In the United States, when an indigent person confronts a problem that raises issues of civil law and could benefit from a lawyer's advice or advocacy, he or she has no guarantee of counsel.Footnote 1 Lawyers' services are not always the best or the only solution to such problems,Footnote 2 but they can be helpful in many situations. Studies of representation and advice typically find that the use of lawyers increases the probability of favorable outcomes (Advice Services Alliance 2003; Reference SandefurSandefur 2006; but see Reference KritzerKritzer 1998). But lawyers are expensive, and their services can be beyond the means of many households. In the United States, the federal Legal Services Corporation (LSC) funds legal assistance lawyers whose work consists entirely of providing representation and advice to indigent people confronting civil legal problems. Nearly 50 million people live in households with incomes low enough to be eligible for LSC services (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2005). For lack of adequate staff and other resources, LSC-funded organizations currently turn away as many clients as they accept (Legal Services Corporation 2005:5–7).

A large, and perhaps increasing, share of the civil legal assistance available to indigent Americans reflects lawyers' work in organized civil pro bono programs. The most recent available information, from 1997, suggests that more than a quarter of the full-time equivalent lawyer staff providing civil legal assistance in the United States reflects this pro bono activity. Reliance on lawyers' pro bono work renders the stock of legal assistance vulnerable to those factors affecting pro bono participation. Empirical analysis of state-to-state differences in lawyers' participation in organized civil pro bono programs reveals that this activity is sensitive to conditions in legal services markets. This finding has implications not only for American social policy, but for that of other nations considering increased use of pro bono as a means of reducing or containing legal aid costs.

American-Style Civil Legal Assistance

Like many other social services in the United States, public civil legal assistance relies on private supplement (Reference MarwellMarwell 2004). Traditionally, civil legal assistance provision in the United States is described as following a “salaried” model, reflecting the organization of government funding and staffing: eligible people receive services from government-salaried lawyers working in special law offices that serve only legal assistance clients (Reference Cappelletti, Garth, Cappelletti and GarthCappelletti & Garth 1978; Reference CappellettiCappelletti et al. 1975; Reference PatersonPaterson 1991:132–4). These federally supported lawyers are only part of the picture, however. Civil legal assistance in the United States has a tripartite structure, comprising law clinics staffed by federally salaried lawyers, clinics staffed by lawyers salaried by funds from other sources, and lawyers working in pro bono programs organized expressly for the purpose of providing civil legal services to the poor. These three sources of assistance are complemented by court-awarded and contingent fee service, which can sometimes be used to fund legal services a client could not otherwise afford (Reference Johnson and ReganJohnson 1999).Footnote 3 When people cannot afford to pay for lawyers' services, whether out-of-pocket or through contingent fees, they become eligible for civil legal assistance.Footnote 4

In both court-awarded and contingent fee service, lawyers take cases in the hope of receiving their fees as part of the court's decision or settlement between the parties. Prevailing parties may receive fees through court award when recovery is authorized by statute, when “the plaintiff's efforts have resulted in an equitable benefit to an identifiable class,” and “where a party has acted in bad faith or disobeyed a court order” (Reference Specter, Grasberger and NewbergSpecter & Grassberger 1980:110; see also Reference KritzerKritzer 2002). The kinds of cases in which courts might award fees include those involving employment discrimination, sex discrimination, consumer credit, consumer fraud, consumer warranties, tenant's rights, government benefits, voting rights, public accommodation, and other civil rights and constitutional issues (Reference NewbergNewberg 1980:7). It is difficult to know how many indigent people receive legal services that are funded through court-awarded fees. Class-action suits can involve thousands of individuals as “clients,” some poor and others not, while test cases can have a wide-reaching impact on many individuals (Reference LawrenceLawrence 1990). In terms of total funding for civil legal assistance, the contribution of court awarded fees is likely small, though only limited data are available to inform this supposition. Legal assistance organizations receiving certain kinds of federal funds are prohibited from pursuing class-action suits (Reference Houseman and PerleHouseman & Perle 2001, Reference Houseman and Perle2003). A survey of law firms and other organizations providing legal services to the indigent in California in the early 1990s found that court awards supplied only 2.8 percent of their total funding (Access to Justice Working Group & Office of Legal Services 1995: Table 7).

Contingent fee service is practicable only for matters involving some kind of money recovery. Under this fee structure, lawyers receive payment in the form of a percentage of any judgment or settlement in favor of their client. If the client loses, the lawyer receives no fee, though the client may still have to pay court costs and other expenses related to the processing of his or her claim. The type of legal matter popularly associated with this service is the tort, such as a physical injury incurred in an automobile accident, consumer product failure, or incident of medical malpractice; however, clients with many kinds of civil legal matters may be served through contingent fee arrangements. The Model Rules of Professional Conduct of the American Bar Association (ABA) prohibit contingent fees for divorce and family support cases (Rule 1.5[d]); all other civil matters are eligible, unless otherwise prohibited in a local jurisdiction.

While a large scope of matters may receive service funded by contingent fees, only some are actually likely to receive it. Because the matter must involve the possibility of some kind of money recovery, contingent fees are impractical for contractual work in which no money changes hands, such as writing a will or renegotiating the terms of a lease, or preventive legal advice, such as explaining to someone when and how to withhold rent from a landlord who refuses to make repairs to a rented property. Using civil litigation or the threat of it to compel a landlord to repair a faulty water heater or a school to reverse the expulsion of a student might be effective, but pursuing such strategies usually would not net contingent fee lawyers any pay. In instances where a money recovery is possible, lawyers have no incentive to take a case on contingent fee if they believe they are likely to lose, or if the amounts at stake are so small that their portion of the award would not cover their costs. A study of contingent fee lawyers in Wisconsin found that such lawyers accepted less than half of the cases presented to them (Reference KritzerKritzer 1997:24; see also Reference Daniels and MartinDaniels & Martin 2002 and Reference MichelsonMichelson 2006). While it is impossible to know what proportion of the poor's use of lawyers' services is funded through contingent fees, available evidence suggests that this quantity is likely substantial.

Surveys of lawyer use suggest that most of the poor's contacts with lawyers involve attorneys in private practice, and that the majority of these contacts involve lawyer fees. According to the most recent national survey, indigent American households experiencing justiciable events consulted lawyers at about three-quarters of the rate of middle-income Americans—for 21 percent, in comparison with 28 percent, of events (Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994a: Table 5–8; Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994b: Table 5–8). Only about one-quarter (24 percent) of the poor's consultations with the attorney “most involved” with their events involved a legal aid clinic of some type (Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994a: Table 5–12); the majority (76 percent) of contacts involved lawyers in private practice (Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994a: Table 5–8). Of these private lawyer contacts, at least one-quarter were suggestive of contingent fees: 19 percent involved a “free initial consultation” that went no further, while 7 percent involved contingent fees in a case that was lost (Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994a: Table 5–12). In an additional 56 percent of contacts with private lawyers, indigent clients had paid or expected to pay at least something for services, with 39 percent paying or expecting to pay the full fee, whether out-of-pocket or out of any judgment or settlement (Consortium on Legal Services and the Public 1994a: Table 5–12).

Civil legal assistance comprises efforts to provide services to low-income people outside the context of fee-for-service and contingent fee relationships (Reference Houseman and PerleHouseman & Perle 2003:1, note 1). The centerpiece of American-style assistance is the federally funded LSC. Federal subsidy had its origins in 1965; the LSC itself descends from one of the initiatives in the War on Poverty overseen by the Office of Economic Opportunity (Reference GarthGarth 1980:17–51; Reference Kilwein and ReganKilwein 1999; Reference Johnson and ReganJohnson 1999). The LSC does not provide services directly, but instead makes grants to legal services programs. Originally conceived as local law clinics (Reference GarthGarth 1980), LSC-sponsored offices today may serve a geographic area as small as a neighborhood or as large as a state.Footnote 5 In 1997, when the United States boasted on the order of one lawyer for every 300 people in the country, the LSC funded the salaries of 3,494 full-time equivalent lawyers, or one for every roughly 14,000 people eligible for their services (Reference CarsonCarson 1999:Table 1; Legal Services Corporation 1999a; U.S. Bureau of the Census 2005).

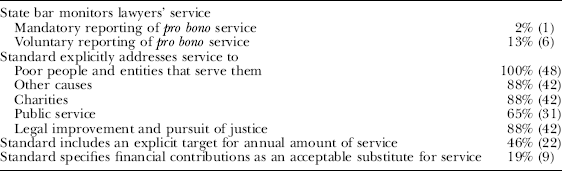

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Professional Standards for Lawyers' Pro Bono Service, United States, 1997: Percentages and N's (in parentheses)

Notes: N=48 states with a code or standard regarding pro bono in 1997. Sources: Center for Pro Bono (1998); Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service (2005b); Board of Governors of the State Bar of California (2002); Reference MauteMaute (2000: Table 1); State of Massachusetts (2005a, b).

A second source of assistance is available from civil legal aid societies that have no affiliation with the LSC. Across the country, more than 650 such societies, including law school clinics, funded by a variety of private sources and government agencies, employ lawyers to provide legal services to people who cannot otherwise pay for them (Reference KatzKatz 1982; Legal Services Corporation 1998a; National Legal Aid and Defender Association 1995; Reference SouthworthSouthworth 1996). Some of these organizations are general practice poor law offices, providing services for a range of problems presented by their indigent clientele. Others direct their services to specific populations, such as immigrants or the elderly, or they target certain types of legal matters and other activities which statute prohibits organizations receiving federal funds to pursue.Footnote 6 In 1997, an estimated 3,607 lawyers were working in such organizations, providing a full-time equivalent lawyer labor force about the same size as that funded by the LSC.Footnote 7

A third source of assistance is provided by lawyers who volunteer their time in service conventionally known as pro bono. Some of this service is “freelance,” in the sense that it is pursued outside of any organized program. Some lawyers freelancing pro bono services determine to do so as part of what they see as their professional obligations, while others retroactively designate as pro bono those services provided to clients who are billed but fail to pay (Reference HandlerHandler et al. 1978:108; Reference LochnerLochner 1975). A large number of lawyers participate in formally organized pro bono programs that target the civil legal needs of the poor. Since the early 1980s, LSC-funded organizations have been required to use at least 12.5 percent of their LSC funding to encourage pro bono participation (Reference McBurneyMcBurney 2003). In 1998, the work of LSC-salaried attorneys was supplemented by 44,600 other attorneys—about 5 percent of those eligible to practice law in that year—who worked on referral from the LSC as part of the Private Attorney Involvement (PAI) program (Legal Services Corporation 1999b). Available evidence suggests that many more lawyers serve in programs that are not part of the LSC's PAI initiative.

The ABA Center for Pro Bono's survey of state pro bono models reports that 135,572 lawyers, or 18 percent of the lawyers in 40 states, participated in formally organized pro bono programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor in 1997 (Center for Pro Bono 1998). These data constitute the most contemporary and comprehensive state-level information available about lawyers' pro bono activity.Footnote 8 Taking the data from these 40 states as an estimate of the share of the national profession that participated in such programs produces a 95 percent confidence interval of between 15 and 21 percent of the profession.Footnote 9 In terms of the number of legal personnel involved, pro bono service is the largest component of civil legal assistance in the United States. These lawyers constituted an estimated full-time equivalent staff of between 2,405 and 3,368 in 1997 (see this article p. 93–95 for details). Comparing this labor force to those salaried by the LSC and those in other legal assistance organizations in 1997, more than one-quarter of the full-time equivalent lawyer staff providing civil legal assistance reflected lawyers' pro bono activity.Footnote 10 The substantial reliance of American-style civil legal assistance on pro bono implies that those factors influencing it may also affect the availability of legal aid. In particular, both the amount and the type of available civil legal assistance may be affected by conditions in the markets for legal services.

Pro Bono and Professionalism

The nature of lawyers' relationships to the markets for their services is central to understandings of lawyer professionalism and has been a subject of perennial debate (Reference PatersonPaterson 1996). Proponents of the two prominent accounts, the classical and market control theories, propose different understandings of professionalism's behavioral content. Classically, professions are conceptualized as largely self-regulating collectivities possessed of socially and economically valuable expertise and conscious of a fiduciary role vis-à-vis their clients and society (Reference FreidsonFreidson 1994:200; Reference Parsons and SillsParsons 1968, Reference Parsons1969). Integral to their training is the inculcation of a strong identity as a professional with ethical commitments that include a duty of public service (Reference Parsons and SillsParsons 1968). In the case of law, lawyers work not only for their specific clients but are “officers of the court,” with broad obligations to the system of justice and its proper functioning (Reference GaetkeGaetke 1989). This understanding of professionalism is reflected in the rhetoric of the organized bar, which observes that lawyers' monopoly on the provision of legal advice and courtroom representation obligates them to provide service to those who cannot afford to pay their fees (American Bar Association Commission on Professionalism 1986:298–9; Reference MauteMaute 2000; Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998). Bar leaders and other spokespeople for professional values accordingly exhort lawyers to be generous in giving of their time (Center for Professional Responsibility 1989; Reference RhodeRhode 2004, Reference Rhode2005; Special Committee on Evaluation of Ethical Standards 1969; Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service 2005a). This understanding of professionalism does not require that lawyers give at the expense of their own solvency, but it does imply that lawyers will be responsive to ethical obligations as well as their bottom line.

Proponents of the market control approach regard professionals' behavior as principally reflecting occupational self-interest. Lawyers act collectively through professional associations and other means to try to ensure that they can make a good living, both by encouraging demand for their services and by restricting the supply of those services (Reference Abel, Abel and LewisAbel 1988, Reference Abel1989; Reference LarsonLarson 1977; Reference WeedenWeeden 2001). In this understanding, pro bono work is less like charity and more like philanthropy, targeted giving with the dual purpose of helping its recipient and benefiting the donor (Reference Daniels and MartinDaniels & Martin 2005). This understanding of professionalism suggests that conditions in the markets for legal services, including lawyers' relationships with their clients and with other occupations, will be important factors shaping both the amount of pro bono service lawyers provide and the content of their pro bono activity.

Legal aid scholars have long expressed concerns that strong connections to the market can corrupt or disable lawyers' charity as a means of facilitating the poor's use of law (Reference Carlin and HowardCarlin & Howard 1965; Reference CummingsCummings 2004; Reference KatzKatz 1982; Reference MayhewMayhew 1975; Reference SmithR. Smith 1919; Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998). Most often recognized have been positional conflicts of interest, which emerge from a lawyer's service to classes of clients whose interests may be opposed, such as landlords and tenants, unions and employers, or merchants and consumers. Reginald Heber Reference SmithSmith (1919), in his study of private legal aid societies receiving funding from philanthropic groups of local businessmen, was perhaps the first to identify such conflicts in a legal aid context: many of the societies' clients turned out to have disputes with the kinds of businesses providing the societies' funding.

Positional conflicts are likely to have their most pronounced effects on the distribution of pro bono effort across different types of legal work. In particular, lawyers appear hesitant to take on pro bono cases that place their firms in positions of conflict between the interests of classes of existing and potential paying clients and classes of pro bono clients. For example, a lawyer in a firm that does legal work for one major banking company may be presented with a potential pro bono client who is a consumer with a complaint against a different major banking company. The concern is that the lawyer, if he or she took the pro bono case, would not give zealous representation and incisive advice for fear of antagonizing the paying client, the bank. In attempting to avoid the conflict, the lawyer may simply refuse categorically to take that client and all others with similar legal problems. As one partner in a large law firm observed in respect of these situations, “[w]e know what side our bread is buttered on, and we stay there” (Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998:1409). Evidence suggests that contemporary large law firms sometimes try to get around positional conflicts by proscribing firm lawyers' participation in pro bono representation for entire classes of problems, such as matters involving employment or landlord-tenant law (Reference CummingsCummings 2004:116–21; Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998:1414). Informants at some legal assistance organizations have claimed that “positional conflicts dramatically impact the subject matters [the organization is] able to distribute to lawyers for pro bono work” (Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998:1418).

Reliance on charity in a market context may also affect the sheer amount of available assistance, through market conditions' effect on the amount of pro bono performed. Two dynamics, one internal to the organizations in which lawyers work and one characterizing lawyers' relationship with other occupations, illustrate how this can occur. Most simply, lawyers must be able to afford to do pro bono. Work that is billed to a client for less than the cost of performing it must be cross-subsidized by other work if the firm or the lawyer is to survive in business. Reference KritzerKritzer's (2004) study of contingent fee lawyers in Wisconsin, Reference LochnerLochner's (1975) study of no-fee and low-fee service by private practice lawyers in New York, and Reference MichelsonMichelson's (2006) study of case screening by lawyers in Beijing all depict lawyers as engaging in something akin to portfolio management. Lawyers choose which cases to take and which to decline based, at least in part, on the other actualized and potential sources of revenue in their “portfolio” of work, trying to balance risk and potential payoffs (Reference KritzerKritzer 2004:10–9). Individual lawyers and law firms likely make at least implicit and informal, if not explicit and highly rationalized, calculations about how much pro bono work they can afford to do.

More subtly, pro bono participation may reflect strategies of market closure and the dynamics of competition between law and other occupations. As in other professions, lawyers act collectively through professional associations and other means to try to ensure that they can make a good living, both by encouraging demand for their services and by restricting the supply of those services. One important way in which they achieve the latter goal is by protecting legal work from encroaching occupations (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988). Central to this effort is the need to maintain jurisdictional control of work in the “arena of public opinion” (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:59). Change in public opinion about what specific work lawyers must do and what specific work can safely and effectively be done by other occupations can lead to changes in the regulations designating work as legal (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:59–60); lawyers can then lose both de facto and de jure jurisdiction over some body of previously legal tasks and services. Pro bono service can be understood as an important element of boundary maintenance: as Rhode observes, “[c]haritable contributions have been one way … to reduce demand for less expensive service providers” (2005:97).

When lawyers fail to assist indigent clients with their justiciable problems, other occupations—document preparers, estate planners, financial advisors, social workers—can step in to provide services at fee levels (including no fee) that poor people can afford. Historically, competing occupations have sometimes defended their activities by arguing that the high cost of lawyers' services puts civil justice beyond the budget of many ordinary Americans (e.g., Greenwell v. The State Bar of Nevada 1992). In response to these concerns, state legislatures have both entertained the possibility of legalizing currently unauthorized practice and have actually done so by recognizing non-attorney providers of limited services in areas of historically legal practice, such as immigration (e.g., Reference MooreMoore 2004:11–3). These legislative actions infringe upon lawyers' powers of self-regulation by taking away some of their authority to define what they do as the practice of law.

For lawyers, the concern about unauthorized practice for indigent clients is not an immediate loss of revenue, but the fact that other occupations may come, over time, to be seen as able to provide services historically available only from lawyers. Encroachment may spread from services provided to clients relatively peripheral to legal services markets, such as the indigent, to those provided to clients more central to lawyers' revenue stream. When lawyers feel their work jurisdiction is under threat, they may increase their pro bono work as a way of maintaining visibility in general and in areas of law they perceive as vulnerable to encroachment. Some state professions have exhorted lawyers across the profession to do pro bono work in order to further access to justice in the defense of the boundaries of the profession, as well as to protect the public from unregulated nonlawyers (see Nevada Lawyer 2005).

These two contrasting understandings of lawyer professionalism reflect different understandings of lawyers' motivations and consequently emphasize different factors as salient in affecting lawyers' behavior. In the next section, I compare these visions of lawyer professionalism with empirical evidence about variation in lawyers' pro bono participation across states. The choice of this level of analysis reflects both the structure of the available data and the recognition that, for American lawyers, states are the basic unit of professional organization. Lawyers pass the bar exam and other requirements for practice in individual states and are admitted to practice in individual states. State professions promulgate their own professional codes specifying lawyers' public service responsibilities, and the organized bars of individual states decide whether to initiate and how to support concrete efforts to encourage and facilitate pro bono service.

Lawyers' Pro Bono Service

Professional Self-Regulation

In the classical understanding, part of professional self-regulation involves attempts to identify and activate public service obligations. While some market control theorists would dismiss these activities as merely symbolic, the classical understanding implies that such attempts should both exist and at least reflect, if not cause, lawyers' public service activity. Lawyers' pro bono service for civil matters is almost exclusively voluntary.Footnote 11 State legal professions pursue a variety of activities meant to encourage lawyers to engage in pro bono work.

Every state bar, with the exception of Illinois, has now in its disciplinary code, model rules, or bar association resolutions some language enjoining lawyers to volunteer their services to needy causes (Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service 2005a). Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of these policies in 1997, the year for which state-level data about pro bono participation are available.Footnote 12 All states with a code or resolution regarding pro bono service explicitly singled out the poor as recipients. In most cases (88 percent), other causes were also identified as worthy of lawyers' uncompensated service. Forty-two states (88 percent) suggested that free and reduced-fee services provided to any type of charitable organization could fulfill lawyers' pro bono responsibilities, while 31 (65 percent) suggested that any form of public service could fulfill lawyers' responsibilities. In half of the states (54 percent), the codes gave no guidance about the appropriate amount of pro bono. Among those that did specify an amount, the most common suggestion was 50 hours per year.

The state codes relied primarily on exhortation to signal the importance of lawyers' service. Some implied that lawyers need not personally provide pro bono, by stating that money donations to entities serving the poor could substitute for service. About one-fifth of statements (19 percent) informed lawyers that financial contributions were an acceptable alternative. Most state professions did not monitor service: in 1997, six states attempted to do so with voluntary reporting programs, most often requesting lawyers to report their yearly hours of service on their bar association dues statements; Florida required lawyers to report.

The aspirational statements of the codes are complemented by more concrete strategies. At present, in most states the organized bar provides some level of support to an organization that acts statewide to recruit lawyers, provide training in law or procedure, or otherwise facilitate the work of volunteer lawyers and pro bono programs (National Legal Aid and Defender Association 2005). By 1997, with the exception of Arkansas, Indiana, Louisiana, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming, all states and the District of Columbia had a statewide pro bono program in active operation (Center for Pro Bono 1998). Most of these had some affiliation with the organized bar, though not all were projects of the organized bar. With the exception of Ohio, Oklahoma, and Vermont, the state bar association and/or the state bar foundation provided some level of financial, staffing, or in-kind support to the program (Center for Pro Bono 1998).Footnote 13

These state pro bono programs exhibited four main components: initiatives to attract lawyers into pro bono service and reward them for that service (recruitment and recognition); initiatives to coordinate the work of pro bono and other legal assistance programs on a statewide basis (higher-level facilitation); initiatives to support the training and work of lawyers in local and regional programs (ground-level facilitation); and initiatives to link clients with lawyers (provision). Every state with a statewide pro bono program in 1997 had at least one recruitment or recognition initiative in place. Attempts to encourage service ranged from minimalist to elaborate. For example, the Nevada program reported no recruitment activities but offered awards, certificates, and publicity to those who served, while Maine's program included 10 separate activities designed to encourage or reward service.

Attempts to recruit lawyers fell into two broad types. Most strategies reflected an essentially aspirational approach to encouraging pro bono and were what might be termed diffusely targeted: they were directed at a wide audience and typically consisted of mass mailings, live presentations at bar association meetings, or media campaigns of different types. Like the professional codes, these strategies relied primarily on encouragement and exhortation. Of the total number of recruitment initiatives across all states, 69 percent were diffusely targeted, and 90 percent of states had at least one diffusely targeted initiative. A second group of initiatives were specifically targeted: an individual lawyer or organization was singled out for contact. About one-third (31 percent) of the total number of recruitment initiatives were specifically targeted, and two-thirds (67 percent) of states had at least one such initiative. The most common involved recruiting through personal contacts and attempts by the state pro bono program to work with individual law firms to secure their lawyers' service. Other specifically targeted initiatives included phone-a-thons and targeted mailings (Center for Pro Bono 1998).

As measures of professional regulation of lawyers' pro bono, I take two aspects of state professional codes and two aspects of state pro bono program activities. Among lawyer-observers of the legal profession, monitoring of pro bono service is often suggested as a potentially effective, noncoercive means of getting more lawyers to do it (Reference MauteMaute 2000; Reference RhodeRhode 2005:45–6); one might term this the monitoring hypothesis. It reflects the logic of the classical understanding of professionalism, which views lawyers as holding ethical commitments to public service. Being individually called to account for their fulfillment of those commitments is meant to remind lawyers of their professional obligations and motivate them to take action by providing service. The presence of monitoring initiatives may reflect greater commitment to pro bono on the part of a state's lawyers, or such initiatives may actually work, by inducing more lawyers to serve. In either case, the monitoring hypothesis predicts that states with the initiatives should evidence higher levels of pro bono participation than states without them. As a measure of state monitoring practices, I classify states by whether they ask lawyers to report their pro bono service on bar association dues statements or through some other means. Voluntary reporting schemes, the most common, are classed with mandatory reporting schemes—only one state had such a scheme in 1997—in the analyses.

As a measure of the state professions' positions on the importance of lawyers' direct pro bono service in favor of some other means of fulfilling professional responsibilities, I classify states by whether or not the state professional code explicitly designates a financial contribution to an entity serving the poor as an acceptable substitute for direct service. In the classical understanding, the content of professional regulation should reflect and affect lawyers' behavior. The existence of a financial contribution alternative could express a prevailing sentiment in the state profession that direct service is not necessary; it could also, if rank-and-file lawyers attend to the content of professional codes, encourage lawyers to consider choosing to donate money rather than time. That choice may reflect many different motives, including the press of other business, the wish to avoid positional conflicts, concern that the poor's problems fall outside one's own legal competency, a distaste for direct service to poor people, or a rational calculation that financial contributions to charity are tax-deductible (Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998:1409–12). For any of these reasons, if lawyers are attentive to the content of professional codes, one would expect lower rates of participation in states in which this stipulation exists. One might term this the buy-out hypothesis (Reference MauteMaute 2000; Reference SpauldingSpaulding 1998).

Finally, I examine the relationship between pro bono participation and concrete initiatives to increase the number of lawyers who serve. States in which aspirational standards are supplemented by material attempts to encourage service should exhibit higher rates of service, either because these states have a greater commitment to pro bono, as reflected in their recruiting activity, because the professions' concrete attempts to regulate public service behavior are successful, or both. From the ABA Center for Pro Bono report on state models of pro bono (1998), I calculate for each state the number of each of two kinds of recruitment activities: diffusely targeted activities and specifically targeted activities. I distinguish between the two types of initiatives because research on volunteering behavior suggests that being directly and specifically asked to do volunteer work increases the probability that one will do it (Reference FreemanFreeman 1997:S159–65). If either type of concrete strategy is associated with service, one would expect specifically targeted strategies to be more strongly associated.

Market Conditions

In discussing market control theories of professionalism, I above identified three ways in which markets for legal services may affect pro bono service: through positional conflicts, through the need for cross-subsidy, and through competition with other occupations for specific bodies of work. Because positional conflicts pertain to service to particular classes of clients, one would expect such conflicts to influence the substance of problems receiving aid, but not necessarily how much pro bono service a state or local legal profession would provide. Unfortunately, data adequate to explore the impact of positional conflicts at the level of states do not presently exist. In the analyses here, I focus on those ways in which the market context may affect the amount, rather than the type, of pro bono service provided at the state level: the need for cross-subsidy and interoccupational competition.

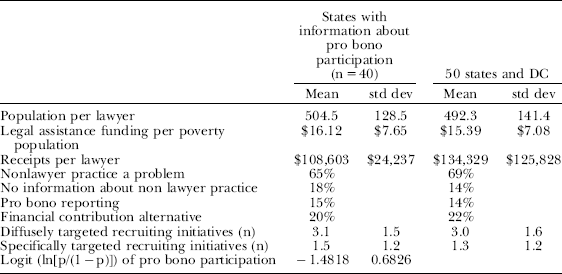

Some lawyers and state professions can more easily afford to provide free services to indigent people because they can subsidize the free services with income from paid work (Reference LochnerLochner 1975; this article p. 85–6). By this logic, states in which the profession takes in more receipts per lawyer should exhibit higher rates of pro bono service than states in which lawyers bring in less money; one might term this the cross-subsidy hypothesis. Cross-subsidy can operate both at the individual level, as individual members of firms or solo practitioners make decisions about how much pro bono work they will do, and at the organizational level, through the presence of “organizational slack” (Reference Cyert and MarchCyert & March 1963). Organizational slack comprises spare resources of funds, technology, skill, and personnel that can be reserved until pressure of work requires them or can be deployed in other activities, such as pro bono service. At the level of states, higher revenues to the legal profession may reflect not only a brisk market for legal services, but also the greater presence of the kinds of legal organizations that perform the most lucrative legal work and accumulate substantial organizational slack, large law firms (Reference Galanter and PalayGalanter & Palay 1991; Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 2005: Chapters 5, 7). As a measure of revenues to state professions, I take the receipts to the state legal services industry in 1997 per lawyer in the state (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2004).

The second way in which conditions in the markets for legal services may affect the amount of pro bono service is through jurisdictional conflicts. If lawyers' pro bono service reflects, in part, an attempt to maintain jurisdictional closure, we would expect states where the legal profession feels that some historically legal work is under threat from other occupations to exhibit higher levels of pro bono service than states in which the profession does not feel under threat; one might term this the interoccupational competition hypothesis. As a measure of whether or not state professions perceive encroachment by other occupations, I take states' responses to the ABA's 1994 Survey on the Unauthorized Practice of Law/Nonlawyer Practice (Standing Committee on Lawyers' Responsibility for Client Protection 1996).

In 1994, three years prior to the pro bono survey, the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility surveyed state entities monitoring the unauthorized practice of law, asking, “Is nonlawyer practice an issue in your jurisdiction?” States answering in the unqualified affirmative are considered to have perceived that law was under threat from other occupations. States not responding to the survey are classified as providing no information. The activities most often cited as experiencing encroachment and the occupations most often accused were precisely those that provide services to personal clients, often those who are less affluent. In descending order of frequency of mention, the most common areas of encroachment were family and domestic relations (especially divorce); wills, estates, and trusts; bankruptcy, real estate; and immigration. One state identified service for low-income persons as a prime area of encroachment. The most commonly identified competing occupation was document preparers, but independent paralegals, real estate agents, accountants, and public adjusters were also reported (Standing Committee on Lawyers' Responsibility for Client Protection 1996:16–22).

Measuring Lawyers' Pro Bono Service

Information about lawyers' participation in organized pro bono programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor comes from the ABA Center for Pro Bono's Pro Bono Delivery and Support: A Directory of Statewide Models (1998). In 1997, the Center queried local and statewide pro bono programs, bar associations, organizations funded by the LSC, and other nonprofit organizations that provide legal services or referrals for legal services (personal communication, Cheryl M. Zalenski, ABA Center for Pro Bono, April 28, 2004). These organizations were asked about the specific content of pro bono programs, including recruitment initiatives and the organization of program staffing and service provision, and about the number of lawyers participating. The survey report includes a measure of the total number of lawyers in each state working in organized pro bono programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor.

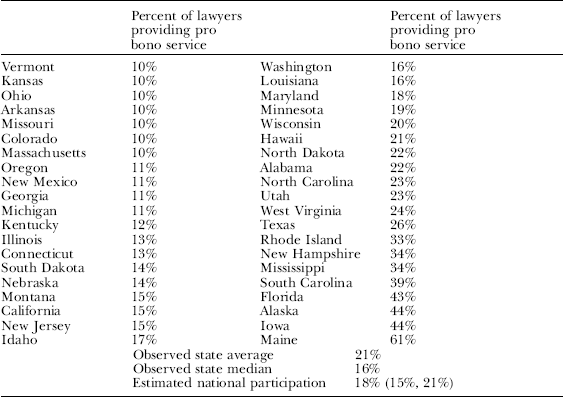

The ABA's survey of organizations and programs is the best available contemporary source of information about lawyers' participation in organized pro bono programs, but it is not perfect. Data for the survey year, 1997, are available for 40 of 50 states and the District of Columbia, and some of the survey responses reflect estimates rather than precise numbers. To the extent that this measurement error is random with respect to the variables of interest, it will tend to weaken equally the estimated relationships between pro bono activity and measures of factors that may affect it. Table 2 reports the proportion of each state's legal profession participating in civil pro bono programs in 1997, the average and median participation for states that reported pro bono participation, and the weighted estimate of the national participation rate. As the table shows, reported participation varied widely, from a low of one-tenth to a high of three-fifths. The observed state average was 21 percent; the estimate for participation in the profession nationally was 18 percent.

Table 2. Reported Lawyers' Pro Bono Activity by State and Estimated National Participation, 1997

Notes: N=40 states for which information about lawyers' participation in pro bono programs is available. States are ranked in ascending order of the reported percentage of the state legal profession participating in organized pro bono programs serving the civil legal problems of poor people. The national estimate is weighted (Reference TheilTheil 1970), and the point estimate as well as the upper and lower bounds of the 95 percent confidence interval are reported. Source: Pro Bono Delivery and Support: A Directory of Statewide Models (Center for Pro Bono 1998).

While there is measurement error in the Center report, it finds rates of pro bono participation that are highly consistent with data from surveys of individual lawyers. The most recently conducted nationally representative and publicly available survey that queried about pro bono behavior is the 1984 National Survey of Lawyers' Career Satisfaction (NSLCS) (Reference HirschHirsch 1993).Footnote 14 The NSLCS queried 2,967 lawyers, representing a response rate of 76.9 percent of the targeted stratified random sample (Reference HirschHirsch 1993: Table 4). Estimates presented herein are weighted to correct for differential sampling probabilities (Reference HirschHirsch 1993: Table 5). About their pro bono service, respondents to the NSLCS were asked,

During the past year, how many uncompensated hours have you devoted to the following public service activities either (a) as part of your job, that is your firm/employer was not compensated but these hours were considered by your employer as a legitimate part of your total hours worked, and (b) not as part of your job?

The public service activities listed included “delivery of legal services to the poor as part of [sic] organized pro bono program.” Response categories indicated the number of hours over the course of the past year the respondent had devoted to each listed activity: “none,”“1–25,”“26–74,” and “75+.” Only currently working respondents to the mail survey were asked about pro bono participation; of these 1,649 respondents, 1,391 (84 percent) responded to the pro bono question.Footnote 15

In the NSLCS, most lawyers reported work they considered pro bono, but most did not report work in organized programs serving the indigent. Four-fifths (83 percent) of surveyed lawyers reported doing work they considered pro bono, but only about one-fifth (22 percent) reported time in organized pro bono programs serving the poor in civil or criminal matters. Counting the pro bono activity of only those lawyers who reported little or no criminal work (5 percent or less of their work time in the past year) produced a more conservative estimate of 18 percent of lawyers participating in organized programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor, on par with the 18 percent participation rate estimated from the 1997 ABA survey of organizations and programs. Lawyers in the NSLCS reported working in these programs an average of 33.4 hours in the previous year.Footnote 16 Of the total number of reported hours contributed in organized pro bono programs, 82 percent were “on the clock”—that is, they were considered part of the lawyers' paid work and so were subsidized by their organizations.

Combining information about participation hours from the NSLCS with information about participation rates from the ABA survey permits construction of an estimate of the number of full-time equivalent lawyers working in organized programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor. Taking 33.4 hours as an estimate of a lawyer's average annual contribution in an organized program, about 59 volunteer lawyers are required to provide the personnel hours of one full-time employed civil legal assistance lawyer working 40 hours a week for 49 weeks a year (58.7=[40*49]/33.4). The estimated 141,000–198,000 lawyersFootnote 17 working in formally organized pro bono programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor in 1997 thus represent an estimated 2,405 to 3,368 full-time equivalent lawyers, a substantial contribution to American civil legal assistance. I turn now to an analysis of how this pro bono participation varies across states.

State-Level Pro Bono Participation

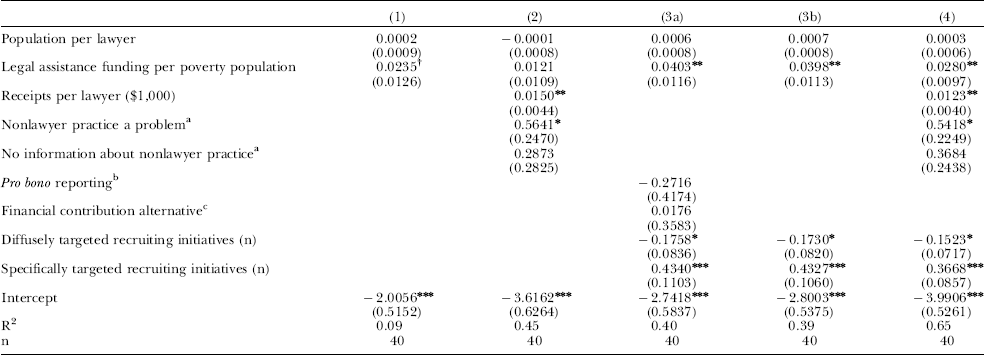

Table 3 reports the results of weighted least-squares (WLS) regressions of state pro bono participationFootnote 18 on measures of conditions in the markets for legal services and activities of the profession designed to encourage lawyers' pro bono service.Footnote 19 The first model of Table 3 constitutes a baseline, predicting participation as a function of state profession size and funding for civil legal assistance. Profession size is measured by the number of persons per private practice lawyer in the state for the year with available data closest to 1997, which happens to be 1995 (Reference CarsonCarson 1999). The theories explored in this article do not give clear a priori guidance about the expected relationship between profession size and lawyers' pro bono service. In any event, no linear relationship is observed across the values in the sample of states. The measure of funding for civil legal assistance is the total monies received from all sources, both public and private, by organizations in each state that received money from the LSC in 1997 (Legal Services Corporation 1998b). The measure included in the models scales this quantity to the size of each state's needy population, by computing dollars received per person in poverty in 1997. This quantity does not include all funding for civil legal assistance in each state, but it is the best available comparable information for the set of states. As with profession size, the theories explored in this article do not clearly imply an expected relationship. In any event, greater legal assistance funding is associated with higher rates of pro bono participation, though this relationship does not always reach conventional levels of statistical significance. The baseline model explains 9 percent of the variance in pro bono participation across states.

Table 3. State Pro Bono Service in Organized Civil Programs Serving the Poor: Metric Coefficients and Standard Errors (in parentheses) From WLS Regressions of the Logit of Participation

a Omitted category is states which reported nonlawyer practice was not an issue (Standing Committee on Lawyers' Responsibility for Client Protection 1996).

b Omitted category is states in which lawyers were not required or requested to report their annual pro bono hours in 1997.

c Omitted category is states in which the professional code regarding pro bono did not inform lawyers that financial contributions to an entity serving the poor were an acceptable substitute for pro bono service in 1997.

*** p<0.001,

** p<0.01,

* p<0.05.

† p<0.10, two-tailed tests.

Model 2 of Table 3 examines relationships between pro bono participation and conditions in the markets for legal services, net of profession size and legal assistance funding. The findings are consistent with both the cross-subsidy and interoccupational competition hypotheses. States in which the profession takes in more receipts per lawyer average higher rates of participation than states in which legal practice is less lucrative. Under the model, each $1,000 increase in receipts per lawyer is associated with a 0.6–2.4 percent increase in the odds of pro bono participation, net of profession size, legal assistance funding, and perception of the threat of unauthorized practice.Footnote 20 States in which the profession feels under threat from unauthorized practice average higher rates of participation than states in which no such threat is perceived. Under the model, perception that unauthorized practice is a problem is associated with a 6–190 percent increase in the odds of participation over states in which nonlawyer practice is not perceived as a threat. Market conditions, profession size, and legal assistance funding together explain 45 percent of the variation in participation.

Models 3a and 3b of Table 3 present estimates of relationships between pro bono and professional attempts to mobilize lawyers' service, once again controlling for profession size and legal assistance funding. The results are not consistent with the expectations of either the monitoring or the buy-out hypothesis. No relationship is observed between pro bono participation at the state level and the presence of voluntary or mandatory pro bono reporting or of a financial contribution alternative in a state's professional code. The concrete attempts of state programs to recruit lawyers do bear relationship to pro bono service. As predicted, specifically targeted initiatives—those that single out specific lawyers, law firms, or other organizations for contact—have a larger positive association with participation than diffusely targeted initiatives. Under Model 3a, each additional specifically targeted initiative is associated with a 23–93 percent increase in the odds of participation, net of profession size, legal assistance funding, and the presence of other professional initiatives. Each additional diffusely targeted initiative is associated with a 1–29 percent decrease in the odds of pro bono participation, net of profession size, legal assistance funding, and the presence of other initiatives. It is unlikely that diffusely targeted recruiting initiatives cause lawyers to do less pro bono. Rather, diffusely targeted initiatives, like the content of professional codes, may perform symbolic roles without directly encouraging lawyers' participation. The profession's pro bono initiatives, professional size, and legal assistance funding together explain 40 percent of the variance across states. As a comparison of Model 3b with Model 3a shows, the explained variance in the professional self-regulation model comes entirely from the recruiting initiatives; information about the content of professional codes adds essentially nothing (0.01=0.40–0.39) to Model 3b's ability to account for state-level variation in pro bono participation in organized civil programs.

Model 4 of Table 3 adds to the baseline model (1) both the measures of market conditions and the number of diffusely and specifically targeted recruiting initiatives. Together, these factors explain 65 percent of the variance in pro bono across states. Controlling for profession size, legal assistance funding, and recruiting initiatives, receipts per lawyer and perceived threats of unauthorized practice have positive, significant associations with pro bono service. Under Model 4, an increase of one standard deviation in receipts per lawyer (around $24,000) in an otherwise average state is associated with an additional 4.7 percent of the state profession participating in pro bono.Footnote 21 At the mean of the other variables in the model, shifting from no perception of threat from unauthorized practice to a perceived threat is associated with an additional 7 percent of the profession participating. Relationships between the number of diffusely and specifically targeted recruiting initiatives follow the same pattern as in the previous model: specifically targeted initiatives are associated with higher rates of service while, net of other factors, diffusely targeted initiatives are associated with lower rates of service. In comparison with an otherwise average state with no diffusely targeted recruiting initiatives, the average state with one such initiative exhibits an estimated 3 percent less of the profession participating in pro bono. Under the model, for an otherwise average state, the first specifically targeted recruiting initiative is associated with an additional 4 percent of the state profession providing service in organized programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor.

Discussion

The present study contributes to our understanding both of the factors that condition lawyers' pro bono work and of the structure of American-style civil legal assistance. Little positive, rather than normative, analysis of lawyers' pro bono service exists, though social scientific studies of the individual-level correlates of volunteering are extant both for the general population and for lawyers (e.g., Reference FreemanFreeman 1997; Reference SmithD. Smith 1994; Reference Wilson and MusickWilson & Musick 1997; for lawyers specifically see Reference Heinz and SchnorrHeinz, Schnorr, et al. 2001), and there is a vital literature on cause lawyering (see, e.g., Reference Heinz and PaikHeinz, Paik, et al. 2003; Reference Sarat and ScheingoldSarat & Scheingold 1998, Reference Sarat and Scheingold2001). Guided by theories of professionalism, empirical analysis of lawyers' pro bono at the level of states has produced new knowledge about pro bono in practice. A rich literature on legal aid has focused on describing and explaining the emergence of different national models of state subsidy and provision (e.g., Reference Cappelletti, Garth, Cappelletti and GarthCappelletti & Garth 1978; Reference PatersonPaterson 1991; Reference Regan and ReganRegan 1999). The present study complements and informs this work by examining the structure of legal assistance provision closer to the ground.

Analysis of the available data suggests that, in the United States in 1997, lawyers' pro bono service in organized programs serving the civil legal needs of the poor contributed substantially to civil legal assistance, providing an estimated one-quarter to almost one-third of available full-time equivalent lawyer staff. As pro bono activity and state access to justice efforts have expanded notably over the past decade while funding for the LSC has not, it is likely that this contribution has grown (Legal Services Corporation 2005; National Legal Aid and Defender Association 2005). Substantial reliance on lawyer-volunteers means that those factors that affect lawyers' pro bono participation can also affect the amount of civil legal assistance available to low-income Americans. Cross-sectional analysis of state-level variation finds that such service is unrelated to most measured attempts at professional self-regulation. Service is associated with neither the presence of “buy-out” options in professional codes nor the implementation of pro bono monitoring schemes. The most common recruitment strategies of state pro bono programs, those that are diffusely targeted and rely principally on exhortation and encouragement, are also not associated with higher rates of participation across states. Attempts to activate latent values or commitments to public service may play important symbolic roles in internal debates within the bar or in the profession's self-representation to government and to other occupations, but the state-level, cross-sectional evidence presented here does not support them as effective strategies for encouraging lawyers' service. Recruitment strategies that single out specific lawyers or firms are associated with higher rates of service. This relationship may reflect more effective overall organization of pro bono efforts or a greater commitment to pro bono in the states with more of these initiatives, as well as the effectiveness of the initiatives themselves. Conditions in state legal services markets bear strong relationships to pro bono participation. Higher revenues per lawyer are associated with greater participation in organized civil pro bono programs, as is the perception that the state's legal profession is under threat from unauthorized practice by other occupations. As suggested by market-oriented theories of lawyer professionalism, lawyers' participation in this public service activity appears highly sensitive to the dynamics of legal services markets.

While this study has produced new knowledge, it also has limitations. Among them is the fact that the analyses do not constitute a test of causal relationships; the findings may be interpreted as consistent or inconsistent with accounts of lawyers' motivations and behavior, but they cannot definitively adjudicate between them. In addition, like all studies, the present one focuses on a limited set of factors, in this case supply-side factors suggested by theories of professionalism. Other factors, including those on the demand side such as legal cultures, may also affect lawyers' pro bono participation. Finally, because the data are at the level of states, no direct information is available about which lawyers are doing pro bono work or about their motivations for doing so. Knowing who does the work and why is important both for understanding pro bono's role in legal assistance and for understanding the behavioral content of lawyer professionalism.

One important task of future research is a better understanding of how the amount and substance of available civil legal assistance are affected by pro bono participants' work settings. The present study finds that greater levels of participation are associated with higher legal services revenues and specifically targeted recruiting practices, including working with specific firms to secure their lawyers' services. Both of these findings are consistent with the observation by scholars of the “new pro bono” that large law firms play an increasingly important role in organized civil pro bono programs (Reference Boon and WhyteBoon & Whyte 1999; Reference CummingsCummings 2004). As analysis of the NSLCS revealed, in 1984, more than four-fifths (82 percent) of the total hours worked in organized pro bono were considered part of lawyers' paid work responsibilities. This represents a substantial organizational subsidy of individual lawyers' volunteer behavior. We have little quantitative information about the magnitude of large law firms' contributions relative to those from other kinds of organizations, nor do we have information about the quantitative impact of positional conflicts on the types of services available.

A second task for future research, of interest both to scholars of lawyer professionalism and to policy makers seeking to increase pro bono participation, is to understand the diversity of motives for participation across different groups of lawyers. Some observers suggest that large law firms' pro bono activity is part of a contemporary professional project pursued by elites of the organized bar and of the profession who are “reclaiming pro bono publico” from smaller practitioners (Reference Boon and WhyteBoon & Whyte 1999:170; emphasis in original). These scholars regard “[t]he entrance of large… firms into the legal aid arena” as “indicative of one segment of the profession seeking to claim that they embody [the] selfless ideal of professionalism while wishing to retain the privileges of monopoly” (Reference Noone and TomsenNoone & Tomsen 2001:26; Reference Boon and WhyteBoon & Whyte 1999; Reference CummingsCummings 2004). We know little about how this highly visible activity by large firms affects other lawyers' behavior. It may be that small practitioners and other lawyers perceive large firms' volunteer activity as absolving them of their pro bono obligations; alternatively, these lawyers may be inspired by it. Investigation of the attitudes and practices of lawyers in different organizational settings could shed light on this question (Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 2005; Reference Nelson, Trubek and NelsonNelson & Trubek 1992).

Conclusion

Avoiding the limits to service that can result from conflicts of interest and market constraints was a central goal of the founders of the federal Legal Services program. Their vision was that government-salaried lawyers, compensated by an independent third party, would be free to work diligently on behalf of their indigent clients (Reference Bamberger, Paterson and GorielyBamberger [1966]1996). This vision was never realized; for, from its inception, the federal component of American-style civil legal assistance was vulnerable to political threat (Reference AbelAbel 1985; Reference Johnson and ReganJohnson 1999; Reference Kilwein and ReganKilwein 1999). Over the past quarter-century, congressional appropriations to the LSC have declined in real terms by more than half per person eligible for services.Footnote 22 Consequently, contemporary American civil legal assistance is decentralized and reliant on philanthropy and volunteerism.

Organized pro bono is among the most important supplements to public provision. Through reliance on lawyer-volunteers, American civil legal assistance is made vulnerable to an environmental threat, conditions in legal services markets. Pro bono service becomes a “back door” through which dangers that the salaried system was intended to prevent may enter into the provision of legal aid. Reliance on pro bono renders the substance of legal assistance provision vulnerable to positional conflicts, as prior work documents, and the amount vulnerable to the dynamics of legal services markets, as the findings of the present study suggest.

American-style civil legal assistance has never aspired to ensure universal access (Reference Johnson and ReganJohnson 1999). Today, even the most comprehensive of the European welfare states are seeking ways to reorganize or scale back legal assistance in the face of fiscal constraints (Reference Blankenburg and ReganBlankenburg 1999; Reference Kilian, Moorhead and PleasenceKilian 2003; Reference Goriely, Zuckerman and CranstonGoriely 1995; Reference Moorhead, Pleasence and MoorheadMoorhead & Pleasence 2003; Reference PatersonPaterson 1991; Reference Regan and ReganRegan 1999, Reference Regan, Moorhead and Pleasence2003; Reference Zemans, Paterson and GorielyZemans [1986]1996). Other nations considering expanded use of pro bono may consider three lessons from the American experience. First, adequate service for the types of justiciable events that raise the possibility of positional conflicts may require an independent, salaried legal aid staff. The caseload of the LSC has long been and continues to be dominated by precisely those types of cases that could be served by lawyers working in pro bono programs without peril of positional conflict, family, and juvenile matters (Reference AbelAbel 1985; Legal Services Corporation 2005: Table 1).Footnote 23 Centralized client processing and volunteer coordination systems, such as those currently being developed in state access to justice efforts (National Legal Aid and Defender Association 2005), could facilitate an efficient distribution of different kinds of cases across available lawyers. To be effective, such systems would depend upon the willingness and capability of lawyers in pro bono programs to do whatever work is presented to them. Second, enlisting lawyers' organizations, as well as individual lawyers, in pro bono efforts is essential. Much pro bono in organized programs appears to be done “on the clock”—that is, lawyers are compensated by their employing organizations for their donated time. In encouraging this organizational subsidy of individual lawyers' charity, policy makers will want to be sensitive to the problem of positional conflicts. Finally, if diversified models of legal assistance provision are to be robust both to fluctuations in government and other nonprofit funding and to market conditions, they require some degree of central coordination. Unregulated reliance on charity in a market context renders service provision vulnerable to conditions in legal services markets. As this reliance expands, so does the vulnerability of American-style civil legal assistance schemes that rely heavily on private volunteers for public services.

Appendix

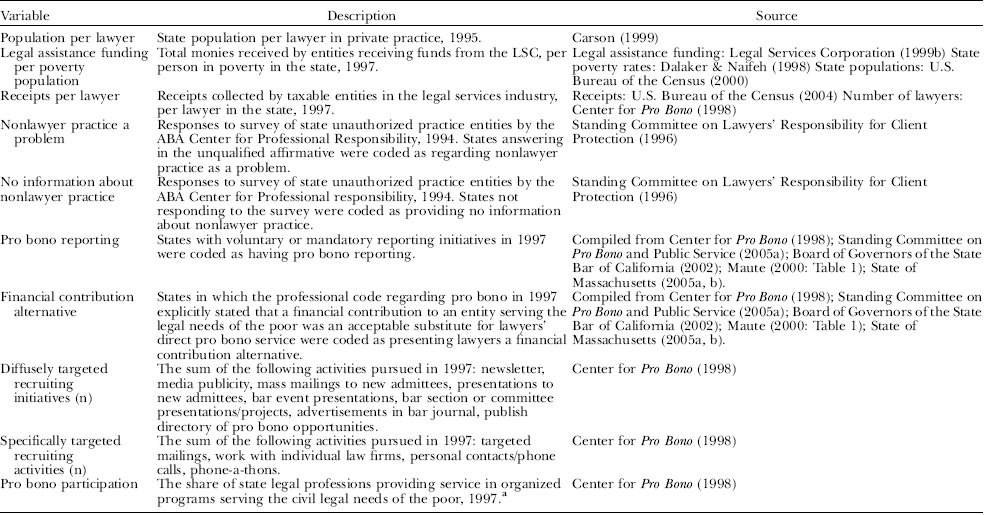

Table A1. Means and Standard Deviations and Percentages for Dichotomous Variables Included in the Regression Analyses, for the Regression Sample and the 50 States and the District of Columbia

Table A2. Descriptions and Sources of Variables Included in the Regression Analyses

a For Maryland, the pro bono figure reflects the midpoint of the estimate presented. For Texas, the pro bono figure reflects the programs' reports of participation.