Impact statement

Integrating mental health care into outpatient medical settings, such as primary care, HIV and diabetes clinics, is an effective strategy to address the tremendous global mental health treatment gap. Collaborative Care is an integrated care model with the largest evidence base supporting its effectiveness for a range of mental disorders. It involves multiple components: team-based care, structured communication between providers, tracking patient progress systematically and evidence-based treatments like pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions. However, most research around Collaborative Care has been conducted in high-income countries, where resources for health care delivery are generally more widely available than in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Without evidence to support the effectiveness of specific components of Collaborative Care models, policy makers in LMICs risk investing costly (and limited) resources in ineffective approaches. Key knowledge gaps exist regarding the effectiveness of Collaborative Care in LMICs and which specific model components are feasible and effective in LMIC settings. We conducted a rapid review literature search to address these concerns and identified 25 peer-reviewed published studies that evaluated the effectiveness of 20 models of Collaborative Care for depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorder, and epilepsy in nine different LMICs across four World Health Organization regions. Successful models shared key structural and process-of-care elements, and there was clear evidence of the importance of tailoring the model to the local context. The review extends the literature on Collaborative Care, supports its adaptability for a broad range of disorders and its dissemination to diverse settings in LMICs, and demonstrates that more work is needed to identify strategies that will support successful and sustained implementation in LMIC clinical settings.

Introduction

Mental disorders contribute significantly to morbidity, mortality and diminished quality of life throughout the world. A 2015 meta-analysis revealed that people with mental disorders have a mortality rate that is 2.22 times higher than the general population or people without mental disorders, with a decade of years of potential life lost (Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015). In 2019, depression was the second leading cause of disability worldwide, and overall, mental disorders resulted in nearly one in five years of healthy life lost due to disability (Lancet, 2020). Effective treatments exist for mental disorders, but the majority of those in need do not receive effective care (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and UnÜtzer2018; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Ahuja, Barber, Chisholm, Collins, Docrat, Fairall, Lempp, Niaz, Ngo, Patel, Petersen, Prince, Semrau, Unützer, Yueqin and Zhang2019). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), it has been estimated that 79–93% of people with depression and 85–95% of people with anxiety do not have access to treatment (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016; Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bruffaerts, Chiu, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hu, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Lund, Kovess-Masfety, Levinson, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Sampson, Scott, Tachimori, Ten Have, Viana, Williams, Wojtyniak, Zarkov, Kessler, Chatterji and Thornicroft2018). Low availability of human resources to deliver mental health services (Kakuma et al., Reference Kakuma, Minas, van Ginneken, Dal Poz, Desiraju, Morris, Saxena and Scheffler2011), stigma toward mental disorders (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Noblett, Parke, Clement, Caffrey, Gale-Grant, Schulze, Druss and Thornicroft2014), and poor implementation of mental health programs at scale contribute to this large unmet need for mental health care (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, McCay, Semrau, Chatterjee, Baingana, Araya, Ntulo, Thornicroft and Saxena2011). Globally, existing mental health services have limited capacity to address the burden of mental disorders, and the majority of mental health care is provided at the primary care level (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar, Bordin, Costello, Durkin, Fairburn, Glass, Hall, Huang, Hyman, Jamison, Kaaya, Kapur, Kleinman, Ogunniyi, Otero-Ojeda, Poo, Ravindranath, Sahakian, Saxena, Singer, Stein, Anderson, Dhansay, Ewart, Phillips, Shurin and Walport2011).

Building capacity for mental health treatment within primary care and other medical settings where people already seek care is an efficient strategy for increasing access to effective mental health treatment (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Ahuja, Barber, Chisholm, Collins, Docrat, Fairall, Lempp, Niaz, Ngo, Patel, Petersen, Prince, Semrau, Unützer, Yueqin and Zhang2019). Individuals living with chronic medical conditions (such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus [HIV] and noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension) have significantly higher rates of common mental disorders (Moussavi et al., Reference Moussavi, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun2007), and regular care for these conditions provides medical practitioners opportunities to identify and engage people with comorbid medical and mental disorders in care (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Ahuja, Barber, Chisholm, Collins, Docrat, Fairall, Lempp, Niaz, Ngo, Patel, Petersen, Prince, Semrau, Unützer, Yueqin and Zhang2019). Integrating care for mental disorders into primary or secondary medical care can reduce the fragmentation and complexity of care, creating an opportunity for a more person-centered healthcare experience (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Meller, Kishi and Kathol2014). Integrated care can facilitate screening for mental disorders, and increase the likelihood that people will connect to the care they need. Because integrated care models have the potential to improve quality of life, self-care, adherence to medical and mental health treatments, and both mental and physical disease outcomes (Coates et al., Reference Coates, Coppleson and Schmied2020), the World Health Organization (WHO) promotes the integration of mental health services into primary health care as a feasible strategy to address the treatment gap (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar, Bordin, Costello, Durkin, Fairburn, Glass, Hall, Huang, Hyman, Jamison, Kaaya, Kapur, Kleinman, Ogunniyi, Otero-Ojeda, Poo, Ravindranath, Sahakian, Saxena, Singer, Stein, Anderson, Dhansay, Ewart, Phillips, Shurin and Walport2011).

There are myriad approaches to integrating mental health care and primary medical care. Without evidence to support the effectiveness of specific models or approaches, policy makers risk investing costly (and limited) resources in ineffective approaches. A 2020 scoping review identified 37 models of integrated physical and mental health care published in medical literature. These models shared several key characteristics, including colocated care delivered by a multi-disciplinary team, a joint treatment plan with structured communication, and care coordination (Coates et al., Reference Coates, Coppleson and Schmied2020). Among integrated care models, the largest body of research evidence supports Collaborative Care, a complex multi-component model which applies the principles of the chronic care model (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Austin and Von Korff1996) to integrate evidence-based mental health treatment into outpatient medical settings. In Collaborative Care, primary medical physicians work with a care manager and a consulting psychiatrist to proactively identify, treat, and monitor people with mental disorders (Katon, Reference Katon2012). Key elements include population-based patient identification; continual symptom monitoring using an electronic registry; measurement-based care to track treatment response and a stepped-care approach to systematically adjust treatment for patients who are not improving or meeting measurement-based targets (Katon et al Reference Katon2012). Collaborative Care models are distinguished from other integrated care models by these core components of population-based care, measurement-based care, and delivery of evidence-based mental health services (McGinty and Daumit, Reference McGinty and Daumit2020; Yonek et al., Reference Yonek, Lee, Harrison, Mangurian and Tolou-Shams2020).

The Collaborative Care model was initially designed to improve depression outcomes in primary care (Unützer et al., Reference Unützer, Katon, Callahan, Williams, Hunkeler, Harpole, Hoffing, Della Penna, Noël, Lin, Areán, Hegel, Tang, Belin, Oishi, Langston and Investigators2002), but over the past 20 years, it has been adapted and implemented in a wide range of mental disorders (e.g., PTSD and bipolar disorder) (Zatzick et al., Reference Zatzick, Roy-Byrne, Russo, Rivara, Droesch, Wagner, Dunn, Jurkovich, Uehara and Katon2004; Fortney et al., Reference Fortney, Bauer, Cerimele, Pyne, Pfeiffer, Heagerty, Hawrilenko, Zielinski, Kaysen, Bowen, Moore, Ferro, Metzger, Shushan, Hafer, Nolan, Dalack and Unützer2021), populations (e.g., primary care patients with diabetes) (Katon et al., Reference Katon, Lin, Von Korff, Ciechanowski, Ludman, Young, Peterson, Rutter, McGregor and McCulloch2010) and settings (e.g., maternal and child health clinics [Katon et al., Reference Katon, Russo, Reed, Croicu, Ludman, LaRocco and Melville2014; Grote et al., Reference Grote, Katon, Russo, Lohr, Curran, Galvin and Carson2015] and HIV clinics) (Pyne et al., Reference Pyne, Fortney, Curran, Tripathi, Atkinson, Kilbourne, Hagedorn, Rimland, Rodriguez-Barradas, Monson, Bottonari, Asch and Gifford2011). More than 80 randomized controlled trials demonstrate Collaborative Care’s effectiveness for a range of mental disorders for diverse populations and settings (Archer et al., Reference Archer, Bower, Gilbody, Lovell, Richards, Gask, Dickens and Coventry2012). Efforts to scale the Collaborative Care model in primary care settings, however, have not yet translated into widespread uptake or significant population health gains (McGinty and Daumit, Reference McGinty and Daumit2020). Implementation of Collaborative Care involves substantial practice change in the medical setting. Collaborative Care models introduce both structural elements (data tracking tools and new staff, including a care manager and a psychiatric consultant) and process-of-care elements (measurement-based care (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Boyd, Puspitasari, Navarro, Howard, Kassab, Hoffman, Scott, Lyon, Douglas, Simon and Kroenke2019) and systematic caseload review (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Williams, Ratzliff and Unützer2019) to the clinical setting (McGinty and Daumit, Reference McGinty and Daumit2020). Research suggests that tailoring evidence-based interventions to fit the clinical context is associated with increased likelihood of implementation success (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Cabassa and Sitrman2017). Across research and implementation studies in high-income countries (HICs), the Collaborative Care model core principles have been operationalized as a wide range of model components.

Less is known about whether the core components of the Collaborative Care model are feasible or effective in LMICs (Cubillos et al., Reference Cubillos, Bartels, Torrey, Naslund, Uribe-Restrepo, Gaviola, Díaz, John, Williams, Cepeda, Gómez-Restrepo and Marsch2021). Increased understanding of successful Collaborative Care models – including specific model components – is vital for policy makers and healthcare systems which seek to implement Collaborative Care to increase access to mental health care and improve outcomes in their populations (Overbeck et al., Reference Overbeck, Davidsen and Kousgaard2016; Acharya et al., Reference Acharya, Ekstrand, Rimal, Ali, Swar, Srinivasan, Mohan, Unützer and Chwastiak2017). A 2021 systematic review of integrated care models in LMICs identified six experimental or nonexperimental studies published between 1990 and 2017 that evaluated the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of Collaborative Care models for depression and/or unhealthy alcohol use in LMICs (Cubillos et al., Reference Cubillos, Bartels, Torrey, Naslund, Uribe-Restrepo, Gaviola, Díaz, John, Williams, Cepeda, Gómez-Restrepo and Marsch2021). Building on these findings, we conducted a rapid review (Garritty et al., Reference Garritty, Gartlehner, Nussbaumer-Streit, King, Hamel, Kamel, Affengruber and Stevens2021) to extend the search to several mhGAP priority mental disorders and to identify more recent studies that evaluate Collaborative Care in primary or secondary outpatient medical settings in LMICs. The primary aim of this review is to describe effective Collaborative Care models that have been evaluated in LMICs and the “successful ingredients” of these models to help inform implementation by health care systems and policy makers and identify areas for future research.

Methods

We conducted a rapid review following guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group on conducting rapid reviews (Garritty et al., Reference Garritty, Gartlehner, Nussbaumer-Streit, King, Hamel, Kamel, Affengruber and Stevens2021), and used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) to guide our review (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021). The protocol was registered on Open Science Framework (registration DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/FJ79U).

Electronic search strategy and sources

Our literature search strategy was informed by knowledge of the literature, discussion with knowledge experts in the field, and detailed review of published search strategies from similar literature reviews (Yonek et al., Reference Yonek, Lee, Harrison, Mangurian and Tolou-Shams2020; Cubillos et al., Reference Cubillos, Bartels, Torrey, Naslund, Uribe-Restrepo, Gaviola, Díaz, John, Williams, Cepeda, Gómez-Restrepo and Marsch2021). In consultation with two authors (L.C. and J.W.), a university health sciences librarian (T.J.) iteratively developed the search string and strategy, which were reviewed according to guidelines from Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) (McGowan et al., Reference McGowan, Sampson, Salzwedel, Cogo, Foerster and Lefebvre2016). A full description of the search strategy can be found in Supplementary Material. Key search terms were developed using the following sources: (1) LMIC (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care LMIC filter) and (2) integrated care (International Foundation of Integrated Care) (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Damarell, Tieman and Trenerry2018).

Our electronic search was conducted on May 23, 2022, in five databases, selected due to their focus on general medical, psychiatric and global literature: (1) PubMed, (2) Embase, (3) Global Index Medicus, (4) PsycInfo and (5) Cochrane Central. Our search was performed without language restrictions.

Eligibility criteria

We searched for experimental and nonexperimental studies that examined the effectiveness of a Collaborative Care model on the management of any mental disorder in primary or secondary healthcare in LMICs. Included mental disorders were priority adult mental disorders in the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) intervention guidelines (World Health Organization, 2016), which included depression, psychosis, substance use disorders, other (including anxiety and PTSD), and epilepsy (in most LMICs, epilepsy is considered a psychiatric condition and is treated by mental health specialists) (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Luitel, Kohrt, Rathod, Garman, De Silva, Komproe, Patel and Lund2019). Articles eligible for inclusion were required to meet the following criteria: (1) studies included patients aged ≥18 years, of any gender and with a diagnosis of mental disorder of any severity; (2) studies performed with a population living in LMICs as per the World Bank country income classification (The World Bank, 2022 , List of Low-and Middle-Income Countries) during the year the study started; (3) studies included patients who received mental health services in an outpatient medical setting (primary or secondary health care); (4) experimental, quasi-experimental and nonexperimental study designs that reported clinical outcomes and involved a comparison group and (5) studies included Collaborative Care models, we defined to be consistent with the typology of the 2021 systematic review of integrated care models in LMICs (Cubillos et al., Reference Cubillos, Bartels, Torrey, Naslund, Uribe-Restrepo, Gaviola, Díaz, John, Williams, Cepeda, Gómez-Restrepo and Marsch2021): a multicomponent, highly coordinated, team-based approach to providing mental health care with systematic integration into outpatient medical settings, with an interdisciplinary team comprised of at least a primary medical provider and a mental health care manager collaborating to systematically track patient progress and deliver evidence-based care, including pharmacotherapy, care coordination and/or brief behavioral interventions. We excluded studies that did not report clinical effectiveness outcomes, and cohort studies that reported outcomes but did not have a comparison group. We also excluded presentations, abstracts, corrections and nonpeer-reviewed papers. There were no exclusions based on language.

Article review and selection

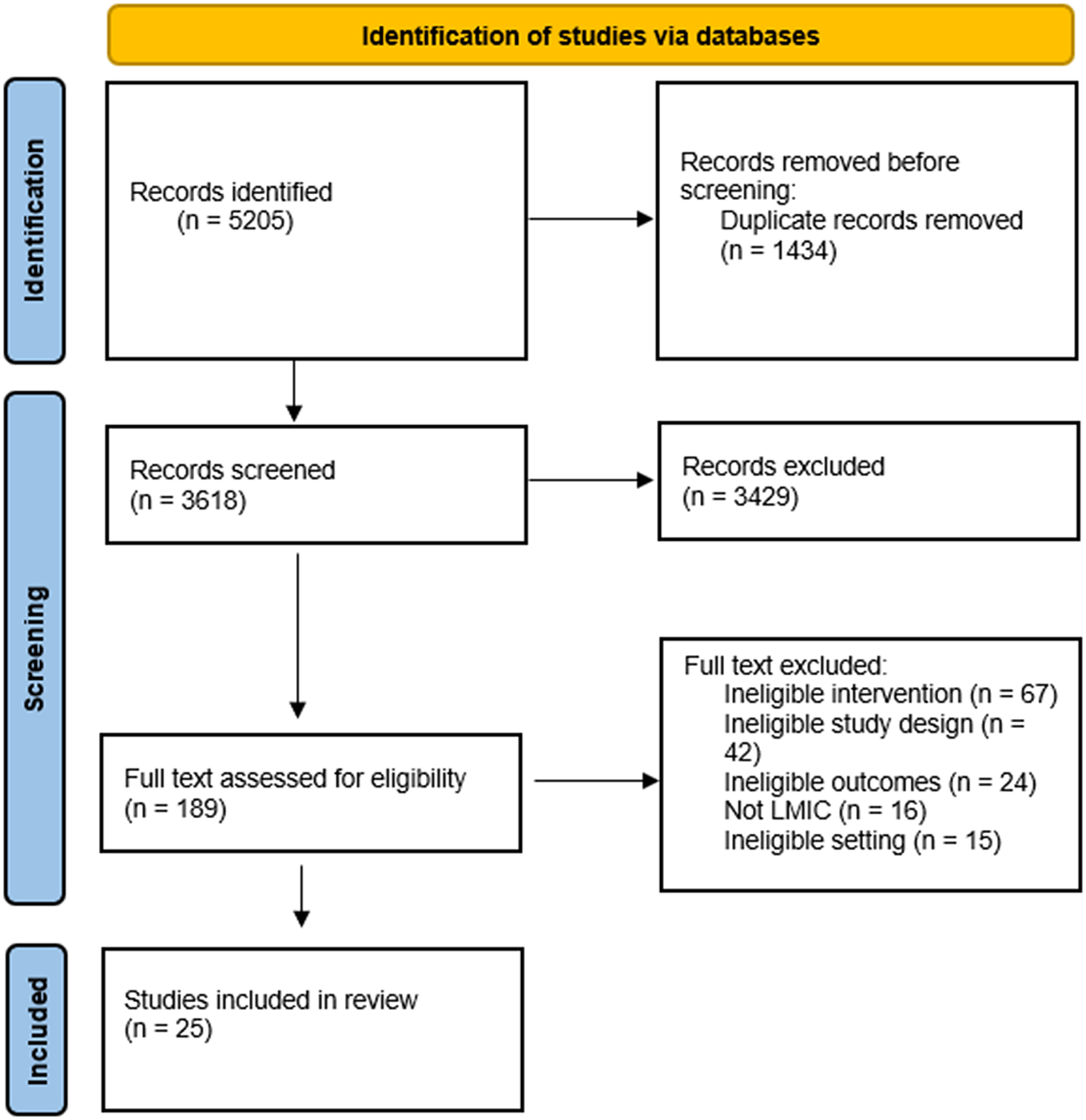

Article abstracts were uploaded and reviewed using Covidence Review Software. Figure 1 describes the PRISMA systematic process for article selection. Upon uploading the initial search results, Covidence automatically screened for and removed duplicate articles. Following Cochrane recommendations for rapid reviews (Garritty et al., Reference Garritty, Gartlehner, Nussbaumer-Streit, King, Hamel, Kamel, Affengruber and Stevens2021), each title and abstract was reviewed by one of the authors (J.W., S.O., A.B., B.F. and L.C.) and all excluded abstracts were reviewed again by a second author (J.W. or L.C.). Duplicates missed by Covidence’s automatic process were manually marked as duplicate at this stage. Articles that met eligibility criteria and those that were inconclusive from the abstract review were included for full-text review. Protocol papers and review papers that were identified in the search were compiled and reviewed by two authors (J.W. and L.C.) to identify additional studies to include. Four authors (J.W., L.C., B.F. and S.O.) conducted full-text reviews of the studies deemed eligible based on title and abstract review. As in the title and abstract screening, articles that were excluded at this stage were reviewed by a second author and conflicts were resolved through iterative communication or discussion with the senior author (L.C.).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of studies screened and included in data extraction.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by the two authors (J.W. and L.C.) utilizing a custom data extraction form in Covidence. Extracted data included: (1) study characteristics, including publication year, location (country), study design, number of participants, target mental disorder(s), and comparison treatment; (2) target population and participant characteristics; (3) intervention characteristics and model components, intervention duration; (4) primary and secondary outcomes and (5) key findings. For studies with more than one associated article, the primary article was cited as the main reference, although data were extracted from all available articles. The authors’ extraction forms were compared for consistency and any differences were resolved by discussion. Components of the Collaborative Care model in each study were tracked using an intervention component checklist in the Covidence data extraction form. Model components in the intervention checklist were informed by the key components of Collaborative Care, developed by Kroenke and Unutzer (Reference Kroenke and Unutzer2017): mental health screening, psychiatric consultant, care manager, pharmacotherapy, measurement-based care, treatment to target, registry, brief behavioral intervention, care coordination, psychoeducation, systematic case review, systematic team communication, referral process for specialty care or stepped care. We considered a model component to be present if it was specifically mentioned, regardless of the level of detail reported.

Assessment and synthesis

Two authors (S.O. and L.C.) independently assessed the quality of studies, using Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool version 2.0 (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe, Boutron, Cates, Cheng, Corbett, Eldridge, Emberson, Hernán, Hopewell, Hróbjartsson, Junqueira, Jüni, Kirkham, Lasserson, Li, McAleenan, Reeves, Shepperd, Shrier, Stewart, Tilling, White, Whiting and Higgins2019) for randomized controlled trials and the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Nonrandomized Studies – of Interventions) (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Hernan, Reeves, Savovic, Berkman and Viswanathan2016) for nonrandomized studies. Discrepancies were reconciled through discussion. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize study characteristics. To synthesize the evidence supporting model components, we identified the key components within effective multicomponent interventions (Table 2) and aggregated this information across interventions to examine how frequently the components were applied (Table 3; Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Becker and Daleiden2007; Yonek et al., Reference Yonek, Lee, Harrison, Mangurian and Tolou-Shams2020).

Results

Our search yielded 5,205 articles, from which 1,434 duplicates were removed, leaving 3,618 titles and abstracts to be reviewed. Of these, 189 were included for a full-text review. After full-text review, 25 studies met inclusion criteria, of which 20 were RCTs and 5 were cohort studies with comparison groups. We did not include for data extraction two pilot studies with subsequent RCTs that met our inclusion criteria (Oladeji et al., Reference Oladeji, Kola, Abiona, Montgomery, Araya and Gureje2015; Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Adewumi, Momodu, Olibamoyo, Adesoji, Adegbokun, Adeyemo, Manuwa and Adegbaju2019a).

Overview of included studies

Our search identified 25 studies (randomized controlled trials or nonrandomized studies with comparison groups), which described 20 Collaborative Care models. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1. Twenty studies (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010, Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2011; Pradeep et al., Reference Pradeep, Isaacs, Shanbag, Selvan and Srinivasan2014; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Indu et al., Reference Indu, Anilkumar, Vijayakumar, Kumar, Sarma, Remadevi and Andrade2018; Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Momodu, Olibamoyo, Adegbaju, Adesoji and Adegbokun2019b,Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomalec; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a,Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Arayab; Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021; Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Keyes and Susser2021; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022; Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Johnson, Sagar, Poongothai, Tandon, Anjana, Aravind, Sridhar, Patel, Emmert-Fees, Rao, Narayan, Mohan, Ali and Chwastiak2022; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022) were from RCTs (primary or secondary analyses) that evaluated 16 unique models; five cohort studies (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017, Reference Jordans, Garman, Luitel, Kohrt, Lund, Patel and Tomlinson2020; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Aldridge et al., Reference Aldridge, Garman, Luitel and Jordans2020) evaluated an additional four Collaborative Care models. Publication dates ranged from 2010 to 2022, and sample sizes ranged from 60 patients to 2,796 patients. Nine of these models were tested in the African Region (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a, Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Arayab; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019, Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022), eight in the South-East Asian Region (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Pradeep et al., Reference Pradeep, Isaacs, Shanbag, Selvan and Srinivasan2014; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017, Reference Jordans, Garman, Luitel, Kohrt, Lund, Patel and Tomlinson2020; Indu et al., Reference Indu, Anilkumar, Vijayakumar, Kumar, Sarma, Remadevi and Andrade2018; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022), two in the Western Pacific Region (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019), and one in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019). No studies were conducted in LMICs in the European Region or the Region of the Americas. (Asher et al Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022; Stockton et al Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Wagner et al Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016).

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of included randomized controlled trials and cohort studies

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; ART, antiretroviral therapy; BPRS-E, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale-Expanded; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions Scale; CIS-R, Clinical Interview Scale-Revised; Epilepsy-9, 9-item instrument re: the number epileptic seizures in the previous 3 months; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 item scale; GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire 28 items; GRIMS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTN, hypertension; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PHQ9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item; SCL-20, Symptom Checklist-20 item; TB, tuberculosis; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

a Follow-up duration the same as primary outcome unless otherwise noted.

b Primary outcome of comparison between Collaborative Care intervention and Collaborative Care intervention with mobile telephony support.

c Secondary analyses.

d Noninferiority trial.

Among the models with RCT evidence, 10 demonstrated improvement in the primary outcome (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Indu et al., Reference Indu, Anilkumar, Vijayakumar, Kumar, Sarma, Remadevi and Andrade2018; Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022); 5 did not (Pradeep et al., Reference Pradeep, Isaacs, Shanbag, Selvan and Srinivasan2014; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021). One study compared a high-intensity intervention to a low-intensity intervention; both interventions improved clinical outcomes, but there was no additional benefit to the high-intensity intervention (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a). All four cohort studies demonstrated improved clinical outcomes among patients who received Collaborative Care when compared to the comparison group.

The majority of models were tested in general primary care settings, but two were tested in outpatient HIV clinics/treatment centers (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020), one in diabetes specialty clinics (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020) and two in maternal health clinics (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019). Seventeen of the 20 models targeted depression, with three that focused on maternal/perinatal depression (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019), and one on geriatric depression (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015). Five models targeted either schizophrenia or psychosis or more serious mental disorders (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022), three targeted alcohol use disorder (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Garman, Luitel, Kohrt, Lund, Patel and Tomlinson2020), and one targeted epilepsy (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017). Three models either targeted anxiety disorders or were shown to have positive impact on anxiety (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Johnson, Sagar, Poongothai, Tandon, Anjana, Aravind, Sridhar, Patel, Emmert-Fees, Rao, Narayan, Mohan, Ali and Chwastiak2022; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022). No studies addressed PTSD or substance use disorders other than alcohol. Primary outcomes for the studies were validated clinical rating scales in 17 of the studies, disability for 3 studies, and treatment or medication adherence for 4 studies. The most common measures were Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) for depression, WHO Disability Assessment Scale II (WHODAS II) (Chwastiak and Von Korff, Reference Chwastiak and Von Korff2003) for disability, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987) for schizophrenia, and AUDIT-C (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, DeBenedetti, Volk, Williams, Frank and Kivlahan2007) for alcohol use disorder.

Fourteen of the studies reported the primary results of randomized controlled trials. Nine of these were positive studies (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Indu et al., Reference Indu, Anilkumar, Vijayakumar, Kumar, Sarma, Remadevi and Andrade2018; Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022), and eight were assessed to have low risk of bias. One positive trial was stopped early (at 12 months rather than the planned 24) and missing data were not imputed, introducing the potential for bias (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015). Among the five RCTs that did not have a significant impact on the primary outcome (Pradeep et al., Reference Pradeep, Isaacs, Shanbag, Selvan and Srinivasan2014; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021), there was concern of risk of bias in favor of the comparison condition in one of the studies. This pragmatic study may have been impacted by the cointervention of concentrating referral specialist mental health services in the control clinics to improve service coverage in the district (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021). The Stockton trial was assessed to have low risk of bias (and included intent-to-treat analyses), but authors noted that few participants received an adequate dose of either pharmacotherapy or the psychological intervention (Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020). Four of the five included nonrandomized cohort studies recruited comparison samples from patients who had screened positive as part of the intervention workflow, but whose diagnosis was not detected by the medical provider (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Aldridge et al., Reference Aldridge, Garman, Luitel and Jordans2020; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Garman, Luitel, Kohrt, Lund, Patel and Tomlinson2020). This may have introduced of bias in favor of the intervention as the screening interview may have heightened patient awareness of their symptoms.

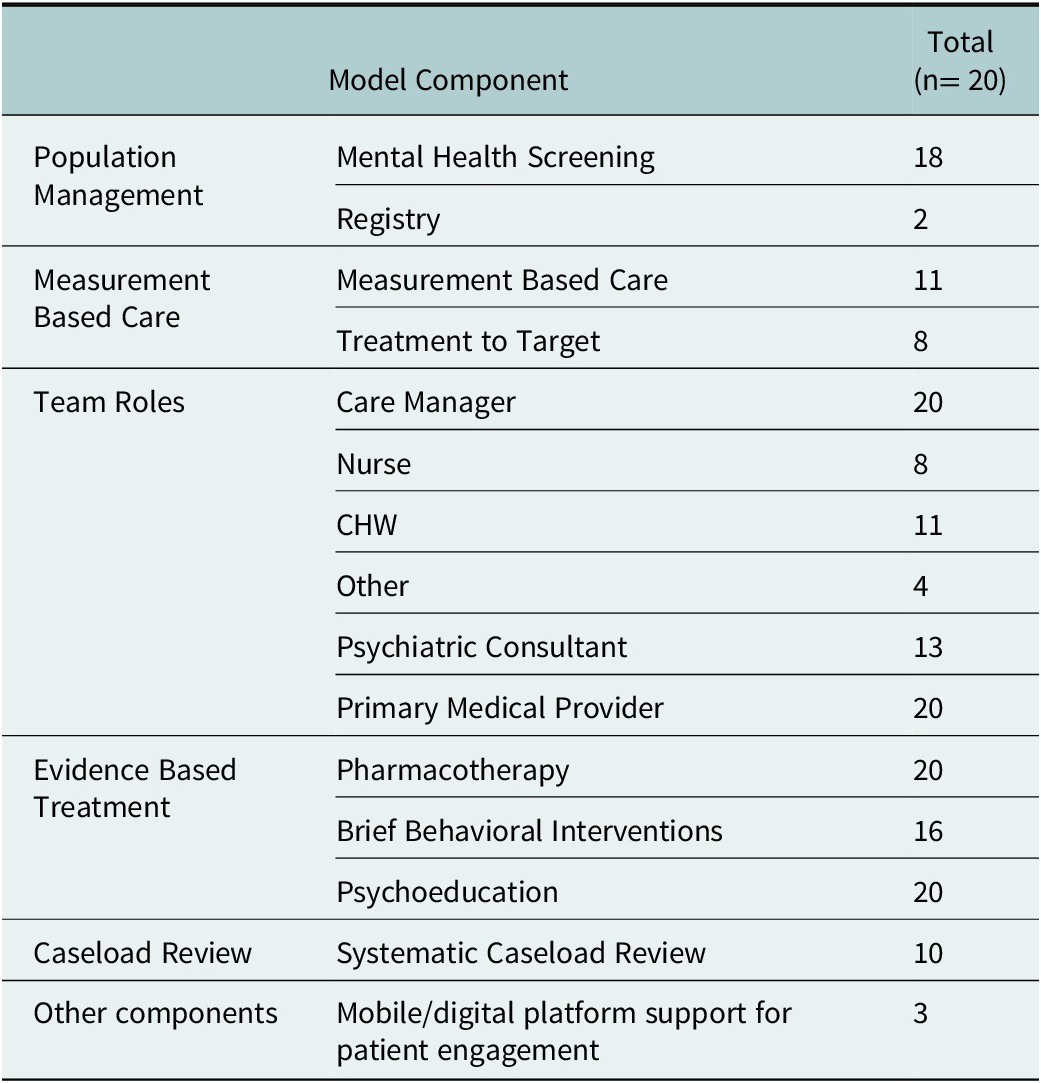

Components of Collaborative Care models

Table 2 provides an overview of the models and components for the included studies, and Table 3 summarizes the frequencies of each of these components across models from these studies. Team-based care is a required component of Collaborative Care, but the models varied with respect to the composition of the team. In nine models, the care manager role was filled by a lay health worker or community health worker (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Pradeep et al., Reference Pradeep, Isaacs, Shanbag, Selvan and Srinivasan2014; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017, Reference Jordans, Garman, Luitel, Kohrt, Lund, Patel and Tomlinson2020; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019; Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022); nurses filled the role in four other models (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Indu et al., Reference Indu, Anilkumar, Vijayakumar, Kumar, Sarma, Remadevi and Andrade2018; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022). Four models utilized other clinical staff, including midwives (Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Noorbala et al., Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019), other maternal health care providers (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a), or allied health professionals working in diabetes clinics (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020). The roles and tasks of care managers were split across multiple team members in four of the models (Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019, Reference Petersen, Fairall, Zani, Bhana, Lombard, Folb, Selohilwe, Georgeu-Pepper, Petrus, Mntambo, Kathree, Bachmann, Levitt, Thornicroft and Lund2021; Asher et al., Reference Asher, Birhane, Weiss, Medhin, Selamu, Patel, De Silva, Hanlon and Fekadu2022). Thirteen studies included a consulting psychiatrist who provided regular consultation to either the care manager, the primary care physician or both; frequency of consultation ranged from every week to every month (Adewuya et al Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Ali et al Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Chen et al Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Hanlon et al Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Prince, Assefa, Shibre, Ejigu, Negussie, Timothewos, Schneider, Thornicroft, Wissow, Susser, Lund, Fekadu and Alem2022; Jordans et al Reference Jordans, Aldridge, Luitel, Baingana and Kohrt2017; Noorbala et al Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Patel et al Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Shidaye et al Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Srinivasan et al Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022; Wagner et al Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Xu et al Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019). Two models included a pharmacist or pharmacy technician on the Collaborative Care team (Adewuya et al., Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Srinivasan et al., Reference Srinivasan, Heylen, Johnson Pradeep, Mony and Ekstrand2022).

Table 2. Summary of published components of Collaborative Care models

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CBR, community-based rehabilitation; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CHEW, community health extension workers; CHW, community health workers; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire 28 items; GRIMS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State; LHC, lay health counselors; MHFA, mental health first aid; mhGAP, Mental Health Gap Programme; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PCP, primary care physician; PHQ2, Patient Health Questionnaire 2 item; PHQ9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item; PST, problem-solving therapy.

All models included evidence-based treatments for the target mental disorder. In all cases, this included pharmacotherapy, which was supported by mhGAP or national treatment guidelines. One study included electronic decision support within the medical record to support physician prescribing (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020). Psychoeducation or brief psychological interventions were included in all studies, either in individual or group format; and in all models, these were delivered by the care manager. Behavioral activation and Problem-Solving Therapy were the most common brief psychological interventions for studies of depression. All models described training and supervision protocols, highlighting the critical need for staff and resources for these activities.

Population management components commonly included universal/ routine screening for the target mental disorder and specific strategies for outreach to patients who were not engaged in care. Fourteen of the 20 models provided specifics about a stepped approach to care: measurement at specified time intervals with treatment intensification (either increase in number of sessions of psychological intervention, combination of pharmacotherapy and psychological intervention; or referral to mental health specialist) (Table 2). The greatest variation across studies was with respect to how measurement was incorporated into the clinical workflow. Eleven studies explicitly described measurement-based care, that is, regularly scheduled follow-up by the care manager and regular tracking of a validated clinical outcome measure (Adewuya et al Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Ali et al Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Chen et al Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Noorbala et al Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Patel et al Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Shidaye et al Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019; Stockton et al Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020; Wagner et al Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Xu et al Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019). Treatment-to-target, though, was present in fewer than half of the studies (Adewuya et al Reference Adewuya, Ola, Coker, Atilola, Fasawe and Ajomale2019c; Ali et al Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020; Chen et al Reference Chen, Conwell, He, Lu and Wu2015; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Bello, Kola, Ojagbemi, Chisholm and Araya2019b; Noorbala et al Reference Noorbala, Afzali, Abedinia, Akhbari, Moravveji and Shariat2019; Patel et al Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Shidaye et al Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019). Only two studies described the use of a registry to support the clinical workflow (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Ghosh-Dastidar, Ngo, Robinson, Musisi, Glick and Dickens2016; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Chwastiak, Poongothai, Emmert-Fees, Patel, Anjana, Sagar, Shankar, Sridhar, Kosuri, Sosale, Sosale, Rao, Tandon, Narayan and Mohan2020). Few models included mobile or digital support systems to support patient communication and engagement (Adewuya et al Reference Adewuya, Momodu, Olibamoyo, Adegbaju, Adesoji and Adegbokun2019b; Gureje et al Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm, Groleau, Kirmayer, Kola, Olley, Tan and Zelkowitz2019a; Xu et al Reference Xu, Xiao, He, Caine, Gloyd, Simoni, Hughes, Nie, Lin, He, Yuan and Gong2019) (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of frequencies of Collaborative Care model components

Abbreviations: CHW, community health worker

Discussion

This rapid review supports the effectiveness of Collaborative Care models to treat a wide range of mental disorders in diverse outpatient medical settings in LMICs. We identified 25 randomized controlled trials or cohort studies with comparison groups which evaluated the effectiveness of 20 Collaborative Care models to treat common mental disorders, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorder, or epilepsy in nine different LMICs. Fourteen of the 20 Collaborative Care models had statistically significant improved clinical outcomes compared to usual primary care. Clinical outcomes were primarily validated rating scales of symptom severity or disability. More recent studies, specifically models that provided treatment for schizophrenia, highlighted the critical need to address social determinants of health, monitor functional outcomes, and link clinic-based care with community- or family-based services. Effectiveness data from randomized controlled trials, however, was limited to studies of common mental disorders (depression and anxiety) or schizophrenia. No RCT of Collaborative Care interventions for substance use disorders, epilepsy or post-traumatic stress disorder were identified.

Despite differences in staffing and resources across the clinical settings in these studies, each of these models operationalized the same core principles of effective Collaborative Care that are described in studies in HIC (Sighinolfi et al., Reference Sighinolfi, Nespeca, Menchetti, Levantesi, Belvederi Murri and Berardi2014; Muntingh et al., Reference Muntingh, van der Feltz-Cornelis, van Marwijk, Spinhoven and van Balkom2016; Dham et al., Reference Dham, Colman, Saperson, McAiney, Lourenco, Kates and Rajji2017; Yonek et al., Reference Yonek, Lee, Harrison, Mangurian and Tolou-Shams2020). As in HIC studies, effective models shared several structural and process-of-care elements. Structural elements included a multi-disciplinary care team and standardized protocols for the delivery of evidence-based (pharmacologic and/or brief psychological intervention). Shared process-of-care elements included proactive and systematic identification of mental disorders, team-based care with structured communication, and longitudinal measurement of patient response to treatment and a stepped-care approach to intensify treatment when measurements show that a patient is not improving as expected. Some core components of Collaborative Care models implemented in HIC were less frequently described in these LMIC studies. Specifically, relatively few models described rigorous measurement-based care and the systematic use of a registry to support the clinical workflow.

There was, however, substantial heterogeneity across models and their components. This is consistent with experience in implementation of other evidence-based interventions that there is a need to tailor interventions for specific target populations and clinical contexts (Wiltsey Stirman et al., Reference Wiltsey Stirman, Kimberly, Cook, Calloway, Castro and Charns2012). For example, a wide range of disciplines performed the role of the care manager, and the frequency and modes of team communication ranged widely. Almost all studies included psychiatric expertise on the multi-disciplinary team, and a regular structured meeting to review the caseload of patients was typical of the effective models. In addition, linkage to community resources is a core component of Collaborative Care models, but specific tasks and workflows were dependent on the specific context. Several of the studies highlighted that tailoring the model to both culture and clinical context was critical for its effectiveness (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Johnson, Sagar, Poongothai, Tandon, Anjana, Aravind, Sridhar, Patel, Emmert-Fees, Rao, Narayan, Mohan, Ali and Chwastiak2022). Several studies described how Collaborative Care can promote culturally appropriate care, and that collaborations with other community sectors can address social and economic determinants of mental health.

The review extends the literature on Collaborative Care and supports its adaptability for a broad range of disorders and its dissemination to diverse settings in LMICs. The identification of components that are shared across effective models advances our understanding of what may be essential for successful implementation, which is useful information for policy makers in planning to scale Collaborative Care (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Cubillos, Uribe-Restrepo, Suárez-Obando, Meier, Naslund, Bartels, Williams, Cepeda, Torrey, Marsch and Gómez-Restrepo2020). The review also provides pragmatic information about alternative strategies for operationalizing model components based on local resources. Several of the included studies highlight the resources and planning that are required to translate a Collaborative Care model from research studies into care provided in routine clinical settings. It is not trivial, for example, to repurpose existing clinical staff to be Collaborative Care team members, but such role expansion could increase the potential sustainability of a Collaborative Care program (Stockton et al., Reference Stockton, Udedi, Kulisewa, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Mphonda, Maselko, Pettifor, Verhey, Chibanda, Lapidos-Salaiz and Pence2020). Similarly, mental health outcome tracking could be more efficient if it is integrated into the general medical information system and workflows (Ndetei and Jenkins, Reference Ndetei and Jenkins2009).

Process evaluations of several of the RCTs provide valuable insights into potential barriers and facilitators to the implementation of these Collaborative Care models. Insight into processes that work well within specific contexts can lead to increased uptake of Collaborative Care models and their capacity to address the mental health treatment gap in LMICs. Adequate training and supervision of team members are essential to facilitate implementation (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Mntambo, Weiner, Grant, Rao, Bhana, Gigaba, Luvuno, Simoni, Hughes and Petersen2021), including training to work as a team and fostering a shared vision of the work (Li et al., Reference Li, Xue, Conwell, Yang and Chen2020). Second, new tasks must be appropriate to the skills of team members and easily integrated into their existing practices. Studies that incorporated screening by clinical staff as part of routine care (rather than by research staff) highlight that this critical first step must be successful in order to achieve improved population-level outcomes – that is, that even very effective models will have limited impact if they reach very few people who need treatment (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava, Lund and Patel2019). A 2020 review of barriers and facilitators to integrated care in LMICs highlights additional health system challenges that critically impact implementation, such as scarcity of strong leadership, lack of leadership buy-in, and mismanaged information systems (Esponda et al., Reference Esponda, Hartman, Qureshi, Sadler, Cohen and Kakuma2020).

Several strengths of this rapid review increase the impact of the findings. Rigorous methods were utilized, following guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group. In addition, the review included studies related to the adult mhGAP priority mental disorders and also studies in outpatient settings beyond primary care, thus increasing the generalizability of the findings. Some limitations of this review should also be acknowledged. First, the presence of multiple components in effective models does not provide information about which (or whether) specific components are required for effectiveness. Second, because multiple disorders and heterogeneous outcomes were included, we were unable to provide a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of models. Third, we excluded cohort studies that reported outcomes but did not involve a comparison group because positive results in studies that report outcomes only for patients receiving treatment might reflect the natural course of illness, or “regression to the mean.” This criterion resulted in the exclusion of several recent cohort studies of robust models that utilized a rigorous implementation approach informed by implementation science frameworks. Studies like these may provide compelling evidence for effectiveness of the model in routine clinical settings (Rimal et al., Reference Rimal, Choudhury, Agrawal, Basnet, Bohara, Citrin, Dhungana, Gauchan, Gupta, Gupta, Halliday, Kadayat, Mahar, Maru, Nguyen, Poudel, Raut, Rawal, Sapkota, Schwarz, Schwarz, Shrestha, Swar, Thapa, Thapa, White and Acharya2021).

In summary, the findings of this rapid review have important clinical implications, as they support the feasibility and effectiveness of Collaborative Care across diverse settings in LMICs. Collaborative Care provides a framework for a team to provide effective population-based, evidence-based, and measurement-based care for a range of mental disorders. The review also highlights areas where further research is needed. For effective measurement-based care, there is a need for validation and adoption of (preferably self-administered) clinical rating scales that are appropriate for different populations and different levels of the health care system (Ndetei and Jenkins, Reference Ndetei and Jenkins2009; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Fekadu, Jordans, Kigozi, Petersen, Shidhaye, Honikman, Lund, Prince, Raja, Thornicroft, Tomlinson and Patel2016). There is also a need for future studies to evaluate longer-term outcomes and to inform strategies to address implementation challenges. Randomized trial designs are poorly suited to understanding implementation barriers that are specific to a local context. Nonexperimental approaches can be used to rigorously evaluate strategies that emerge from within health systems or communities, and there is a need for more research that is informed by implementation science (McGinty and Eisenberg, Reference McGinty and Eisenberg2022). In addition to lighting the path for future implementation science research about Collaborative Care in LMICs, the findings of this review can also assist health care administrators and policy makers in more effectively designing and implementing Collaborative Care models that meet their populations’ integrated care needs.

Conclusion

This rapid review provides evidence that Collaborative Care is a robust strategy to address the mental health treatment gap for common mental disorders, unhealthy alcohol use and psychosis in LMICs. Despite the more limited resources available in LMICs, effective Collaborative Care models in these settings were based on the same core principles of effective Collaborative Care in HIC settings (team-based care, population approach, evidence-based treatments, and systematic measurement of outcomes over time to inform treatment intensification). Models operationalized these components differently, demonstrating significant innovation in tailoring to local contexts; and there was clear evidence that specific resources and support for implementation is required. These studies suggest that there is no “optimal” Collaborative Care model for all contexts. Instead, implementers and policy makers should seek the best model that is useful for a given setting (Wyrick et al., Reference Wyrick, Rulison, Fearnow-Kenney, Milroy and Collins2014), with careful consideration of affordability, efficiency and potential scalability.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.60.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.60.

Acknowledgement

We thank Diane Powers for insights during development of this project.

Author contributions

T.J. collaborated in the research of rapid review methodology, designing the search strategy and completing the literature search. J.W., S.O., A.B., B.F. and L.C. outlined the objectives and purpose of this review, reviewed the search strategy, collaborated on inclusion and exclusion criteria, reviewed the final study protocol, engaged in title and abstract screening and contributed to revisions of manuscript drafts. J.W., S.O., B.F. and L.C. completed full-text reviews. J.W., S.O. and L.C. collaborated on data extraction and risk of bias assessments. J.W. and L.C. reviewed all excluded studies, reached consensus final studies included, constructed tables and collaborated on drafting the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Dr. Petersen and the Editorial Board and Staff at Global Mental Health,

Thank you for the invitation to submit this manuscript titled "Successful Ingredients of Effective Collaborative Care Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Rapid Review" as a Review Article for potential publication in the Global Mental Health.

This manuscript synthesizes the evidence for Collaborative Care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and distills shared model components of effective programs by offering a rapid review of clinical trials to date regarding the effectiveness and intervention characteristics of Collaborative Care models in treating a range of psychiatric conditions in primary care and outpatient medical settings. Results from this review can help provide increased understanding of successful Collaborative Care models—including specific model components— that is vital for policy makers and healthcare systems which seek to implement Collaborative Care in LMICs.

All authors have contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript. None of the authors have competing interests related to this manuscript. All authors have given approval for the submission of this manuscript. This manuscript is not being considered for publication elsewhere. Results included in this manuscript have not been previously presented. This study was not funded by any sources or organizations.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jessica Whitfield

Dr. Lydia Chwastiak

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, WA, USA