Maud Wood Park, a twenty-nine-year-old Massachusetts teacher, Radcliffe College graduate, and state suffrage organizer, attended a National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention in Washington, DC, in 1900 at a pivotal moment when the group was about to enter a period of change to recruit younger, more respectable, and better-educated members. The meeting, which marked nineteenth-century women’s rights pioneer Susan B. Anthony’s eightieth birthday and her retirement as NAWSA president, included many rousing tales of past battles for women’s right to vote. A particularly notable event for Park was when Anthony introduced new NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt, transferring leadership from one generation to the next.Footnote 1 Park returned to Massachusetts inspired by her experiences and the promise of a new generation continuing the fight for women’s suffrage. She believed that younger women like herself, her colleagues, and her students were vital to the campaign. Their organizing would see suffrage through to a full national legislative victory, honoring earlier activists’ work and ultimately creating more opportunities for women in the public realm.

Park, determined to mobilize the nation’s white, elite, and college-educated men and women to the suffrage cause, invited fellow Radcliffe alumna and teacher Inez Haynes Gillmore to organize the College Equal Suffrage League (CESL, a NAWSA affiliate). The CESL would begin to campaign among college and university alumni, eventually turning to students at select prestigious institutions.Footnote 2 Initially, however, the CESL faced opposition when they went to campuses. Many administrators feared that on-campus suffrage organizing would damage their institutions’ reputations among students’ parents, donors, and the public. Some academics and students thought suffrage was, at best, merely a distracting and marginal cause; however, the CESL eventually overcame such resistance. It established clubs at many colleges and universities by reframing its organizing principles to conform with academic culture and the reform-minded progressivism common at many elite, white institutions. At institutions where active suffrage clubs inspired by the CESL formed—including Radcliffe College and Harvard University in the North, Newcomb College and Tulane University in the South, and the University of California at Berkeley in the West—campaigners harnessed the power of education in their activism as a tool to further their political goals. As a result, the CESL and its members contributed significantly to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Organizers turned campuses into training grounds for new, young activists, generating more widespread support for the suffrage movement in the process. Middle- and upper-class white American voters now saw suffrage activists who they considered respectable—young, white, elite, and well-educated. The campaign of these suffragists was more difficult for voters to ignore. The CESL’s campus activism also created an example for future campaigners and laid the groundwork for on-campus women’s organizing in the decades that followed.

This study of Maud Wood Park and the CESL’s college and university campaigns provides a new perspective on the women’s rights movement, student activism, and higher education at the turn of the twentieth century. Most work on organized women’s rights activism on college and university campuses is focused on the 1960s and 1970s. Scholars link this activism to other social movements, such as the New Left, the anti-war movement, and the civil rights movement; they ignore the earlier, vibrant history of women’s campus activism. This study argues for a longer legacy of organized women’s rights campaigns on campuses that grew out of the broader ideologies of progressive reform. It fits among recent scholarship that reframes the trajectories of social and political movements and pushes the timelines backward by considering the organized activism for women’s rights on campuses that came before what scholars have termed the “second wave” of the women’s rights movement.Footnote 3

Many scholars have underemphasized the importance of campus suffrage organizing during the Progressive Era due to the grassroots and small-scale nature of the campaigns. Suffrage clubs on campuses were often limited in membership and typically generated little publicity outside college and university publications and NAWSA records. These organizations are also often overlooked by scholars due to assumptions about hostility to radicalism on university campuses during this period. Scholars who overlook the CESL’s full scope of activism suggest that there was particularly little support for suffrage at coeducational schools and even some all-female colleges because administrators already faced criticism for educating women. Some studies mistakenly contend that if interest in suffrage was present on any campuses, it was only at certain schools—in particular, the “Seven Sisters,” with their large communities of female administrators, faculty, and students who were supportive of sex equality in earlier periods.Footnote 4 However, these studies overlook the broader range of college organizing, including much of the work initiated by groups such as the CESL and college and university activism at other well-established men’s, women’s, and coeducational institutions both inside and outside the Northeast. The success of the CESL in particular reveals a more expansive student campaign and an unexplored dimension of progressive reform headed and enacted by younger generations, particularly college-educated women (and sometimes even the children of mainstream social reformers and political figures). Though routinely overlooked by scholars, these campus activists generated ripples and trends that had significant long-term effects.

The new leaders of the women’s suffrage movement were responding to an era of stagnation by reorganizing and innovating when Park and Gillmore began the CESL in 1900. The NAWSA, the group most closely associated with the CESL, had been created in 1890 with the goal of campaigning for women’s right to vote at the state and national levels. Many of the original leaders were older women who had been active in the abolition, women’s club, and other reform movements of the nineteenth century. They came to the campaign from various educational backgrounds and with diverse activist experience. Their methods, informed by their early reform work, focused on strategies such as petitioning the government, writing to politicians, and speaking at relevant meetings. They achieved early successes in expanding women’s educational access, securing protective labor legislation, and changing suffrage laws at the grassroots level in areas such as school elections.Footnote 5 The cause’s visibility and urgency, however, was fading by the turn of the twentieth century. Many of the suffragists who had spearheaded the nineteenth-century movement were stepping down or dying. The deaths of several prominent suffragists—Lucy Stone in 1893, Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902, and Susan B. Anthony in 1906—left the campaign without some of the most respected leaders.Footnote 6 Progress stalled as the number of experienced organizers dwindled. Four states had granted women’s right to vote before 1900, but grassroots victories dried up. No additional states passed women’s suffrage legislation from 1896 to 1910.Footnote 7 Suffragists made no noticeable progress at the federal level.Footnote 8

Carrie Chapman Catt, as the newly elected NAWSA president, planned to improve the movement by professionalizing and legitimizing the modern suffrage campaign. This meant, for Catt, gaining support among Americans whose allegiances she felt would do the most to further the cause: white middle- and upper-class citizens with financial, cultural, and political power.Footnote 9 Suffragists sought new audiences and spaces to broaden their support base during the period; this included arranging new protests in public parks; campaigning in city, suburban, and rural streets; and speaking in government halls in the North, South, East, and West.Footnote 10 NAWSA leaders over time recognized campuses too as another possible stage upon which to generate more respectability and promote greater unity among targeted men and women and existing suffrage supporters.Footnote 11 The NAWSA, under Catt’s leadership, increased from 17,000 to over 200,000 members by 1916 and included a larger number of affiliate branches that spoke to different localities and interests, such as the CESL. The number of states that supported women’s suffrage climbed from four to twelve.Footnote 12 These changing trends and demographics raised the upper classes’ awareness of and respect for the organization and its branches.

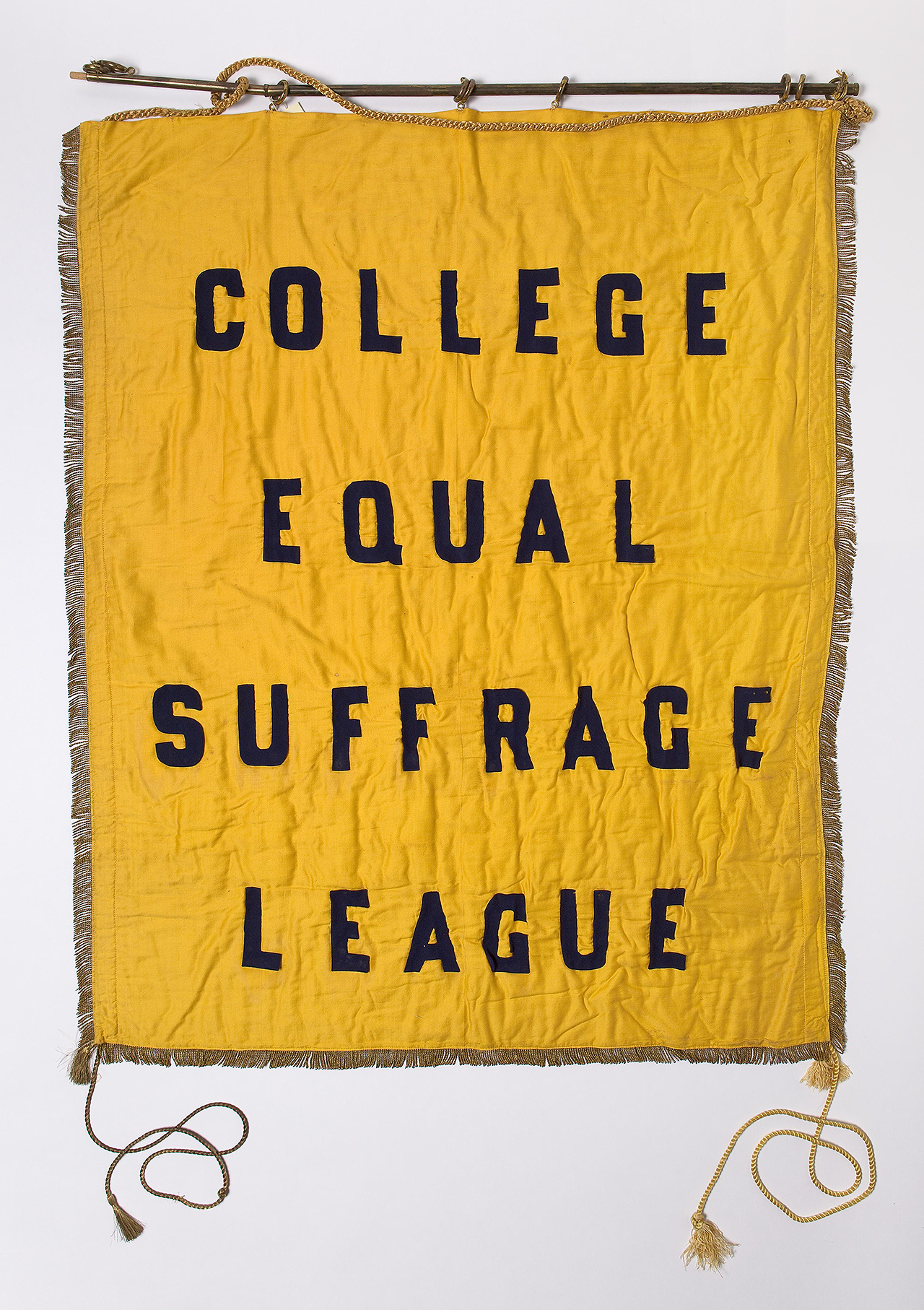

Most college and university campuses in the United States had no significant, organized pro-suffrage presence before CESL-inspired clubs and organizations were established. Many state and national suffragists, including CESL leaders, had traditionally dismissed campuses as viable campaign spaces because they encountered considerable apathy and opposition there. Few college and university administrators, faculty, or students identified as advocates of women’s right to vote because of the controversy surrounding the women’s suffrage issue and the pressure to maintain respectability. Today’s colleges and universities are often seen as hubs of liberalism and protest. College and university culture, however, in the early twentieth century was caught up in the same transitions seen in society as a whole, where old ideals were beginning to mix with new. Lingering Victorian gender expectations that suggested a woman’s natural place was in the home and subservient to her husband contributed to negative and indifferent attitudes toward women’s suffrage on most campuses, as these ideas were upheld by many administrators, faculty, and guardians of students. Many Americans viewed women’s rights activists as unfeminine spinsters determined to upset the order of the family and the nation when the CESL began in the early 1900s. These same Americans were similarly skeptical of the growing number of college women and feared that association with the women’s suffrage movement would tarnish their or their children’s personal and professional reputations. Even the forward-thinking educators and students who supported equal college and university training for both sexes believed endorsing female advancement in academia was controversial enough without adding support for women’s right to vote, which they argued would further influence their public appearance as being possibly “too” progressive and hinder the goals of their larger scholarly campaigns (fig.1).Footnote 13

Fig. 1. College Equal Suffrage League banner. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The CESL, an organization specifically designed to rally support among Americans with higher education, avoided campaigns among students on school grounds for its first five years. Park and Gillmore advised CESL activists to begin organizing among college-educated Americans by recruiting literate, articulate, well-connected alumni in urban centers (creating alumni leagues in cities). The CESL’s first branch, formed in Boston in 1900 with a charter membership of twenty-five supporters, attempted to gain greater backing not with students but among the graduates of colleges and universities living in and around the city.Footnote 14 The other CESL alumni branches that these leaders formed in urban centers across the United States planned to work with state suffrage organizations associated with the NAWSA to bolster existing grassroots campaigns by first rallying college graduates working as lawyers, doctors, educators, social reformers, and scientists, and, in doing so, adding a pool of easily accessible, publicly respected, and well-educated recruits. It is possible that suffragists viewed the CESL as another strategy to advance Catt’s “Society Plan,” which drew more upper-class Americans to the movement and improved the respectability of the cause.Footnote 15

Northwestern University undergraduates formed a university suffrage club in 1905 and requested affiliation with the CESL.Footnote 16 This motivated Park and Gillmore to reconsider the usefulness of campuses in connection with the women’s suffrage movement and encouraged the league to send activists to school grounds to organize students.Footnote 17 The CESL created more college chapters that would work with alumni leagues and NAWSA’s state and local sections to expedite women’s right to vote after this shift in perspective. The organization campaigned at coeducational institutions and men’s and women’s colleges. It formally included and encouraged the development of college men’s leagues. Almost all of the CESL’s key leaders were women. Men from these groups, however, often represented the CESL as orators and organizers, especially on campuses and in cities following the women’s direction. The CESL was not a single-sex organization; possibly, it recognized the value of winning recruits among the next generation of male voters too. Male chapters participated in the same types of activism as female groups, advancing the larger educational objectives of the CESL and the NAWSA and appealing to a similar crowd. The CESL had expanded so greatly by 1908 that CESL leaders created a national umbrella branch to oversee the work of these smaller sections and standardize the college campaign. The national body kept a list of suggested speakers and tactics, helped with financial costs, and provided literature to support the efforts of grassroots branches, among other activities.Footnote 18 The national CESL, despite its intent, was the most short-lived and unstable of the group’s sections because it lacked effective communication and a unified vision.

Park and Gillmore carefully selected and approved a list of sites for campus mobilization to ensure that their organization would maintain its goal of establishing respectability and reach its target audience of elite white Americans. These respected and well-established schools predominately served a white middle- and upper-class student body. The CESL sent no organizers to historically Black colleges and universities, and there is no documented evidence that the CESL included African American campaigners in the group’s ranks, leagues, or chapters.Footnote 19 African American college students did participate in the suffrage campaign at historically Black colleges, universities, and institutes during the period via their own campus organizations and social and political groups. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, as well as Black sororities and faculty groups, promoted women’s suffrage and included college-educated African Americans in their membership during the Progressive Era. Students and faculty, for example, at the Tuskegee Institute, Howard University, and Lincoln University of Missouri were involved in suffrage activism on and off campus.Footnote 20 This activism was not collaborative with the CESL and did not occur on the same timeline, in the same spaces, or for the same reasons, as Black women’s goals, strategies, and motivations in organizing for the vote were based on multiple layers of discrimination. It is possible that the CESL, like other NAWSA associated organizations, feared complicating their movement by associating their campaign for women’s suffrage with African American equality. The group, similar to other mainstream white suffrage bodies, may also have feared losing support in the South, where racism remained deeply entrenched in the dominant culture.Footnote 21 Although Catt did personally support African American rights, she and other leaders of her race often put aside additional objectives they believed in, including civil rights, to promote advancement for their sex first to keep the suffrage cause popular among the white upper classes nationwide.Footnote 22

One of the first challenges the CESL faced on college and university campuses was convincing administrators, faculty, and students that its organizers belonged, its cause was worthwhile, and its clubs deserved a place. CESL leaders recognized that “the conditions of academic work” made it “desirable” for campus chapters to focus on “educational rather than [purely] political” goals, such as promoting the study of citizenship rights and women’s suffrage versus encouraging the students to lobby the government.Footnote 23 Park emphasized that the CESL would represent a “new order” of well-dressed, articulate, intellectually sophisticated activists to appeal to the sensibilities and values of the mainstream academic community and the culture of progressive reformers just beginning to accept bolder, equally educated women.Footnote 24 League members aspired to add new “intellectual prestige” to the women’s rights movement at the turn of the twentieth century when suffragists desperately needed to reshape the image and support base of the campaign if they hoped to keep their cause alive.Footnote 25 Students announced that their organization would be a respectable scholarly group that planned to commence “a systematic study of the problems of women and the ballot” when the University of California, Berkeley, branch of the CESL was established in 1909.Footnote 26 Students declared that membership in the society did not necessarily mean one was pro-suffrage, but that one might be interested in the issue of women’s right to vote like any other topic of past or present debate and discussion.Footnote 27 Leaders of the Newcomb College suffrage club in New Orleans publicly stressed their scholarly ambitions when they formed their campus association in 1914.Footnote 28 The suffragists explained in local newspapers they intended to avoid what they perceived as the unneeded “violent, sensational measures” used by outside organizations to advocate for their cause to calm any fears in their conservative Southern community.Footnote 29 This club and others would promote women’s suffrage and encourage academic analysis of women’s rights issues in a “sensible way,” and held steadfast to the approach even as the CESL’s activism increased in the early 1910s.Footnote 30

Popular methods of on-campus activism included scholarly competitions involving the research, writing, and oratory debate typical of the collegiate and larger political culture. These competitions offered interested undergraduates intellectual and financial incentives for studying the history and literature of the suffrage movement.Footnote 31 Harvard men and Radcliffe women from the suffrage and the anti-suffrage chapters of the Civics Club participated in many single-sex oratory contests, as did students from Newcomb and Tulane, who even partook in coed debates against one another. Victorious teams were noted in college publications and city newspapers. Local CESL or NAWSA suffragists sometimes served as judges at these college contests. Student participants occasionally were invited to speak at state suffrage conventions.Footnote 32 Some student debates on suffrage brought together undergraduates from several schools for larger intercollegiate contests, particularly at bigger public institutions. University of California, Berkeley, debate teams, for example, repeatedly went up against students from nearby rival institutions, such as Stanford University, on the question of women’s right to vote.Footnote 33 Oratory contests on campuses legitimized the discussion of women’s right to vote among students and faculty and challenged students to think critically about the campaign and related trends in the larger culture. They engaged students in viable organized discussions about women’s rights as part of the academic experience often for the first time.Footnote 34

The CESL’s early activism also focused on hosting pageants and plays, besides oratory and writing contests, to teach about the women’s suffrage issue in entertaining ways and capitalize on female college students’ growing interest and involvement in drama and the arts. These suffrage plays in reality were a strategic educational tool used to awaken interest in and enlighten the public about the cause rather than merely frivolous amusements. Many Americans among the middle and upper classes still went to the theater as a primary source of entertainment during the early twentieth century, making it an effective way to reach the masses. Students participating in the productions learned about the key activists who promoted women’s right to vote, prevailing arguments and attitudes toward the issue, and the history of the movement as they prepared for their roles. Audiences attending the theatrical productions laughed, cried, and were emotionally and mentally drawn into the plot, being entertained, all while learning about the movement. For example, UC Berkeley students and local suffragists put on a pageant called “Woman in History” in the fall of 1911, which was produced by the nearby alumni chapter of the CESL at Piedmont Park.Footnote 35 Student supporters and off-campus activists from many colleges and universities in Massachusetts, Louisiana, California, and other states also produced versions of classic suffrage plays, such as “How the Vote Was Won,” for their colleges and communities, as well as shorter skits during smaller school events.Footnote 36 Newcomb students staged a humorous performance at a collaborative intercollegiate social event called “Tulane Night” that included a suffragist preaching about “votes for women” to a college girl, causing her to become interested in women’s rights and, subsequently, campaign for a female representative to be elected to an academic board.Footnote 37 These productions introduced students to the movement in nonthreatening and humorous ways, bolstering morale for and inspiring curiosity about the women’s rights cause (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Radcliffe College students handing out suffrage flyers in Massachusetts. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The CESL’s state and national representatives and its student members additionally held public lectures to educate about their agenda, challenge ignorance and stereotypes, and raise awareness about their political issues like other Progressive Era educators, reformers, and activists during the period. NAWSA leader Carrie Catt was especially concerned about creating new activities to help reshape the image of the campaign and its proponents, and had been consistently encouraging suffragists’ characterization as “the better elements in society” through various avenues, promoting appropriate conduct and discipline as necessary for victory.Footnote 38 Her ideas influenced Park and the CESL even when she stepped down briefly as the major NAWSA campaign leader. The CESL’s campus-respectable presentations helped to offer a necessary counterimage of the modern suffragist alongside the efforts of other NAWSA organizers in the minds of administrators, and college students and their families when the campaign was heating up in the United States and abroad by the 1910s and the British suffragettes were capturing media attention and drumming up controversial publicity for the movement with their violent and destructive protests in the United Kingdom. The CESL only sent lecturers to campuses whom they felt could serve as role models for the students to provide a contrast to the European organizers they read about in the newspapers. Lecturers needed to exhibit suitable appearance, behavior, and credentials to earn approval for campus deployment. The CESL commissioned seasoned suffragists with impressive résumés to speak at American universities instead of inexpensive novices. Students at Radcliffe, Harvard, Newcomb, Tulane, and UC Berkeley heard presentations from well-regarded campaigners, including Anna Howard Shaw, a NAWSA leader; Florence Hope Luscomb, the executive secretary of the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government (BESAGG); and Maud Younger, a respected suffragist from California who supported voting rights for working women.Footnote 39 Harvard suffragists openly declared that their campus organization screened guests vigorously to ensure lecturers were of the “highest character and intellect.”Footnote 40 Campus suffragists recruited “authorities in the field.”Footnote 41

Guest speakers addressing students also frequently turned to tried-and-true familiar academic subjects such as history and science to bolster the women’s suffrage cause and gain acceptance on campus like most NAWSA speakers, rather than relying on nuanced and contentious perspectives. Popular Southern social reformer Kate Gordon delivered an address for students from Tulane and Newcomb in 1911, for example, entitled “Millstones and Milestones,” which sketched the sweeping history of women’s changing position in society from ancient times to the present and emphasized how far women had come and how far that they still needed to go on the path toward greater equality. Gordon identified “milestones” like the removal of barriers to women’s entrance into higher education as female progress, and “millstones,” or moments of “ignorance” and “prejudice,” that held them back.Footnote 42 Gordon was particularly known for her racially charged arguments and stance against a federal women’s suffrage amendment in preference for state-by-state action, which made her controversial to some Americans. These arguments are not evidenced in Gordon’s college presentations or work with the CESL. The contentious perspectives and boldness that kept her popular and influential in areas of the South, however, eventually caused tension with the larger NAWSA, which represented suffragists from all regions and backgrounds, including CESL members. She ended up, in response, founding her own suffrage group called the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference composed of well-educated upper-class white women to support her ideologies.Footnote 43

Other CESL supporters were vocal not only about the movement’s progression and timeline but also the similarities between older and newer arguments used against granting women’s suffrage to emphasize that the nature of the opposition was dated and archaic. One activist commented, “The same arguments were used against the higher education of women as are now being used against giving them the ballot.”Footnote 44 Analogous arguments had also prevented women from entering the professional and business worlds.Footnote 45 NAWSA leader Anna Howard Shaw told Newcomb students that when she was a theological student, she repeatedly heard the traditional contention, “God did not want women to preach.” She emphasized that opponents, especially those in the South, still used religious arguments to bar women from greater opportunities and rights and justify their subordinate status in society.Footnote 46

CESL suffragists on campus tried to give greater attention to arguments that showed that the movement for women’s rights was not unique, but part of a larger, preexisting, and ongoing struggle for the equal treatment of all oppressed people to further broaden their cause and make relatable connections to history—an argument also embraced by former NAWSA president Carrie Catt.Footnote 47 The women’s rights cause could be linked to long-standing class struggle, the struggle of ethnic and religious groups, and the abolition movement, but suffragists were careful to discuss their campaign not as a “revolution” but rather “reform,” to distance their activism from controversy.Footnote 48 They fit the campaign for women’s suffrage, in particular, within the larger social and, later, progressive reform agendas that had been gaining popularity among the upper classes since the rise of the late nineteenth-century settlement house and club movements. Women’s right to vote would be a tool to achieve other changes advocated by educated men and women of the upper classes hoping to improve society, such as campaigns against poverty, poor health, vice, addiction, gambling, filth, white slavery, child labor, and unjust working conditions, according to suffrage speakers.Footnote 49

Another related yet more nuanced component of college lecturers’ academic appeals involved employing a strategic argument dubbed by CESL leaders as “the obligation of opportunity” rationale to target college women. This line of reasoning, initially proposed by Gillmore and consistently applied by Park, stressed that college women owed their academic opportunities to the pioneering women’s rights activists who came before them, and that female students should participate in the suffrage movement to repay these earlier activists for their efforts.Footnote 50 Activists convinced and inspired students at Newcomb to support suffrage in 1909 and 1910 by educating them about the struggles of early women’s rights organizers, who were also advocates of the vote, to gain college and university degrees. They spoke of notable campaigners, such as Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Blackwell, who overcame great adversity in their quests for higher education. Speakers noted, “It was just as unthinkable as if she had aspired to be president,” when Stone first sought to enroll in college.Footnote 51 College leaders barred her from various privileges on campus, such as reading a commencement address, because of her sex.Footnote 52 Blackwell encountered similar challenges during the Victorian era when she pursued medical training. She applied to twelve programs before eventually gaining admission to Geneva College in New York, where she confronted continued prejudice.Footnote 53 Fellow female students who lived in her building often refused to sit at the same table because they claimed that she lacked “all womanly delicacy.”Footnote 54 Early activists such as Stone and Blackwell suffered “social crucifixion” to create change for American women.Footnote 55 Current generations of students, the CESL contended, owed it to them to give back by helping to push the women’s rights movement forward, starting with equal suffrage in the new era. Suffrage orators made powerful, compelling arguments on campuses for support based on the supposed implications of cross-generational sisterhood by educating students about the groundbreaking efforts of the women who came before them.

College spokespeople and other supporters of the suffrage campaign gained further allies in higher education by working to debunk the “scientific” and “biological” claims against giving women the right to vote popular in the late 1800s and still somewhat influential among Americans in the 1900s, particularly among opponents in academia actively working against the cause. Progressively-minded faculty advocates were asked to draw on their expertise to testify that the historically alleged weaknesses in women’s minds and bodies used to argue that they were unfit for politics were false, as the NAWSA allies had, for many decades, been contending. Professor Albert Bushnell Hart of Harvard University asserted in 1913 that based on his professional experience, there was no such thing as the “feminine mind.” He found his female students at Radcliffe just as competent as their male counterparts at Harvard.Footnote 56 Student suffragists pointed to the many examples of women all around them within their families and communities, friends, mentors, instructors, superiors, and loved ones, who had already been learning about history, science, and contemporary issues in the classroom for decades, becoming literate, worldly, and knowledgeable. This training had not hindered their femininity, as adversaries claimed. Many were happily married or respectable mothers, daughters, and members of society. Studying current politics thus would not cause women to “lose a bit of gentle manners.”Footnote 57 Campaigners cited progressive moments and precedents in terms of expanding women’s status and rights, which had shown women’s stamina and readiness for greater public engagement at crucial moments in the country’s history, and emphasized that in all instances, a women-expanded public role helped rather than hindered the cause. Women had already stepped into the public sphere to help men, the government, and the nation during various military engagements, including the American Revolution and Civil War, and nothing bad had come of this extension of gender roles.Footnote 58

Activists asserted bluntly that times were changing and the Victorian housewife should no longer be held as an ideal for college-educated women. One appealed directly to Radcliffe students, saying, “The day of the clinging vine has passed: the new democracy brings with it the independent woman.”Footnote 59 Some CESL speakers noted that many college- and university-educated women might be self-supporting in the new era, or engaged in contemporary, companionate-style marriages on more equal terms with men. Securing the vote could mean a pathway to legislative change that would lead to new or better occupational opportunities and more equitable social and civil rights for this new generation of professional women “coming of age” and more involved in public life and egalitarian relationships.Footnote 60 American suffrage orators often rounded out their claims for support by reminding academic audiences that granting women’s suffrage was inevitable, modern, and progressive, and, thus, they were backing a necessary movement and the winning cause.Footnote 61

Suffragists chose rhetoric and arguments that would best fit the campus climate and culture of higher education where they were speaking and presenting. This approach, which tailored their arguments to their audience and stage, won supporters, but scholars concede that it also created some shortcomings. One of the biggest issues with this strategy was that, by the second decade of the twentieth century, the organization had no “universal body of doctrine” on which to base its claims to all parties it targeted. Activists sometimes used contradictory arguments to appeal to different groups. This practice prevented true national unity among members in the movement, cultivating divisions and factions. Upper-class activists backed the movement for different reasons than lower-class supporters. Suffragists blamed the slow progression of their movement on everything from corrupt politicians to big businesses to uneducated immigrants, for example, depending on their audience.Footnote 62 Working-class women sometimes were allies and sisters in the struggle, and at others, upper- and middle-class women were superior and deserved the vote first because of their literacy and cultured backgrounds.Footnote 63 The vote was described less as a right and something that everyone should be entitled to, depending on the audience, and more as a privilege that should only be extended to certain groups, specifically educated, elite, moral, native-born white women.Footnote 64 Many NAWSA activists embraced middle- and upper-class mores, making it difficult for them to relate effectively to working-class audiences, even when efforts were made to unite.Footnote 65 The vote became less about change and more about providing another tool to help the upper classes preserve the status quo for some NAWSA activists over time.Footnote 66

Fragmentation and variance had only heightened after Catt stepped down as NAWSA president in 1904 and was replaced by Anna Howard Shaw until 1915. Shaw placed even more focus on gaining new members and securing women’s suffrage by any means necessary.Footnote 67 Some scholars have criticized Shaw. They argue that she was not as dynamic a leader as Catt and that she failed to help the NAWSA articulate a clear ideology. Suffragists associated with the organization (including CESL members) were increasingly defensive and reactionary while she was president, spending too much time responding to or attacking their opponents, rather than crafting a persuasive stance to endorse the vote.Footnote 68

Catt’s leadership of NAWSA had left a significant imprint, however, and her initiatives did not completely fade. Her example helped modern American suffragists, like Park and members of the CESL, to develop, among many things, an understanding of and connections with the international movement for women’s rights. Catt had played a key role in developing the International Woman Suffrage Alliance; she traveled abroad, becoming an ambassador for the movement, and laying the groundwork for other American activists.Footnote 69 Park watched Catt’s actions and studied the international conditions women faced; this encouraged greater vehemence in emphasizing the persuasive and educational value of making connections between the suffrage movement in the United States and other women’s rights campaigns worldwide.Footnote 70

The CESL invited foreign suffragists to speak by 1909 to make the US movement seem less isolated and extraordinary to students first encountering the issue. Campus speeches by lecturers from Europe helped to frame American activism in a broader context, allowing students to see parallels between the status, treatment, and goals of women in many countries. The CESL’s international recruits over time often represented non-militant English women’s rights organizations, as they could provide a further tangible contrast to the suffragette activism overseas by discussing ordinary, mainstream British campus campaigns. They supported larger NAWSA efforts emphasizing that aggression and violence were not the norm among typical activists in doing so.Footnote 71 CESL branches collaborated with the English Cambridge University Women’s Suffrage Society (CUWSS) to educate students. English cousins Rachel Costelloe and Frances Elinor Rendel toured the United States extensively to represent the CUWSS at American colleges and describe its work for women’s rights.

Costelloe and Rendel applied many oratorical strategies to improve the image of the women’s suffrage campaign as it heated up by the 1910s. They explained that the controversial suffragettes overseas were a minority in the United Kingdom and that most British activists adhered to the same political style as their American counterparts. Costelloe insisted at Tulane that she was “a peaceful, ladylike suffragist” who never courted arrest or stormed the House of Commons, unlike the reports of the more radical British campaigners.Footnote 72 Costelloe claimed that to establish credibility, she and her allies esteemed “reason” and “persuasion” over violent or destructive demonstrations.Footnote 73 The cousins allayed concerns by describing nonthreatening suffrage activism in Britain, including caravan rides through the English countryside.Footnote 74 Costelloe even blamed newspapers and magazines for exaggerating activists’ capacity for trouble. Often onlookers were the ones who triggered chaos during political events or public demonstrations. She explained, “A little woman would stand quietly at the end of the hall and exclaim: ‘Votes for women!’”Footnote 75 Any ensuing commotion or disorder was the result of unruly civilians who responded.Footnote 76

Most campaigning continued to involve education-oriented tactics and did not move to more aggressive or disruptive protests to secure the right to vote as negative attitudes toward suffrage activism at colleges softened and full voting rights for women seemed more likely in the United States, even in the wake of early state victories in California in 1911 and New York in 1917. Advocates often promoted the ratification of federal rather than state suffrage amendments in places where suffrage passed before 1920, but the focus remained on respectably raising awareness and knowledge at colleges and universities. Tactics included finding new and informal ways to influence the curriculum so it focused on women’s rights and holding extracurricular courses to train women in political organizing and, eventually, the skills needed to vote and lobby. Suffragists built traveling and club libraries with literature on the women’s rights movement and made them accessible to students; they also donated books to public and campus libraries and recommended important texts for female students and the literate public to read. Newcomb suffragists received permission to place reading lists of suggested women’s rights literature directly in their institution’s library.Footnote 77

These actions mimicked the broader methods of the NAWSA in states and localities. Radcliffe students, for instance, arranged an extracurricular, noncredit class on street speaking as part of the Civics Club’s winter agenda in 1917 to educate young aspiring activists. Students practiced lecturing to veterans on issues such as “Earliest Demands” for women’s rights, “Women’s Rights,” “National Suffrage,” activism in “The British Empire,” and “Testimony as to Results” of the campaign.Footnote 78 Participants learned how to refine their arguments, as well as the voice projection, body posture, and facial expressions necessary for taking on more active political roles at the suffrage oratory class.Footnote 79 Campus-speaking classes for young suffragists and students interested in activism sometimes evolved into larger suffrage “schools,” offering training during the summer and winter breaks both on and off campus. These schools encouraged recruits to participate in grassroots campaigns, and they ran with the help of several women’s rights organizations, including the CESL’s alumni and national bodies.Footnote 80 Student suffragists became more involved with college political events over time, such as mock conventions, elections, and straw polls. Participation in these events remained predominately for educational purposes rather than for clearly political reasons (i.e., fighting to support a party). CESL campaigners recognized that this involvement offered a more practical knowledge of government and a better-developed understanding of the responsibilities of full citizenship—increasingly important with women’s suffrage on the horizon.Footnote 81

The organization faced challenges, however, that did threaten the group’s activism by the 1910s, despite the continuous and seemingly successful grassroots educational activism stimulated by the CESL on campuses in the early twentieth century. The CESL’s structure changed; principally, the national branch voted to disband in December 1917, allegedly and publicly arguing that it had reached its goal of raising awareness of the issue among Americans in higher education.Footnote 82 CESL leaders pointed to the advocacy for women’s suffrage by many major respected academic groups, such as the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, as “proof” of the victory in higher education.Footnote 83 The league cited the organization’s impressive membership figures as further evidence it had helped women’s suffrage become a respectable cause among college-educated Americans. It supervised fifty-one college and alumni sections and had enrolled over five thousand suffragists nationwide when the national league disbanded. The group had grown from one alumni league in Boston in 1900 to registered affiliates across the country. The organization had often inspired the development of related local student clubs or committees in a state association that remained independent from the CESL even in places where official affiliates did not exist but was visited by college league orators or representatives.Footnote 84

The public reason given for the dissolution was that the organization had successfully garnered the desired support at colleges and universities, but many unpublicized internal factors contributed to its termination. Leaders complained about financial difficulties, power struggles, and organizing failures. Reports showed that in 1916, the national league faced challenges in raising the five thousand dollars it needed to cover the expenses of its annual activism.Footnote 85 Vice presidents and executive officers skipped meetings because of internal divisions over the CESL’s campaigns, weakening leadership and cohesion.Footnote 86 The US’s entry into World War I (WWI) in 1917 took a significant toll on recruitment and activism, and some students and alumni argued it was inappropriate to advocate for women’s suffrage during the military crisis, while others complained that the group was not doing enough and departed for the more militant National Woman’s Party (NWP) and its controversial protests outside the White House to support the right to vote.Footnote 87

Catt, who reclaimed the NAWSA presidency in 1915, was especially critical of the NWP’s methods, viewing their combative behavior and lack of decorum as a possible deterrent to the success of the movement. She did not support the militant tactics of the British suffragettes who inspired the work of the NWP and did not view these women’s methods as an appropriate direction for successful campaigners.Footnote 88 She did not approve of the NWP’s involvement in partisan politics either; the NAWSA maintained that it did not promote any specific political party but supported suffrage more holistically.Footnote 89 NAWSA and the NWP also had different opinions about what the ideal contemporary woman should strive to be like, with the NWP idea being much more radical and nontraditional and the NAWSA arguing for an extended civic role but not the abandonment of many principals of Victorian womanhood.Footnote 90 NWP leader Alice Paul was much less concerned about respectability, decorum, and good manners than Carrie Catt; she focused on gaining media attention via any route.Footnote 91 Some students and CESL members found messaging from the NAWSA and its affiliates alienating and outdated as a result of these differences. Inez Haynes Gillmore switched to the NWP, for instance, a major loss for the CESL, claiming she had lost faith in the NAWSA, despite being one of the college league’s prominent early leaders.

Maud Wood Park did not even remain fully committed to the CESL, though her reasons were different. Park did not ally with the NWP; instead, as her reputation as intelligent lobbyist grew, she was pulled into other grassroots and, eventually, national positions in NAWSA’s suffrage organizing. Park must have seemed to Catt like the ideal spokesperson for the movement, destined for leadership: she was an educated middle-class woman with an intellectual and dignified, yet refined and feminine demeanor. Park divided her attention between the CESL, the BESAGG (of which she was a founder), and larger campaign work in Massachusetts for the state suffrage referendum as her prominence increased. She also accepted a leadership role in 1916 as the chair of the NAWSA’s Congressional Committee in Washington, DC. The Committee was formed to urge Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment; this role took up the bulk of her time in the movement’s final moments.

State and campus sections of the CESL in many areas voted against disbanding after the national body of the college league broke up in 1917. Many student suffrage organizations continued to run their campaigns, participating in war work that supported state and national NAWSA organizations but in more direct ways. Catt had encouraged this change in direction to focus on both suffrage and war work in all associated organizations by this point. She recognized that women’s war work could respectably increase publicity for the suffragists despite being a pacifist. She believed the war could provide another opportunity to disassociate from the contentious image of the radical modern suffragist that permeated popular culture as a result of the NWP’s work and the behavior of British suffragettes.Footnote 92 Catt and NAWSA’s priorities had shifted by 1917; any continued work for state suffrage needed to occur in strategic locations where victory was likely, or it seemed that activists might actually succeed in influencing both the public and politicians. This was part of the “Winning Plan” that she and other NAWSA affiliates, such as the CESL’s state and local branches, took up as a path to legislative victory.Footnote 93

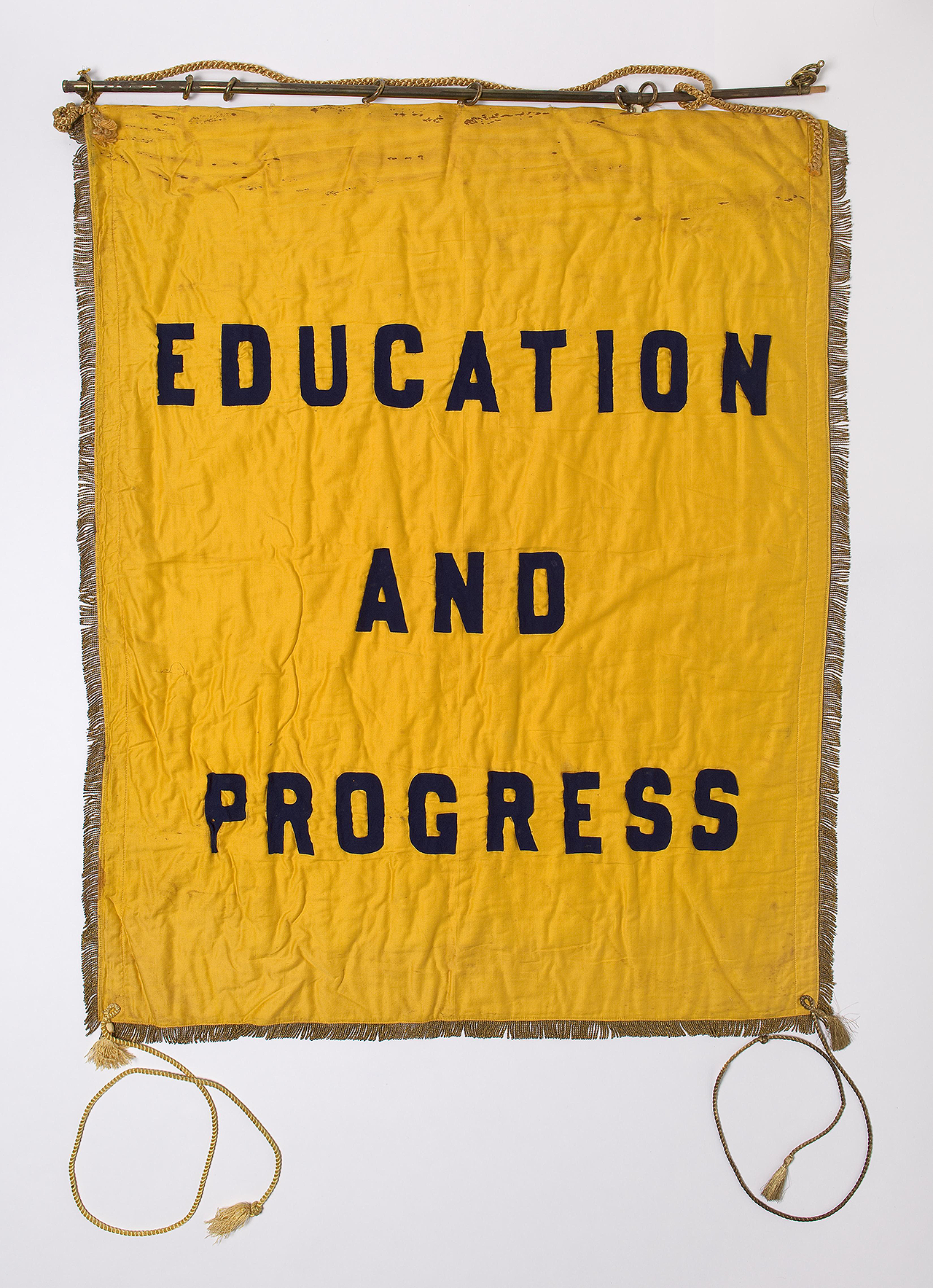

College and university students employed school newspapers to promote the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment as both a war measure and an unavoidable cause during WWI in light of these changes in strategy. Undergraduates wrote pleas for the timeliness and necessity of women’s suffrage that drew on their peers’ progressive impulses and sense of nationalism on Northern campuses. One Radcliffe student wrote late in the campaign, “The Senate seems to have forgotten that we are living in 1918, not in 1908. It is to be expected that a Woman Suffrage Resolution would be defeated 54-30 in 1908, but in 1918, such a vote is behind the times, against the times.”Footnote 94 The same student encouraged her peers to compose letters to politicians explaining their “sentiments” that women’s suffrage was an important contemporary cause that could strengthen democracy and thereby help the nation in the military conflict.Footnote 95 Radcliffe suffragists helped to obtain signatures on a petition to Congress proclaiming Massachusetts’s support for the federal amendment in 1919.Footnote 96 Northern and Western college students conducted initiatives for the constitutional amendment, such as tracking local communities’ political attitudes toward women’s right to vote; writing reports on their findings; and publishing statistics to inform the public, the nation’s leaders, and different activists about the status of the women’s suffrage campaign at the grassroots level.Footnote 97 Other college students seeking ways to contribute to the women’s suffrage cause during the war ramped up existing initiatives to support civic education programs designed to create ideal female voters during the final stage of the women’s suffrage movement.Footnote 98 People began focusing on education and how immigrants and other Americans could be trained for responsible civic participation within the larger culture outside the movement. These trends shaped the women’s rights campaign.Footnote 99 Students and alumni became core allies in these wartime political literacy programs at colleges and universities, using their education and access to academic resources to prepare women on the home front for the duties of responsible, engaged citizenship, fully believing that victory was finally near (fig. 3).Footnote 100

Fig. 3. College Equal Suffrage League banner. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Some university students and alumni in the South also similarly remained active in the women’s suffrage movement, either through CESL-inspired groups or state suffrage organizations, after the national college league disbanded. Tulane was an important site of suffrage activism in New Orleans for both male and female students in the late 1910s. State suffragists frequently allied with local educators and college students to stage events at the university, such as mass meetings, parades, and rallies supporting federal suffrage legislation. These collegiate campaigners remained largely in step with activists in the North or West despite divided local sentiments.Footnote 101 Suffragists in general—including CESL representatives—did face a unique set of challenges when mobilizing for federal enfranchisement in the South. Many Southerners, including Kate Gordon’s followers and others even across classes, had traditionally rejected national legislation granting women the right to vote, viewing women’s suffrage issue as an issue of states’ rights. They advocated against any legal changes that would permit less local control of the government or the electorate. Some white Southerners feared the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment would not only challenge state power but also dismantle white supremacy, a deeply engrained component of society that underpinned many aspects of public and private life.Footnote 102 These attitudes presented a real challenge to organizing the region for equal suffrage at the national level. To counter, some state suffragists and student allies attempted to convince sympathetic and interested parties in their communities that women voters would not undermine the status quo and that seeking a federal amendment would be far more efficient than campaigns for grassroots change in response. They warned that even if national legislation for women’s suffrage passed through Congress, it represented no simple “shortcut to liberty.”Footnote 103 Suffragists would still face the challenge of state ratification, they urged, ultimately leaving the fate of the new national legislation in local hands.Footnote 104

College suffragists’ civic education work, political lobbying, and campus activism were effectively sustained alongside others until congressional approval for the federal legislation and the eventual the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, by Tennessee, the final state needed to legally secure American women the right to vote despite these challenges. By then, three years had passed since the national body of Park’s organization, the CESL, had formally disbanded. But the group’s early goals to promote political literacy among youth and recruit more students and alumni to the women’s rights cause had indelibly altered the culture of higher education and the women’s movement, helping to create a space for it on campus and among youth. The civic clubs, women’s organizations, and college branches of the NAWSA’s legacy groups, like the League of Women Voters (LWV), replaced the CESL in many locations in the period that followed. Park led the LWV’s endeavors, becoming the national president; she had not forgotten the significance of collegiate activism. Even the NWP had a Students’ Council in the years after 1920, recognizing the importance of academic support and the campus as a new stage for the women’s movement.

The CESL’s activism and college campaigns passed through various stages during the early 1900s and, while doing so, cultivated an important training ground for younger generations of women’s rights activists, introducing a previously nonexistent trend of organized advocacy in the academy with acceptance, permanency, and scope. The suffrage movement managed to fit within the culture of academia and progressive reform, largely because of the group’s (and the overarching NAWSA’s) patient, cautious, and educational approach. But at the same time, as the NAWSA and the CESL strove toward greater respectability, the groups did so at a price, driving some campaigners who could have been potential allies and members away. Their seemingly conservative methods and selectivity left some protest spaces and peoples unreached, for example, such as students and faculty at institutions of higher education for African Americans or even more radical young feminists. The CESL and NAWSA suffragists in general, however, by 1920 had succeeded in raising the visibility of their organizing both inside and outside the academy through constructing a more respected and scholarly voice for the campaign, reaching many new audiences, and bringing more college- and university-educated men and women into the movement. Male voters, fellow collegians, and government officials could easily ignore marginal female citizens and their civic platforms, but the growing block of college-educated, upper- and middle-class white Americans rallying behind the cause made it harder to dismiss women’s suffrage in the modern era.