INTRODUCTION

The Throne Room at Knossos and its painted decoration are one of the most celebrated, yet highly contentious, topics of discussion in Aegean archaeology. Previous bibliography is marred by substantial confusion and misunderstanding stemming from a significant amount of imaginative speculation that has been piled over the years on top of Arthur Evans's Throne Room reconstructions. The latter are in themselves highly suspect and dependent on Evans's own firm ideas about the nature of Knossian society, its religion and symbolism.

The recent redevelopment of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and of the Archaeological Museum in Herakleion presented us with an excellent opportunity to re-examine the painted fragments discovered by Evans and his team in the Throne Room in 1900. It allowed us to retrace their excavation and to bring together the extant archival data, stored in Oxford, and the archaeological remains, housed at Herakleion, in an effort to identify the painted fragments that today can be attributed safely to the Knossian Throne Room. The conservation of some of the fragments, in preparation for their display at Herakleion, has helped clarify further the decorative programme of the Throne Room and of the paint layers and techniques used in its decoration.

For archaeological and stylistic reasons, discussed below, a Late Minoan (LM) II date is favoured for the execution of the Throne Room's decorative programme, which included ‘traditional’ (i.e. Neopalatial) and ‘innovative’ (i.e. Final Palatial) elements. The coexistence of these elements is, in our view, best interpreted as a conscious effort of the artist(s) and their commissioners to create a new, yet still recognisable, image of power – an image that represents an artistic as well as a political turning point between the Neopalatial and Final Palatial periods. Within this context, the Throne Room's decorative programme can be understood as part and parcel of a new, emerging, ideology – one that was based on the transformation and subversion of material culture, and of images in particular.

THE EXCAVATION OF THE THRONE ROOM AT KNOSSOS

The painted fragments that form the focus of our study were discovered by Arthur Evans and his team, under the direction of Duncan Mackenzie, between 11 and 18 April 1900 in the palace at Knossos and more specifically in the ‘Throne Room’, a space also referred to in the original excavation notebooks as the ‘bath chamber’, ‘bath room’ or ‘room of [the] throne’ (Figs 1, 2, 3).Footnote 1 On 12 April 1900, at a depth of about 30 cm from the surface and almost in the middle of the north wall, there came to light the ‘fresco with tree’ (DM/DB 1900.1, 13 April, 34) – one of the largest wall paintings to be discovered in situ at the site (Fig. 4): ‘The N. wall of the bath room was brought partially into view near the surface and [a] wall painting, surmounted by a plain dado, began to appear with design resembling the branches of a palm tree’ (DM/DB 1900.1, 12 April, 24–5). More fragments came to light on 14 April on the north side of the west wall, showing ‘grey palms’ on a hilly ‘red ground’, with some fragments clearly having fallen out of place (DM/DB 1900.1, 14 April, 37–8). In the next few days it transpired that paintings of a decorative character adorned the room's north-east corner and north and west walls but not the area of the ‘bath chamber’ proper, where only horizontal bands decorated the upper part of the red-painted walls.

Fig. 1. Excavating the Throne Room at Knossos, 12 April 1900. PhEvans Book 8, 21, no. E.Top. 655 (= Evans Reference Evans1935, fig. 881). Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

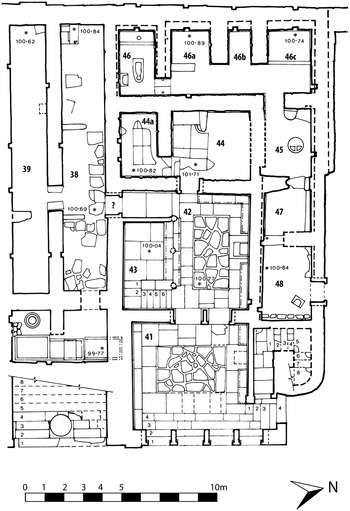

Fig. 2. Plan of the ground floor, West Wing, Throne Room complex, Palace at Knossos. Adapted by the authors from Hood Reference Hood1981, ground plan. Note that the distance between throne and benches is not accurate (i.e. shorter in this drawing than it actually is [c.80 cm]). Courtesy of the British School at Athens.

Fig. 3. Plan of the Throne Room proper (rooms 41–44) in LM II. Benches indicated in light grey. It is not certain that the dithyron shown in Fig. 2 (between room 42 and room 41) corresponds to an ancient reality. The available data are not sufficient and we cannot at present tie the dithyron to the reconstruction of Period III. Numbers in white indicate walls with painted decoration on them. By the authors.

Fig. 4. The throne with the ‘palm fresco’ in situ, 1900. PhEvans Book 8, 19, no. E.Top. 664b (= Evans Reference Evans1935, fig. 889 trimmed). Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

The lifting of more painted fragments by Yannis Papadakis, from either side of the door in the west wall of the Throne Room, coincided on 18 April with a visit to Knossos by Emile Gilliéron, père, who was to become Evans's chief artist for the Knossos excavations, specialising in the restoration of the paintings. Gilliéron was the first to recognise the existence of a ‘griffin in part of [the] bath-room fresco’ (AE/NB 1900, 18 April, 48). His identification immediately convinced Evans, who noted in his diary that ‘it now becomes clear that a guardian griffin stood on either side of the door leading to the room beyond the bath chamber’ (AE/NB 1900, 18 April, 48–9).

This is all the information we have from the original notebooks kept by Evans and Mackenzie at the time of excavation with regard to the painted fragments discovered in the Throne Room at Knossos. With the help of the excavation photographs and the section drawings by Theodore Fyfe – Evans's first architect at Knossos – we can now attempt to piece together what was actually found in April 1900.

PAINTED FRAGMENTS ATTRIBUTABLE TO THE THRONE ROOM

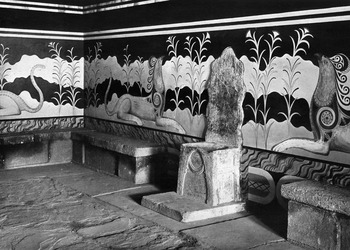

Since the 1960s, it has become clear that the extensive reconstructions of the Gilliérons, father and son, in the Throne Room at Knossos blended elements from various painted fragments and created a decorative programme which, as it currently stands, never existed (Hopkins Reference Hopkins1963; Palmer Reference Palmer1969, 35–7). The first partial reconstruction of 1913 (Fig. 5) combined elements from fragments belonging to all three walls of the Throne Room, including the ‘fresco with tree’ (e.g. the ‘altar’ and the animal's front paw). This partial reconstruction on the west side of the north wall – the area that yielded the fewest painted fragments – then became the prototype for the completion of the room's decoration in 1930. As a result, visitors to the Throne Room continue to admire to this day the work of the Gilliérons (Fig. 6), which bears little resemblance to the original fragments found in 1900. Most recently, in 2002–4, and as part of the conservation, consolidation and enhancement of the palace, the work of the Gilliérons was conserved anew (Tsitsa and Lakirdakidou Reference Tsitsa, Lakirdakidou and Minos2008).

Fig. 5. The 1913 reconstruction of the west part of the Throne Room's north wall. PhEvans Book 8, 20, no. E.Top. 2394. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 6. The 1930 reconstruction of the Throne Room's north wall. PhEvans Book 8, 24, no. E.Top. 656c (= Brown Reference Brown2000, fig. 22c). Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

In identifying the painted fragments found in the course of excavation in the Throne Room, we have numbered the areas where they appear from ‘1’ to ‘6’, starting with the north-east wall (Fig. 3):

-

1 – north-east wall (corner): the lower part of the wall decoration is still in situ, though poorly preserved. The whereabouts of the upper part are unknown. Several archival photographs and drawings exist illustrating the painted fragments as found (Figs 7–8). Original dimensions: W: c.90 cm × H: 152 cm. Archival and excavation references: AE/NB 1900, 14 April, 38 and KnDrA II.B/1 and B/2 f–g (details of plants from north-east wall; probably by Theodore Fyfe).

The painted fragments on the north-east wall show four plants with dark blue-grey stems and leaves with red flowers. The two tall ones in the middle look more like papyrus–reed hybrids, what Evans first identified as ‘sedges or rushes’. They were perhaps similar to the other papyrus–reed plants found elsewhere in the room. The other two plants, on either side of the two taller plants, probably depicted some kind of fern or hybridised papyrus–lotus. They are similar to the ‘waz’ (papyrus) motif on the shoulder of the best-preserved griffin from the south part of the west wall (more below). Similar plants and ‘flowers’ appear on both parts of the west wall. The undulating bands follow the room's general scheme and may add some weight to the idea of a balanced composition in the Throne Room, an idea to which we return below. Part of the ‘veined stone’ dado decoration was preserved under the lowermost undulating band.

Fig. 7. Plants, undulating bands and part of the ‘veined stone’ from the north-east wall of the Throne Room. Pencil and watercolour on tracing paper. Probably Theodore Fyfe, c.1900–1. KnDrA II.B/2 g. W: 98 cm × H: 103 cm. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 8. Theodore Fyfe's drawing (1901) showing fragments of fresco as found on the north and east walls of the Throne Room (KnDrA I.WW/8). Here only two sections are shown: ‘section on line AA’, which refers to the section from west to east (looking north), and ‘section on line CC’, which refers to the section from north to south (looking east). W: 43 cm × H: 57 cm (of complete drawing). Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

-

2 – north wall, east part, abutting on the throne: ‘fresco with tree’ or ‘palm fresco’. On permanent exhibition in gallery 13 in the Archaeological Museum at Herakleion. Max H: 163 cm × max W: 80 cm. Excavation and archival references: AE/NB 1900, 13 April, 32; DM/DB 1900.1, April 12–14, 24–5 and 32–8; KnDrA I.WW/8 (Fig. 8), and numerous archival photographs.

In his first report, Evans (Reference Evans1899–1900, 40) mentions that ‘at one point rises a palm tree’, without, however, specifying the exact position of the palm within the walls of the Throne Room and without describing it in detail. In The Palace of Minos, no discussion of this particular fresco was ever included (cf. Evans Reference Evans1921, 253–4; 1928, 493–9; 1935, 901–46, esp. 905–20), despite the fact that the excavation photos clearly show its position and subject matter (Evans Reference Evans1935, 906, fig. 881, and 915, fig. 889; also Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 111–12, pl. 129).

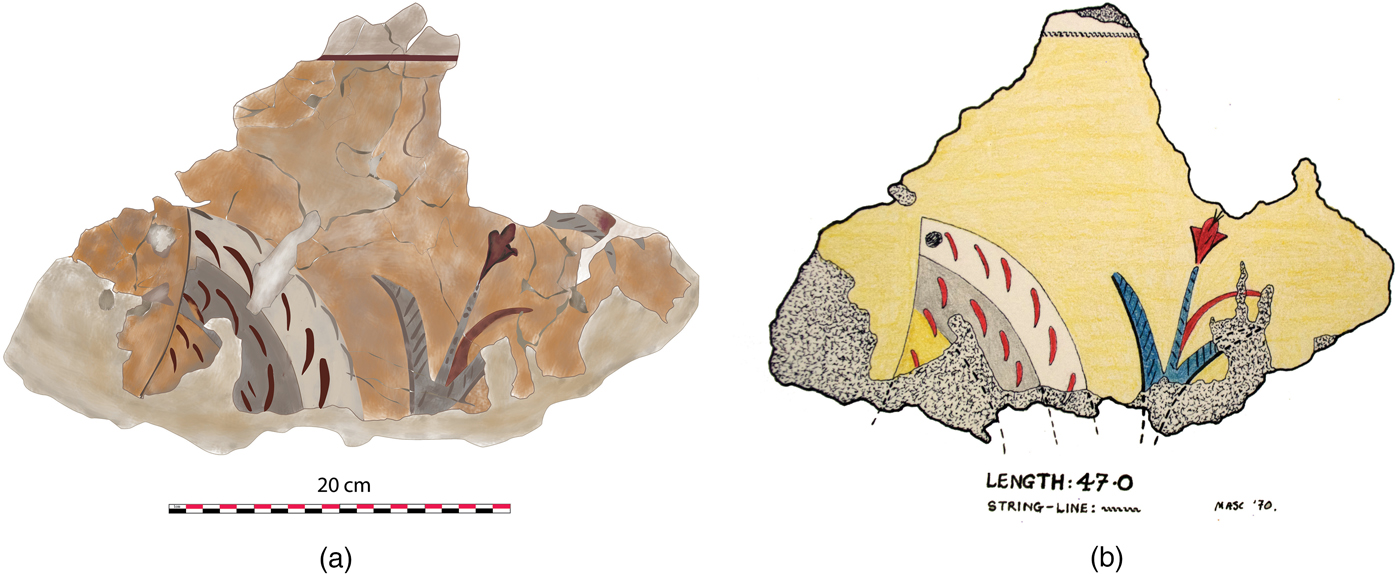

It was only in the late 1960s that a detailed macroscopic analysis was carried out by Mark Cameron (Fig. 9), who included it in his doctoral dissertation (Cameron Reference Cameron1970; Reference Cameron1976; Reference Cameron, Hägg and Marinatos1987).Footnote 2 Along with the work of Evans and the Gilliérons, Cameron's study has significantly influenced all successive attempts to reconstruct and interpret the composition on the north wall and the Throne Room as a whole. Although his work remains outstanding, Cameron based his study of this painting on the unconserved fragments, with all the problems that lack of conservation entails, especially with regard to details and colours. At the same time, he does not appear to have consulted the archival material stored at the Ashmolean. His work records, stored in the British School at Athens (e.g. CAM 178–81, CAM 211, CAM 235, CAM 262, CAM 270, CAM 382, CAM 476, CAM 523), reveal his extensive study of this fresco which he planned to publish – something that unfortunately never materialised, perhaps also due to his untimely death.

This large fragment has four curved indentations on the upper-left side, where it abutted the back of the throne, and is straight in the lower left side, where the plaster abutted the seat (Figs 10, 11). The upper part and left side are incomplete but part of the base appears to have met the floor, judging also by Fyfe's 1900 section drawing (Fig. 8) and the excavation photographs at the Ashmolean Museum. A close examination of the archival records actually suggests that the fragment discovered by Evans was originally about 20 per cent larger than the fragment preserved today in the Herakleion Museum (Fig. 12). The largest loss is observed on the upper right corner, where according to archival information another group of three leaves was preserved at the time of excavation. This section, as suggested by the available photographs,Footnote 3 probably fell off the wall – and was most likely destroyed – sometime in 1900, i.e. prior to the detachment of the ‘palm fresco’.

In terms of decoration, this fragment is divided into an upper and a lower part. The upper part is dominated by a dark-red palm with a large rounded base which springs ‘diagonally upwards from the left edge at the junction of pictorial field and dado’ (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 111). A closer examination of the rendering of the red trunk of the tree reveals considerable variation in colour, which begins with clear ochre and ends in dark red (Figs 11, 13). The transition from one colour to another was achieved through the application of red on ochre (in the form of a solid line and of red dots). An auburn line runs along the right side of the tree's trunk, with the latter set very close to the actual stone seat without, however, ‘touching’ it. The colour difference between the red leaves and their red background is achieved through the use of different tones of red – light red for the leaves and dark red for the background – as well as ‘impasto’ white dots for the outline of the leaves (Fig. 13). The use of ‘impasto’ decoration – already observed by Cameron (Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 111–12) – allows us to detect the presence of red leaves on a red background even when the preservation of one or the other is not good (for the use of ‘impasto’ in Aegean painting, see Cameron, Jones and Philippakis Reference Cameron, Jones and Philippakis1977, 159, 165, 168, and Brysbaert Reference Brysbaert2008, 117, fig. 6:7).

Despite some partial loss since 1900, the archival evidence – photographs and Fyfe's section drawing – helps us to ascertain securely that the palm originally had at least two pairs of three leaves on either side. It may have been crowned with a single large leaf set along the axis of the trunk, as suggested by Cameron in his reconstruction drawing (Cameron Reference Cameron, Hägg and Marinatos1987, fig. 3 and fig. 7), though nothing remains of this part today (Fig. 11).Footnote 4 The three lower leaves on the left side of the trunk end up on the throne's edge, thus ‘touching’ it. The recent conservation of this fragment, as part of our study and for its display in the redeveloped Herakleion Museum, revealed the presence of fruits (dates) on the central part of the tree (Figs 11, 14). Each fruit is indicated by three white ‘impasto’ dots. Most of them are oval in shape, which corresponds to the drupe of the Phoenix theophrasti palm.Footnote 5

Conservation and Raman spectroscopy have also helped to clarify the background arrangement on the upper part of this fresco: in total, four undulating bands (each between 20 and 22 cm in height) were observed. They alternate between white (or light grey) and dark red. This arrangement, which is securely documented on the painted fragments from the west wall, is also attested in the north-east corner mentioned above. Contrary to Cameron (Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 197; 1987) and subsequent reconstructions that considered this feature a mistake of the 1930 restoration, the four undulating bands actually form the most secure element of the Evans-Gilliéron reconstruction. Although spectroscopy in spots nos 2, 3, 4 and 16 (Fig. 15) did not conclusively prove the existence of a red undulating band in the uppermost left part of the fragment abutting to the throne (e.g. no clear traces of hematite [Fe2O3] were identified), macroscopic observation appears to suggest that here too the background colour was red. The persistence of the ancient artist(s) in maintaining the four undulating bands may also explain what looks like a rather odd choice, i.e. to represent the red leaves of the palm against a red background.Footnote 6

To the right of the palm an animal's paw is visible (four toenails, one flaked away). Originally, it was identified by Evans as belonging to an ‘eel’, which he thought appropriate for a riverine landscape, based on his interpretation of the four undulating bands as representing hills and flowing rivers (Evans Reference Evans1899–1900, 40). However, soon after the discovery of the west wall of the Throne Room, which yielded the two best-preserved griffins, Evans decided to interpret it as the front paw of a griffin (Evans Reference Evans1899–1900, 39–40).Footnote 7 In collaboration with the Gilliérons, Evans used the paw from the ‘palm fresco’ in the reconstruction of the best-preserved griffins on the west wall of the Throne Room, especially the one from the south part of the west wall, i.e. the griffin facing right towards the entrance to the so-called ‘inner sanctuary’Footnote 8 (KnDrA II.B/2a-I = Evans Reference Evans1935, fig. 884 and fig. 894).

Although no front paws are actually preserved on the two griffins framing the door to the ‘inner sanctuary’, the skin colour of the beast's paw in the ‘palm fresco’ is the same as that on the best-preserved griffin on the south part of the west wall. This skin colour convention is suggestive to us that here too we are dealing with a griffin. Moreover, similarities observed in the rendering of the paw (to indicate hair texture and depth) and the hind leg of the best-preserved griffin add further support to the view that the beast to the right of the palm was indeed a couchant griffin.

Between the upper and lower parts of the ‘palm fresco’, there are two horizontal, though not entirely straight, incised lines drawn with a sharp tool. These incisions offered guidance for the planning of the painted surface. They were drawn while the surface was still damp, suggesting that the palm fragment should, in principle, be considered a fresco (Brysbaert Reference Brysbaert2008, 113 and 116, who also stresses that these lines would make more sense when a ‘buon fresco’ is planned than a ‘secco’ painting). The reason that a sharp instrument might have been preferred here – and only on that spot, judging by the other extant fragments – might be due to the effort of the ancient artist(s) to align these two lines to the nearby throne, since its back could have posed some problems standing out from the surrounding plaster, and with the bench so close they may indeed have decided to go ‘freehand’. In the ‘palm fresco’, the artist(s) may have used the lowermost level of the back of the throne, just above the seat, as the guide for the upper incised line; the latter sits immediately under the tree and paw of the animal. The actual level of the seat, before it starts getting hollow, was used as the guide for the lowermost incised line, just above the ‘veined stone’ dado.

In the lower part, and immediately under the horizontal lines, we find part of the ‘veined stone’ dado decoration which is featured on all the walls in the Throne Room where figural painting appears. The conservation has helped bring to light the impressive colour gradation of the ‘veined stone’ decoration. The artist(s), having already placed the basic colours (red, brown-red, grey-black and ochre), used a brush to briskly pass a layer of impasto-lime over the ‘veins’ (wavy lines). The result is the creation of a strong pink (white on red) and yellow tint (white on ochre; for the use of red [hematite: Fe2O3] see Fig. 15:14).

Within the dado, and surrounded on three sides by ‘veined stone’ decoration, we find the ‘altar-base’: contrary to all existing reconstruction drawings (e.g. Evans Reference Evans1935, pl. XXXII, 911, fig. 884 and 919–20, fig. 894), the white impasto band outlining the ‘altar’ does not run all the way to the edge of the ‘veined stone’ imitation, but stops almost midway. In this respect, the shape of the incurved structure clearly echoes that of ‘altar-bases’ in Neopalatial and Final Palatial representations. While slender versions of the ‘altar’ do occur in LM IA/LC I wall painting (e.g. on the wooden ‘doors’ of the ‘tree-shrine’ depicted on the east wall of the lustral basin in Xeste 3 at Akrotiri: Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008, 496, fig. 41:10), the ‘cut-out’ style applied in the rendering of this object in the ‘palm fresco’ is unprecedented in Minoan wall painting at that time.Footnote 9 Placed against a horizontal band, the ‘altar’ in the ‘palm fresco’ recalls the line-up of load-bearing incurved bases in front of a triple red horizontal band in the wall painting of the ‘Seated Goddess’ in Xeste 3 at Akrotiri. The use of lattice pattern as a filling motif in the white horizontal band on both sides of the ‘altar’ in the Throne Room fresco has no parallels in Minoan art, though the pattern itself is well known from wall painting and seal imagery (more below).

For the lowermost pieces of this fresco, now resembling a grey band, Evans and Cameron were convinced that colours were obscured by fire (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 112 with earlier references). Our examination suggests that the deformation in the lowermost part of the fresco is a result of humidity and fungal infection, which developed on its surface over the course of time. The excellent colour preservation (e.g. of the ‘veined stone’) further reinforces, in our view, this idea. This is not to say that the palace was not burned down, but that our examination did not detect any traces of fire on the wall paintings from the Throne Room.

A small fragment above the ‘palm fresco’ can be seen in the archival photographs (estimated L: 25 cm × estimated H: 15 cm). It included part of the lowermost register of three bands (‘frieze lines’ according to Fyfe): white for the lowermost band, followed by red in the middle and most likely off-white/grey for the uppermost (Figs 5, 12). This fragment formed part of the lowermost zone of bands decorating the upper part of the north wall. Fyfe used this piece, along with similar fragments on the west wall and the lustral basin,Footnote 10 as his guide for the reconstruction of the room's original height.Footnote 11 In situ until 1930, the present location of this fragment is unknown.

Fig. 9. The north wall of the Throne Room as reconstructed by Mark Cameron. Courtesy of the Mark Cameron Papers (CAM 523), British School at Athens.

Fig. 10. Stages of conservation of the ‘palm fresco’: (a) prior to conservation, (b) in the course of conservation, (c) post-conservation. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

Fig. 11. Drawing by Pepi Stefanaki reproducing the current state of the ‘palm fresco’ following its conservation. Courtesy of Yannis Galanakis and Pepi Stefanaki.

Fig. 12. The conserved ‘palm fresco’ set against Fyfe's original architectural drawing; about 20% of the fresco found on the north wall is no longer preserved. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 13. A detail from the ‘palm fresco’ showing part of the veined dado, the base of the tree trunk, the animal's paw and the red leaves with ‘impasto’ outline set against a dark-red background. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

Fig. 14. The dates (white dots digitally enhanced for clarity) on the palm tree. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

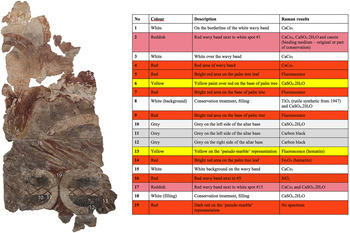

Fig. 15. Summary of the results of the Raman micro-spectroscopy study carried out on the ‘palm fresco’ by A. Philippidis, P. Siozos, K. Melessanaki and D. Anglos of the IESL-FORTH with assistance from E. Tsitsa and Y. Galanakis. A mobile Raman micro-spectrometer (HE 785, JY Horiba) was used to study 19 spots (nos 1–19). The beam was focused on the sample surface through a microscope objective lens that illuminated an area of diameter around 50 µm. The beam power on the sample was in the range 0.05–5.5 mW. Typical exposure time was 20 sec per scan, while 10 scans were averaged. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

-

3 – north wall, west part (Fig. 16): a relatively large fragment with ‘veined stone’ dado decoration just above the bench shown in Fyfe's 1900 section drawing. The current whereabouts of this fragment are unknown. Estimated L: 120 cm × max H: 25 cm. Archival reference: KnDrA I.WW/8. No reference is made to this fragment in the excavation notebooks.

This is the only painted fragment that we can securely assign to the west side of the throne. The ‘veins’ are moving in the other direction from those on the ‘palm fresco’. It remained on the wall after the removal of the latter, as suggested by a photo now at the Ashmolean Museum (PhEvans Book 8, 33, no. E.Top. 2398). It had already been removed during the decoration of the west part of the north wall by the Gilliérons in 1913. A fragment from this fresco may have turned up in 1973 (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 196, who notes that the Gilliérons reversed the direction of the wavy lines in the dado on either side of the throne).

Theodore Fyfe's architectural drawing clearly illustrates the painted fragments as found on the north wall of the Throne Room at Knossos (Fig. 8): the ‘palm fresco’ and a band fragment on the east side of the throne, as well as part of the ‘veined stone’ dado decoration on the west side. The section drawing, along with the excavation notebooks and archival photographs, makes it clear that we have no evidence for the presence of a griffin or an ‘altar’ on the west side of the throne as assumed by Evans, the Gilliérons and Cameron and all reconstructions ever since (a smudge visible to the west of the throne on Fig. 8 is exactly that – just ink, not a painted fragment). The ‘symmetry and aesthetic balance’ in the design and overall composition of the Throne Room (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 197) is therefore conjectural and needs to be explained rather than taken for granted – a point that we develop further below.

Fig. 16. North wall fragments juxtaposed onto Fyfe's drawing. Prepared by and courtesy of Ute Günkel-Maschek.

-

4 – west wall, north part (Figs 17, 18): panel with painted fragments (in storage in the Archaeological Museum at Herakleion). Dimensions of panel: W: 231 cm × H: 140 cm. Archival and excavation references: AE/NB 1900, 14 April, 38; DM/NB 1900.1, 14 April, 37–8; a reconstructed, left-facing griffin on the north part of the west wall appears in two of Fyfe's drawings that later formed the basis of Lambert's 1917 drawing of the reconstructed Throne Room, KnDrA II.B/4–5 (esp. B4a drawn in 1901) and Evans Reference Evans1935, frontispiece (pl. XXXIII); fragments from this part of the west wall are visible en masse in several archival photographs: e.g. PhEvans, Book 8, 33, no. E.Top. 2223 and 34, no. E.Top. 678c; also Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 98 and 110–11, pls 111d and 128.

This panel was studied in detail by Elizabeth Shank as part of her doctoral dissertation (Shank Reference Shank2003; also Shank and Balas Reference Shank, Balas, Foster and Laffineur2003; Shank Reference Shank, Nelson, Williams and Betancourt2007). It consists of more than 30 fragments which can be grouped in 23 pieces as identified in Fig. 17 a. Most of them relate to the decoration of the north part of the west wall (e.g. nos 1–9, 15–21) and a good number can also be reconstructed with some certainty (Fig. 17 b:1). No ‘veined stone’ dado decoration is preserved among the fragments. However, as this pattern is attested in the north-east corner, on either side of the throne on the north wall, and in the south part of the west wall, we believe that this feature also appeared on the north part of the west wall.

Based on the available fragments, a left-facing griffin can be identified, the chest of which bears a very close resemblance to that of the right-facing griffin on the west wall on the other side of the door. In front of this couchant griffin there are three papyrus–reed hybrids (same as on the south part of the west wall) (Fig. 19). The whole scene is set against four undulating bands, alternating between off-white and red. Above the undulating bands, there are two registers of horizontal bands. The lowermost register consists of three bands (white, red, and off-white/grey, from bottom to top). Two thin red-coloured bands contour the lowermost white band and two narrow white bands contour the off-white/grey band. The uppermost register has a similar arrangement but the width of the bands appears to be slightly different. Although not much remains of the griffin or the floral decoration, the extant fragments from the north part of the west wall (including the beast's tail, Fig. 17 a:18–19, and part of the vegetation, Fig. 17 a:17, Fig. 17 a:19–20) appear to be identical to that on the south part of the west wall, further reinforcing the presence of a balanced composition on either side of the door leading to the ‘inner sanctuary’.

The single most important fragment, from the north part of the west wall, is undoubtedly the ‘crest’ that can be seen at the bottom of fragment no. 7, first identified by Shank (Shank and Balas Reference Shank, Balas, Foster and Laffineur2003, 163, pl. XLIb). In one of her reconstructions, Shank placed this fragment on the north wall of the Throne Room (Shank Reference Shank, Nelson, Williams and Betancourt2007, 164, fig. 19:4, as a crest, and fig. 19:5, as a wingtip). Yet there is no evidence that this piece ever belonged there. Instead, a close study of the archival photographs suggests to us that this fragment can actually be identified among the in situ remains on the north part of the west wall (Fig. 18 inset is identified because of its breaks as part of Fig. 17 a:7, a fragment which in 1900 was still clinging on the wall). Moreover, this piece comes from the area where the third from bottom white undulating band meets the fourth and final red undulating band. Therefore, this fragment would fit perfectly with the griffin on the north part of the west wall as a raised crest (as suggested in our reconstruction: Fig. 17 b:1).Footnote 12

As part of this panel, there are also some painted fragments that do not appear to belong to this wall (Figs 17 a, 17 b:2–3). They differ from the other fragments from the north part of the west wall in that the background colour, where pictorial representation appears, is ochre not red (e.g. Fig. 17 a:10, 22–3); and that the middle horizontal band is painted in ochre instead of red (e.g. Fig. 17 a:11, 13). In addition to these differences, the outer edges of the horizontal bands associated with the light ochre fragments were painted (Fig. 17 b:2), not incised as those of the main composition (Fig. 17 b:1) which could further suggest that some of these fragments come from another – perhaps very similar – decorative programme, but not from the Throne Room proper.Footnote 13 The top end of a ‘flower’ is visible in no. 10, while again the most important piece appears to be the ‘crest’ set on a light ochre background (Fig. 17 a:22). From the few details available to us, this ‘crest’ – almost identical in rendering and overall layout to the two crests on the north and south part of the west wall – along with the bands and floral decoration may have belonged to a similar scene (i.e. a crested griffin set in a similarly rendered floral environment).

Cameron was the first to identify no. 22 as a ‘crest’ (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, 111; CAM 235, Fig. 20). He considered it part of the griffin on the east side of the throne (Fig. 9). He placed this fragment on the north wall because he thought that its background would find a better match there than on the west wall, where the upper undulating band is clearly red. He was of the opinion that the background – the undulating bands – somehow changed colour round the north-west corner of the Throne Room: ‘for that reason’, he noted, ‘I have added ex hypothesi large palm trees at the W and E sides of the northern frieze so that the ‘changeover’ in background scheme can be distinguished’, which explains the addition of more palm trees in his reconstruction (letter from Mark Cameron to Sieglinde Mirié, 4 March 1972; Mark Cameron Papers, British School at Athens). If, however, the uppermost undulating band on the ‘palm fresco’ is red also on the north wall, as we argue here, then this fragment would fit neither on the north nor on the two parts of the west wall (Fig. 21).

Admittedly, we do not know where the fragments with a light ochre background come from. We should not exclude the possibility that the ‘crest’ identified by Cameron actually comes from another floor or area of the palace, where a similar decoration appeared, and that it was included in the fragments from the north part of the west wall by mistake. A letter by Mackenzie to Evans (dated 17 November 1901) may provide us with a clue as to how these fragments were packed for transportation to the Herakleion Museum in the way they were (i.e. not always correctly): ‘it became clear that there was not much use trying to fit more pieces at Knossos, and all that could be done was to take care that, in packing, pieces that belonged together should at least go into one box, if possible into one layer. So all the fresco was sent to the museum’ (letter cited in Momigliano Reference Momigliano1999, 159). Since the unconserved fragments from the north part of the west wall had already been removed in the course of the 1900–1 season, as suggested by the available archival photographs, it becomes clear that pieces that belonged together, or were thought to have belonged together, were stored in the same panel. The collection and storing of these fragments should thus make us extremely cautious when trying to associate the fragments with ochre background with the walls of the Throne Room. Similar decorative schemes may indeed have been present on the walls of different rooms at the same time at Knossos. We can infer this from the left-facing chest fragment of a griffin, said to be from the palace, with an almost identical design to the griffins from the Throne Room (Cameron Reference Cameron1976, 112, pl. 130A).

The available archival images show numerous details now no longer preserved on the extant fragments (Fig. 18). We estimate that about 30 per cent of the fragments found in situ on the north part of the west wall are now lost (e.g. the plants on the right side of the composition are still visible in the early excavation photos for 1900 but not in the later ones of that year [e.g. PhEvans Book 8, 22, no. E.Top. 656]). Some of these lost fragments were included in Fyfe's 1901 coloured reconstruction of the Throne Room (KnDrA II.B/4 = Fig. 22), which was subsequently used as the basis for Lambert's 1917 drawing (KnDrA II.B4a = Fig. 23). Mackenzie noted in his diary: ‘the fallen fresco of the W wall showed a design of palms on a hilly ground. At the top were double grey bands at large intervals in grey on the red ground. The palms were grey on the red ground’ (DM/DB 1900.1, 14 April, 38). Although not ‘palms’ as Mackenzie thought, the two flowers clearly visible in the inset photograph in Fig. 18 are probably fragments nos 16–17 in Fig. 17 a –b, best identified as papyrus–reed hybrids.

Fig. 17. (a) Drawing by Pepi Stefanaki reproducing the current state of the fragments from the north part of the west wall. Differences in the rendering of the various fragments reflect different levels of preservation. (b) 1. Attempt to arrange the fragments in association with the left-facing griffin on the north part of the west wall; pieces nos 8, 9, and 15 appear to be associated with this representation, but their position in the reconstruction is conjectural. 2–3. Fragments which do not appear to belong to the north part of the west wall. Courtesy of Yannis Galanakis and Pepi Stefanaki.

Fig. 18. Modern colourisation of PhEvans Book 8, 32, no. E.Top. 676a (= Brown Reference Brown2000, fig. 19). It shows the north and west walls of the Throne Room in April 1900. Large painted fragments are clearly visible, including the reed-looking plants crowned with a papyrus–lotus arrangement (inset for detail), which today are only partially preserved. Colours on this photo are approximate only. Produced by Dynamichrome. Original photograph courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 19. Part of the griffin's chest and plants, from the north part of the west wall of the Throne Room (Fig. 17a:21), with 10 cm scale. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

Fig. 20. (a) Drawing by Pepi Stefanaki of the crest in ochre background (Fig. 17a:22), now stored with the fragments from the north part of the west wall. Courtesy of Yannis Galanakis and Pepi Stefanaki; (b) Drawing by Mark Cameron of the same fragment (CAM 235). Courtesy of the British School at Athens.

Fig. 21. Reconstruction line drawing of the west wall of the Throne Room based on archival and archaeological data. For this reconstruction, we have assumed that the ‘stone veining’ in the south part of the west wall continued to the floor. Nothing is recorded as coming from the lowermost part of this wall either archaeologically or in the extant archival material (but see also Figs 22–23 for alternative suggestions). Prepared by and courtesy of Ute Günkel-Maschek.

Fig. 22. Colour reconstruction of the Throne Room by Theodore Fyfe, 1901 (KnDrA II.B/4). This drawing formed the basis for Lambert's 1917 drawing (Fig. 23 here). W: 55 cm × H: 41 cm. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 23. Edwin Lambert's 1917 colour reconstruction of the Throne Room (KnDrA II.A/7 = Evans Reference Evans1935, vol. 2, frontispiece). W: 56 cm × H: 38 cm. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

-

5 – west wall, south part: the panel with the best-preserved, crested, wingless crouching griffin in right profile, from the south side of the entrance to the ‘inner sanctuary’ set among floral decoration and four undulating red and white bands. This panel, smaller than when first discovered (Figs 24, 25), is today on display in the permanent exhibition of the Archaeological Museum at Herakleion (‘Minoan painting’ gallery). Dimensions of panel: W: 260 cm × H: 193 cm. Archival and excavation references: AE/NB 1900, 16 and 18 April, 46–9; DM/NB 1900.1, 17 April, 42; KnDrA II.B/2a–d and B/2i, including a pencil sketch by Fyfe (1900); Evans Reference Evans1935, 911, fig. 884 and pl. XXXII between pp. 910 and 911 (not identical but very similar to the one on display); also Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 3, 109–10, pl. 127.

Two registers of white and red bands from the uppermost part of the wall are partially preserved in this panel. The tail of the griffin and the lowermost part of the crest are also partially preserved. The crest was possibly raised, not least as the fragment immediately to the left in the present restoration (where the crest would have continued) does not belong there but in another area of the composition (i.e. leaving space for a raised crest to appear as shown in the original excavation drawings).Footnote 14 The front part of the neck and front paw are not preserved. A red line, painted freehand (again, not very straight) and with no traces of incisions or rope marks, separates the upper part of this fresco from the lower part where the ‘veined stone’ dado decoration appears.

In contrast to the image now adorning the Throne Room at Knossos, this griffin – from which all other Throne Room griffins are modelled – does not have outer pendent curl-tip ‘plumes’ on the neck (contra Evans Reference Evans1935, 910, who is clearly describing Gilliéron's drawing [pl. XXXII] rather than the actual fresco fragments, e.g. compare Figs 24, 25, 26).Footnote 15 Additionally, the ghosts of two thin papyrus flowers are today barely visible on top of the plant in front of the griffin, and another similar group may have existed further to the right, judging by Fyfe's drawing (Fig. 24). These flowers were probably combined with a lotus, similar to the arrangement known from the north part of the west wall, the north-east corner and the south end of the west wall. The Gilliérons in both the 1913 and 1930 restorations used only single papyrus flowers for crowning some of the plants in the Throne Room. More noticeable differences between the Gilliérons’ work and the original fragments include the thickness of the neck of the beast – thinner rather than thicker as shown on the reconstruction – and the number of flowers in front of the beast – three instead of two that appear in the Throne Room restoration. As suggested by the archival drawing (Fig. 24), this fresco preserved more fragments at the time of excavation than it does today. At the left side and at the back of the griffin, some kind of fern plant (most likely a hybridised papyrus–lotus flower) was preserved, in a similar position to the plants on the north part of the west wall, and also on the north-east wall mentioned above (Figs 7, 17 b).

On the opposite side, on the east wall of the corridor, more plaster fragments were preserved in situ. Nothing is mentioned about these fragments in the archives or the published reports. We assume that they might have been painted plain red with bands at the top, similar to the lustral basin (a fragment still clinging on the wall visible in PhEvans Book 8, 29, no. E.Top. 663A = Evans Reference Evans1935, suppl. pl. LXIII).

Fig. 24. The best-preserved of the Throne Room griffins from the south part of the west wall in a watercolour drawing, probably by Theodore Fyfe, c.1900. KnDrA II.B/2a. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fig. 25. The best-preserved of the Throne Room griffins as displayed at Herakleion. Courtesy of ΥΠ.ΠΟ.Α. Τ.Α.Π. – Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund.

Fig. 26. Watercolour drawing of the best-preserved griffin from the south part of the west wall of the Throne Room at Knossos, possibly by Gilliéron, the younger. KnDrA II.B2/i = Evans Reference Evans1935, col. pl. XXXII. W: 87 cm × H: 70 cm. Courtesy of the Arthur Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

-

6 – Lustral basin (Figs 8, 22): various large fragments from the area of the basin. These fragments are still preserved in situ, mainly on the west and south parts and to a lesser extent on the east wall of the basin. Archival reference: KnDrA I.WW/8. No mention of the lustral basin's decoration is made in the excavation notebooks.

The walls were painted red, bearing at the top two registers of white/grey and red bands (also Evans Reference Evans1935, 908–9, fig. 883). These fragments are visible in numerous archival photographs in the Arthur Evans Archive and on Fyfe's 1900 section drawing.

A Note on the Paint Layers and Techniques

As part of the conservation process, the application of macroscopic analysis and Raman spectroscopy provided us with more detailed insights regarding the painting techniques used in the creation of the Throne Room fresco. Our study confirmed Evans's view that all paintings were ‘painted on a very thin coating of stucco laid direct on the mud and rubble surface’ of the wall (AE/NB 1900, 18 April, 49). It is worth noting that our attempt to describe the paint layers and techniques used in the Throne Room decoration is hindered by considerable paint loss in various areas of the wall paintings and also by their original restoration by the Gilliérons. Furthermore, it was not possible examine the layers of the lime plaster in a non-destructive way because all the fragments from the Throne Room have been boxed in a new substrate with plaster of Paris since 1900–1. Despite these shortcomings, a number of observations can be made regarding the paint layers of the ‘palm fresco’ and the techniques used in its making.

The creation of the paint layers began with the preparation of the wall surfaces around the benches and throne. The surface of the masonry was covered initially with a layer of mud plaster containing impurities and plant fibres. The next step involved the application of a coarser plaster, which was followed by a fine-powder plaster: it was on this final plaster that the coloured composition was created. In all these layers, lime (calcium hydroxide) was used as the binding material. Around the throne, the plaster followed carefully the contours of the stone seat (Figs 1, 4, 16), incorporating it seamlessly in the composition (i.e. throne and fresco forming an indivisible whole).

After completing the application of the lime plaster, the artists initially defined the area of the composition within which they would paint. On the still-wet final layer, they created with a thin string the horizontal lines of the bands on the upper part of the walls. In the section between the throne and the bench, the artists did not use a string but a sharp tool to engrave a (freehand) guideline. In the next step, this line was covered by red pigment. This red line therefore helped divide the composition into an upper and lower section, the former including the griffins and plants and the latter the imitation of ‘veined stone’ and, in the case of the throne, the ‘altar’. Having defined these two sections, the artists created a draft design of the composition on the wet plaster. In areas where paint loss can be observed, this draft design is still visible with the naked eye: for example, on the ‘altar’ by the throne and beneath the white impasto a red-orange colour which was originally applied as a guideline can still be seen.

The application of pigments was done in layers. The red undulating bands were the first to be painted on the upper section (the red identified as hematite Fe2O3, Fig. 15:14). The white undulating bands are simply the final lime plaster, and thus the calcite CaCO3 that remains visible (Fig. 15:15). At this stage, the red pigment was also added to the ‘altar’ and the grey pigment in the altar's two ‘semicircles’ (the areas analysed with Raman [Fig. 15:11–12] yielded carbon black for the pigment used there). Although conjectural, it was possibly at this same time that the ‘veined stone’ was painted, as wet plaster was required for its creation. Employing a freehand technique, the artists created the colourful veins, having at their disposal only three colours (red, ochre, black). With a brush, they applied each pigment onto the fresh white plaster using different proportions of binder and pigment to change the volume and tone of each stroke.

Special care was taken in making the palm tree. The artist(s) made an effort to distinguish the palm's red trunk and red leaves from the red background of the undulating bands: they applied yellow ochre to the lower part of the tree, making it even more distinguishable, while for the red leaves they achieved a different tone from the one that appears in the undulating red background. They therefore display a good, practical, grasp that a powder of different particle-size distribution results in marked differences in tonality. They probably used ochre in combination with red in an attempt to render the leaves in a different tone of red from the dark red of the undulating background. To make sure that the palm's trunk and its leaves would stand out clearly from their background, the artist(s) outlined them with impasto white dots, creating a distinct dotted line. Impasto white dots were also used on the dates, three dots for every fruit. Despite the bad preservation of the leaves, we are of the opinion that the red of the palm was added either completely on top of the red undulating background or at least partially (e.g. a red outline was first painted for the leaves, only for them to be filled shortly after with a different tonal red pigment from the undulating background). A white impasto line was also painted on the upper part of the lowermost undulating band.

Raman spectroscopy on the ‘palm fresco’ was carried out by the Institute of Electronic Structure and Laser of the Foundation for Research and Technology Hellas (IESL-FORTH) at Herakleion. The complete characterisation of pigments with a portable Raman was limited because of the existence of a thick varnish layer from previous restorations. Raman, as a non-destructive technique, can detect only the surface of a material. The varnish resulted in very strong fluorescence emission which on most spots blocked the creation of Raman spectra, preventing the detection of the chemical type of pigments. Although we tried to characterise the difference between these two red pigments (leaves and background), after several trials on different spots we were able to detect only hematite (Fe2O3) by the Raman spectroscopy (see e.g. Fig. 15:5, 7, 9, 14).

On the second painted layer, the griffins were created with white impasto. On the ‘palm fresco’, in particular, the use of impasto is observed on the animal's paw and on the frame of the ‘altar’. All the details of the griffins were created on this white layer (e.g. the red nails, the use of cross-hatching and s-shaped lines on the body of the beasts, the decoration on the chest and the details on the crests). The plants were also painted on top of the bicolour background (i.e. white and red undulating bands). The final brushstrokes on the plants were the black parallel lines (‘veining’) on the grey leaves and the details of the flowers (e.g. the orange or red smaller leaves).

To sum up, four pigments were used for the painting of the Throne Room's decoration: (1) white plaster (calcite CaCO3 lime), attested in the horizontal bands, the body of the griffins, the white background (which formed part of the undulating bands), the ‘altar’ and the crests; (2) carbon black, attested in the area of the ‘altar’, in the plants, in the decoration of the griffin's body, in part of the crest and as an outline for one of the horizontal decorative bands on the upper part of the wall; (3) red (hematite, Fe2O3) – the most dominant colour in the Throne Room – which is attested in the decoration of the griffin's body, the undulating bands, the palm, the crests, the smaller plant leaves and the ‘veined stone’; and (4) ochre/yellow (unidentified pigment), as attested in the ‘veined stone’, some of the small plant leaves, the cross-hatching on the griffins’ bodies and also in the crest set in an ochre background (Fig. 20). The lowermost undulating band, which appears to the naked eyed more grey than white (especially in the ‘palm fresco’ and the best-preserved griffin from the south part of the west wall), was in all likelihood originally white, a point further supported by the small fragment preserved with the griffin from the north part of the west wall (Fig. 19).

A BRIEF HISTORIOGRAPHY OF POST-EXCAVATION RECONSTRUCTIONS

There have been three major phases in the reconstruction of the decorative programme of the Throne Room: the first belongs to Arthur Evans and his artists, the second to Mark Cameron and the most recent to Elizabeth Shank.

Evans's attempt to reconstruct the decorative programme has numerous iterations, on paper and more concretely on the walls of the Throne Room. The process of reconstruction started as early as 1900, as Fyfe's archaeological drawings suggest. Fyfe accurately presents the state of excavation (Fig. 8). In 1901, he produced another drawing – a coloured reconstruction this time (Fig. 22) – which was subsequently used as the basis for Edwin Lambert's famous 1917 drawing (Fig. 23). Unlike Fyfe's drawings, however, Lambert's illustration has several problems in the rendering of the floral elements and the absence of the ‘palm fresco’ to the right of the throne. This absence is actually the most problematic element in Evans's reconstructions.

Should we explain Evans's neglect of the ‘palm fresco’ as a result of his unreliable memory, or was this painting out of sequence, so to speak, in his scheme of the evolutionary development of artistic motifs? There are many reasons why this particular painting might have been overlooked, and there is indeed something intriguing about Evans's ‘partial’ memory. For example, his notes in the second volume of The Palace of Minos preserve a vague reference to the ‘palm fresco’ without Evans putting his finger on it:

It is a fair conclusion that a group of palm-trees on a knoll or slight elevation … answered to some painted plaster design, decorative in form but perhaps essentially of a religious character, that filled a prominent place on the Palace walls. (Evans Reference Evans1928, 494)

Both in his publication and in the restoration of the fresco on the walls of the Throne Room, Evans and his restorers decided to ‘forget’ what was actually found in situ. There are a couple of hints that may provide an answer to this puzzle. The first comes from Evans's excavation notebook just two days after the discovery of the ‘palm fresco’. On Saturday 14 April 1900, he made the following note:

Further excavation of bathroom showed another bench symmetrically balancing that on the other side of the seat of honour and another frescoed wall along W side of room. The fresco proves not in any case to be palms but to represent a kind of reed and a flowering rush. There is the usual Mycenaean arrangement – also Egyptian – of the hills of the landscape coming down from the upper as well as the lower border. (AE/NB 1900, 14 April, 38–9; our italics)

This extract is particularly telling about Evans's interest in the symmetrical balance of the composition,Footnote 16 the lack of palm tree representations on the west wall and the possible ‘Mycenaean’ (as he thought back then) and ‘Egyptian’ influences. It is even more telling when compared to Mackenzie's observations of the west wall and on the same day:

Above the part of the seat which runs N–S large pieces of wall-painting came into view. The dado slanted in such a way as to show at once that the fresco had slipped down from its original position on the wall (and) on to the seat and floor. The fallen fresco showed a design of palm trees and other plants and flowers in a hilly landscape, the palms appearing greyFootnote 17 on the red ground. (DM/NB 1900.1, 14 April, 28)

It appears that Evans was already following a different line of thinking to Mackenzie in terms of the composition of the Throne Room's decoration and of the significance of the various elements that appeared on it. This discrepancy becomes even more baffling when a few days later and in his preliminary report he does mention ‘a kind of fern palm’ and ‘tree ferns or palms’ on the south part of the west wall and in association with the best-preserved griffin (e.g. AE/NB 1900, 16 and 18 April, 46–7). In his preliminary report (Evans Reference Evans1899–1900, 40), he mentions rushes and sedge-like plants with red flowers, and that ‘at one point rises a palm tree and on the landscape continuation on the western wall a fern palm was carefully delineated’.

Another hint, for Evans's ‘absent-mindedness’ – if it can be described as such – and the progressive ‘disappearance’ of the palm tree from discussion on the Throne Room, may be included in the following description of the Throne Room fresco in the last volume of The Palace of Minos:

A pair of good examples of these [altar-bases] in relief combine to support the baetylic column, and the fore-feet of the two lions of the Mycenae gateway. A striking religious parallel indeed is here presented by the altar-base as thus depicted beside the throne and the semi-divine personage that once occupied it … This aspect of the throne as forming the centre of a religious composition is well brought out in the photographic view (fig. 895) … with the painted stucco designs on its walls as restored, showing on either side of it the altar-bases and confronted Griffins. (Evans Reference Evans1935, 919–20)

We would argue that Evans's main focus of attention in the Throne Room composition was on its religious nature (the ‘altar-base’) and on the antithetic scheme (his ‘Lions’ Gate scheme’) – a scheme that he had in mind as early as 1901, if not earlier (Harlan Reference Harlan2011), as shown by the discussion of some lentoid seals with antithetical representations and of the Lion Gate at Mycenae as part of his work on the ‘Mycenaean tree and pillar cult’ that formed the basis of his concept of Minoan religion (Evans Reference Evans1901, 156–69). Having the picture of ‘griffin supporters’ of a central divinity in mind, the palm in the Throne Room literally stood in the way between the griffins and the throne. So, in contrast to the griffin and the ‘altar-base’, which both belonged to the cycle of heraldic compositions framing a divinity or sacred object in the ‘Lions’ Gate scheme’, Evans omitted the palm in the ‘reconstitution’ of the Throne Room – his attempt to create an image as impressive as the Lion Gate at Mycenae, with the occupant and throne taking the place of the divinity (Evans Reference Evans1901, 151).

This idea of recreating, and immersing himself in a ‘living world’, is why, we suspect, Evans does not seem to have been at all worried by some of the Gilliérons’ more imaginative reconstructions, or to have noticed the obvious contradictions or anomalies in the vegetation on the Throne Room fresco. To Evans, the Gilliérons’ reconstructions could not be ‘wrong’ in any meaningful sense, since they were merely what his informed imagination led him to believe must have, or ought to have, been there. They filled in the gaps, and made his increasingly idealised civilisation more complete and more real (Sherratt and Galanakis, Reference Sherratt, Galanakis, Simandiraki-Grimshaw and Sattlerforthcoming). As a result, the restorations by the Gilliérons in 1913 and 1930 ignored the ‘palm fresco’ and established a balanced composition in the Throne Room – one that has become emblematic ever since.

Mark Cameron's detailed study of the fragments from the Throne Room offered the next major attempt to reconstruct its decorative programme. Cameron was the first to reintroduce the ‘palm fresco’ into the room's iconography (Cameron Reference Cameron1976; Reference Cameron, Hägg and Marinatos1987; and his unpublished notes in the BSA archives). The placement of the crest in ochre background – one of the fragments from the panel associated with the north side of the west wall, as mentioned above – with the griffin to the right of the throne, made Cameron change the colour scheme of the undulating bands and add palm trees in either end of the north wall in an attempt to explain the colour transition of the bands. Our analysis, however, apart from clarifying details on the ‘palm fresco’, also suggests that the colour scheme of the undulating bands was, in all likelihood, consistent on all three walls where iconography appears. This scheme is probably the most secure element in the restorations of Fyfe, Lambert and the Gilliérons, and the crest in ochre should therefore be dissociated from the north wall's decorative programme (for the various restorations of the Throne Room paintings see Evely Reference Evely1999, 56–9, 65 and 202–3).

The most recent attempt to establish in detail the Throne Room's iconography stems from the work of Elizabeth Shank and her careful study of the fragments from the north side of the west wall (Shank Reference Shank2003; Reference Shank, Nelson, Williams and Betancourt2007; Shank and Balas Reference Shank, Balas, Foster and Laffineur2003). Following Cameron's steps, Shank identified a second ‘crest’ among these fragments: this second ‘crest’ was set on a red background, not ochre as is the case with Cameron's fragment. Following her discovery, Shank put forward two interpretations: that this fragment showed either a raised crest or a wingtip (on the latter see Shank Reference Shank2003, 132–7; Shank Reference Shank, Nelson, Williams and Betancourt2007, 162–4, fig. 19:5; also Blakolmer Reference Blakolmer, Blakolmer, Weilhartner, Reinholdt and Nightingale2011).Footnote 18

The winglessness of these beasts was actually noted as ‘an unique peculiarity’ as early as 1900 (Evans Reference Evans1899–1900, 40), and it remains so: in a corpus of more than 330 examples (Zouzoula Reference Zouzoula2007), wingless griffins in Aegean art are extremely rare.Footnote 19 Yet enough remains from the best-preserved griffin on the south part of the west wall (Fig. 24) to ascertain its winglessness. The striking similarity in the rendering of the body between this griffin and the one on the north part of the west wall suggest to us that both beasts were wingless. Although it is speculative whether the beast(s) on the north wall was/were also wingless, we note the complete lack of any other fragment indicating the presence of a wing from the corpus of extant fresco fragments from the Throne Room at Knossos. Moreover, the two ‘crests’ match perfectly – in decoration, overall arrangement and artistic details – with the lowermost part of the crest from the best-preserved griffin on the south part of the west wall. Griffin wings are most often rendered differently from crests (e.g. Cameron Reference Cameron1976, vol. 2, pl. 131A–K, vol. 3, 113–14). The Throne Room ‘crest’ fragments also find iconographic parallels in a number of examples showing raised crests, including the Ayia Triada sarcophagus (Long Reference Long1974, pl. 11, fig. 26) and the Menidi and Kazarma seals (CMS I, no. 389 and CMS V, no. 583).

The two ‘crests’ that are preserved on the west wall (north and south parts) appear to be equidistant from the lowermost band that decorates the upper part of that wall. The presence of the band and of hybrid papyri or flowers near the two ‘crests’ confirms their orientation and approximate height in the wall composition even if one of them (the one set on an ochre background) may not actually come from the north part of the west wall. Their placement in the composition could therefore potentially correspond to the area where one might have expected a crest to end, not least as in the best-preserved griffin (south part, west wall) only the lowermost part of the crest is actually original.

To sum up: what everyone has imagined on the walls of the Throne Room as a result of successive reconstructions was not what was there originally or even what was discovered in 1900. Evans and his team found larger painted fragments with parts now missing: from the ‘palm fresco’, the ‘veined stone’ dado from the left of the throne, and also part of the painted decoration discovered on the north and south parts of the west wall. Set within an undulating ground of alternating red and plain off-white bands, the decoration of the Throne Room showed crouching griffins on the east part of the north wall and on the north and south parts of the west wall (Figs 21, 27). The beasts on the west wall were wingless and most likely had upright crests. They were surrounded by a thicket of reed-looking plants (also referred to here as ‘papyrus–reed hybrids’),Footnote 20 with light blue-grey stems and occasionally a dark-grey outline and veining (Fig. 19). Some of the plants have yellow or red leaflets and red budsFootnote 21 and appear to be flowerless, while others are crowned with a papyrus–lotus arrangement, similar to the one that appears on the body of the griffins (Figs 7, 17 b, 18, 21).

Fig. 27. Photomontage of the north wall of the Throne Room. Prepared by and courtesy of Ute Günkel-Maschek.

A palm was placed on at least one side of the throne on the north wall, to the right of the viewer. The crown of the fruit-bearing palm appears to grow out of the trunk, starting with a lower group of three thick and arched branches, followed above by a cluster of fruits (Fig. 11). The cluster is topped by another group of three thick – but less arched – leaves growing on either side. The leaf bud, usually growing from the midst of the tree, is not preserved but can be reconstructed based on Fyfe's section drawing. The particular rendering of the leaves and fruits will offer a good starting point to assess the artistic tradition to which the palm in the Throne Room fresco adhered (more below).

A ‘veined stone’ dado adorned the lower section of the south part of the west wall and also the north wall and the north-east corner. The direction of the ‘veins’ is not consistent in all walls and is different from that shown on all available reconstructions. Yet this ‘veined stone’ dado pattern probably adorned all the walls in the Throne Room which bore figural decoration on the upper section. An incurved ‘altar-base’ was painted on the right side of the throne (Fig. 11). The conservation work on the relevant fragment of wall painting has led to the unquestionable identification of the depicted object as an ‘altar-base’, and refutes a possible ambiguity intended by Cretan artists in rendering a shape similar to both altar-bases and friezes of ‘half rosettes’ (Reusch Reference Reusch and Grumach1958, 349–51; Niemeier Reference Niemeier1986, 84–5; also Evans Reference Evans1928, 607–8). However, the existence of a similar ‘altar-base’ on the left side of the throne is speculative, as no remains were found there during the 1900 excavation.

Our conservation and analysis of the available painted fragments, in close juxtaposition to the extant archival information, has helped clarify a number of details which appear to have been misunderstood by the Gilliérons in their reconstructions (on paper and at Knossos): for example, the decoration on the body of the griffin, the thickness of the neck of the beast, and the flora in the Throne Room. Furthermore, a number of the fragments now stored together as coming from the north part of the west wall do not appear to belong to this wall (nos 10–14 and 22–3), as already noted by Cameron (Reference Cameron1976) and corroborated further by Shank's study (2003). In the following section, we try to establish the place of the Throne Room decoration in the history of Cretan imagery.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND STYLISTIC ANALYSIS

The archaeological investigation in the Throne Room area carried out by Vasso Fotou and Doniert Evely under the direction of Sinclair Hood in 1987 concentrated on rooms 44–8 to the north and west of the Throne Room (as reported in Catling Reference Catling1987–8, 68; Fotou and Evely Reference Fotou and Evelyforthcoming).Footnote 22 This investigation touched upon the north and west walls of the Throne Room, examined from the side of rooms 47, 48, 44 and 44a (Fig. 2). The soundings made there suggest with confidence that the north and west walls of the Throne Room were built from bottom up at the beginning of what the excavators call ‘Period III’, which they date at present to LM II. The decoration of the Throne Room, as it can be reconstructed from the extant fragments, could therefore have been either contemporary with the remodelling documented in the area – and if that was indeed the case, it lasted up to the final destruction of the palace – or done in the course of Period III of Fotou and Evely, replacing another revetment which did not leave any trace. Stylistically, we consider a LM II date for the execution of the Throne Room's decoration highly possible.Footnote 23

It is worth noting that the lime plaster that covered the walls and floors of rooms 44–8 had been repeatedly renewed (the new layers were laid over the old ones).Footnote 24 The 1987 investigation also showed, contra Mirié (Reference Mirié1979) and all published plans since, that there was never a door between rooms 44 and 45 (Fotou and Evely Reference Fotou and Evelyforthcoming; mention is also made in Goodison Reference Goodison, Laffineur and Niemeier2001, 182). Rooms 44 and 44a formed part of a unit in LM II with the Throne Room, the lustral basin (rooms 42–3) and the anteroom (room 41), with no direct connection to the Service Section (Fig. 3). What is less clear is whether the door at the end of the corridor to the west of the lustral basin, where the best-preserved griffin was discovered, gave access to room 38 (‘MM III Room with Repositories’) and room 39 (‘Magazine or Gallery of the Jewel Fresco’) or – most likely – was blocked in LM II. The important findings of the 1987 investigation – as these have been made available to date by the excavators – will be taken into consideration as we discuss the decorative programme of the Throne Room within the broader context of Minoan and Aegean art.

Of Palm Tree(s) and Wingless Griffins

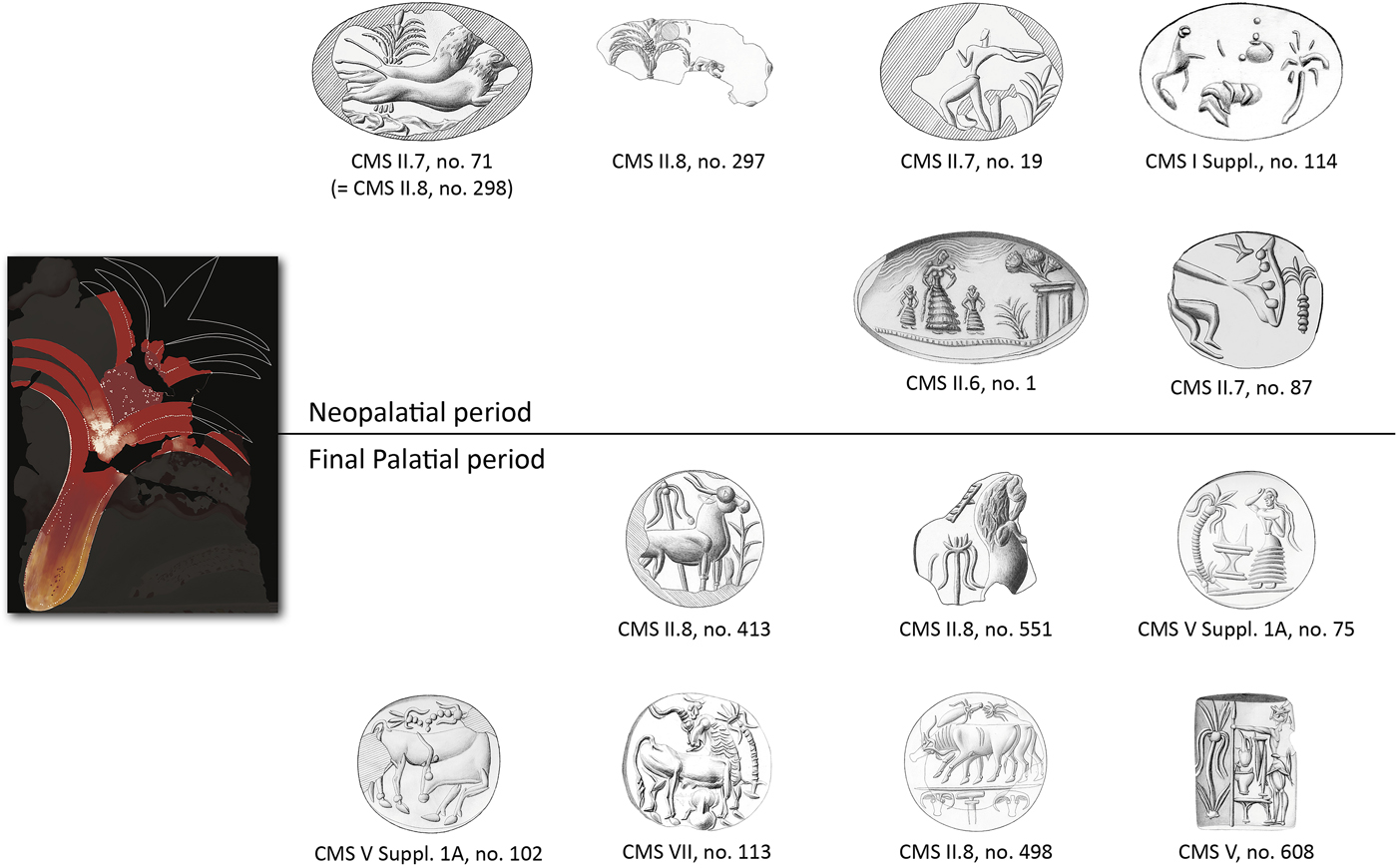

The renderings of the fruits and crown of the tree depicted next to the throne provide the most significant elements to assess the ‘palm fresco's’ place in Cretan art. Generally, the history of palm trees goes back to the Protopalatial period, when the plant made its first appearance in pottery decoration (e.g. a palm on a MM IIB cup and a jug from Phaistos, see Pernier Reference Pernier1935, pls 20a and 31; also Pelegatti Reference Pelegatti1961–2). From early on, the upright position of the fruit cluster markedly contrasts with the heavy, drooping fruit clusters of the common, cultivated, date-palm (Phoenix dactylifera), supporting an identification, as also in the case of the Throne Room example, with the Cretan date-palm (Phoenix theophrasti). The antiquity of rendering the fruits in this position is implied by a polychrome jar from the Loomweight Basement, for which Evans already noted a ‘local touch’ in the rendering of its infructescence (Evans Reference Evans1928, 493; also Dawkins Reference Dawkins1945).Footnote 25 Seal images from Knossos and Kato Zakros (CMS II.7, no. 71 = CMS II.8, no. 298, and CMS II.8, no. 297) (Fig. 28) and the left of the tall palms in the West House miniature frieze from Akrotiri on Thera provide a very similar rendering (Doumas Reference Doumas1999, 64–5, figs 30 and 31): in these Neopalatial images, the crowns consist of thick and arched leaves in an even arrangement, with a leaf bud growing out from the top and the cluster of fruits placed in the midst of the crown.

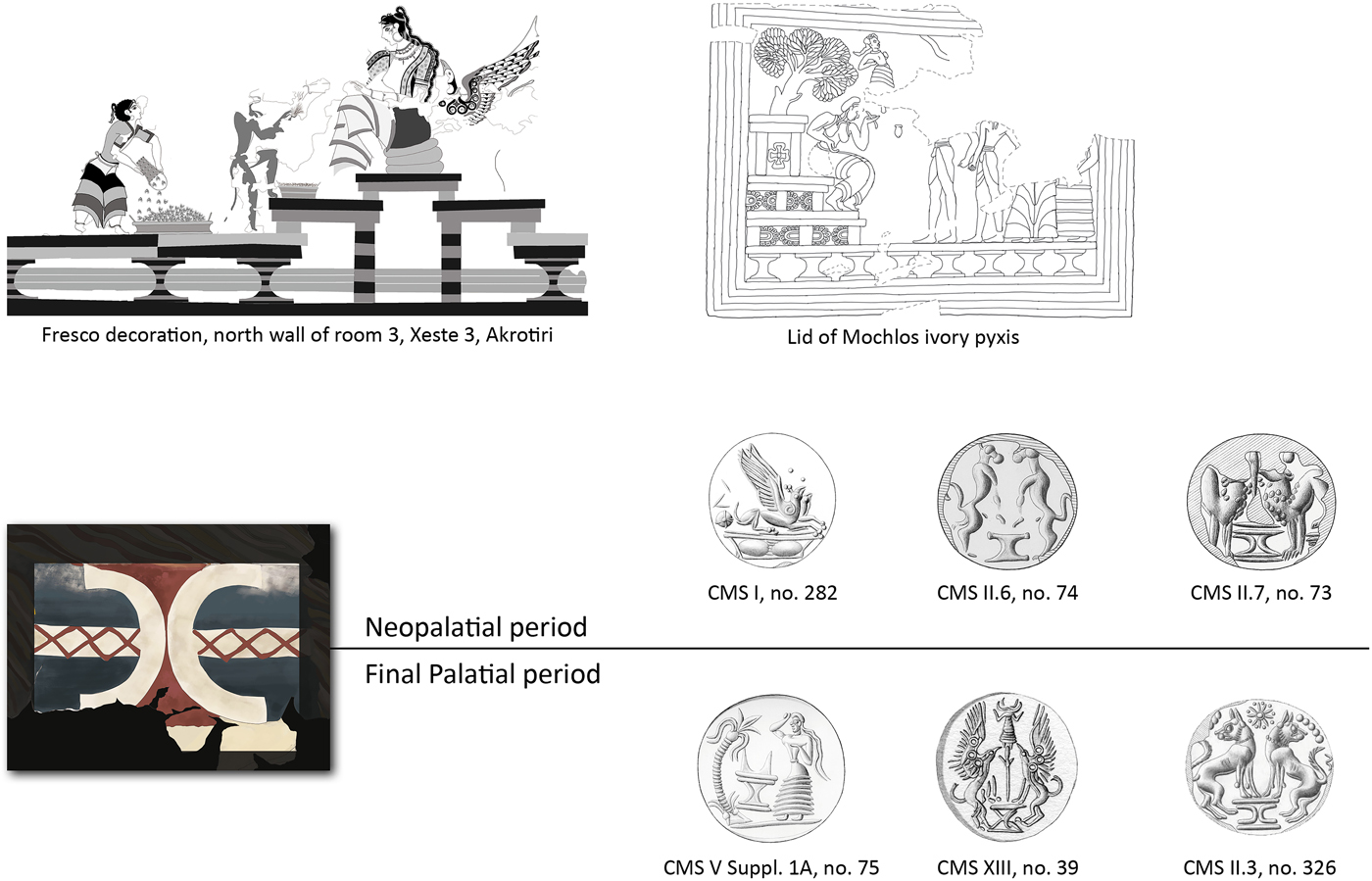

Fig. 28. A selection of images from seals and sealings with palm trees from the Neopalatial and Final Palatial periods. All images of seals and sealings reproduced by courtesy of the Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen Siegel (CMS), University of Heidelberg. Prepared by and courtesy of Ute Günkel-Maschek.

The particular rendering with the infructescence or clusters of fruits separating upper (younger) and lower (older) leaves from each other, and with new leaves unfolding at the top of the crown, finds its earliest attestation in the Kamares-style pottery decoration (Walberg Reference Walberg1976, 193, fig. 48:25.i.7).Footnote 26 Closest in shape to the arrangement of palm leaves and fruits in the Throne Room are the palm crowns above red trunks in the LC I (LM IA) wall painting from the ‘Porter's Lodge’ in Akrotiri, which show two groups of blue palm branches separated from each other at the height of an upward-growing cluster of yellow and red dates (Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos, Betancourt, Nelson and Williams2007, 136 and pls 15:2 and 15:5). Similar (though apparently no clusters of fruits are preserved) are the date-palms in the Minoan or ‘Minoanising’ taureador scenes from palace F at Tell el-Dab‘a, now dated by the excavators to around 1500–1450 bc (Bietak, Marinatos and Palyvou Reference Bietak, Marinatos and Palyvou2007, 89, figs F171, F172, F187, F188; Rüden Reference von Rüden2011, pl. 42d).

The general shape of the tree itself, with its rather short, straight stem – as opposed to the long, slightly bent stems of the palms in the fresco from the ‘Porter's Lodge’ and elsewhere – finds parallels in Neopalatial glyptic scenes, such as the palm tree(s) next to ‘tree-shrines’ on CMS II.6, no. 1 from Ayia Triada, on CMS VI, no. 362 in Oxford and on the largest gold ring from the tomb of the LH II ‘Griffin Warrior’ at Pylos (Davis and Stocker Reference Davis and Stocker2016, 640–3 with fig. 10). Similar in shape are also the small palms in the LC I miniature frieze from the West House, Akrotiri (Doumas Reference Doumas1999, 64–5, fig. 30). However, the detailed rendering of their stems differs remarkably from the plain stem of the palm in the Throne Room fresco, with its auburn contour line bearing only remote resemblance to the protruding remains of dead branches shaping the outer contour of the Neopalatial palm trees.

After the Neopalatial period, the palm continued to be depicted in Minoan art. Two LM II palace-style jars from Knossos show rows of palms with arched leaves and a leaf bud, though without fruits, separated by rosettes in circles (Niemeier Reference Niemeier1985, 76–7, fig. 24, 7, pl. 13, cat. nos III B 1 and III B 2). Yet the majority of post-Neopalatial palm representations are rendered in a remarkably different way from that attested in the Throne Room ‘palm fresco’ (Fig. 28). This different rendering made its first appearance in LM IB / LH IIA, namely the simplified and stylised ‘drooping and upright leaves’ variant as opposed to the ‘naturalistic’ variant of the Neopalatial period to which the Throne Room ‘palm fresco’ finds its closest parallels.

A good example of this ‘new’ rendering is the fruit-bearing palm on the ‘Violent Cup’ from Vapheio, dating to LH IIA (Davis Reference Davis1974, 475, figs 5, 7; 477, fig. 12, 479, fig. 17).Footnote 27 It shows the lowermost leaves drooping close to the trunk, while the cluster of fruits is placed in the middle of the crown. Above are two curved leaves with a third, straight, leaf bud growing upwards from the middle of the palm's crown. Two young palms growing from the ground are also shown in this composition. They are rendered in a similar fashion: two arched leaves on either side and one straight in the middle above.Footnote 28 After the end of the Neopalatial period, the crown shape of the mature palm with long drooping leaves (tips pointing outwards) and either short upward-growing leaves or a larger, single leaf bud (as in LM III examples), became the standard rendering of date-palm representations in Minoan art: from seal images (CMS II.8, no. 498 from Knossos; CMS II.8, no. 551 from Knossos; CMS V Suppl. 1A, no. 75 from Knossos; CMS V Suppl. 1A, no. 102 from Chania; CMS V Suppl. 1B, 137 from Antheia in Messenia) to painted larnakes (Watrous Reference Watrous1991 with pls 83b, 83f, 84e, 87a, 92d, 92g, 92h, 92i) and pottery.

To sum up: the palm from the Throne Room stands out in preserving the Neopalatial tradition at a time when artistic production favoured, in various media, the simplified and stylised ‘drooping and upright leaves’ variant for the palm tree (Fig. 28). Given the suggested date for the construction of the north wall in LM II, it could be argued that the ‘palm tree’ in the Throne Room at Knossos forms one of the last attestations of the ‘naturalistic’ variant in the history of Cretan art.

Yet there is also a certain innovative spirit permeating the creation of the LM II decoration of the Throne Room: on the palm tree, this attempt can be detected in the auburn and red colour of the trunk and of the leaves (Fig. 13). This colour scheme breaks with the established Minoan convention of rendering leaves of palms either in blue colour only, or with blue and yellow, with the bicoloured rendering possibly reflecting the iridescence of the leaves in the sun. For example, this colour convention can be traced in the West House and in the ‘Porter's Lodge’ in Akrotiri on Thera, at Pylos, as well as in the East Mediterranean (Lang Reference Lang1969, 129, pls 73 and H, no. 11 N nws [Pylos]; Doumas Reference Doumas1999, 64–7, figs 30–4, 187, fig. 148 [Akrotiri]; Bietak, Marinatos and Palyvou Reference Bietak, Marinatos and Palyvou2007, 56–61, figs 59A–B, 60 and 150, fig. 138 [Tell el-Dab‘a]; Rüden Reference von Rüden2011, 74–6, pls 54, 66, 69 [Qatna]). Thus within the Minoan and ‘Minoanising’ painting traditions of the East Mediterranean, the tree depicted next to the throne at Knossos stands out for its bright-red colour. A similar emphasis on red is also observed in the papyrus flowers in the Throne Room, which are painted red instead of the usual blue as, for example, in the House of the Frescoes at Knossos (Evely Reference Evely1999, 116) and the miniature frieze in the West House at Akrotiri (Doumas Reference Doumas1999, 66).

With regards to innovative elements, the wingless griffins must have formed one of the most impactful features to the eyes of the Late Minoan beholder of the Throne Room composition. Although only the foreleg of one such beast is preserved to the east of the throne in the ‘palm fresco’, we have argued above that the creature depicted there was most likely a griffin, similar to the griffins shown on the west wall, on either side of the door leading to the ‘inner sanctuary’ (Fig. 21). Upon a closer look at the design of the creatures on the west wall of the Throne Room, their innovative nature immediately becomes apparent: neither their winglessness nor their floral decoration has antecedents among the corpus of griffin representations in Minoan and Aegean art.Footnote 29 To this, we may add technical novelties such as the use of cross-hatching in order to create an effect of shading and/or volume (Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr1990, 98 and 161; Evans's attempt for ‘chiaroscuro’: 1935, 913, fig. 886).Footnote 30