LEARNING OBJECTIVES

-

Understand how TMS works in the treatment of depression

-

Appreciate which patients will benefit from TMS and when it is contraindicated

-

Be aware of the current clinical guidance for the use of TMS as a treatment for depression

The American Psychiatric Association (APA; 2013) describes major depressive disorder as a medical illness that affects how a person feels, thinks and behaves, causing persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. It can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems and usually requires long-term treatment. However, between 20 and 40% of people with depression do not recover following standard treatments such as medication and psychotherapy (Reference Bauer, Whybrow and AngstBauer 2002).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a form of neuromodulation, is a non-invasive, non-convulsive technique used to stimulate neural tissue. The procedure involves the placement of an electromagnetic coil to deliver a short, powerful magnetic field pulse (1.5–2.0 T) through the scalp and induce electric current in the brain. TMS is a relatively new treatment for psychiatric disorders, but it has been well established in neuroscience research experiments and in clinical applications for neurological conditions. Additionally, it has been used as an investigative tool in neuronal diseases (Reference Groppa, Oliviero and EisenGroppa 2012). Box 1 summarises the applications of TMS.

BOX 1 What is TMS and when is it used?

-

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is the application of magnetic pulses over the scalp to produce electrical activity in specific regions of the brain

-

In repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) treatment, the electromagnetic coil is switched on and off repeatedly to produce stimulating pulses

-

The main indication for TMS treatment is unipolar treatment-resistant depression without psychotic symptoms, especially in patients who do not want to consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

-

Treatment of depression using TMS usually involves daily sessions 4 or 5 days a week for 4–5 weeks

Treatment

Barker and his colleagues in Sheffield first demonstrated that TMS could be applied to stimulate the cerebral cortex (Reference Barker, Jalinous and FreesonBarker 1985). The stimulation can be delivered either as a single pulse or as repetitive pulses (repetitive TMS or rTMS). The clinical use of TMS involves repetitive pulses applied in trains of stimulation over a target area of the cortical region of the brain. The response to the treatment is influenced by various factors, including the frequency, intensity and duration of the stimulus, and its ability to excite or inhibit particular neuronal functions (Reference Hoogendam, Ramakers and Di LazzaroHoogendam 2010). The strength of the magnetic field used for clinical applications is similar to that of a standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (Reference Rossi, Hallett and RossiniRossi 2009).

Putative mechanism of action

As is the case for many other antidepressant treatments that are available in clinical practice, the exact mechanism by which rTMS produces relief from depression is still unknown. At a physiological level, the effects of rTMS are frequently reported to be similar to long-term potentiation (LTP) or long-term depression (LTD) of stimulated neurons. This, in turn, implicates changes in synaptic plasticity (that is, the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time in response to increases or decreases in their activity) (Reference Fitzgerald, Fountain and DaskalakisFitzgerald 2006). LTP and LTD are two forms of long-term synaptic plasticity that result in a long-lasting experience-dependent change in the efficacy of synaptic transmission (that is, the amplitude of synaptic potentials). LTP and LTD have been widely studied as they represent cellular correlates of learning and memory (Reference Luscher and MalenkaLuscher 2012). However, invoking this mechanism to explain the effects of rTMS is oversimplistic; further exploration is therefore required (Reference Hoogendam, Ramakers and Di LazzaroHoogendam 2010). A number of studies indicate that large-scale brain networks are altered in patients with depression, and that the degree of the change in the connectivity of these networks predicts the severity of the depression (Reference Salomons, Dunlop and KennedySalomons 2014). Repetitive stimulation of the focal nodes of these networks can result in reorganisation of connectivity patterns in the brain, owing to the brain's inherent plasticity, and use-dependent strengthening of existing pathways (Box 2). Research suggests that rTMS does indeed result in changes in regional brain activity and metabolism, and that applying rTMS at the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) can enhance this region's connectivity with other regions that are crucial for regulating emotional processing (Reference Kito, Fujita and KogaKito 2008).

BOX 2 How rTMS works

-

Stimulates specific regions of the cerebral cortex

-

Possibly improves the efficacy of synaptic transmission

-

Repetitive stimulation of focal nodes of brain networks may result in reorganisation of their connectivity patterns that regulate emotional processing

Clinical guidance and approvals

Worldwide, rTMS is being used as a treatment option for depressive disorders. In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a TMS device for treatment of patients with depression (Reference Horvath, Mathews and DemitrackHorvath 2010). This approval was based on results from one study of patients who had failed to respond to one previous antidepressant. The APA, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP), the British Association of Psychopharmacology (BAP) and organisations in various European countries have discussed the state of the evidence for the efficacy of rTMS in their depression management guidelines and when rTMS might be considered.

In England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued guidance for the use of rTMS, recommending that its use as a treatment for depression should be restricted to research settings until optimal dosing and application parameters are established (NICE 2007). This guidance was reviewed and updated in 2011; however, the recommendation regarding TMS was not changed, owing to lack of evidence. However, in 2012, NHS Evidence reviewed newer research, including a comprehensive systematic review (Reference Allan, Herrmann and EbmeierAllan 2011). They concluded that rTMS may be a therapeutic option for patients with treatment-resistant depression as part of specialist team management. They also highlighted that further research is needed to define optimal treatment protocols. NICE completed a consultation in July 2015 (NICE 2015a). Updated guidance in December 2015 stated that rTMS for depression may be used with normal arrangements for clinical governance and audit (NICE 2015b).

Indications

At present, rTMS is indicated for depression when the patient is responding inadequately to conventional treatments (antidepressant medication, psychological therapy or a combination of these) and when electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) would be the next option.

Real-world data from 42 TMS clinics in North America indicate that the average number of suitable antidepressant treatment trials for a defined episode of depression undergone by patients who receive TMS is 2.6 (s.d. = 2.4) (Reference Dunner, Aaronson and SackeimDunner 2014). A meta-analysis found ECT to be better than rTMS in terms of remission rates (52% v. 34%) and improvement in depressive symptoms, but similar in relation to drop-out rates (Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and DaskalakisBerlim 2013a). The authors suggest that future comparative trials with larger sample sizes, better matching at baseline, longer follow-ups and more intense stimulation protocols are warranted. More recently, another systematic review (Reference Ren, Li and PalaniyappanRen 2014) comparing TMS and ECT concluded that ECT was superior to high-frequency rTMS in terms of response (64.4% v. 48.7%; risk ratio (RR) = 1.41, P = 0.03) and remission (52.9% v. 33.6%; RR = 1.38, P = 0.006), whereas discontinuation was not significantly different between the two treatments (8.3% v. 9.4%; RR = 1.11, P = 0.80). This is essentially the same as the findings of Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and DaskalakisBerlim et al, 2013a,Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and Daskalakisb,Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and Daskalakisc. There are insufficient data to draw any conclusions regarding the long-term efficacy of rTMS. One study has shown that patients with bipolar depression respond less well than those with unipolar depression (Reference Connolly, Helmer and CristanchoConnolly 2012), but there are no studies that specifically focus on the management of bipolar disorder with TMS. In summary, the main indication for TMS treatment is unipolar treatment-resistant depression without psychotic symptoms, especially in patients who do not want to consider ECT (Box 3).

BOX 3 Clinical guidance and approval for rTMS

-

Most guidelines acknowledge a role for rTMS in treating depression, but highlight the lack of robust evidence from large treatment-resistant samples

-

New guidance from NICE in December 2015 states that rTMS for depression may be used with normal arrangements for clinical governance and audit

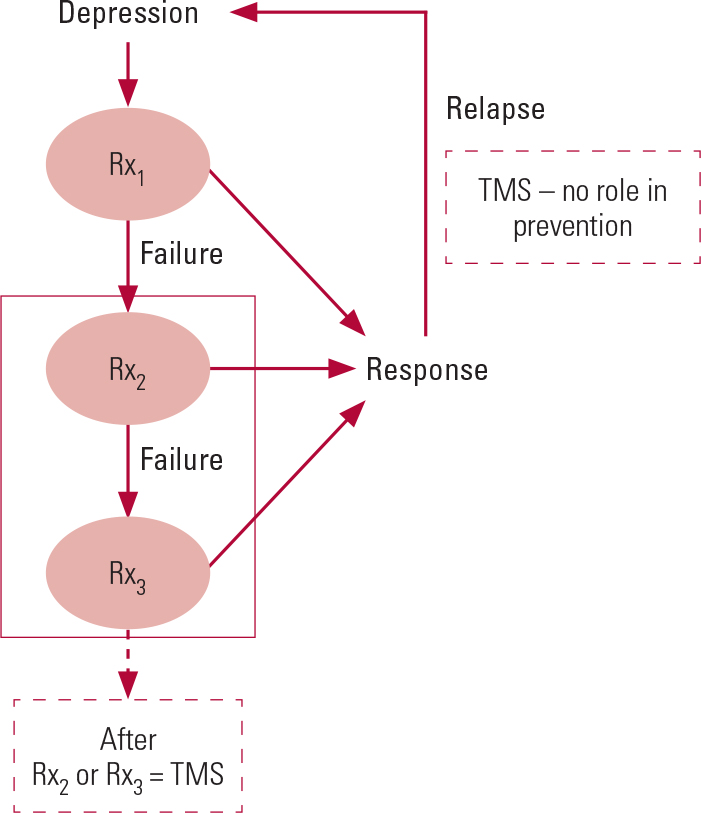

At present, there is almost no evidence for the efficacy of rTMS in relapse prevention in depressive disorder. When using rTMS following a short-term response or remission from depression, it is important to continue optimal evidence-based pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapeutic approaches aimed at preventing further relapses. rTMS, as indicated in Fig. 1, has no role in maintenance treatment for depression.

FIG 1 The place for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in the current depression treatment pathway. TMS may be used if the patient has not responded to two or more trials of antidepressant medication (Rx), but it is not appropriate for maintenance treatment or to prevent relapses.

Contraindications

There are a number of contraindications for rTMS as a treatment for depression. These include:

-

a history of epilepsy or organic brain pathology

-

sleep deprivation

-

acute alcohol-dependence syndrome

-

use of drugs that cause a significant reduction in seizure threshold

-

severe or recent heart disease

-

presence of surgically placed ferromagnetic material such as a cochlear implant or cardiac pacemaker.

However, recent evidence suggests that sleep deprivation need not be considered to be a contraindication (Reference Krstic, Buzad&zcar;ic and MilanovicKrstic 2014; Reference Tang, Li and WangTang 2015). All patients should be screened using a standard questionnaire before being accepted for rTMS treatment.

Patient selection

As part of the process of selecting patients for rTMS, it is important to gain information on the clinical features of past treatment failures (Reference Fitzgerald and DaskalakisFitzgerald 2013). The latest interventional procedure guidance for rTMS in depression (NICE 2015) states that: ‘The Committee was advised that the procedure may not be appropriate for treating some kinds of depression and that patient selection is therefore most important’. At present, most evidence supporting the use of rTMS has been gathered from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving out-patients. These patients had depression of sufficient severity to interfere with daily functioning, but their symptoms were not so severe as to prevent daily attendance on an out-patient basis to receive 2–3 weeks of rTMS treatment. Additionally, although many trials included patients who had failed to respond to at least two antidepressant treatments, the relationship between the degree of treatment resistance and the effectiveness of rTMS continues to be unclear – especially as there is no unanimous, categorical definition of treatment-resistant depression (Reference Mitchell and LooMitchell 2006; Reference SchutterSchutter 2009). rTMS is less effective than ECT in the presence of psychotic depression, although this observation is based on post hoc analyses from only a small number of head-to-head comparisons between the two techniques (Reference Ren, Li and PalaniyappanRen 2014).

Overview of TMS administration

Administration of rTMS is an out-patient procedure and does not require sedation or general anaesthesia. Once the patient is comfortably seated in a chair, a small insulated electromagnetic coil is placed on their scalp. In people with depression, placement of the coil is on the left DLPFC. The patient will have earplugs to mask the noise from the discharging coil. The intensity of rTMS is usually set as a percentage of the patient's motor threshold, which is defined as the minimum stimulus strength required to induce minimal involuntary muscle movements (usually in the hand). Although there are various treatment protocols, the FDA-based standard parameters are the most widely used. These include an intensity of 120% of the patient's motor threshold, with a total of 3000 pulses per session, lasting 37.5 min (4 s of treatment once in every 26 s). Treatment with rTMS usually involves daily sessions 5 days a week for 4–5 weeks and possibly longer (Reference Horvath, Mathews and DemitrackHorvath 2010).

Efficacy

The efficacy of rTMS treatment for major depressive disorder has been well established over recent years, using various different clinical populations as well as differing forms of TMS (high frequency, low frequency and bilateral) (Table 1). Many systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised, double-blind and sham-controlled trials of rTMS for treating major depressive disorder have shown it to be effective as an augmentation therapy or as a monotherapy with a benign tolerability profile (Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and DaskalakisBerlim 2013a,Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and Daskalakisb,Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde and Daskalakisc; Reference Gross, Nakamura and Pascual-LeoneGross 2007; Reference SchutterSchutter 2009). The initial device approval by the FDA was based on a post hoc analysis that focused on patients with one antidepressant trial failure (that is, with a low level of treatment resistance as defined by Reference Thase and RushThase & Rush, 1997). However, meta-analysis of RCTs that specifically focused on patients with more than two antidepressant trial failures (range 3.2–6.5, where data were available) suggests that rTMS produces three times higher short-term response rates when compared with sham treatment and five times higher short-term remission rates (Reference Gaynes, Lloyd and LuxGaynes 2014). At present, it is uncertain how long these benefits last.

TABLE 1 Meta-analytic studies of the antidepressant efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) published in or after 2003a

Durability studies have reported a 13% relapse rate when participants are followed up for 6 months. In one particular study (Reference Janicak, Nahas and LisanbyJanicak 2010), 301 patients with treatment-resistant depression were randomised to active or sham TMS for 6 weeks, followed by a 6-week open-label trial (in which both the researchers and participants knew which treatment was being administered) involving participants who did not respond in the initial study. Participants were followed up while being maintained on protocol-based antidepressant monotherapy, with ‘rescue TMS’ if required. Thirty-eight per cent of participants required rescue TMS for symptom worsening; of these, 84% recovered with the rescue administrations. Overall, 10% relapsed despite this combined TMS and pharmacotherapy approach.

Longitudinal studies with 1-year follow-up data showed a 37% relapse rate among those who initially responded or remitted with acute rTMS treatment (Reference Dunner, Aaronson and SackeimDunner 2014). Sixty-two per cent of the 49 patients who received maintenance rTMS for 6 months after their initial response to acute rTMS treatment continued to maintain their responder status (Reference Connolly, Helmer and CristanchoConnolly 2012). However, owing to the paucity of evidence supporting the long-term efficacy of rTMS, we consider the current evidence to be limited to short-term efficacy and not applicable to relapse prevention (Fig. 1). Approaches such as episodic ‘rescue TMS’ appear promising, but they do not have experimental support at this stage.

Safety

The international scientific community has evaluated the available evidence on the administration of TMS in both clinical and research settings and has developed a safety protocol (Reference Rossi, Hallett and RossiniRossi 2009). The potential side-effects of TMS include seizure induction, transient acute hypomania, syncope, transient headache, neck pain and local discomfort, transient hearing changes and transient cognitive changes. A review of the most recent evidence on rTMS for sensory phenomena concluded that TMS is generally well tolerated by patients (Reference Muller, Pascual-Leone and RotenbergaMuller 2012). A summary of key adverse effects from meta-analysis of rTMS studies is reported by Reference Slotema, Blom and HoekSlotema et al (2010) (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Reported adverse effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)

Patients’ experience of rTMS

Little has been published about patients’ actual experience of rTMS. Reference Rosedale, Lisanby and MalaspinaRosedale et al (2009) conducted a phenomenological study and found that a certain mindfulness emerged during the treatment process. Participants reported being conscious of what they were thinking, and they began to imagine themselves in different situations with new possibilities being realised. The participants in this study ‘consistently reinforced that connection with the clinician influenced treatment experience, completion, and depression outcomes’. They reported that their relationship with the clinician was strengthened when time was allotted to discuss the mechanism of TMS, to explain stimulus placement, to show concern about comfort and clinical response, and to demonstrate interest in the participant's ongoing life; and also when the clinician was available for emergencies between sessions.

Availability of TMS in the NHS

At present, TMS units are being set up in many National Health Service (NHS) trusts. TMS clinics are already in operation in Nottingham (supported by Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust), Northampton (supported by Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust) and Grimsby (supported by NAVIGO, the local mental healthcare provider). TMS treatment for depression can also be obtained from several private providers, especially in London. Figure 1 illustrates the place for TMS in the current depression treatment pathway. This pathway contrasts with most of the rTMS studies, which have typically been carried out in people who have failed to respond to only one antidepressant treatment trial.

Conclusions

Neuromodulation is an emerging new therapeutic field for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions. During the past decade, TMS has been used widely for the treatment of depression and is now an established, safe and effective option for treatment-resistant depression. There is a need for large, well-conducted, longer-term RCTs of TMS in populations of patients who have failed to respond to three or four antidepressants and psychological therapies, in addition to pragmatic evaluation of its utility in the less treatment-resistant populations in which most RCTs have been conducted to date.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 According to the most recent NICE guidance for rTMS in depression:

-

a rTMS can be used for any type of depression

-

b rTMS should not be combined with pharmacotherapy

-

c rTMS is best used as an adjunct to ECT

-

d rTMS has adequate evidence regarding safety and short-term efficacy

-

e rTMS should only be used in research settings.

-

-

2 The most likely mechanism by which rTMS works in the treatment of depression is:

-

a providing regular contact with a healthcare professional

-

b directly stimulating areas of the brain relevant to depression

-

c inducing involuntary muscle movements

-

d improving sleep

-

e stimulating neurons to become stronger.

-

-

3 A contraindication for rTMS as a treatment for depression is:

-

a pregnancy

-

b presence of metal fillings

-

c presence of a cochlear implant

-

d asthma

-

e diabetes.

-

-

4 The administration of TMS requires expertise in:

-

a neuroanatomy

-

b anaesthetic administration

-

c interpretation of EEG

-

d interpretation of ECG

-

e estimating motor threshold.

-

-

5 A common side-effect of rTMS is:

-

a joint pain

-

b neck pain

-

c blurred vision

-

d unusual behavior

-

e tiredness.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | b | 3 | c | 4 | e | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.