On August 20, 2018, protesters in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, toppled the Silent Sam Confederate monument, which had stood on the University of North Carolina’s flagship campus since 1913. Although the statue had been a source of many protests for the better part of its existence, the 2017 white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—which stemmed from protests surrounding Confederate monuments on the University of Virginia’s campus—renewed the call for the removal of such memorials across the nation, including the Silent Sam statue. Public outrage in many places has reached a fever pitch; however, these incidents show that dismantling these divisive structures is not as straightforward as some would believe.

It is from this backdrop that the burgeoning research on Confederate monuments emerged. Scholarly and journalistic narratives surrounding monument removal come in two general forms: (1) case studies of Southern cities, counties, and other municipalities (mostly in the Deep South) that currently have or once had Confederate symbols; and (2) polling reports of people’s attitudes about these symbols. Case-study approaches allow us to appreciate more fully the rich historical and sociopolitical contexts within which Confederate monuments are erected, debated over, and (on occasion) taken down. However, this benefit often is counterbalanced by the limited generalizability of the findings. Likewise, the advantage of surveys is that they can uncover the motivations surrounding decisions to preserve monuments or let them die. When polls are large sample and nationally representative, the results expand our overall understanding and allow us to speak more generally about the complexities of monument removal. However, survey-based approaches tend to be weaker when analyzing the importance of sociopolitical and racial context. Our aim is to incorporate the strengths of both approaches into a comprehensive exploration of why some monuments have been dismantled and others remain in place.Footnote 1

Our aim is to incorporate the strengths of both approaches into a comprehensive exploration of why some monuments have been dismantled and others remain in place.

We begin by theorizing about the interconnections among race, partisanship, and institutions as predictors of monument removal. We tested the implications of this theory by supplementing the Southern Poverty Law Center’s list of “publicly supported spaces dedicated to the Confederacy” with an original dataset that captures social, racial, and political information about the locales in which these monuments are found (see www.splcenter.org/20190201/whose-heritage-public-symbols-confederacy). In so doing, we elucidate how racial politics, party dynamics, and the structure of city- and state-level governments can affect the degree to which Confederate symbols survive or perish. Moreover, our results provide meaningful answers to what has led—and will potentially lead—to the removal of Confederate monuments as well as present a paradox for those officials who may seek to bring them down. Given that many of the monuments are in Southern states with Republican vote shares, the ability of some politicians may be constrained by both the law and a desire to keep the city’s voting majority content. More broadly, this article provides greater context for the complexities of state and local government and the motivations of politicians.

RACE, POLITICS, AND CONFEDERATE MONUMENT REMOVAL

We seek to contribute to the growing literature on Confederate monuments by merging case-study with survey-based approaches. As noted previously, the former approach may focus on specific memorials, speak thematically about a set of monuments, or situate the debates about Confederate symbolism within broader arguments about the politics of the commemoration. The work of Brundage (Reference Brundage2009) comes immediately to mind. The latter approach features analyses of polling results that are sometimes complemented with survey-based experimental interventions. Interpreting patterns from several polls conducted in the summer of 2017, Edwards-Levy (Reference Edwards-Levy2017) summarized the conventional wisdom of polling research on Confederate symbols. Specifically, the journalist mentions in her report to HuffingtonPost.com that “opinions on the Confederate memorials are divided along racial lines but to an even greater degree along political ones.” We show that applying these individual-level insights to aggregate-level research provides a fertile foundation from which to build a theory of monument removal.

Racial Predictors of Confederate Monument Removal

Numerous studies link individuals’ attitudes about Confederate monuments to racial considerations. For example, by merging results from a nationally representative survey with polls of Georgia and South Carolina residents, Strother, Piston, and Ogorzalek (Reference Strother, Piston and Ogorzalek2017) demonstrated that anti-black sentiments can strengthen whites’ endorsement of Confederate symbols (see also Clark Reference Clark1997). Orey (Reference Orey2004) found something similar in his analyses of white survey respondents in Mississippi. Using an experiment that was embedded within a survey of residents from the state of Georgia, Hutchings, Walton, and Benjamin (Reference Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin2010) found that rank-and-file blacks (i.e., those in the electorate) tend to be less supportive of Confederate symbols than whites. Alderman (Reference Alderman2010), Hodder (Reference Hodder2016), and Johnson (Reference Johnson2005) provided historical evidence that illustrates the degree to which the decisions of black elites (e.g., elected officials and community organizers) have been instrumental in the quest to tear down Confederate monuments.

In their studies about the impact of the South’s heritage of slavery on contemporary political attitudes and actions, Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018) combined archival research with (nonexperimental) polling data to demonstrate that many of these monuments were erected when leaders of Southern states were fighting to curtail the rights for black citizens.Footnote 2 Furthermore, Walton (Reference Walton1972) found that race-based organizations can help communities of color translate their preferences into policy. Research by Alderman (Reference Alderman2010), Hodder (Reference Hodder2016), and Johnson (Reference Johnson2005) confirmed that in locations where organizations work on behalf of blacks, there is an increased capacity to have Confederate symbols removed. The potential impact of race leads us to expect the following:

Proposition 1: Whether a Confederate monument is removed depends on the amount of anti-monument pressure that blacks (and racially progressive allies) can exert.

Political and Institutional Predictors of Confederate Monument Removal

An alternative perspective credits the current and future status of a city’s Confederate monuments to political and institutional rather than racial factors. Clearly, ideology and partisanship also play an important part in monument removal: research consistently shows that those who self-identify as Republicans or conservatives are more favorable toward Confederate symbols than their liberal Democratic counterparts (Cooper and Knotts Reference Cooper and Knotts2006; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears2005). Moreover, the argument that partisanship factors prominently in the removal of Confederate monuments comports with existing work on the relationship among racial attitudes, partisanship, and living in the South. Valentino and Sears (Reference Valentino and Sears2005) showed that since the Civil Rights era, white Southerners from states comprising the “Old Confederacy” have experienced a significant swing to the Republican Party. This partisan change occurs only in these states, and their residents also exhibit higher feelings of racial conservatism relative to people in other parts of the country (Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears2005, 678). The persistence of these beliefs is discussed further by Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018) when they explain that after the Civil War, Southern whites passed down their racially conservative political viewpoints through the generations. As posited by Valentino and Sears (Reference Valentino and Sears2005), these racial attitudes map onto their affiliation with the Republican Party. These findings are buttressed by the experimental results of Hutchings, Walton, and Benjamin (Reference Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin2010), which reveal that Democratic identification among men in their sample decreased significantly, showing how racially explicit appeals influence partisan attachment for white Southerners. Thus, the relationship among being in the South—where many Confederate monuments are located (figures 1–4)—racial attitudes, and partisanship is made clear in existing work. This relationship provides a solid foundation on which we build our argument that partisan leaning will influence the likelihood of monument removal.

Figure 1 Support for Hillary Clinton in 2016—Deep Southern State Removal

Figure 2 Support for Hillary Clinton in 2016—Mid-Atlantic State Removal

Figure 3 Support for Hillary Clinton in 2016—Border-State Removal

Figure 4 Support for Hillary Clinton in 2016—Union-State Removal

In addition to shedding light on the institutional restrictions that may preclude (or, at a minimum, make difficult) the dismantling of Confederate monuments, party dynamics elucidate the political landscape of the communities that have these monuments. More specifically, the share of the Election Day vote garnered by the 2016 presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, serves as a proxy to indicate how pro-Democratic an area is.Footnote 3 Figures 1 and 2 display the county-level support for Clinton across states within the Deep South and the Mid-Atlantic regions (i.e., the two areas of the country with the most Confederate statues). Figures 3 and 4 show removals in the Border States and the Union States. White dots on the figures indicate jurisdictions in which Confederate monuments have been dismantled. As the maps show, these statues were in counties that voted overwhelmingly in favor of Clinton. This comports with our finding that the degree to which a jurisdiction leans Democratic is a strong predictor of whether a Confederate monument will be dismantled.

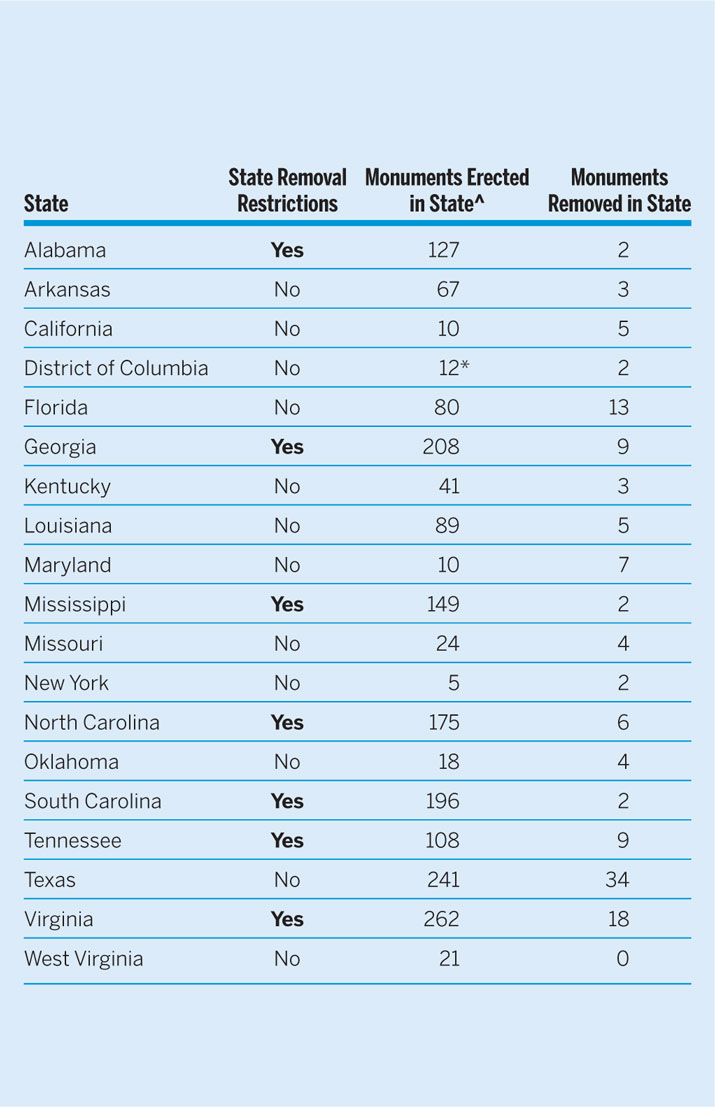

In addition to Southern heritage and political orientation, studies demonstrate that institutional constraints can influence monument removal. For example, many Confederate statues exist in states that have passed legislation to curtail their dismantling. Table 1 lists states in which five or more Confederate monuments were erected. Among these 18 states and the District of Columbia, seven have passed such laws. Moreover, of the 130 monuments that have been removed, 82 (63%) are in states that have not passed such legislation.

Table 1 List of States with Confederate Statues and Whether State Removal Restrictions Exist

Notes: ^This list was truncated to include only states that, as of August 21, 2018, were home to five or more Confederate monuments.

* The monuments in the District of Columbia are located in the US Capitol, which—although located in Washington, DC—sits on federally owned land.

This pattern is consistent with our findings that the likelihood of these restrictions being circumvented is greater if Democratic support in the region is high. In addition to shedding light on the institutional restrictions that may preclude or make difficult the dismantling of Confederate monuments, party dynamics elucidate the political landscape of the communities that have them. More specifically, Leib, Webster, and Webster (Reference Leib, Webster and Webster2000) and Levinson (Reference Levinson1994) demonstrated that many states enacted legislation that makes it more difficult for local governments to tear down Confederate monuments. These provisions can range from the requirement of a two-thirds legislative vote for monument removal (e.g., in South Carolina); to a state-level historical commission with both oversight authority and veto power over the status of Confederate monuments (e.g., in Tennessee); to laws that directly prevent the defacing and/or otherwise harming of “objects of remembrance,” which are in effect in Alabama, North Carolina, and Virginia (Bliss and Meyer Reference Bliss and Meyer2017; Kaleem Reference Kaleem2017; Subberwal Reference Subberwal2017). Finally, in a recent survey experiment, Johnson, Tipler, and Camarillo (Reference Johnson, Tipler and Camarillo2019) found that voters are more supportive of monument removal when those decisions are made by voters via ballot initiatives rather than city councils. These studies suggest that institutional barriers and governing structures can explain what happens to monuments. Thus, we anticipate that:

Proposition 2: Whether a Confederate monument is removed depends on how anti-monument a municipality is (i.e., how politically appealing or feasible it is for its residents and leaders to push for such removals, absent state restrictions).

RACE AND POLITICS AS INTERSECTING PATHWAYS TO MONUMENT REMOVAL

Thus far, we conceive of monument removal as being a function of either race or politics. We move beyond either/or characterizations to consider the potentially conditional impact of these variables. As Browning, Marshall, and Tabb (Reference Browning, Marshall and Tabb1984) noted, social movements require both grassroots agitation and favorable “opportunity structures” to be successful. Our argument is inspired by social-movement scholars because we attribute the general finding in survey-based approaches (i.e., that politics matters more than race regarding monument removal) to the fact that survey researchers have yet to sufficiently explore the interactive influence of race and politics. After all, race may not matter if the politics in a municipality are not conducive to removing Confederate monuments. Likewise, when the politics of an area are progressive enough, then race can have an even greater impact.

Proposition 3: The ability of racial considerations to influence Confederate monument removal depends on the degree to which the political context supports such removals.

After all, race may not matter if the politics in a municipality are not conducive to removing Confederate monuments.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The original data collected for this article supplements the Southern Poverty Law Center’s list of Confederate monuments with information gleaned from sources including CNN.com, 538.com, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. Our dataset records, among other factors, the number of Confederate monuments a city currently has, the year in which they were erected, the types of monuments found in the cities (e.g., plaques and statues), and their location (i.e., on private versus government property). This data-collection processFootnote 4 also required us to obtain demographic characteristics of the specific cities, such as race of the mayor; composition of the local governing body (e.g., city council or board of commissioners); and whether a civil rights organization was present in the area or, specifically, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).Footnote 5 As noted previously, we are interested in whether monuments are removed. Our analyses utilized a sample of 1,800 monuments.

We explored the complex interplay among racial considerations, local-government structures, civic characteristics, and monument removal by estimating the following regression model, where set x contains all predictors; the dependent variable (y) is a binary measure of monument status (1=removed, 0=otherwise); the coefficients for each predictor (β) result from minimizing the estimate’s error (ε); and the functional form is such that for each monument, the predicted value of y is derived by:

Past research informed which predictors we included in x. Specifically, to account for the influence of racial context, we included measures for a city’s racial composition, both in the electorate (i.e., operationalized as the proportion of black residents) and in elected office (1=black mayor present, 0=no black mayor). We also assessed a city’s black organizational capacity by keeping track of whether the NAACP established a local chapter in the area (1=yes, 0=no). Furthermore, we controlled for the impact of additional institutional factors such as Democratic vote share (i.e., the proportion of a city that voted for a Democratic candidate in the 2016 election)Footnote 6 and whether state-level laws that restrict dismantling exist (1=state restricts local government, 0=otherwise). These are the key independent variables that drove our expectations. Control variables include the proportion of black residents in a city and a regional indicator of whether a state was a former member of the Confederacy (see table 2 for full models).

Table 2 Modeling the Likelihood of Removing Confederate Monuments—Main Effects

Source: 2017 Confederate Monuments Database.

Notes: Estimates are logistic regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is a binary measure recording whether a Confederate monument(s) was removed from a city (0=no; 1=yes). +p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

ANALYSES AND RESULTS

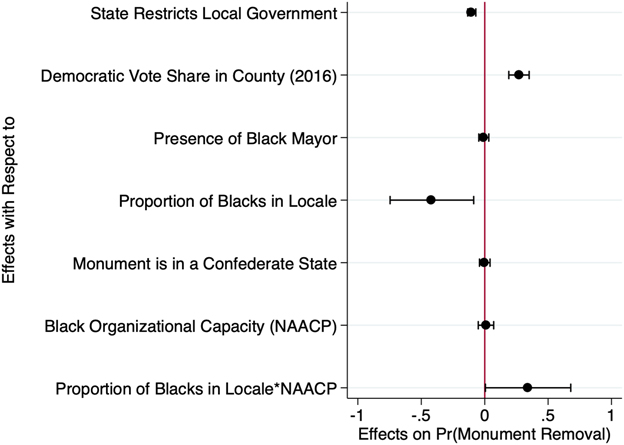

Table 2 and figure 5 examine the effects of various independent variables on the likelihood of monuments being removed. Most notably, the Democratic vote share in the county plays a large role—both statistically and substantively—in whether a monument will be taken down (i.e., removal is 27 percentage points more likely: 0.001). Figure 5 also shows that statewide restrictions make it more difficult to dismantle monuments in a given jurisdiction (i.e., removal is 10 percentage points less likely). These results provide evidence that political factors matter. Figure 5 also shows that the proportion of African Americans in a locale actually led to a statistically significant decrease in the likelihood of monument removal (i.e., 41 percentage points: p<0.05). Moreover, the presence of an NAACP chapter alone did not increase the likelihood that a monument(s) will be removed. Most important, the interaction between the size of the black population and the presence of an NAACP chapter is positive and significant (p<0.05). Substantively, this means that in places where the black population is significant and there is an NAACP chapter, there is a 34-percentage-point increase in the likelihood of monument removal. This is the crux of our argument. It is not the size of the black population alone or the presence of the NAACP alone. It is the combined influence of both.

It is not the size of the black population alone or the presence of the NAACP alone. It is the combined influence of both.

Figure 5 Modeling the Likelihood Confederate Monument Removal—Main Effects

Notes: Estimates are logistic regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. We suppressed the constant. The dependent variable is a binary measure recording whether a Confederate monument(s) was removed (0=no; 1=yes).

DISCUSSION

This article explores the racial, political, and institutional factors that best explain the dismantling of Confederate monuments across the country. Thus far, contemporary work has provided little evidence to explain why some monuments have come down whereas others have not. To accomplish this task, we assembled an original dataset that allowed us to not only account for the demographic tapestry of the jurisdictions that are home to Confederate monuments—such as their racial and partisan compositions—but also the institutional landscape of the states in which these cities are located, both of which are critical pieces of the monument-dismantling puzzle. When we considered racial and political factors, we found that the probability of a monument being dismantled is greater where the black population is significant and there is an NAACP chapter. We also found evidence of monument removal in Democratic areas conditional on whether statewide laws constrained local actors from dismantling the monuments.

To date, the public discourse surrounding the dismantling of monuments has focused primarily on the sociohistorical racial contexts in which they were erected, attitudes toward Confederate monuments, and results from experiments. Our findings lead us to believe that it is prudent to consider both the racial and the institutional contexts that surround these structures. We hope that future research will continue to consider the roles that race and institutions play in constraining both elite- and individual-level behavior, particularly in matters for which support for an issue seemingly has reached a point of general consensus.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519002026