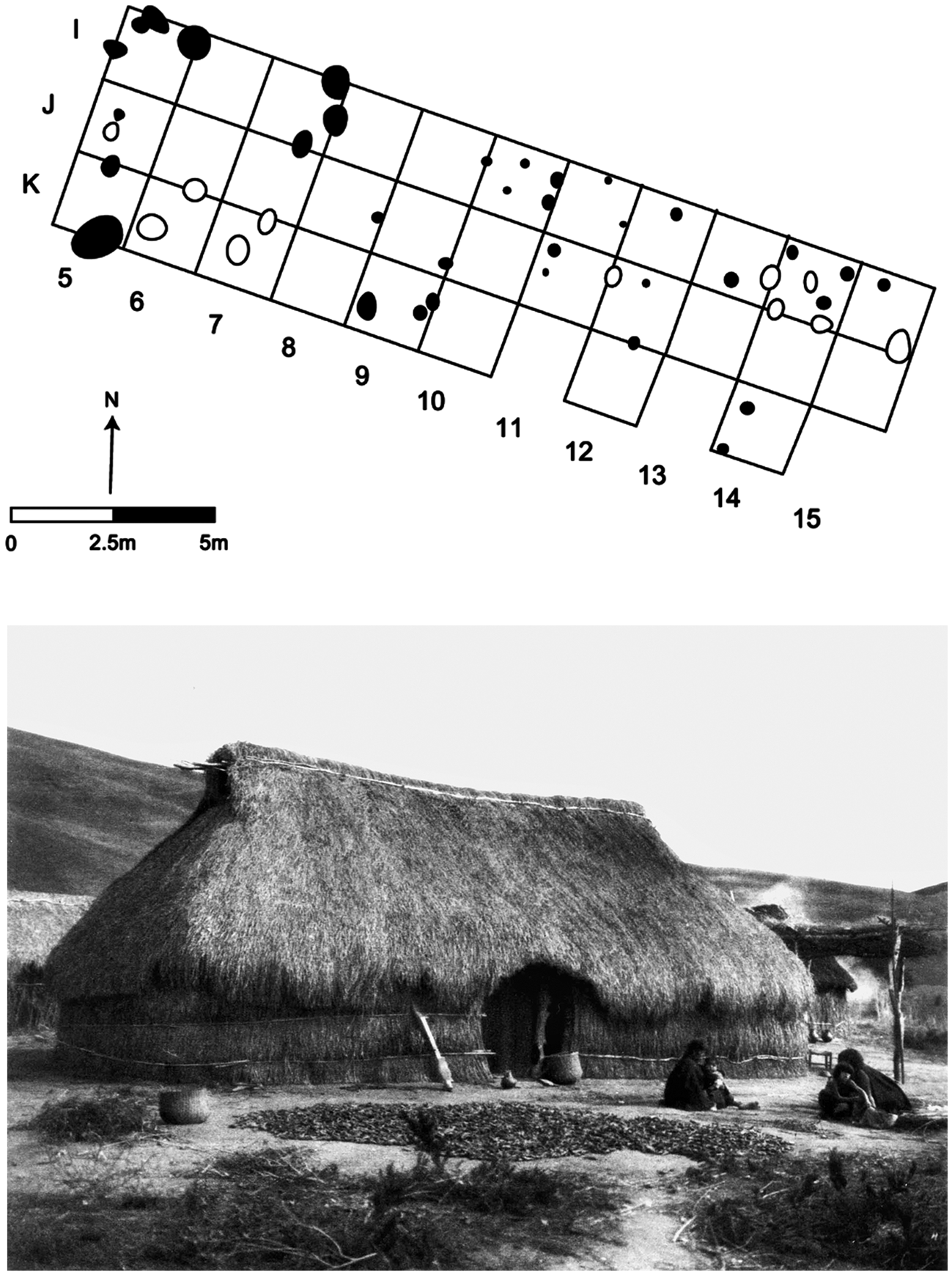

The ruka [house] was the centre for everyday life activities among the Reche communities of central-southern Chile, and continues to play a pivotal role today (Fig. 1). The open-area excavation of the Km 0-Enlace Temuco site in central Chile permitted the study of a ruka dating to the sixteenth century for the first time, yielding important information on everyday activities (Ocampo et al. Reference Ocampo, Mera, Munita and Massone2005). Archaeologists uncovered two hearths (largest black circles in I5 and K5 in Figure 1a) and several circular areas with charcoal (I5, I7 in Figure 1a) interpreted as previous hearths no longer in use. The chroniclers concurred that there were as many hearths as wives living under the same lov, and that each of the hearths had several pots, spits and pans (Zapater Reference Zapater1978, 53). If we accept this information, the two hearths would indicate the existence of at least two wives living in the ruka and married to the lonko.

Figure 1. (Above) Archaeological remains of a Reche ruka (after Ocampo et al. Reference Ocampo, Mera, Munita and Massone2005 & Dillehay Reference Dillehay2014, 108); (below) postcard showing a ruka Mapuche in the early twentieth century.

The ruka did not present any internal division, but it seems that different activities were carried out in distinctive areas within the house. In the western side of the ruka, archaeologists unearthed numerous fragments of pottery, among them pots, tableware, and a tobacco pipe surrounding the hearths, which indicates the presence of cooking activities but also the social and ritual practice of smoking by the lonko. On the eastern side, associated with the post-holes, there were many and varied lithic artefacts, including several grinding stones and hand stones, an axe, as well as scrapers, flakes and blades. Grinding activities were quite prominent, as well as the preparation of leather and probably basketry, tool making and wood cutting and carving.

The existence of different types of stone raw materials (basalt, quartz, pumice, obsidian) coming from volcanos in the Andes 100 km away attest to the medium- to long-distance networks in which the mainland Reche were involved, most likely as a result of marriages. These types of networks as providers of raw materials are also demonstrated by the analysis of obsidian from the sixteenth-century site of Santa Sylvia, where black obsidian came from a nearby volcano and red obsidian came from Neuquén in Argentina, 150 km away (Sauer Reference Sauer2015, 111–12). Either as bridewealth or as a consequence of the establishment of a reciprocity system because of the marriage, obsidian was clearly exchanged between coastal, mainland and Andean groups.

Similar material culture to that found at Km 0-Enlace Temuco was unveiled from the domestic sites of La Mocha Island in the Pacific (Quiroz & Fuentes-Mucherl Reference Quiroz, Fuentes-Mucherl, Becker and Uribe2012; Quiroz & Sánchez Reference Quiroz and Sánchez1997); and surveys and test pits in the area of Valdivia yielded comparable evidence before and during the colonial period (Marín-Aguilera et al. Reference Marín-Aguilera, Adán Alfaro, Urbina Araya, Mander, Mindgley and Beaule2019, 89–91). This means that the ruka was the materialization of both the social structure and the interpersonal relations of all Reche communities between the fourteenth–fifteenth century and the nineteenth century (Fig. 1b).

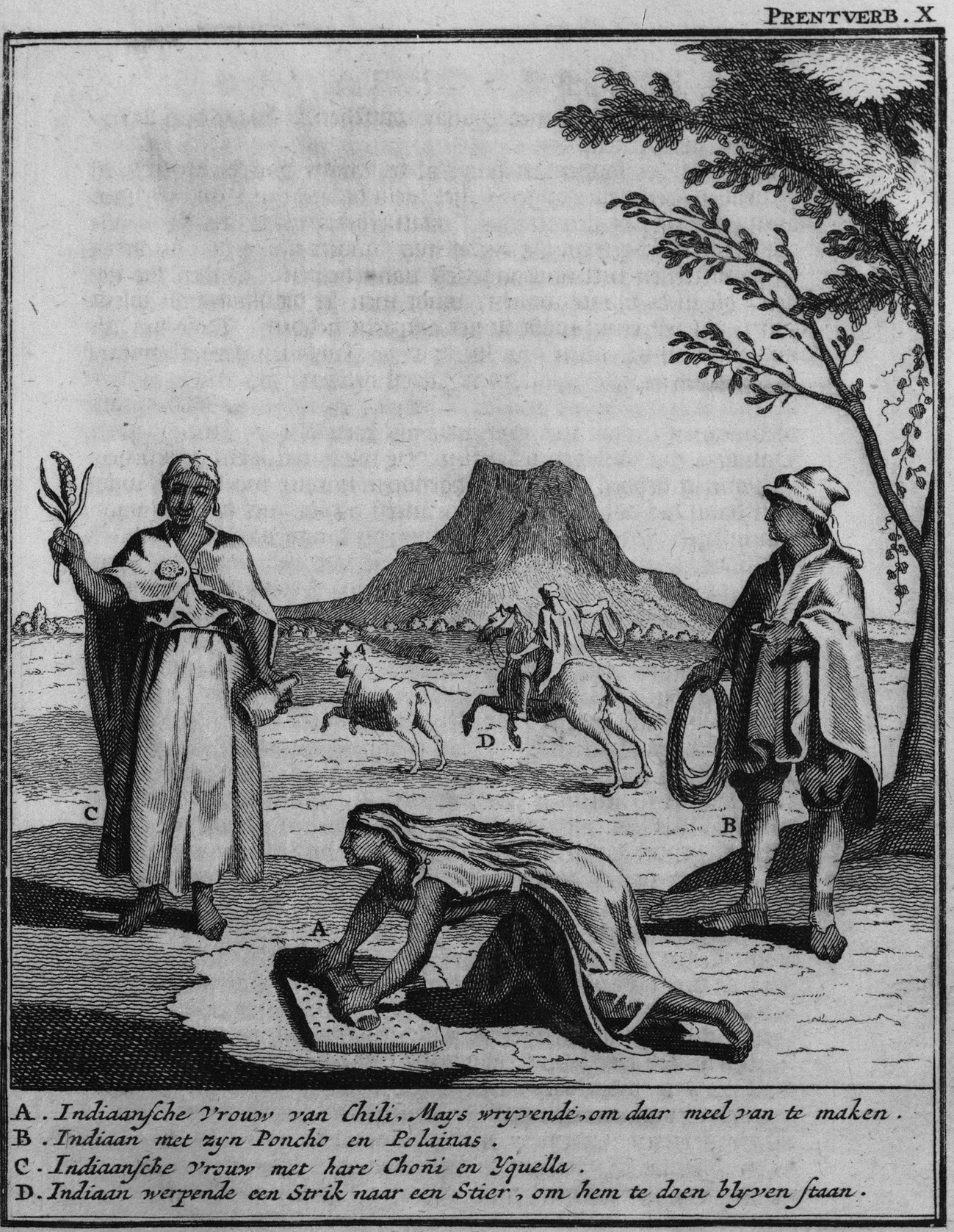

Spanish chronicles and ethnography provide us with details regarding the sexual division of labour among the Reche, accepted and unconsciously reproduced by all community members. Ploughing the land was a communal activity carried out by several lonkos from different lovs, whilst women were in charge of sowing; after which the lonko who owned the fields organized a big festivity with food and alcoholic drinks—prepared by his wives—for all participants (Zapater Reference Zapater1978, 52–3). Other important economic activities were boat building and fishing and sea-food gathering—done by men—and trade, basketry, textile and pottery making carried out by women (Bengoa Reference Bengoa2003, 79–83; Zapater Reference Zapater1978, 54, 90–93) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Reche women engaged in everyday activities. (Engraving for A.F. Frézier, Relation du voyage de la mer du Sud aux côtes du Chili, du Pérou, et du Brésil, fait pendant les années 1712, 1713, & 1714. (Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.)

The more wives a lonko had, the wealthier he was, for he profited from a greater exchange network and higher agricultural and textile productivity. Not all lonkos could pay the bride price several times and thus have more than one wife; and not all wives were equal within the lov. The first one seemed to have been the most important wife—accepted as such by the others—in charge of organizing the work of all other wives in the lov (Zapater Reference Zapater1978, 63). We see here how socio-economic differences and women's status played a role in the worldviews of each lonko and each wife.

The Spanish conquest and colonization

The Spanish Crown formally abolished indigenous slavery in 1542 (New Laws), a year after the foundation of the first colonial city in Chile. However, ‘rebel Indians’ could be officially enslaved, no matter whether children or adults. As a result, thousands of Reche who waged war and rebelled against the Spaniards were owned and/or sold as slaves to other Spaniards living in other regions of the Empire; females were raped and constrained to work in colonial households, and many men swelled the encomiendas—forced tribute and labour system—in different regions of Chile (Contreras Cruces Reference Contreras Cruces2016; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela, Gaune and Lara2009).

The Reche were confronted with a hierarchical political system and with an alien social structure in which the white Spaniards and their criollo descendants were on top, whereas the indigenous, Africans and their descendants were below. There was social mobility, however, and indigenous people and freed Africans could climb the social ladder (Rappaport Reference Rappaport2014; Sater Reference Sater and Toplin1974; Walker Reference Walker2017). In fact, in the period between 1564 and 1801, 60.9 per cent of all indigenous last wills in colonial Chile belonged to Reche individuals who integrated well into the colonial society (Retamal Ávila Reference Retamal Ávila2000, 26), and freed Africans got encomiendas in Chile with indigenous forced labour (Sater Reference Sater and Toplin1974).

The Reche common sense, however, or their heterogeneous bundle of taken-for-granted worldviews, suffered a profound transformation in which a different hegemonic worldview and a new set of everyday practices were imposed upon them, replacing the previous unconscious adoption of their own political, social and cultural structure. Yet, the Reche elite also profited from their new situation, possessing themselves indigenous people as domestic servants and slaves (Retamal Ávila Reference Retamal Ávila2000, 76–7).

Beyond the imperial frontier at the Bíobío River, wars, slavery and the encomienda system decimated the Reche population and their resources. Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Reche carried out malocas [raids to get animals and other goods] to implement justice among different lovs (Parentini Reference Parentini1999). However, in the late seventeenth century and especially in the eighteenth, the scarcity of resources led to a transformation of the malocas from a justice system to a fight over the control of resources among different lovs, which included incursions into Spanish territories to steal livestock, horses and women (León Reference León1991).

This transformation of the malocas heavily impacted the Reche bridewealth and reciprocity system, as well as their interpersonal domain and social structure. By taking Spanish women as captives, the lonkos avoided the bride price but added wives and thus labour force to the lov. In fact, the Reche forced female captives to dress as Reche women, work in the fields, prepare and cook food and drinks, spin and weave textiles and have intimate relations and procreate with the lonkos who owned them (Lázaro Ávila Reference Lázaro Ávila1994). They basically forced them to become Reche. New language, new behavioural rules, new beliefs and rituals and new material practices joined the existing agglomerate of the Spanish women's common sense, that mutated considerably.

Excavated colonial contexts in today's central-southern Chile always display a mixture of Spanish and Reche material culture, the latter often being more numerous (Dillehay Reference Dillehay2014, 97; Marín-Aguilera et al. Reference Marín-Aguilera, Adán Alfaro, Urbina Araya, Mander, Mindgley and Beaule2019; Sauer Reference Sauer2015, 96–111). This indicates that even when the Reche were domestic servants, slaves, or forced labourers in encomiendas, they kept their everyday materiality and could cling to their everyday practices, such as their own cuisine cooked and served in their own ceramics or smoking tobacco from their own pipes, in the case of the men.

Yet, in the rukas excavated and dated to the colonial period, the amount of Spanish material culture is either non-existent or extremely scarce (cf. Adán et al. Reference Adán, Urbina, Prieto, Zorrilla, Puebla, Calvo and Cocco2016). This means that Spanish captives, and particularly females, went through an almost complete transformation of their common sense. Everyday activities such as food preparation and consumption, dressing habits and the Reche socialization of their new-borns were completely alien to them. They suffered the sexual abuse by the lonkos that the Spanish men inflicted on indigenous and African females taken as slaves and domestic servants. Female bodies became the site of colonial violence in Chile, but Spanish females eventually became integrated into the Reche society as any other wife, whereas both indigenous and African slaves continued to be servants. The matrix of domination was, thus, quite different between women.

The Spanish conquest and colonization of Chile brought misery and suffering not only to Africans, indigenous people and their descendants, but also to many Spanish men and especially women. While Spanish elite men mostly kept their common sense intact (same hierarchical system, same religion, similar houses and everyday material culture, etc.), all Africans, most indigenous people and many Spaniards saw their worldviews and systems of oppression, previously unconsciously understood and performed, dramatically change, destabilizing their life courses. Hence, harping on the Reche resistance and defeat of the Spaniards neglects the heterogeneity of the Reche and silences the enduring of imperial violence by many Reche communities, among other ethnic groups in colonial Chile.

The Gumuz, Ethiopia (sixteenth century–today)

The Gumuz inhabit the present borderland between Sudan and Ethiopia, where they have lived since at least the fifteenth century ad according to historical sources, although it is likely that they inhabited the area already in antiquity (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 93–4). Through different strategies of resistance, these groups have, to different degrees, managed to avoid their full incorporation into the State (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014; James Reference James2016; Jedrej Reference Jedrej2006). Heavily racialized and discriminated against—described as evil black and wild animals (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 91–2)—the Gumuz have been raided and enslaved for centuries by their neighbours (Ahmad Reference Ahmad and Clarence-Smith1989; Reference Ahmad1999; Taddesse Tamrat Reference Taddesse Tamrat1988).

The Gumuz are always described as ‘egalitarian societies’ sustained by ‘egalitarian ethics’ because of the absence of hierarchies and socio-economic differences (Feyissa Dadi Reference Feyissa Dadi2011, 266; González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014; James Reference James1979, 19). Yet egalitarian societies, at least in the case of the Gumuz, are not equal. Women occupy a subaltern position within their communities (Hernando Reference Hernando2017; Reference Hernando, Muñoz Fernández and del Moral Vargas2020). Thus, behind a history of cruel violence and subalternization lies a history of gender asymmetries that is neglected by the discourses crafted by most anthropologists, archaeologists and sociologists that have worked with/about the Gumuz.

The shared racial oppression

Racial ideas in Ethiopia date back to at least 400 bc, when a Sabean inscription refers to ‘black’ and ‘red’ subjects of a king (Taddesse Tamrat Reference Taddesse Tamrat1982, 342). Highland Ethiopians have never seen themselves as black, but as red, and have always perceived lowland groups—among them the Gumuz—as blacks, and thus subject to slavery (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 92–4). Slavery of lowlanders was made official by the Fethä Nägäst [Law of the Kings] dating to the thirteenth century, which permitted the enslavement of non-Christian war captives and of polytheists living on the fringes of Christian Ethiopia (Ware Reference Ware, Eltis and Engerman2011, 73). Behind this profitable slave market was the acquisition of Indian textiles by Christian Abyssinia (Eaton Reference Eaton2005, 108–9). In order to obtain them, the Solomonic kingdom refrained from baptizing pagan communities (even if some begged to be Christian) so they could capture and sell them to Muslim traders in exchange for Indian commodities, according to the Jesuit Gonçalo Rodrigues in 1556 (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1997, 252–3). Indeed, between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, Muslims and Christians acquired most of the slaves from pagan communities (Eaton Reference Eaton2005, 108–10), and c. 10,000–12,000 of them annually left Ethiopia (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1997, 253). From 1640 onwards, the Ethiopian state expanded its slave-raiding expeditions towards its western frontier with Sudan, the area inhabited by the Gumuz (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1990, 111–12). Defined as ‘blacks’ and derogatorily referred to as ‘Shanqalla’, the Gumuz suffered slave-raids until at least the mid twentieth century (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 94–5). The traveller James Bruce explained when and how those raids took place in the eighteenth century:

on the accession of every new king to the throne of Abyssinia, there is, among other amusements, a general hunt after the Shangalla. Inroads are made upon them, also, from time to time by the governors of the adjacent countries, who are obliged to render as tribute to the king of Abyssinia a certain number of slaves. When a settlement is surprised, the men are slaughtered, the women who are not slain kill themselves, or go mad; and the boys and girls are taken to be educated as slaves for the palace and the great houses of Abyssinia. (Bruce Reference Bruce1860, 81–2)

The Gumuz villages on the Sudanese–Ethiopian border clearly embody the fear of being raided. Entering a Gumuz settlement is a ‘similar experience to that of accessing a labyrinth, with closed alleys, narrow passages, funnel-shaped entrances and exits, countless junctions and unexpected open spaces’ (González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, Ayán, Falquina, Ayán, Mañana and Blanco2009, 88). Since one cannot see the whole village, it is difficult to get an idea of its layout, making it easier for the Gumuz to defend themselves, but also better to escape a slave raid. The act of escaping is better expressed by the construction of the Gumuz house, that always has a back door for the sole purpose of fleeing slave raids (Fig. 3)—even today, when they do not suffer them. The architecture of trauma is deeply embedded in the bodily experience of the Gumuz, and thus, as the team of archaeologists working on the Gumuz territory point out, ‘Gumuz identity is inseparable from their houses: they are built together’ (González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, Ayán, Falquina, Ayán, Mañana and Blanco2009, 88). This type of architecture is the material debris of the worldview in which the Gumuz have been socialized for centuries and, according to which, they have charted their life courses.

Figure 3. Typical back door of a Gumuz house. (Photograph: courtesy of Alfredo González-Ruibal.)

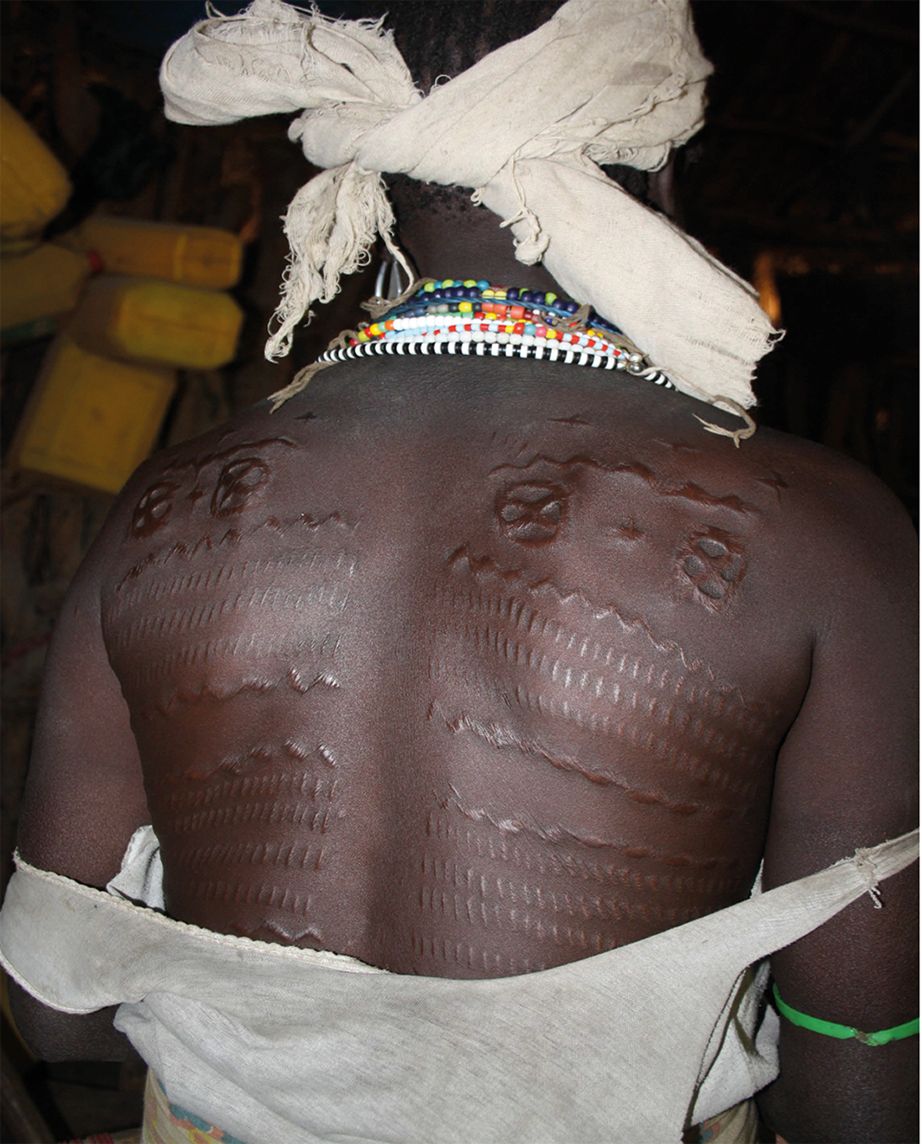

Trauma is also inscribed in their bodies through scarification (mokota). One particular type of this body decoration that is almost always present is an encircled cross, the shaŋgi. The first evidence of this type of scarification comes from ad 1600, when the governors of the Funj Kingdom, who conquered the Ethiopian–Sudanese borderland, marked their slaves and herds with it (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 126). As a symbol of an experience they cannot escape—slavery—this type of scarification is both a remnant of an unconsciously adopted hegemonic worldview from the traumatic Funj period and the social landscape in which the Gumuz are socialized. Indeed, far from seeing it as a symbol of subalternity, they see it as part of their identity as Gumuz (Fig. 4). Men usually have it only on their cheeks, whereas women have them on their back, arms, breasts and stomach as a sign not only of group identity but of beauty (Hernando Reference Hernando2017, 455–6). Associated with fertility, the shaŋgi also features prominently in the decoration of Gumuz material culture, such as in their granaries and in the sticks Gumuz females use for dancing (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 126).

Figure 4. Gumuz woman with scarification on her back—note the encircled cross. (Hernando, Reference Hernando2017, fig. 7, with permission.)

The Gumuz have also reworked, in quite a contradictory way, their association with the Funj in their oral tradition. In fact, they see themselves as Funj:

Why do they [the Ethiopians] say Shankalla? The reason is this: because they want to sell these Shankalla people and make them slaves. But we are Funj … The Funj are the people who used to be called el hurra [freemen in Arabic]; now we are not slaves, but Funj and freemen. (Quoted in James Reference James and Archer1988, 135)

This could be also the reason—or one of the reasons—the Gumuz continue to use the shaŋgi as part of their everyday bodily and visual landscape. It would explain as well why this scarification is far more popular among the Gumuz than among other groups that were also enslaved but scarcely use it (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 126).

As part of their shared common sense, the Gumuz have also inherited a sense for resistance against the abuse they have historically suffered. Their everyday material culture for preparing food and consuming it is made of basketry or clay, and they rarely rely on ceramics, baskets, or plastic containers coming from their neighbouring groups or from the market, in contrast to the nearby Agäw (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 119–23).

Until the mid nineteenth century, the Gumuz exchanged sisters in marriage with the Agäw and frequently traded with them, but in the late nineteenth century the situation changed (James Reference James and Archer1988, 134–5). The Agäw completed their conversion to Christianity by the second half of the nineteenth century and thus did not suffer more slave-raiding; moreover, they acted as tribute collectors from the Gumuz for Christian Ethiopia (Ahmad Reference Ahmad1995, 56–8). The Gumuz were thus left between the Christian empire of Ethiopia and the Madhist Sudan, whose expansion and conversion policies to Christianity and Islam, respectively, heavily pressured them. New slave-raids and pillage by both empires against the Gumuz in the early twentieth century forced hundreds of them to flee and abandon their villages (Ahmad Reference Ahmad1995; Reference Ahmad1999; James Reference James and Archer1988). In fact, there is a hiatus in the archaeological record of this period in the region attesting to the escape and exile of many Gumuz communities (González-Ruibal & Falquina Reference González-Ruibal and Falquina2017, 196–7). This recent traumatic experience probably explains the reluctance of the Gumuz to use alien material culture, particularly from the Agäw, who however do use Gumuz pots as part of their everyday ceramic repertoire.

The intersection of gender

United by racial oppression and slave-raiding, the Gumuz display another level of subalternity that is not external to them but internal to their worldview and practices: that of the Gumuz women (Hernando Reference Hernando2017; Reference Hernando, Muñoz Fernández and del Moral Vargas2020). Even when being racialized and enslaved, it is young women and girls who historically suffered most slave raids (Ahmad Reference Ahmad1999, 439). Gumuz women carry out most economic tasks such as household chores, weeding and ploughing on the farm, collecting firewood, carrying heavy loads to the market, fetching water and taking care of children (Birhan & Zewdie Reference Birhan and Zewdie2018; Zeleke Reference Zeleke2010). In many areas, Gumuz girls are not schooled (Zeleke Reference Zeleke2010, 42), and women are beaten by their husbands (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 132–3).

Women are believed to be polluted at menarche and during the first two menstrual periods, as well as when giving birth, and they are therefore secluded from the community (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 132–3). This type of subalternization, accepted and reproduced by Gumuz women, is embodied by architecture. During their first two menstrual periods, women live in a separate hut called mets'a gaya (Fig. 5). Further, there are specific types of material culture that women need to use when menstruating so as not to mix with the rest of everyday material culture shared by the family and group. Among these items, they are required to wear a particular belt around their waist, to sit on specific stools only used during menstruation (tuga gaya) and to use specific pots (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 145–6; Kidanemariam Demellew Reference Kidanemariam Demellew1987, 23, 26).

Figure 5. A Gumuz village with main house (right) and kogwa for menstruating teenagers (left). (Photograph: courtesy of Alfredo González-Ruibal.)

Mothers give birth in isolation in the woods without making much noise during labour because it would make the Missa [spirits] angry; after which, they need to remove the placenta, cutting the umbilical cord, and washing the newborn themselves (Kidanemariam Demellew Reference Kidanemariam Demellew1987, 22; Zeleke Reference Zeleke2010, 36). Many women have died giving birth because the baby was in the wrong position during labour, and many others could not return home until they were completely clean from blood many days later –and many Gumuz women are now rebelling against these practices and beliefs (Negash Reference Negash2017).

Both menstruation and pregnancy practices have been adopted and reproduced by Gumuz women for centuries as part of their common sense, and Gumuz beliefs shared by the community have acted to consolidate them. Whilst materiality embodies the pollution taboos around menstruation among the Gumuz—huts, material culture—the material silence of giving birth is overwhelming.

Gumuz women are thus embedded in a matrix of power in which they suffer the intersecting oppression of race and gender, whereas men experience only the racial oppression. Lack of social hierarchies and communal and shared practices, among other aspects, point to egalitarian societies (González-Ruibal Reference González-Ruibal2014, 112–24), but the Gumuz are far from equal in terms of gender (Hernando Reference Hernando2017; Reference Hernando, Muñoz Fernández and del Moral Vargas2020). Our reiterative narratives of egalitarianism have the power to produce and stabilize the very effects of subalternity, silencing, in the case of the Gumuz, the subalternization of women.

Subaltern debris

The interest in the subaltern(s) in archaeology runs parallel to a general interest in questions of power, agency and resistance in the humanities and social sciences. Eagerly adopted by some and rejected by others, the concept of the subaltern has the potential to overcome identity deadlocks and provide a useful framework to compare the manifestation of subalternity and its reproduction by subalterns themselves. The combination of Gramsci's senso comune and Collins’ ‘matrix of domination’ further strengthens a theoretical and methodological skeleton to identify the different elements which comprise subalternity and the social realities to which they are linked. It stresses the situational and relational context in which subalterns chart their life courses. Most importantly, the concept of the subaltern as the axis of intersecting oppressions escapes homogenizing visions of human groups and their material culture. The debris of everyday practices emerges thus as a powerful tool to map the contradictory elements of common sense and how materiality embodies the different intersecting oppressions at play within subalterns.

Due to limited space, the two case studies briefly examined here do not aim to be conclusive regarding the application of the proposed theoretical and methodological framework, but to open new ways of thinking about subaltern experiences through the use of material culture. In Chile, the ruka functions as the embodiment of the Reche common sense in the way it structures different social and economic activities as well as people living under its roof. It also provides a shared point of departure for all Reche in central-southern Chile, being the basic mechanism through which individuals internalize hegemonic worldviews and effective tools to understand reality and to act upon it. For Spanish captives, however, the ruka represents the alienation and violence suffered and lived as part of their captivity, and a completely new set of heterogeneous debris of worldviews and daily practices waiting to be understood to make sense of their new experience. The material culture of Spanish houses and haciendas, however, allows indigenous communities to cling to their traditional social practices. Yet they are immersed in a completely new matrix of domination which I could only sketch out here. Differences between forced labourers and Reche elite are important, for the former suffered racial, socio-economic, religious and gender oppression, whereas the latter did not suffer the tyranny of poverty and lack of freedom.

The case of the Gumuz is quite different, as they cling to communal and egalitarian practices to avoid the development of social and economic hierarchies. The Gumuz, however, have shared a common axis of oppression for centuries, i.e. race, for which they have been subalternized by every group and expanding state or empire since the fifteenth century and, most crucially, enslaved and killed. Still, Gumuz women experience a double subalternization by the intersection of their racialized oppression shared with men and the violence and subjugation practices felt as women.

What the combination of Gramsci's senso comune and Collins’ ‘matrix of domination’ offers archaeologists is a way of thinking about everyday practices that encompasses both their contradictions and flexibility, as well as their subjective diversity. By fleshing material culture and keeping the focus on how materiality embodies different systems of oppression, subalternity can be explored.

Acknowledgements

This research was generously funded by the McDonald Grants and Awards 2017–2019 (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge) and the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (HAR2016-77564-C2-2-P). I thank Almudena Hernando for her comments and image of the Gumuz woman, and Alfredo González-Ruibal for the two other images of the Gumuz. I am also grateful for the feedback of the editor and three reviewers on an earlier version of this article, and for the long discussions about subalternity and Gramsci with Peter van Dommelen.