1. Introduction

This research focuses on the verbal expression of gratitude in UK government COVID-19 briefings in 2020–2021. The briefings had many functions, including informing the public of the latest scientific assessments of the disease, communicating a new government policy and persuading the public to come together to follow that policy and other measures to reduce the spread of the disease. Emotional expression was rife in this messaging (Wei, Reference Wei2023b).

As a social emotion, the expression of gratitude has a particular role to play in maintaining authority and achieving persuasion. It increases compliance ‘because people desire connections with others’ (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015, p. 4). Previous research shows that gratitude expressions in political election campaigns increased the likelihood that people would vote in subsequent elections (Panagopoulos, Reference Panagopoulos2011), and a thank-you note from a residential treatment programme to case managers encouraged more frequent visits to their adolescent clients (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Northrop and Barkshire1988). Even a thank you written on the back of customers’ restaurant bills can help servers receive large tips (Rind & Bordia, Reference Rind and Bordia1995).

Based on a corpus-assisted discourse analysis, this research aims to describe how perspective and intensity were mediated in expressing gratitude to realise different pragmatic intentions in UK government COVID-19 briefings. Following this Introduction, Section 2 provides a theoretical background by defining gratitude, explaining the functions and perspectives of gratitude expression and describing its dynamics. Section 3 introduces the data collection and the discourse analytic method. Section 4 describes the corpus-assisted analysis conducted to interpret English gratitude expressions and group their patterns. Section 5 discusses the dynamic pattern of linguistic expression of gratitude in terms of perspective, intensity and effect. Section 6 concludes the research with its main findings and future research suggestions.

2. Theoretical background on gratitude and its dynamic expression

2.1. What is gratitude?

Gratitude is ‘a crucial ingredient of every society and culture’ (Komter, Reference Komter, Emmons and McCullough2004, p. 208). It is defined as the recognition and appreciation of an altruistic gift (Emmons & McCullough, Reference Emmons and McCullough2004). As a personal asset, it is ‘a means of establishing social cohesion and creating a shared culture’ (Komter, Reference Komter, Emmons and McCullough2004, p. 208). It can help us get through difficult times and flourish in good times by promoting our relationship with those who are responsive to our likes and dislikes, and needs and preferences (Algoe et al., Reference Algoe, Haidt and Gable2008).

Gratitude involves a giver (benefactor) and a receiver (beneficiary). It is a positive emotion expressed for ‘kindness, generousness, gifts, the beauty of giving and receiving, or getting something for nothing’ (Pruyser, Reference Pruyser1976, p. 69). According to Wierzbicka (Reference Wierzbicka1999), gratitude can be understood as having three components:

-

a. someone has done something good for me;

-

b. this person didn’t have to do it;

-

c. I don’t necessarily want to reciprocate, but at least I want to think good things about my benefactor.

This shows that a benefit has a ‘gratuitous nature’ (Wierzbicka, Reference Wierzbicka1999, p. 105), and it may elicit in the beneficiary good thoughts about the benefactor or willingness to ‘repay the favours’ (Wierzbicka, Reference Wierzbicka1999, p. 105). By looking to help the benefactor, showing ‘a certain concern for the well-being’ of the benefactor or trying to ‘return a benefit’ (Naar, Reference Naar, Roberts and Telech2019, p. 21), a grateful person expresses the recognition of a benefit and creates and maintains social bonds and relationships (Algoe, Reference Algoe2012).

Gratitude can be expressed in three ways: verbal gratitude, concrete gratitude (reciprocating with a physical gift or an action) and connective gratitude (reciprocating with something like friendship or help). Verbal gratitude is particularly flexible in that it varies in quality, frequency, intensity, perspective, etc. It can be expressed by different linguistic resources in order to highlight different aspects of a thanking act. For instance, thank you for your patience can accentuate its performative aspect; a thank you to everybody can accentuate its expressive aspect; and be grateful to everyone can accentuate its descriptive one. Verbal gratitude can be displayed by acknowledging ‘self-benefiting’ (how much a beneficiary has profited from a benefit) or doing ‘other-praising’ (praising how much a benefactor has done for a benefit) (Algoe et al., Reference Algoe, Kurtz and Hilaire2016; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Burgmer and Lange2020). Therefore, verbal gratitude is often studied in different communicative contexts by linguists (e.g. Eisenstein & Bodman, Reference Eisenstein and Bodman1986; Gkouma et al., Reference Gkouma, Andria and Bella2023; Hymes, Reference Hymes and Ardener1971; Wong, Reference Wong2010; and this paper) and psychological researchers (Armenta et al., Reference Armenta, Fritz and Lyubomirsky2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhu, Guo and Liu2023; Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015).

2.2. Gratitude expression: functions and perspectives

Emotions are ‘about’ something: they involve a direction or orientation towards an object (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson1995, p. 8). Emotional expression is ‘intentional’ (Archer, Reference Archer2000, p. 4). It can express ‘what’s inside’, direct ‘other people’s behaviour’, represent ‘what the world is like’ and commit ‘to future courses of action’ (Scarantino, Reference Scarantino2017, p. 165). In other words, emotions involve a stance on the world or a way of apprehending the world (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014, p. 7). They are triggered by personal evaluations, which in turn are represented by emotions; thus, emotional expression is an expressive act as well as a commissive one. When one expresses an emotion, one is responsible for changing the world (i.e. ‘prioritising the pursuit of one goal at the expense of others’ or ‘surrendering one’s control over one’s future behaviour’; Scarantino, Reference Scarantino2017, p. 180) in order to satisfy the conditions for the emotional expression.

As a moral emotion, gratitude is expressed to declare ‘readiness to encourage or support’ a beneficial action (as opposed to readiness to appease or attack; Scarantino, Reference Scarantino2017, p. 180). It facilitates successful social relationships by providing people with the incentives to engage in social interactions and increases the likelihood that people will adhere to social norms that are necessary for group living. With its powerful moral, psychological and social functions, gratitude has been labelled as ‘the greatest of the virtues’, ‘the parent of all others’ (Cicero, Reference Cicero1851, p. 139) and ‘the moral memory of mankind’ (Simmel, Reference Simmel1950, p. 388).

A gratitude expression can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective thanking, that is ‘thanking’ as a type of illocutionary act, has been defined by Searle (Reference Searle1969, p. 67) as a grateful or appreciative speech act based on past beneficial acts performed by the hearer. It is expressed ‘after the fact’ (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015) to recognise the favours of benefactors and encourage their continued contributions. On the other hand, thanking with prospective timing typically occurs within or following a request (De Felice & Murphy, Reference De Felice and MurphyForthcoming). It is adopted when a benefit is being given or expected to be given by the benefactor(s). It is conveyed ‘before the fact’ (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015) or for the current fact to introduce a persuasive request or a polite reminder (e.g. thank you for wearing a face covering; cf. Wei, Reference Wei2023a, p. 14) in order to mitigate the imposition on the favour-givers and strategically realise negative politeness.

2.3. Dynamics of gratitude expression

Emotional concepts can be represented as cognitive-cultural models in the mind (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2014, p. 15). In Kövecses’ prototypical cognitive-cultural model of emotion expression, a situation and an emotion form a force-dynamic pattern (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2014, p. 23). A situation is conceived of ‘as a forceful entity’ in eliciting emotion (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2014, p. 23). Emotion is not only the result of a particular situation/force but also the trigger of some actions (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2014, p. 23). For instance, happiness or joy is elicited by ‘a situation in which you wanted something to be the case and now it is the case’ (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses1991, p. 34). In the meantime, a happy or joyful person may find some way (facial, postural or verbal) to display his/her emotion. In other words, both emotional experience and expression can be examined in terms of force dynamics.

With regard to gratitude, what enters the force-dynamic pattern is the situation where gratitude is elicited (i.e. what benefit has been given) and the gratitude expressed by a speaker. The situation is the force of arousing grateful feeling. The evoked gratefulness may lead to physiological responses and/or linguistic expressions.

Gratitude is elicited by the expresser’s evaluation of the benefit(s) and the benefactor’s social identity or influence. Linguistic expressions of gratitude demonstrate the expresser’s stance in evaluating a benefit and the relationship between the beneficiary (usually the expresser) and the benefactor(s). In this way, the expresser can direct or elicit a response from the benefactor(s) or redefine their relationship. For instance, by using A is grateful to B who has done …, a speaker/writer can express retrospective thankfulness and display their appreciative or supportive stance on the benefit; by using pay a huge tribute to…, a speaker/writer can construct the respectable identity of the benefactor(s) and convey retrospective gratitude formally and intensely; by using thank you for doing…, a speaker/writer can express prospective thanking and implicitly direct the benefactor (or the audience) to make a change or continue a certain action; and by using a big thank you to B, a speaker/writer can orient recognition and appreciation towards the benefactor(s) and intensify their affective stance.

Naar (Reference Naar, Roberts and Telech2019) differentiates generic gratitude from deep gratitude. Generic gratitude is ‘a particular mode of recognition of the impact other people have on one’s life and of the quality of their character’ (Naar, Reference Naar, Roberts and Telech2019, p. 21). It is a consequence of holding the beliefs that a benefit was given by the benefactor out of benevolent attitudes and that the recipient had benefited from it. For instance, generic gratitude is expressed to a person who is holding a door for us when we are going to enter it. Deep gratitude is triggered not only by the beliefs about the benefactor and the benefit received but also by the affinity between the benefit (or some aspect of the benefit) and one’s cares, desires and likes. If a benefit is what the recipient needs, deep gratitude may be displayed. For instance, lending or sharing an umbrella on a rainy day may be a benefit to a person who has to travel in the rain without rain gear, and deep appreciation may be expressed to the benefactor who is trying to give the timely help.

The dynamic relationship between a situation (e.g. a benefit) and gratitude can be represented by different linguistic patterns. When a benefit is large or larger than usual, deep or heightened gratitude may be expressed by (say) a big/massive thank you, be profoundly grateful or pay a huge tribute. If a benefit is enacted by an individual, a group or an institution that is deemed as not obliged to make any effort for it, stronger expressions of gratitude are usually targeted towards them. When this benefit is given beyond the beneficiary’s expectation, heightened gratitude tends to be expressed by praising what the benefactor has done for it (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Burgmer and Lange2020, p. 1616).

Gratitude expression is related to social norms, conforming to the principles of ‘appropriateness’ and ‘genuineness’ (Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2014, p. 23) and observing the ‘display rules’ (Matsumoto et al., Reference Matsumoto, Yoo, Fontaine and Friedlmeier2008) that dictate which response (‘amplify, de-amplify, mask, or neutralise’; Matsumoto et al., Reference Matsumoto, Yoo, Fontaine and Friedlmeier2008, p. 65) is socially and culturally acceptable in which situation. While gratitude expression facilitates compliance (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015) or pro-sociality (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Tunney and Ferguson2017), it can inhibit ‘compliance because people desire personal freedom’ and even induce repugnance or hatred (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2015, p. 6). Therefore, it is necessary for speakers to mediate the expression of gratitude in social interaction and discourse.

We return to these issues in Section 4 in analysing the expression of gratitude in UK government COVID-19 briefings.

3. Data collection and methodology

With the support of Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al., Reference Kilgarriff, Rychlý, Smrž and Tugwell2004, Reference Kilgarriff, Baisa, Bušta, Jakubíček, Kovář, Michelfeit, Rychlý and Suchomel2014; http://www.sketchengine.eu), two corpora were built, from the UK government COVID-19 briefings as part of a larger project examining emotionality in COVID-19 briefings (Wei, Reference Wei2023b).

3.1. Data collection

During the pandemic, the UK government implemented three lockdowns (restricting access to public space and limiting people’s movement) from 23 March 2020 to 19 July 2021. At different stages of the national campaign against COVID-19, the government strove to guide people to stay at home (or self-isolate), to take certain protective measures (wash hands thoroughly, observe social distancing, wear face masks) or to get vaccinated in order to contain the virus within the community. To communicate with the public directly and clearly, the Office of the Prime Minister (No. 10 Downing Street) held daily briefings, which were broadcast live on BBC television and YouTube during the three national lockdowns.

In total, 18 politicians and 21 medical experts engaged in 156 government briefings. The main politicians included Prime Minister Boris Johnson and members of his cabinet: Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak and Transport Secretary Grant Shapps; the experts’ group was represented by Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance, Chief Medical Officer Professor Chris Whitty, National Medical Director of National Health Service (NHS) England Professor Steve Powis, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Professor Jonathan Van-Tam and Dr Jenny Harries.

Corpus compilation followed three steps. First, transcripts of the speeches of the Prime Minister and cabinet members were gleaned directly from the official website of Public Health England. Other speeches were automatically transcribed by Microsoft Office 365 Word from the videos on the website. All of the transcripts were then proofread verbatim against the corresponding videos on their YouTube channel. Because our research focuses on semantic and syntactic features of the speeches, prosodic features (e.g. pause, pitch and speed) were not marked in the corpora. Finally, two Word documents, one for politicians and the other for medical experts, were uploaded to Sketch Engine for automatic annotation and compilation.

Details of the English COVID-19 briefing corpora are presented in Table 1. In the Politicians’ Corpus, there are 168 texts because some daily briefings included two politicians’ speeches, while in the Experts’ Corpus, there are 153 texts because experts were absent from some briefings.

Table 1. Details of English COVID-19 briefing corpora

3.2. Corpus-assisted discourse analysis

Adopting a corpus-assisted method, this research analyses the gratitude expressions in the two corpora. In English, gratitude is usually expressed by verbs such as thank and appreciate, adjectives like grateful and nouns like gratitude. Therefore, as the first step, six words (thank, grateful, tribute, owe, appreciate and gratitude) were chosen as search terms for frequency count.

Then collocates and concordance lines of the highly frequent gratitude terms were examined in order to discover their salient constructions present in both corpora and unveil the context where the dynamic expression of gratitude was mediated by the two elite groups for persuasive communication. Finally, linguistic patterns of the thanking act were generalised, and the two corpora were searched for these constructions.

4. Corpus-assisted analysis of gratitude expressions

This section presents a fine-grained analysis of gratitude expressions in the two corpora in terms of frequency, collocation and concordance.

4.1. Frequencies of potential gratitude expressions

Thank, grateful, tribute, owe, appreciate and gratitude were chosen as search terms for frequency count in order to show how gratitude was expressed by the two groups of speakers in the public discourse.

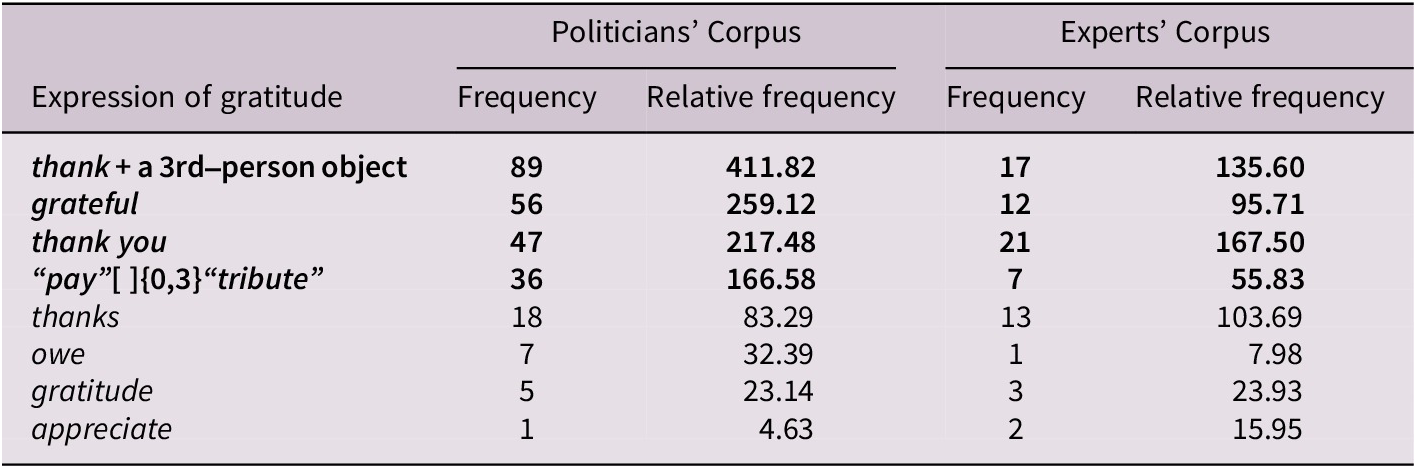

Thank is often used with you to express gratitude in social interaction and discourse. But as Hymes (Reference Hymes and Ardener1971, p. 69) points out, in British English, thank you ‘seems on its way to marking formally the segments of certain interactions, with only residual attachment to “thanking”’ (p. 69). Rubin (Reference Rubin1983) also discovers that thank you can signal the conclusion of a conversation, as well as expressing gratitude and compliments. In government briefings, thank you was used for this kind of ritual politeness at the beginning or end of a speech. Excluding these occurrences, we counted the frequencies of thank you in the two corpora. As Table 2 shows, thank you has 47 and 21 instances in the Politicians’ Corpus and the Experts’ Corpus, respectively. It is the most frequent gratitude expression in the Experts’ Corpus, while it is the third most frequent one in the Politicians’ Corpus.

Table 2. Frequencies of gratitude expressions in the Corpora

In the Politicians’ Corpus, the most frequent gratitude expression is thank with a third-person object. This pattern occurs 89 and 17 times in the Politicians’ Corpus and the Experts’ Corpus, respectively. In addition, the adjective grateful and the pattern “pay” [ ]{0,3} “tribute” (with up to three intervening words) enjoy higher frequency in both corpora.

In terms of relative frequency (frequency per million words), both thank + a third-person object and “pay” [ ]{0,3} “tribute” are used in the Politicians’ Corpus about three times as frequently as in the Experts’ Corpus. However, thank you has only a little higher frequency in the Politicians’ Corpus than in the Experts’ Corpus.

In brief, among the eight expressions of gratitude, thank you, thank + a third-person object and grateful (highlighted in bold) occur more in both corpora. Although “pay” [ ]{0,3} “tribute” (highlighted in bold) has a lower frequency than thanks in the Experts’ Corpus, it is used far more frequently than thanks in the Politicians’ Corpus.

4.2. Collocation and concordance of key gratitude expressions

In this section, the highly frequent gratitude expressions are interpreted in terms of collocation and concordance.

4.2.1. Thank you (or a third-person object)

Thank you is used in the corpora as a verb phrase, a compound noun or an interjection (discourse marker). As is shown in (1a), it is used as a verb phrase to highlight the performative aspect of thanking act and express action-oriented gratitude. It can also be used to demonstrate the expressive aspect of thanking act and express speech-oriented gratitude, as illustrated in (1b), (1c) and (1d).

In (1b), to say a big thank you is employed to emphasise the act of thanking a third party verbally and explicitly in communication with the general public. In (1c), the verb say is left out and a noun phrase that includes thank you and its adjective modifier huge is used to convey gratitude to the speaker’s friends and colleagues in the NHS. In (1d), only thank you is utilised as a quote to express thankfulness to the general public who observed the guidance.

As is seen in (1b), (1c) and (1d), thank you enables the speakers to express speech-oriented gratitude directly to the third party or indirectly to the audience. It facilitates socially inclusive behaviours, which sometimes require a personal cost to oneself (Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Condon, Cruz, Baumann and Desteno2012).

This speech-oriented usage has 25 occurrences (accounting for 53% of thank you’s uses for gratitude) in the Politicians’ Corpus and helps the politicians connect as many benefactors as possible.

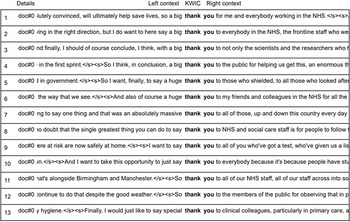

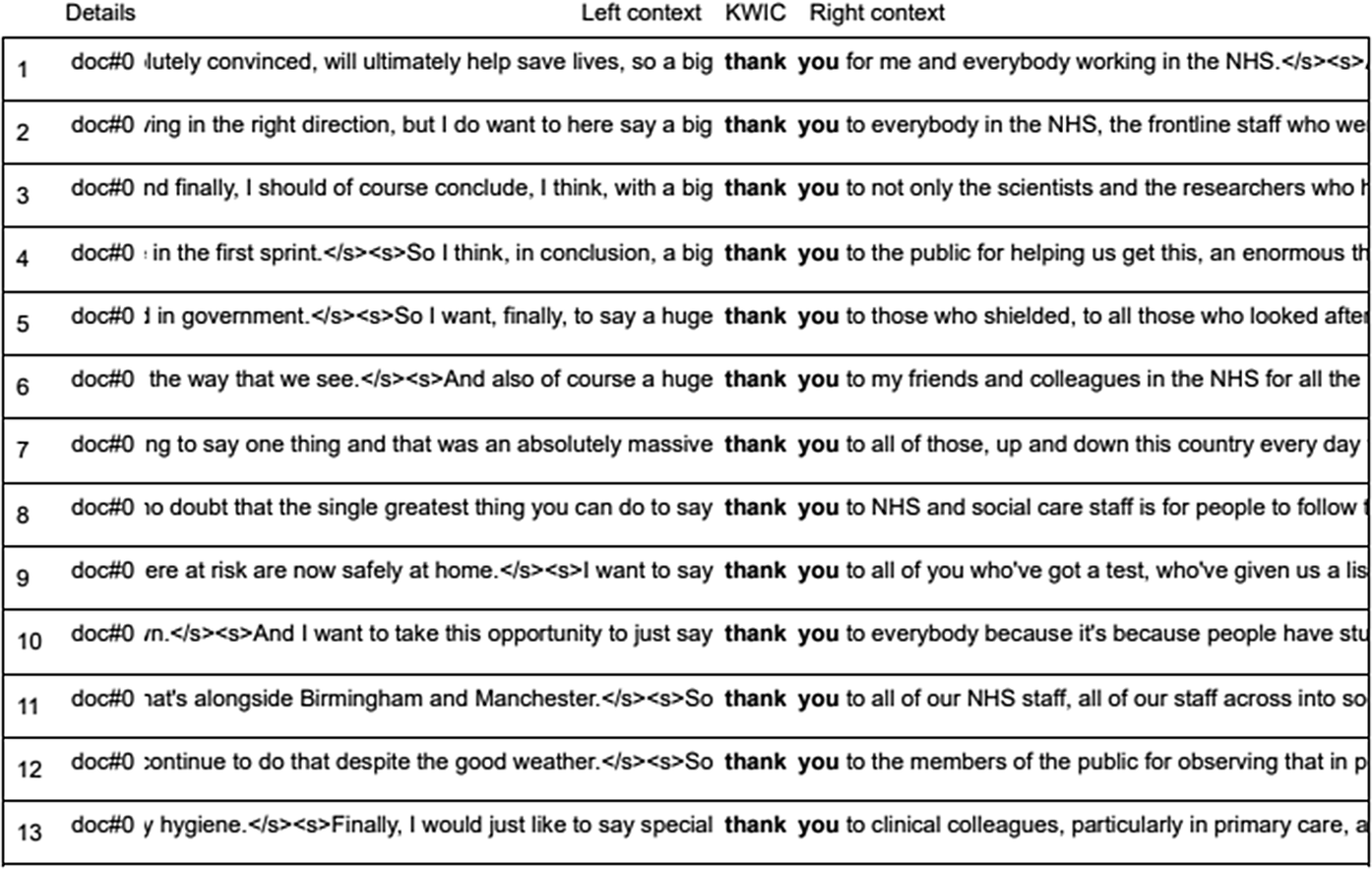

Figure 1 shows gratitude was expressed by the politicians towards everybody who did their bit in protecting lives in the UK: NHS staff, carers, key workers, volunteers, educational workers, as well as the general public who followed the government guidance to stay at home or get vaccinated.

Figure 1. Concordance of thank you in the Politicians’ Corpus.

In the Experts’ Corpus, there are 13 cases of expressive thank you (accounting for 51% of its uses for gratitude) and you, the benefactors defined here, according to Figure 2, refers to NHS staff, unsung scientists, social care staff, volunteers who were working to protect people and the general public who were following the government’s guidance.

Figure 2. Concordance of thank you in the Experts’ Corpus.

Concerning the expressive use of thank you, both sets of speakers used adjective modifiers. Among the eleven intensified occurrences of thank you in the Politicians’ Corpus, five different adjectives are exploited, while three adjectives appear in its seven cases in the Experts’ Corpus. As Table 3 shows, the three adjective modifiers massive, huge and big (highlighted in bold) occur in both corpora. They all point to the amplification of verbal gratitude and reflect a parameter of gratitude intensity: metaphorical size (scale).

Table 3. Adjective intensifiers of thank you in the Corpora

In the Politicians’ Corpus, intensified gratitude marked by the construction a(n) + adj + thank you is intended to target mainly the cooperative general public, while in the Experts’ Corpus, the target benefactor is every individual who complied with the public health guidance or who was working in the NHS, including frontline workers, researchers and scientists.

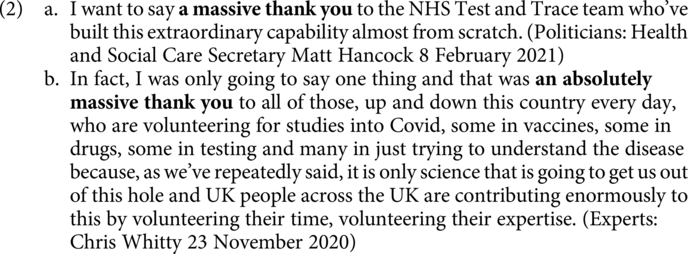

In (2), a(n) (…) massive thank you is used to express thankfulness to the NHS Test and Trace team for their great work or to the volunteers for their brave participation in COVID-19-related experiments for protecting public health.

As a verb, thank can take other objects than you in order to explicitly mention the benefactor(s). As Figure 3 shows, everyone and everybody appear as the objects of thank more frequently than staff in both corpora. This suggests that the politicians and the medical experts tended to uniformly express thankfulness towards every individual in the general public and/or in a specific team (e.g. NHS or volunteering team) throughout the three national lockdowns.

Figure 3. Objects of thank in the Corpora.

While staff, team, parent and business represent the benefactors to whom gratitude is expressed in the Politicians’ Corpus, colleagues, people and staff are viewed as the objects of gratitude in the Experts’ Corpus.

4.2.2. Be grateful

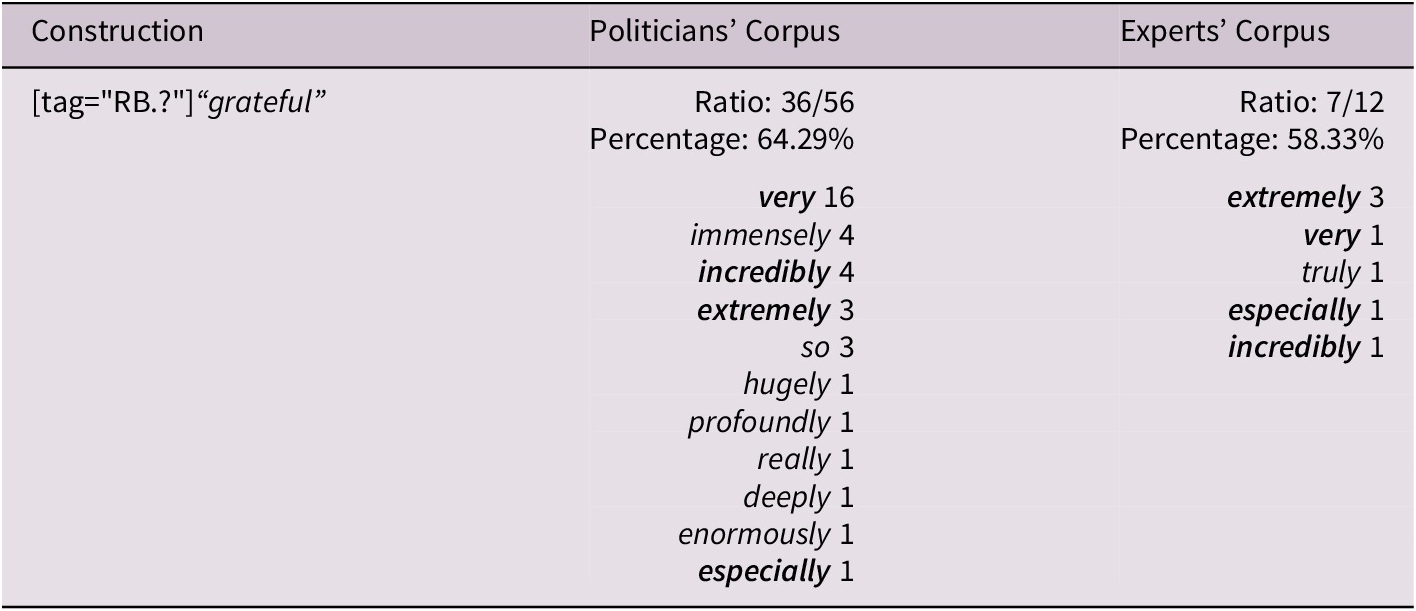

Grateful is another frequent expression of gratitude in the corpora. It takes adverb modifiers at about 64% (36 out of 56 cases) in the Politicians’ Corpus and roughly 58% (7 out of 12 instances) in the Experts’ Corpus. As Table 4 shows, the four adverbs shared in both corpora are very, incredibly, extremely and especially (shown in bold in Table 4). These intensifiers involve four parameters of gratitude intensity: degree, common sense, extreme value and typicality.

Table 4. Intensifiers of grateful with their frequencies in the Corpora

Incredibly is one of the amplifiers used in both corpora. In (3a), intensified gratitude is expressed to all members of staff in the NHS and volunteers. The pandemic ruthlessly pushed NHS staff to the frontline. These frontline workers and volunteering people were defined as the target group of the gratitude expression by the politician on behalf of the beneficiaries. In this example, gratitude is expressed through the pattern be grateful to sb. who-clause to describe the beneficiary’s grateful feeling and praise the benefactor’s efforts for the benefit. In (3b), the expert passes on his NHS colleagues’ heightened appreciation for the public’s incredible cooperation and acclaim over the past year.

Especially is another booster of gratitude in both corpora. In (4a), the benefactor being thanked is the Royal British Legion and those hard workers; in (4b), the benefactor who deserves the gratitude is everybody who was involved in COVID-19 testing in Liverpool. With the help of the adverb especially, the speakers could strengthen their gratefulness as well as the benefits the benefactors provided for protecting public health. In (4a) and (4b), the same pattern is adopted for gratitude expression, albeit the use of different tenses in who-clause. In (4a), the simple past is used, whereas in (4b), the present perfect is employed. The difference in tense choice points to the benefit’s difference in duration and magnitude.

Extremely is the third amplifier found in both corpora. As is shown in (5), strong gratitude is expressed to teachers in (5a) and to soldiers in (5b) for their contribution (risking their lives in doing their duties) to education or community safety during the pandemic. In (5a), gratitude is expressed by the pattern be grateful to sb. for sth., while in (5b), the gratitude expression is be grateful for sth. because-clause. The first pattern appears to express gratitude to the benefactor more directly and briefly than the second one. However, the second one allows the mention of the benefit and the reason for the speaker’s appreciation.

The use of the three amplifiers (incredibly, especially and extremely) in both corpora demonstrates that both politicians and experts adjusted their expression of gratefulness in the public discourse when the benefits met their expectations and/or the benefits were great.

In the Politicians’ Corpus, seven more intensifiers occur. These modifiers reflect that intensified gratitude is expressed by highlighting the degree (e.g. so), describing the metaphorical dimensions (WIDTH: immensely, enormously, hugely; DEPTH: deeply and profoundly) of gratitude or, in one case, showing sincerity (e.g. really). In the Experts’ Corpus, most intensifiers relate to degree, but sincere gratitude is highlighted once by the adverb truly. These twelve adverbs were adopted as gratitude boosters to demonstrate speakers’ nuanced gratefulness and personal distinctive evaluations about the issues in question.

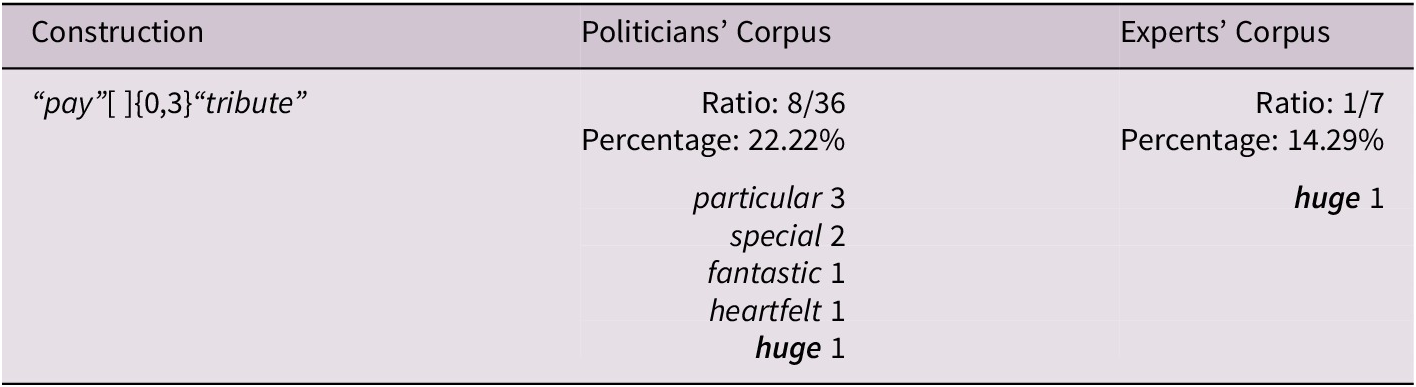

4.2.3. Pay (a…) tribute

Unlike thank you (or sb. else) and be grateful, pay (a…) tribute alludes to the respectability and superiority of the target benefactor. It is more frequently used in the Politicians’ Corpus than in the Experts’ Corpus. It collocates with some adjective modifiers to heighten the expression of gratitude. It has about 22% and 14% of uses with modifiers, respectively, in the Politicians’ Corpus and the Experts’ Corpus. As Table 5 shows, huge appears as the modifier of tribute in both corpora. This suggests that tribute is viewed as a tangible object and its intensity is reified into the big size of an object. In addition, the Politicians’ Corpus includes more adjective modifiers of tribute. They are used to describe the features (e.g. intensity and sincerity) of tribute in order to strengthen the expression of gratitude.

Table 5. Intensifiers of tribute in the Corpora

The two examples in (6) depict situations in which heightened gratitude was expressed by the politician and the expert. In (6a), the politician’s target benefactors include a broad range of people in roles related to shielding the vulnerable, while in (6b), the expert expresses intensified gratitude to all NHS staff. Tribute acknowledges that these benefactors made particularly great sacrifices, which earned them special respect and gratitude from the politician and the expert.

4.3. Linguistic patterns of thanking act

Having interpreted the collocates and concordance lines of the three key gratitude expressions in both corpora, we can generalise the thanking patterns by using thank, thank you or grateful to demonstrate the performative, expressive and descriptive aspects of thanking act respectively:

Thank (performative):

(1a) A thanks B for sth./doing sth.

(1b) A thanks B who did/has done….

(1c) A thanks B who does/is doing….

(1d) A thanks B who is going to do/will do….

Thank you (expressive):

(2a) thank you to sb. for sth./doing sth.

(2b) thank you to sb. who did/has done…

(2c) thank you to sb. who does/is doing…

(2d) thank you to sb. who is going to do/will do…

Grateful (descriptive):

(3a) A is grateful to B for sth./doing sth.

(3b) A is grateful to B who did/has done…

(3c) A is grateful to B who does/is doing…

(3d) A is grateful to B who is going to do/will do…

These patterns demonstrate the perspective from which gratitude was expressed in government briefings. In them, A stands for the recipient of a benefit, while B is the person who gives/is giving/will give the benefit(s) to the beneficiary.

As Table 6 shows, Pattern 1, the performative pattern of thank, is the dominant one in both corpora. It has four variants, with Pattern (1a) (highlighted in bold) having the highest frequencies and Pattern (1b) enjoying a similar popularity as Pattern (1a) in both corpora. Patterns (1c) and (1d) have fewer cases, but they can be used to express prospective thanking together with Pattern (1a).

Table 6. Frequencies of gratitude expression patterns in the Corpora

Among the thank you patterns, Pattern (2b) (highlighted in bold) has the most occurrences in both corpora. It was adopted to express retrospective gratitude. In contrast, Patterns (2a) and (2c) were involved in prospective thanking.

Regarding the grateful patterns, Pattern (3a) (highlighted in bold) is a little more frequent than Pattern (3b) in the Politicians’ Corpus, though it has the same cases as (3b) in the Experts’ Corpus. Contrary to Pattern (3b), it was employed for prospective thanking, together with Patterns (3c) and (3d) in the public discourse.

While these patterns reflect how gratitude was expressed for acknowledging or directing in the public discourse, they do not unveil the interaction between the types of the benefits given by the benefactors and the variables (e.g. intensity or sincerity) of gratitude expressed by the beneficiaries. In order to better understand how gratitude expression is mediated in the public discourse, we need to concentrate on the use of intensifiers, including the adjective and adverb modifiers, in these thanking patterns. Moreover, we have to consider more contextual factors (e.g. the beneficiary’s likes or needs, the potential favour-giver’s identity or responsibility) to hypothesise the dynamic process of gratitude expression.

5. Discussion

In UK government COVID-19 briefings, gratitude was expressed to build solidarity and/or make requests. In the public discourse, thanking act, retrospective or prospective, serves double social functions: facilitating compliance with the government guidance and interfering with disobedience with the advice. Framing gratitude expression as retrospective or prospective, both politicians and experts intended to achieve gratitude of exchange; that is, the object of gratitude (e.g. the audience) would be inspired and try to reciprocate (e.g. start or continue complying with the government guidance) the expresser (usually the beneficiary) directly and actively as expected. In almost all of the cases of gratitude expression in the briefings, benefactors’ efforts or contributions were mentioned to illustrate the speakers’ expectations. In this sense, gratitude expression is deemed as more of a commissive act than an expressive one.

In expressing gratitude, perspectives and intensity were mediated by politicians and epistemologists to encourage or direct a beneficial action for public health.

Retrospective thanking and prospective thanking are present in the public discourse, with politicians expressing gratitude more frequently in either perspective than experts. Politicians and experts both adopted prospective thanking more frequently than retrospective thanking. By acknowledging the benefactors’ favours, sacrifices or contributions, politicians and experts aimed to encourage them (e.g. the general public) to keep cooperating with the government in stopping the spread of the virus and protecting lives in the UK. By describing the potential benefits in different tenses: simple present, present progressive, simple future and future progressive, they strategically mediated their expression of prospective thanking for making requests or reminders.

In addition, gratitude of varying intensities was expressed to align with the received benefits and the benefactor’s identity (or responsibility). In retrospective thanking, gratitude was intensified to highlight the benefits or benefactors by employing pre-posed adjective and adverbial modifiers (e.g. huge, big, massive, immensely, deeply or extremely). These amplifiers demonstrate five parameters (size, width, depth, degree and sincerity) of gratitude intensity and unveil how this emotion was conceptualised metaphorically. In this thanking act, gratitude was conceptualised as a tangible entity and its expression was intensified by specifying the dimensions of thank you or tribute or by describing the grateful feeling metaphorically (e.g. immensely/profoundly grateful) as a two-dimensional object.

Based on the corpus-assisted analysis of the politicians’ and experts’ gratitude expression in UK government COVID-19 briefings, a preliminary model can be formulated to describe the dynamic process of gratitude expression for encouraging or directing effects (see Figure 4) in public discourse.

Figure 4. Dynamics of gratitude expression in public discourse.

A grateful experience usually goes before gratitude expression. This emotional experience is more of a cognitive evaluation. A benefit (major or minor, tangible or intangible) may be evaluated in relation to the beneficiary’s preference or expectation as well as the benefactor’s identity and responsibility. It may evoke intensified gratitude if it well matches the beneficiary’s likes or needs. The same benefit, given by two people, a relative and a stranger, may elicit gratitude of different intensities. Moreover, if a benefit is defined as not falling into a benefactor’s responsibility or being given at a certain peril or expense, stronger gratitude may be elicited and expressed. This reflects the dynamics between gratitude expression and its cause (e.g. the given or expected benefit). Gratitude sincerity and intensity vary with benefit importance and the benefactor’s degree of involvement in this giving act.

Gratitude expression needs regulating. Its regulation involves matching its social effects with its expression perspectives and exploring gratitude dimensions. On the one hand, prospective thanking is chosen to direct the future actions of the target benefactors and show the speakers’ grateful commitment to the potential benefits. In prospective thanking, generic gratitude is displayed for the benefits (normally minor) without extending the emotional dimensions or reifying the emotional language.

On the other hand, retrospective thanking is used to not only acknowledge and encourage the major benefits of the benefactors but also strengthen the speakers’ social relationship by sharing their concern and care for the benefactors. In retrospective thanking, deep gratitude may be triggered by the major benefits and conveyed in the patterns, which demonstrate the tangibility of the verbal gratitude or represent metaphorically its dimensions such as SIZE, WIDTH and DEPTH. For instance, pay a huge tribute fits the high-profiled expression of retrospective gratitude for big tangible benefits, and immensely grateful or a big thank you is likely to realise the expression of heightened thankfulness.

Thanking act has performative, expressive or descriptive aspects. Different linguistic expressions can be adopted to do the speech act, express the emotion or describe the beneficiary’s gratefulness. In the public discourse, (a…) thank you was frequently used for the expressive and intensified thanking act.

6. Conclusion

This research has shown that gratitude, like other emotions (cf. Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980), is conceptualised as an entity with size (immensely grateful or a big thank you) or depth (deeply or profoundly grateful). In this sense, it has contributed to the study of the metaphoric structure of emotions (cf. Kövecses, Reference Kövecses2010). In addition, it has presented a variety of linguistic resources to express thanking (retrospectively or prospectively, strongly or not) strategically for solidarity and/or compliance.

It has also explored the potential of gratitude as a social lubricant that ‘acknowledges mutual civility and build trust’ between the benefactor and the beneficiary in public discourse (Buck Reference Buck, Emmons and McCullough2004, p. 111). Furthermore, it has illustrated the great value and practical application of English gratitude expression as an emotional strategy for making a request or reminder in public health discourse (cf. Wei, Reference Wei2023a). Relevant research shows that tailored messages contribute to improving trust and public health uptake (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Moravec, Kim and Dennis2021; Murthy et al., Reference Murthy, LeBlanc, Vagi and Avchen2020; Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2023; Slavik et al., Reference Slavik, Darlington, Buttle, Sturrock and Yiannakoulias2021) and that messages in risk communication should be transparent, evidence-based and action-oriented (Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2023).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, guidelines should be delivered in a bottom-up mode in order to create solidarity and encourage protective behaviours (Porat et al., Reference Porat, Nyrup, Calvo, Paudyal and Ford2020). According to Ogiermann & Bella (Reference Ogiermann and Bella2023, p. 344), Prime Minister Boris Johnson used 33 directive forms in his two speeches (of 16 and 23 March 2020) to request people to take cooperative actions in the national campaign. Their research shows that Johnson employed top-down communication to direct public compliance at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. This research, supported by more data, has found that British politicians and epidemiologists could adopt the bottom-up communicative approach and exploit the directive and persuasive values of gratitude expression in uniting any possible favour-giver, the general public in particular, and facilitating specific cooperation and voluntary compliance. In brief, it demonstrates the power of gratitude expression in boosting social cohesion and directing social actions in a discourse of crisis.

Most importantly, it has constructed a model of gratitude expression in an interactional perspective and revealed speakers’ subjective initiative in adopting gratitude expressions for social or moral functions. This tentative model and a new perspective are conducive to analysing the dynamics of gratitude expression in English public discourse.

This research has examined the dynamics of two elite groups’ gratitude expressions in a specific genre of English discourse (to be exact, public discourse of crisis). Given the small size of the corpora and the limited types of speakers, future research can consider including more genres of English discourse in order to reflect the universality of the metaphorical conceptualisation of gratitude and delve into the power of gratitude expression in building solidarity and directing social actions in a wider cultural context. Moreover, it is necessary to conduct a longitudinal study of all politicians’ or just the Prime Minister’s use of gratitude strategy for persuasion and direction in the government COVID-19 briefings. It is also advisable to study how the English gratitude expressions extracted in this research are perceived by the public and whether they contribute to facilitating public health compliance or not. Such methods as experiments, testing and interviews may be introduced to confirm or supplement the current research and highlight the dynamics of English gratitude expression more effectively.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.