Introduction

Despite robust evidence associating individuals with active psychosis with a degree of risk for violence, it remains challenging to predict and prevent violent incidents in this population.Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 Studies aiming to characterize violence in patients with psychosis have highlighted the difficulty of predicting and preventing violence because it is a rare and complex event.Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 , Reference Nestor 2 For example, patients with psychosis may behave violently as a direct result of their psychotic symptoms, due to other factors that increase risk in the context of psychosis or for other reasons unrelated to their illness.Reference Nestor 2 The relationship between psychosis and violence is especially relevant in forensic psychiatry due to the relatively high prevalence of violent incidents, psychotic disorders, and the emphasis on mitigation of the risk for violence in forensic population—prevention of recidivism.Reference Campbell, French and Gendreau 3 Describing common pathways that are related to violent behavior in this population may uncover opportunities for more nuanced risk assessment and targeted intervention.

The characterization of violence in patients with psychosis in existing literature has often related violence to certain panels of few clinical factors, including active psychotic symptoms, low treatment adherence, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior.Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 , Reference Sedgwick, Young, Baumeister, Greer, Das and Kumari 4 –Reference Elbogen and Johnson 6 This construct of violence based on these panels of clinical factors often implies that violence can result from at least two pathways: acute psychopathology or premorbid conditions.Reference Sedgwick, Young, Baumeister, Greer, Das and Kumari 4 –Reference Elbogen and Johnson 6 However, such construct is limited because these factors are neither necessary nor sufficient to cause violence. For example, some studies aiming to describe an explanatory model for propensity for violence have highlighted various biological, psychological, and social differences or factors.Reference Witt, Van Dorn and Fazel 5 In this regard, brain imaging studies have reported functional deficits in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdalae of violent patients, possibly leading to impairments in executive functioning and emotion regulation, compared to nonviolent patients.Reference Fjellvang, Grøning and Haukvik 7 In psychology literature, the relationship between psychosis and violence has been proposed to be moderated by cognitive impairment, psychopathy, and negative affective states.Reference Reinharth, Reynolds, Dill and Serper 8 –Reference Adams and Yanos 10 Similarly, studies focusing on social and environmental factors have related violence to low social support, childhood trauma, and victimization as adults, among others.Reference Ten Have, De Graaf, Van Weeghel and Van Dorsselaer 11 , Reference Bosqui, Shannon, Tiernan, Beattie, Ferguson and Mulholland 12

While existing studies on violence and psychosis provide valuable data for understanding the correlates of violent behavior in psychosis, their findings have not led to blockbuster improvements in clinical practice or patients’ outcomes. Risk assessment currently relies on a combination of clinical judgment, which has been shown to have low validity on its own, and structured assessment measures, which have been criticized for lacking validation and nuance in forensic psychiatric patients with psychosis (FPPP).Reference Murray and Thomson 13 –Reference Singh, Serper, Reinharth and Fazel 15 Even the most robust risk assessment tools predict violence with only small to moderate effect sizes, suggesting that they may benefit from additional indicators of risk and integration of emerging evidence using innovative practices and recent advancements in technology.Reference Brown, O’Rourke and Schwannauer 16 , Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17

Most of the existing evidence on the relationship between violence and psychosis comes from studies conducted in the general psychiatric population.Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 , Reference Nestor 2 , Reference Sedgwick, Young, Baumeister, Greer, Das and Kumari 4 , Reference Witt, Van Dorn and Fazel 5 However, the forensic psychiatric population is unique, and findings in the general psychiatric population may not be representative of them. For instance, FPPP tend to have a higher prevalence of violent incidents and comorbid conditions, more severe clinical phenotypes, and a different treatment context compared to the general psychiatric patients, all of which can modify their risk of violence.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 Moreover, given that most patients in the forensic psychiatric system had previous contact with general psychiatric mental services, they may represent a particularly high-risk or special group of patients that could have been identified earlier in their trajectory with the proper tools and understanding of their risk profile. Identifying high-risk groups depends on forming an evidence-based biopsychosocial–clinical gestalt that goes a step further than individual characteristics. We conducted this review to characterize violent behavior among FPPP. Specifically, this study provided an overview of the characteristics of the violent incidents and behavior in FPPP and discussed the clinical implications of these findings in light of the need for optimal assessment and mitigation of violence risk in forensic settings.

Methods

The present study was completed following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt 19 Eligibility included all study designs (e.g., cross-sectional studies, retrospective chart reviews, prospective observational studies, and interventional trials) published till 2023. We excluded correspondences, editorials, case reports, case series, protocols, reviews, and articles in languages other than English. Eligible studies needed to have samples consisting of forensic psychiatric patients above the age of 18 with findings of “not criminally responsible” or “permanently unfit to stand trial” or equivalent findings in their jurisdiction. Some fraction of the study participants needed to have psychotic disorders or psychotic symptoms, with an independent description of this group. Eligible studies also needed to comment on violence as a primary outcome or focus of the study.

Search strategy

Search strategy was developed in consultation with the librarian at the McMaster University Health Sciences Library. We searched major databases, including CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline/PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science using a combination of keywords and database-specific subject headings for violence, psychosis, and forensic psychiatry. [See Supplementary Material S1 for search strings, and strategy used for the databases]

Study selection

Screening, quality assessment, and data extraction were conducted independently by AS, SB, WP, and supervised by ATO. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by at least two authors to select studies eligible for full-text review. Full-text articles were reviewed, and data extraction was completed independently by at least two authors according to the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between reviewers or in consultation with the senior author (ATO) to reach consensus.

Quality assessment

The Study Quality Assessment Tools of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were used to determine the quality of the included studies. 20 All authors rated each study on a range of 12–14 items based on the study design to determine their methodological strengths, limitations, and risk of bias. Scores from all three authors were collated, and disagreements were resolved by discussion between authors or in consultation with ATO. Studies were determined to be good, fair, or poor quality based on their average score relative to other included studies.

Data collection and presentation

Relevant data points were extracted independently by at least two authors from each included study. Data items were decided a priori and included study characteristics, participant characteristics, assessment of psychosis, assessment of violence, main findings, clinical recommendations, and study limitations. We organized the patients’ characteristics that emerged from the included studies into five domains: clinical, criminological, biological, psychological, and social domains. Patient subgroups with similar characteristics or profiles were described next. Given the heterogeneity of assessment and outcome measures, a meta-analysis could not be conducted.

Results

Study selection

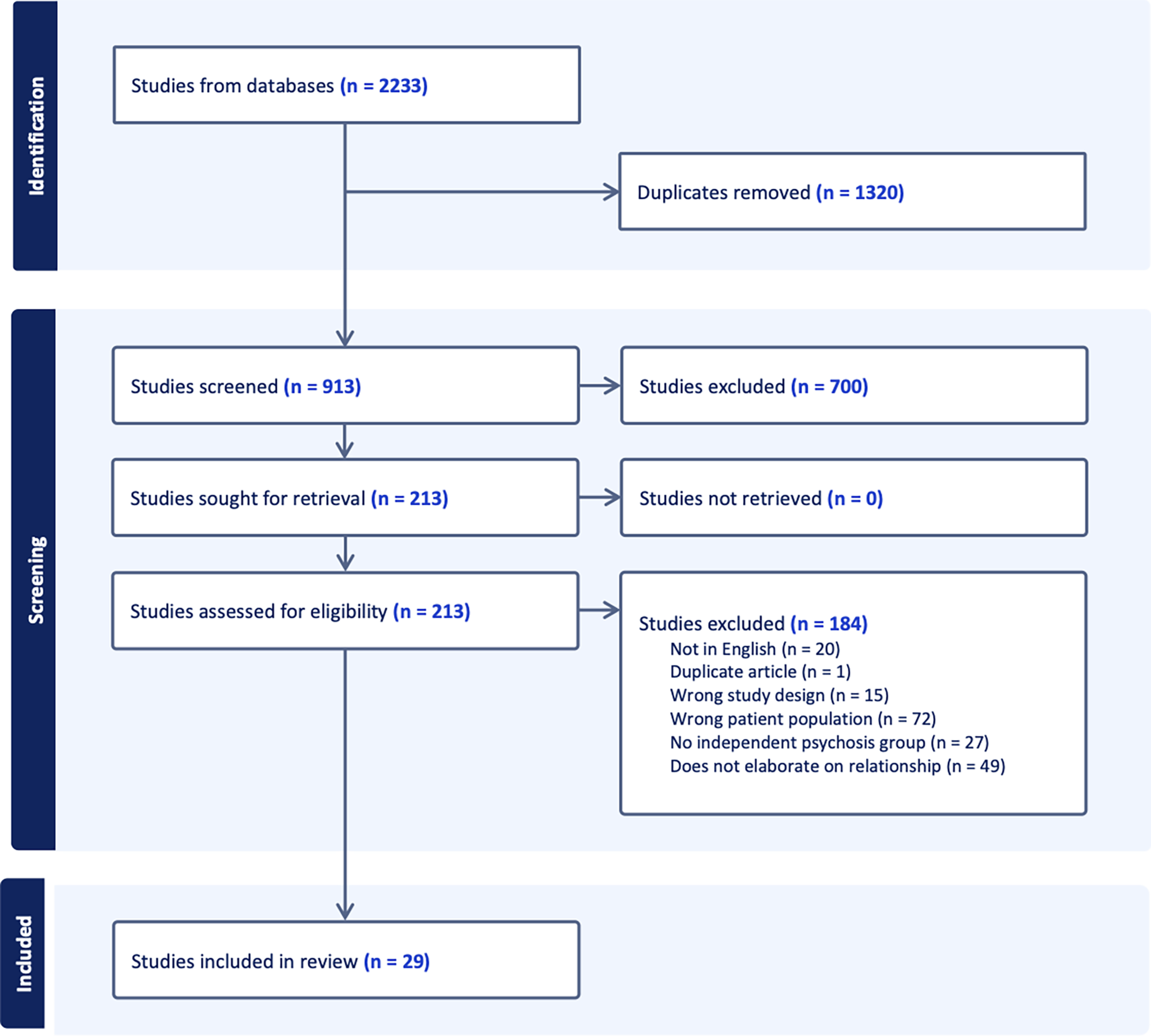

Of a total of 913 reports identified from all databases after duplicates were removed, 29 eligible articles were selected for inclusion in the final report.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 –Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 The screening and selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram.

Study characteristics

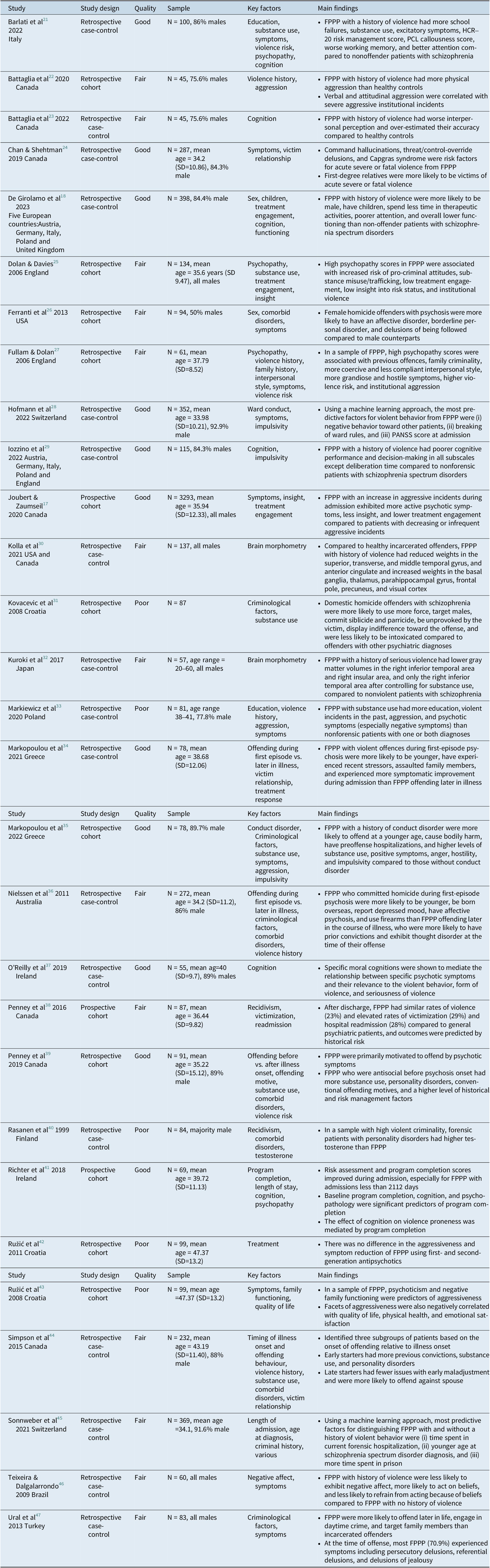

Table 1 presents the characteristics and main findings from the included studies (n = 29). The publication dates of the included reports spanned three decades, from 1999 to 2023, with 16 studies that were published in the last 5 years. Majority of the eligible studies were conducted in Canada (n = 7), Croatia (n = 3) and two each in England, Greece, Ireland, and Switzerland. Two studies included settings across several European countries (and one report each was from Australia, Brazil, England, Japan, Poland, Turkey, and the USA. Only three studies had prospective study designs,Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Richter, O’Reilly and O’Sullivan 41 and we assessed 11 studies as high quality, 13 studies as fair quality, and 5 studies as poor quality. [See Supplementary Material S2 for detailed results of the quality assessment].

Table 1. Summary of Studies Included in the Systematic Review

Abbreviation: FPPP, forensic psychiatric patients with psychosis.

In all the included studies, there were a total of 7,042 participants, consisting of inpatients in forensic settings, albeit six studies included participants from outpatient forensic settings.Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Six studies focused on severe violence (defined as homicide, attempted homicide, or serious injury to the victim)Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Richter, O’Reilly and O’Sullivan 41 –Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43 , Reference Teixeira and Dalgalarrondo 46 and two studies only included homicide offenders in their sample.Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 With the exception of the study by Ferranti and colleagues,Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 all studies predominantly included male participants, and six studies had male samples entirely.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Dolan and Davies 25 , Reference Kolla, Harenski, Harenski, Dupuis, Crawford and Kiehl 30 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Teixeira and Dalgalarrondo 46 , Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis across the samples.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 –Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 –Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 The dyad of cases and controls recruited across the included studies varied significantly: five compared FPPP with the general psychiatric populationReference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Teixeira and Dalgalarrondo 46; four compared FPPP with and without violent behaviorReference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45; and three compared FPPP to healthy individuals.Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Räsänen, Hakko and Visuri 40 Furthermore, two studies each compared FPPP with nonforensic offendersReference Kolla, Harenski, Harenski, Dupuis, Crawford and Kiehl 30 , Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47; and individuals with high and low trait psychopathy scores.Reference Dolan and Davies 25 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 Some studies (n = 2) compared FPPP who started offending prior to the onset of illness and those who started offending afterward,Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 and two reports compared FPPP who offended during the first-episode psychosis with those who offended later in the course of the illness.Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 One study compared FPPP with more and less severe violenceReference Chan and Shehtman 24; one compared FPPP to forensic patients with other diagnosesReference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31; one compared FPPP with and without a history of conduct disorderReference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35; one compared female and male FPPPReference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26; one compared FPPP with longer and shorter admissionsReference Richter, O’Reilly and O’Sullivan 41; and one compared FPPP treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics.Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43 Three studies lacked a control group.Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 42

Findings on violence from the included studies

The main findings on violence in FPPP in the included studies (n = 29) are presented in Table 1 and summarized below.

Clinical characteristics associated with violence in FPPP

Previous psychiatric history

A significant proportion of FPPP with violent behavior (89%) had received psychiatric treatment before the index offenseReference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 and FPPP were more likely to have received psychiatric treatment before the index offense in a study that compared offenders with individuals with nonschizophrenia psychiatric diagnoses (χ2 = 6.183, p = 0.013).Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 Active contact with mental health services shortly before the offense was reported in 71.4 and 78.1% by two reports, and 66.7%–88.1% were prescribed antipsychotic medication and 21.7%–85% adhered to treatment in the same reports.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 One report that used machine learning model found that olanzapine equivalents at discharge were a predictor of belonging to FPPP with violent rather than nonviolent offences.Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 On a different note, no difference in aggressiveness (t = -0.13, p = 0.895), side effects (t = -0.23, p = 0.819), and length of hospitalization (t = -0.87, p = 0.387) was found when first- and second-generation antipsychotic medications were compared in FPPP with violent behavior.Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43

Psychotic symptoms

Psychotic symptoms were associated with violent behavior,Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 and as much as 79.2–97% of FPPP experienced delusions at the time of the offense.Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Persecutory delusions were the most common.Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 , Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 In two reports, 79–87.9% of patients endorsed auditory hallucinations, of which 24.2–49.3% were command hallucinations.Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Two machine learning studies found that the severity of psychotic symptoms was among the most predictive variables of violent behavior in FPPP.Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 In some studies (n = 4), psychotic symptoms were confirmed as common prior to and at the time of the index offense and were present in the days to weeks prior to the offense.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 Comparing symptom severity between patients with and without a history of violent behavior produced mixed results, including De Girolamo and colleaguesReference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 reporting no significant difference (p=0.226) while Barlati and colleaguesReference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 reported more severe excitatory symptoms in the violent group (p < 0.001).

Personality disorders

The prevalence of personality disorders among FPPP with violent behavior varied between 3.37 and 28.4% across all the included studies.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 Compared to nonforensic samples, FPPP with violent behavior were more likely to have personality disorders (p < 0.005).Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) was the most common personality disorder across studies, with its prevalence ranging from 14.4 to 28%.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43 Further, FPPP were more likely to be diagnosed with ASPD than nonforensic patients (p = 0.002).Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 Similarly, FPPP with a history of conduct disorder were more likely to offend at a younger age (U = 522.500, p = 0.042), cause bodily harm, use substances (χ 2 = 3.661, p = 0.056), and engage in more violence directed toward others following the offense (χ 2 (1) = 6.255, p = 0.012), and exhibited more severe positive psychopathology (t(76) = 2.036, p = 0.045) even after treatment.Reference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35

Substance use

The prevalence of substance use disorder among FPPP with violent behavior ranged widely from 10 to 82.2%.Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 , Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 At the time of the offense, 20–47.2% of FPPP were reported to have recently used alcohol or other substances.Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 One study determined that 30.4% of the sample experienced symptoms that were caused or exacerbated by substance use before the offense.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39

Criminological characteristics associated with violence in FPPP

Criminal history

Two studies reported that the prevalence of previous criminal convictions among FPPP with violent behavior was 44% and 66.5%.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 One machine learning study identified that time spent in prison and number of criminal record entries were among the most predictive variables for distinguishing FPPP with and without violence offences.Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 On average, there was a 2-year interval between the onset of psychotic symptoms and violent offending and a 6.3-year interval between initial psychiatric evaluation and violent crime.Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 Another study found that FPPP had fewer violent convictions compared to nonforensic offenders (χ2 = 5.12, p = 0.02).Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47

Nature of index or present offense

Across samples, 50–67.9% of patients were reported to perpetrate severe or fatal violence.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37 One study reported that FPPP were more likely to use physical force than forensic patients with other diagnoses (13.6% and 7.0%, respectively).Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 Another study found that patients motivated by psychotic symptoms were more likely to commit severe offences (χ2 = 12.13, p < .05) and cause harm (χ2 = 9.54, p < .05) compared to patients with predominantly disorganization or mood symptoms.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Regarding weapons used in the offense, one study reported that FPPP with violent offences most frequently used knives (52%).Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 Another found that the most common method of assault was using hands (44.2%), followed by sharp or blunt instruments (34.6%), and this was not significantly different from nonforensic offenders (p > 0.05).Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 The prevalence of FPPP committing violent offences against family members or intimate partners varied from 25.5 to 76%.Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 One study reported that this was higher than the percentage of nonforensic offenders (10%).Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 One study found that offences against first-degree relatives were associated with severe violence (χ2 = 8.52. p = 0.004).Reference Chan and Shehtman 24

Biological characteristics associated with violence in FPPP

Approximately, 22% of FPPP with violent behavior had previous brain injuries with loss of consciousness.Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 Furthermore, a brain morphometry study found that FPPP with violent behavior had greater loading weights in the frontal pole, precuneus, visual cortex (F1,132 = 13.1, p < 0.001), basal ganglia (F1,132 = 9.7, p = 0.002), thalamus, parahippocampal gyrus ((F1,132 = 16.5, p < 0.001) and lower loading weights in the anterior cingulate (F1,132 = 11.4, p = 0.001), superior, transverse, and middle temporal gyrus compared to nonforensic offenders without psychosis.Reference Kolla, Harenski, Harenski, Dupuis, Crawford and Kiehl 30 Another study found that FPPP with violent behavior had lower gray matter volume (GMV) in the right inferior temporal area (p = 0.001) and the right insular area (p = 0.003) compared to nonoffender patients with schizophrenia.Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32

Psychological characteristics associated with violence in FPPP

Psychological motive related to the offense

In a report, 70.3% of FPPP were reported to be primarily motivated to commit their index offense by psychotic symptoms and acted consistently with its content and themes. In 15.4% of these cases, there was a secondary conventional motivation, most often reactive anger (59.1%) or antisocial attitudes (31.8%), contributing to their offense.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Two other studies reported that the violence perpetrated by FPPP was more often reactive (69% and 73.1%) than instrumental (31% and 26.9%).Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37

Personality structure

In two studies, FPPP with violent behavior scored higher on measures of overall aggression compared to nonforensic patients with schizophrenia (ω2 = 0.11, p = 0.004) and measures of physical aggression (t(43) = 2.10, p = 0.042) compared to healthy controls.Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 Similarly, FPPP with violent behavior were reported to have more difficulty with interpersonal perception (t = -3.14, p = 0.003) especially with respect to identifying kinship dynamics (t = -2.70, p = 0.010)Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 and have higher trait psychopathy than nonforensic patients with psychosis (p < 0.001) and PCL-R “callousness” predicted belonging to the forensic group (p = 0.031).Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 Psychopathy was also associated with other risk factors, including previous offences as an adult (χ2 = 5.08, p = <0.05), family criminality (χ2 = 4.71, p = <0.05), positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) hostility (Mann–Whitney U = 262.00, p < 0.01), PANSS grandiosity (Mann–Whitney U = 281.50, p < 0.05), total historical, clinical and risk management-20 (HCR-20) score (t(57) = 4.09, p < 0.001). In this sample, FPPP in the high psychopathy group displayed a more hostile interpersonal style in interactions with staff and patients and were more likely to engage in institutional aggression than those with low psychopathy scores (χ2 = 7.1, p < 0.01).Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 Similarly, another study reported that FPPP with high psychopathy scores were more likely to have procriminal attitudes (AUC 0.89 (SE 0.03) p = 0.000), low work ethic (AUC 0.78 (SE 0.05), p = 0.000), low insight into their violence (AUC 0.72 (SE 0.05) p = 0.003), substance use (AUC 0.77 (SE 0.04), p = 0.000), and institutional incidents (AUC 0.65 (SE 0.04), p = 0.002).Reference Dolan and Davies 25 Antisocial behavior during admission predicted institutional violence in one machine learning study.Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28

Cognitive ability

In their report, de Girolamo et al. found that FPPP with violent behavior had poorer performance in verbal memory (p = 0.015), verbal fluency (p = 0.021), and processing speed (p < 0.001) compared to nonforensic patients with psychosis.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 Similarly, others have reported poorer working memory (p = 0.037) and processing speed (p = 0.026) but better attention (p < 0.001) in FPPP with violent behavior compared to nonforensic patients with psychosis.Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 On measures of impulsivity, FPPP with violent behavior exhibited more risk-taking behavior (t = -2.09, p = 0.039) and less deliberation time (95% CI 277.1–1.625.4, p = 0.003) as compared to nonforensic patients.Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 Specific moral cognitions were shown to mediate the relationship between specific psychotic symptoms, relevance to violence, form of violence, and seriousness of violence.Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37 Again, an assessment of inpatient program completion showed that the effect of cognition on violence risk was mediated by changes in program completion.Reference Richter, O’Reilly and O’Sullivan 41

Social characteristics associated with violence in FPPP

Adverse childhood experiences

Approximately 15% of FPPP with violent behavior experienced childhood trauma (χ2 = 0.00, p = <0.549)Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 and history of childhood abuse was common in several FPPP samples.Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35 One machine learning study found that childhood poverty was a robust predictor of belonging to FPPP with violent rather than nonviolent offences.Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 In the same vein, FPPP with violent behavior were more often victims of violence (p = 0.186) or had witnessed violence (t = 4.36, p = 0.037) compared to nonforensic patients with psychosis (26.7% and 17.9%) (p = 0.186).Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29

Social support

With respect to support, 26.4% of FPPP with violent behavior were observed to have no fixed address when they committed their index offense.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Across studies, 54.5–90% of FPPP with violent behavior had never married,Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 42 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 although one study noted that FPPP with psychosis were more likely to have children (t = 4.77, p= 0.029) and even so in those with schizophrenia (p = 0.004)Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 compared to nonforensic patients with psychosis. Both negative family functioning and poor quality of life were predictors of aggressiveness (p < 0.05) in a report.Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 42 According to a machine learning model, social isolation in adulthood was identified as a strong predictor of belonging to FPPP with nonviolent rather than violent offences, with rates of 84.9% compared to 68.1%.Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45

Education and employment

Across studies, most FPPP with violent behavior were often less educated compared to the control group,Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 and one report found that FPPP with violent behavior had more school failures than nonforensic patients with psychosis (χ2 = 823.0; p = < 0.002).Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 Another study reported that education was protective against violence (p < 0.001), with each year of education leading to a 12% reduction in the probability of belonging to the violence group.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 Rates of unemployment among FPPP at the time of their violent offense were high, ranging between 40.9 and 80.6%.Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45

Characterization of violence in FPPP based on subgroups with clinical relevance

Male and female offenders

Ferranti et al. compared male and female FPPP with homicide offences.Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 The study reported that females were more likely to use knives (43% vs. 32%, p < 0.05), offend against victims under 18 years old (44% vs 0%, p < .001), target family members (64% vs. 25%, p < .001) have borderline personality disorder (60% vs. 9%; p < 0.05), and present with an affective component to their illness (51% vs. 21%, p < 0.01) be the victim of childhood sexual abuse (58% vs. 18%, p < 0.01) and intimate–partner violence (65% vs. 19%, p < 0.01).Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26

Violent offending relative to illness onset

Some of the studies on FPPP have dichotomized their sample into groups to understand offending before and after the onset of illness.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 The findings indicated that FPPP who were arrested for violent crimes prior to psychiatric symptom onset (“early starters”) had higher rates of trauma, poor social support, substance use disorder (χ2 = 4.11, p < .05), personality disorder (especially ASPD; χ2 = 5.83, p < .05), and treatment nonadherence compared to FPPP who started offending after illness onset (“late starters”).Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 Similarly, early starters reported higher rates of psychopathy (F (2, 164) = 13.24, p < 0.01) and previous criminal convictions (F (2, 219) = 8.84, p < 0.01)Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 and were more likely to have nonillness related motives for offending (χ2 = 4.14, p < 0.05), whereas late starters were often motivated to offend by psychotic symptoms.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 A third group of FPPP who offended after 10 years of illness or past the age of 37.5 years (“late-late starters”) was more likely to offend against their spouse (χ 2(2, N = 232) = 9.00, p = 0.01).Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 These differences were also reflected in their overall risk, with early starters carrying the highest level of risk and criminogenic need.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44

Violent offending relative to the illness course

The course of illness was also used to understand violent offending along the trajectory of a psychotic illness. In this respect, patients were disaggregated based on whether their index offense occurred during the first episode of psychosis (“FEP offenders”) or later in the course of illness (“later offenders”).Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 Compared to later offenders, FEP offenders were more likely to commit severe index offences (p = 0.010). Their actions were more likely to be motivated by delusions (p = 0.004) and persecutory ideation (p = 0.015) in the FEP group. Their index offences were also more often preceded by a stressful life event (χ2= 4.805, p = 0.028) and followed by a suicide attempt.Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 A study reported that FEP offenders were more often born overseas (χ2= 20.4, p = 0.001) in a non-English speaking country (χ2= 39.7, p = 0.001), report depressed mood at the time of the offense (χ2= 8.76, p = 0.003), and use a firearm to commit their offense (χ2= 5.94, p = 0.014).Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 By comparison, later offenders were more likely to have chronic psychopathology and worse overall outcomes (p = 0.032).Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 Both studies found that later offenders were more likely to have prior convictions than FEP offenders (p < 0.05).Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36

Violent offending during admission

One study identified three subgroups based on institutional violence over 18 months.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 Patients who had moderate aggression at baseline and became more aggressive over time were more likely to exhibit active psychotic symptoms, emotional and behavioral dysregulation, family problems, low treatment adherence, and low insight than patients who exhibited low aggression or became less aggressive.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17

Violent offending after discharge

Considering violent behavior among FPPP within 12 months after forensic discharge,Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 FPPP had high rates of victimization (29%) and hospital readmission (28%) but comparable rates of violence (23%) compared to patients discharged from general psychiatric services. They reported that historical risk factors (e.g., previous violence, young age at first violent incident, relationship history) were predictive of all three aforementioned outcomes with no additional contribution of dynamic risk factors.Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38

Discussion

This review presents findings from a qualitative synthesis of findings in 29 eligible studies that examined violence among FPPP covering several international contexts, albeit with a particular slant toward countries where forensic psychiatric practice is well developed. While the study findings buttressed the need for novel approaches to the assessment and management of violence, some of the observations in the included studies are generally consistent with previous reviews from the general psychiatric populations, underscoring the significance of clinical and other criminogenic factors in relation to violence in FPPP.Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 , Reference Witt, Van Dorn and Fazel 5 Ultimately, we hope the findings in this review will improve the current understanding and advance the assessment and management of violence in forensic psychiatric settings.

Findings from the included studies showed that FPPP who reported violence were more likely to have prior contact with psychiatric services, active psychotic symptoms, impulsivity, adverse childhood experiences, and poor social support.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 , Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 Notably, violence in FPPP was related to experiencing active psychotic symptoms prior to and during their offense, with persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations being the most common.Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 –Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 Also, comorbidities of both substance use disorders or personality disorders (most often ASPD) were related to violent behavior among FPPP, and both comorbidities were shown to exacerbate the risk of violence.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 –Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 43 –Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 , Reference Ural, Öncü, Belli and Soysal 47 Taking together, the above findings highlight the importance of assessments coupled with early and effective management of mental health and addiction problems to mitigate the risk of violence and avert future violent offending.Reference Pollard, Ferrara and Lin 48 , Reference Whiting, Glogowska, Fazel and Lennox 49 This is particularly important because the literature suggests that FPPP with violent offences had frequent contact with psychiatric services prior to their index offenseReference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39; however, assessment of violence as well as treatment adherence can be variable and challenging.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Whiting, Glogowska, Fazel and Lennox 49Numerous strategies to improve adherence (e.g., psychoeducation, insight counseling, motivational interviewing, use of depot medications and integrated community care etc.) have been described as beneficial to support mitigation of violent offences.Reference Pollard, Ferrara and Lin 48 –Reference Zygmunt, Olfson, Boyer and Mechanic 51 Notably, long-acting injectable (LAIs) antipsychotics have been linked with good adherence and overall outcomes due to their practical and pharmacokinetic advantages.Reference Whiting, Glogowska, Fazel and Lennox 49 Pertinent to this review, LAIs have been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of violence in patients with psychosis and prior violence.Reference Whiting, Glogowska, Fazel and Lennox 49 However, none of the included studies in this review commented on the impacts of LAIs compared to oral medications on violence in this population, pointing to the need for further investigation on this topic. On a related note, indicated assessments, treatment, and care should be provided to individuals with persistent, severe, or resistant symptoms using evidence-guided interventions to mitigate violence.Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 For example, clozapine has been shown to have beneficial effects for preventing violence, especially in patients with treatment-resistant psychotic illness or significant comorbidity, and has been linked with an antiaggression effect that is independent of its antipsychotic effect.Reference Frogley, Taylor, Dickens and Picchioni 50

It is important to highlight that violent offences among FPPP varied significantly in their severity, motive, and victim.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37 In acute psychosis, FPPP are generally more likely to cause severe violence and target family members than other violent offenders.Reference Chan and Shehtman 24 , Reference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Nielssen, Westmore, Large and Hayes 52 Consequently, experts have suggested the role of multiple criminogenic factors beyond psychosis and other associated clinical factors. In support of this formulation is the finding that FPPP with previous violent convictions were associated with aggressive incidents even after the resolution of their psychosis.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 In this regard, biological and cognitive findings have been proposed to explain additional risk for violence in FPPP. For instance, neuroimaging findings in FPPP with violent behavior included reduced temporal and frontal lobe volumes, particularly in the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex) and these are consistent with those elucidated in ASPD.Reference Kolla, Harenski, Harenski, Dupuis, Crawford and Kiehl 30 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Cho, Shin, An, Bang, Cho and Lee 53 , Reference Dean, Moran and Fahy 54 Furthermore, lower grey matter volume in the insular cortex was associated with premeditated violence compared with impulsive violence in FPPP.Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 While FPPP could be motivated to commit violent offences for illness-related or conventional reasons,Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 premeditated offences and conventional motives were characterized by high-trait psychopathy.Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 Similar to FPPP with ASPD, psychopathy was associated with additional criminogenic and clinical needs that can impede treatmentReference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 , Reference Dolan and Davies 25 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 suggesting that these FPPP have heterogeneous pathways to violence.

Partly underlying the abovementioned findings on heterogeneous pathways to violence, FPPP also had a mixture of strengths and weaknesses across multiple cognitive domains compared to nonforensic patients with psychosis.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 It was hypothesized that better cognitive performance may identify patients who are prone to callous and premeditated violent acts, whereas cognitive deficits may identify patients with impulsive outbursts when they are distressed.Reference Barlati, Nibbio and Stanga 21 In other studies, specific moral cognitions were shown to mediate the relationship between psychosis and violence, and the effect of cognition on violence was shown to be modified through engagement in psychosocial programming.Reference O’Reilly, O’Connell and O’Sullivan 37 , Reference Richter, O’Reilly and O’Sullivan 41 FPPP with violent behavior also varied widely in their access to employment, housing, and social support.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 Childhood trauma, adult violent victimization, and low education were consistently associated with violent offending, and similar findings have been replicated in other reviews.Reference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Iozzino, Canessa and Rucci 29 , Reference Markiewicz, Pilszyk and Kudlak 33 , Reference Markopoulou, Chatzinikolaou and Karakasi 35 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 , Reference Dean, Moran and Fahy 54 Addressing additional criminogenic needs, including social support, family, accommodation, education, employment, or vocational needsReference de Girolamo, Iozzino and Ferrari 18 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 42 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 and bolstering of protective factors, are gaining traction. Moreover, clinicians are encouraged to routinely conduct assessments and develop integrated treatment plans that are consistent with current evidence and best practices to address multiple contributors to violence.Reference Pollard, Ferrara and Lin 48 –Reference Zygmunt, Olfson, Boyer and Mechanic 51 Along this line, there is growing evidence for psychological interventions, especially cognitive-based approaches with short-term rewards, for rehabilitating offenders with antisocial behavior or substance misuse.Reference Volavka 55 –Reference Ross, Quayle, Newman and Tansey 57

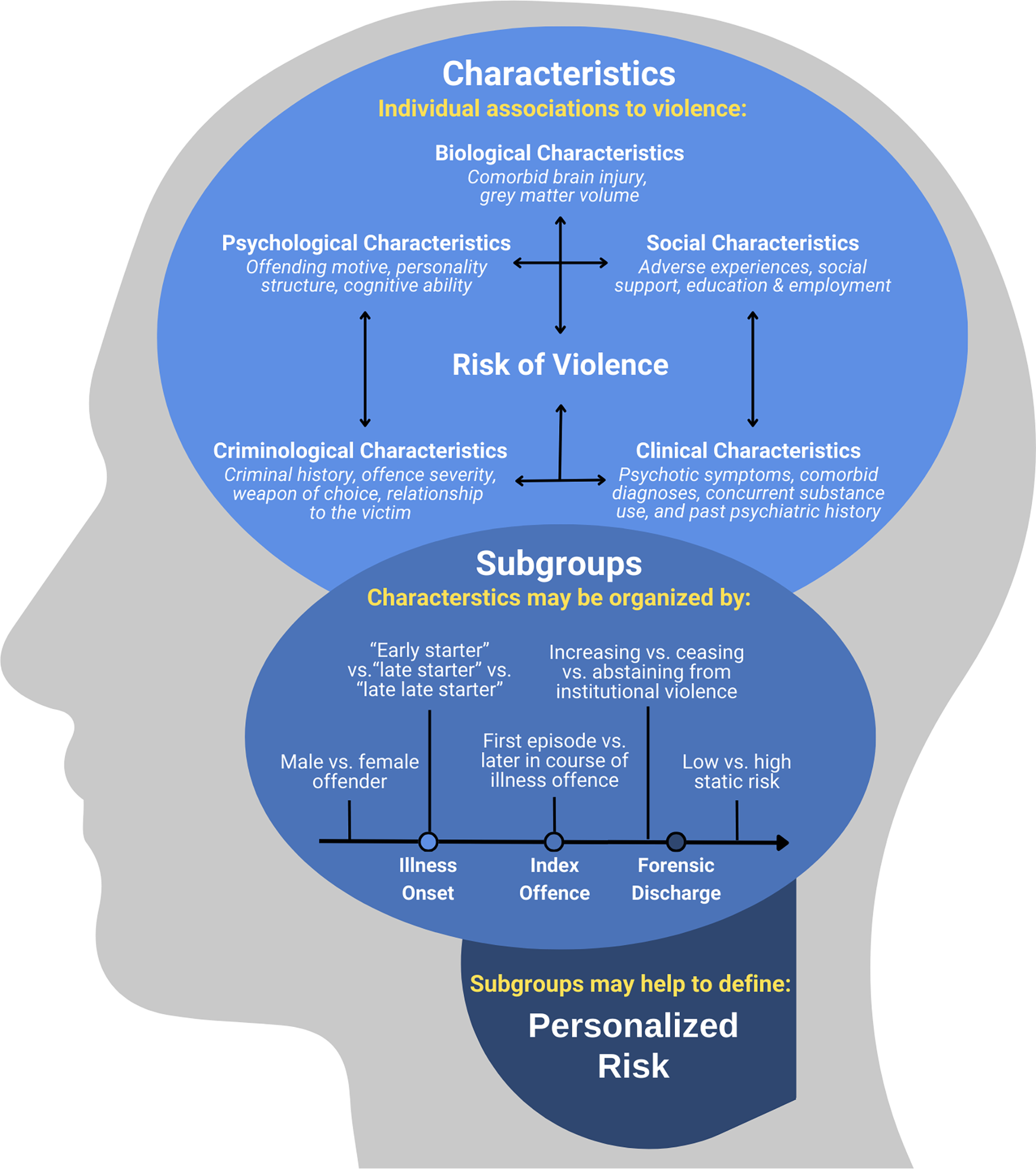

A major source of challenge in the assessment and management of violence in FPPP is the limitations associated with predicting the risk of violence reliably. Except for certain characteristics, this review found that FPPP with violent behavior was a heterogeneous group. This variability can make it difficult to assess risk, since the evidence that applies to some FPPP may be less relevant to others. For this reason, detailed history and mental status exams obtained from clinical assessments are essential for placing this evidence in context.Reference Murray and Thomson 13 While clinical prediction tools help assist clinicians in gathering appropriate data, they may have certain limitations, including focusing a panel of few risk factors with known clinical relevance.Reference Fazel, Singh, Doll and Grann 14 , Reference Singh, Serper, Reinharth and Fazel 15 Predictive models relying on few individual factors do not cohere with the view that violence can result from the combinatorial effects of many variables.Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Rose, Mamak and Goldberg 22 , Reference Battaglia, Gicas, Mamak and Goldberg 23 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Fullam and Dolan 27 , Reference Kovacević, Zarković Palijan, Radeljak, Kovac and Ljubin Golub 31 , Reference Kuroki, Kashiwagi and Ota 32 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Ružić, Frančišković and Šuković 42 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 Rather than solely identifying individual characteristics or panel of certain factors that are associated with violence, recent trends and efforts are focused toward describing subgroups of FPPP with underlying biopsychosocial similarities and risk profiles that make it easier to predict their risk for violence and personalize interventions. To accommodate for heterogeneity, prediction tools may benefit from specifying when and where to apply evidence. In particular, this review identified the strategy of stratifying FPPP into subgroups to be more accurate and clinically relevant to describing their risk. Specifically, subgroups at different times in their trajectory were identified.Reference Joubert and Zaumseil 17 , Reference Ferranti, McDermott and Scott 26 , Reference Markopoulou, Karakasi, Garyfallos, Pavlidis and Douzenis 34 , Reference Nielssen, Yee, Millard and Large 36 , Reference Penney, Marshall and Simpson 38 , Reference Penney, Morgan and Simpson 39 , Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney 44 Samples were stratified by their sex, the timing of their violent offending relative to illness onset, the timing of their index offense in their illness course, their trajectory of violent offending during admission, and their trajectory of violent offending after discharge. The resulting subgroups were more homogenous in terms of their risk and behavior than the entire sample, which may make it easier to predict and prevent future violence in each group. Clinicians may also find it more intuitive to place patients in subgroups that correspond with their pre-existing schemas instead of measuring individual risk factors. These findings are considered in the context of the ability to integrate multiple risk factors into an algorithm that helps apply recent technology for data mining to recommend future directions in clinical and research practice.Reference Hofmann, Lau and Kirchebner 28 , Reference Sonnweber, Lau and Kirchebner 45 Figure 2 includes a model of explanatory pathways for violence in FPPP based on a summary of the findings from the included reports in this review. Notably, a model summarizing risk factors for violence similar to what we did in the present study ought to be designed with some flexibility and be ‘dynamic’ to allow the integration of emerging evidence on risk factors for violence in FPPP.

Figure 2. A model on explanatory pathways for violence in FPPP.

Study limitations

This systematic review must be considered in the context of some limitations. First, the quality of the included studies was variable. Most studies acknowledged significant limitations in their methodology, including retrospective study design, small sample size, and unaccounted confounding factors. Studies with retrospective designs have limitations with establishing causal relationships, and we were unable to differentiate whether the characteristics associated with violence in FPPP act as correlates, causes, or consequences of either psychosis or violence. Again, this review included only studies conducted in jurisdictions where patients are found “not criminally responsible” or “permanently unfit to stand trial” to enter the forensic system. This definition was used to identify samples whose index offences were specifically attributed to mental illness. Second, while individual study findings were presented in quantitative terms as much as possible, we were unable to compare effect sizes or statistical significance across studies and conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity among research questions, study designs, and outcomes in the included studies. Third, our research question was intentionally broad to capture the full breadth of characteristics that have been investigated to underlie violence in FPPP. Fourth, we speculated that the variability in our findings was explained by true variation between FPPP and supported this hypothesis with studies that produced more consistent results by dividing their samples into subgroups. The population of FPPP may not be as heterogeneous as the present findings suggest, and its heterogeneity may not be resolved by stratifying the population into subgroups. Regardless, this review identified an emerging approach to risk stratification that warrants further investigation. Lastly, this review does not provide an exhaustive overview of FPPP subgroups identified in the literature. Guided by these results, future research is needed to ask more focused research questions that are suitable to meta-analyse and help identify subgroups with the greatest clinical significance to validate those discussed in this review.

Conclusion

The present review represents an effort to consolidate several areas of research on the relationship between psychosis and violence in FPPP. Consistent with previous literature, violence was related to certain identifiable biopsychosocial factors, albeit some heterogeneous findings were also identified. Some areas of heterogeneity on the findings on violence among FPPP were addressed by stratifying samples using a combinatorial model based on sex, timing of violence relative to illness onset, timing of index offense in the illness course, violent offending during admission, and violent offending after discharge. The resulting subgroups may have more predictable patterns of risks and behaviors that are associated with violence in FPPP. There is a need for high-quality future studies to replicate the clinical utility of this approach and integrate emerging evidence. For example, prospective studies with robust methodology to assess the performance of a model that stratifies FPPP into subgroups to predict violent outcomes would be necessary. Ultimately, identifying high-risk subgroups may provide an avenue to improve risk assessment and personalize interventions aimed at mitigating violence. Furthermore, this review did not capture an exhaustive list of factors associated with violence. Future research efforts on this study theme would benefit from considering more factors linked to violence in psychosis (e.g., poor insight, psychiatric comorbidity, LAI versus oral medications and aspects of the clinical environment)Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann 1 , Reference Witt, Van Dorn and Fazel 5 , Reference Elbogen and Johnson 6 , Reference Whiting, Glogowska, Fazel and Lennox 49 to support their clinical relevance in FPPP. Lastly, risk assessment, prediction, and management can also benefit from innovative application of recent advancements in data mining, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to test a combinatorial model for risk factors associated with violence in FPPP. Such innovative applications need to be operationalized and tested in future research to generate evidence for translation into practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852924000488.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Rhys Linthorst for their participation in early discussions regarding the content of this review. We would also like to thank the McMaster Health Sciences Library for assistance with developing our search strategy. We are grateful for the positive feedback received during the oral presentation of the study’s abstract at the 23rd World Psychiatry Association (WPA) World Congress in Vienna, Austria, in 2023.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: A.S., G.A.C., J.B., M.M.K., S.B., W.P., A.T.O.; Data curation: A.S., J.B., M.M.K., S.B., W.P., A.T.O.; Funding acquisition: A.S., A.T.O.; Visualization: A.S., A.T.O.; Writing – original draft: A.S., S.B., W.P., A.T.O.; Writing – review & editing: A.S., G.A.C., J.B., M.M.K., A.T.O.; Formal analysis: G.A.C., J.B., M.M.K., S.B., W.P.; Resources: G.A.C., A.T.O.; Supervision: J.B., A.T.O.; Investigation: A.T.O.; Methodology: A.T.O.; Project administration: A.T.O.; Software: A.T.O.; Validation: A.T.O.

Financial support

This work was supported by a McMaster Medical Student Research Excellence Scholarship awarded to AS.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.