CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Highly frequent users of the emergency department (ED) present with an increased prevalence of chronic disease, mental health, and substance misuse.

What did this study ask?

What is the proportion and demographic and medical characteristics of high frequent users with chronic pain visiting an ED.

What did this study find?

This chart review found 38% of high frequent users (≥12 visits) presented with chronic pain to the ED.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Treating high frequency ED users with chronic pain requires consideration of their comorbidities and psychosocial needs for best clinical outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals who repeatedly present to the emergency department (ED) require substantial medical resourcesReference Byrne, Murphy and Plunkett1,Reference Blank, Li and Henneman2 and are increasingly the focus of programmingReference Niska, Bhuiya and Xu3–Reference Soril, Leggett, Lorenzetti, Noseworthy and Clement5 to reduce ED overcrowding and wait times.6 Pain has been reported as the reason for presentation to the ED for 38%–78% of all ED visits, with chronic pain accounting for 10%–16% of visits.Reference Todd, Cowan, Kelly and Homel7–Reference Small, Shergill and Tremblay9 The highest standard of care for chronic pain involves a longitudinal and interdisciplinary approach along with self-management efforts, similar to other chronic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Reference Hillas, Perlikos, Tsiligianni and Tzanakis10 and diabetes mellitus.Reference Nathan, Poulin and Wozny11 Given the episodic nature of ED care, it is not an appropriate setting for chronic pain management.

There are large variations in the definitions of high frequency ED users, ranging from 2 visitsReference Hunt, Weber, Showstack, Colby and Callaham12 to as many as 20 visitsReference Oliveira13 per year, with four or five visits being the most common criteria. Among high frequency users, older age, low socioeconomic status, chronic comorbidities, and high disease burden correlate with increased ED visits.Reference Pines, Asplin and Kaji14 Multiple ED visits are associated with greater utilization of other forms of health care, suggestive of unmet health care needs.Reference Maeng, Hao and Bulger15 Previous attempts to better understand pain-related ED presentations have yielded conflicting results because of variations in the population, methodology, and pain problem of interest.Reference Cordell, Keene and Giles16–Reference Edwards, Moric, Husfeldt, Buvanendran and Ivankovich19 This literature may also not reflect current circumstances, in which increased opioid-related morbidity and mortality are motivating changes in the way pain is managed.Reference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin20 In a recent review, Pines stressed the importance of understanding high frequency users with specific conditions better to guide the development of targeted interventions.Reference Pines, Asplin and Kaji14,Reference LaCalle and Rabin21

This study is part of a program of research investigating the frequent use of the ED by patients who present for chronic pain with the goal of developing cost-effective interventions and improving patient care.Reference Poulin, Nelli and Tremblay22,Reference Rash, Poulin and Shergill23 The objectives of this study were to: 1) determine the proportion of highly frequent ED users who were presenting for chronic pain; and 2) describe the demographic and medical characteristics of patients with chronic pain.

METHODS

Study design and time period

This was a cross-sectional study consisting of a health record review of high frequency users from April 1, 2012, to March 31, 2013. This study was approved by the institutional research ethics board.

Setting

The study was conducted at an urban tertiary care academic medical centre in Canada. There were 148,778 ED visits during the 2012–2013 fiscal year, including 22,995 Canadian Triage and Acuity ScaleReference Bullard, Musgrave and Warren24 (CTAS) category 4 (less urgent condition) and 3,462 Category 5 (non-urgent condition) visits.

Population

To be included, patients had to 1) be ≥18 years of age; and 2) have had ≥12 ED visits during the study period.Reference Kim, Kwok, Cook and Calder4,Reference Jambunathan, Chappy, Siebers and Deda25 Because of resource limitations, we focused on highly frequent users with 12 or more visits in preparation for piloting a small collaborative care program. Patients who had 50% or more of their ED visits attributed to chronic pain were classified as high frequency users because of chronic pain; all others were classified as non-chronic-pain high-frequency users. Chronic pain is defined as recurrent or persistent pain lasting for more than three to six months or beyond the normal duration of healing.Reference Merskey and Bogduk26 Pain could be constant (e.g., low back pain and fibromyalgia) or recurrent (e.g., migraine and nephrolithiasis).

Procedures

We obtained the list of patients with ≥12 ED visits during the 2012-2013 fiscal year from the hospital administrative database. All available demographic information, ED utilization, and medical history including specialist consultation notes were reviewed independently by two paired reviewers with expertise in chronic pain (two anesthesiology residents, one chiropractor, and one staff anesthesiologist with expertise in pain medicine) who attended training and pilot tested their review skills with 10 charts. Each ED visit was classified as either “chronic pain” or “not chronic pain related” using the definition above, along with additional information in Figure 1. Disagreements were resolved through consensus meetings. The following data were collected in duplicate by two reviewers using a standardized abstraction form (Excel Version 2013): age, gender, total number of ED visits, total number of and total length of stay for in-patient admissions, use of opioid medication, current and past substance abuse, mental health, and other medical conditions, as well as most responsible diagnosis for the majority of ED visits. For patients visiting repeatedly for chronic pain, we collected this additional data: location of pain and type of pain.

Figure 1. Criteria to classify an ED visit as being chronic pain related (both A and B must be satisfied).

Statistical analysis

Data were transferred into SPSS 23.0 for analyses.27 Descriptive and univariate analyses were performed. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs), and categorical variables are presented as percentages and counts. Demographic variables (age, gender) and ED visit variables (number of visits to the ED, having a general practitioner, number of in-patient admissions during the study period, and length of stay for each admission) were compared between the non-chronic-pain high-frequency users and chronic-pain high-frequency users using t-tests and chi-square tests. Given the exploratory nature of this work, no corrections were applied to adjust for inflation in familywise error because of multiple statistical tests.

Sample size

Our sample size was restricted based on our definition of high frequency users. A sensitivity analysis was performed using GPower 3.1.9.2 (2019) to evaluate the magnitude of effect size that could be detected between chronic-pain high-frequency users and non-chronic-pain high-frequency users. Using two-tailed hypothesis testing with α of 0.05 and power set to 80%, a sample of 247 patients was sufficiently sensitive to detect an effect size that met or exceeded d of 0.36, representing a small to medium effect size by Cohen's standards. For proportional differences, the sample was sufficient to detect an effect that exceeded χ2(1) critical of 3.84.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

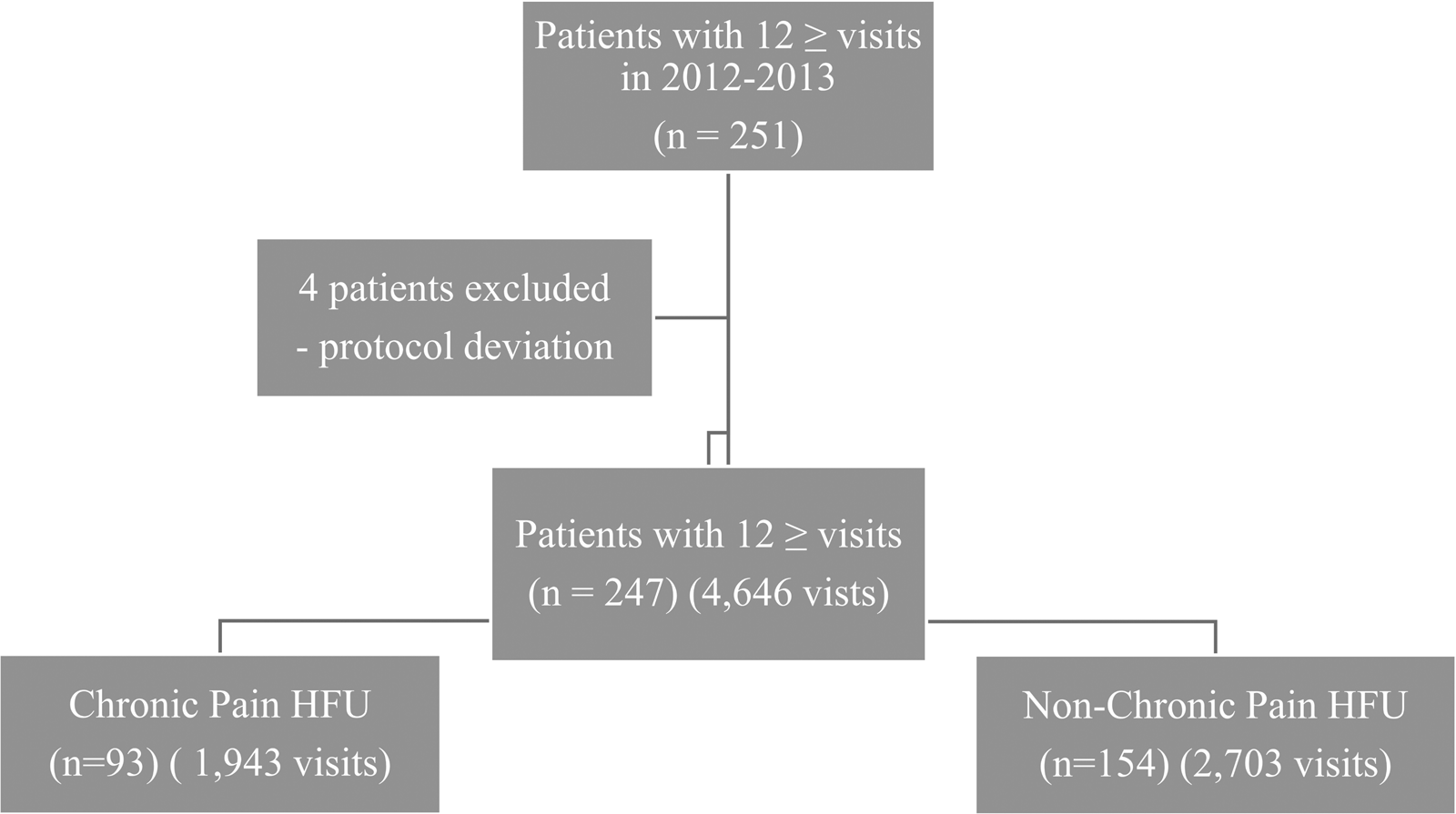

There were 251 patients who had ≥12 visits to the ED during the 2012–2013 fiscal year. Four patients who were 17 years of age were excluded from the final dataset, which consisted of 247 patients (50.2% female, mean age 47.2, SD = 17.8 years old) accounting for 4,646 ED visits (Figure 2). Patients in this group were among the top 1% of users, accounting for 3.1% of all ED visits and 17.8% of all CTAS category 4 (less urgent conditions) or 5 (non-urgent conditions) visits. The majority (75.7%) had a family physician. The top three reasons for ED presentation for the entire high frequency user group were chronic pain (37.7%), alcohol abuse (8.5%), and cellulitis (6.0%). The top ten most common diagnoses are listed in Table 1. Mental health issues and substance abuse were commonly documented in the medical history: 52.6% of high frequency users reported mental health issues, with depression being the most common; and 42.1% reported a history of substance misuse, with alcohol misuse being the most common.

Figure 2. Study flow diagram.

Table 1. Top ten most responsible diagnoses for repeated presentation

Note: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; UTI = urinary tract infection.

*n = 156 pertains to 156 participants represented in the top 10 most common diagnoses. The remaining 91 participants did not present with these diagnoses.

†Substance abuse includes opioid, cocaine, tetrahydrocannabinol, benzodiazepines, stimulants, polysubstance abuse, lithium, intravenous (IV) drugs, anticholinergics, gravol, ecstasy, and muscle relaxants.

Comparison between chronic-pain high-frequency users and non-chronic-pain high-frequency users

Table 2 lists the demographic and medical characteristics, as well as health care utilization data for both chronic-pain and non-chronic-pain high-frequency users. There were 93 patients with ≥12 visits (1,943 total ED visits) for high frequency users with chronic pain and 154 patients for high frequency users without chronic pain (2,703 total ED visits). No age difference was detected between groups, but women were overrepresented among high frequency users with chronic pain (64.5% v. 41.6%, respectively). Both groups had a similar proportion of patients rostered to a family physician (high frequency users with chronic pain = 80.6%, and high frequency users without chronic pain = 73.3%). The high frequency users with chronic pain had significantly more ED visits (mean = 20.89, SD = 12.1) than the non-chronic-pain group (mean= 17.6, SD = 7.5), with a small to medium effect size (d) of 0.32. There was a non-significant trend toward a greater number of in-patient admissions for high frequency users with chronic pain, but no difference in in-patient length of stay. There were no differences between the two groups in the proportion of patients with a documented comorbid medical condition, but more patients in the chronic-pain high-frequency user group had documented hypertension (32.3% v. 20.8% for non-chronic-pain high frequency users). More patients in the chronic-pain high-frequency group were currently prescribed an opioid than in the non-chronic-pain high-frequency user group (52.7% v. 19.5% for non-chronic-pain high-frequency users).

Table 2. Demographic, ED utilization, and medical history characteristics

Note. BZD = benzodiazepine; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED = emergency department; EtOH = ethyl alcohol; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

Other abuse includes stimulants, polysubstance abuse, lithium, intravenous (IV) drugs, anticholinergics, gravol, ecstasy, and muscle relaxants.

Other medical includes, but not limited to, sleep apnea, pulmonary embolus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, pneumonia, Alzheimer's dementia, and cerebral palsy

*Significance at the 0.05 level

There was no difference in the proportion of patients with a documented mental health history between the two groups. There was a non-significant trend suggesting that substance misuse problems were more frequent in the non-chronic-pain group. Both groups reported similar opioid misuse history; however, a history of alcohol, cocaine, and tetrahydrocannabinol misuse was more often reported for non-chronic-pain high-frequency users than the chronic-pain high-frequency users (see Table 2).

Chronic pain–related complaints among high frequent users with chronic pain

Abdominal pain was the most common presenting concern among high frequency users with chronic pain (54.8%). Chest pain (10.8%) or pain in multiple areas (11.8%) was also common (see Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the proportion and characteristics of high frequency users visiting the ED for chronic pain in Canada. We found that 37.7% of high frequency users visited the study site for chronic pain. High frequency users with chronic pain visited the ED more often than those without, and their visits accounted for 17.6% of all CTAS category 4 and 5 ED visits during the 2012–2013 year. Comparatively, in a separate review of 1,000 charts selected at random, 10% of all ED visits were attributable to chronic pain at this institution over the same time period.Reference Small, Shergill and Tremblay9 There was also a non-significant trend for individuals with chronic pain to be admitted to in-patient care more often. This may reflect a higher level of distress being communicated in the setting of chronic pain and demonstrates the pressure that unmanaged chronic pain exerts on acute care resources.

More than one-half (55%) of all chronic pain visits in our sample were driven by abdominal pain; this confirms the findings of Kim et al. who indicated that abdominal pain was the most common reason for consultation among patients with seven or more ED visits per year in a Canadian hospital.Reference Kim, Kwok, Cook and Calder4 Pain in the abdomen can arise from several organ systems including genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and gynecological tracts, but in many cases, no organic causes for the pain could be identified.Reference Ringel-Kulka and Ringel28 Patients without a diagnosis can be driven to visit the ED in the hope of being able to access advanced diagnostic tests.Reference Glynn, Brule and Kenny29 Even in the presence of a clear diagnosis, problems such as endometriosis and Crohn's diseaseReference Yantiss and Odze30 can be difficult to manage because of their chronicity and episodic nature. Many patients visit the ED after having exhausted self-management strategies.Reference Poulin, Nelli and Tremblay22 This highlights the importance of assisting patients in developing effective strategies to avoid and manage acute flare-ups.

Unsurprisingly, high frequency users with chronic pain were more likely to be using prescription opioids than users without chronic pain. This is in line with current guidelines recommending that opioids be trialled in the context of persistent pain that is refractory to other forms of pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological therapies.Reference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin20 However, the benefits of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain are generally small,Reference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin20 and side effects can include hyperalgesiaReference Velayudhan, Bellingham and Morley-Forster31 and the development of an opioid use disorder.Reference Phillips, Ford and Bonnie32 Significantly fewer individuals with chronic pain had a documented current or past history of a substance misuse problem in comparison with non-chronic-pain users. This aligned with studies indicating that less than 5% of patients prescribed opioidsReference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin20 develop a substance use problem, but it could also be indicative of the difficulty teasing out the problematic use of opioids in the context of chronic pain.

More than one-half of the high frequency users in this sample presented with a current or past history of mental health problems in line with previous research investigating factors associated with ED use.Reference Kim, Kwok, Cook and Calder4,Reference Hunt, Weber, Showstack, Colby and Callaham33,Reference Choinière, Dion and Peng34 Chronic pain is generally best managed using a biopsychosocial approach that combines patient education and physical and psychological therapies, along with pharmacotherapy and attention to social determinants of health.Reference Cheatle35 In a pilot study, Rash et al. (2018) enrolled high frequency users with chronic pain into an interdisciplinary chronic pain program that developed and implemented personalized care plans. Results indicated an improvement in clinically important outcomes and ED visits. ED physicians reported that these plans were particularly helpful when meeting with patients during subsequent ED visits.Reference Cherner, Ecker, Louw, Aubry, Poulin and Smyth36

A lack of access to primary care is often cited as a reason for ED visits; however, the majority of high frequency users with chronic pain had access to a family practitioner. This supports research demonstrating that patients who frequently use the ED also rely on primary care.Reference Palmer, Leblanc-Duchin, Murray and Atkinson37 An important consideration, however, is the difference between a patient being rostered to a family physician and a patient's perception that they can access help from their primary care providers.Reference MacKichan, Brangan and Wye38 In Canada, barriers such as significant primary care wait timesReference Ansell, Crispo, Simard and Bjerre39 and limited availability of same-day appointments can result in increased presentation to urgent care for non-urgent health concerns.

The primary limitation of this study was that data collection focused on one Canadian hospital that could impact the generalizability of results. There are also inherent limitations to using a chart review design as this relies on extracting data that were collected for alternative purposes than for a research study. It is not possible to ascertain if the documentation of the chart review data was complete or accurate. The extraction of data also relies on chart reviewers; in this study, each of the reviewers was affiliated with an academic pain clinic operating within the hospital in which the study was conducted. It is possible that this could have biased the review toward identifying more visits because of chronic pain as the extractors were aware of the study objective. This is unlikely, however, as the data extraction process involved consensus meetings to obtain agreement from other reviewers.

Our work highlights differences between high frequency users with and without chronic pain to guide the development of targeted interventions. We also found that the two groups were similar in many ways (e.g., admissions, mental health concerns, and medical comorbidity). Future research that investigates other factors may help to differentiate high frequency users with chronic pain (e.g., social support and disability) better and guide intervention development.

CONCLUSIONS

Unmanaged chronic pain contributes to a significant proportion of acute health care resource utilization. Patients with chronic pain using the ED frequently present with multiple medical and psychosocial challenges including chronic use of opioid therapy. The treatment of chronic pain in the ED, as well as easy-to-access alternatives to support patients and their health care providers, need to be part of a cohesive approach to reduce ED use and improve the quality of life of people living with chronic pain who frequently use the ED. This could be an important aspect of an eventual Canadian Pain Strategy.Reference Kelly40

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by funding from the Chronic Pain Network. The authors would like to acknowledge the following people for their meaningful contribution to this study: Heather Romanow, Eve-Ling Khoo, Melissa Milc, and Emily Tennant.

Competing interests

None declared.