Bipolar disorder is a serious, chronic mental disorder characterised by recurrently alternating episodes of mania or hypomania and episodes of depressive mood.Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1 Manic state refers to abnormally heightened or irritable mood, elevated energy, impulsivity and other related symptoms lasting for 7 or more days, whereas hypomania is the presence of the same symptoms for 4 consecutive days.2 Depressive mood is characterised by low mood, low energy and sad, indifferent or hopeless periods. The mood shifts in bipolar disorder can be intense and disruptive, affecting a person's daily life, relationships and overall functioning.3

Bipolar disorder ranks among the top ten causes of disability in developed countries and has been identified as the fourth leading cause of neuropsychiatric disability in individuals aged 15–44 years, according to the World Health Organization.Reference López-Muñoz, Shen, D'Ocon, Romero and Álamo4 In the USA, approximately 4.4% of the overall population is affected by bipolar disorder, based on a 2015 estimate. Typically emerging in late adolescence or adulthood, this condition requires ongoing intervention and management; however, early detection remains challenging. On average, there is a 6- to 8-year gap between the onset of symptoms and an official diagnosis. Given the chronic nature of the symptoms throughout one's life, bipolar disorder constitutes a significant contribution to mental disorders in the USA.Reference Cerimele, Fortney and Unützer5

The treatment primarily includes pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions; however, challenges such as mood relapse and incomplete response, particularly in cases of depression, are prevalent.Reference Lin, Yang, Park, Jang, Zhu and Xiang6 Continuous reassessment and treatment modifications are often necessary for the ongoing, long-term care of individuals with bipolar disorder.Reference Jain and Mitra7

The medical approach to treating bipolar disorder has evolved from methods based on individual experience in the early 1990s to a more scientifically evidence-based approach in recent years. This evidence-based approach has had a pivotal role in the formulation of clinical practice guidelines and treatment algorithms for bipolar disorder.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8 However, the generation of scientific evidence and recommended treatments can vary depending on factors such as research infrastructure, health insurance policies, economic conditions and cultural distinctions in the country where the guidelines are established.Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1 This study aimed to delve into and compare several international guidelines for treating bipolar disorder, updated after 2014, including those from the UK, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, South Korea and the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP), to discern the factors contributing to the observed differences among them.

Method

The diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder outlined in the DSM-5, bipolar disorder subtypes and the therapeutic management of bipolar disorder were studied. Regarding the therapeutic management of bipolar disorder, we conducted an in-depth comparative analysis of multiple guidelines, with a focus on those revised within the past decade, specifically after 2014. This analysis included the Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Bipolar Disorder 2022 (KMAP-BP 2022),Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1 the 2016 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines for treatment of bipolar disorder (BAP 2016),Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9 the 2014 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Clinical Guideline for bipolar disorder (NICE 2014),2 the 2018 and 2021 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder (CANMAT 2018, 2021),Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Yatham, Chakrabarty, Bond, Schaffer, Beaulieu and Parikh11 the 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders (RANZCP 2020),Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12 and the 2017 CINP treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder (CINP-BD 2017).Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13 Our aim was to compare and analyse the variations with respect to major recommended drugs and the underlying reasons for these variations. The selection criteria primarily focused on guidelines revised within the past decade (after 2014), addressing the management of bipolar disorder in a general context. Consequently, we excluded a guideline on the treatment-resistant aspect of bipolar disorder that was published in 2020.Reference Fountoulakis, Yatham, Grunze, Vieta, Young and Blier14

Results

Diagnostic criteria

The DSM-5 serves as a standard reference for the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders, including bipolar disorder. It classifies bipolar disorder into categories, including bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, other specified bipolar and related disorders, and bipolar or related disorders, unspecified.Reference Jain and Mitra7

For a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, meeting the criteria for a manic episode (as provided below) is essential, which may occur independently or be accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes, although these episodes are not mandatory for the diagnosis:

(a) Fulfils criteria for at least one manic episode (Table 1);

(b) The presence of manic and major depressive episodes is not more effectively explained by other psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia.15

Table 1 Comparison of manic, hypomanic and depressive episodes

For a bipolar II disorder diagnosis, meeting criteria for at least one current or past hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode without a manic episode is required (Table 1):

(a) No manic episode has occurred;

(b) The hypomanic and major depressive episodes are not more effectively explained by other psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia;

(c) depression symptoms or the unpredictability resulting from frequent shifts between depression and hypomania cause clinically significant distress.15

Treatment and/or management

The key focus in treatment of bipolar disorder has traditionally been the effective management of manic, hypomanic or depressive episodes during clinical care, with a subsequent emphasis on preventing the recurrence of future episodes.Reference Goes16 The following section briefly outlines the medications predominantly recommended in the treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder.

Lithium has demonstrated effectiveness in treating acute episodes of both manic and depressive polarity, as well as in preventing the recurrence of episodes of either polarity.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12 Lithium is notably superior in preventing suicidal behaviour and mitigating suicide risk, demonstrating a substantial reduction in self-harm or suicidal behavior.Reference Shah, Grover and Rao17,Reference Benard, Vaiva, Masson and Geoffroy18

Valproate and its formulations are beneficial in treating bipolar disorder, demonstrating efficacy in managing acute mania and mixed episodes, although the existing evidence for its effectiveness in acute depression is more limited than that for lithium; it is also effective in preventing both mania and depression during the maintenance phase.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Crapanzano, Casolaro, Amendola and Damiani19

Lamotrigine has demonstrated effectiveness in treating bipolar depression and preventing the recurrence of depression, and its initial administration should involve a gradual dose escalation.Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9 However, it is crucial to note that a potentially severe side-effect is the development of skin rash, including conditions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis, necessitating thorough patient education.Reference Ng, Hallam, Lucas and Berk20

Typically, carbamazepine is employed when lithium treatment is ineffective or presents undesirable side-effects, and it has proved effective in both the management of acute bipolar mania and the prevention of relapse.Reference Chen and Lin21

Atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine, quetiapine, asenapine, risperidone and ziprasidone are effective in treating acute mania. In addition, quetiapine monotherapy and the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine are supported by evidence for managing depression.Reference Rybakowski22 Both olanzapine and quetiapine, whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively with lithium or valproate, have proved effective in preventing relapses of both depression and mania.Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and lorazepam, studied alongside lithium in bipolar disorder treatment, pose challenges in differentiating antimanic properties from sedative effects, leading to their categorisation as adjunctive options for acute episode management.Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9 Other medications, such as calcium channel blockers, zonisamide and omega-3 fatty acids, lack sufficient evidence as first-line treatments for bipolar mania and depression.Reference Benard, Vaiva, Masson and Geoffroy18

The use of antidepressants in bipolar depression is controversial owing to the risk of manic or hypomanic switching. Combining antidepressants with mood stabilisers is deemed more effective without an increased risk of manic switching.Reference Gitlin23 Antidepressants may not be suitable for rapid cycling affective disorder or mixed episodes.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

Bipolar disorder guidelines across regions

Comparison of therapeutic guidelines for bipolar disorder

The Korean guidelines (KMAP-BP) were developed based on the expert consensus of Korean psychiatrists with expertise in bipolar disorder treatment, using the Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000 survey method. The questionnaire used a nine-point scale to assess the appropriateness of each detailed item.Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1 The British guidelines (BAP) comprised clinical guidelines and key point lists with evidence categorised from Category I (strongest) to Category IV (weakest), and recommendation strength classified from Grade High to Grade Very Low. Interpretation of BAP guidelines are recommended in conjunction with NICE guidelines.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

CANMAT guidelines were based on evidence ranging from level 1 (strongest) to level 4 (weakest) for safety, tolerability and risk, influencing treatment recommendations.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10 The CINP-BD guidelines were developed with the involvement of experts with extensive research and clinical experience, who graded treatment efficacy, safety and tolerability from level 1 to level 5 and presented recommendations in five stages.Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13 The NICE guidelines provided relatively simple recommendations without clear evidence intensity, whereas the RANZCP guidelines presented treatment stages as ‘action’, ‘choice’ and ‘alternative’, similar to other mood disorder guidelines and combining evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8

Korea (KMAP-BP 2022)

Treatment strategy for manic episodes

In formulating a first-line strategy for bipolar disorder with manic episodes, the consideration for euphoric mania involved prioritising mood stabilisers combined with atypical antipsychotics, mood stabiliser monotherapy or atypical antipsychotic monotherapy. For manic episodes accompanied by psychotic features, a preference emerged for a combination of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics, with atypical antipsychotic monotherapy being a major choice.

When opting for monotherapy for manic episodes, preferred drugs encompass lithium, valproate, quetiapine, olanzapine and aripiprazole. Notably, for manic episodes with psychotic features, prominent choices involve olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole and risperidone. In cases of combination therapy with lithium or valproate, quetiapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole and risperidone emerge as major choices for both euphoric mania and manic episodes with psychotic features. However, when combining lithium for manic episodes with psychotic features, priority is given to quetiapine and olanzapine. On the other hand, when combining valproate, quetiapine is recommended.

If there is an insufficient response to the first-line strategy, subsequent therapeutic interventions involve adding an atypical antipsychotic after mood stabiliser monotherapy for euphoric mania. In addition, a significant option is to add a mood stabiliser after atypical antipsychotic monotherapy. In cases where patients show no response in the presence of psychotic features, the primary strategy is to switch to another medication. Although there are no significant differences in strategies for bipolar disorder with psychotic features, preferences vary depending on whether the patient is non-responsive or partially responsive.

For cases where combination therapy with mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics shows insufficient response, recommendations include switching to or combining existing medications such as lithium, valproate, quetiapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole and risperidone.Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

Treatment strategy for depressive episodes

The primary strategy for mild to moderate depressive episodes, as outlined in Table 3, remains consistent. Regarding specific preferred medications, for severe depressive episodes without accompanying psychotic features, first-line mood stabilisers for both monotherapy and combination therapy include lithium, lamotrigine and valproate, and the first-line atypical antipsychotics are aripiprazole, quetiapine and olanzapine.

In the case of depressive episodes accompanied by psychotic features, similarly, the first-line mood stabilisers for both monotherapy and combination therapy are lithium, lamotrigine and valproate. The first-line atypical antipsychotics in this context are again aripiprazole, quetiapine and olanzapine. For combination therapy, specifically addressing depressive episodes with psychotic features, the first-line atypical antipsychotics are aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine and risperidone. Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

Treatment strategy for mixed features

KMAP 2022 categorised mixed features into the following divisions: mixed manic episodes, mixed depressive episodes and mixed features without predominant symptoms (Table 2). For mixed manic episodes, the prioritised treatment was a combination therapy of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics, with atypical antipsychotic or mood stabiliser monotherapy being the first-line strategy. Preferred treatment medications included valproate, lithium, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone.

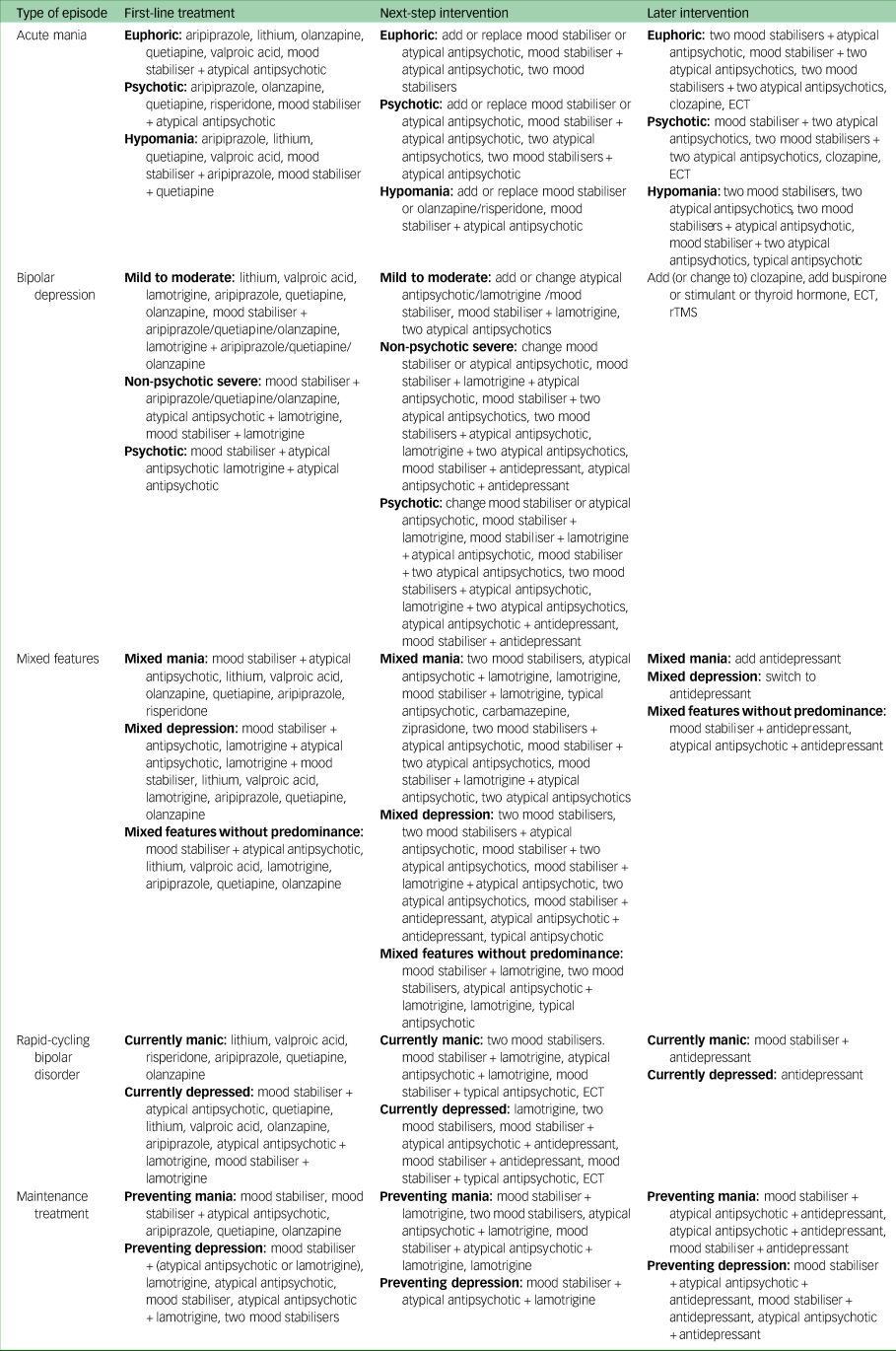

Table 2 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to KMAP-BP 2022

Atypical antipsychotics include olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole and risperidone. ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; KMAP-BP, Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Bipolar disorder; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

In the case of mixed depressive episodes, the primary strategies involved a combination of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics, a combination of atypical antipsychotics and lamotrigine, atypical antipsychotic monotherapy, combinations of mood stabilisers and lamotrigine, and mood stabiliser monotherapy. The preferred treatment medications were lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, aripiprazole, olanzapine and quetiapine.

For mixed features without predominant symptoms, the first-line strategies included combinations of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics, and atypical antipsychotic or mood stabiliser monotherapy. The preferred treatment medications were lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, olanzapine and quetiapine (Table 2).Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

Treatment strategy for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder

In patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder experiencing manic episodes, primary strategies included a combination of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics, mood stabiliser monotherapy and atypical antipsychotic monotherapy. The same first-line approaches were recommended for those with rapid-cycling bipolar depression; in addition, combinations of atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilisers with lamotrigine were selected as first-line strategies. Subsequent therapeutic interventions for patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder with manic symptoms involved options such as combinations of two mood stabilisers, combinations of mood stabilisers and lamotrigine, combinations of atypical antipsychotics and lamotrigine and combinations of mood stabilisers and typical antipsychotics.

For patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder not responding adequately to mood stabiliser monotherapy, the expert committee prioritised the addition of an atypical antipsychotic as the first-line treatment strategy, with the addition of another mood stabiliser also considered as a primary intervention. Subsequent interventions included switching to another mood stabiliser, adding lamotrigine, adding typical antipsychotics and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (Table 2).Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

Maintenance treatment strategy

The post-manic maintenance treatment strategy, as outlined in Table 2, prioritises monotherapy with a mood stabiliser, monotherapy with an atypical antipsychotic, and combinations of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics as first-line approaches. Subsequent interventions involve combinations such as mood stabilisers or atypical antipsychotics with lamotrigine; combinations of two mood stabiliser; combinations of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics with lamotrigine; lamotrigine monotherapy; combinations of mood stabilisers with atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants; and combinations of atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilisers with antidepressants.

For maintenance treatment after depressive episodes, primary strategies include combinations of mood stabilisers with atypical antipsychotics or lamotrigine; lamotrigine monotherapy; monotherapy with an atypical antipsychotic; monotherapy with a mood stabiliser; combinations of mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics with lamotrigine; and combinations of two mood stabilisers. The preferred antidepressant choices for maintenance treatment are bupropion as the first-line option, followed by escitalopram and sertraline (Table 2).Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

UK (BAP 2016, NICE 2014)

Treatment strategy for manic episodes

The first-line treatment recommendations for non-adherent patients with bipolar disorder, as per the NICE 2014 and BAP 2016 guidelines, include haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine as first-line atypical antipsychotics. For patients already on long-term medication, the initial step involves optimising and enhancing the current regimen, with the possibility of adding haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone or quetiapine during this process (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to BAP 2016

BAP, British Association for Psychopharmacology; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy.

Table 4 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to NICE 2014

adj, adjuvant; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

In the second stage, whereas NICE 2014 suggests transitioning to alternative antipsychotics or adding lithium or valproate, BAP 2016 recommends aripiprazole, carbamazepine, lithium and a combination of mood stabilisers with atypical antipsychotics (Table 4).2,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Treatment strategy for depressive episodes

In the first stage, the use of quetiapine, olanzapine and lurasidone as monotherapy was initially recommended by BAP 2016. The NICE 2014 guidelines, on the other hand, recommend the olanzapine–fluoxetine complex (OFC), quetiapine, olanzapine and lamotrigine as initial options. In addition, adjunct strategies involving OFC, quetiapine, olanzapine or lamotrigine are recommended by NICE 2014.

In the second stage, BAP 2016 recommends adding antidepressants and ECT as subsequent therapeutic interventions. NICE 2014, on the other hand, suggests adding lamotrigine in later stages but does not provide recommendations for ECT (Tables 3 and 4).2,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Treatment strategy for mixed features

During the initial stage, BAP 2016 suggests considering haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine and valproate as the foremost treatment options. Emphasising a primary combination therapy, the guidelines recommend combining lithium with haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, valproate or aripiprazole. By contrast, in the NICE 2014 guidelines, the preferred first-line treatment consists of monotherapy with haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone. Furthermore, the primary combination therapy involves the administration of lithium with haloperidol (or olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone) (Tables 3 and 4).2,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Maintenance treatment strategy

In the first stage of treatment, both BAP 2016 and NICE 2014 guidelines concur in recommending lithium as the primary choice for maintenance therapy. In the second stage, BAP 2016 offers treatment recommendations based on symptom dominance. For cases where mania is predominant, the guidelines suggest valproate, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone long-acting injectable (RIS LAI), carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. In situations where depression takes prominence, the guidelines recommend lamotrigine, quetiapine and lurasidone. Furthermore, BAP 2016 advocates considering various approaches such as combination therapy, antidepressants, clozapine and maintenance ECT for later interventions. On the other hand, the NICE 2014 guidelines suggest valproate, olanzapine and quetiapine as secondary strategies (Tables 3 and 4).2,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Canada (CANMAT 2018, 2021)

Treatment strategy for manic/hypomanic episodes

In the initial stage, CANMAT 2018 recommends adjunctive primary treatment strategies for mania involving monotherapy with quetiapine, asenapine, paliperidone, risperidone or cariprazine. Alternatively, combining quetiapine, risperidone or asenapine with a mood stabiliser is suggested.

For the second-line strategy of CANMAT 2018, options include monotherapy with olanzapine, carbamazepine, ziprasidone or haloperidol. Moreover, combinations such as olanzapine with a mood stabiliser or the use of two mood stabilisers are considered. ECT is preferred as a second-line intervention. CANMAT 2018 also proposes subsequent strategies such as combining carbamazepine with a mood stabiliser, chlorpromazine, clonazepam, clozapine, combining haloperidol with a mood stabiliser, and non-pharmacological approaches such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), tamoxifen and combinations of mood stabilisers with tamoxifen.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10

Treatment strategy for depressive episodes

In the initial stage, primary treatment strategies include the option of monotherapy with quetiapine, lamotrigine or lurasidone. Furthermore, combining a mood stabiliser with lurasidone or using lamotrigine as an adjunctive therapy is recommended for managing bipolar depression.

In the second stage, CANMAT 2018 introduces additional strategies such as monotherapy with valproate, cariprazine or OFC. Alternatively, adjunctive selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or bupropion can be considered as part of the treatment plan.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10

Treatment strategy for mixed features

The CANMAT 2021 guidelines describe the first-line treatment medications for mixed features as ‘undecided’. Asenapine or aripiprazole may be considered as first-line treatments without one being superior to the other.

CANMAT 2021 proposes second-line treatment options for mixed mania, including asenapine, cariprazine, valproate and aripiprazole. For mixed depression, cariprazine and lurasidone are suggested, whereas for cases without predominant symptoms, combining olanzapine with a mood stabiliser or monotherapy with carbamazepine, olanzapine or valproate is recommended.Reference Yatham, Chakrabarty, Bond, Schaffer, Beaulieu and Parikh11

Maintenance treatment strategy

For maintenance treatment, CANMAT 2018 recommends lithium, quetiapine, valproate, lamotrigine, asenapine, aripiprazole and monthly aripiprazole as first-line strategies.

In the next stage of the CANMAT 2018 strategy, options include olanzapine, RIS LAI, carbamazepine, paliperidone with adjunctive RIS LAI or combination therapy with a mood stabiliser and lurasidone (or ziprasidone). The guidelines further recommend considering interventions such as combining aripiprazole with lamotrigine, OFC, adjunctive clozapine and adjunctive gabapentin for later stages of maintenance treatment (Table 5).Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10

Table 5 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to CANMAT 2018 and CANMAT 2021

adj, adjuvant; CANMAT, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; LAI, long-acting injectable; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SNRI, serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Oceania (RANZCP 2020)

Treatment strategy for manic/hypomanic episodes

In the context of patients with manic episodes, RANZCP 2020 identifies aripiprazole, asenapine, cariprazine, quetiapine, risperidone and valproate monotherapy as the primary choices for initial treatment. The guidelines also advocated for the primary strategy of either lithium monotherapy or the combination of a mood stabiliser with an atypical antipsychotic.

In the second stage, carbamazepine, ziprasidone, haloperidol and olanzapine are considered as secondary treatment options, whereas ECT was recommended as a tertiary intervention.Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

Treatment strategy for depressive episodes

In the initial stage, RANZCP 2020 recommends the use of lithium, lamotrigine, valproate, quetiapine, lurasidone and cariprazine as primary therapeutic options. In the most recent guideline, RANZCP 2020 proposed a second-stage intervention, as outlined in Table 6. This subsequent phase introduces therapeutic choices such as monotherapy with carbamazepine and olanzapine, along with adjunctive treatments involving asenapine, armodafinil and levothyroxine.Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

Table 6 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to RANZCP 2020

adj, adjuvant; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; RANZCP, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines for Mood Disorders.

Treatment strategy for mixed features

The RANZCP 2020 guidelines suggest lithium, valproate and quetiapine as first-line treatments in the initial stage. For the next stage, addressing mixed depression, the guidelines propose adjunctive interventions with aripiprazole and asenapine, supplementary lurasidone for mixed depression and cariprazine and ziprasidone for a non-dominant mixed presentation.Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

Maintenance treatment strategy

In the context of maintenance therapy, the RANZCP 2020 guidelines advocate lithium, valproate, quetiapine, asenapine, and a combination of quetiapine with a mood stabiliser or lithium with aripiprazole as first-line interventions for preventing relapses. Aripiprazole is advised as a principal intervention for preventing bipolar disorder, whereas lamotrigine is regarded as a primary approach for averting depressive episodes.

For the second stage of preventive strategies, RANZCP 2020 suggests paliperidone, risperidone, olanzapine, carbamazepine, two mood stabilisers or a mood stabiliser with olanzapine (or risperidone, ziprasidone) for bipolar disorder prevention. In addition, for preventing depressive episodes, the guidelines recommend two mood stabilisers, a mood stabiliser with olanzapine, or a mood stabiliser with lamotrigine and aripiprazole (or olanzapine, quetiapine, fluoxetine, lurasidone) as a combination therapy. OFC therapy is suggested for potential later interventions owing to its uncertain long-term durability (Table 6).Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

The International Neuropsychiatric Association (CINP-BD 2017)

Treatment strategy for manic/hypomanic episodes

The CINP-BD 2017 guidelines propose first-line treatment of patients with manic episodes using monotherapies such as aripiprazole, asenapine, cariprazine, quetiapine, risperidone and valproate. Sole treatment with paliperidone is also acknowledged as a primary strategy.

The second-line treatments in the 2017 CINP-BD guidelines include monotherapy with olanzapine, lithium, carbamazepine and haloperidol, as well as combination therapy with a mood stabiliser and aripiprazole (or haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone). For secondary interventions, lithium with allopurinol, valproate with typical antipsychotics, a mood stabiliser with medroxyprogesterone, and valproate with celecoxib were recommended. ECT and oxcarbazepine are suggested for subsequent interventions.Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13

Treatment strategy for depressive episodes

The CINP-BD 2017 guidelines propose standalone treatments involving quetiapine, lurasidone, and OFC as the primary interventions for patients experiencing depressive episodes, as indicated in Table 7.

Table 7 Recommended therapies for diverse subcategories of bipolar disorder according to CINP-BD-2017

adj, adjuvant; CINP-BD-2017, 2017 International College of Neuropsychopharmacology treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; LAI, long-acting injectable.

Advancing to the second stage of treatment strategies, the CINP-BD 2017 guidelines recommend several options. These include monotherapies such as valproate or lithium, combination therapies involving mood stabilisers with lurasidone (or modafinil, pramipexole), combined administration of lithium and pioglitazone, and the addition of escitalopram or fluoxetine.Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13

Treatment strategy for mixed features

In addressing the complex landscape of mixed features presentation, the 2017 CINP-BD guidelines designate combination therapy of olanzapine with a mood stabiliser as the primary treatment for patients with mixed features. In the second stage, the guidelines recommend olanzapine, aripiprazole, carbamazepine and valproate for subsequent interventions. The guidelines also propose OFC and ziprasidone as potential strategies for later stages of intervention.Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13

Treatment strategy for rapid-cycling bipolar disorder

The 2017 CINP-BD guidelines establish aripiprazole, quetiapine and valproate as initial treatment options. Subsequently, olanzapine and lithium are suggested as second-line strategies, whereas combinations of mood stabilisers with quetiapine or risperidone are considered for later stages of intervention.Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13

Maintenance treatment strategy

The 2017 CINP-BD guidelines recommend monotherapy with lithium, aripiprazole, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone or RIS LAI as the primary treatment for the first stage of maintenance therapy.

For the second stage, it proposes combinations such as fluoxetine or lithium, lithium with carbamazepine, and the concurrent use of mood stabilisers with quetiapine (or olanzapine, aripiprazole). Additional recommendations include considering RIS LAI, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in subsequent phases of intervention. In this context, antidepressants, paliperidone, valproate and ziprasidone as adjunctive therapies are suggested as potential options for later consideration (Table 7).Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13

Discussion

Management of manic/hypomanic episodes

It has been observed that the NICE 2014 guidelines do not advocate lithium or valproate as first-line treatment options for patients with bipolar disorder.2 Conversely, KMAP-BP 2022, RANZCP 2020 and CANMAT 2018 endorse lithium and valproate as primary mood stabilisers for bipolar patients as part of their first-line strategies.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 Although this variance may have multiple reasons, the focus of KMAP-BP 2022 on a panel of psychiatry experts, offering differentiated recommendations based on evidence and varying in recommendation strength across a comprehensive array of treatments, can be comprehended as a significant reason. Conversely, NICE 2014 seems to streamline suggestions for both diagnosis and treatment. By contrast, BAP 2016 and CINP-BD-2017 recommend valproate as the sole first-line mood stabiliser.Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13 It is apparent that BAP 2016 made this recommendation considering the morphological renal changes that occurred in 10–20% of patients after long-term treatment with lithium.Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24

Across all guidelines, quetiapine and aripiprazole were generally preferred as first-line atypical antipsychotic drugs for manic episodes. Olanzapine was considered as a first-line therapy in the BAP 2016, NICE 2014 and KMAP-BP 2022 guidelines only. It was preferred as a second-line strategy in the RANZCP 2020, CANMAT 2018 and CINP-BD-2017 guidelines.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9,Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 This variation may be based on metabolic side-effects as well as benefits during long-term use. Studies on olanzapine's metabolism in healthy Caucasian, Japanese and Chinese populations revealed no racial differences. However, despite the absence of racial differences, variations in olanzapine recommendation strategies across countries may be attributed to preferences or cultural differences related to side-effects.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Seo and Choo25

Even though haloperidol is recommended in BAP 2016, CANMAT 2018, CINP-BD-2017, NICE 2014 and RANZCP 2020 as a first- or second-line typical antipsychotic drug, KMAP-BP 2022 does not endorse it in either capacity.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9,Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 This difference seems to be related to variations in drug metabolism between Asian and Caucasian populations. Haloperidol-metabolism-related enzymes include CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. In a pioneering study, Potkin et al compared the drug plasma concentrations (Cps) of haloperidol between Chinese and non-Asian American patients; they observed that the Chinese patients, after 6 weeks of administration, had an average 52% higher haloperidol Cps, implying that Asian individuals may require lower doses. In addition, the findings highlight a higher sensitivity among Asian individuals to antipsychotic-induced adverse effects.Reference Potkin, Shen, Pardes, Phelps, Zhou and Shu26 In a study by Lin et al, after administration of a single dose of haloperidol, results showed that White individuals had lower Cps and a less pronounced prolactin response.Reference Lin, Poland, Lau and Rubin27 These research findings suggest contributions from both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors to the response differences between people of different races.

In cases of incomplete response or non-response to the initial treatment, KMAP-BP 2022 recommends transitioning to an alternative drug within the same category, be it a mood stabiliser or atypical antipsychotic. Furthermore, for manic episodes with psychotic features, KMAP-BP 2022 proposes triple combinations, such as mood stabiliser + atypical antipsychotic or lithium + valproate + atypical antipsychotic, as the next stage of intervention. Most of the other guidelines, however, recommend ECT and clozapine, whereas chlorpromazine, clonazepam and tamoxifen receive specific endorsement in CANMAT 2018.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9,Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 This may stem from the cultural tendency in Korea to exhibit a lesser preference for ECT treatment compared with that of Western countries.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Seo and Choo25 However, experts underscore the significance of applying ECT treatment when warranted, drawing support from recent research findings. Anticipations are that forthcoming updates to KMAP-BP will integrate this evolving perspective.

Management of bipolar depressive episodes

As outlined above, in mild depressive episodes, KMAP-BP 2022 advocates monotherapy with a mood stabiliser or atypical antipsychotic as the first-line therapy. In cases of moderate to severe depression and psychosis, the preference leans towards combinations such as mood stabiliser + atypical antipsychotic, mood stabiliser + lamotrigine and atypical antipsychotic + lamotrigine.Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 However, the other guidelines have a comparable focus on monotherapies and combined therapies as the first-line approach for bipolar depression. Furthermore, the first-line intervention outlined in the RANZCP 2020 guidelines involves monotherapy with lithium, lamotrigine, valproate, quetiapine, lurasidone or cariprazine, whereas the CINP guidelines exclusively recommend quetiapine, lurasidone and OFC as first-line interventions.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9,Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 Presumably, the variation in expert opinions and supporting evidence used in the compilation of the guidelines can account for these differences in treatment options. The differences may also have arisen owing to the distinct compilation methods employed, as well as the timing of each guideline.

In mild to moderate episodes, KMAP-BP 2022 recommends aripiprazole, quetiapine and olanzapine as first-line monotherapy or adjunctive therapy. However, CANMAT 2018 and CINP-BD 2017 guidelines classify aripiprazole as a third-line recommendation,Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13,Reference Kim, Bahk, Woo, Jeong, Seo and Choo24 possibly owing to recent studies indicating potential variations in aripiprazole metabolism, especially in relation to racial differences.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Seo and Choo25 The metabolism of aripiprazole involves two enzymes, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Studies of genetic polymorphisms and phenotypes have revealed that the poor metaboliser genotype represents approximately 7.7% of the White population but only around 1% of Asian individuals. Intermediate metaboliser genotypes, numbered from 14 to 15, are predominantly found in Asian populations. For example, a common genetic variant in the Chinese population, CYP2D610, has a high frequency of 64–70%. By contrast, the population frequency of the CYP2D6 intermediate metaboliser genotype in Caucasian individuals is less than 0.5%.Reference Konstantinou, Hui, Ortiz, Kaster, Downar and Blumberger28 Aripiprazole is recommended as a second-line medication in mood stabiliser treatment guidelines, specifically by BAP 2016 and NICE 2014.2,Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9 Recent research indicates a higher prevalence of the CYP2D6 poor metaboliser genotype in populations such as the British (12.1%), Danes (10.6%) and French (9.7%), owing to the frequent occurrence of CYP2D64.Reference Lin29

Restricted use of antidepressants in depressive episodes in a secondary combination therapy is observed across all the guidelines, reflecting associated controversies such as heightened suicide risk and development of mixed or rapid-cycling episodes.Reference Benard, Vaiva, Masson and Geoffroy18 However, this controversy has waned in light of a recent study conducted by Yatham et al. Although the primary outcome did not produce statistically significant advantages, secondary analyses revealed a 40% reduced risk of mood episodes in the bipolar disorder patient group treated with antidepressants. These findings tentatively suggest endorsement for adjunctive antidepressant therapy in bipolar disorder, provided that the potential side-effects are judiciously considered.Reference Yatham, Arumugham, Kesavan, Ramachandran, Murthy and Saraf30

The treatment of depressed individuals, particularly those with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, involves considering the potential impact of CYP2C19-metabolised antidepressants (such as citalopram and escitalopram) on serum levels.Reference Zhang, Xiang, Zhao, Ma and Cui31 This consideration is essential for maintaining a balance between treatment efficacy and side-effects, especially concerning the additional risk of inducing mania in individuals with a predisposition. The search for therapeutic approaches involves ongoing developments in evidence supporting pharmacogenetic-guided therapy, with a primary focus on ensuring drug safety, managing side-effects and promoting treatment adherence. Although the clinical implications of CYP2C19 and serotonin transporter gene mutations remain incompletely understood, a low metabolic phenotype is associated with elevated serum levels and an increased risk of adverse effects. Guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and recommendations by Nassan et al (2016) underscore the importance of cautious or significantly reduced dosing alternatives for individuals with the CYP2C19 poor metaboliser genotype.Reference Zhang, Xiang, Zhao, Ma and Cui31,Reference Nassan, Nicholson, Elliott, Rohrer Vitek, Black and Frye32

On the other hand, modafinil and armodafinil are not recommended under the KMAP-BP 2022 for bipolar depression, as their effectiveness in bipolar disorder treatment remains inconclusive. In Korea they are primarily used in management of hypersomnia.Reference Kim33 However, CANMAT 2018, CINP-BD-2017 and RANZCP 2020 guidelines recommend them as second- or third-line treatments for bipolar depression.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8 CANMAT 2018 suggests armodafinil as adjunctive therapy, with a level 4 recommendation (expert opinion) for a third-line option, drawing from insights of three double-blind randomised controlled trials.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10 Despite two trials yielding unfavourable primary efficacy outcomes, the recommendation is supported by a positive primary outcome in one trial and several positive secondary outcomes. Although modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in a singular trial, its inclusion in the third-line strategy aligns with three negative trials for armodafinil.15 RANZCP 2020 reports a modest benefit for modafinil in major depression based on a single trial.Reference Kaser, Deakin, Michael, Zapata, Bansal and Ryan34

NAC is also recommended as a third-line intervention by CANMAT 2018. According to a randomised controlled study conducted by Berk et al, NAC is a safe and effective augmentation strategy for managing depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Berk, Copolov, Dean, Lu, Jeavons and Schapkaitz35 In the context of Korea, the use of NAC for treating bipolar disorder is not mentioned or recommended. This cautious approach can be attributed to the fact that the scientific evidence supporting the efficacy of NAC is predominantly based on findings from the past decade. Furthermore, the Korean clinical guidelines remain constrained by the limited clinical experience of experts with respect to these recent research outcomes, leading to the presumption that NAC is not recommended in the current version of Korean guidelines.

In the context of bipolar depression, KMAP-BP 2022 proposes adjunctive interventions such as clozapine, buspirone, stimulants, thyroid hormones, ECT and rTMS as third-line treatment strategies. Conversely, other guidelines advocate a broad spectrum of treatments in the third-line category, including carbamazepine (or oxcarbazepine), antidepressants, modafinil, eicosapentaenoic acid, rTMS, ketamine, light therapy/sleep management, levothyroxine, NAC, pramipexole, armodafinil and l-sulpiride.Reference Woo, Bahk, Jeong, Lee, Kim and Sohn1,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Seo and Choo25

The diversity observed in recommended medications and strategies across international guidelines is rooted in the reliance on various clinical trial outcomes. Formulating evidence-based guidelines at each national level requires the conduct of a range of clinical trials, addressing the specific needs of its population and investigating different treatment drugs and methods.

Management of mixed features

In addressing mixed features, KMAP-BP 2022 aligns its recommendations with those for manic episodes, showing a preference for monotherapy. This inclination is consistent with patterns observed in other treatment guidelines. KMAP-BP 2022 designates aripiprazole, olanzapine and quetiapine as the most favoured atypical antipsychotics for managing mixed features. By contrast, other guidelines suggest a variety of atypical antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, asenapine, cariprazine and lurasidone. It is crucial to consider this variation in the context of the Korean setting, where drugs recommended at higher tiers in CANMAT 2021 and RANZCP 2020, such as asenapine, cariprazine and lurasidone, may not have been introduced or approved domestically.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8

Maintenance treatment strategies

KMAP-BP 2022 suggests a range of strategies for maintenance therapy in bipolar disorder, placing emphasis on mood stabilisers, atypical antipsychotics and their combinations. Among these options, valproate, lithium, aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine and lamotrigine are highlighted as preferred choices.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8 However, valproate and lithium, despite their proven efficacies in preventing relapse, are not considered as first-line agents in the BAP 2016, NICE 2014 or CINP-BD-2017 guidelines. The decision may be influenced by factors such as common side-effects (gastrointestinal discomfort, elevated liver aspartate transferase, tremors, sedation) and the need for monitoring in certain populations.Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani9

Olanzapine, on the other hand, receives consistent attention across guidelines, being recommended as a first-line medication for maintenance therapy by KMAP-BP 2022 and CINP-BD-2017.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze, Vieta, Young, Yatham and Blier13 Risperidone has varying status, being a first-line agent only in CANMAT 2018, with subsequent use recommended by BAP 2016, CANMAT 2018 and RANZCP 2020. CANMAT 2018 indicates the efficacy of intermittent intramuscular risperidone in preventing mania and the superiority of 6 months of oral risperidone adjunctive therapy in preventing mood disorders.Reference Yatham, Kennedy, Parikh, Schaffer, Bond and Frey10,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

RANZCP 2020 introduces carbamazepine and olanzapine as primary choices when both mania prevention and treatment of depression are crucial, whereas paliperidone and risperidone are suggested if mania prevention is the primary concern. These recommendations have not been incorporated into KMAP-BP 2022.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8,Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell12

The uniqueness of paliperidone is further underscored by being considered a first-line therapeutic agent solely in CINP-BD-2017, with CANMAT 2018 and RANZCP 2020 suggesting its use at a later stage. Paliperidone's limited approval only for schizophrenia treatment in Korea also contributes to its distinct status.Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8

Limitations of the bipolar disorder guidelines

The KMAP for bipolar disorder was first published in 2002, based on a consensus among Korean psychiatrists. Despite a recent update in 2022, the reliance on expert consensus, using the Delphi technique, remains unchanged. This approach differs from the evolving trend in other countries that have embraced evidence-based methods for developing guidelines. Notably, certain treatment strategies outlined in KMAP-BP 2022 may not be considered as first-line options, even when evidence supports their effectiveness. In addition, the omission of emerging pharmacological agents such as lurasidone, asenapine and cariprazine, which are recommended by alternative clinical practice guidelines, contributes to disparities between KMAP-BP 2022 and its counterparts,Reference Jeong, Bahk, Woo, Yoon, Lee and Kim8 further highlighting the differences between the Korean approach and prevailing international guidelines. As a result, there is a need for re-evaluation.

Conversely, the majority of experimental data in evidence-based guidelines stem from well-designed randomised controlled trials. However, a significant concern arises owing to the potential discrepancy between the outcomes observed in these controlled settings and the complexities of real-world clinical situations. This limitation extends to other guidelines, including BAP 2016, NICE 2014, CANMAT 2018, RANZCP 2020 and CINP-BD-2017. Furthermore, certain guidelines, such as NICE 2014 and BAP 2016, have not been updated for nearly a decade, despite significant advances and discoveries in clinical practice during this period. The static nature of these guidelines raises concerns about their relevance to current advances in the field. Regularly updating treatment guidelines is crucial to ensure that patients receive cost-effective interventions that align with the latest research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have scrutinised bipolar disorder treatment guidelines from diverse regions, including Korea, the UK, Canada, and Australia/New Zealand and from international societies. The identified variations in recommended key medications result from inherent racial variations in CYP450 genotypes, influencing drug metabolism levels and side-effect frequencies. It is noteworthy that methodological differences in deriving treatment recommendations, such as the use of meta-analysis results or reliance on the use of the Delphi technique, contribute to divergent guidelines. In Korea, the current bipolar disorder treatment guidelines rely on expert opinion through the Delphi technique, which may contrast with evolving trends in other nations and result in omission of evidence-based drugs from the guidelines. On the other hand, BAP 2016, NICE 2014, CANMAT 2018, RANZCP 2020 and CINP-BD-2017 are grounded in meta-analysis results and clinical trial outcomes that may be based on rigorously designed randomised controlled trials different from real-world clinical situations. To enhance the scientific foundation and global applicability of future guidelines, it is crucial to establish robust evidence through large-scale clinical trials that address the characteristics of diverse populations. This is essential for confirming both the efficacy of and the potential risks associated with specific medications, ensuring that recommendations are not only contextually relevant but also widely applicable.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (NRF-2020R1A2C2103067), as well as a Duksung Women's University Research Grant (2023-3000008029).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.