Introduction

Looking with retrospect from the 2020s, the previous decade seems to have been suspended between two major crises: the Great Recession at its beginning, and the Covid-19 pandemic at its end. However, those 10 years did not pass smoothly while awaiting something that citizens could not yet foresee, and especially so in South-European countries.

While the economic crisis was more swiftly overcome in other parts of the continent, in Southern Europe it continued for most of the decade. The Gross Domestic Product of the area returned to pre-crisis levels only in 2016, while it was already between 20% and 30% above that reference point in other parts of Europe. The labour market situation in Southern Europe was even worse, with employment levels in 2019 still lower than those before 2008, while all the other European regions had experienced an up to 10% increase in the number of employed persons.

The economy was not the only concern of the 2010s. The European migrant crisis hit midway through the decade. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, sea and land arrivals in the Mediterranean area peaked at more than one million persons in 2015, but continued at a sustained level also in the subsequent period (UNHCR 2021: 1500). Southern Europe was the forefront of those flows, although the final destinations for many refugees were other countries in Central and Northern Europe. Only in 2019 did the responsible EU Commissioner declare the crisis to be over, although he suspected that ‘migration will continue to be an important topic, and [that] will feature prominently in many election campaigns across Europe’ (EU Commission, 2019).

The uniquely complex situation experienced by the South-European region justifies the scope conditions of our research, which investigated the electoral consequences of the economic situation and foreign presence. The overall area is a good example of extreme, if not extraordinary, conditions in which to test our hypotheses. At the same time, the four nations on which we focused our analysis – Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain – display some interesting cross-country variation, which was further magnified by comparison among subnational units, whose economic performance and immigration levels and trends were even more varied.

Our results confirmed some association between the state of the economy and immigration levels, on the one hand, and the average electoral punishment of the incumbent government on the other, while also highlighting some interesting conditional patterns related to the complex relationship between the two dimensions, and to the partisanship of the incumbents.

The article is organised as follows. The next section introduces the context in which South-European citizens were called to the ballot boxes in the 2010–2019 period. Section three discusses the theoretical framework, and more specifically the possibility of adapting a retrospective perspective to both the economic and immigration dimensions. Section four illustrates the methodology adopted and the variables used, focussing on the approach based on within-country data collected at the level of NUTS3 territorial units.Footnote 1 Section five illustrates the empirical results of the analysis, while section six concludes by reflecting on the wider implications of those results and on potential avenues for further research. The article is complemented by an online appendix providing further descriptive statistics of the variables used, and robustness checks for the analyses.

The context: fifteen elections in one decade

According to several scholars, in recent decades Europe has seen a destabilisation of its party systems and a restructuring of its political space (Hernandez and Kriesi, Reference Hernandez and Kriesi2016; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Kriesi and Vidal2018; Jackson and Jolly, Reference Jackson and Jolly2021). The problems connected to the economic and immigration crisis have probably contributed to anchoring those dynamics to the voting behaviours of the electorate, with Eurobarometer survey data confirming a generalized inclusion of immigration, alongside unemployment and other economic issues, amongst the most important problems to be addressed by European countries (Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022).

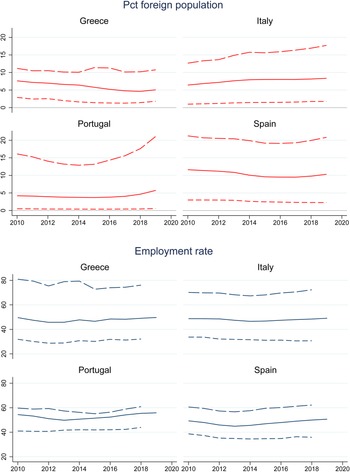

Public perceptions do not necessarily go hand in hand with objective data, and in the graphs in Figure 1 we outline for each of our South-European countries the annual national employment rate and percentage of the foreign population (solid line), together with its maximum and minimum values (long and short-dashed lines) in one of its territorial units.

Figure 1. Employment rate and percentage of foreign population in four South-European countries.

The graphs delineate multiple forms of variation that can be exploited in a comparative analysis. There is a first rough cross-country variation, with Portugal systematically outperforming the others in terms of employment rate, and Spain having always the largest foreign population for the whole decade. Additionally, there are different dynamics on the longitudinal dimension, with increasing, decreasing, and stagnating trends on both variables (more details in the online appendix). And there are different within-country magnitudes of variation, with countries appearing more homogeneous on certain factors – like Portugal for its economy and Greece for the share of immigrants – and more heterogenous on others – Spain for immigration and Greece for the economy, and less or more skewed, like Portugal on the share of foreigners, whose highest values are much farther away from the national average than are those of the other countries. Finally, the aforesaid within-country variation is approximately constant throughout the decade for some countries, or it has its own trend, like the increasing range in the share of the foreign population in Italy and the curvilinear dynamic again for Portugal. Overall, the overlap of these multiple layers of variations provides an exceptionally rich research environment in which to test their association with specific electoral behaviours.

Indeed, as anticipated by the comment of the EU commissioner, it is likely that those two issues played a prominent role in the legislative elections that took place in Southern Europe in those years. There were many of them during that decade, also because both Greece and Spain had to immediately return to the polls twice in a row because of the inconclusiveness of the preceding electoral results. In the four major South-European countries, citizens were asked to turn out fifteen times for a legislative election, with outcomes mostly confirming the ‘electoral and government epidemics’ that started with the Great Recession (Bosco and Verney, Reference Bosco and Verney2012, Reference Bosco and Verney2016). In this period, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain elections exhibit some common trends and dynamics.

The first shared feature is the continuation of the declining turnout that has already been pointed out by Morlino and Raniolo (Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017). There are certainly significant national idiosyncrasies due to cultural and institutional factors, but the occasional improvements in some critical elections – like the January 2015 ballot in Greece or the April 2019 ballot in Spain – cannot mask the decrease in electoral participation. The gap in turnout between the last election of the period and that of the previous decade ranges from 7.6 percentage points for Spain and Italy, through 11.1 points for Portugal, to 13.1 points for Greece. Survey data confirm that, while the decline in turnout was initially paralleled by a similar decrease in satisfaction with democracy, as well as trust in political actors and institutions, the trends started to diverge in the second half of the decade, with a more or less pronounced recovery in the legitimacy indices (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, Reference De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira2020). Interestingly, whilst the demobilizing trends were triggered by a lack of confidence in the capacity of the incumbent government to tackle public problems, they also contributed to the survival and confirmation of those same political élites.

However, the period was not characterised only by electoral and political alienation. ‘Politics has certainly become a lot more fluid and unpredictable (…), with the emergence of public protest, the rise of new political parties, the formation of new coalitions of pre-existing parties and, in some cases at least, the demise of long-standing political entities, whether individuals, political parties or both’ (Parker and Tsarouhas, Reference Parker and Tsarouhas2018: 206). Increased fluidity means less ideological attachment, a greater disposition to change vote, including support for inexperienced leaders, and ultimately more random and contingent electoral outcomes.

The most direct measures of dynamics of this type are the various indicators of volatility made on the bases of the original aggregate Pedersen index (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen1979). Using the quantities computed by Emanuele (Reference Emanuele2020), the four South-European countries had average total volatility for the decade equal to 20.8, with maximum levels reached by Greece in May 2012 (48.5), Italy in 2013 (36.7), Spain in 2015 (35.5) and Portugal in 2015 (13.8). Increased instability is not a prerogative of Southern Europe, and yet the regional average value is 5 points higher than the one for the remaining European countries, and it is more than double the one in the previous decade for the same four nations. On looking at the so-called ‘volatility by regeneration’ (Chiaramonte and Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2015) – that is, the component of the overall measure that concerns solely the new entries to and exits from each political system in each election – the average value for the four South-European countries is approximately equal to 6, corresponding to almost 30% of the overall volatility. That same component in the other European countries is only equal to 0.7, accounting for just 7% of their overall volatility.

In sum, the level of electoral instability in the four systems analysed in this article was exceptionally high between 2010 and 2019. ‘Electoral earthquake’, ‘tsunami’, ‘breakdown’, have been expressions repeatedly used by scholars to denote the magnitude of the changeovers produced in those elections (Chiaramonte, Reference Chiaramonte, Fusaro and Kreppel2014; Teperoglou and Tsatsanis, Reference Teperoglou and Tsatsanis2014; Orriols and Cordero, Reference Orriols and Cordero2016; Schadee et al., Reference Schadee, Segatti and Vezzoni2019). The volatility was systematically triggered by the entry of new parties, like the Five Star Movement in Italy (Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015) and Ciudadanos and Podemos in Spain (Orriols and Cordero, Reference Orriols and Cordero2016), or by the sudden success of parties that had had a lower profile in the past, such as SYRIZA in Greece (Tsakatika, Reference Tsakatika2016) and the Northern League again in Italy (Chiaramonte et al., Reference Chiaramonte, Emanuele, Maggini and Paparo2018). Only Portugal seemed to have eschewed most of those novelties (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, Reference De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira2020).

Such sequences of unsettling ballots had predictable consequences on the party systems as regards both their formats and mechanics (Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017). In Greece, the index of the effective number of electoral parties increased almost threefold – from 3.2 to 9.0 – in the 2012 election, while the corresponding parliamentary index increased from 2.6 to 4.8 (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020). It gradually decreased thereafter, though remaining slightly higher than the pre-crises period. With Greece's 2019 ballot, the system seems to have returned to a traditional two-partyism with single party-majority governments, despite having substituted one of the two contenders and only after experiencing grand coalitions and alliances between odd partners (Teperoglou and Tsatsanis, Reference Teperoglou and Tsatsanis2014; Tsatsanis et al., Reference Tsatsanis, Teperoglou and Seriatos2020).

Italy's hesitant bipolarism gave way in 2013 and 2018 to a tri-polar dynamic; the effective number of parties rose to more than five in terms of votes, and more than four in terms of seats. The mutual distrust amongst the relevant parties produced fragile coalitions and the need to resort to non-elected prime ministers, or even to technocratic governments (Ceccarini and Newell, Reference Ceccarini and Newell2019). There remain unresolved causes of instability, so that it is difficult to consider the 2018 ballot as the origin of a new stable pattern of cooperation and competition amongst parties (Pinto, Reference Pinto2020).

Portugal's party system was the least affected by the long-term impact of the recession and events of the decade: its indices of fragmentation fluctuated more or less at the same level as in the previous period. However, new coalitional dynamics emerged after the 2015 ballot, opening unexplored political combinations and signalling further opportunities for renewal in the future in an otherwise resilient system (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2019; Lisi et al., Reference Lisi, Sanches and dos Santos Maia2020).

The Spanish model, with its moderate two-partyism able to govern the tensions across the centre-periphery cleavage, was one of the most affected. The challenges of the new fragmented and polarised party-system, and the constitutional crisis with the autonomous community of Catalonia prove how the decade was an important juncture for the Spanish political system (Rodon, Reference Rodon2020; Simón, Reference Simón2020a, Reference Simón2020b). The indices regarding the effective number of parties, now constantly twice higher than those before the recession and amongst the highest in Southern Europe, confirm the transformation of the old model.

The theory: retrospective voting on multiple issues?

‘Retrospective voting’ means that voters look systematically at the past performance of the incumbent parties to cast their ballot, either confirming them in power or punishing them (Key, Reference Key1966). This does not mean that each and every voter does so, or that more or less large portions of the electorate do not consider other factors in their vote choices, including the ideology or policy platform of the various parties, the appeal of their leaders, or their personal political affection. It only means that a sizeable group of voters, large enough to trigger a systematic electoral outcome, use that kind of backward-looking evaluation as a voting heuristic.

When assessing past events, actions and performances, the theory does not require voters to be omniscient, perfectly rational and informed, or able to conduct a balanced review of the outcomes of a wide set of policies (Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981). Quite the opposite. Exactly because it would be unrealistic to make such bold assumptions about voters' knowledge and rationality, retrospective judgements are useful cognitive shortcuts for an otherwise complex choice. That means that voters may be myopic, with a limited time horizon, and that only selected salient issues capture their political attention (Achen and Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2016).

Because of its constant and ubiquitous importance, the state of the economy is the dimension that scholars agree voters most often use to judge the capacities and performance of the incumbent government. This has given rise to a specific strand of the retrospective voting literature that, by focusing on the subjective perceptions or objective conditions of the economic situation, has taken the name of ‘economic vote theory’ (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck, Stegmaier, Dalton and Klingemann2007; Stegmaier and Lewis-Beck, Reference Stegmaier and Lewis-Beck2013). The essence of the theory is simple, since it is based on a straightforward reward-punishment hypothesis, with voters punishing the incumbent government in the case of poor economic performance, and rewarding it in the case of good outcomes.

In spite of the simplicity of the hypothesis, the mechanisms driving those reactions are more complex, and they are still debated. Considering only those studies that look at the objective conditions of the economy, voters may react to the economic situation for various reasons: as a sort of ‘sanctioning reflex’; because they have expectations about the future on the basis of past accomplishments; because they signal to their agents that poor performances will not be tolerated; because they derive from the state of the economy information regarding the actual abilities of the incumbent government (Franzese and Jusko, Reference Franzese, Jusko, Weingast and Wittman2006; Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008).

Whatever the mechanism triggering the reward-punishment hypothesis may be, the observed economic conditions are typically homogeneously evaluated by the electorate: in other words, they have to be considered a valence and not a position issue (Stokes, Reference Stokes1963). While the character of any problem is something that should be ‘settled empirically and not on a priori logical grounds’ (p. 373), ‘the issues of economic well-being probably come as close as any in modern politics to being pure ‘valence’ issues’ (Butler and Stokes, Reference Butler and Stokes1974: 370).Footnote 2 The electorate unambiguously prefers growth over a recession, and employment over unemployment, and this, coupled with the salience of the issue, is the main reason why there is abundant empirical literature confirming the association between a good/bad state of the economy and the electoral reward/punishment of the incumbents (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck, Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2019).

Since the Great Recession, that association has been further validated also in extraordinary times (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck, Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2014; Hernandez and Kriesi, Reference Hernandez and Kriesi2016; Lewis-Beck and Lobo, Reference Lewis-Beck, Lobo, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis-Beck2017; Giuliani and Massari, Reference Giuliani and Massari2019), and even more so in the South-European countries covered by the present analysis (Parker and Tsarouhas, Reference Parker and Tsarouhas2018; Lobo and Pannico, Reference Lobo and Pannico2020; Morlino and Sottilotta, Reference Morlino and Sottilotta2020).

Adopting a subnational and yet comparative approach (see infra) only marginally complicates the issue. Bosch (Reference Bosch2016) identifies eight possible combinations of the retrospective economic vote, depending on who is evaluated by the voters – the national incumbent or the regional one – in which type of ballot – a national election or a regional one – and on which economic situation – the national state of the economy, rather than the local one.

Alongside some genuinely local economic voting, regional elections have been often found to reward or punish parties in government at the national level, either because of the national economic situation – the so called ‘second-order economic vote’ – or depending on the local state of the economy – something that has been dubbed ‘coattail economic vote’ (Fauvelle-Aymar and Lewis-Beck, Reference Fauvelle-Aymar and Lewis-Beck2011; Bosch, Reference Bosch2016; León and Orriols, Reference León and Orriols2016; Thorlakson, Reference Thorlakson2016). Since this evidence related to local elections refers to centralized countries like France, federal states like Germany, and semi-federal ones like Spain, a similar retrospective attribution of responsibilities to national incumbents would be plausible also in the case of our four South-European countries.

A fortiori, this should be true for our analysis that focuses on legislative elections and uses sub-national data only to establish the link between the economy and electoral behaviours at a more fine-grained level. Indeed, most studies confirm that the success of national incumbents is systematically associated with the local economic situation in contexts as diverse as France (Auberger and Dubois, Reference Auberger and Dubois2005), Canada (Cutler, Reference Cutler2002), Italy (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2017, Reference Giuliani2022b), Portugal (Veiga and Veiga, Reference Veiga and Veiga2010), the United Kingdom (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Pattie, Dorling, MacAllister, Tunstall and Rossiter2000), and the United States of America (De Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw, Reference De Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw2020).

Thus, under the demanding conditions posed by a within-country and yet comparative approach, our first expectation is the customary one:

Hp. 1 Economic vote hypothesis: The better the state of the economy, the better the electoral performance of the national incumbents.

As showed by Eurobarometer surveys, immigration was often the second most important problem perceived by the population. With or without an actual upsurge in the number of migrants in our four countries, the asylum crisis and the increased politicization of the problem brought the management of the issue to the forefront of the electorates' concerns (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Ferejohn and Paparo2020; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022). Indeed, the political salience of the immigration issue was not driven by humanitarian reasons, since the presence of foreigners is felt as a socio-economic, securitarian or cultural problem much more than an opportunity (Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier, Donnelly, Bermeo and Bartels2014).

Both left and right mainstream parties may be ‘uncomfortable’ in front of their electorate for the increased presence of foreigners. The former because the ‘inflow of workers can lower the wages of the native working class and potentially strain the welfare state’, while for the latter ‘the cultural diversity that follows does not mesh well with (their) desire to preserve the nation's ethnocultural heritage’ (Dancygier and Margalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020: 739). In any event, governing parties ‘would be surrounded by more extremist voices on the left and the right’, exploiting the mounting dissatisfaction and ‘potentially leading to a growing fragmentation of the vote’ (740). Mainstream parties of different leanings can try to adapt to the welfare chauvinism of their competitors (Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016), but can be seldom credible in following them on a generalized critique of immigration flows.

If this is true, punishing the incumbents for an increasing presence of immigrants would not transfer those votes to a different mainstream opposition party; rather, it would disperse them among newer and more radical parties, a pattern that has already received some confirmation in several South-European countries (Vasilakis, Reference Vasilakis2018; Lisi et al., Reference Lisi, Llamazares and Tsakatika2019; Mendes and Dennison, Reference Mendes and Dennison2021). Even if the immigration issue has not the same valence character as the economy, if the elastic portion of the electorate considers the increase in the share of foreigners as damaging their welfare prospects and opportunities, the management of immigration flows could simply represent another ‘competence signal’, a shortcut on which the capacity of the incumbent government is judged retrospectively, independently from its ideological inclination.

Accordingly, we thus advance the following expectation:

Hp. 2 Immigration vote hypothesis: The larger the increase in the share of immigrants, the worse the electoral performance of the national incumbents.

The natural alternative to this expectation is not simply the null hypothesis, but a more positional characterization of the immigration issue. Indeed, voters may have different opinions regarding the appropriate levels of immigrants in their country, with some of them having no problems with a multicultural society or accepting a larger number of immigrants for humanitarian reasons, and some others preferring a reduction in their presence. These opinions may be connoted along the traditional left-right continuum (Lehmann and Zobel, Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018), with leftist parties framing the immigration issue differently from rightist ones (Gianfreda, Reference Gianfreda2018; Urso, Reference Urso2018). This would have asymmetrical electoral consequences depending on the political leaning of the incumbent government.

In fact, the presence and flows of migrants have been found to be associated with a vote in favour of populists and rightist parties in Greece (Vasilakis, Reference Vasilakis2018), Italy (Barone et al., Reference Barone, D'Ignazio, de Blasio and Naticchioni2016; Abbondanza and Bailo, Reference Abbondanza and Bailo2017; Albertazzi and Zulianello, Reference Albertazzi and Zulianello2021), Spain (Mendez and Cutillas, Reference Mendez and Cutillas2013; Mendes and Dennison, Reference Mendes and Dennison2021), and in other European countries (Halla et al., Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017; Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2017; Otto and Steinhardt, Reference Otto and Steinhardt2017; Edo et al., Reference Edo, Giesing, Öztunc and Poutvaara2019). In these circumstances, leftist governments may be punished more than rightist ones because of their more tolerant attitude. Conversely, since what we are trying to explain is not the party choice, but the continuing consent for an incumbent government, the rightist electorate may be the one that decides to withdraw its vote from a previously supported conservative government, while the leftist voters will continue to choose their usual progressive parties, and they may even reward the outcome of their more inclusive policies. In sum, we advance two rival interpretations for a positional characterization of the immigration issue.

Hp. 3a The larger the increase in immigration, the worse the electoral performance of left-wing national incumbents

Hp. 3b The larger the increase in immigration, the worse the electoral performance of right-wing national incumbents

Finally, worth considering are some conjectures regarding the interaction between the two dimensions presented above. Statistically speaking, the idea is that a multiplicative rather than an additive model better fits the retrospective judgment of the voters. Intuitively, in a decade characterized by the economic adjustments needed to cope with the fiscal leftovers of the Great Recession, the competition for welfare resources triggered anti-cosmopolitan attitudes that were probably more intense in the contexts in which the crisis provoked greater economic distress. If some kind of retrospective immigration vote exists, it should thus be stronger where one also expects a retrospective economic vote.

That possibility is theoretically grounded in the fact that, according to the literature on welfare chauvinism, subjective economic insecurities add to the objective uncertainties in the presence of ethnically or culturally different population groups (Kros and Coenders, Reference Kros and Coenders2019; Careja and Harris, Reference Careja and Harris2022). ‘Individuals who face economic insecurity due to the processes unleashed by globalisation are especially susceptible to ethnocentrist, anti-immigration appeals’ (Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier, Donnelly, Bermeo and Bartels2014: 148).

Alternatively, each one of the two dimensions could be enough to trigger the reactions of the relevant elastic electorate, saturating the possibility of rewarding or punishing the incumbents. In this event, the state of the economy and the immigration trends could mutually compensate their electoral effects, rather than reinforce each other. A conditional model would still be preferred to a simple additive one, but with a different sign of the interaction coefficients. To sum up:

Hp. 4a The economic situation and immigration trends mutually reinforce each other in affecting the electoral performance of the national incumbents.

Hp. 4b The economic situation and immigration trends mutually compensate each other in affecting the electoral performance of the national incumbents.

Clearly, if one of the two previous partisan-specific hypotheses were to be confirmed, also these types of conditional expectations would need to be tested separately for left and right-wing incumbent governments.

Data and method: a subnational cross-country multi-election approach

Our research adopted subnational NUTS3 territorial units of analysis.Footnote 3 Although less frequent than the usual cross-country approach, subnational within-country analyses with objective data are not entirely new in the study of voting behaviour, and have been conducted also for some South-European elections (Martins and Veiga, Reference Martins and Veiga2013; Riera and Russo, Reference Riera and Russo2016; Abbondanza and Bailo, Reference Abbondanza and Bailo2017; Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2017, Reference Giuliani2022b; Vasilakis, Reference Vasilakis2018; Bratti et al., Reference Bratti, Deiana, Havari, Mazzarella and Meroni2020).

From a theoretical point of view, relying on the local state of collective problems is a more credible sociotropic approach to retrospective voting: it is a sort of mid-way between selfish pocketbook concerns and distant country averages that has been dubbed ‘economic localism’ (Cutler, Reference Cutler2002) or ‘communotropic perspective’ (Rogers, Reference Rogers2014). From a methodological perspective, the main advantage of this approach is that it grants a higher degree of control on potentially confounding variables, thus representing a more demanding test for the hypotheses researched. The downside of single within-country analyses is the possible limited variation of some variables that could mask the overall contribution of those subnational units to a more general explanation of voting behaviour.

This shortcoming is tackled by cumulating multiple sets of subnational observations, adding territorial units both cross-country and longitudinally. This was the approach followed in our research, where we compared NUTS3 units in four countries in eight elections, two for each political system, one in the first half and one in the second half of the decade under investigation.Footnote 4 This produced a ‘stacked dataset’ in which each territorial unit was nested within a country and presented two observations, one for each election covered by the analysis. The structure of the data required the use of multilevel cross-classified regression models with random country-election intercepts.

Regarding operationalisation, the dependent variable was measured by the percentage of votes received by the incumbent parties at the chosen subnational level, and it was matched in the right-hand side of the equation by the corresponding quantity in the previous election. Considering the support for all coalition partners is to be preferred to focusing only on the party of the head of government in order not be biased by potential within-coalition transfer of votes.Footnote 5

The situation of the economy is usually measured by means of indices checking trends in GDP or labour market statistics. In the long aftermath of the Great Recession, level indices tend to better reflect the actual distress experienced by the population, whose well-being can only be marginally affected by any short-term recoveries that may be shown by trend indices. However, we decided to include both types of variables in our models and, in order to maximize consistency, we chose the Eurostat employment rates and growth measured at NUTS3 level.Footnote 6

Regarding immigration, we included in our models the change in the share of the foreign population against the previous year, which can be computed at a disaggregated level from the data issued by national institutes of statistics. In this case, choosing a trend variable partially isolates it from the preferences regarding the absolute favoured level of immigration in a certain country or area, as well as reducing the risks of spurious relationship due to differences in the structure of the local economy. In any case, in the online appendix we also experimented with the more traditional level of immigration measured as a share of foreign citizens.

The conditional third hypothesis requires a measure of government partisanship. For this purpose, we used the seat share of social democratic and other left parties in government, measured as a percentage of the total parliamentary seat share of all governing parties in the last year before the election, extracted from the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Engler and Leeman2021). Our empirical cases cover the entire range of the potential 0-100 variation of this measure, from the Rajoy and Passos Coelho cabinets, with 0% seats of leftist parties respectively in Spain and Portugal, to the Tsipras and Costa governments, with respectively 93.6% and 100% in Greece and Portugal. In the online appendix we show how substantially similar results are obtained with different categorical operationalizations.

Apart from the country-election fixed effects accounted for by the multilevel specification, and the partisan local traditions included in the lagged dependent variable, we incorporated a set of control variables. The first was a dummy to check for coalition governments, whose inclusion had a double rationale. On the one hand, since the work by Powell and Whitten (Reference Powell and Whitten1993), coalition governments have often been supposed to blur the incumbent parties' responsibilities, something that would produce a decrease in the magnitude of the retrospective vote. On the other hand, a sheer statistical effect derives from the fact that the larger the popular support, the more severe the possible punishment in difficult times, which entails some fixed negative effects of coalition governments.

The second control variable was the change in turnout compared to the previous election, which accounted for the fact that retrospective dissatisfaction could lead to increased abstentions instead of being funnelled into the punishment of the incumbents (Weschle, Reference Weschle2014), something that has been reported to happen in several of the elections covered by the analysis (Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017). Finally, we included two variables normally associated with a specific pattern of voting behaviours in individual-level studies, namely the urban density of the area and the share of the old-age population.

The results

Given the multilevel structure of the data, with subnational observations collected for multiple elections in four different countries, the first thing to do was verify the appropriateness of a multilevel approach. A likelihood-ratio test on the empty model explaining the support for the incumbent government parties confirmed that our cross-classified model was preferable to a standard OLS regression. As detailed in the online appendix, the mean support was slightly higher than 30%, while from the random part of the model it is apparent that approximately 60% of the variation depended on cross-country and cross-election differences.

Table 1 presents a series of models testing our first expectations. We started with the economic vote hypothesis, then introduced the immigration vote hypothesis, and finally tested the conditional expectations including the partisanship of the government. All these models explained the additional mobile support compared to a baseline loyal vote, captured by the lagged dependent variable, which our regressions estimated at being around 65% of the previous support. That same variable also reflected any specific geographical pattern of the vote for the incumbent government parties, and thus of the variable for within-country differences in partisanship.

Table 1. Explaining the electoral support for the incumbent governments (cross-classified multilevel regression)

Standard errors in parentheses: *** P < 0.01, ** P < 0.05, * P < 0.1.

Before illustrating the results concerning our covariates of interest, we now comment on the coefficients of the control variables, whose influence is sufficiently stable across all models reported in Table 1.

The dummy for coalition governments has a negative and highly significant coefficient, meaning that, all other things being equal, coalition governments lose more than single-party cabinets. This additional effect can be probably attributed to a direct statistical consequence of the larger sizes of coalitions, while it is certainly at odds with any expectation regarding a generalized blurring of the responsibilities in the case of multi-party governments. In fact, Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck (Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2017) already raised some doubts regarding institutional confounding effects of this sort, while it is clear that large coalition governments risk losing more votes than minority single-party cabinets do.

Change in turnout also has a negative influence on the incumbents' electoral performance, which is systematic in most of the tested models. This means that, ceteris paribus, the higher the electoral participation, the greater the punishment for governing parties. Alienation and abstention, driven by potentially similar negative retrospective judgments, paradoxically increase the incumbents' chances of remaining in power, something that resonates with the findings of the qualitative literature on the electoral results in the four countries. Furthermore, urban areas with higher population density, and areas characterized by relatively older residents seem to be more conservative in regard to the punishment of incumbent parties, marginally contributing to their confirmation. However, only the coefficients of the second variable are consistently statistically significant across all models.

Model 1 presents a standard retrospective vote model, with the two economic indices capturing the shortcuts used by citizens in order to evaluate the management capacity of the government. The coefficients of both variables have the expected positive sign, although only the one for the employment rate is also highly statistically significant. This confirms our belief that level economic variables are preferable to trend indices since, especially in troubled periods like the decade we are investigating, the latter may register sudden variations that do not reliably reflect a healthier economic situation. Similar results in regard to the effect of levels and trends in unemployment on voting behaviour have been found when analysing a large number of elections for 38 advanced democracies before and after the Great Recession (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2019). While, in normal times, economic improvements tend to stabilize into a new plateau of wellbeing, this does not happen in complex periods. In the latter, it would be much more cognitively demanding to assume that citizens comparatively evaluate present and past situations, instead of simply assessing the actual state of the economy in their surroundings.

For each percentage point of the employed population, the incumbent party obtains approximately one-tenth of a percentage point more votes on top of the aforementioned baseline loyal support. The apparently small magnitude of the effect should not be misunderstood, however. The average employment rate of the sample was around 46%. Its range across all territorial units was almost 50%, which means that there was a direct differential effect of five percentage points in additional electoral support due only to this variable, whose effects in the distribution of seats was then multiplied by the disproportionality of the electoral system, substantially affecting the government's survival.

Model 2 adds the immigration trend as a potential source of retrospective judgement. While all the economic and control variables keep approximately the original magnitude and statistical significance, the coefficient for immigration is negative, as expected, but only weakly significant (P < 0.1). The increase in the presence of foreigners seems to act as a possible cognitive shortcut triggering some retrospective judgements regarding the management capacity of incumbent governments, at least in the electorate open to the possibility of changing vote across elections. However, its borderline statistical significance leaves open the possibility that, in the comparison, the average effect could be empirically driven just by a subset of our observations.

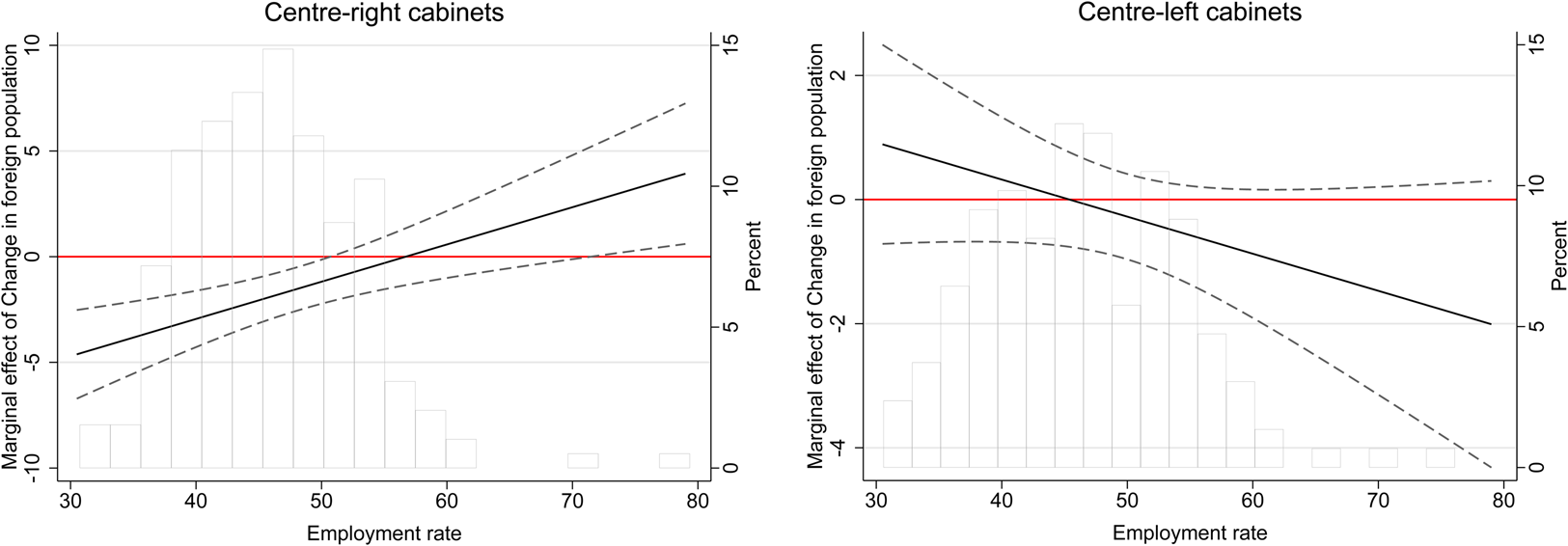

The theoretical reason for this empirical limitation may concern the remarks that led us to formulate our third rival hypotheses concerning the mediating role of government partisanship. Model 3 introduces this conditional effect on the role played by immigration, interacting that variable with the share of government seats occupied by leftist parties. As is now well known, the coefficients of multiplicative models should not be directly commented. Instead, one should plot the marginal effects of the relevant variable at different quantities of the conditional factor, as we have done in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of immigration for different political leanings of government parties (point estimate and 95% confidence intervals).

The graph of the marginal effects supports the interpretation of our hypothesis 3b that the electors of right-wing governments abandon the parties that they previously voted for if they are incapable of controlling the flux of immigrants; and it contradicts hypothesis 3a that presumed larger losses for leftist governments. The effect of immigration trends is systematic until the presence of right-leaning parties becomes clearly minoritarian, i.e. for about two-thirds of the overall compositions of the incumbent governments. Obviously, this does not mean that the rightist electors then decided to vote for more inclusive leftist parties; it is much more likely that they chose even more radical rightist leaders, or voted for some new populist party. Those rightist governments in Southern Europe included mainstream parties like New Democracy in Greece, the People's party in Spain, and the Social Democratic party in Portugal; parties which had more extreme and nationalist opposition alternatives also to their right.

On the contrary, the support for more leftist cabinets seems indifferent to immigration trends, consistently with the previous observation regarding the average effects of hypothesis 2 being actually triggered by just a subset of the observations. In the online appendix, alternative specifications of this partisan conditioned hypothesis confirm the negative electoral effect of an increase of immigration for incumbent cabinets characterized by a rightist hegemony, while extending the area of indifference (if not gains) to more moderate centrist governments.

Finally, because of these results, hypotheses 4a and 4b regarding the interaction between our two dimensions need to be tested separately for right and left-leaning cabinets, simply defined by the minority or majority status of leftist parties in government (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Engler and Leeman2021). The complete set of coefficients is reported in the online appendix, while here we plot in Figure 3 the marginal effects of the immigration variable at varying levels of the employment rate.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of immigration on the incumbents' electoral support at varying levels of employment rates and for different types of incumbents (point estimate and 95% confidence intervals).

For centre-right cabinets, representing approximately 40% of our observations, the first panel of Figure 3 confirms the mutually reinforcing character of the two retrospective dimensions, as it has been postulated in hypothesis 4a. The negative impact of immigration is stronger where the employment levels are low, while it cannot be distinguished from zero as soon as the conditions of the labour market are better, that is with an employment rate above 50%, something that regards only one-fourth of the territorial units governed by right-leaning governments. This evidence is coherent with a theoretical explanation that considers the competition for labour and for welfare protection in globalized settings. Tougher economic conditions aggravate that competition and activate its political potential, producing the observed electoral consequences for incumbent governments (Dancygier and Donnelly, Reference Dancygier, Donnelly, Bermeo and Bartels2014).

For centre-left cabinets, represented in the second panel of Figure 3, both hypotheses 4a and 4b are disconfirmed. The slope of the marginal effects of immigration seems to suggest a better fit for the compensation hypothesis, with each of the retrospective dimensions activating itself only when the other one is less problematic, but the confidence intervals are so large that it is simply impossible to reject the null hypothesis. As in Figure 2, immigration fails to reach any sufficiently systematic effect on the electoral prospects of leftist incumbents even when conditioned by the state of the economy,

Conclusion

To synthesise our findings, voters punished the incumbent government parties when and where the economic situation was bad, and they sometimes did so also when and where immigration was increasing. The latter dynamic was conditioned by the partisan composition of the cabinet, with punishment being limited to those dominated by right-wing parties whose electorates probably felt disappointed by the incapacity to govern the immigration problem more rigidly. Furthermore, for these incumbents, the two dimensions mutually reinforced each other, with the negative electoral effects due to the increasing foreign presence felt heavily in deprived economic contexts.

Our research design, which cumulated subnational observations in two elections each for four countries, suggests some further reflection on the interpretation of those findings. The limited number of groups prevented the modelling of cross-country differences, if not for their different intercepts, and yet a good part of the variation was at the level of individual observations. Our results do not say that within each of the four countries the two retrospective dimensions systematically triggered voting behaviours, and this not only because of the conditional effects of partisanship; rather, the effects surface thanks to the comparison of those subnational observations across the four countries.

Within each country, the more limited variation or a number of observations may prevent that effect from emerging, but their contribution to the overall picture is clear as soon as those observations are compared to the subnational data of the other nations. For example, Portugal had lower unemployment and fewer immigrants than the other three South-European countries for most of the decade; especially regarding occupation levels, it also had a lower internal variation across subnational units. However, once pooled with the provinces and regions of the other countries, Portugal's exceptionalism (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, Reference De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira2020) helps frame its territories within the wider interpretation of retrospective voting in Southern Europe: together with some of the units from those other countries, it populated the sample with several cases with smaller problems and less sanctioning of incumbents.

To paraphrase the common maxim, we can say that the whole is revealed by the sum of its parts, which cannot always be separately and independently understood. This concerns the very general idea of South-Europeanness. The shared belonging of the citizens of the four South European countries gives sense to their reactions, which are similar or different according to the objective problems that they experience, and not because they are resident in Galicia, Algarve, Sicily or the Attika region. This is a matter that should be further investigated, especially considering the possibility of including in the picture the idea of benchmarking (Kayser and Peress, Reference Kayser and Peress2012; Arel-Bundock et al., Reference Arel-Bundock, Blais and Dassonneville2021), i. e. the possibility that citizens compare the local performance to the corresponding national average, or to some past situation before the crisis period. These are research avenues normally precluded to cross-country studies, and to those relying on subjective evaluations. Our aggregated subnational approach is the first contribution in that direction.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2022.9.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Funding

The research has been founded by the Italian Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Universita` e della Ricerca: [Grant Number PRIN 2015P7RCL5].

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous referees of the journal, who rightly insisted to extend the analysis of the conditional effects of government partisanship; all remaining errors are my own.

Conflict of interest

The author reports no potential competing interest.