1. Introduction

The Korean language is known to have three different ways to derive passives (Sohn Reference Sohn1999, Song and Choe Reference Song and Jae-Woong2007, Yeon and Brown Reference Yeon and Brown2011). In the descriptive nomenclature, the first type is called the morphological passive, formed by attaching the verbal suffixes -i/-hi/-li/-ki, as shown in the alternations in (1).Footnote 1 Morphological passives are idiosyncratic in that they are only allowed with a limited set of transitive verbs, and the choice among the four suffixes -i/-hi/-li/-ki is lexically determined by the preceding verbal root. Thus, ccoch- ‘chase’ takes the suffix -ki, as in (1), but the choice varies with other verbal roots (e.g., sso-i ‘stung’, cap-hi ‘caught’, mwul-li ‘bitten’). Also notable is that the putative by-Agent in the passive alternant in (1b) is dative-case marked.

The second type are light verb passives. Light verb passivization applies to verbal nouns. In the active sentence in (2a), the light verb meaning ‘do’ is attached to a verbal noun to derive a verb. Its passive counterpart, -toy, which as a lexical verb means ‘become’, takes the place of -ha ‘do’ with the concomitant changes in the argument structure, as in (2b):

Finally, the third type of passives are called analytic or auxiliary passives, in which the suffix -eci is attached to a wide range of transitive verbs. With the suffixation of -eci to the verb in (3b), the Theme argument appears as the sentential subject and the Agent haksayngtul ‘students’ is optionally introduced by the adposition -ey uyhay ‘by’:

This paper is concerned with the last of the three alleged Korean passives, focusing particularly on the often overlooked distribution of the verbal suffix -eci. Because of the typical changes observed in passive formation in (3b), the verbal suffix -eci is generally treated as a passive morpheme (Park and Whitman Reference Park, Whitman and McClure2003; S. D. Park Reference Park2005; H. K. Jung Reference Jung2014a, Reference Jung2014b, Reference Jung2016a, among many others).Footnote 2 Within generative grammar, however, little attention has been paid to the fact that the same morpheme is used in a construction denoting potentiality or possibility, as in (4) (see Yeon Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015 and Mok and Kim Reference Mok and Kim2006 for descriptive and functional accounts; Nam Reference Nam2011 and Lim Reference Lim2015 for lexical semantic and l-syntactic perspectives; and Shibatani Reference Shibatani1985 and Fukuda Reference Fukuda2013 for a similar usage of Japanese -rare).Footnote 3, Footnote 4

The question arises as to why the same morpheme -eci appears in both constructions. This paper investigates the syncretism exhibited by the Korean verbal suffix -eci and the properties of the passive and potential constructions built upon it. I make two novel proposals. First, I argue that the syncretic morphology is not an instance of accidental homonymy, but rather is a result of -eci occupying an identical syntactic head — namely, v GO, the functional category that is associated with verbs of ‘change’ (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015). Second, I propose that their distinct syntactic patterns and meanings reflect their distinct structures with or without a higher functional head — VoicePASS. To substantiate these proposals, I link the usages of -eci in passives and potentials to the two other environments where -eci appears. I term these ‘derived change-of-state’ and ‘lexical inchoative’ constructions.

To the best of my knowledge, no attempt has been made in the theoretical literature to address all four usages of Korean -eci. In this paper, I show that recent developments in the theory of verb phrase (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006; Harley Reference Harley2013, Reference Harley, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017, among others), combined with the premise that morphological identity results from the morpheme occupying an identical syntactic head (Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015), enable us to systematically capture the characteristics of the constructions derived by -eci.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical background and assumptions involved. Section 3 illustrates some diverging syntactic behaviors of -eci as used in the passive and potential constructions. In sections 4 and 5, I propose an analysis of the passive and potential structures formed upon -eci. In particular, section 4 presents arguments that -eci realizes v GO, the verbalizing head that marks the eventuality of ‘change’ (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015) in both passives and potentials. Subsequently, I attribute the syntactic differences between the two constructions to the presence or absence of the functional head hosting an external argument in section 5. In the process, I examine the behaviors of the two additional -eci structures in the language and thus arrive at a synthetic account of -eci syncretism. In section 6, I ascribe the potential semantics to the interplay of the syntactic heads involved. Section 7 evaluates alternative hypotheses. Section 8 discusses some conceptual and typological implications that follow from the current system. Section 9 concludes.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Word formation in syntax

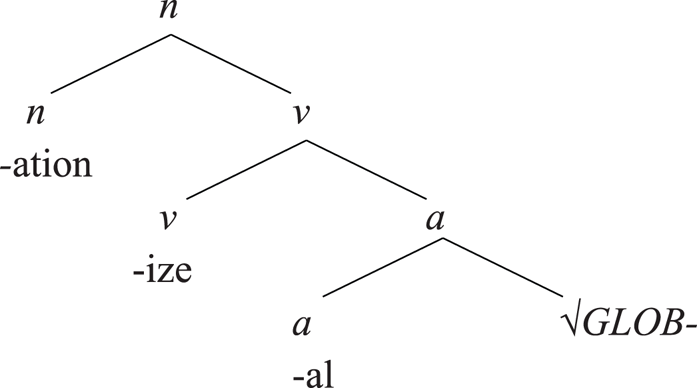

I assume that words are formed in syntax, using a Distributed Morphology (DM) framework (Halle and Marantz Reference Halle, Marantz, Hale and Keyser1993, Marantz Reference Marantz, Dimitriadis, Siegel, Surek-Clark and Williams1997). DM rejects the lexicon as a separate generative device and instead distributes its traditional roles throughout the distinct components of the grammar. Lexical items participate in syntax as category-neutral units, and their grammatical category is determined by the selecting functional head. For example, the English word globalization has an internal structure as in (5). The acategorial root √GLOB- is initially assigned the category of adjective by the selecting functional head a, which in turn is verbalized by v, and is finally derived as a noun by n. This syntactic derivation is transparently reflected in the morphological makeup:

(5)

Following this approach, verbal suffixes in Korean including -eci and -ha ‘do’/‘be’ have the status of an independent syntactic head. This view contrasts with lexicalist approaches (Williams Reference Williams1981, Anderson Reference Anderson1982, among others), where verbal stems with derivational suffixes attached enter syntax fully derived.

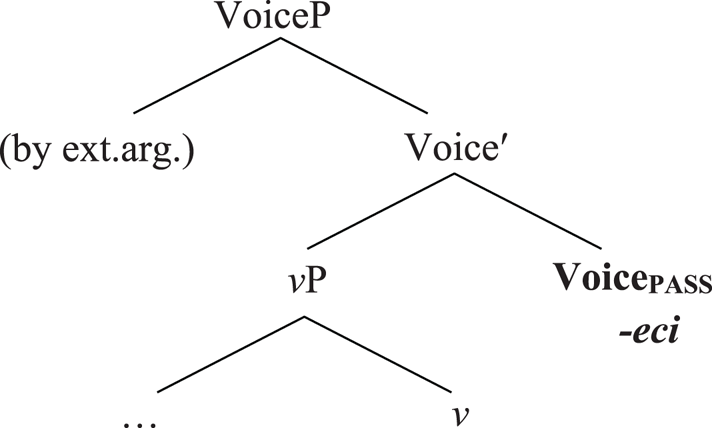

2.2. The tripartite VP hypothesis

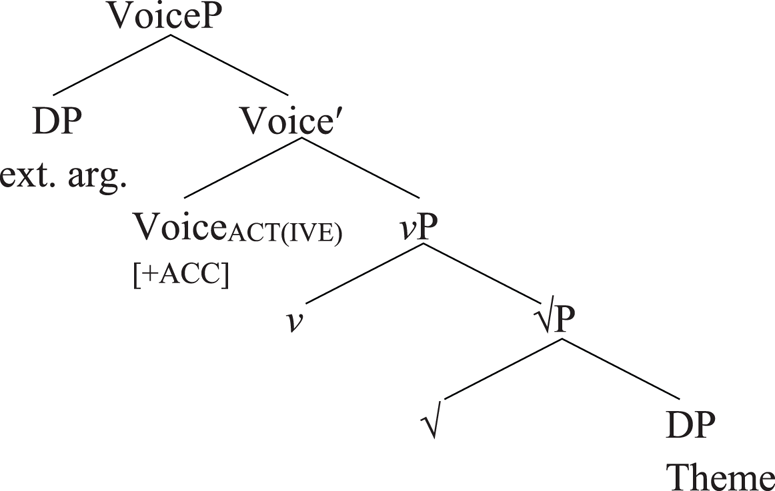

I further adopt the idea that the verb phrase consists of three layers, as in (6) (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006; Harley Reference Harley2013, Reference Harley, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017, among others). In (6), the Voice head introduces the external argument and is responsible for accusative Case in the active voice. The little v determines the syntactic category (‘verb’) of its complement and the kind of eventuality (e.g., be, do, caus, go/become) (Harley Reference Harley1995, Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003). At the bottommost level is the root, which is devoid of any categorial information (Marantz Reference Marantz, Dimitriadis, Siegel, Surek-Clark and Williams1997).Footnote 5 I assume that in passives, the passive alternant of Voice — VoicePASS — takes the place of VoiceACT (Harley Reference Harley2013).

(6)

Note that this premise departs from the traditional assumption that a core verb phrase is bipartite, containing a functional layer vP on top of a lexical layer VP (Hale and Keyser Reference Hale, Keyser, Hale and Keyser1993, Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995, Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Zaring and Rooryck1996, among many others). In what follows, I show that the separation of Voice from v, as schematized in (6), plays a pivotal role in explaining the various morpho-syntactic and semantic differences between passives and potentials in Korean (sections 4–6).

2.3. Syncretic derivational morphology

Cases where a certain morpheme participates in forming more than one construction are observed cross-linguistically. For example, the same voice morphology appears among passives, unaccusatives, and a limited number of reflexives in Modern Greek. Syntactic approaches to syncretism in derivational morphology have argued that this morphological identity reflects a common property in the syntactic component (Marantz Reference Marantz1984, Embick Reference Embick, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou and Everaert2004). Specifically, the absence of an external argument is the key property that links the three Greek constructions.

More recently, a particular version of this thesis states that morphological identity results from the morpheme occupying an identical syntactic head. Alexiadou et al. (Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015) propose that the syncretic verbal morpheme in Greek instantiates the same terminal node in syntax.Footnote 6 In what follows, I show that this assumption not only allows us to establish a comprehensive account of all the usages of -eci (section 4), but also provides a clue to the question of why the passive and potential constructions in Korean exhibit differences despite having the same morphology (sections 5–6).

3. -eci in passive and potential constructions

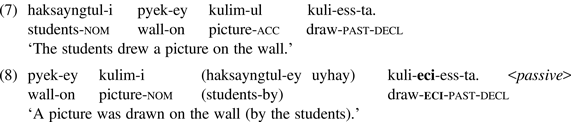

The verbal suffix -eci shows up in a typical passive construction in Korean, as previously discussed in (3b), repeated below as (8). Syntacticians thus generally analyze -eci as a passivizing head (Park and Whitman Reference Park, Whitman and McClure2003; S. D. Park Reference Park2005; H. K. Jung Reference Jung2014a, Reference Jung2014b, Reference Jung2016a, among others).

However, the same morpheme is found in a construction expressing potentiality or possibility, as in (4), repeated here as (9) (Yeon Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015; Mok and Kim Reference Mok and Kim2006; Nam Reference Nam2011; Lim Reference Lim2015).

The potential construction exhibits certain syntactic properties distinct from its passive counterpart. First, when -eci appears in the potential construction, it can attach to not only transitive verbs as in (9) but also intransitive verbs, as in (10) (Yeon Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015; Mok and Kim Reference Mok and Kim2006). This is not possible with canonical passives.

Second, the potential -eci construction is not compatible with a by-Agent (Lim Reference Lim2015). Examples (9)–(10) become unacceptable upon adding an intended external argument in the form of a by-phrase.Footnote 7 This is in sharp contrast to the passive -eci.

Before leaving this point, it is worth pointing out that an adverb like cal ‘well, easily’ and the negation marker an facilitate the potential meaning, as can be seen in (9)–(10). Note, however, that the compatibility with these elements cannot be used as a test for -eci as forming the potential construction, since they can appear in the passive as well. Thus, in what follows, I use these items to emphasize the potential meaning, not to distinguish it from the passive.

Examining the patterns of -eci in passive and potential constructions, three questions arise, to be answered in the following sections:

Q1: Why does -eci appear in both passive and potential constructions? (Section 4)

Q2: Why do passive and potential constructions formed with -eci exhibit distinct syntactic behaviors? (Section 5)

Q3: What is the source of the potential semantics? (Section 6)

4. -eci as a verbalizing head marking ‘change’

In this section, I argue that the Korean -eci suffix is a realization of the functional head v GO. My hypothesis regarding Q1 above is that -eci appears in both passive and potential constructions because it occupies the same syntactic head v GO. I present a two-step argumentation to substantiate this proposal. I first show that -eci is a phonological exponent of the v head, not Voice (section 4.1). I then present evidence that -eci instantiates a particular flavour of v — namely, v GO, which marks the eventuality of ‘change’ (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015) (section 4.2).

4.1. -eci as v, not Voice

I first argue that the suffix -eci attached to lexical verbs occupies the functional head v, not Voice. To arrive at this conclusion, the assumption adopted in section 2.3, repeated here as (13), plays a crucial part:

(13) Morphological identity results from the morpheme occupying the same syntactic

head (Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015).

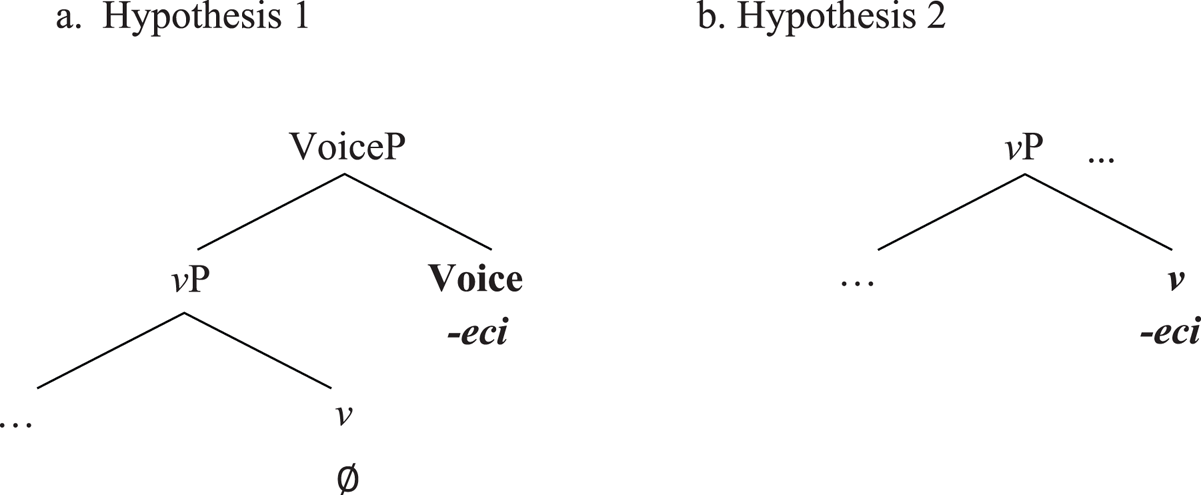

Given (13), the phenomenon whereby -eci appears in both passive and potential constructions is a consequence of -eci realizing a syntactic head that the passive and potential structures share. Assuming that Voice and v are separate syntactic heads, as depicted in (6), we have two analytical options as to which head -eci occupies. The suffix -eci may be hypothesized to realize either Voice or v, as represented in (14a) and (14b) respectively:Footnote 8

(14)

Recent theories of Voice diverge on the status of the implicit external argument in passives (Bruening Reference Bruening2012, Hallman Reference Hallman2013, Legate Reference Legate2014, Collins Reference Collins2018, Angelopoulos et al. Reference Angelopoulos, Collins and Terzi2020) and the possibility of Voice being semantically void (Schäfer Reference Schäfer2008, Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015, Wood Reference Wood2015, Myler Reference Myler2016, Kastner Reference Kastner2020, Tyler Reference Tyler2020). This means that Hypothesis 1 in (14a) can be fleshed out in several versions. For the purpose of this study, let us narrow down the question to whether the verbal suffix -eci occupies the verbalizing head or the higher projection above it.Footnote 9 A particular version of the first hypothesis is adopted in H. K. Jung (Reference Jung2014a, Reference Jung2014b, Reference Jung2016a), where the passive suffix is simply assumed to be the phonological exponent of the passive Voice head. However, broader empirical consideration favours the second hypothesis in (14b). Specifically, evidence for the second hypothesis comes from the other usages of -eci. In addition to its role to derive passive and potential verbs, -eci can also be suffixed to stative verbs, as in (15)–(16) (Kang Reference Kang1997, Zubizarreta and Oh Reference Zubizarreta and Oh2007, Lim and Zubizarreta Reference Lim, Zubizarreta, Demonte and McNally2012, Lim Reference Lim2015):

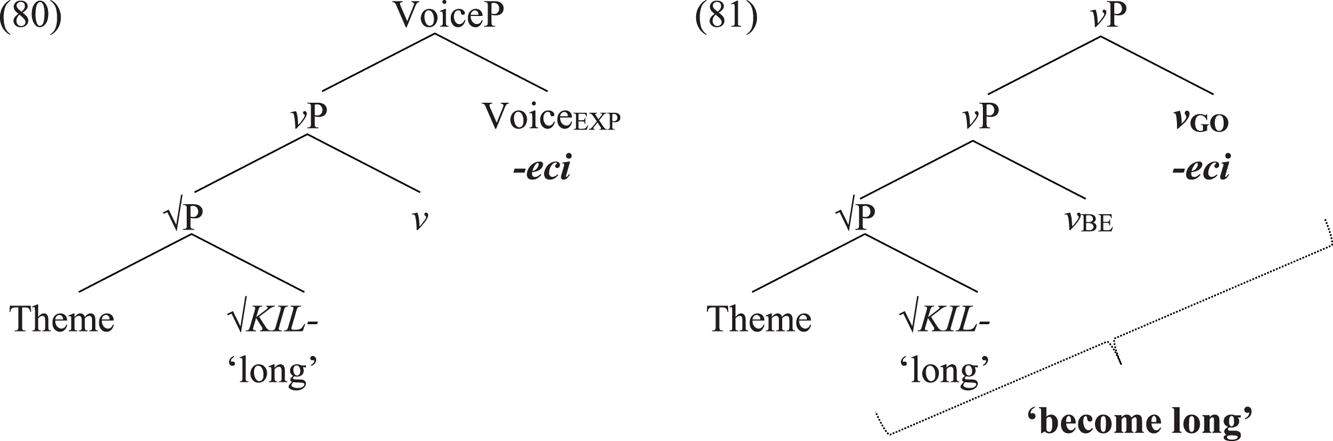

Under the current assumption of verbalizing heads (section 2.2), the stative verbs kil- ‘be long’ and hayngbok.ha- ‘be happy’ in (15a) and (16a) belong to the category of v BE (Harley Reference Harley1995).Footnote 10 The suffix -eci attaches to these stems to further derive change-of-state predicates in (15b) and (16b). Thus, I term the verbal stems in (15b) and (16b) derived change-of-state predicates.

In addition, the suffix -eci may also directly attach to a limited set of roots to derive inchoative verbs, as in (17b)–(20b) (Kang Reference Kang1997). The roots of these predicates behave like cran morphemes in that without -eci the verbal root fails to denote anything, as can be seen by the unacceptability of (17a)–(20a):

In (17b)–(20b), -eci evidently serves as a verbalizer. It is after the suffixation of -eci that the bound roots can be identified as verbs. In addition, the eventualities in (17b)–(20b) describe a ‘change’ in a state. I call this use lexical inchoative.Footnote 11

Notice that neither the derived change-of-state predicates in (15b)–(16b) nor the lexical inchoatives requiring -eci in (17b)–(20b) entail the presence of an external argument. This shows that these structures do not contain Voice licensing an external argument. Let us set aside the question of whether or not some kind of Voice is present in (15b)–(20b) for the moment, since the answer differs depending on one's theory of Voice.

Regardless, there is a consensus that v, not Voice, is the functional head responsible for assigning the category of verb to its complement, as in (17b)–(20b) (section 2.2). Moreover, the semantic effect of attaching -eci in (15b)–(20b) is precisely what the subcategory of v marking the eventuality of a ‘change’ in a state — v GO (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015), or its equivalent in Harley (Reference Harley1995, Reference Harley, Miyagawa and Saito2008) and Marantz (Reference Marantz, Dimitriadis, Siegel, Surek-Clark and Williams1997), v BECOME — is expected to yield. Thus, if we adopt the premise in (13) and, simultaneously, seek to account for the facts listed above, Hypothesis 1 in (14a) cannot fully explain the occurrences of -eci in (15b)–(20b). Only Hypothesis 2 in (14b) is compatible with all the usages of -eci, showing that -eci is v, not Voice.Footnote 12

Below I present some additional evidence that -eci instantiates the verbalizing head. I note that the transitive counterparts of the lexical inchoatives in (17b)–(20b) contain a lexical causative suffix, exhibiting the alternations in (21)–(24).

In Korean, the spell-out of lexical causative morphemes is determined by the individual roots they occur with (J.-W. Park Reference Park1994, Yeon Reference Yeon2000, Son Reference Son2006). H. K. Jung (Reference Jung2014b), Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008), Harley (Reference Harley, Miyagawa and Saito2008), and Miyagawa (Reference Miyagawa, Schertz, Hogue, Bell, Brenner and Wray2011) have independently shown that lexical causative suffixes are syntactically root-adjacent in Korean (and Japanese). In other words, lexical causative suffixes are a verbalizing v — v CAUS, in particular.Footnote 13 The systematicity of the morphological alternation in (21)–(24) strongly suggests that the -eci suffix and the lexical causative suffixes occupy a functional head of the same syntactic level. Since lexical causative suffixes are attested v CAUS morphemes, it is reasonable to think that -eci also instantiates a v — specifically, v GO/BECOME, which derives the inchoative counterparts in (21b)–(24b).

Finally, as pointed out by a reviewer, if certain verbal morphology can appear inside derived nominals with a deficient internal structure, this suggests that the morpheme is the spell-out of the verbalizing v head. In other words, if a derived nominal cannot appear with an Agent PP, the structure of the derived nominal lacks the Voice layer accommodating a syntactic external argument (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou, Giannakidou and Rathert2009, Harley Reference Harley, Giannakidou and Rathert2009). The verbal suffix inside the nominal cannot then be the Voice. To this end, the present analysis predicts -eci to be able to occur inside such derived nominals. The data in (25) demonstrate that the nominalizing morpheme -m can indeed nominalize verbs including -eci. The derived nominals in (25) result from nominalizing transitive verbal stems. Crucially, they do not allow a by-Agent, showing that the Voice that would otherwise be expected in the verbal domain is absent. It follows that -eci in (25) is not an instantiation of Voice but of a lower head, namely v.Footnote 14

On the whole, the patterns of -eci in the four exhaustive environments along with its parallel behavior with lexical causative suffixes and appearance in derived nominals uniformly point to the conclusion that -eci is a verbalizing v, not Voice.

4.2. -eci as vGO

Having established that the -eci suffix is a realization of v, I now turn to showing that -eci instantiates the flavour of go, which introduces verbs of ‘change’ as proposed by Cuervo (Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015). In this subsection, I demonstrate that while -eci may participate in deriving a ‘change of state’, the eventuality of become cannot be the core meaning of -eci. Specifically, the patterns of potential -eci in the perfect aspect lead one to conclude that -eci exclusively introduces the eventuality of v GO independent of v BE, supporting Cuervo's (Reference Cuervo2003) classification, at least in the Korean case at hand.

Recall the assumption about verb structure adopted in section 2.2. In addition to its role of categorizing its complement as verb, the v head names the type of eventuality that the resulting vP describes. Accordingly, Harley (Reference Harley1995) proposes a classification of the v head into a limited set of “flavours” such as v DO (activity), v CAUS (causation), and v BE (state). Cuervo (Reference Cuervo2003), albeit sharing the insight of v flavours, disagrees on the v flavour associated with the eventuality ‘change of state’.Footnote 15 Thus, while Harley (Reference Harley1995, Reference Harley, Miyagawa and Saito2008) and Marantz (Reference Marantz, Dimitriadis, Siegel, Surek-Clark and Williams1997) regard ‘change of state’ as a mono-eventuality, Cuervo (Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015) argues that become cannot be a component primitive enough to belong to the inventory of v flavours. Cuervo proposes that become should be further divided into v BE (the eventuality of ‘state’) and v GO (the eventuality of ‘change’). The constructions involving -eci provide a good testing ground for the two competing theories.

As shown in section 4.1, attaching the -eci suffix results in the verbal meaning of ‘change of state’ in the derived change-of-state predicate in (15b), repeated here as (26b) and the lexical inchoative in (27b).

In both (26b) and (27b), -eci delivers a ‘change’ meaning, but is it also responsible for the ‘be’ meaning? In other words, should -eci be identified as v GO or v BECOME? To answer this question, the interactions between the perfect marker -eiss and the constructions in which -eci appears need to be compared.

The perfect marker -eiss (lexically meaning ‘exist’) in Korean can be attached to change-of-state predicates to express the continuation of the resultant state (Son Reference Son, Svenonius and Tolskaya2008).

Just like the inherent change-of-state verbs in (28)–(29), -eiss can follow -eci in derived change-of-states (Zubizarreta and Oh Reference Zubizarreta and Oh2007) and lexical inchoatives, as can be seen in (30b)–(31b), respectively:

Interestingly, however, -eiss is incompatible with the potential -eci even though it can co-occur with the other usages of -eci. Recall from section 3 that intransitive verbs can only appear with potential -eci, not with passive -eci. Example (32a) is hence unambiguously a potential construction. As the ungrammaticality of (32b) demonstrates, the perfect marker -eiss cannot be attached to potential -eci.

Meanwhile, when -eci is suffixed to a transitive predicate and the by-Agent phrase is omitted as in (33a), the sentence is, as expected, ambiguous between potential and passive interpretations. Notice that when the perfect marker attaches to the verb as in (33b), the resulting sentence is only read as a passive construction.

In contrast to the compatibility between the perfect marker and the other three usages of -eci, the ungrammaticality of (32b) and unavailability of the potential reading in (33b) show that the potential construction built upon -eci does not contain any resultant state in its compositional meaning. Given our assumption in (13) that the same morpheme occupies the same syntactic head, we are then led to conclude that -eci is in charge of the ‘change’ semantics independent of ‘be’. That is, -eci is a realization of v GO (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015).

Because -eci, as v GO, simply introduces verbs of change, not including a result state, it is not required to accept the attachment of the marker expressing the continuation of a resultant state. It is not therefore surprising that the potential construction and the other three constructions exhibit diverging patterns when interacting with -eiss in (30)–(33).Footnote 16 Conversely, under an alternative hypothesis that -eci instantiates v BECOME (Harley Reference Harley1995), marking a ‘change of state’, -eci is expected to feed the perfect marker entailing a resultant state. In such an account, the ungrammaticality of (32b) and the unambiguity of (33b) are left unexplained.

Analyzing -eci as v GO, rather than v BECOME, offers a explanation for the morphological makeup of the derived change-of-state predicates like (34b). In Korean, some stative predicates have overt morphology realized by -ha, as in (16), repeated here as (34a). The suffix -eci can attach to these stative predicates to derive change-of-state predicates, as in (16b) and (34b). Under the classification of v flavours by Harley (Reference Harley1995, Reference Harley, Rooryck and Pica2002), the overt stative verbalizer -ha realizes the flavour v BE (H. K. Jung Reference Jung2016b, cf. D. Jung Reference Jung2002). Since -ha is responsible for marking the eventuality of ‘state’, it follows that -eci in (34b) corresponds to the ‘change’ eventuality. Treating -eci as v BECOME in (34b) would be a redundant marking of a result state because the be portion of be-come is independently expressed by -ha.

To sum up, the interaction between -eci and the perfect marker -eiss as well as the morphological patterns of the derived change-of-state verbs containing an overt stative marker are best captured if we analyze -eci as the marker of the eventuality of ‘change’ (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015), rather than ‘change of state’ (Harley Reference Harley1995, Marantz Reference Marantz, Dimitriadis, Siegel, Surek-Clark and Williams1997).

5. Passives and potential constructions: Voice or the lack thereof

5.1. The structure of passive and potential constructions

In section 4, I argued that the -eci suffix realizes the v GO head in Korean. Having identified the syntactic status of the morpheme, we are now in a position to consider the second question raised in section 3: the reason that passive and potential constructions formed with -eci display different syntactic behaviours. If -eci instantiates the same syntactic head v GO, what distinguishes the passive from the potential construction and gives rise to their syntactic distinctions?

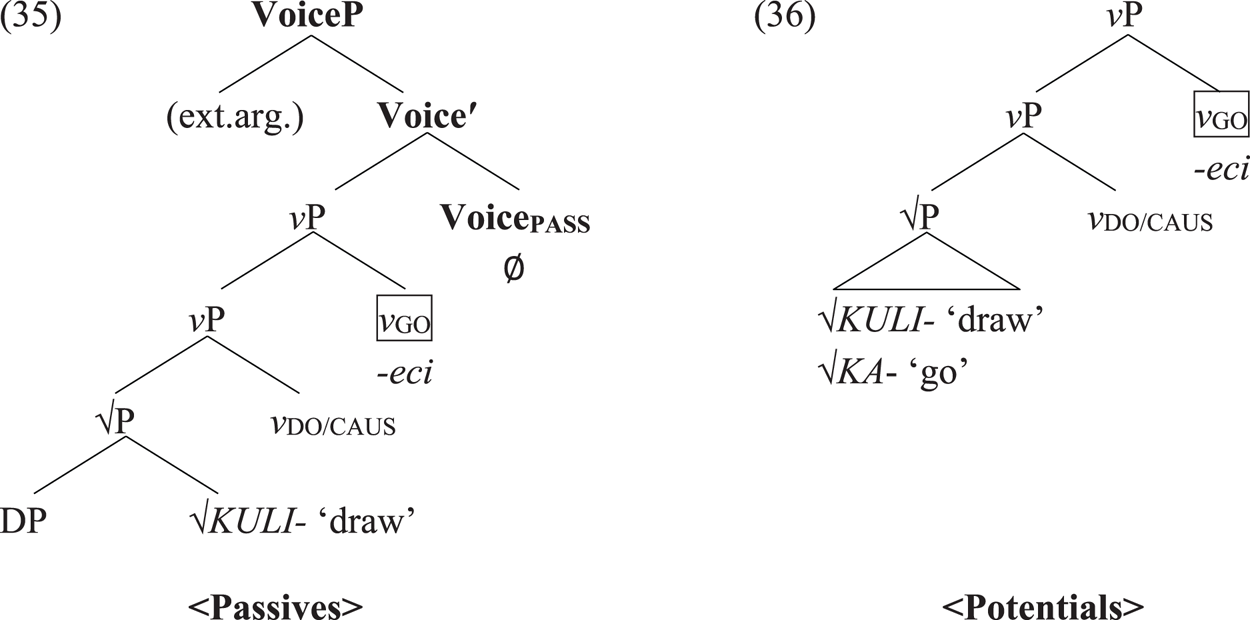

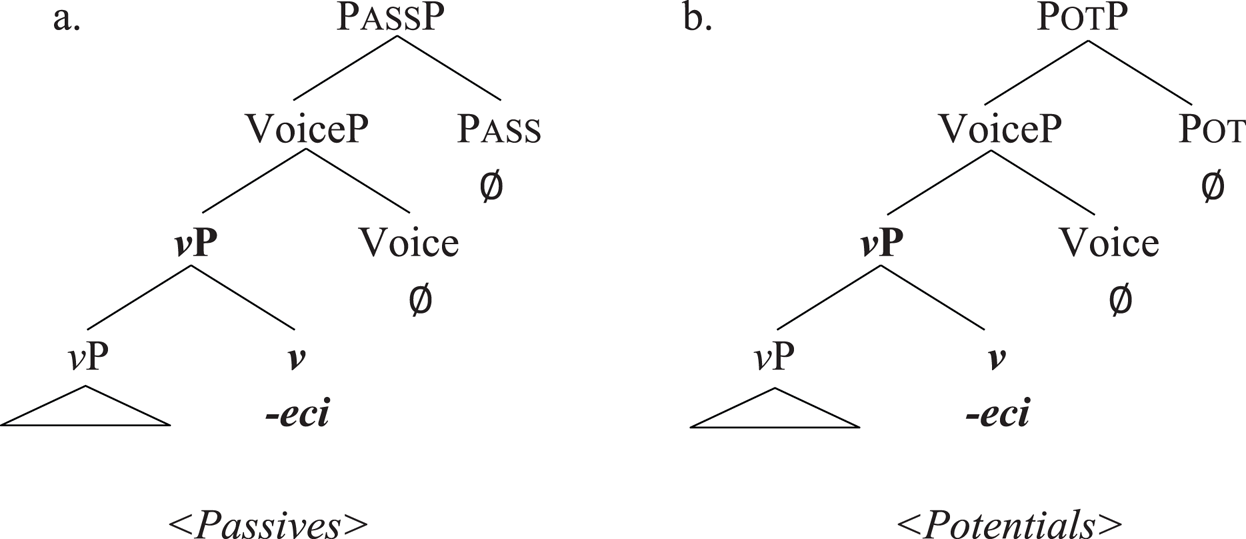

Lim (Reference Lim2015), extending Lim and Zubizarreta (Reference Lim, Zubizarreta, Demonte and McNally2012), proposes that the modal, or potential, -eci reading arises when the anticausative -eci configuration lacks an initiator of causation.Footnote 17 In a similar vein, Yeon (Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015) notes that in the potential -eci construction the Agent is suppressed, losing volitional control over the event. Building on Lim (Reference Lim2015) and Yeon's (Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015) insight, I argue that the distinct behaviours of the passive and potential constructions are attributable to the presence or absence of VoicePASS. In particular, while both passive and potential constructions formed with -eci share the substructure v GOP occupied by -eci, the two diverge in whether the derivation projects further into a VoicePASSP or not. I propose (35) for the structure of the passive -eci construction and (36) for that of the potential -eci construction:

Some remarks on the status and position of the implicit external argument in (35) are called for. Recall from our discussion in section 2.2 that Voice is a syntactic layer responsible for introducing an external argument, independent of v. I assume that VoiceACT(IVE) in (6) alternates with VoicePASS(IVE) in passives and that as a Voice head, VoicePASS also serves to host an external argument in its specifier. The difference between the two varieties of Voice would then be that the external argument associated with VoiceACT is overt, while that of VoicePASS can be covert. This assumption is derived by combining two conclusions from previous studies on the argument structure of passives. First, I follow Collins (Reference Collins2018) and Angelopoulous et al. (Reference Angelopoulos, Collins and Terzi2020) in treating the implicit external argument in passives in the form of by-Agent as a syntactic argument, just like its overt counterpart in actives.Footnote 18 Second, I adopt Harley (Reference Harley2013) and Hallman's (Reference Hallman2013) assumption that the verbalizing v DO/CAUS layer, with the indices do and caus, is responsible for semantically introducing the Agent/Causer role and that Voice satiates it syntactically. Specifically, because the verbalizing heads are distinguished by flavour, by the time v DO/CAUS enters into derivation, it indicates that the eventuality is an action/causation. This alludes to the semantic presence of an Agent/Causer role. A higher head, VoiceACT or VoicePASS, syntactically projects the argument in its specifier.

Regarding the first premise, Collins (Reference Collins2018) and Angelopoulos et al. (Reference Angelopoulos, Collins and Terzi2020) provide a convincing argument that the by-Agent in English and Greek passives is a genuine syntactic argument. Specifically, they show that unlike run-of-the-mill adjuncts, passive by-Agents are capable of binding a structurally lower element. By-Agents in Korean passives behave just like their English and Greek counterparts in that the DP of the by-phrase can bind the reflexive, as in (37). This is in sharp contrast to DPs inside obvious adjunct PPs in (38) and (39).Footnote 19

The binding capability of the passive by-Agent, which ordinary adjunct PPs lack, speaks for its status as a syntactic argument. I conclude, with Harley (Reference Harley2013) and Hallman (Reference Hallman2013), that a conceptually desirable candidate for hosting it is Voice in (35).Footnote 20

With all the ingredients in place, I now turn to two of the three observations discussed in section 3 regarding the diverging patterns between the potential and passive constructions:

(40) Observation 1: Potential -eci constructions reject modification by a by-Agent, whereas passives accept it (cf. (8), (11)–(12)).

(41) Observation 2: Passive -eci constructions can only be formed out of transitive verbs, while potential -eci can be attached to either transitive or intransitive predicates (cf. (8)–(10)).

The structural difference between (35) and (36) provides an immediate explanation for Observation 1 in (40). The passive structure includes a VoicePASS layer that hosts a covert external argument, as proposed in (35), whereas the potential structure lacks it, as in (36). Consequently, only passives allow the presence of the Agent argument in the form of a by-phrase. Potentials, which lack a VoiceP layer entirely, should not be compatible with a by-Agent.Footnote 21 As will be shown in section 5.2, this effect of the VoicePASS layer in allowing a by-Agent in passives, but prohibiting one in potentials, carries over to other conventional properties of implicit external arguments (Manzini Reference Manzini1983, Roeper Reference Roeper1987, Kallulli Reference Kallulli, Bonami and Hofherr2006).

With respect to Observation 2 in (41), it is worth noting that while the potential construction can be formed with intransitive predicates, it does not embed any intransitive. Compare the examples in (10), partially replicated in (42), with clear cases of unaccusative verbs, that is, verbs taking an inanimate Theme, in (43):

The contrast in the grammaticality in (42)–(43) demonstrates that the single argument of the verb appearing in the potential construction is understood to be a volitional entity — an Agent, by definition. In other words, potential -eci embeds unergatives. The eventuality that these predicates belong to is v DO, as depicted in the potential structure in (36).Footnote 22

Notice that in both the passive and potential structures, -eci selects v DO/CAUS complements. This ensures that unaccusative verbs (v GO), as a group, cannot appear in (35)–(36). Consequently, there are no passives of unaccusatives in Korean (fn. 27) and unaccusatives are not allowed in potentials either, ruling out (43).Footnote 23

Now let us return to Observation 2 in (41) — the restriction on passives to appear exclusively with transitives, in contrast to the relatively lenient selection made by potentials. Since the structure up to v GOP is identical between the passive and potential constructions in (35)–(36), it is reasonable to deduce that VoicePASS is responsible as well. Let us assume that VoicePASS has a requirement that can be satisfied by internally merging an internal argument — we can label it, for example, an uninterpretable [+Th(eme)] feature, without attaching any theoretical significance to the theta role itself. This yields the desired outcome. Since eventive unaccusatives are excluded for the independent reason given above, we are now concerned only with agentive transitives and unergatives. Specifically, in the passive structure in (35), the uninterpretable [+Th] feature of VoicePASS can be checked by a lower Theme DP if the agentive/causative root is transitive. With unergative roots, on the other hand, this [+Th] feature is left unchecked, causing the derivation to crash. By contrast, the potential structure in (36) lacks VoicePASS, along with its [+Th] requirement. As a consequence, whether the agentive/causative root is transitive or unergative is irrelevant to the well-formedness of the resulting structure. This correctly predicts that the potential construction can be produced with either transitive or unergative predicates.Footnote 24

A reviewer points out that this postulation of [+Th] on VoicePASS makes an interesting prediction. Specifically, verbs with an understood object like ‘eatvi’ should not be allowed in passives. This is because with no internal argument projected in syntax, these verbs cannot satisfy the [+Th] requirement of VoicePASS. In contrast, they should have no problem appearing in potentials, since potentials, lacking VoicePASS, do not care about the transitivity of the embedded predicate. As expected, when this subclass of verbs appear with -eci, they are unambiguously potential, not passive:

I have thus far argued that the presence or not of VoicePASS in the structure is responsible for the two phenomena in (40)–(41). In the subsection below, I present additional syntactic consequences that follow from this proposal.

5.2. Empirical consequences

The current proposal makes some additional predictions with respect to the implicit external argument introduced by VoicePASS. Specifically, the proposal predicts that the potential construction should fail in other traditional diagnostics for the presence of an implicit external argument (Manzini Reference Manzini1983, Roeper Reference Roeper1987, Kallulli Reference Kallulli, Bonami and Hofherr2006).

First, passives are cross-linguistically known to accept modification by agent-oriented adverbs, as in (45a). This is in sharp contrast to unaccusatives, as in (45b), which cannot be modified by agent-oriented adverbs. The different patterns between passives and unaccusatives in (45) are attributed to the presence of an implicit external argument in the former and the lack of it in the latter.

If potential constructions are syntactically free of the external argument by virtue of lacking Voice, as proposed in (36), we expect them to be incompatible with agent-oriented adverbs. This prediction is confirmed:

In contrast, we predict passive -eci to be able to occur with agent-oriented adverbs, just as with its English counterpart in (45a). This is because the passive structure in (35) involves the VoicePASS head licensing the implicit external argument, which in turn can be associated with the agent-oriented adverb. Korean passives behave as expected:

Recall (33a), in which the transitive predicate followed by -eci is ambiguous between passive and potential interpretations. If the current proposal is correct, adding uytocekulo ‘deliberately’ in such a sentence should ensure the passive reading, eliminating the potential reading. This prediction is borne out in (49):

Another relevant empirical domain is control. The understood Agent in passives is attested to be able to lead a control clause, as in (50a). This, however, is not allowed with unaccusatives like (50b). This contrast has traditionally been explained in terms of whether an implicit external argument is present (50a) or not (50b).

The present analysis predicts the potential -eci construction to be incapable of control. With no VoicePASS above -eci in the potential structure, there is no external argument to function as the controller of the embedded clause. This prediction is borne out:

In contrast, the passive -eci construction is expected to pattern just like its English counterpart in (50a) in allowing for an embedded control clause. This is confirmed in (52). The implicit external argument in (52) is understood to be the Agent argument of both the matrix predicate cosengha- ‘make’ and the embedded predicate cis- ‘build’:Footnote 25

To summarize, Korean potential and passive -eci constructions pattern exactly as the current proposal predicts with respect to agent-oriented adverbs and control. While passive and potential constructions share the v GOP headed by -eci, the presence/absence of the VoicePASS head results in their systematic syntactic contrasts.

5.3. vGO selecting another vP in passives and potentials

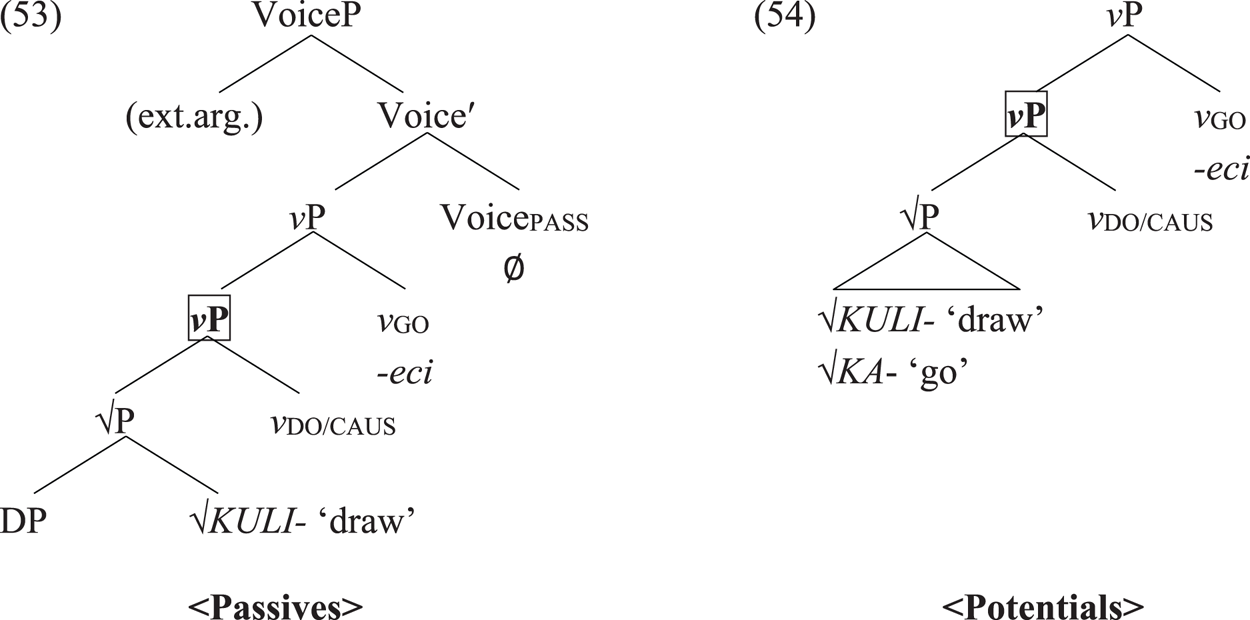

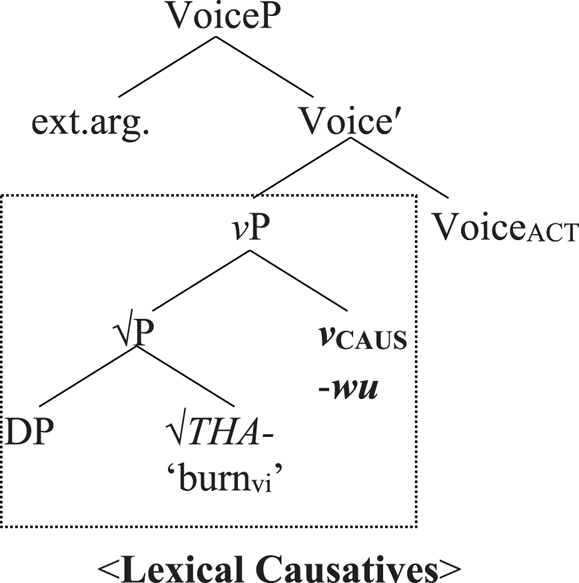

We have thus far focused on uncovering the category of -eci (section 4) and the syntactic head that selects it (or not) in the passive and potential structures (sections 5.1–2). In this subsection, I comment on the complement of -eci in these two constructions. The structures proposed for passives and potentials in (35)–(36) are repeated below as (53)–(54). Notably, in both (53) and (54), the v GO head realized by -eci selects a vP as its complement, rather than directly selecting for a √P:

Consider the alternation in (55). Based on the discussion in section 4.1, within the framework this paper adopts, lexical causative suffixes occupy the v position directly above the root (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Harley Reference Harley, Miyagawa and Saito2008; Miyagawa Reference Miyagawa, Schertz, Hogue, Bell, Brenner and Wray2011; H. K. Jung Reference Jung2014b). This means that the lexical causative suffix in (55b) is a realization of the first verbalizing head — v CAUS — taking an unaccusative root, as depicted below in (56).

(56)

Connecting this line of reasoning to the present proposal in (53)–(54), where the v GO realized by -eci selects a vP, we are led to predict that the v CAUSP marked by the dotted line in (56) is an eligible complement for the v GO in both passives and potentials. Morphologically, this means that both passive and potential -eci should be able to follow a lexical causative suffix. This prediction is confirmed in (57)–(58):

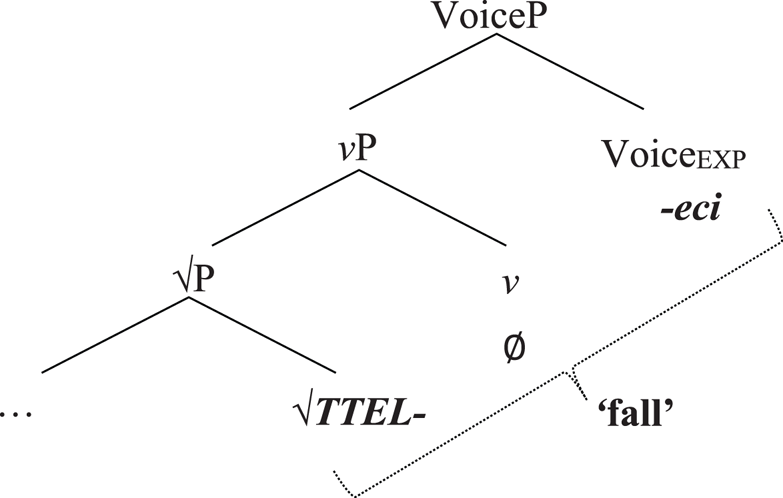

At this point let us revisit the lexical inchoative examples discussed in the (b) examples in (21)–(24). The sentence pair examined in (27) earlier is repeated below as (59):

It is worth reaffirming here that unlike the passive and potential -eci, the v GO in lexical inchoatives must appear immediately adjacent to the root. In other words, the v GO -eci in (59b) is root-selecting. This is because in the case of lexical inchoatives, the -eci suffix is the first verbalizer, as can be seen from the fact that the root on its own does not denote anything in (59a). Thus, in (59b), -eci completes the verb meaning as it assigns the root a category. This is what makes these limited set of roots cran morphemes.Footnote 26

Conversely, the meaning of the embedded predicate in both the potential and passive construction is readily identifiable. According to the proposal in (53)–(54), this property of passive/potential -eci, which distinguishes it from the -eci in lexical inchoatives, follows from the fact that -eci in (53)–(54) takes an already verbalized unit — namely, a vP — as its complement.

Thus far, I have argued for the first two claims posed at the outset of this paper — that (i) -eci is a phonological exponent for v GO in Korean and that (ii) the potential and passive constructions built upon -eci differ from each other in that the former lacks the functional head hosting the covert external argument in syntax, whereas the latter has it.

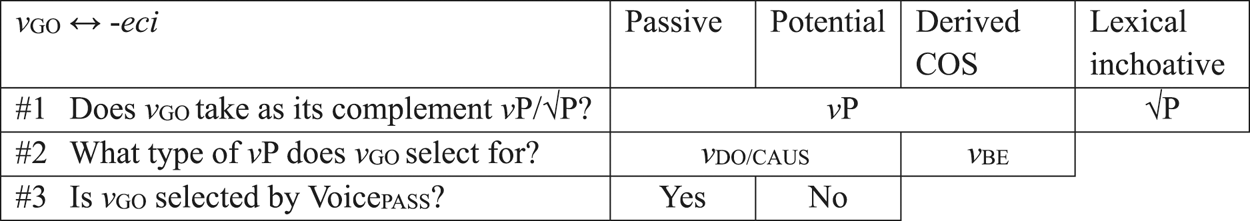

Based on the selectional properties associated with the v GO head, we can establish a set of diagnostics as in (60), which account for the -eci syncretism in Korean:

(60)

6. The potential semantics as a reflex of syntax

6.1. Potentiality as syntactic spontaneity

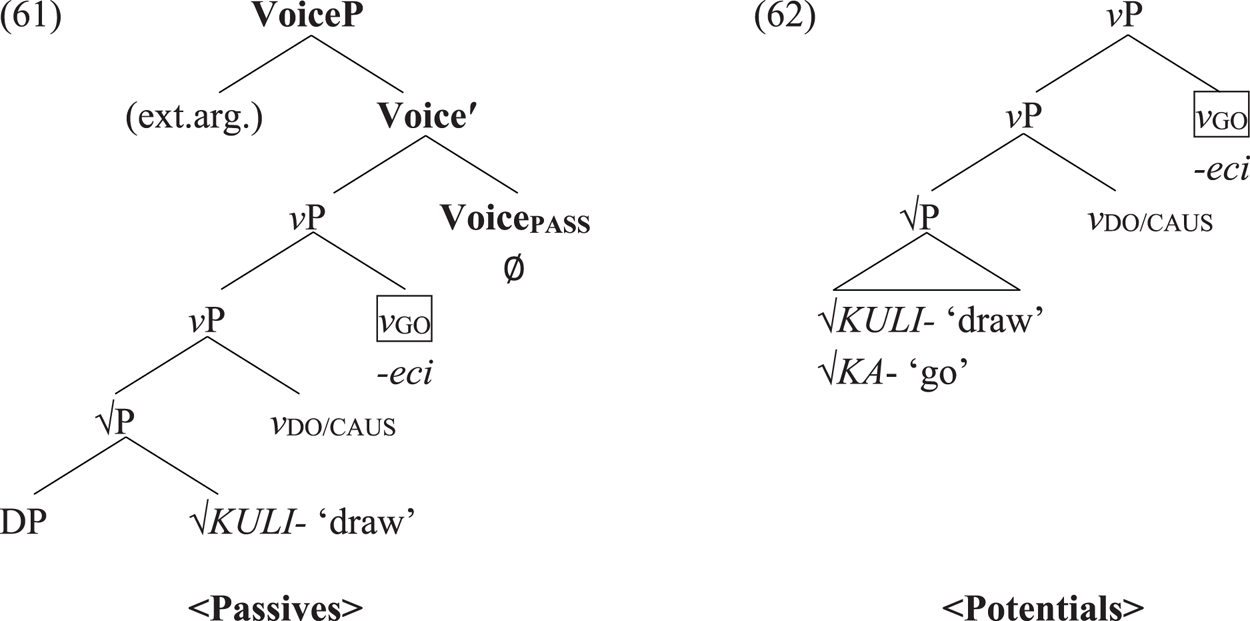

I have thus far argued that the presence or absence of VoicePASS in the structure results in the potential and passive constructions exhibiting a variety of different morpho-syntactic patterns. Having established the structural distinction between the two constructions, I now turn to my last question — what gives rise to the potential semantics, as distinguished from its passive counterpart? I propose that the key to the potential semantics is its syntactic composition. Specifically, it is invoked by the interplay among three structural factors in (36), repeated below as (62) — (i) the eventuality of v GO marked by -eci; (ii) the semantics of the selected v DO/CAUS; and (iii) the absence of the Voice layer.

An active agentive/causative verb in Korean is never marked with -eci. Under the present analysis, this means that once v GO is stacked on v DO/CAUSP, the resulting structure becomes either a passive or potential configuration. In the passive in (35), repeated here as (61), the covert argument introduced by VoicePASS is understood to be the Agent/Causer associated with the lower v DO/CAUSP and is responsible for the change event marked by v GOP. Compositionally, this yields the reading that an action/causation (i.e., v CAUS) has occurred (i.e., v GO) due to the external argument.

Conversely, there is no syntactic external argument that can be identified as the initiator of the v DO/CAUSP and that brings about the change marked by v GO in the potential structure in (62). Without a structural position to hold an external argument, there is no means of specifying “who” is responsible for the action/causation. The attention is thus on “what” happened — a change (i.e., v GO) leading to an action/causation (i.e., v DO/CAUS). This results in the understanding that something took place that made an action/causation possible, giving rise to the potentiality or possibility interpretation, translated here as ‘get/come to do X’.

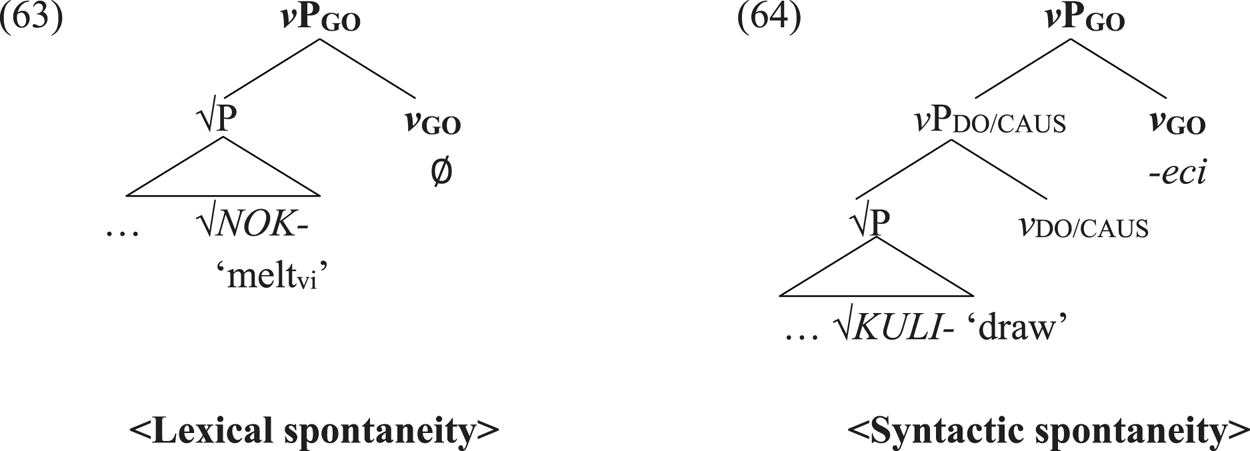

The semantic effect of not having an external argument in (62) is reminiscent of lexically-encoded spontaneous events expressed with inchoative verbs (e.g., nok- ‘meltvi’, tha- ‘burnvi’), where a change-of-state occurs with no external force, as expressed in (63). Cross-linguistically overt markers of spontaneity are observed to be attached to verbs whose lexical content is not inherently associated with spontaneous events (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath, Comrie and Polinsky1993, Reference Haspelmath2006; Schäfer Reference Schäfer2008; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015). Korean potentials can be understood in a similar vein. The suffix -eci, as the overt v GO marker, attaches to verbs of action/causation (i.e., v DO/CAUS), which are the least likely to be construed as spontaneous events.Footnote 27 Given that the interpretation of spontaneity in the potential structure is established above an already-verbalized unit (i.e., vP), as in (62) and (64), the potential structure can be understood to express ‘derived spontaneity’ or ‘syntactic spontaneity’.Footnote 28 This contrasts with the ‘lexical spontaneity’ expressed in (63), where the v GO head selects for the inchoative root. This implies that just as there are lexical and syntactic causatives, there is lexical and syntactic spontaneity. Importantly, both (63) and (64) involve an event of occurrence (i.e., v GO) and neither involves a structural external argument (i.e. the lexically spontaneous event in (63) due to the inherent property of the root, whereas the potential structure in (64) due to the fact that VoicePASS is left unmerged.)

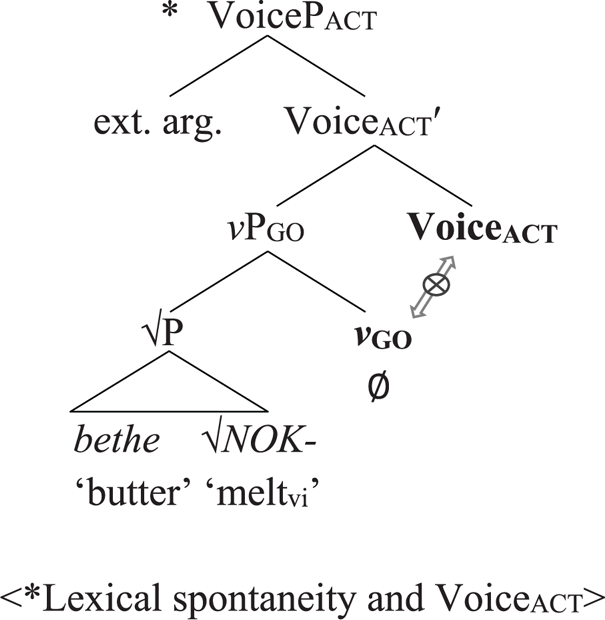

The proposal that -eci can participate in deriving spontaneity provides an explanation for the aforementioned observation that -eci is never found in active agentive/causative verbs. In particular, (65), where -eci follows a transitive verb in an active voice, is ungrammatical. According to the current assumption about the structure of verb phrases in section 2.2, in actives VoiceACT directly selects for the vP associated with the root, as in (66). The ungrammaticality of (65) with -eci can then be attributed to the restriction that the VoiceACT head cannot select for v GO, as represented in (67). What gives rise to such restriction?

I suggest that the incompatibility between the VoiceACT and -eci follows from the clash between the external argument of VoiceACT and the spontaneous events that the structure up to v GOP represents. In line with this idea, Cuervo's (Reference Cuervo2003) original insight is that the events that v GO characterizes lack a subject.Footnote 29 That is, lexically encoded spontaneous events associated with v GO are incompatible with an external argument that directly exerts force on the Theme argument. This is represented in (68). The Korean data in (69a) confirms this generalization. To express this kind of relationship in a transitive structure, v GO must be replaced with v CAUS, which is in turn selected by VoiceACT, as in (69b).Footnote 30 This yields a lexical causative structure, previously discussed in (56). To wit, lexically spontaneous events introduced by v GO cannot be directly selected by VoiceACT.

(68)

Now we can extend this reasoning to -eci, the overt exponence for v GO. Just as lexically-spontaneous events are incongruent with the external argument of VoiceACT, as in (68), we can posit that the spontaneity interpretation of potentials cannot be established with VoiceACT, as in (67). The unified account of v GO as part of spontaneous events provides a natural account of why -eci cannot be taken by VoiceACT.

Note, however, that while VoiceACT cannot select for -eci, VoicePASS can, producing the passive structure in (61). Thus, if v GO is not compatible with VoiceACT in connection to some property of the external argument that VoiceACT introduces, this implies that the sorts of external arguments introduced by VoiceACT and those by VoicePASS may not be homogenous.

As a full-scale investigation of this idea is beyond the scope of this study, I leave the matter open. However, I present some data that are consistent with this possibility. In Korean, active sentences tend to resist an indirect participant (Sichel Reference Sichel, Alexiadou and Rathert2010) as their external argument, as shown by the infelicity of (70a). To express the intended meaning, one opts for the passive counterpart in (70b):

Example (70a) is infelicitous because native speakers expect the subject of (70a) to be the entity that directly acts upon the Theme within the described eventuality. In other words, the external argument of VoiceACT is expected to be a direct participant, with the role of an Agent or a direct Cause. Silswu ‘a mistake’ in (70a), however, cannot be an appropriate subject because a mistake is not inherently capable of creating something, although it could be an indirect Cause for the creation.Footnote 31 In contrast, the set of external arguments hosted by VoicePASS is not limited to the role of Agent/direct Cause. Rather, it includes a wider range of external forces that either directly or indirectly promote a change (v GO) leading to the embedded event (v DO/CAUSP). As a result, the passive counterpart in (70b) allows an indirect Cause to be introduced by the postposition -ey uyhay ‘by’. The patterns observed in (70) suggest that the group of external arguments hosted by VoiceACT and that of VoicePASS are not identical, at least in Korean. I tentatively conclude that this distinction between VoiceACT and VoicePASS is correlated with their choice of complements, including their selectional relationship with -eci.Footnote 32

6.2. Unspecified external arguments and facilitators of potentiality

So far, I have shown that the potential and passive semantics results from the interplay of the respective syntactic heads involved. In so doing, the two non-active structures were distinguished from the structure with VoiceACT. The present analysis of the potential and passive constructions offers a refinement of Shibatani's (Reference Shibatani1985) notion of ‘Agent defocusing’. Shibatani unifies passives and passive-like constructions cross-linguistically under a prototype analysis, arguing that the key pragmatic function of passives and potentials is to defocus an Agent, not to promote the Theme (Perlmutter and Postal Reference Perlmutter, Postal, Whistler, Van Valin, Chiarello, Jaeger, Petruck, Thompson, Javkin and Woodbury1977). This commonality between passives and potentials led Yeon (Reference Yeon2003, Reference Yeon, Brown and Yeon2015) to subsume the potential -eci construction under the umbrella of passives. Passives and potentials diverge, however, in the extent to which agent defocusing applies. In passives, defocusing of an Agent takes place incompletely because the Agent can remain as an optional by-phrase. Other passive-like constructions that cannot express the logical subject, including potentials, are a consequence of having undergone complete defocusing of Agents.

This pragmatic concept can be embodied syntactically. Under the current analysis, agent defocusing can be explained by the substructure that the passive and potential constructions share. Essentially, agent defocusing is a consequence of not projecting VoiceACT on top of v DO/CAUSP, but instead v GO starting to take up the structure. Further projection of VoicePASS along with its implicit external argument gives rise to what Shibatani (Reference Shibatani1985) dubs “incomplete” defocusing in passives. “Complete” defocusing of Agents, on the other hand, corresponds to the lack of VoicePASS and the subsequent absence of the external argument in syntax entirely. In this sense, ‘agent defocusing’ can be viewed as a by-product of the derivation of v DO/CAUSP projecting on to v GO or further up to VoicePASS.

Taken together, the last observation made about (9)–(10), repeated below as (71), can be explained in light of the potential structure lacking VoicePASS in (36).

(71) Observation 3: Easily-type adverbs and the negative particle facilitate the potential interpretation.

Imagine a situation where a particular action/causation is carried out easily due to some reason not pertinent to the Agent/Causer. For example, the restaurant may have some pleasant feature that attracts customers in (10a). Wearing sneakers, instead of heels, makes running easy in (10b). These kinds of situation better match a syntactic structure where the Agent/Causer is unspecified — to the extent that it has no place in syntax, as in the potential structure in (36). Likewise, one could readily think of an opposite scenario where some obstacle, again not relevant to the Agent/Causer, hinders carrying out the action/causation. If a restaurant has got an unappealing property that keeps customers away in (10a), this could result in one's not going to the restaurant. The negative particle in combination with the potential construction delivers this meaning — a change (v GO) leading to the result of ‘not going to the restaurant’ (v DO). Notably, modifiers like ‘easily’ or the negative particle do not require syntactic absence of the external argument. They simply help build scenarios that are conducive to the potential semantics. These modifiers are therefore allowed in passives and actives as well.

To sum up, the absence of VoicePASS is the source of the semantic properties of the potential construction. With no syntactic external argument associated with a change leading to the downstairs agentive/causative event, the result is a spontaneous interpretation of ‘getting/coming to do X’. ‘Potential’ is thus a descriptive term for a syntactic structure where an eventuality of ‘change’ selects for another eventuality of ‘action/causation’, while syntactically not projecting the Agent/Causer argument.

7. Alternative analyses

In this section, I review alternative explanations of Korean -eci. These accounts share with the current proposal the principle of analyzing the affix syntactically in passives and other related constructions. However, they differ from the present account and from each other in their key assumptions. I show how this divergence leads to different, sometimes undesirable, empirical and conceptual consequences. Some of the alternatives could prove functional provided they adopt the conclusion of this study — that the -eci syncretism results from the suffix -eci realizing the same syntactic head v, separate from Voice.

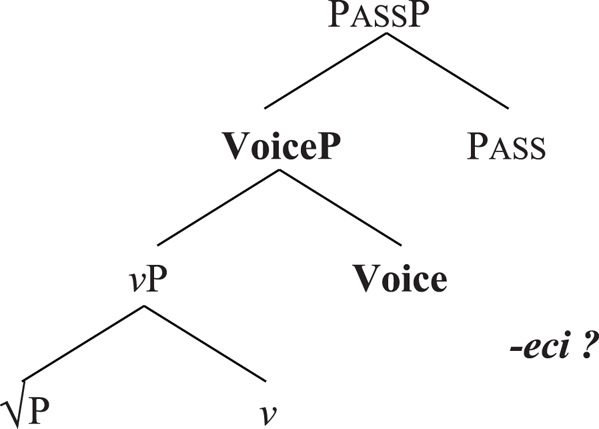

7.1. Passive -eci as v in the bipartite verbal system

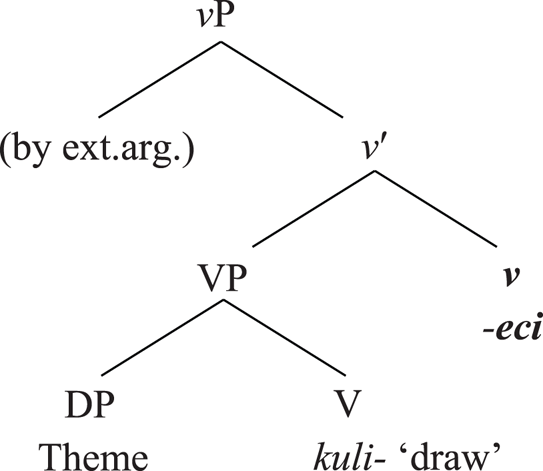

Earlier theoretical studies of Korean -eci largely concentrated on its occurrence in passives and were conducted within the traditional bipartite verbal configuration (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995, Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Zaring and Rooryck1996). Park and Whitman (Reference Park, Whitman and McClure2003) and S. D. Park (Reference Park2005) represent this line of thought. In particular, Park and Whitman (Reference Park, Whitman and McClure2003) treat -eci in the passive construction as an instance of the functional v above VP, as in (72).

(72)

In the passive structure in (72), -eci, as the passivizing morpheme, occupies the functional head introducing the implicit external argument. An immediate challenge for the structure in (72) is that it cannot be extended to other occurrences of -eci. Without additional machinery to explain why, unlike with passives, there is in this case no external argument involved in the potential, derived change-of-state, and lexical inchoative constructions, the structure in (72) cannot, by itself, provide a comprehensive account of all four constructions of -eci.

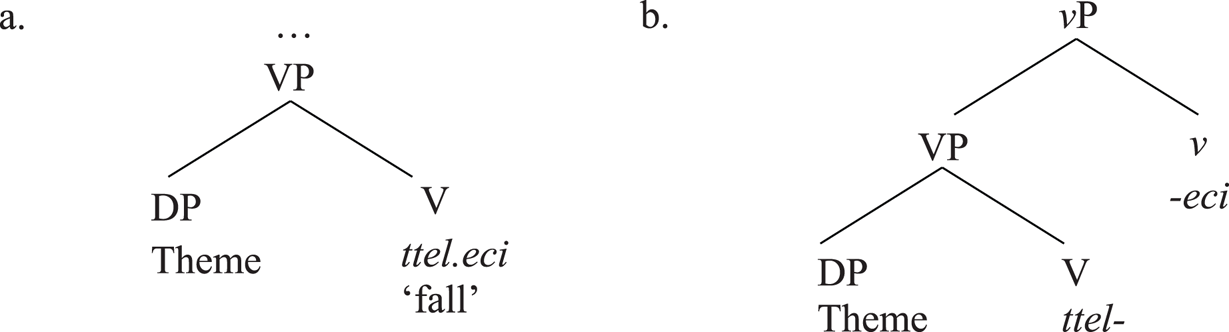

Park and Whitman's account cannot explain lexical inchoatives. As the analysis focuses on the passive usage of -eci, lexical inchoatives like ttel.eci- ‘fall’ would receive either of the two following treatments:

(73)

First, the suffix -eci could be taken to go under V together with the bound root ttel-, as in (73a). The option in (73a) faces a problem when compared with (72). Specifically, one is forced to conclude that passive -eci occupies v as in (72), whereas the same morpheme is part of V in (73a). An alternative would be to posit that the bound root ttel- goes under V and its -eci suffix under v, as in (73b). This creates yet another problem. Notice that in the bipartite structure such as (72)–(73), the downstairs predicate is labeled as V, meaning that it represents the syntactic category of verb. However, with a cran morpheme like ttel-, neither its meaning nor its category can be identified on its own. Thus, the structural representation in (73b), where the cran root ttel- is taken to be the lexical verb, cannot be an accurate representation of the data at issue.Footnote 33

In summary, alongside the vast cross-linguistic evidence that has triggered the paradigm shift to the tripartite verb structure (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006; Harley Reference Harley2013, Reference Harley, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017, among others), analyzing -eci as the v on top of lexical VP suffers from its own empirical issues. Under an analysis like (72), the syncretism exhibited by -eci is not handled systematically. We can thus conclude that a more intricate verbal structure is needed for an adequate syntactic account of the -eci syncretism.

7.2. Variants of Hypothesis 1

Recall Hypothesis 1, which is considered in (14a) and elaborated below, where I assumed -eci to occupy the Voice (passive) head in my previous studies (H. K. Jung Reference Jung2014a, Reference Jung2014b, Reference Jung2016a):

(74)

As discussed in section 4.1, while (74) may be consistent with the passive data in Korean, it cannot provide a comprehensive account of the environments where -eci occurs. With no further assumptions, (74) is inapplicable to derived change-of-state and lexical inchoative predicates, whose structure necessarily lacks an external argument. The various pieces of evidence presented in section 5 to explicate the potential structure provide further support for this conclusion. Specifically, the fact that the potential structure is incompatible with a by-Agent and agent-oriented adverbs and that the structure fails to control motivates an analysis of the potential structure where the VoicePASS head hosting the implicit external argument is missing entirely.

Note that this conclusion is only valid under the premise about the basic verb phrase adopted in section 2.2. Let us split the relevant portion of this premise into two parts:

(75) Assumption 1: A verb phrase basically consists of a category-neutral root, verbalizing v, and Voice.

(76) Assumption 2: Voice introduces a syntactic external argument.

For the “tripartite” system to work, the first assumption in (75) cannot be violated. This study has additionally assumed (76), where Voice is required to introduce a structural external argument, whether overt (i.e., VoiceACT) or covert (i.e., VoicePASS).

As previously mentioned in section 4.1, there are syntacticians who have taken a different perspective from (76) by allowing Voice not to introduce an external argument (Schäfer Reference Schäfer2008, Bruening Reference Bruening2012, Legate Reference Legate2014, Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015, Wood Reference Wood2015, Myler Reference Myler2016, Kastner Reference Kastner2020, Tyler Reference Tyler2020). Two different conceptions of Voice are relevant here — the unsaturated Voice head present in passives (and middles) (Bruening Reference Bruening2012) and the semantically expletive Voice (Schäfer Reference Schäfer2008, Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015). In this section, I reconnect the alternatives to the findings revealed in section 4 and show that regardless of one's theory of Voice, -eci cannot be the phonological exponence for Voice. The empirical challenges for these alternatives thus corroborate the proposal that -eci is a realization of v, marking the eventuality of ‘change’. However, if the present conclusion that -eci is v is adopted and some additional issues are dealt with, the hypotheses advancing specifier-less Voice can be extended to accommodate the passive and potential structures. I briefly sketch how below, turning first to introducing the two types of Voice with no specifier.

As pointed out by a reviewer, in an alternative approach to passives, the syntactically absent external argument is existentially quantified over (Bach Reference Bach1980, Keenan Reference Keenan, Teun, van der Hülst and Moortgat1980, Williams Reference Williams1987). Focusing on English passives, Bruening (Reference Bruening2012) argues for an analysis distinguishing semantic and syntactic requirements on Voice. Actives and passives involve the same Voice requiring an external argument. In actives, this requirement is satisfied by the conventional merging of the external argument in the specifier of Voice. In passives, the selectional feature of Voice remains unchecked until it combines with a higher head, Pass. As Pass checks off the selectional feature, it also saturates Voice by existentially closing over the external argument. This yields the existential reading that the action/causation described by the verb is performed by somebody when a by-phrase is omitted. Alternatively, when a by-phrase appears in passives, it attaches to Voice′ as an adjunct and specifies the external argument. Nonetheless, because by-phrase is an adjunct in Bruening's analysis, it cannot check off the selectional requirement of Voice for an external argument by itself. Pass takes the resulting VoiceP as its complement, simply checking off the selectional feature, but this time without existentially binding the external argument.

The head-final representation of passives of Bruening's analysis is offered in (77). Importantly, the Voice head in (77) is actually the active Voice, semantically not yet saturated (until it combines with Pass) and syntactically specifier-less. Notice also the single v layer below Voice. This v corresponds to the downstairs v DO/CAUS in the proposed passive structure in (35). Thus, (77) is missing the v GO layer, which the current analysis argues is the locus of -eci.

(77) Specifier-less Voice #1

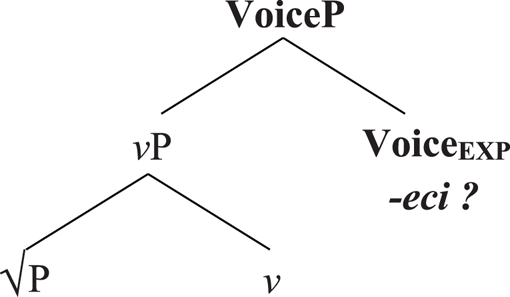

The passive structure in (77) cannot be directly applied to passives in Korean. Above all, the structure does not contain a syntactic projection that -eci can be inserted under. In Bruening's analysis, passives employ a single, active Voice head. However, as shown in section 6.1, -eci cannot appear with active Voice, meaning -eci cannot be the realization of an active Voice with no specifier. -eci cannot be Pass, either. Viewing -eci as Pass would render the other -eci constructions — potential, lexical inchoative, derived change of state — unexplained. The passive structure in (77) thus cannot adequately capture the Korean passive data.Footnote 34

The second type of Voice with no syntactic external argument is expletive Voice, VoiceEXP. In their seminal works on VoiceEXP, Schäfer (Reference Schäfer2008) and Alexiadou et al. (Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015) have argued that the Voice head can be semantically and/or syntactically active and/or inert, yielding four subtypes of Voice. Of these, VoiceEXP is both semantically and syntactically inactive, meaning that VoiceEXP not only lacks a specifier but also does not semantically entail the external argument. Nevertheless, VoiceEXP claims its place in syntax due to its morphological marking. Anticausatives in Greek are classified as belonging to this category. One might suggest that the consistent failure to detect the implicit argument in the potential construction (section 5) could be attributed to the semantically void nature of VoiceEXP and that -eci instantiates this VoiceEXP:

(78) Specifier-less Voice #2

However, the very evidence taken in section 4.1 to show that -eci is an exponence of the verbalizer introducing a ‘change’ serves as evidence against this possibility. First, the hypothesis in (78) would predict the following structure for lexical inchoatives, where -eci occupies VoiceEXP and its complement v is phonologically null:

(79)

The structure in (79) would correctly predict that ttel.eci ‘fall’ behaves as an unaccusative since VoiceEXP lacks the external argument both syntactically and semantically. However, with lexical inchoatives like ttel.eci, the root receives both its meaning and its category as verb after suffixation of -eci. This unique property of lexical inchoatives contradicts the representation in (79), where VoiceEXP is realized by -eci, instead of v, which, by hypothesis, assigns the root the category of verb.

In addition, the change-of-state predicates derived with -eci such as (15b) and (16b) pose another challenge. If -eci were to occupy VoiceEXP, the hypothetical structure of derived change-of-state verbs would be (80). This is in contrast to (81), which is the derived change-of-state structure formulated under the present analysis:

Again, the VoiceEXP structure in (80) is operational to the extent that it captures the unaccusativity of the resulting verb. However, unlike (81), where the compositional semantics of ‘become’ is attained via the two event markers v BE and v GO, the structure in (80) fails to capture the ‘change’ semantics in the derived change-of-state predicates. The empirical setbacks thus lead to the rejection of the alternative hypothesis in (78).Footnote 35

To summarize, -eci cannot be the realization of Voice in any of these alternatives presented. This reinforces the conclusion emphasized in this study — namely, that -eci is an instantiation of the verbalizing head v GO (Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015). This, however, is not to say that the patterns of -eci constructions refute the concept of specifier-less Voice itself. Under the present proposal that the passives and potential structures contain an additional vP projection headed by -eci, the specifier-less Voice account seems to explain the passive and potential data. An imperative corollary is that the Voice head above the v which -eci realizes is phonologically null. Below I outline how this plays out.

To begin with, null expletive VoiceEXP, being semantically and syntactically empty, could be additionally posited above the higher v head that -eci realizes in the proposed potential structure in (36). Under this approach, VoiceEXP could also be present in the lexical inchoative and derived change-of-state structures, as they are genuinely unaccusative. Unlike with anticausatives in Greek, however, postulating this in Korean would only serve a conceptual purpose because there is no morphological evidence.Footnote 36 At any rate, the two competing analyses — the potential structure advanced in (36), in which the Voice layer is missing entirely, and the alternative where a null VoiceEXP appears above -eci — make the same set of predictions with respect to the syntactic behaviors of potentials. Under this alternative, the differences between the passives and potentials would then be ascribed to the subtype of Voice involved, instead of the presence/absence of VoicePASS. A disadvantage of positing VoiceEXP in potentials, however, is that this cannot make sense of the fact that in potentials, the external argument is semantically entailed, though not syntactically (unlike in unaccusatives). As a reviewer points out, with the potential constructions in (9)–(10), we know that there is somebody who draws the picture or goes to the restaurant in the events described by the verb. Such an understanding does not follow from VoiceEXP.

Next, competing theories of Voice allow two additional ways to implement Voice that need not host a syntactic external argument. First, while maintaining the idea that Pass existentially closes over the external argument (Bruening Reference Bruening2012, Legate Reference Legate2014), as in (77), one could postulate a new null head, call it Pot, in place of Pass in the potential structure, with the resulting representations in (82). This Pot head, like Pass, would saturate Voice, and existentially quantify over the external argument. Importantly, however, Pot should not allow a by-Agent to saturate Voice. In this way Pot diverges from Pass: Pot requires that Voice have an open external argument.Footnote 37 Under this hypothesis then, the distinct syntactic heads — Pass and Pot — would be the source of the contrasting behaviors of potentials and passives.

(82)

Crucially, in order for this hypothesis to work with -eci, one cannot retain the stance that passives and actives contain the same Voice (Bruening Reference Bruening2012). This is because of the restriction that -eci never appears with active Voice (section 6.1). The analysis would thus need to conceive two distinct subcategories of Voice — one that projects a syntactic external argument (i.e., VoiceACT) and the other, say VoiceNON-ACT, with an open external role saturated by a higher head Pass/Pot. Without positing VoiceNON-ACT, nothing prevents an ill-formed structure where Voice in (82) takes the vP headed by -eci and, at the same time, merges with an overt external argument in its specifier, prior to merging with Pass/Pot. As a selecting head, the putative Pass/Pot in (82) demands that Voice not introduce a syntactic external argument to continue the derivation as a passive/potential. However, the newly added vP layer for -eci in (82) requires that the selectional relationship between Voice and v below it be constrained as well.

From a theoretical point of view, the core distinction between the diagrams in (82) and those proposed in (35)–(36) originates from one of the questions syntacticians have had as they try to reassign the traditional functions of v (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995, Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Zaring and Rooryck1996) to v and Voice. In particular, between v and Voice, which head is responsible for “semantically” encoding the external argument? In the present study, the semantic expression of the external argument is handled by v with the flavours do/caus. In (82), it is Voice. Voice introduces the semantic and/or syntactic external argument in Bruening's system. As a consequence, a more expanded VP structure is needed in (82).

Another way of employing a null Voice with no external argument is to make use of contextual allosemy (Wood Reference Wood2015, Myler Reference Myler2016). Contextual allosemy espouses the idea that Voice may have multiple allosemes, in which case they compete for insertion at LF, just as multiple allomorphs of a single morpheme do at PF. Information such as whether the external argument is semantically existent or not and, if so, which kind of external argument (e.g., Agent, Holder) needs to be interpreted, is determined by the contexts where Voice appears. In this model, the semantics associated with the external argument is delegated to LF.

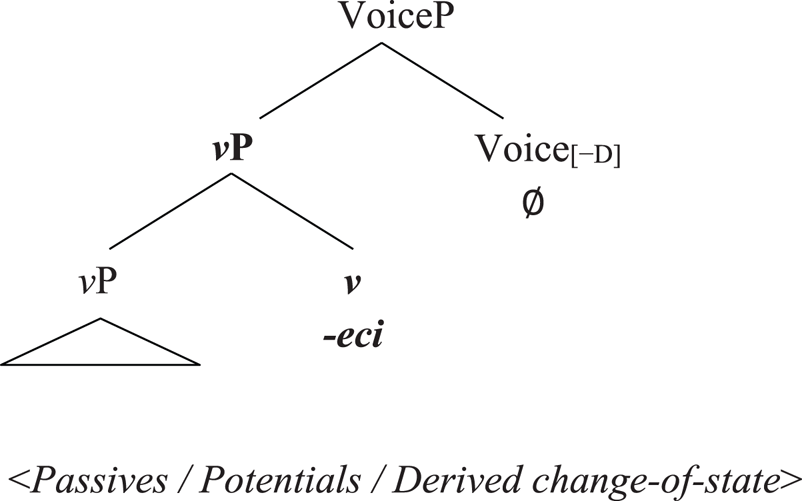

The trivalent theory of Voice advanced by Kastner (Reference Kastner2020) and Tyler (Reference Tyler2020) actively incorporates contextual allosemy. In addressing the intriguing Hebrew templates, Kastner (Reference Kastner2020) argues for a three-way classification of Voice — Voice[+D], which always projects a syntactic external argument; Voice[−D], which always lacks one; and unspecified Voice[ ], which may or may not host a syntactic external argument. Of these, Voice[−D] is relevant, since all of the -eci constructions are non-active in Kastner's sense.Footnote 38 Again, the spell-out for this Voice[−D] must be null, given that -eci is v.

These two ingredients — contextual allosemy and Voice[−D] — combined with the current finding that -eci is a verb-selecting v in passive and potential constructions, yield a single syntactic structure in (83). Without assuming v flavours, derived change-of-state verbs can also be subsumed in this structure, since -eci in these verbs selects for a vP complement too (see (60) and (81)).

(83)

With the configuration in (83), the Voice alloseme chosen singles out the relevant interpretation for the external argument. The choice of the Voice alloseme would be determined contextually with reference to the root. With Voice[−D] being the first phase, the roots should be able to influence Voice[−D] for interpretational purposes (Tyler Reference Tyler2020) across the two v's. The rules are roughly sketched out in (84), with the resulting construction marked in parentheses:

According to (84), transitive roots such as kuli- ‘draw’ are interpreted in association with an implicit Agent, yielding the passive reading. In contrast, other roots involve no Agent semantics. Depending on the particular root inserted, this either yields the potential or derived change-of-state constructions. Because kuli- ‘draw’ appear in both contexts in (84), the interpretation of the structure (83) when kuli- is inserted is correctly predicted to be ambiguous between passive and potential.

Notably, the set of rules in (84) does not acknowledge the “semantic” presence of the external argument in the potential construction. If, alternatively, the environment for potentials demanded a Voice alloseme with an implicit Agent, then the different behaviors of passives and potentials would be left unexplained. In addition, since the -eci in lexical inchoatives like ttel.eci- ‘fall’ is root-selecting, the structure in (83) does not apply to this subclass of -eci verbs. Consequently, lexical inchoatives are irrelevant in the competition depicted in (84).Footnote 39 This shows that while Voice allosemy is compatible with the Korean -eci data, it is not the underpinning mechanism that ties the four -eci constructions together.

So far I have outlined how three alternative theories of Voice — VoiceEXP, unsaturated Voice selected by Pass/Pot, and Voice allosemy — can be extended to accommodate Korean -eci passives and potentials (and at times the other -eci constructions), albeit with some remaining issues. Overall, the current analysis not only successfully explains the four -eci constructions but also has the unparalleled advantage that the syncretic nature of the -eci suffix follows naturally. Synthesizing the syntactic and morphological patterns of the constructions containing -eci, I conclude that -eci cannot be the exponent of v in the traditional split VP structure (section 7.1). Additionally, while the current set of Korean data can be handled by alternative accounts of Voice, they do not require these (section 7.2). Most of all, in order to adequately capture the morpho-syntax of the -eci constructions, any competing theory of Voice must be extended to reflect a highlight of the present study — that the -eci suffix instantiates v, not Voice.

8. Implications

Some implications follow from adopting the conclusions of this study. In particular, they shed light on the structural composition of unaccusative predicates and the typology of passives.

8.1. Unaccusative syntax

First, these findings constitute additional support for the split vP structure. Despite the shared substructure completed by the v GO head, the differences between passives and potentials arise due to the presence of an additional VoiceP level in the former and its absence in the latter. The distinct behaviours of the two constructions thus converge to corroborate a theory in which the verbalizing head and the Voice head are separated.

Additionally, the present proposal provides partial evidence that inchoativizing heads may behave in parallel with causativizing heads when it comes to complement selection. Specifically, within the last two decades syntacticians have shown that causativizing (i.e., v CAUS) heads have three complement choices — √P, another vP, and external-argument-introducing VoiceP (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Tubino-Blanco Reference Tubino-Blanco2011; Harley Reference Harley2013; Key Reference Key2013; H. K. Jung Reference Jung2014b, among others). I have shown here that v GO can directly select for a √P (in the case of lexical inchoatives) or take a vP complement (in passive, potential, and derived change-of-state constructions). This shows that the inchoativizing head mirrors its causativizing counterpart in its root- and vP-selecting properties. It remains to be seen whether v GO can also take a VoiceP complement, as with v CAUS, to complete the selectional pattern in both transitive and unaccusative configurations.

8.2. Passives

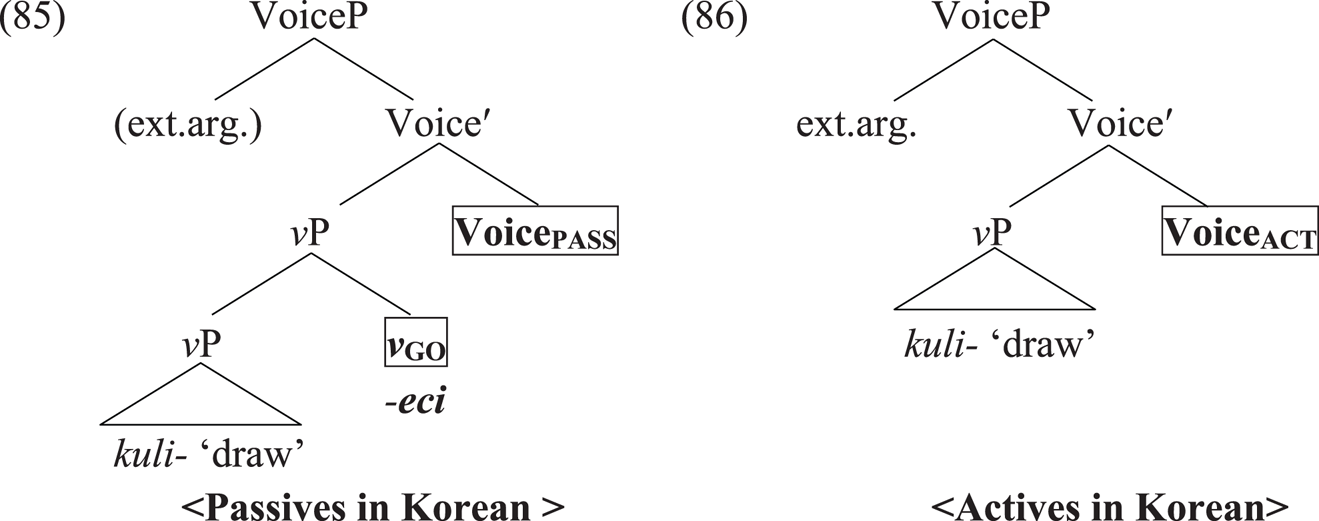

This proposal suggests a new understanding regarding the properties of passives. Korean passives formed with -eci conform to the universal tendencies of passives compiled in Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky2013). Particularly noteworthy is Kiparsky's generalization, originally owing to Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1990), that passives are always morphologically marked. In other words, no language marks actives and passives with the same morpheme. Let us consider how this statement connects to the passive structure in (85) and its active counterpart in (86):

In (85) and (86), the active and passive configurations share the substructure vP. Passive formation is completed by stacking two syntactic heads — v GO and VoicePASS — on the relevant vP (i.e., vPDO/CAUS), as in (85), whereas in the active structure in (86), a VoiceACT layer is added directly on top of vP. Since VoicePASS in (85) is morphologically null, the morphological marking of passives in the sense of Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky2013) is carried out by v GO.

Furthermore, with the two functional heads, v GO and VoicePASS, participating in the derivation of Korean passives, passives are not formed by the simple switching of VoiceACT to VoicePASS and subsequent movement of the Theme argument. I have shown that passivization is not semantically vacuous, at least in Korean. Given the role of v GO, passive formation involves marking the eventuality of ‘change’, in addition to the Voice alternation.

9. Conclusions

The syncretic morphology appearing in the four unaccusative configurations in Korean and their morpho-syntactic and semantic properties can be successfully captured with two independently motivated theoretical tools: (i) the intricate verbal structure consisting of root, verbalizing v, and Voice (Pylkkänen Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008; Cuervo Reference Cuervo2003, Reference Cuervo2014, Reference Cuervo2015; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou, Schäfer and Frascarelli2006; Harley Reference Harley2013, Reference Harley, D'Alessandro, Franco and Gallego2017, among others), and (ii) the assumption that morphological identity reflects syntactic identity (Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Anagnostopolou and Schäfer2015).