The data collection of […] overseas varieties of pidginized and creolized forms of German is still in its infancy. Some fieldwork could still be carried out but time for linguistic rescue work is running out rapidly (Mühlhäusler Reference Mühlhäusler1984:56). Ich bin Duitse vrouw. Alte Duitse vrouwe sei. Viele Duitse leute gearbeiten (Petrina, Swakopmund 2000). Footnote 1

1. Introduction: Blind Spots

Apart from Mühlhäusler's (Reference Mühlhäusler, , Auburger and Heinz1979, Reference Mühlhäusler1983, Reference Mühlhäusler1984) work on Pidgin German in New Guinea and Kiautschou, Volker's (Reference Volker1982, Reference Volker1989, Reference Volker1991) publications on Rabaul Creole German (Unserdeutsch, ‘Our German’), and more recently Engelberg (Reference Engelberg, , Schulze, James, David, Grit and Sebastian2008), there has been little interest in the investigation of German-based contact varieties in the former German colonies. The silence becomes absolute when one looks at the African colonies: Togo, Cameroon, German East Africa (present-day Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda), and German South West Africa (present-day Namibia). What was the linguistic impact of German colonial rule on the African continent?

Namibia was by far the most important overseas territory for the development of German-based contact varieties. It was Germany's only settler colony, and exposure to German thus extended beyond schools, mission stations and the occasional contact with colonial administrators. Employment relationships in particular created opportunities for informal/untutored language acquisition which continued beyond Germany's official reign: many German settlers remained in the territory after World War I and their descendents continued to form an economically and politically influential, as well as privileged, minority within Namibian society throughout the 20th century.

This longstanding and intense contact situation notwithstanding, linguists have generally argued that the German settlement had little impact on local linguistic repertoires. Thus, Maho (Reference Maho1998:170) states in his overview of Namibia's languages: “the German language does not seem to have spread much outside of the German descendant population.” Shah (Reference Shah2007:21) notes that German remained the language of a privileged white minority with only “few Blacks” speaking German (also Gretschel Reference Gretschel and Martin1995), and Owens (Reference Owens2008:236) described non-matrilectal German in Namibia as structurally and functionally highly restricted:Footnote 2

In businesses run or heavily patronized by ethnic Germans, one had for decades encountered black employees speaking an accented, functional German with unstable, Afrikaans-influenced grammar, and a vocabulary largely limited to the dealings in that business. […]. Blacks with broad, nuanced linguistic competence in German were rare.

While forms of non-native German have certainly been around “for decades” and show varying levels of interference from Afrikaans (an important L2 in Namibia), the vocabulary and proficiency of many of its speakers clearly exceeds “the dealings in that business.” This is not to say that what is locally known as Kundendeutsch (‘customer German’) does not exist. However, non-native German in Namibia cannot be reduced to such varieties, which consist of little more than a few stock phrases and vocabulary items.

Of the over 120 speakers interviewed for this study, all were able to discuss a wide range of topics in German during in-depth sociolinguistic interviews. Their competence, while showing structural reduction as well as contact-based innovations, was sufficiently “broad” and “nuanced” to narrate their life and family histories, to discuss politics and social change, to tell African folk tales, and to explain a wide range of cultural practices, ranging from dress to food, from wedding ceremonies to initiation rites. Why did these competencies remain invisible in the literature on German in Namibia?

Nora Schimming-Chase, Namibia's former ambassador to Berlin, highlights in her critical epilogue to Wentenschuh's Reference Schimming-Chase and Walter1995 photographic essay—Namibia's Germans. History and Present of the German Language Community in the South-West of Africa—how German-speaking Namibians of non-European origin were marginalized and “silenced” in traditional accounts of the German speech community in Namibia:

Who are the “Germans” in Namibia? Those Namibians who speak German as their mother tongue? Those who have German ancestry, or only those with German ancestry and white skin? Or does this include everyone who, because of their own wish or our history, adopted German […]? The author [Wentenschuh] refers to Black Namibians of German ancestry only once. This is significant as it is (almost) a continuation of an old habit to ignore their existence. However, we must applaud him for mentioning them at all (p. 270).Footnote 3

Whether of mixed parentage or “purely African,” the colonial project consistently constructed indigenous populations as “the other,” and expressed strong disdain for so-called “trousered Africans” who adopted and appropriated cultural and/or linguistic aspects of colonial culture (Spear Reference Deumert2003). Thomas (Reference Thomas1994) has argued that relics of these attitudes are still with us and create “blind spots” in our academic vision. They focus our attention on what is considered “truly African” (or “indigenous”), thus ultimately denigrating and marginalizing those new social and linguistic practices and repertoires that emerged across Africa as a result of the colonial experience.

The complex sociolinguistic competencies speakers displayed in the interviews do not show themselves easily in inter-ethnic social contexts such as workplaces, which were the only places were Africans and Europeans interacted on a regular basis. The overt power relationships of such spaces led to limited conversational interaction and the disenfranchised remained invisible to those who commanded power and prestige in the colonial society. In several cases employers of those I had interviewed were ignorant of their employees’ linguistic skills, referring to their abilities dismissively as ja, ein paar deutsche Worte (‘yes, a few German words’). Such misconceptions on the side of employers are, however, only partially a result of the, often limited, communicative demands of the work contexts and the pervasive ideologies of colonial thinking: some participants would deliberately underplay their linguistic skills as it meant that employers would talk more freely in front of the staff who could obtain potentially important information this way. This paper seeks to document these hidden language skills.

Several speakers referred to their variety of German as Kiche Duits, that is, Küchendeutsch (“kitchen German”), showing loss of rounding in the front vowel [y] > [i] and using the Afrikaans pronunciation for “German.”Footnote 4 Speakers of Kiche Duits (often shortened to Duits) came from different language groups, primarily Otjiherero and Khoekhoe, and the majority were born in the 1920s and 1930s; the youngest speakers in the 1950s. Younger Namibians, who had the advantage of an improved school system that gave them formal access to Afrikaans and English, tend to prefer these languages for interethnic communication. This development was supported by the increasing multilingualism of matrilectal German speakers and the general shift toward English after Namibia's independence. Older members of the German community, on the other hand, were (and are) often monolingual and insisted on the use of German within their houses, businesses or workshops. This made the acquisition of German a necessity for their workers. Kiche Duits is a marginal language in the sense of Reinecke (Reference Reinecke1937), and today a dying contact variety (on contact languages and language endangerment, see Garrett Reference Garrett2006).

In this paper I present the first historical and sociolinguistic overview of Kiche Duits. Sections 2–4 reconstruct the historical background. Section 5 outlines the fieldwork that was conducted in 2000. Section 6 describes contexts of acquisition. Sections 7 and 8 look at various aspects of post-colonial “crossing” in Namibia; that is, the sometimes playful and always socio-symbolically meaningful appropriation of linguistic and cultural out-group practices. Section 9 provides an overview of salient linguistic structures and innovations. The final section (10) situates Namibian Küchendeutsch within current debates on contact languages, addressing the perennial question of whether one should now report the “discovery” of a “new” German pidgin language.

2. Namibia: A Historical Overview

With a territory of over 800,000 square kilometers and a population of just over 1.8 million (2001 Census), Namibia is a sparsely populated country. Information on Namibia's pre-colonial history is scarce. The oldest inhabitants of Southern Africa were groups of hunter-gatherers, the so-called San communities (Bushmen in older texts). During the last centuries of the first millennium BCE pastoralist Khoekhoe communities (Hottentots in older texts) moved southwards from Northern Botswana, and some of these groups eventually settled in southern and central Namibia. The languages spoken by these two groups are referred to as Khoesan. However, they do not form a genetic-linguistic entity in the sense of, for example, Indo-European or (Ba)Ntu.Footnote 5 Instead, these languages are believed to constitute a linguistic area, that is, similarities between them are the result of large-scale diffusion processes rather than genetic relatedness (Güldemann & Vossen Reference Güldemann, Rainer, , Heine and Derek2000). In Namibia, Khoesan languages are spoken by groups such as the Namadama (Nama/Damara) and Oorlams (Haacke et al. Reference Haacke, Eliphas, Levi, Wilfrid and Edward1997; Maho Reference Maho1998:103f.).

Ntu-speaking groups entered Namibia during the 17th century from the north and soon established themselves in the northwestern and central parts of the country. Speakers of Oshiwambo and Otjiherero are pastoralists, while groups in the Caprivi area (for example, speakers of Rukawango and Silozi) depend on agriculture and fishing.

From the beginning of the 19th century so-called Oorlam groups entered Namibia from the northwestern Cape (South Africa). The Oorlams were of mixed origin, consisting of (Cape) Khoekhoe, descendants of mixed settler-slave/settler-Khoekhoe unions, runaway slaves and Cape outlaws. These communities were bilingual (Cape Dutch/Afrikaans and Khoekhoe) and settled primarily in southern and central Namibia, where they intermarried with local Khoesan-speaking communities.Footnote 6 Another group of mixed European-Khoekhoe ancestry that entered from South Africa were the Rehoboth Basters who settled in Namibia in the 1870s.

European colonization began in the early 19th century when traders and missionaries entered the territory of present-day Namibia. In 1878 the British Cape Government annexed the area of Walvis Bay, and the rest of the coastal region was purchased by the German trader Adolf Lüderitz from the local Nama chief Joseph Fredericks for one hundred pound sterling and 200 rifles in 1883 (Gründer Reference Gründer1991:80). In 1884, the German Reich took over Lüderitz's possessions, granted the land the status of a protectorate, and began to expand inland.

Increasing tension between German officials and the Ovaherero culminated in the outbreak of military conflict in January 1904 (the so-called “Herero-German War”).Footnote 7 The Ovaherero were defeated at the Waterberg in August 1904 and driven—following an extermination order of General van Trotha—into the Omaheke, a desert-like area where many died of starvation. The survivors were sent either to prisoner of war camps, or to the uninhabitable Shark Island near Lüderitz. Many more died. Oorlam and Namadama groups joined the struggle against colonial rule in 1905 and the war ended in 1908 with the defeat of these groups. About 80% of Ovaherero and between 35 and 50% of Oorlam and Namadama died in the war (Bley Reference Bley1996:150f.). As noted by Jamfa (Reference Jamfa, , Gibney, Rhoda, Jean-Marc and Niklaus2008:202), it was a “war of extermination, designed to annihilate,” and the war is today considered a case of genocide (Cooper Reference Cooper2006).Footnote 8

Germany lost its colonial possessions after WWI, and from 1920 onward South Africa administered Namibia under a C-class mandate (granted by the League of Nations). After WWII South Africa refused UN requests to place Namibia under a trustee agreement, and instead implemented its own apartheid legislation in the mandated territory. A national liberation movement emerged in the 1950s, SWAPO (South West African People's Organization). In 1966 when South Africa ignored the UNs decision to revoke the South African mandate for Namibia, SWAPO began with guerilla attacks from the north. The struggle for independence intensified in the 1970s, and in 1978 resolution 435 was passed by the UN Security Council, containing a detailed plan for Namibian independence. Resolution 435 was finally implemented in 1989, and Namibia declared its independence on March 21, 1990, “after twenty-nine years of German colonial rule and a further seventy-five years of South African occupation” (Silvester Reference Silvester, , Elkins and Susan2005:271).

3. Matrilectal German in Namibia

German settlers arrived in Namibia from the 1890s onwards (Rohrbach Reference Rohrbach1907:245). The early settlers originated mostly from the East Low German dialect area and came from the social and economic fringe of German society (see also Deutsche Kolonialzeitung 1890:96).

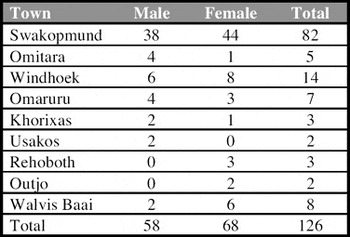

Until about 1900 English- and Cape Dutch/Afrikaans-speaking farmers from South Africa constituted an important group among the colonial population. The presence of “non-German elements” prompted the Reich to embark on a deliberate settlement policy, and the German-speaking population increased by over 300% between 1903 and 1913 (see table 1, and also Walthers Reference Walthers2002:10). Settlement concentrated largely on the southern and central regions of the country, while the northern region (“Ovamboland”) remained under indirect rule.

Table 1. German colonists in Namibia (Oelhafen Reference Oelhafen1926:110–111).

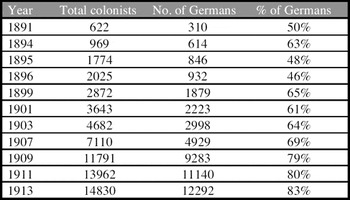

The number of German speakers dropped to about 8,000 after WWI when all colonial government employees were repatriated following Germany's loss of its colonial possessions. However, by 1936 the community had grown again to between 9,000 and 12,000 (Hintrager Reference Hintrager1939). German-medium schools continued to exist under South African rule and German could still be used in dealings with the new admini-stration (protected by the 1923 London Agreement between Germany and South Africa). In 1984 German was officially recognized as the third official language within the administration for Whites. Upon independence in 1990, English was declared as the national and official language of the country (see Harlech-Jones Reference Harlech-Jones1990, Beck Reference Beck, Martin, Joshua and JoAnne2006). Today, the German-speaking population is just under 20,000 (2001 Census, see table 2).

Table 2. Languages groups in Namibia (Census 2001).

Their minority status notwithstanding, German speakers have always been highly visible and influential in Namibia, especially within the urban environment. Thus, when the American consul to South Africa visited Namibia in 1939, he noted:

Although Germans as a whole constitute only a third of the [White] population, they are as individuals very active and enterprising and occupy positions of economic and social influence in their respective communities out of proportion to their numbers. They are not primarily farmers […] but 65% of trading and professional licenses are held by Germans. Thus it is that (except for the American motor cars everywhere) the general impression given by South West African towns is that they are German settlements. The streets have German names and are lined with German shops and stores. The hotels and pensions are German and serve German food and in the cafes German beer (locally brewed) is consumed by persons comfortably reading German newspapers. In Windhoek, for instance, the only daily paper is the German “Allgemeine Zeitung,” while the English paper, the “Windhoek Advertiser” and the local Afrikaans paper appear twice a week only […] in general the languages of the territory are Afrikaans in the country and German in the urban districts […]. I myself spoke German almost entirely while in South West Africa as the simplest means of intercourse (Barron Reference Barron1978:152–153).

Much of this description still applies today, especially in central Namibia (see Silvester Reference Silvester, , Elkins and Susan2005).

For Namibia's close-knit German-speaking minority, language remains a central marker of their distinctive historical identity—an identity that sets them apart from Deutschländers or Dscherries (English “gerry;” Germans from Germany), and which is embodied in the use of a distinct extraterritorial form of German. This variety is commonly called Südwesterdeutsch, henceforth SWD.

Like any other variety, SWD is not homogenous and the frequency with which speakers use SWD variants correlates with age, social status/ education, level of formality, and interlocutors present. Those who have acquired Standard German in the school environment often show conscious avoidance of highly marked SWD features in more formal contexts—especially extensive borrowing from English and Afrikaans. Artisans and farmers have been identified as “typical users” of SWD; the variety is also prominent among the youth and thrives in school hostels, particularly among male speakers (Gretschel Reference Gretschel and Martin1995; see also Brock Reference Brock1990, Mühlhäusler Reference Mühlhäusler1993). Only limited (socio)linguistic research has been carried out to date. Nöckler (Reference Nöckler1963) and Pütz (2001) illustrate salient lexical features of SWD, drawing on written sources as well as “constructed” examples. Brock (Reference Brock1990), Riehl (Reference Riehl2004), and Shah (Reference Shah2007) are more sociolinguistic in orientation and based on spoken language data. Their analyses, however, focus on the description of typical features and do not provide any information on frequencies of usage.

Contact effects are most clearly visible in the lexicon, which shows a high number of borrowings and calques from English and Afrikaans. African languages, which are the majority languages in the country (see table 2), have contributed only a few terms; these include mariva ‘money’ (< ovamariva, Otjiherero) and the adverb huga/huka ‘a long time ago’ (< huga, Khoekhoe), which functions as a temporal emphasis marker (die hat huga lange gegangen ‘she went a very long time ago’). Less common is hakahana ‘quickly’ (< hakahana ‘to hurry’ Otjiherero; for example, die macht nicht hakahana ‘she is not working quickly’).

Grammatical restructuring has been moderate, affecting specific areas of grammar rather than the linguistic system as a whole. Among the features reported in the literature are the following (see Riehl Reference Riehl2004 and Shah Reference Shah2007 for further examples):

morphology

(a) merger of accusative and dative case (occasionally also loss of gender and plural marking in conversational speech, but rare and possibly linked to attrition);

(b) periphrastic possessive (dem Peter sein Auto ‘Peter his car’, also attested in varieties of German);

(c) future tense formation with gehen (‘to go’; in analogy with English/Afrikaans, rather than the standard German future marker werden);

(d) the use of invariant was as a relative marker (< Afrik. wat; German requires the relative pronoun to be marked for gender and case; for example, SWD ein kleines kalb, was ‘a small calf, which’ instead of standard German ein kleines kalb, das [neuter, singular]);

(e) personal pronouns are frequently replaced by definite articles (der kann gut Herero ‘that one [the-masc] speaks Herero well’, rather than er kann gut Herero ‘he speaks Herero well’; also attested in varieties of German).

syntax

(a) loss of verb-final in subordinate clauses after weil (‘because’; in analogy to on-going changes in varieties of German as well as Afrikaans);

(b) non-obligatory use of the conjunction dass (‘that’; possibly due to influence from colloquial varieties of Afrikaans where dat-dropping is common);

(c) changes in negative syntax; that is, in negative sentences with inflected modals and auxiliaries the negative adverb nicht typically precedes the object and occupies the position following the modal/ auxiliary (in line with negation in English and Afrikaans; for example, SWD du musst nicht das sagen ‘you must not say that’ vs. standard German du musst das nicht sagen);

(d) changes in the prepositional phrase, that is, the use of spurious prepositions (such as für in analogy with Afrikaans vir), as well as changes in preposition use (possibly due to interference from Afrikaans and English);

(e) occasional omission of constituents (SWD die Kinder sind in stadt ‘the children are in town’ vs. standard German die Kinder sind in der Stadt; possibly due to interference from English and, in some cases, language attrition).

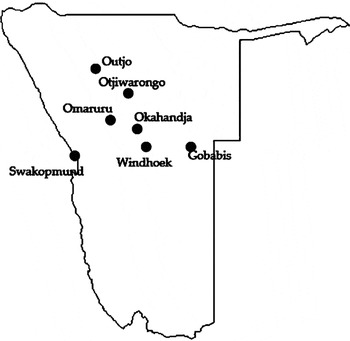

The matrilectal German community, while small in numbers, had a lasting influence in Namibia, especially in the central and central-northern areas where the majority of settlers lived. This includes towns such as Windhoek, Swakopmund, Okahandja, Gobabis, Omaruru, and Otjiwarongo, as well as the surrounding farmland (figure 1). The main indigenous languages are Khoekhoe and Otjiherero; however, Oshi-wambo-speaking contract workers have also migrated into these areas. Afrikaans is the main language for groups of mixed European-African origin.

Figure 1. Central and central-northern Namibia.

4. Historical Evidence: Non-Native German During Colonial Rule

4.1. Acquisition of German I, Acrolectal Varieties

Initial colonization in Africa relied strongly on pre-existing lingua francas: in East Africa there was Kiswahili, in Namibia Cape Dutch/Afrikaans, and varieties of Pidgin English were spoken in Cameroon and Togo. However, from about 1900 the colonial government actively encouraged and supported (via an independent colonial budget) the acquisition and use of German in all its territories (see Mühlhäusler Reference Mühlhäusler1993, and Mühleisen Reference Mühleisen2005, for a discussion of the underlying ideology; see also Sokolowsky Reference Sokolowsky2004).

German was taught as a second language in Namibian mission schools from 1895, and following growing pressure from the colonial government the teaching of German was expanded over the years. The aim was to create “a German-speaking upper class” (eine Deutsch sprechende Oberschicht; Koloniale Rundschau Reference Von König1913) on which the colonial government could draw for administrative purposes. In 1912, von König (pp. 623–624) provided a positive assessment of the situation in Namibia which compared favorably even to the Musterkolonie (‘model colony’) Togo:

Everywhere [that is, in all schools in the colony] special emphasis is put on the acquisition of German […]. The indigenous languages are allowed only as vehicular languages if the teacher needs to explain himself to the students.

According to von König, about 3000 children and adults attended mission schools (including evening classes) at the time of his survey; this constituted about 10% of the estimated indigenous population in central Namibia (using the post-war population estimates given by Gründer Reference Gründer1991:121). Three main groups of pupils were found at the mission schools: (a) members of the African elite, (b) the offspring of inter-ethnic unions, and (c) those who were in the employ of the government or mission, or preparing for such employment. The following overview provides a rough sketch of these three groups of pupils; further research in mission archives is a desideratum.

The African elite

Members of the African elite were generally multilingual, with a solid German mission education and often presented themselves wearing European dress. Margarete von Eckenbrecher (arrived in Namibia in 1902) describes in her memoir Samuel Kariko, the son of the Ovaherero chief in Okombahe (near Omaruru), as follows:

Samuel Kariko was always very distinguished. Once he visited me, in a white suit, with a starched shirt, yellow riding boots, watch, handkerchief and walking stick […]. He spoke German and Dutch well, his English and Namaqua [Khoekhoe] were not bad. He also wrote Herero and Dutch very well, his written German was moderate (1940:119).

Similarly Clara Brockmann (arrived in Namibia in 1907) narrates an encounter with the Khoekhoe Kaptein “Franz” who talked to her using “pure High German” (reines Schriftdeutsch, lit. ‘pure written German’):

He wore clean European dress … [spoke] flawless German. It was the first time that I heard the formal Sie [‘you, formal’] out of the mouth of a native (1912:185).

Children of European/African parentage

As in other colonies, the sex ratio in Namibia was strongly biased toward men. Women made up only about one-fifth of the European population, and intermarriages as well as co-habitation with indigenous women were common among colonists (Oelhafen Reference Oelhafen1926:110–111; Walthers Reference Walthers2002: 34ff.). The main concern of the colonial government was not the existence of sexual encounters as such—many of which were short-lived, exploitative and forced (see Gewald Reference Gewald1999:201–202)—but the children born as a result of such unions. Children of mixed origin were seen as a threat to the colonial order, which was based on a clear-cut legal and social distinction between natives/servants and Europeans/masters. In 1905, the German government forbade any further marriages between Africans and Europeans, and in 1907 the High Court in Windhoek declared all mixed marriages that had taken place before 1905 as null and void. This, however, did not change the reality of such interethnic unions. In 1909 alone 1,574 children were born of mixed parentage (Deutsche Kolonialzeitung 1910:486).

Some mission schools, such as the Augustineum in Okahandja, the Catholic Mission in Windhoek and the orphanage in Keetmanshoop, catered almost exclusively for mixed race children. Hilda, the grand-daughter of a German father and a Khoekhoe-speaking mother, attended the Catholic Mission school in Windhoek in the 1930s and describes a strongly German-dominant school environment (interview 2000 in Swakopmund):

Aber, ehm, aber, und nachher wir bin so nach der schule gegangen, ham wir auch bei die swestern nur, nur Duits gesprechen, wir haben nur Duitse, eigentlich sin wir Duits aufgezogen.

[But, ehm, but, and afterward we went to school, we only spoke German with the sisters, only German, we have only German, actually we were brought up German.]

This is reminiscent of the situation in Papua New Guinea where Unserdeutsch developed in the German-medium (Catholic) mission school environment (Volker Reference Volker1982, Reference Volker1991).

Colonial employees

Among those who received formal instruction in German at mission schools were also indigenous soldiers and policemen, as well as those to be trained as mission school teachers. Pastor Anz of the Lutheran church in Windhoek, for example, ran evening classes that trained indigenous employees for work as interpreters in the colonial administration (Deutsches Kolonialblatt 1902:143). District reports such as the following show that the colonial government succeeded in training local staff with varying levels of competency in German:

Keetmanshoop. The district has good interpreters among the policemen who have been working here for some years. Their knowledge is sufficient for simple translations. In addition, an indigenous teacher who speaks German well is used as an interpreter (Windhoek National Archives, ZBU 249, 18 December 1911).

Bethanien. At our office we have two natives who are able to translate even complex sentences. At the local mission a boy is currently being trained as translator. He will be appointed to the police once he has completed his education (Windhoek National Archives, ZBU 249, 28 November 1911).

4.2. Acquisition of German II, Mesolectal, and Basilectal Varieties

In 1897 rinderpest destroyed the economic base of Otjiherero and Khoehoe-speaking pastoralists. Less than 10% of their herds survived, leading to severe impoverishment of these communities. Many were now forced to sell their labor to the newly arrived colonists or the colonial government in order to obtain food and shelter. This process laid the foundations for a society divided into colonial owners (of land, livestock, etc.) and African non-owners, a new laboring class (Bley Reference Bley1996:124ff.; Werner Reference Werner1998:43ff.; Gewald Reference Gewald1999:110ff.).

Figure 2. Domestic servants: An Omuherero woman serves coffee (Koloniales Bildarchiv no. 009-2071-08).

The increasing proletarization of the African population was actively supported by the colonial government through legislation: lands were confiscated and the right to own cattle was severely restricted; all Africans had to wear passes, and those without labor contracts were prosecuted as “vagrants,” thus effectively creating a system of forced labor (Gründer Reference Gründer1991:122). By 1913 about 95% of the African population in central and southern Namibia was classified as Lohnarbeiter (‘wage laborers’) by the colonial administration;Footnote 9 of these 55% worked as domestic servants or farm workers, 34% in small factories, and 11% in the army or police (Oelhafen Reference Oelhafen1926:116–117; see also figure 2 above).

Colonists and workers did not usually share a common language. Colonial memoirs provide metalinguistic commentary and examples of different communicative responses to this situation. Three main media of inter-ethnic communication are documented in these texts: (a) mixtures of Afrikaans and German, (b) a macaronic Otjiherero-German jargon, and (c) the use of (structurally reduced) non-native forms of German.

Afrikaans-German admixture

Cape Dutch/Afrikaans was brought to Namibia in the nineteenth century when Afrikaans-speaking groups of mixed descent, the Oorlams and later the Rehoboth Basters, migrated from the Cape to southern and central Namibia (see section 2). Structural similarities of Afrikaans and German supported from early on processes of relexification. Examples 1 and 2 come from the memoirs of Margarete von Eckenbrecher (op.cit.) and Ada Cramer (arrived in Namibia in 1906). Afrikaans relexified items are underlined; the sentences were reportedly uttered by Khoekhoe speakers.

(1) Hu kan doch di gnae Frau so afsonderlicke Dinge frag, ons hat die goedgehad.

‘How can Madam ask such strange things, we had the things’ (von Eckenbrecher Reference Eckenbrecher1940:76).Footnote 10

(2) Ossen banja weit hardloop.

‘The oxen ran very far’ (Cramer Reference Höpker, and Will1913:3).Footnote 11

Under South African rule there was increasing dominance of Afrikaans in government, education, and the public domain; the continuing in-migration of White Afrikaans-speaking farmers established the language firmly within agricultural workplaces. Processes of relexification thus continued and mixed language forms are still common today in areas with a high percentage of Afrikaans-speaking Whites.

Extract 3 comes from an interview (2000 Omaruru) with Amon (L1 = Khoekhoe), and shows extensive admixture from Afrikaans. Borrowings from Afrikaans are underlined, syntactic interferences in bold; word-initial /g/ is generally pronounced in line with Afrikaans as [x], not as German [g].

(3) Ich hab da bei Tsumeb gearbeit, daar bei bakkery, daarwaar der brood, arbeiten. Ja, ich hetdaar gelern die Duits. Das is noch alte grootouensdaar bei lokasiewat noch Duits sprechen. Ich habe daar bei brood-hause gearbeit, daar by transporte gearbeit, dort bei Otavi. Toelos ich da die arbeit bei Otavi, dann kryek eine plaase-arbeit, bei eine Duitse, Mr. H., der isoorlede, isnet seine kinder nou bei die plaas, ich arbeit da bei tuin, bei die farm, grunde machen da hinten bei die tuin […] nein, ons lebe nich’ gut, baiehonger hier, das is keine geld, das is nie arbeit in Omaruru nie

‘Then I worked there in Tsumeb, there at the bakery, there where the bread, work. Yes, I have learnt German there. There are still old people there in the location who still speak German. I have worked there at the bread-house, there at the transport, there in Otavi. Then I leave the work in Otavi, then I get farm work, with a German, Mr H, he is dead, it is just his children now at the farm, I work there in the garden, at the farm, making the ground, in the back of the garden […] no, we don't live well, much hunger here, there is no money, there is no work in Omaruru.’

Both Tsumeb and Otavi have a large Afrikaans-speaking population. Heavy lexical borrowing is typical in the local German community, and thus probably formed part of the input. However, matrilectal varieties never show the density of mixture reflected in 3.

Otjiherero-German jargon

Lydia Höpker, who arrived in Namibia in 1913, described the macaronic jargon, a mixture of Otjiherero and German, which was used on her farm as “broken German mixed with bits of Herero” (mit Hererobrocken untermischtes gebrochenes Deutsch; 1997[1936]:13). Examples 4–8 come from her memoirs (1997[1996]), from a short story written by her husband, Carl Höpker (Reference Höpker, and Will1913), as well as the memoir of Hilla von Flotow (1992) who arrived in Namibia in the 1930s, and Cramer's Kinderfarm (Reference Cramer1942).

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

The eye dialect in examples 4–8 shows:

(a) lexical polysemy, for example, in 6 kaputt machen ‘destroy (a thing)’, with the semantic extension ‘to kill (an animate being)’, and in 4 saufen ‘to booze’ meaning ‘to drink’;

(b) grammatical reduplication (in 7 hapuhapu < Otjiherero ehapu ‘swarm’, class 5 noun);

(c) morphological reduction (reduction of Ntu noun class marking, tijruru from otjiruru, mariva from ovamariva; unmarked past tense, sauf);

(d) mixed forms such as kanadji-s < Otjiherero okandu ‘small person’ (class 12 noun) with German default plural -s (and reanalysis of the noun prefix oka- as part of the stem);

(e) use of typical SWD lexical items such as stief (‘very, many’, which is used as an intensifier in SWD; probably North German origin);

(f) omission of constituents (pronouns, articles and VPs).

Evidence for this Otjiherero-German jargon is exclusively of a secondary nature and one might speculate that the same is true for many of such mixed, transient varieties that emerge ad hoc under the pressures of the situation. In those cases where the superstrate (here German) is not withdrawn, these forms are usually replaced by non-native approximations of the superstrate.

Non-native varieties of German

In 1914 Raimund Freiherr von Gleichen published a small booklet, providing those who considered settling in Namibia with practical advice. On the question of language, he remarked:

The colloquial language is the German language. Almost all indigenous people understand German quite well (cited in Mühleisen Reference Mühleisen2005:32).

Descriptions and imitations of non-native varieties of German abound in the colonial literature, gradually replacing forms of “kitchen Herero” used by the colonists. Irle (Reference Irle1911:147, 149) notes:

In the house one just speaks German. People can understand and mostly speak the kitchen German [Küchendeutsch], just as we spoke kitchen Herero in the beginning […]. Earlier the natives [Eingeborenen] laughed about our broken Herero, now we laugh about their German; times are changing.

Lydia Höpker describes in her memoir not only the use of an Otjiherero-German jargon, but also provides glimpses of the non-native varieties of German used by her workers. Example 9 shows omission of NP (determiner) and VP elements (inflected modal; copula) as well as phonological modification (consonant cluster simplification; the addition of word-final vowels in line with Ntu phonology). The use of Afrikaans moi/mooi (‘nice’) is typical for SWD in general; it formed part of the (matrilectal German) input (rather than showing admixture from Afrikaans).

(9) “Judas, why did you take me here?” I snorted after I recovered my spirits a little. “Judas, black sister see! White people but nice!” (Judas, swarze Swestera sehen! Weisse Mense doch moi!) he answered and just couldn't understand why I would rather have spent the night in the bush than with “nice white people” (1997[1936]:41).

Similar examples are reported in Ursula Ewest's (born 1909) locally published memoir Pad (Reference Ewest1999). In example 10 the Khoekhoe-speaking farmhand Klaas uses a reduced form of German with frequent constituent omission (copula, article, auxiliaries). As in example 9 his speech also includes non-standard lexical items which occur in colloquial varieties of SWD: mooi, stief, kant (< Afrikaans, ‘side’), miskien (< Afrikaans, ‘maybe’).

(10) [Context of the episode: The farmer Wolf had recently lost many of his sheep to wild animals and awaits Klaas’ return anxiously]

Klaas welcomed them with a smile. Thank God, it can't be too bad. He brandished his hat and said “Morning, mister” (Morro [Otjiherero greeting], Mister), as if nothing had happened.

“Yes, where have you been this night, how many sheep are missing?,” asked Wolf.

More smiles. “Don't think any. Mister must just count.” (Glaube keins. Mister muss mal zählen)

“But where were you tonight?”

“There, at mountains” (Da, bei Berge), he points vaguely in the direction.

“Why, which mountains?”

The smile disappeared. “Other side of fence. Much grass there. Sheep ate nicely. No wind between high mountains. Sheep slept there” (Andere kant Draht. Stief Gras da. Schafe mooi gefressen. Zwischen hohe Berge doch kein Wind. Schafe da geschlafen.) He looked a little insecure. Wolf was speechless. Klaas misunderstood that and said defensively “No sheep lost, otherwise perhaps many gone” (Kein Schaf verloren, sonst miskien stief weg) (p.90).

Varieties of non-matrilectal German continued to be spoken under the South African mandate. In 1946, the Chief Native Commissioner described the language skills of one Isaak Katjingengue, an Omuherero who worked as a driver for a Mr Feitelberg in Windhoek, as follows:

He [Isaak Katjingengue] speaks the three European languages [Afrikaans, English, German] easily and well, apart from his own language, and can read and write (Windhoek National Archives, A 50/59; June 25, 1946).

And in 1942 Cramer noted:

All Hottentots [Khoekhoe] and Herero in German South West Africa under-stand German and can speak some, and us Germans speak only German with them (p. 19).

Following the 1948 victory of the National Party, South Africa implemented apartheid in the mandated territory, thus continuing and intensifying earlier colonial policies of exploitation and segregation. Contact with German speakers was now restricted entirely to the work environment. Any forms of cohabitation were outlawed under the Immorality Act (1950), and African urban settlements (so-called townships) were moved to the peripheries of towns and cities, far away from White residential areas.Footnote 13 Afrikaans became the dominant language of the new administration, was taught as a second language in the school system, and promoted as a lingua franca for inter-ethnic communication. However, many, especially urban, workplaces remained German-speaking and language learning continued: in the 1970 census over 12,000 Black Namibians reported speaking German (that was 2.1% of the total Black population; 26% indicated knowledge of Afrikaans, and 8% knowledge of English; Kleinz Reference Kleinz1981:267ff.).

5. Fieldwork

The fieldwork was carried out over five months during 2000.Footnote 14 The main fieldsite was the coastal town of Swakopmund, which is colloquially referred to as kleines Deutschland (‘little Germany’). Swakopmund has a high percentage of matrilectal German-speakers, and a carefully maintained German flair: there are German bakeries, cafes and restaurants, the daily Allgemeine Zeitung, German food and beer in the supermarkets, as well as numerous German associations (Gesangsverein ‘choral society’, Schützenverein ‘shooting club’, Kegelverein ‘bowling club’, etc.).

The urban structures of Swakopmund still reflect the rigid boundaries of the apartheid days: the town center, known as die dorp or das Dorf (‘the village’), is almost exclusively White, as is the new residential area of Vineta. Until the late 1950s a mixed Black and Coloured area, referred to as die ou lokasie (‘the old location’) was situated in close vicinity to the town center. In the early 1960s separate residential areas for Black and Coloured people were built in accordance with apartheid legislation at the urban periphery: Black residents were resettled in the new township of Mondesa; Coloured residents were resettled in a separate township called Tamariskia.

Kiche Duits speakers in Swakopmund were reached through local network contacts. According to the ethnographic principle of participant observation I took part in the daily life of the speakers, looked after children, and helped with household duties. I attended the church service on Sundays and was invited to birthdays and weddings. Most of the interviews took place at the houses of those to be interviewed and had the character of a friendly visit—often accompanied by a shared meal—rather than a formal interview. Frequently family members and neighbors participated in the conversation, and several spontaneous group interviews were recorded in that way. Channel cues such as laughter, variation in pace and pitch, etc. also indicate the closeness of the recorded data to natural speech events. In conducting the interviews I generally used a mid-range speech level, but also found myself to engage in linguistic accommodation, including the use of features that I would consider ungrammatical in my native idiolect of German.

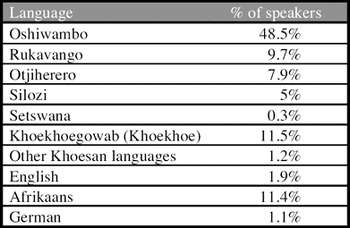

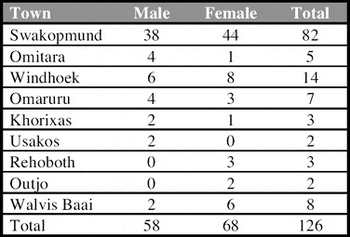

Topics ranged from questions about where and how German was learnt, when and with whom it was used, to family anecdotes, work experiences and gossip about employers, life under apartheid, the differences between life on the farms and in town, sociopolitical change, as well as the description of indigenous practices and customs, and the narration of traditional African folk tales. In addition, speakers were asked to repeat some of the sentences that were used by Georg Wenker in his 19th century survey of German dialects (to test for phonetic features) and to translate a few sentences from Afrikaans (which was known as an L2 by all speakers) into German (to test for lexicon and grammatical structures). This more formal part of the interview was usually interpreted as a competition or game, and frequently other family members or neighbors participated. Altogether 82 speakers were recorded in Swakopmund; a further 44 speakers were recorded in other towns in central Namibia (table 3, see also figure 1).

Table 3. Geographical location of participants.Footnote 15

Participants usually had two first names, a German name (which was always used in interactions with Whites) and an African name (which was used interchangeably with the German name in the township). Below I use pseudonyms reflecting the German names of participants. All interviews cited in the remainder of this paper come from the fieldwork in 2000.

6. Contexts of Acquisition

6.1. Learning German as Children

Although the work environment was by far the most important place for the acquisition of German some African Namibians acquired German as children, mostly as a result of being born of mixed African-German parentage. Their fathers and grandfathers were typically members of the colonial army who had settled in Namibia upon their discharge and married, or more commonly cohabited, with indigenous women. Many of the children and grandchildren born to such unions acquired some German in the home, and were subsequently sent to German mission schools for their education (see section 4.1).

Extract 11 comes from an interview with Irmgard (born in the 1920s, L1 = Otjiherero), the daughter of a German farmer and an Otjiherero-speaking mother. In 2000, when the interview was conducted, Irmgard was highly respected as a successful farmer in the mostly German-speaking community of Outjo. German has played an important role throughout her life, and has always been part of her identity.

(11) Ich ham so in schule, in Klein-Windhoek-schul, mein vater war ein Duitser, da hab ich von vater gelernt und dann in nach schule gegangen in Klein Windhoek, Katholische mission, da hab ich Duits gelernt […] mein vater, der hat mich grossgemacht, selber, zur schule geschickt, später hat der immer mir besorgt bis zur nächste schule, der war, mit neunzig Jahren ist der gestorben […] das Duits is doch im blut, man kann doch nicht vergessen

‘I have [learnt] it in school, in the school in Little Windhoek [a suburb of Windhoek], my father was a German, thus I learnt from the father and then went to school in Little-Windhoek, Catholic mission, there I learnt German […] my father, he brought me up, himself, sent me to school, later he always helped me for the next school, he was, he died when he was ninety […] the German is in the blood, one cannot forget it.’

Similarly, Hilda (also born in the 1920s, L1 = Afrikaans; see 4.1) grew up with German. Her grandfather was a German soldier who had married a Khoekhoe-speaking woman. Like Irmgard's father he spoke German with his children, and also grandchildren.

(12) Interviewer: Und was haben sie mit ihrem opa gesprochen?

Hilda: Duits, Duits, aber so bisschen auch Afrikaans dazwischen, ehm, so bisschen hat der angelern, dies Afrikaans war bisschen schwach, aber der hat Duits gesprechen, un die sohns ham, die kinder ham alle Duits gesprechen mit ihre vater, mein vater auch un so, wir ham bisschen schwach, wir ham bisschen schwach, aber wir ham, Duits, Afrikaans, so ham wir immer bisschen gemixt ne, das war eigentlich schlecht, man hat nie saubere Afrikaans kon sprechen, un auch nich saubere Duits, die ganze land is mal so, ehm, is immer so bisschen Duits.

Interviewer: ‘And what did you speak with your grandfather?’

Hilda: ‘German, German, but a little Afrikaans in between, ehm, he learnt a little bit. The Afrikaans was a little weak, but he spoke German, und the sons, the children all spoke German with their father, my father too, we [the grandchildren] are a little weak [in German], we are a little weak, but we speak it, German, Afrikaans, we always mixed a little, ne, that was actually bad, one could never speak pure Afrikaans, and also not pure German, the whole country is just like this, ehm, there is always a little German.’

In some cases within-family language transmission continued into the third generation. Flora, Hilda's daughter (born in the 1940s, L1 = Afrikaans), remembers speaking German to her grandfather (that is, Hilda's father) as a child. However, she (the first-born) was the only one among her siblings to do so.

(13) Ja, mein opa, oh mein opa war gut für mich immer, kaffee ham wir immer gemacht, lekker kaffee. Sag der: ‘Komm her!’ ‘Ja, opa, ich komme!’ [Laughter]

‘Yes, my grandpa, oh my grandpa was always good to me, we always made coffee, nice coffee. He says: “Come here!” “Yes, grandpa, I'll come!”.’

It is important to remember that for those with German ancestry social interaction with members of the matrilectal German community was legally restricted under apartheid. Like Black Namibians, they remained at the periphery of society; politically disenfranchised, they lived in designated Coloured townships and were only allowed to enter White areas for purposes of work. Yet, in all these families, the Maletzkis, the Brockerhoffs, the Dentlingers, the Hagedorns—to name but a few common surnames—the German history is remembered (and often cherished) across generations.

The home was not only a site of language acquisition for those who had German ancestry. Often parents or siblings were found to engage in informal teaching practices at home (inter-generational/intra-family transmission). This was motivated by their experience that knowledge of German can be an important resource on the tight Namibian job market as the more desirable, that is, less strenuous and better paid jobs, were usually available in German-owned businesses and shops. And German employers were known to insist on their staff speaking German to them (and serving German clients using German). Luzia (born in the 1940s, L1 = Otjiherero) described her first encounter with German as follows:

(14) Interviewer: Wo hast du Deutsch gelernt?

Luzia: Nur bei meine mutter, die war schon in die zeit von die Duitse, die hat auch bei die Duitse mense gearbeit, ihre mutter hat bei Duitse mense gearbeit, da hat die immer so gesprechen, dann hat die gesag, bring mir was, eine teller, bring mir, dann hab ich gesag, was is teller, dann weiss ich nie, dann hat die gesag, das is teller, die hat mir immer so, die hat uns immer so gelern, so bissen, bissen gelern.

Interviewer: ‘Where did you learn German?’

Luzia: ‘Only from my mother, she lived in the time of the Germans, she also worked for German people, her mother had worked for German people, then she always spoke this way, then she said, bring me something, a plate, bring me, then I said, what is a plate, then I don't know, then she said, this is a plate, she has always, this way, she has always taught us, just a little bit, taught us a little.’

And finally there are those who grew up on farms and came into contact with German at an early age when helping their parents with their daily duties and playing with the farmers’ children. Veronika (born in the 1930s, L1 = Khoekhoe) describes her childhood on a farm owned by a German-speaking family:

(15) Ich hab nur bei Duitse leute gross geword, in kiche, wir ham immer in das haus mit die kleine kinder auch gespielt un wir ham immer Duits gereden, weisst du, ich bin so gross geworden […] wir ham immer so mitgespielt, so rumgehn in busch, da was auch eine damm gewesen, da bei die farm, un da hab ich auch immer geswimm mit die kinder, das war gut gewesen.

‘I just grew up with German people, in the kitchen, we always played with the small children, in the house, and we always spoke German, you know, I grew up that way […] we also played with one another, walked around in the bush, there was also a dam, there at the farm, and there I swam with the children, that was good.’

6.2. Learning German as Adults

For most speakers, however, extensive L2 acquisition took place after they had entered the workforce. This usually happened around ages 12 to 16. As recalled by Heinrich (born in the 1930s, L1 = Otjiherero):

(16) Von die sule aus ham wir immer so helfe arbeit bei die Duitse leute gesucht und da ham wir Duits gelern, wir ham in store gearbeitet un gartenarbeit, im garten gearbeitet, und haushelfe, und alles ham wir gemacht.

‘From school we have always looked for help-work with German people, and that's where we learnt German, we worked in the store and garden work, worked in the garden, and house-help, we did everything.’

Martha (born in the 1930s, L1 = Oshiwambo) describes her first day at work, as well as the subsequent learning process, as follows:

(17) Ja, ich hab in Swakopmund gelern, in die haus, wann diese alte Duitse, die konn nich Afrikaans sprechen, nur Duitse, und dann sag die ‘Martha, hol mal, eh, hol mal teller’, ich bring ein koffie, ‘nein das is nicht’, ich muss, dann lern ich, oh, das is ein teller, das is ein tasse, das is ein, so hab ich gelern.

‘Yes I have learnt [German] in Swakopmund, in the house, when this old German, this one couldn't speak Afrikaans, only German, and then this one says: “Martha, bring, eh, bring a plate,” I bring a cup of coffee, “no, that isn't.” I have to, then I learn, oh, this is a plate, this is a cup, this is a, that way I learnt.’

These acquisition narratives are similar across speakers and seem culturally focused—sometimes they are about a plate, sometimes a cup, sometimes they are about the difference between flowers and carrots, which one was asked to fetch from the garden. It is this particular domestic context of acquisition that has given rise to the emic term Kiche Duits. Nicodemus (born in the 1920s, L1 = Khoekhoe) explains the origin of the language name as follows:

(18) Bei kiche nich, da musst Du lern, gib den gabel, gib den, diese becher, das is bei die kiche arbeiten, kiche auf Duits, diese art von lernen, das is die kiche, Kiche Duits, ehm, so is das, die lern-lern Duits, das is die, nich so viel zeug nie, aber nur da wo hast du die, en was kos die [laughter] un wo is deine mutter, so, das is die Kiche Duits und doch auch die grosse Duits, ja, was, auch die grosse Duits, was uns nich versteht.

‘In the kitchen, there you must learn, give the fork, give the, this mug, that is working in the kitchen, kitchen in German, this way of learning, that is the kitchen, kitchen German, ehm, it's like that, they learn-learn German, that is the, not so many things, but only where do you have, and how much does this cost [laughter], and where is your mother, so, that is Kitchen German, but also the big German, ja, what, also the big German, which we don't understand.’

The contrast between ‘big German’ and Kiche Duits, which Nicodemus describes in this extract, reflects a clearly perceived boundary between native and non-native forms of German in Namibia; a boundary which is also reflected in a number of common qualifiers which speakers use to describe their knowledge of German: nur ein bisschen (‘just a little bit’), nicht ganz (‘not fully’), so biekie-biekie (‘just little-little), so halb (‘just half’), halb-Duits (‘Half-German’) or ich probier maar (‘I am but trying’).

7. Within-Group Use: Crossing and Performance

Participants used German mostly at work with their German employer(s). However, Kiche Duits was more than a lingua franca for out-group communication. Isolated phrases such as wie geht's? (‘how are you?’), gut geschlafen? (‘did you sleep well?), mahlzeit (‘enjoy your meal’, ‘good day’), was machs-du? (‘what are you doing?’), angenehme ruhe (‘rest well’), verzeihung (‘sorry’) or tschüss (‘bye’) are regularly heard in the urban townships. These expressions are used not only by speakers of Kiche Duits but across township residents, irrespective of their proficiency in German. Just like English and Afrikaans, German thus occupies a place within linguistic repertoires, and expresses pragmatic and symbolic meanings within the substrate community.

Apart from pragmatic rituals such as greetings and apologies, there exist in-group contexts where Kiche Duits is used more extensively. Interview extracts 19–23 illustrate these uses which show an appropriation of the former colonial language within local community contexts such as competition games, conversational banter, swearing, the keeping of secrets, and codeswitching (see Pennycook, Reference Pennycook2001, for a useful discussion of the notion of “appropriation” in sociolinguistics; also Rogers Reference Rogers2006 and Park & Wee Reference Park and Lionel2008).

(19) Competition Games

a. Erwin (born in the 1940s, L1 = Khoekhoe; E = Erwin, I = Interviewer; switches into English in italics)

E: Da is stief leute, wir sprech Duits

I: Miteinander?

E: Ja, da is viele leute in Kattatura, aber die hat auch nie in sule gehabt, ja, wenn wir bisschen sprechen lass die andere nich hören was wir sprechen, dann sprech wir Duits, [laughter] like a competition, wo wir domino spielen, da sprech wir always Duits, ja sag mal ‘ich kann besser Duits sprechen’ oder ‘ich kann’, so was, nur männer.

E: ‘There are many people [in the township], we speak German.’

I: ‘With one another?’

E: ‘Yes, there are many people in Kattatura, but they didn't go to school, yes, when we speak a little so that the others don't hear what we speak, then we speak German, [laughter] like a competition, where we play domino, there we always speak German, ja, say “I can speak German better” or “I can,” like this, only men.’

b. Wilhelm (born in the 1930s, L1 = Khoekhoe; W = Wilhelm, I = Interviewer)

I: Wann sprechen Sie Duits mit anderen leuten?

W: Ja, wenn ich bisschen so besaufen hab, dann kann ich es auch, ‘mann, ich spreche Duits, und du nich’.

I: Und was sagen die dann?

W: Da sagt der ‘was kanns du mir erzählen in Duits?’, da sag ich ‘ach du weiss doch, ich hab lernen Duits, mann, ich weiss Duits, mann!’ ‘Du kanns doch nich Duits sprechen, wo hast du Duits gelern?’ ‘Ich hab bei E. gearbeiten, hier hab ich gearbeiten, hab ich die Duits gelern. Wo hast du die Duits gelern?’ ‘Ich hab bei B. Duits gelern, auch bei S. Duits gelern, da hab ich mit die Duitse leute gro-geworden’, un so, das is noch die sprache von die saubere, swarze leute—weiss du, so lerns-du noch wenn du noch nich so'n bisschen weiss, die ander weiss so'n bisschen mehr, so lernst du noch bei deine freund etwas.

I: ‘When do you speak German with other people?’

W: ‘Yes, when I am a little drunk, then I can: “Man, I speak German and you don't.”’

I: ‘And what do they say?’

W: ‘Then he says “what can you tell me in German?” Then I say “ach, you know, I have learnt German, man, I know German, man!” “You can't speak German, where did you learn German?” “I have worked for E., I worked here [in Swakopmund], I have learnt German. Where did you learn German?” “I learnt German at B., also learnt German at S., there I grew up with German people,” and so, that is still the pure language, black people, you know, and this way you learn also if you don't yet know a little, the other knows a little more, this way you learn something from your friend.

(20) Conversational Banter (quatsch-quatsch)

a. Hilda (Swakopmund, born in the 1920s, L1 = Afrikaans; H = Hilda, I = interviewer)

I: Was haben sie mit ihrem mann gesprochen?

H: Nein, wir ham nur Afrikaans zu hause, nich Duits, wir ham, ja, manchmal ham wir so für spass, ham wir so bißchen unterhalten, so bißchen mit Duitse, aber nich mit die kinder, nee.

I: ‘What [language] did you speak with your husband?’

H: ‘No, we only spoke Afrikaans at home, not German, we have, yes, sometimes we made a little conversation just for fun, a little with German, but not with the children, no.’

b. Thomas and Petrus (Omaruru, born in the 1930s and 1920s respectively, L1 = Khoekhoe,; P = Petrus, I = Interviewer)

I: Und jetzt? Sprechen sie beide zusammen manchmal Duits?

P: Bloß selten und bloß bisschen quatsch-quatsch [laughter], ohne vrouwens und was [laughter].

I: ‘And now? Do you sometimes speak German together?’

P: ‘Rarely and only a little nonsense, [laughter] without women and what [laughter].’

(21) Swearing/Scolding

Thusnelda and Lina (Windhoek, both born in the 1920s, L1 = Khoekhoe; T = Thusnelda, L = Lina)

T: Mein Oupa, die hat, uhh, die hat gesprech soos Duitse leute, die hat ganz so gut gesprech, wenn sie kwaad was, dann sprech sie die Duits [laughter].

L: Meine vater auch, die auch, ‘ich werd dir helfen, gleich, ich werd dir helfen, weißt du das?!’ Das is meine vater! Wenn wir kinders nich gut gemach und die muss immer sage ‘ich werd dir helfen, weißt du, komm mal net!’ [laughter].

T: ‘My grandfather he has, uhh, he spoke like German people, he spoke very well, when he was angry, then he spoke German [laughter].’

L: ‘My father too, he too, “I will help you, now, I will help you, do you know that!?” That's my father! When we children didn't do right and he must always say “I will help you, you know, just come now!” [laughter].’

(22) Keeping Secrets

Pauline and Martha (Walvis Baai, both born in the 1930s, L1 = Oshiwambo; P = Pauline, M = Martha, I = Interviewer)

I: Und sie beide, sprechen sie manchmal zusammen Duits?[Both laugh]

P: Wir hat immer bei die Duitse leute gearbeit.

I: Ja. Aber zusammen sprechen sie nich Duits? Immer Ovambo?

P: Nein, nein, nur wir

M: wenn, wenn

P: wenn wir zu viele vrouwen

M: viele leute, ne

P: und wir will was sagen

M: und ich will nich was sagen

P: die andere muß hören

M: ja

P: dann sprech wir Duits [laughter].

I: ‘And you two, do you sometimes speak German with one another? [Both laugh]’

P: ‘We've always worked for German people.’

I: ‘Yes. But together you don't speak German? Always Ovambo?’

P: ‘No, no, only we’

M: ‘if, if’

P: ‘if we are too many women’

M: ‘many people, ne’

P: ‘and we want to say something’

M: ‘and I don't want to say something’

P: ‘the others must hear’

M: ‘yes’

P: ‘then we speak German [laughter]).’

(23) Codeswitching

Flora and her nephew Alvwin (Swakopmund, Flora born in the 1940s, Alvwin in the 1980s, L1 = Afrikaans; F = Flora, L = Alvwin; switches into German underlined, switches into English in small caps)

F: Hy is baie stout. Weet jy wat het hierdie kind gemaak? Daar was hy nog kleine, daar was hy nog kleine. Die Eichholz het tog die slagterij gehad, nou hy het so ‘n buckel, ein, ein, richtig eine grosse buckel, ne, da kann der die kop nich oplig, ne, dann sagt der zu Alvwin ‘Alvwin, kom daar ‘n car aan?’ Toe kom ‘n car, dann sê Alvwin ‘nein!’ [laughter]

A: Hy het so gekyk het, ne: ‘Alvwin is das gut?’ Ek sê ‘ja’ [laughter]

F: Sien jy hoe stout is Alvwin

A: I was naughty the time [laughter]

F: Alvwin was stout. Ek wil nog koffie hê, is lekker, lekker meine kind

F: ‘He was very naughty. Do you know what this child did? I was still small then, he was still small then. The Eichholz who owned the butchery, now he has such a hump, a, a real big hump, ne, then he cannot lift the head, ne, then he says to Alvwin “Alvwin, is there a car coming?” Then there is a car coming, then Alvwin says “no!” [laughter]’

A: ‘He looked like this, ne: ‘Alvwin, is this good?’ I say “yes” [laughter].’

F: ‘See how naughty Alvwin is.’

A: ‘I was naughty the time [laughter].’

F: ‘Alvwin was naughty. I want more coffee, is nice, nice my child.’

Appropriation as a category of sociolinguistic analysis is closely linked to Rampton's (Reference Rampton1995) notion of language crossing, and Bakhtin's (Reference Bakthin1981 [1935]) work on ventriloquation. Appropriation, crossing, and ventriloquation describe acts of articulating socio-symbolic meanings through other people's voices, usually involving a movement across sharply drawn social and/or ethnic boundaries. Schmidt-Lauber (Reference Schmidt-Lauber1998) has documented the discursive construction of an exclusive German ethnicity in Namibia: African Namibians, irrespective of their language skills or ancestry, always remained outside of the boundaries of the German Sprachgemeinschaft (speech community; see also Owens Reference Owens2008). In examples 19–23 speakers challenge this dominant discourse about ownership (of language) and belonging (to a speech community), and express alternative cultural politics through practices of crossing (see also Rogers Reference Rogers2006 on appropriation and cultural resistance). Rampton (Reference Rampton1995:280) defines crossing as follows:

[C]ode alternation by people who are not accepted members of the group associated with the second language they employ. It is concerned with switching into languages that are not generally thought to belong to you.

Crossing is a special type of verbal performance, a marked mode of speaking in which individuals purposefully display their multilingual “verbal competencies” (Bauman Reference Bauman1977; see also Pennycook's Reference Pennycook2001 discussion of postcolonial performativity). The performative aspect is clearly visible in the speech genres of verbal competition games (19), and conversational banter (20). In both genres it is the speaker's language skills (performance competence) that form the focus of the interaction, not their actual content. Such verbal performances often show qualities of cultural ritual, and reflect “more or less invariant sequences […] not entirely encoded by the performers” (Rappaport Reference Rappaport1999:24, original was emphasized; see also Rampton Reference Rogers2006 on the link between crossing, performance and ritual). Verbal competition games, as visible in 19, contain well-defined sequences of:

(a) asserting one's language skills with reference to their provenance,

(b) challenging the other participants’ skills, and

(c) response sequences which follow the same formulae as (a) and (b).

Verbal competition games are particularly prominent among the Namadama, who would construct such games also around their skills in Otjiherero or Oshiwambo.

Ritual and performative qualities are also visible in the use of German for swearing (21). In this case the speech act of swearing is symbolically associated with a particular out-group language and a limited number of set phrases. This practice is widespread in Namibia and younger Namibians (who themselves did not know German) repeatedly mentioned their grandparents swearing at them in German. That German employers had a tendency to abuse employees verbally was a reoccurring theme in the interviews (as were memories of the Kommandosprache ‘commando language’ of the German colonial army, kept alive through stories told by other older relatives; see also section 9, examples 59–61). In-group swearing using German is best interpreted as an instance of “acting German,” that is, acting and speaking like the “master” (Adendorff, Reference Adendorff, and Mesthrie2002, reports similar in-group uses of Fanakalo, a South African pidgin).

Example 22 shows that knowledge of German is not only a valuable skill for finding employment in Namibia, but also a resource that allows speakers to keep conversations private (see appendix, flash 1). Example 23 illustrates the use of German as a stylistic device in conversation and narratives, showing both conversational and quotative codeswitching. Conversational codeswitching occurs mainly among those who—like Flora—grew up with German in the family (due to their mixed African-German heritage). Quotative codeswitching is common across speakers, and occured most typically in “employer-stories,” that is, stories about the people one had worked for, their idiosyncracies, and characteristics. These stories often had strongly subversive qualities, making fun of those in power.

During my fieldwork African Namibians repeatedly described themselves as swarze Duitse (‘Black Germans’) or Duitse jungen (‘German boys’), a self-description that reflects the multiplicity of identity brought about by colonial language and culture contacts. Their motivation for claiming “Germanness” was either their mixed African-European ancestry, or their life experiences of having worked for Germans for many years, and having thus absorbed, and made their own, aspects of language and culture. The quote at the beginning of this paper articulates this stance succinctly. It comes from an interview with Petrina, an 80 year-old Khoekhoe-speaking woman. Her words, spoken emphatically at the end of our first interview, provocatively question and “cross” the colonial and apartheid boundaries of “race” and language: Ich bin Duitse vrouw. Alte Duitse vrouw sein. Viele Duitse leute gearbeiten (‘I am a German woman. An old German woman. I worked for many German people’).

8. Non-Linguistic Crossing: Truppenspieler and “Traditional” Dress

Crossing is not only a linguistic concept, but can be applied to other aspects of social behavior. In Namibia, practices of crossing underpin the construction and expression not only of personal, but also of collective identities that have absorbed and appropriated aspects of the colonial “other.” In this section I discuss two cultural practices that have become strong ethnic signifiers, especially among the Ovaherero: the Truppenspieler movement and “traditional” female dress. These complex visualizations of cultural crossing allow us to locate the linguistic practices discussed above in the wider cultural matrix of colonial and post-colonial identities.

Truppenspieler

In 1916, one year after the South African military invasion, the new administration received reports about young African men wearing military uniforms and marching to and fro. These practices continued over the years and in 1928 the following eyewitness report was filed by a Sergeant Johannes in Windhoek:

At exactly 12 m.n. on 21.1.28 I was aroused by a Police whistle. I immediately got up and proceeded in the direction of the Damara Location from whence the whistle came. On nearing the Location, I saw a few hundred men lined up and engaged in going through some sort of military drill. At this sight I became very suspicious and decided to watch the performance for a while.

The whole Damara location was in darkness at the time and a big crowd of women and children watched the performance. I was hiding behind a W.C. about 15 yards away from the parade, but I could clearly hear the commands of the instructor. He gave his instructions in the German language, followed by sharp signals from his whistle (Windhoek National Archives A 50/59, 22.1.1928; my emphasis).

These marching groups of Namadama and Ovaherero were called otruppa/oturupa (‘troop’, Otjiherero borrowing from German), or Truppenspieler, lit. ‘troop players’; that is, those who “play” being soldiers by imitating military practices (dress, marching, drills, commandos).

Both Otjiherero- and Khoekhoe-speaking groups had a tradition of militarization. From the 1860s onward they had been organized into armed, uniformed, and mounted military units. Upon encountering the German Schutztruppe from the 1880s onward, German military practices and organization became an important point of reference. Already in the 1890s, Jacob Irle, a missionary in Okahandja, described with concern young Ovaherero men, wearing red headbands (to express their allegiance to Chief Samuel Maharero) and “playing” (that is, imitating) German soldiers:

It was as if these red bands had introduced a spirit of rebellion among the youth. People drilled, swore, drank excessively and aped the German soldiers (cited in Werner Reference Werner1990).

After the Herero-German War, many of those captured were employed as servants, and later soldiers, in the Schutztruppe. There they were, to some extent, “socialized in the confines of the [German] military” (Gewald Reference Gewald1999:265). The structures and traditions of the Schutztruppe became a loose model for the Truppenspieler movement in the aftermath of the war. The sometimes playful military practices of the Truppenspieler should not distract from the sociopolitical aspects of the movement. It functioned as an ethnically based welfare and support organization that brought people from dispersed settlements together, following the destruction of traditional indigenous networks (Werner Reference Werner1990, Gewald Reference Gewald1999: 263ff).

The German influence on the movement is unmistakable in the hierarchy of ranks and titles: The Kaiser (‘emperor’) of the regiment was supported by officers and soldiers, all of whom carried German titles: Oberst (‘colonel’), Leutnant (‘lieutenant’), Wachtmeister (‘constable’), Unteroffizier (‘corporal’), and Gefreiter (‘private’). When the South African Military Magistrate seized some documents belonging to the Kaiser of the Okahandja troop (Eduard Maharero), they found an array of assumed, almost theatrical “German” personas among his chief officers: the “native” Frederick, who worked for Dr Fock, was referred to as Governeur von Deimling, Jimmy and Mattheus who worked at the Gruners and Mr Kessler respectively were known as Oberstleutnant Leutwein and von Estorff, and finally there was Fritz, who worked for the Reverend during the day, and was called Adjudant Schmetterling von Preusen (‘Butterfly of Prussia’) at the nightly drills (Windhoek National Archives, A50/59, 19 May 1917). Letters issued by the movement carried the abbreviation M.P.S.M., which stood for Mukuru Puneti Samuel Maharero (‘God with us and Samuel Mahararo’), a direct translation of the royal Prussian motto Gott mit uns (‘God with us’).

First evidence of the Truppenspieler movement dates back to 1905; however, it was the funeral of Chief Samuel Maharero (c. 1854–1923), who referred to himself in German as König von Hereroland (‘King of Hereroland’), which contributed to the formalization and elevation of these practices:

In Okhahandja, on a cold winter's day in 1923, an honour guard of Herero soldiers dressed in German uniforms, wearing German military ranks, and marching to German commands, carried a coffin to the grave. A military brass band, which played a German funeral march, and 170 mounted Herero soldiers, riding four abreast, preceded the coffin […]. In effect the funeral, in its outward appearances, was identical to those which had been given to high-ranking German officials […] full of pomp and ceremony, marching brass bands, mounted soldiers, and massed ranks of soldiers […]. For the Herero the funeral of Samuel Maharero was the largest socio-political event since the Herero-German war […]. The funeral demonstrated to the Herero and the outside world that they were once again a self-aware, self-regulating political entity, with their own unique identity (Gewald Reference Gewald1999:274, 279, 282).

A unique identity, one might add, which self-consciously appropriated colonial practices and symbols, reviving their own military traditions through the mirror of their colonial experience (see Ranger Reference Ranger, , Hobsbawm and Terence1983 and Spear Reference Deumert2003 for similar observations regarding British colonies in Africa). It was a subversive move, a continuation of the fight against domination: wearing the cloth of the enemy was also believed to weaken his spirit (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson, and Hendrickson1996:227; note that under South African administration uniforms came to include symbols of the new regime).

The Truppenspieler movement is still active today among the Ovaherero and the various troops parade each year on Herero Day in Okahandja. Several of the male speakers included in this study proudly showed me their German-style uniforms, their military passes (complete with German-sounding pseudonyms), and reported early morning marching drills with German commands. The practice has disappeared among Khoekhoe-speaking groups; however, older speakers still remembered these practices to have been alive until the 1960s.

“Traditional” dress

Another example of non-linguistic crossing and cultural appropriation is the form of the so-called “traditional” female dress of Namadama and Ovaherero women (Hendrickson Reference Hendrickson1994).

The garments are visually striking: reminiscent of Victorianera fashions women wear a heavy dress with long voluminous skirts (supported by several petticoats), a high and tightly bound waist, and billowing long sleeves (figure 3). Added to this is a shawl and a distinctive headdress which is constructed out of two scarves. This style of dress differs markedly from pre-colonial attire (figure 4), as well as the simple, white colonial dresses of domestic servants (figure 2): the colors are bold, the materials patterned, not infrequently showing printed portraits of popular African leaders (Durham Reference Durham and Joanne1995:192; see also Ross Reference Garrett2006; this style of dress was reported in the Deutsche Kolonialzeitung already in 1908). When I was conducting fieldwork in 2000 only Namadama women in their 70s and 80s, and Ovaherero women around 50 and older would wear the dress daily. Younger Ovaherero women still wore the dress to important cultural events.

Figure 3. “Traditional” dress, c. 1930s (l. Koloniales Bildarchiv, no. 028-2305-11; detail from group picture; r. Koloniales Bildarchiv, no. 028-2305-03).

Figure 4. Herero woman, n.d. (Koloniales Bildarchiv no. 071-2999-007).

Today, the long dress is considered “traditional” and a strong marker of ethnic, especially Ovaherero, identity. Yet, its colonial origins are overtly and proudly acknowledged, reflecting the dynamic, and often hybrid, nature of post-colonial tradition in Africa. As noted by Durham (Reference Durham1999: 399–400):

Herero women's reflections on their dress are a counter-example to a widely held notion that tradition (especially outside the West) is necessarily represented as timeless, ineffably local, and autogenetic […]. Herero occasionally pass time by discussing the transnational aspects of their dress, even when not pestered by anthropologists […]. In all of these reflections, Herero actively chose and borrowed from other nationalities […]. Although historical documents talk about a Herero capitulation to European dress in the heavily oppressive conditions following the German-Herero War of 1904, the histories related by Herero women […] tell of dynamic exchange and positive action, with choice and independent agency as central features (see also Durham Reference Durham and Joanne1995).