Between late August 2019 and March 2020, I was in Sierra Leone, my country of origin in West Africa, as a Fulbright US Scholar doing archival research for my second book provisionally titled “From ‘Whiteman’s Grave’ to Ebola: Sierra Leone’s History of Epidemics, 1787–2015.” The seven months I spent at the Sierra Leone Public Archives (SLPA) located on the campus of the University of Sierra Leone (Fourah Bay College) in Freetown, the coastal capital city, were part of a scheduled ten-month long trip that should have lasted until the end of June 2020. My stay in Freetown was cut short, however, due to the new coronavirus pandemic (and its deadly COVID-19 respiratory illness), which originated in Wuhan, China, late in 2019.Footnote 1 Indeed, the pandemic spread across the globe and upended normal life worldwide as government-imposed international travel restrictions increased, airlines reduced or stopped flights, and lockdowns took effect in several countries.Footnote 2 Therefore, even though I had been scheduled to be in Sierra Leone until the end of June, the Fulbright Office terminated its programs worldwide by mid-March, instructing all American Fulbrighters to travel back to the United States as soon as possible. For this reason, it was imperative for me to decide whether to leave Freetown or stay there until June, a decision with far-reaching implications for both my research and well-being amidst the pandemic. What did the uncertain turn of events mean for continuing to conduct archival research in Sierra Leone? Was the country prepared for the pandemic considering that the 2013–2015 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) epidemic had registered a heavy death toll and exposed Sierra Leone’s fragile health system and weakening economy?Footnote 3 And how well would its inhabitants cope with COVID-19 given the country’s limited financial resources and reliance on international intervention during health crises? These questions were going through my mind as the coronavirus outbreak spread around the world in the first quarter of 2020.

This article reflects on research experience in Sierra Leone as the COVID-19 outbreak expanded globally during my archival investigation of epidemics in the country since 1787, when Freetown became a haven for freed Blacks repatriated from Britain, Nova Scotia, and Jamaica.Footnote 4 While bearing witness to the country’s early preparations in anticipation of the looming pandemic, I place them within Sierra Leone’s past encounters with viral eruptions, among them the 1915–1916 smallpox epidemic and 1918–1919 influenza pandemic.Footnote 5 And these historical precedents of disease outbreaks during the colonial period allow us to adopt a longue-durée approach to mull over both the Ebola epidemic and coronavirus pandemic.

As a British colony in the early twentieth century, Sierra Leone’s responses to epidemics or pandemics depended to a large degree on policies from London with all the constraints brought on by limited financial commitments, shortages of medical personnel, and the racist ideologies that underpinned colonial governance. Yet, while disease episodes during the early twentieth century had no direct correlation to present-day outbreaks of Ebola and COVID-19 in Sierra Leone, a historical perspective is pertinent to comprehending the country’s epidemiologic landscape over time. Against this backdrop, personal and social narratives are essential for contextualizing archival research, particularly considering the diverse accounts they enable for enriching knowledge production in African history.Footnote 6

As a point of departure, it makes sense to draw attention to the coronavirus pandemic vis-à-vis Africa and the origins of infectious disease eruptions, African governments’ incapacity to deal with them headlong, and structural issues that undermine caregiving during health emergencies. Importantly, since the pandemic has exposed weak health systems, short-staffed medical personnel, poor infrastructure, and inadequate financial resources for many countries around the world, it offers a lens through which we spot broader issues about disparities in public health and medical knowledge, sanitation and hygiene, as well as the intersections of health, poverty, and politics across both time and space.Footnote 7 While medical and related academic studies on COVID-19 and its impact on various countries continue to increase, the major hotspots of the pandemic in Asia, Europe, and the Americas have received more attention than Africa – perhaps with the exception of South Africa.Footnote 8 For countries such as Sierra Leone and many others on the continent, this may be in part because COVID-19 cases and mortalities have been far less than those reported in the areas mentioned above. Still, this trend in documenting the pandemic is counterintuitive in that the orthodoxy on the origins of infectious diseases typically points to Africa – or Asia – as the hotbed of pathogens, including malaria, HIV/AIDS, and Ebola.Footnote 9 Not surprisingly, the high death toll from COVID-19 recorded in Italy, France, Britain, the USA, Brazil and India, among others, prompted early speculation that African countries with more fragile health systems would record higher numbers of fatalities.Footnote 10 So far, however, this prediction has not materialized.Footnote 11 And while the trajectory of the pandemic’s fatalities might change for the worse in Africa at some point, the need for scholarly studies on how COVID-19 infections and mortalities are transpiring in overlooked countries such as Sierra Leone cannot be overstated.

The main thrust of the article’s argument is that while the Ebola epidemic had exposed Sierra Leone’s unpreparedness and incapacity to cope with extensive disease outbursts, the country faced the coronavirus pandemic aware that the preceding epidemic had been a costly learning experience in terms of fatalities and economic impact. Hence, despite its weak health system and inadequate financial resources, Sierra Leone appeared to be in a better position than it was in 2014 to plan early and respond promptly to the pandemic, at least to minimize its spread and fatalities.

The narrative opens with a brief consideration of what it meant to be doing archival research on Sierra Leone’s history of epidemics at a time when a pandemic threatened to upend life for a nation devastated by its earlier struggle with Ebola slightly over six years earlier. In this context, instances of disease eruptions during the colonial period, when the country was a British colony, allow us to ponder historical epidemiology, which brings together “biomedical evidence in a field of social, economic, and environmental historical forces, and [lays out a framework] to analyze change over both time and space.”Footnote 12 In effect, an appraisal of both biomedical and non-biomedical factors is germane to getting a wholesome picture of Sierra Leone’s disease landscape, both past and present.

The succeeding section then examines Sierra Leone’s initial preparations in expectation of COVID-19, ruminating lessons learned (or not) from the earlier Ebola epidemic. A lethargic reaction to the 2014 outbreak meant the government of ex-president Ernest Bai Koroma (2007–2018) only declared a state of public health emergency at the end of July, about three months after the first reported case of EVD in the country. In contrast, with the advantage of hindsight and the coronavirus pandemic looming, the administration of President Julius Maada Bio enacted an international travel ban by mid-March 2020, even as Sierra Leone was still one of few West African countries without any recorded incident of COVID-19. In truth, it was only on 30 March, a day after I returned to the US, that Sierra Leone reported its first case.Footnote 13 Arguably, the government’s decision to decree transnational travel restrictions early on spared the country the rapid spike in COVID-19 infections and fatalities, unlike what happened during the Ebola epidemic. At that time, Sierra Leone recorded 3,928 EVD-related deaths by 21 June 2015, just over a year after the country reported its first case.Footnote 14 So far, while the coronavirus pandemic continues to spread, Sierra Leone has recorded a total of 4,068 COVID-19 cases, 79 deaths, and 911 active cases, whereas 3,078 infected people have recovered since the country reported its first case.Footnote 15

Archival Research and Disease Eruptions in Sierra Leone during the Colonial Period

By early 2020, the peculiarity of doing archival research on the history of epidemics in Sierra Leone as a pandemic threatened to upend normal life worldwide did not escape my attention. In retrospect, nineteenth-century European visitors to West Africa as well as scholars studying its colonial history have revealed that Sierra Leone (and West Africa) gained notoriety in Europe as the “Whiteman’s Grave” due to the severe death toll among visiting Europeans from diseases such as malaria and yellow fever.Footnote 16 Thus, as the 1800s continued, quinine became a common prophylaxis of choice for preventing malaria among British soldiers, administrators, merchants and missionaries (and other Europeans) visiting or residing in West Africa and other tropical areas of the British Empire.Footnote 17 Gradually, with knowledge about tropical diseases expanding by the early twentieth century, British colonial authorities grew more confident about their medicalization project in Sierra Leone and other West African colonies, even as financial constraints and ill-conceived public health policies irked them.Footnote 18

Browsing through archived colonial documents on public health and diseases in Sierra Leone nudged me to reflect on how epidemics/pandemics had affected the residents of Freetown back then, just as the city’s inhabitants were now gearing up for the pending coronavirus pandemic. And this jogged my memory about the stringent containment measures adopted by the government of Sierra Leone during the Ebola epidemic, which were reminiscent of the British colonial administration’s responses to both the 1915–1916 smallpox epidemic and 1918–1919 influenza pandemic.Footnote 19 For all intents and purposes, though, the quarantines and lockdowns authorized in Sierra Leone during the colonial period, just as during the more recent Ebola epidemic, turned out to be less effective in containing the infections than government officials in both instances had anticipated (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Inside the Sierra Leone Public Archives, USL (Fourah Bay College) Campus. (Photo by author, 20 February 2020). (In color online and print version)

As with the Ebola outbreak, the 1915 smallpox epidemic originated in Guinea, at that time a French colony, and spread into the northern parts of Sierra Leone, before reaching Freetown in the west.Footnote 20 Karene District, sharing a frontier with Guinea, became an epicenter as the disease spread across its numerous chiefdoms. By imposing quarantine and travel restrictions in the district, the colonial administration only made matters worse for the inhabitants. Farmers struggled to cultivate and harvest food crops, especially rice, the staple diet, while traders and merchants hoarded foodstuff in order to inflate prices and increase their profits.Footnote 21 For most local residents, the smallpox epidemic not only caused hundreds of deaths, but also brought hunger and famine. Before the smallpox epidemic dissipated in 1916, it infected about 70 percent of the population in Karene District, where over two thousand died of the disease.Footnote 22

In the case of the influenza pandemic, it arrived in Sierra Leone via HMS Mantua, a British commercial liner converted into an armed merchant cruiser, which docked at the Freetown harbor on 15 August 1918.Footnote 23 Before the outbreak of World War I, Freetown – then a coaling station for ocean-going steamers – served vessels of not only the British, who administered the colony, but also those of other European trading nations, most notably the French and Portuguese, who frequented the coast of West Africa on their way to central and southern Africa. Nonetheless, during the war, as the late physician-anthropologist Paul Farmer (1959–2022) explains, “The Mantua was assigned to protect a small convoy of merchant vessels headed through the U-boat-infested waters between England and West Africa and return with gold [from Sierra Leone] to help finance a final push against Germany and its allies.”Footnote 24 It was in this situation that the vessel arrived in Freetown with some of its crew infected with influenza. Historian Alfred Crosby affirms that by the time the Mantua berthed “200 of her sailors [were] sick or just recovering from influenza.”Footnote 25 From the crew, the disease spread to the Royal Army Medical Corps, as well as local laborers of the Mabella Coaling Station, which was responsible for supplying coal to ships in the Freetown harbor.Footnote 26 With little to no effective curative care for local residents, Freetown had recorded about 790 deaths within three weeks of the influenza outbreak.Footnote 27 By October, the number of fatalities had risen to 1,000. In all, an estimated 70 percent of Freetown’s population of about 34,000 possibly contracted influenza. Notably, younger people between the ages of 15 and 35 were particularly susceptible to the disease.Footnote 28 Furthermore, even though most of the influenza cases and casualties were concentrated in Freetown and its vicinity, other parts of the interior experienced the pandemic as well.

In terms of fatalities vis-à-vis infection rates, the influenza pandemic took a heavier toll on Sierra Leoneans than the current COVID-19 pandemic has done so far. Indeed, the 1918 pandemic not only registered a heavy death toll but also destabilized normal life and the livelihoods of thousands of people, particularly those living in Freetown and its environs. And just like the Ebola epidemic, the influenza pandemic caused anxieties about a possible return to normal life and what the “new normal” would be like. Anyhow, even more illuminating is the colonial administration’s racial bias in public health priorities while dealing with infectious diseases, as historian Festus Cole observes: “While the logic of colonial medicine aimed to protect the health of Europeans, there were problems in store for an administration whose apparent short-sightedness ignored the welfare of its subjects in its antimalarial campaigns.”Footnote 29 This tendency among British officials in colonial health policies, more often than not, undermined efforts to deal with public health issues effectively for all inhabitants of the colony regardless of “race”/skin color and/or ethnic origin.

Looking back, public health inequities among different groups of people – Europeans and Africans, rich and poor – indicate that Sierra Leone’s past encounters with disease eruptions, for better or worse, share an uncanny affinity with the country’s present-day struggles with epidemics/pandemics. Yet, as COVID-19 continued to spread, it remained to be seen if earlier widespread disease episodes had provided enough impetus for Sierra Leone to prioritize a robust public health system capable of providing prompt medical care at an affordable cost for those most in need.

Sierra Leone’s Response to COVID-19

About a month before I returned to the US at the end of March 2020, while continuing research at the Sierra Leone Public Archives (on the University of Sierra Leone campus), I noticed that buckets (“Veronica buckets”) of water, soap, and hand sanitizers were almost ubiquitous at the entrances of most buildings – the archival building, administrative offices, classrooms, laboratories, and library. Just as during the earlier Ebola outbreak, this effort was in response to a government directive imploring offices, schools, hotels, bars and restaurants, churches, mosques, and other public establishments to make water, soap, and hand sanitizers available and encourage handwashing even before the first case of COVID-19 appeared in the country.Footnote 30 In spite of the effort to sensitize people in Freetown – and the rest of the country – about the importance of handwashing to minimize the spread of COVID-19 in case it entered Sierra Leone, however, not everyone embraced it as a preventive measure, even at the university. In the same way, wearing masks and face coverings had yet to gain currency among most people in the city. Yet, knowing what Sierra Leone had gone through during the Ebola epidemic, there was good reason to be apprehensive about the potential loss of lives COVID-19 could cause in the country. This was particularly worrisome as practicing social distancing was unmanageable in Freetown, an overcrowded city with densely inhabited public spaces, particularly marketplaces that were busy throughout the week, besides its sprawling slums in the central and eastern parts of the city.

Even before Sierra Leone reported its first case of COVID-19, the government and both news and social media had started informing the public about the threat posed to public health by a potential spread of the coronavirus pandemic in the country.Footnote 31 Indeed, for most Sierra Leoneans, this evoked grim reminders about the Ebola outbreak, when about 4,000 people lost their lives in the country. Still, as during the preceding epidemic, reports about the spread of COVID-19 in other parts of the world bred local rumors and speculation that captured public imagination.Footnote 32 Misinformation about COVID-19 made it difficult to convince people to take the awareness campaigns about the looming pandemic seriously. But as other African countries reported increasing cases of COVID-19, people in Freetown and the rest of the country began to contemplate with more seriousness the possibility of the pandemic spreading into the country.

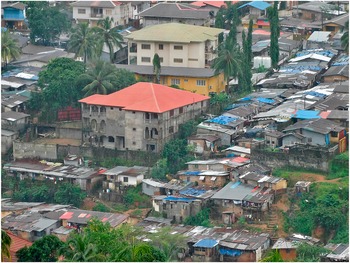

From February and early March 2020 onward, it was noticeable that the government of Sierra Leone had started to prepare in earnest to cope with the spread of COVID-19 into the country. Among the measures taken in Freetown and its neighborhoods, as mentioned earlier, the most common was placing soap and water and hand sanitizers for public use at the entrance of government buildings, institutions of learning, places of worship, hotels and restaurants, and similar spaces. The Ministry of Health and Sanitation launched an awareness-raising or sensitization campaign urging members of the public to practice basic hygiene, including frequent handwashing, and avoid huge public gatherings.Footnote 33 Aware that practicing social distancing would pose a serious challenge for the overcrowded Freetown area, the government stressed the importance of minimizing personal contact, including handshaking and hugging, rather than impose strict social-distancing rules (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lumley Neighborhood in the West End of Freetown, Sierra Leone. (Photo by author, 5 September 2019). (In color online and print version)

Throughout the earliest efforts to prepare for COVID-19 in Sierra Leone, the Freetown City Council (FCC), which has jurisdiction over the capital city and its vicinities, played a leading role. The FCC collaborated with the national government to map out its preparedness strategies and COVID-19 response plan by identifying Freetown’s specific challenges and extracting lessons learned from the earlier Ebola response to inform its preparation.Footnote 34 Moreover, the FCC borrowed successful containment strategies from South Korea and Singapore, including extensive testing, quick detection and diagnosis, social distancing, strict quarantine and government transparency, as a template to emulate.Footnote 35 As the Mayor of Freetown Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr explained,

The plan had three key elements responding to the fact that this is a city where 35 percent of our populace live in informal settlements which are densely crowded with very little space for social distancing…. Another very important feature is the fact that 47 percent of the population do not have access to running water. Given that the other most significant element of protection is hand-washing, our plan needed to reflect these particularities.Footnote 36

To be sure, the FCC was pragmatic enough to realize that Freetown’s densely populated communities, overcrowded markets and other public spaces, and unreliable water supply could make handwashing and social distancing extremely difficult for people to follow as preventive measures. Another problem the FCC recognized was the fact that most people in Freetown – and the rest of the country – lacked money to buy food in bulk and store at home, a situation that could make lockdowns difficult to enforce.

Against this backdrop, on 24 March 2020, President Bio declared a state of public health emergency expected to last for twelve months. In a televised broadcast, he presented the rationale behind the declaration: “The rapid global spread of the coronavirus poses an immense risk to human beings that can lead to major loss of life and can cause socioeconomic disruption in Sierra Leone…. This situation requires effective measures to prevent, protect, and curtail the spread of the coronavirus disease in Sierra Leone.”Footnote 37 President Bio emphasized that the emergency was not a national lockdown. Therefore, he warned, those involved in commercial activities had no excuse for hoarding goods and/or hiking prices.

Importantly, as in the case of the Ebola epidemic, both the military and police were authorized to enforce compliance with the public health ordinances, among them curfews (when imposed), travel restrictions, and limitations on public gatherings. To be sure, the emergency declaration triggered public criticism, not least because many Sierra Leoneans inferred a political motive behind the president’s declaration that the emergency would last for a year.Footnote 38 And even as he did not immediately enact a national lockdown with the emergency, it brought back memories of what had transpired during the Ebola epidemic, when lockdowns and mass quarantines did more harm than good, especially for people living in poverty both in urban centers and rural areas.Footnote 39

After Sierra Leone reported its first COVID-19 case at the end of March, the government announced a three-day lockdown from 5 April to 7 April. Then, on 14 April, it limited inter-district travel and put into action a nationwide curfew lasting from 11:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m.Footnote 40 In Freetown, as in other parts of the country, any strict lockdowns would only make matters worse for the vast majority of people whose livelihood depended on daily activities away from their homes. Food handouts, when provided by charitable organizations, including Non-Governmental Agencies (NGOs), churches, and mosques, were most times insufficient to meet the needs of the poor. And those who violated the curfew in order to search for food for their families or attend to any other pressing needs risked police or military brutality. Still, corrupt police and military officers solicited bribes from curfew violators in exchange for “free passage” without any penalty.Footnote 41 Undoubtedly, these factors undermined public trust in law enforcement officials and the government, making compliance with the emergency orders more difficult.

Realizing that implementing the emergency with a strict curfew and travel restraints that did not reflect the number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the country could arouse a public uproar, the government decided to lift some restrictions on 24 June. During the same month, though, health workers involved in the COVID-19 response went on strike, citing non-payment of their hazard allowances as the main reason. Likewise, in July, doctors resorted to strike action over their hazard allowances as well as the unavailability of protective equipment for them to treat COVID-19 patients.Footnote 42

All told, despite Sierra Leone’s historical encounters with widespread disease outbreaks, preparing for the coronavirus pandemic presented its fair share of challenges. And although the earlier Ebola epidemic had highlighted the importance of a wholesome health system, including well-trained and paid health workers, early preparedness, and proactive responses, the current government still found itself challenged by recurrent problems that had been the bane of the country’s post-civil war existence – frail economy, poor infrastructure, overreliance on international intervention, and public distrust in government. Significantly, however, up to the time of writing Sierra Leone’s experience with COVID-19 had not revealed anything near the kind of devastating death toll it had suffered during the Ebola epidemic of 2014.

As far as the bigger picture of my ongoing research on the history of epidemics in Sierra Leone is concerned, the assumptions that informed Western media reporting as COVID-19 spread into Africa (and elsewhere in the developing world) brought to mind the reductionist slant of European colonial discourses and tropes about Africa and its peoples. Depicting Sierra Leone (and the rest of West Africa, by extension) as the “Whiteman’s grave” was just one aspect of the inclination toward downgrading tropical colonies to “diseased environments” in spite of British exploitation of natural resources in the same colonies. In truth, “tropical medicine” as a field of scholarship emerged during the second half of the nineteenth century to constitute a crucial part of the British Empire’s agenda to study diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, and trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), among others. This, the British envisioned, would make such colonies healthier and more habitable, especially for European colonial administrators, military personnel, missionaries, and merchants/traders. In the case of Sierra Leone more specifically, the founding of the Sir Alfred Jones Laboratory in Freetown in 1922 marked the culmination of a shift from dispatching British research expeditions to West Africa in the late 1800s to having a permanent station in one of the colonies for research on tropical diseases to be conducted.Footnote 43 While such projects represented a genuine effort to learn about uncommon diseases in Europe, they also embodied the presumed cultural superiority and racist baggage that underpinned British colonialism in Sierra Leone and elsewhere in Africa. All told, the structural inequities revealed by the current COVID-19 pandemic represents a continuum in preconceived attitudes, perceptions, and shortcomings in public health that have historical precedents that are not as remote as one might be tempted to think.

Conclusion

This article aimed to provide a narrative about research experience while doing archival investigation in Sierra Leone on its history of epidemics as the coronavirus outbreak spread across the world from early 2020 onward. In so doing, I made the case that Sierra Leone’s previous experience with the Ebola epidemic put the country in a better position to prepare early and respond promptly to the current pandemic. Despite its poor health system and inadequate financial resources, by mid-March the government of Sierra Leone had enacted an international travel ban aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19 in the country. Within this context, conducting archival research in Freetown on historical epidemiology in the country provided a unique opportunity to witness the initial preparations as everyone geared up for the somehow unavoidable encounter with the coronavirus pandemic.

Notwithstanding its apparent vulnerability, however, Sierra Leone did not record its first case of COVID-19 until the end of March 2020. And up to the time of drafting this article, the country was still among a narrow list of countries with a small number of COVID-19 fatalities – below 100. At the same time, considering Sierra Leone’s historical encounters with epidemics/pandemics, Farmer’s position about the need for a more efficient public-health approach demands attention: “Until the insidious control-over-care paradigm is broken, the response to those epidemics [such as Ebola, malaria, and cholera] will be continued mistrust and recalcitrance on the part of populations already scarred by insults and injuries of colonialism, war, and a public-health approach that fails to prioritize effective caregiving.”Footnote 44

Although it is too early to assess the death toll and economic impact of the pandemic on Sierra Leone, it might not be farfetched, based on evidence so far, to speculate that the country’s casualties from COVID-19 will be nowhere near the almost 4,000 victims the Ebola epidemic claimed. If the country maintains a grip on its current COVID-19 infection rate through effective contact-tracing and hospitalization of infected people, it seems reasonable to suggest that Sierra Leone would have done a better job of containing the pandemic than it did with the Ebola outbreak. Moreover, with access to vaccines against COVID-19, the country could spare its people another disastrous encounter with a deadly infectious virus that has already claimed millions of lives around the world. And with my archival research for a monograph on the history of epidemics in Sierra Leone still a work in progress, this narrative will have a sequel featuring the complex nature of interactions between diseases, peoples, and environments as evidenced by the snippets of records presented here.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have turned on its head the penchant for portraying Africa as a hotbed of “exotic diseases” so common in Western media reports, which brings to mind European colonial discourse about the White Man’s grave.Footnote 45 Sure enough, the virulent virus embodied a paradox insofar as countries with industrial economies registered more deaths than poorer African countries, even as global structural inequities and fragile infrastructure across the continent still hamper the delivery of proper healthcare in the “clinical desert” of West Africa, to borrow from Farmer.Footnote 46 In truth, Africa’s postcolonial era has exposed poor economic planning and financial mismanagement, political instability, and dwindling natural resources that have compounded poverty in many countries like Sierra Leone. Not surprisingly, millions of Africans remain susceptible to endemic diseases ranging from malaria to cholera and HIV/AIDS. In addition, emerging diseases, among them COVID-19, have only increased the threat posed by epidemics/pandemics, which typically require transnational and international cooperation to alleviate the suffering of the poor and most vulnerable during health crises. Significantly, therefore, without a concerted effort at a global level to address the structural impediments to basic healthcare provision across nations, the chances of combatting epidemics/pandemics successfully as they spread will remain uncertain not only in countries such as Sierra Leone but also in China, the USA, Italy, India, and Brazil, among others.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to the following sponsors for funding research in Sierra Leone for a larger book project still in progress that initiated this article: The Fulbright US Scholars Program and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

The author is thankful to Mr. Alfred Fornah, Archivist/Records Manager at the Sierra Leone Public Archives in Freetown, whose familiarity with the documents housed there made it easier to locate them without delay.

The author appreciates the suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers who reviewed this article for History in Africa.