Introduction

The Atlantic Forest has been almost destroyed by 500 years of human exploitation (Dean Reference Dean1995, Joly et al. Reference Joly, Metzger and Tabarelli2014), and what remains of its original formation is heavily fragmented into thousands of small and isolated forest patches (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Metzger, Martensen, Ponzoni and Hirota2009). Due to these impacts, a significant portion of its biodiversity has been irrevocably lost, but the biodiversity that persists makes the Atlantic Forest one of the world’s five most important biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al. Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000, Joly et al. Reference Joly, Metzger and Tabarelli2014). The drastic reduction in forest cover of the Atlantic Forest is largely due to logging and the establishment of agricultural areas (Galindo-Leal & Câmara Reference Galindo-Leal and Câmara2005). Most of what is left of the Atlantic Forest in Brazil is concentrated in areas with steep slopes, where agriculture is difficult, such as the Serra do Mar, Paranapiacaba and the Mantiqueira areas (Tabarelli et al. Reference Tabarelli, Aguiar, Ribeiro, Metzger and Peres2010). The only exception in Brazil, where a large Atlantic Forest remnant occurs in less rugged terrain, is ParNa Iguaçu (Iguaçu National Park), created in 1939 around the iconic Iguaçu Falls, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (UNESCO 2022) and one of the seven natural wonders of the world due to its scenic beauty (N7W 2022). ParNa Iguaçu along with protected and unprotected areas in the province of Missiones (Argentina) form one of the largest remnant patches of Atlantic Forest, at almost 1 million ha (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Metzger, Martensen, Ponzoni and Hirota2009).

The scenic beauty of the Iguaçu Falls is an example of an ecosystem service that natural ecosystems provide to humans free of charge (Tallis & Kareiva Reference Tallis and Kareiva2005). However, ParNa Iguaçu represents much more than just its falls, with various other important ecosystem services provided by its 185 000 ha. ParNa Iguaçu boasts a vast biodiversity: 619 known species of vascular plants (Trochez et al. Reference Trochez, Tasistro, Duarte, de Almeida, Ferreira, Vendruscolo and Lima2017), 335 bird species (Straube et al. Reference Straube, Urben-Filho and Cândido Junior2004), 102 mammals (Brocardo et al. Reference Brocardo, da Silva, Feraciolli, Cândido Junior, Bianconi and Moraes2019), 12 amphibians (ICMBio 2018), 48 reptiles (ICMBio 2018) and invertebrates including 89 species of butterflies (Fianco et al. Reference Fianco, Szinwelski and Faria2022), 135 species of Cerambycidae beetles (Barros et al. Reference Barros, Fonseca, Jardim, Vendramini, Damiani and Julio2020) and over 800 known species of other invertebrates (ICMBio 2018). All of these numbers are undoubtedly underestimates.

In Brazil, the conservation and preservation of natural habitats and, consequently, the maintenance of ecosystem services are incentivized through payment for environmental services by transferring financial resources from the state governments to the municipalities (counties). The Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (ICMS; or Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services) is a state tax, the implementation of which is governed by Article 155 of the Federal Constitution (Brazil 1988). In the state of Paraná, 25% of the amount collected from this tax is transferred to municipalities according to a Municipality Participation Index, and state legislation stipulates that 5% of this transfer be allocated to municipalities that have water supply catchment areas for neighbouring municipalities, conservation units or Indigenous lands. This gave rise to the ICMS-e (ecological ICMS), which was pioneered by Paraná (Paraná 1991) and serves as a model now adopted by almost all Brazilian states. In 2021, Paraná transferred almost 478 million reais (∼93 million USD – conversion as of 20 May 2024) to Paraná municipalities in ICMS-e, of which the 13 municipalities bordering ParNa Iguaçu received 29 million reais due to the National Park (IAT 2022). This amount can increase with the improvement or expansion of municipal conservation areas or can decrease due to factors such as the reduction, extinction or recategorization of conservation units (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, Penna and Araújo2014). Thus, investment in the persistence of protected areas and water catchment areas is a way to ensure the maintenance of various ecosystem services, biodiversity, environmental health, human well-being and the economic health of municipalities.

However, despite being iconic and environmentally and economically important, ParNa Iguaçu has been facing serious threats and pressures, including the processing of two bills directly affecting the National Park that are advancing through committees in the National Congress: PL 7123/2010 (Maria Reference Maria2019) and PL 984/2019 (Couto Reference Couto2010), setting a precedent that may affect other conservation units (protected areas for biodiversity). Both bills propose changes to Law 9985/2000, which establishes the National System of Nature Conservation Units, or SNUC (Brazil 2000), to establish a new type of protected area: the ‘park-road’. This new type of protected area would be a ‘sustainable use’ conservation unit under the terms of Article 14 of Law 9985/2000, reducing the current level of conservation and protection of ParNa Iguaçu. These bills propose the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road along a route through secondary forest with over 20 years of regeneration, where, prior to 2001, a road cut through the National Park for 17.5 km between the municipalities of Serranópolis do Iguaçu and Capanema (Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Sobral-Souza, Kuczach, Brocardo, Sperber and Fearnside2020).

Such proposals imply environmental damage from National Park fragmentation, wildlife roadkill and deforestation for road construction, as well as potentially increasing illegal activities within the National Park (Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Bertrand, Martello, Brocardo and Cunha2022). They would also cause significant economic losses to the region (Ortiz Reference Ortiz2009). A reduction in either the area of a conservation unit or its protection status would result in decreased transfers of ICMS-e to the affected municipalities, harming the region’s development instead of improving it, the latter being what the local population generally believes would occur. Especially in the municipalities of Serranópolis do Iguaçu and Capanema, residents have often been influenced by political leaders who argue in favour of opening the Caminho-do-Colono road using discourse that has been characterized as fallacious and simplistic (Garcia & Baptiston Reference Garcia and Baptiston2014, Kropf & Eleutério Reference Kropf and Eleuterio2015). In contrast, the national view is against the road’s opening; in a poll conducted by the Chamber of Deputies, 95% of those interviewed were against opening the road (Câmara dos Deputados 2023). Nevertheless, Bill 7123/2010 was approved by the Chamber of Deputies (G1 2013) and is under review in the Federal Senate, and Bill 984/2019 had its urgency regime approved by 315 votes in favour versus 180 against (G1 2021) and is awaiting consideration by the plenary of the Chamber.

The present study investigates the economic and environmental implications of reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road through ParNa Iguaçu. We assessed the importance of ParNa Iguaçu for biodiversity conservation and for the economy of the municipalities in the region through payment for environmental services as well as the potential economic impacts of reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road. The main objective is to assess the impact of proposed legislative changes on the conservation of the National Park and its economic importance to local municipalities through ICMS-e. Despite the recognized importance of protected areas, there is limited empirical evidence on the economic impacts of opening or closing roads in these areas, particularly in the context of the Atlantic Forest. We evaluated the National Park’s contribution to maintaining native vegetation cover in the region, testing the hypothesis that, outside its boundaries, the amount of native forest decreased significantly between 1985 and 2020 due to deforestation, while inside the National Park the amount of forest remained stable. We estimated the economic importance of ParNa Iguaçu for the municipalities either overlapping or neighbouring the National Park, testing the hypothesis that ICMS-e significantly contributes to the economic performance of these municipalities and that the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road would have negative impacts on this performance. Finally, we calculated whether the economic performance of the municipalities was affected by the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road, testing the hypothesis that the road closure did not affect the economic performance of the municipalities or the region. Understanding the consequences of such legislative actions is crucial for informing policy decisions that balance conservation and development goals in biodiversity hotspots such as the Atlantic Forest.

Materials and methods

Study area

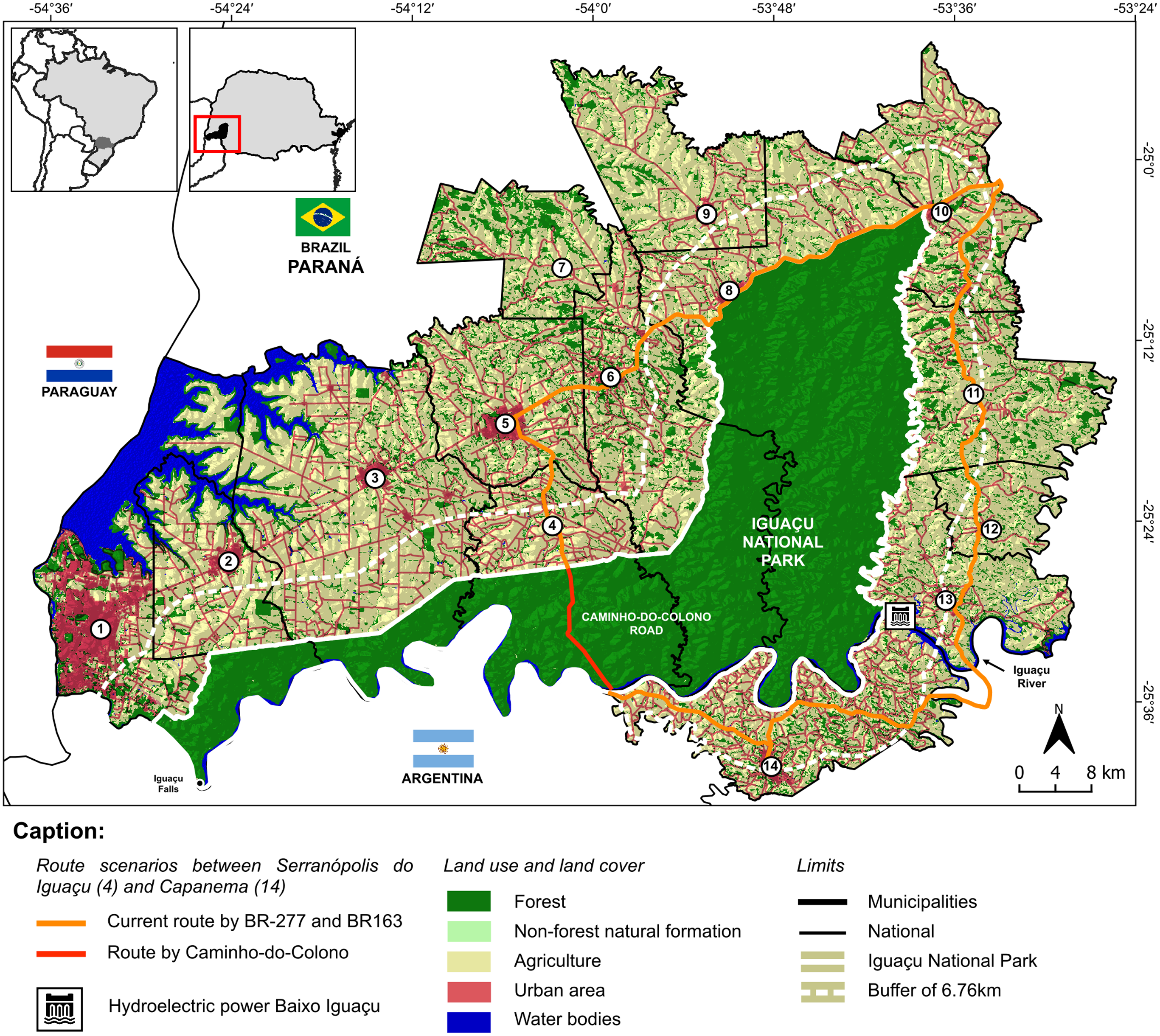

ParNa Iguaçu was created by Decree 1035/1939 and expanded by Decrees 6506/1944 and 6587/1944, with its current territorial boundaries and area (185 262.00 ha) defined by Decree 86,676/1981, which excluded 1400 ha in the northern portion and included the Iguaçu River as part of the National Park (Brazil 1939, 1944a,b, 1981). ParNa Iguaçu is almost completely surrounded by an agricultural matrix of soybeans, corn and wheat (Fig. 1), and it has two important routes for transportation of people and goods: the BR-277 and BR-163 highways. These highways would continue to be the transportation routes for agricultural commodities from the municipalities bordering the National Park, even if the Caminho-do-Colono road were to be reconstructed, as the proposed road would not shorten the route to export ports. Outside of the National Park, the few forest fragments in the region are scattered and small. ParNa Iguaçu has a subtropical climate (Cfa in the Köppen classification), with an average annual temperature of 21°C and 1807 mm of rainfall at the lowest altitude of the National Park (minimum 140 m in Foz do Iguaçu) and an average temperature of 19.9°C and 1933 mm of precipitation at the highest altitude (750 m in Céu Azul; Alvares et al. Reference Alvares, Stape, Sentelhas, Gonçalves and Sparovek2013). The topography is flatter in the western part of the National Park, with gently sloping hills, while the eastern and northern parts have more rugged terrain (Salamuni et al. Reference Salamuni, Salamuni and Rocha2022). The National Park is located in the lower Iguaçu basin, and its drainage network is composed of tributaries on the right bank of this river. The Iguaçu River has six hydroelectric dams, the most recent of which is only 500 m from the eastern border of the National Park, significantly impacting the water regime. Six municipalities have territory within the National Park boundaries (Foz do Iguaçu, São Miguel do Iguaçu, Serranópolis do Iguaçu, Matelândia, Céu Azul and Capanema), in addition to eight municipalities neighbouring the National Park (Santa Terezinha de Itaipu, Medianeira, Ramilândia, Santa Tereza do Oeste, Vera Cruz do Oeste, Lindoeste, Santa Lúcia and Capitão Leônidas Marques; Fig. 1). The municipality of Ramilândia was not included in the analyses of ICMS-e and economic performance because it does not receive any ICMS-e resources from ParNa Iguaçu.

Figure 1. Map of the study region covering ParNa Iguaçu and its neighbouring municipalities: (1) Foz do Iguaçu; (2) Santa Terezinha do Itaipu; (3) São Miguel do Iguaçu; (4) Serranópolis do Iguaçu; (5) Medianeira; (6) Matelândia; (7) Ramilândia; (8) Céu Azul; (9) Vera Cruz do Oeste; (10) Santa Tereza do Oeste; (11) Lindoeste; (12) Santa Lúcia; (13) Capitão Leônidas Marques; (14) Capanema.

Importance of ParNa Iguaçu for maintaining native vegetation cover

To assess the importance of ParNa Iguaçu to maintaining native vegetation cover, we first defined the area for analysis using the polygon of the National Park’s territorial boundaries available on the website of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio; ICMBio 2022). To assess the regional context of land use and land cover outside the National Park boundaries, we defined a buffer of 6.76 km (Fig. 1). This buffer was drawn so that both polygons, one representing the National Park and the other representing the surrounding region, had the same area (169 856.47 ha). To test the hypothesis that the amount of native forest decreased in the region surrounding the National Park while it remained stable within it, we used deforestation data provided by the ‘Deforestation and Regeneration’ database on the MAPBIOMAS 6.0 platform (MAPBIOMAS 2022) for the period from 1988 to 2019, and clipped it to the study area. From the rasters downloaded for each year, we extracted information on the area occupied by native vegetation within the National Park boundaries and for the surrounding region. With these data, we constructed a linear regression model, with a Gaussian distribution, having the area occupied by native vegetation as the response variable (y-axis), year (1988–2019) and location (inside and outside the National Park), as well as the interactions between these terms, as predictor variables (x-axis).

Importance of ParNa Iguaçu for the economy of the municipalities

To test the hypothesis that ICMS-e significantly contributes to the economic performance of municipalities within and adjacent to ParNa Iguaçu, we used economic data from the Instituto Paranaense de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (IPARDES; IPARDES 2023). We employed annual ICMS-e data, disbursed to municipalities (Capanema, Céu Azul, Foz do Iguaçu, Matelândia, São Miguel do Iguaçu, Serranópolis do Iguaçu, Santa Lúcia, Capitão Leônidas Marques, Lindoeste, Vera Cruz do Oeste and Medianeira), along with municipal revenue and expenditure data for each of these municipalities. The ICMS-e data used in this stage are specifically related to values derived from the presence of ParNa Iguaçu, considering the National Park’s own area plus any surrounding areas, such as Riparian Forests, Permanent Preservation Areas and Legal Reserves (if applicable), as per Annex III of the Instituto Ambiental do Paraná (IAP) Directive (IAT 1998). This exclusion removes ICMS-e values originating from other conservation units. The metric used to represent the economic performance of the municipalities was the ‘Liquidity Index’ (LI), estimated as the ratio of revenues to expenses of the municipalities, where values greater than 1 indicate a surplus and values less than 1 indicate a deficit in public accounts. To obtain the LI values with and without ICMS-e, we subtracted the ICMS-e value from the revenue of each municipality for each year from 1998 to 2021 (Table S1). The period from 2012 to 2014 was not considered due to a lack of available data on the disbursement from each conservation unit to each municipality. With these observations, we conducted a Wilcoxon test for each municipality, adjusting LI as the response variable (y-axis) and revenues with ICMS-e and without ICMS-e as predictor variables (x-axis).

Impacts of reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road on municipal economies

To test the hypothesis that the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road might impact the transfer of ICMS-e to municipalities due to the reduction in conservation quality scores of ParNa Iguaçu in the ICMS-e calculation table, we estimated the potential impacts of reopening this road on these scores. At this stage, we only used ICMS-e values from ParNa Iguaçu, disregarding values from surrounding areas, because only the area of ParNa Iguaçu would be affected by the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road. The biodiversity ICMS-e for a conservation unit (CU) in a given municipality is calculated considering the following parameters: (1) the municipality’s area; (2) the area of the conservation unit within the municipality; (3) a basic conservation factor (FCb), defined for federally owned units as 0.70 if the unit was created after the municipality’s emancipation and as 0.35 if before; (4) the variation of the current year’s CU quality score compared to the previous year (∆Quc), which cannot exceed 0.55 for federally owned CUs, calculated based on an evaluation table covering various factors such as threats and aggression (item V; IAT 2020a, 2020b); and (5) weighted score, where a value of 1 represents federally owned CUs and values below this represent lower hierarchies of conservation units (e.g., state, municipal CUs). Details and examples of ICMS-e calculation formulas are presented in Appendix S1. The result of the change in ∆Quc can be at most an increase or loss of 45% of the transfer regarding the CU, either by an increase or a decrease in the quality score in the calculation table. The reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road may directly affect item V (threats and aggression facing the CU). However, projecting the exact value of the score to be reduced if the road is reopened is challenging because it depends on the evaluation by the responsible agency – potentially even being completely removed, as per Article 18 of IAP Ordinance 263 of 28 December 1998 (IAT 1998). Thus, for municipalities where the withdrawal of ICMS-e would significantly impact the LI, we estimate the loss of score at different values (0.45, 0.25 and 0.10), resulting in different percentages of ICMS-e loss (45%, 25% and 10%, respectively), and then we subtracted this lost ICMS-e from the revenue for each year and updated the LI values. With these data, we conducted Wilcoxon tests for each municipality, adjusting LI as the response variable (y-axis) and the loss percentage groups (45%, 25%, and 10%) as predictor variables (x-axis), comparing each loss group with the reference group in which there is no ICMS-e loss.

According to Item II of Article 16 of IAP Ordinance 263 of 28 December 1998, part of the area of a CU may be considered to have unsatisfactory physical quality due to insufficient characteristics for its being fully identified with the management category of the respective area (IAT 1998). This may result in subtracting the area of the CU considered within the municipality. Thus, we estimated the LI with the reduced ICMS-e according to the percentage loss of quality score (45%, 25% and 10%) due to the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road in different scenarios of area loss exclusively from ParNa Iguaçu, without considering surrounding areas, in the municipality of Serranópolis do Iguaçu: (A) without loss in the calculation area; (B) with loss of the Caminho-do-Colono road route area considering a strip of 12 m by 17.5 km (–25.6 ha); (C) with loss of the route area plus a 100-m buffer (–200.6 ha); (D) with loss of the route area plus a 1.5-km buffer – regarding the edge effect on vegetation biomass reported by Chaplin-Kramer et al. (Reference Chaplin-Kramer, Ramler, Sharp, Haddad, Gerber and West2015; –2650.6 ha); and (E) with loss of the route area plus the area susceptible to increased illegal activities (Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Bertrand, Martello, Brocardo and Cunha2022; –10 025.6 ha). As the CU area used in the calculation and the ∆Qua data for all years are not available, we first calculated all scenarios with the data from 2021, estimated a percentage change in each scenario and applied this percentage reduction for the remaining years. With these data, we conducted Wilcoxon tests for each municipality, with LI as the response variable (y-axis) and the percentage loss groups (45%, 25% and 10%) as predictor variables (x-axis), comparing each loss group with the reference group without an increase in ICMS-e.

The economic performance of municipalities before and after the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road

To test the hypothesis that the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road did not affect the economic performance of municipalities, we used historical economic data (1980–2021) on municipal revenues and expenses available from IPARDES (IPARDES 2023; Table S2). We conducted a Wilcoxon test for each municipality, where the LI metric described above was the response variable (y-axis) and the period when the road was open (1980–2000) and the period since its closure (2001–2022) were the explanatory variables (x-axis). Finally, we evaluated the effect on the regional economy, considering the sum of revenues and expenses from all municipalities, with and without ICMS-e and before and after the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road, also using Wilcoxon tests. To ensure the robustness of the results, given that the period from 1980 to 2022 was marked by some economic recessions in Brazil, we tested for correlation between municipal LIs and the variation in the Brazilian gross domestic product (GDP) during this period – available from the Time Series Management System of the Central Bank (BCB 2023). However, no significant correlation was found (Table S3).

Results

Importance of ParNa Iguaçu for maintaining native vegetation cover

Due to deforestation, the amount of native forest outside the National Park boundaries significantly decreased between 1985 and 2020, while within the National Park the amount of native forest remained virtually unchanged (F = 172.35, p < 0.001; Fig. S1). Over the 31-year period, ParNa Iguaçu retained 95.6% of its area covered by native vegetation. Conversely, the native vegetation cover outside the National Park, which was 13.18% (20 468.65 ha) in 1988, decreased to 9.59% (14 884.32 ha) during the evaluated period. The area outside the National Park lost 27.28% or 5584.33 ha of its native vegetation over the 31 years.

Importance of ParNa Iguaçu for the economy of the municipalities

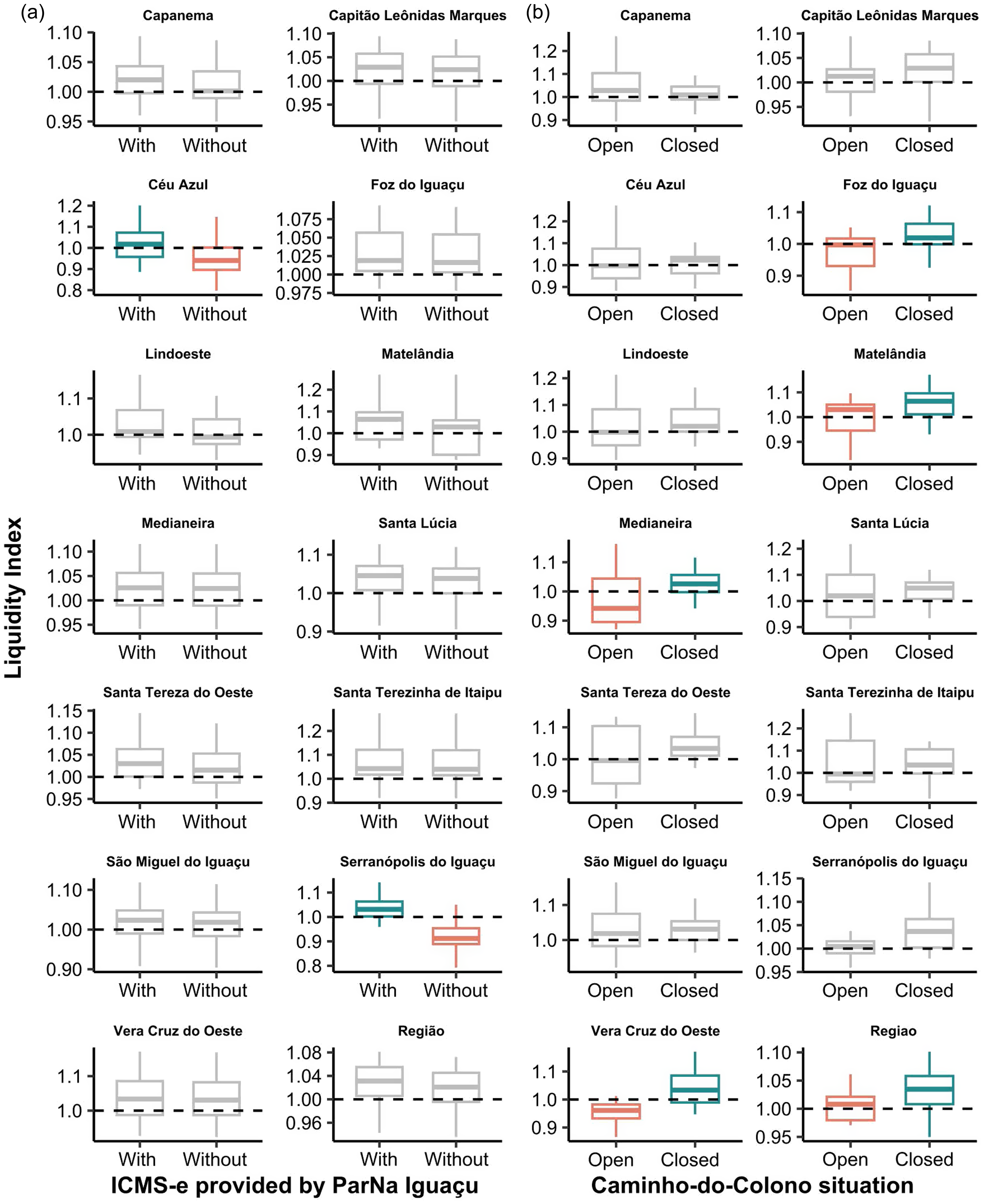

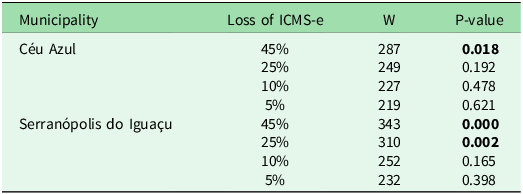

Considering the 13 municipalities either overlapping or neighbouring ParNa Iguaçu, the ICMS-e generated by this CU significantly contributes to the LI of the municipalities of Serranópolis do Iguaçu (W = 388, p < 0.001) and Céu Azul (W = 293, p = 0.011; Fig. 2a & Table 1). The withdrawal or loss of ICMS-e resources transferred by the state of Paraná to these municipalities would generate a deficit in public accounts, with LI reductions from 1.03 to 0.91 for the municipality of Serranópolis do Iguaçu and from 1.02 to 0.94 for Céu Azul (Fig. 3a).

Figure 2. Liquidity Index values of the municipalities overlapping or neighbouring ParNa Iguaçu. (a) Impact of the withdrawal of ecological Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (IMCS-e) on the Liquidity Index values of municipalities. (b) Economic performance of the municipalities and the region in the period when the Caminho-do-Colono road was open (1980–2001) and since its closure (2001–2022). Grey boxplots represent municipalities whose Liquidity Index values did not show significant differences.

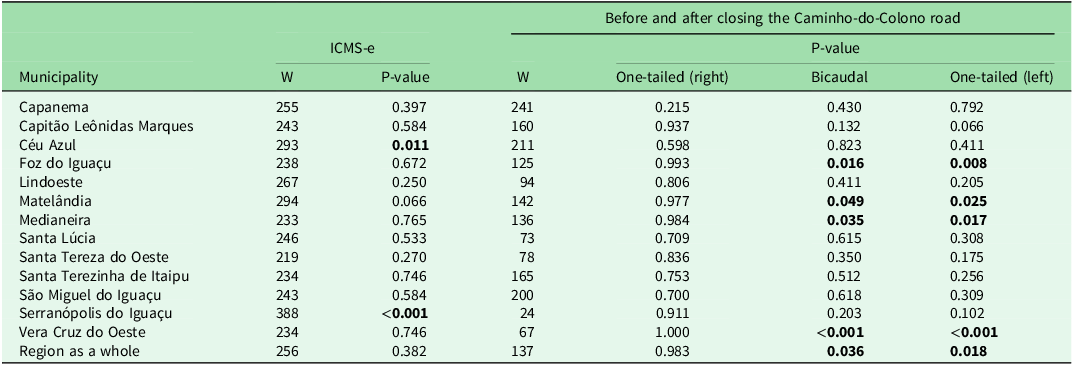

Table 1. Wilcoxon test results for scenarios with and without ecological Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (ICMS-e) and periods when the Caminho-do-Colono road was open (1980–2001) and since its closure (2001–2022). The one-tailed test (right) indicates that the Liquidity Index was higher when the Camino-do-Colono road was open, whereas the one-tailed test (left) indicates the opposite. Values in bold indicate statistically significant values.

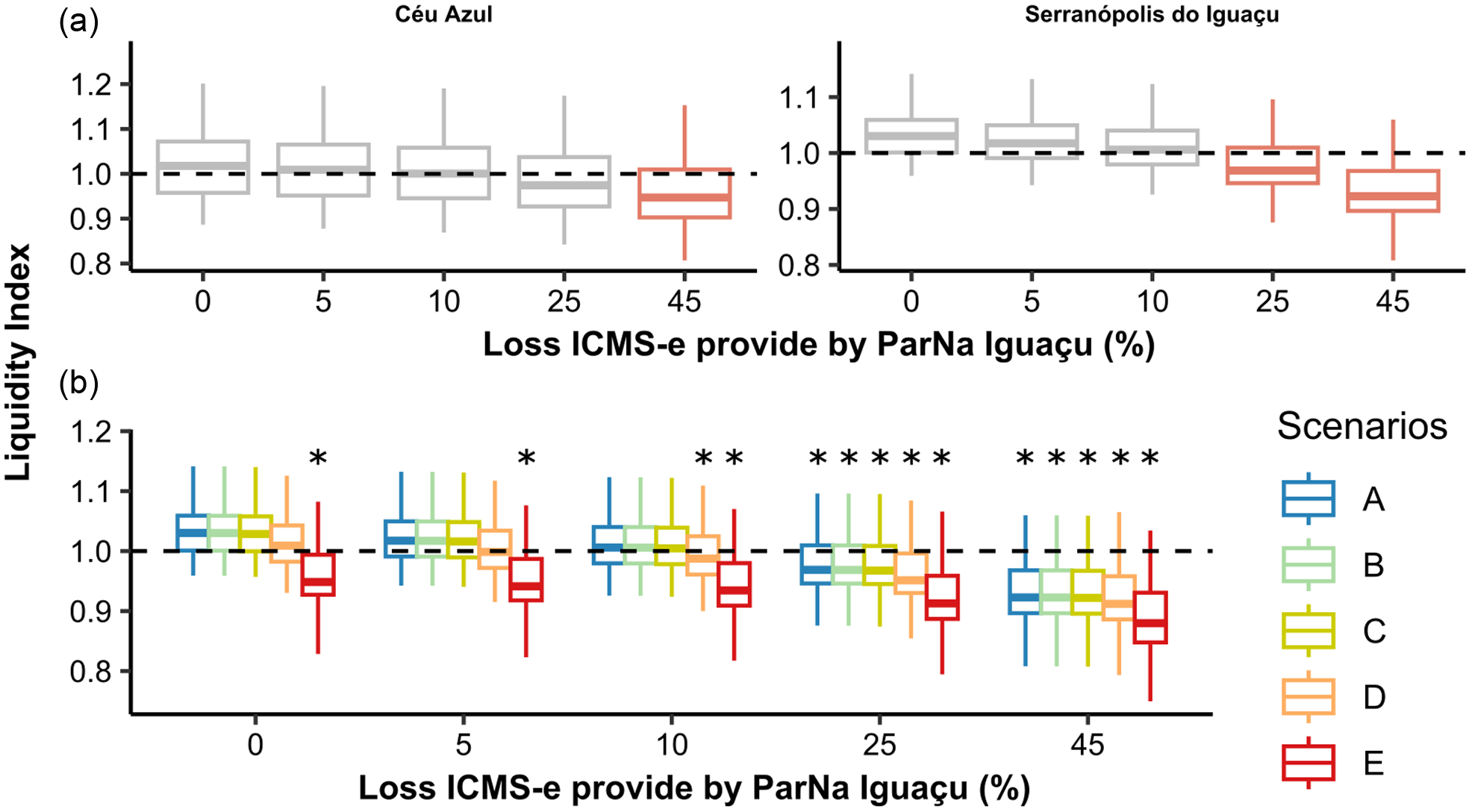

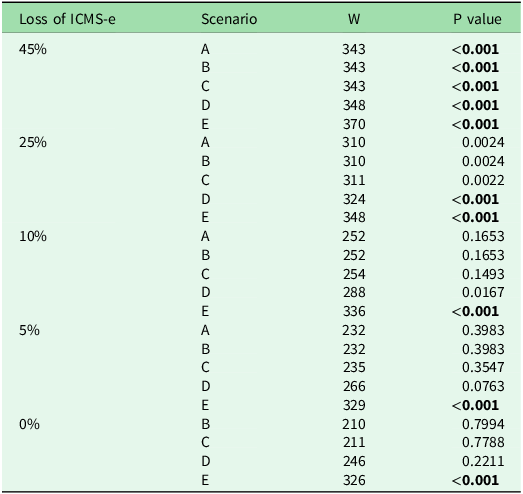

Figure 3. Possible reduction in ecological Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (ICMS-e) and its impact on the Liquidity Index due to the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road. (a) Percentage reduction in ICMS-e due to reduction in the conservation quality scores of ParNa Iguaçu, which can reach a maximum loss of 45% (boxplots in grey represents the percentages that did not show significant differences from the Liquidity Index). (b) Percentage reduction of ICMS-e in the municipality of Serranópolis do Iguaçu due to a reduction in the conservation quality scores of ParNa Iguaçu added to a reduction in the area of ParNa Iguaçu used in the calculation of ICMS-e in the following scenarios: A = no loss in the calculation area; B = loss of the area of the Caminho-do-Colono road; C = loss of the road area plus a 100-m buffer; D = loss of the road area plus a buffer of 1.5 km of edge effect on plant biomass (Chaplin-Kramer et al. Reference Chaplin-Kramer, Ramler, Sharp, Haddad, Gerber and West2015); and E = loss of the road area plus the area where illegal activities are likely to increase (Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Bertrand, Martello, Brocardo and Cunha2022). Asterisk (*) symbols indicate scenarios that had a Liquidity Index significantly lower than 1.

Economic performance of municipalities before and after the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road

None of the municipalities overlapping or neighbouring ParNa Iguaçu showed a higher LI while the Caminho-do-Colono road was open, and after the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road the municipalities of Foz do Iguaçu (W = 125, p = 0.008), Matelândia (W = 142, p = 0.025), Medianeira (W = 136, p = 0.017) and Vera Cruz do Oeste (W = 67, p < 0.001; Fig. 2b & Table 1) experienced surpluses in their public accounts. When considering the entire region composed of the 13 municipalities overlapping or neighbouring the National Park (sum of the region’s revenues divided by the sum of the region’s expenses), the period after the closure of the Caminho-do-Colono road showed a surplus compared to the period when the road was open (W = 137, p = 0.018; Fig. 2b & Table 1).

Impacts of reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road on the economic performance of the municipalities

If the quality score of the CU is impacted by the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road, a 25% reduction in transfer would affect the LI of Serranópolis do Iguaçu municipality (W = 310, p = 0.002), and a 45% reduction would negatively impact the LI of Céu Azul municipality (W = 287, p = 0.018; Fig. 3a & Table 2). Additionally, if the satisfactory area for ICMS-e calculation is altered due to the Caminho-do-Colono road reopening in Serranópolis do Iguaçu municipality, only the reduction in scenario E (outlined above; –10 025.6 ha) would have a significant impact on the LI, reducing it from 1.03 to 0.95 (W = 326, p < 0.001; Fig. 3b & Table 3). This worsens when combined with the 45% reduction – for example, potentially reducing the LI from 1.03 to 0.88 (W = 370, p < 0.001; Fig. 3b & Table 3).

Table 2. Wilcoxon test results for scenarios with percentage loss of ecological Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (ICMS-e) due to reductions in the conservation quality score of ParNa Iguaçu with the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road. Values in bold indicate statistically significant values.

Table 3. Wilcoxon test results for scenarios with percentage loss of ecological Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços (ICMS-e) and reduction of the satisfactory area in the calculation of ICMS-e due to the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road. Values in bold indicate statistically significant values.

Discussion

The National Park ensures the maintenance and persistence of forest cover within its territory over time, while native forests in the surrounding areas continue to diminish, ensuring the continuity of ecosystem processes and services that are not generated to the same extent in deforested areas. Locally, the maintenance of natural forests and water sources is rewarded through financial transfers by state governments, especially by Paraná, the pioneering state in implementing ICMS-e. Loss of this compensation could negatively affect the financial health of these municipalities. Although the values of ICMS-e do not affect the LI of the region as a whole, possibly because larger municipalities with diversified revenues do not depend on these values, smaller municipalities rely on this resource to maintain their financial balance. This demonstrates the importance of the National Park not only for biodiversity and ecosystem services, but also – although little recognized – for local economies.

Reduction of the remaining forest to the few small fragments in the landscape surrounding ParNa Iguaçu is a result of the historical and cultural context of land occupation from 1900 to 1990, which expanded from the coast to the western part of the state of Paraná in the so-called ‘march to the west’ (Gubert-Filho Reference Gubert-Filho2010). This colonization expansion reached the western part of the state c. 1920, and many families descended from European immigrants – mainly from the states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul – settled in the ParNa Iguaçu region, subsidized by the colonization companies and real estate agencies of the time, many of which were also logging companies. The suppression of native forests occurred primarily due to the expansion of the timber trade, mainly of araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia) and peroba (Aspidosperma polyneuron), and, subsequently, the progressive conversion, mainly in the 1950s, of these areas into small-scale agriculture and large areas of pasture, a transformation that continued until the mid-1990s (Priori et al. Reference Priori, Pomari, Amâncio and Ipoólito2012). Finally, in the last 20 years, these pastures have been converted to soybean and corn monocultures (MAPBIOMAS 2022). The creation of ParNa Iguaçu in 1939 allowed for the maintenance of native forest cover, protecting it from extractive territorial expansion throughout this period, marking the contrast observed in land cover around the National Park. This reinforces the effectiveness of establishing CUs (especially full-protection CUs) as a strong public policy for environmental conservation and preservation (Brocardo et al. Reference Brocardo, Szinwelski, Cândido Júnior, Squinzani, Prasniewski, Limont and Fadini2022).

Anthropogenic disturbances can cause a reduction in carbon stocks in forests, mainly through reduction and fragmentation, which lead to increased forest edges and allow for greater wind action, higher temperatures and lower humidity. These factors lead to increased plant mortality rates (Laurance & Curran Reference Laurance and Curran2008), resulting in a reduction in carbon stocks (Chaplin-Kramer et al. Reference Chaplin-Kramer, Ramler, Sharp, Haddad, Gerber and West2015). Thus, the deforestation and environmental degradation that would be caused by the reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road would directly affect the carbon stock in an area of 26.5 ha (17.5 km × 12.0 m). Indirectly, this impact would be much greater due to edge effects (Chaplin-Kramer et al. Reference Chaplin-Kramer, Ramler, Sharp, Haddad, Gerber and West2015). The reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road has the potential to compromise the ability of ParNa Iguaçu to maintain viable populations of various species, increasing the frequency of illegal activities such as hunting, fishing and extraction of palm hearts (Euterpe edulis) in an area of up to 10 000 ha (Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Bertrand, Martello, Brocardo and Cunha2022). Additionally, a road poses a severe risk of collisions for species such as the jaguar (Panthera onca; Brocardo et al. Reference Brocardo, da Silva, Feraciolli, Cândido Junior, Bianconi and Moraes2019), similarly to what has happened in Morro do Diabo State Park, where, in less than 1 week, two individuals of this species were run over on the highway that cuts through the State Park (G1 2023).

The environmental degradation that could be caused by reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road would also have direct impacts on the economies of municipalities overlapping or neighbouring ParNa Iguaçu because for some municipalities the ICMS-e values received for the conservation of forest environments have significant economic importance. Our results show that the collected ICMS-e represents a significant contribution to the revenue of the municipalities of Céu Azul and Serranópolis do Iguaçu, allowing for a surplus in these municipalities. Losses due to the Caminho-do-Colono road would be expected because the percentage that each municipality receives in ICMS-e transfer is based on how much it protects and conserves the National Park. The municipalities of Serranópolis do Iguaçu and Céu Azul would have their economic balance affected if there were a reduction in the transfer of this resource by 25% and 45%, respectively, solely due to the reduction in environmental quality scores. The municipality of Serranópolis do Iguaçu is the most dependent on ICMS-e from ParNa Iguaçu because the Caminho-do-Colono route is within its territorial limits; the reopening of this road could result in a financial deficit of up to 12% per year.

Contrary to what is argued by supporters of reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road, the financial balances of the municipalities, especially Capanema and Serranópolis do Iguaçu, were not higher when the road was in operation. Far from it – some municipalities showed a surplus in the period when the road remained closed, such as Matelândia and Medianeira (from which Serranópolis do Iguaçu was emancipated in 1997). This demonstrates, for example, that these municipalities, even though they are on the route of the Caminho-do-Colono road, developed without needing this environmental setback, a result that was also found when analysing the economy of all municipalities together. Regional factors that undoubtedly influenced this development include increased agricultural production, industrialization and tertiary services; relevant national factors include increased economic development after the mid-2000s (Reolon Reference Reolon2007). The economic dependence on this road is therefore a fallacious argument (Kropf & Eleutério Reference Kropf and Eleuterio2015), with municipalities satisfactorily overcoming the absence of this route.

Reopening the Caminho-do-Colono road would shorten (for a few) the distance between the municipalities of Serranópolis do Iguaçu and Capanema, although this shortcut would not serve to shorten the transport route for major agricultural products, such as soybeans. The reopening of the road would intensify various environmental problems that impact the collective and the revenues of the municipalities. Furthermore, the reopening of this road would deprive the National Park of its role in maintaining native vegetation in the western and south-western portions of Paraná, where human occupation has left a significant trail of environmental degradation. Finally, the present study demonstrates the possible negative financial impacts on nearby municipalities if this road were to be opened, and it dismantles the argument that the region would prosper with this road, an argument that is not supported by history.

The fallacious nature of political discourse claiming that Bills 7123/2010 and 984/2019, which propose reopening of the Caminho-do-Colono road, are needed for the economies of municipalities near the National Park is contradicted both by the expected losses of revenue to these municipalities from ICMS-e and by the fact that the economic performance of these municipalities was not negatively affected by the closure of the road in 2001. These results add to other studies that demonstrate the environmental setbacks that would occur with the implementation of these proposals (Ortiz Reference Ortiz2009, Prasniewski et al. Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Sobral-Souza, Kuczach, Brocardo, Sperber and Fearnside2020, Reference Prasniewski, Szinwelski, Bertrand, Martello, Brocardo and Cunha2022). The Caminho-do-Colono road is being used by politicians as an opportunity to exploit personal sentiments to obtain votes and to favour small groups to the detriment to the collective interest. Therefore, future studies and efforts should focus primarily on the sustainable use of the areas neighbouring ParNa Iguaçu. It is essential to document the benefits that municipalities can obtain from the expansion of protected areas, both in revenue and in ecosystem services associated with these natural regions. Instead of reducing or degrading the remaining natural vegetation, we should expand public policies – such as ICMS-e – that encourage the creation of natural areas. This would strengthen local and regional efforts to achieve global goals, such as Target 3 of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which aims to conserve 30% of terrestrial and marine habitat by 2030.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892924000201.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at ICMBio (Iguaçu National Park) and other scientists who contributed information to our manuscript or read and made suggestions on the text.

Financial support

VMP thanks CNPq for the doctoral scholarship (Process 141645/2020-2). NS was supported by the Araucária Foundation (nº 09/2021). PMF’s research is funded by the São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (FAPESP) 2020/08916-8, the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (FAPEAM) 0102016301000289/2021-33, FINEP/Rede CLIMA 01.13.0353-00 and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Processes 31103/2015-4, 406941/2022-0 and 312450/2021-4). TS-S is supported by FAPEMAT (FAPEMAT-PRO.000274/2023) and IABS/CECAV (call 01/2023 – TCCE Vale ICMBio/Cecav).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Our study does not involve humans or animals and is in accordance with national, local and institutional laws and requirements.