Cocos Malay, hereafter called Cocos, is referred to in the Ethnologue with the ISO code of ‘coa’. The Ethnologue considers Cocos to be a Malay-based Creole along with several other Malay-based creoles (Lewis Reference Lewis2009). Cocos is spoken in Australia and in Malaysia. In Australia, it is spoken on the islands of Cocos and Christmas with a total combined population of about 700 speakers on those two islands. In Malaysia, Cocos speakers are found primarily in the eastern and southeastern coastal districts of Sabah (Kunak, Semporna, Lahad Datu and Tawau). In early 2013, the Ethnologue listed the population of Cocos speakers in Malaysia as 4,000 and decreasing. The Ethnologue also stated that the total number of Cocos speakers in all places around the world is 5,000. However, both of these statements in the Ethnologue are not correct. The Cocos population in Malaysia is increasing, not decreasing, and the total worldwide population of Cocos speakers is much larger than the Ethnologue estimate. The 1970 population estimate for Cocos speakers in Malaysia was 2,731 (Moody Reference Moody1984: 93, 100). But the 2012 population estimate for Cocos speakers worldwide is 22,400, with most Cocos speakers living in Sabah, Malaysia.Footnote 1 Our study focused exclusively on Cocos speakers in Malaysia. Some Cocos speakers interviewed in our study claimed that their ancestors originated from the island of Cocos (also known as Keeling), southwest of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean. Others claimed that their ancestors originally inhabited the Indonesian islands of the Malay Archipelaɡo and subsequently migrated to Cocos Island and then to Sabah. Two historical accounts of the Cocos can be found in Nanis (Reference Nanis2011) and Subiah, Rabika & Kabul (Reference Subiah, Rabika, Kabul and Khoo1981).

There were no alternate names for this lanɡuaɡe in Enɡlish. But there were two alternate Malay lanɡuage spellings: Kokos and Kukus.

The ‘North Wind and the Sun’ text was translated and read by Adeka Bin Narel, aɡe 64 at the time of the recording. Mr Narel is fluent in both Cocos Malay and Standard Malay by his own admission. His wife is a Cocos speaker and they speak Cocos at home with their children and grandchildren. They all live in Kampung Cocos in the Lahad Datu district of Sabah, Malaysia.

This language community is not near any sound studio so the researcher had to produce these audio recordings in a remote section of a private school during a holiday.

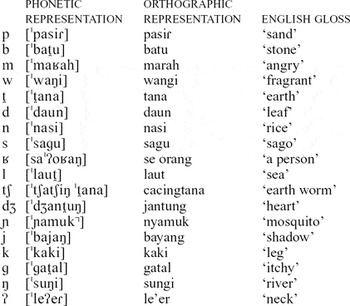

Consonants

The voiceless plosives /p/, /

![]() /, and /k/ are unaspirated, and they are unreleased in syllable-final position.

/, and /k/ are unaspirated, and they are unreleased in syllable-final position.

Cocos differs from standard Malay (Clynes & Deterdinɡ Reference Clynes and Deterding2011) and Indonesian (Soderberg & Olson Reference Soderberg and Olson2008) due to the presence of the uvular [ʁ]. The uvular [ʁ] always occurs intervocalically. The allophone of the uvular [ʁ], the flapped [ɾ], occurs syllable-finally, as in [ahiɾ-ɲa] ‘finally’ in the text in the final section of this paper. In the word-initial position, the uvular [ʁ] optionally deletes as in [ˈo

![]() an] ~ [ˈʁo

an] ~ [ˈʁo

![]() an] ‘rattan’.

an] ‘rattan’.

Secondly, Cocos differs from standard Malay and Indonesian regarding the [h]. The [h] is often deleted in Cocos. This is especially true in the word-initial position, as is shown in the following examples:

Word-initial [h]-deletion

The [h]was also deleted in word-medial and occasionally in word-final positions as the following examples demonstrate:

Word-medial and word-final [h]-deletion

However, word-final [h]-deletion is optional. For example, word-final [h] was optionally deleted with the word [ləˈbih] ~ [ləˈbi] ‘more’. But word-final [h] was not deleted with [ˈmaʁah] ‘angry’. Clynes & Deterding (Reference Clynes and Deterding2011) indicated that word-final [h] deletion showed variability as well in Brunei Malay.

Thirdly, some consonants, [f v ʃ z], which occur in standard Malay, at least in a marginal way, according to Clynes & Deterding (Reference Clynes and Deterding2011), do not occur in Cocos.

The glottal stop occurs in the following environments. First, it occurs as an allophone of /k/ syllable-finally, as in [ˈɲamuk˺ ~ ˈɲamuʔ] ‘mosquito’. Second, it occurs between identical or near identical vowels in some words such as [ˈleʔer] ‘neck’. Third, it occurs between a prefix ending in a vowel and a stem beginning with a vowel, irrespective of the vowel quality, e.g. [saˈʔoʁaŋ] ‘a person’.

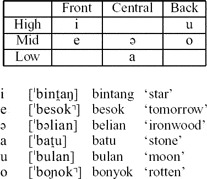

Vowels

Cocos has six vowel phonemes, /i e ə a o u/. But the vowels /i e o u/ generally lower to [ɪ ɛ ɔ ʊ] in a final closed syllable.

When the schwa, /ə/, occurs, it is not normally given prominence, and it is often elided. One example of elision occurred in line #2 of the recording with [səˈ

![]() udʒu] ~ [ˈs

udʒu] ~ [ˈs

![]() udʒu] ‘agree’.

udʒu] ‘agree’.

Vowel sequences

In standard Malay, vowel sequences occur root-finally in both open and closed syllables. However, vowel sequences in Cocos only occur in root-final closed syllables such as [ˈmain] ‘play’ and [ˈlau

![]() ] ‘sea’. They do not occur in root-final open syllables as the following examples illustrate:

] ‘sea’. They do not occur in root-final open syllables as the following examples illustrate:

Vowel sequences disappear in root-final open syllables

Root-final vowel sequences become single vowels in these open syllable environments. Interestingly, the Cocos vowel is not predictable from the Malay vowel sequence. The Malay words ending in [au] could transform into Cocos words ending with [o] as in [ˈpajo] ‘deer’ and [ˈpiso] ‘knife’. But this same Malay vowel sequence could also transform into Cocos words ending in [u], as in [ˈidʒu] ‘green’. Similarly, Malay words ending in [ai] could transform into Cocos words ending in [i], as in [ˈsuŋi] ‘river’, or could transform into Cocos words ending in [e], as in [ˈ

![]() ape] ‘rice wine’ or [ˈsampe] ‘until’.

ape] ‘rice wine’ or [ˈsampe] ‘until’.

Stress

Similar to Indonesian (Soderberg & Olson Reference Soderberg and Olson2008), stress in Cocos is predictable. Unaffixed words in isolation take primary stress on the penultimate syllable. But if the vowel in the penultimate syllable is a schwa /ə/, the stress is shifted to the ultimate syllable.

Stress examples

Transcription of recorded passage

ˈkapan ˈaŋin uˈ

![]() aʁa dan ma

aʁa dan ma

![]() ahaʁi /bəkaˈlaʔi ˈsapa ləˈbi ˈkua

ahaʁi /bəkaˈlaʔi ˈsapa ləˈbi ˈkua

![]() // ˈda

// ˈda

![]() aŋ sa ˈoʁaŋ pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa badʒuba // ˈdoʁaŋ ˈs

aŋ sa ˈoʁaŋ pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa badʒuba // ˈdoʁaŋ ˈs

![]() udʒu ˈsapa ˈbisa ˈbua

udʒu ˈsapa ˈbisa ˈbua

![]() pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

![]() u ˈbuka dʒuˈbaɲa / diˈkiʁa / ləˈbi ˈandal // ləˈpas ˈi

u ˈbuka dʒuˈbaɲa / diˈkiʁa / ləˈbi ˈandal // ləˈpas ˈi

![]() u / ˈaŋin uˈ

u / ˈaŋin uˈ

![]() aʁa maˈniup saˈkua

aʁa maˈniup saˈkua

![]() ˈkua

ˈkua

![]() ɲa// ˈ

ɲa// ˈ

![]() api ˈmaŋkin ˈkua

api ˈmaŋkin ˈkua

![]() ˈaŋin baˈ

ˈaŋin baˈ

![]() iup / ˈmaŋkin ˈdəka

iup / ˈmaŋkin ˈdəka

![]() pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

![]() u ˈpeɡaŋ dʒuˈbaɲa / ˈsampe ahiɾɲa / ˈaŋin uˈ

u ˈpeɡaŋ dʒuˈbaɲa / ˈsampe ahiɾɲa / ˈaŋin uˈ

![]() aʁa ˈakun ˈkala //

aʁa ˈakun ˈkala //

![]() ʁus ma

ʁus ma

![]() aˈhaʁi dipanˈtʃaɾkan / siˈnaɾɲa dan

aˈhaʁi dipanˈtʃaɾkan / siˈnaɾɲa dan

![]() ʁus pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

ʁus pəŋɡəmˈbaʁa ˈi

![]() u ˈbuka dʒuˈbaɲa / ˈsampe ˈaŋin uˈ

u ˈbuka dʒuˈbaɲa / ˈsampe ˈaŋin uˈ

![]() aʁa

aʁa

![]() əˈpaksa ˈakun ˈbawa ma

əˈpaksa ˈakun ˈbawa ma

![]() ahaʁi ləˈbi ˈkua

ahaʁi ləˈbi ˈkua

![]() //

//

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Haji Daud Amatzin, Datuk Hj Light Nanis, Margaret Hartzler, two anonymous JIPA reviewers and JIPA editor, Adrian Simpson, for their helpful comments and suggestions. All errors are my responsibility.