No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

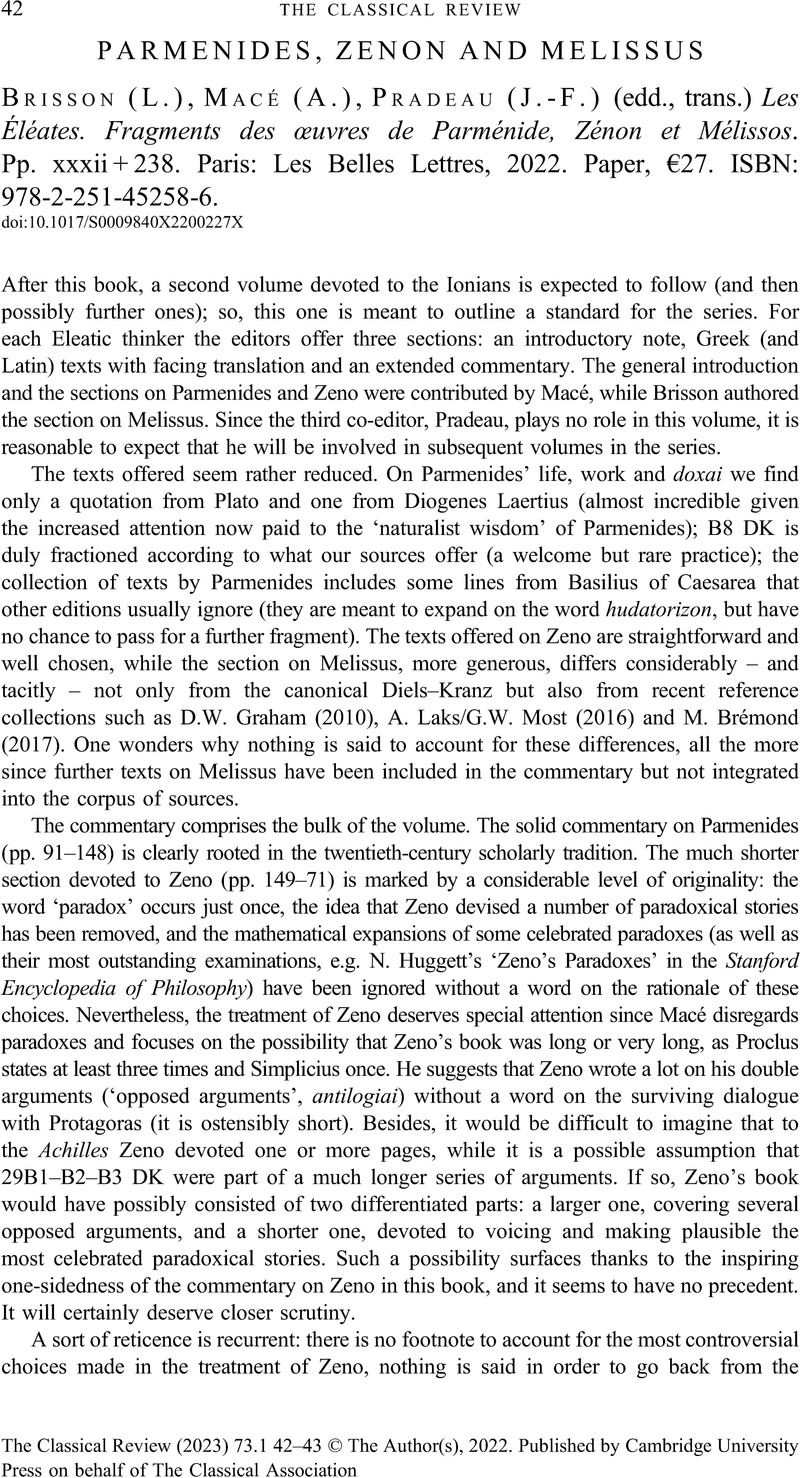

PARMENIDES, ZENON AND MELISSUS - (L.) Brisson, (A.) Macé, (J.-F.) Pradeau (edd., trans.) Les Éléates. Fragments des œuvres de Parménide, Zénon et Mélissos. Pp. xxxii + 238. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2022. Paper, €27. ISBN: 978-2-251-45258-6.

Review products

(L.) Brisson, (A.) Macé, (J.-F.) Pradeau (edd., trans.) Les Éléates. Fragments des œuvres de Parménide, Zénon et Mélissos. Pp. xxxii + 238. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2022. Paper, €27. ISBN: 978-2-251-45258-6.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 October 2022

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association