In 2015, the census projected that by 2044, the United States would be a majority-minority country, where “people of color” will achieve numerical majority status (Colby and Ortman Reference Colby and Ortman2015). Scholarship has recently taken a turn toward a more thorough understanding of the broader identity terms “people of color” (PoC) and “women of color” (WoC). The mainstream definitions are that both encompass nonwhite persons and women, respectively, across race and ethnicity. Efrén Pérez and colleagues have advanced our understanding of PoCs, including finding that the most prototypical racial group is perceived to be Black Americans and identifying the varying power differentials across groups of color (Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022; Pérez, Robertson, and Vicuña Reference Pérez, Robertson and Vicuña2023; also see Starr Reference Starr2022; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2023). This literature on PoC identity, however, does not include a gendered lens.

Other scholarship intervenes by examining WoC. Unlike some of the scholarship on PoC that assigns PoC identity to individuals who could be categorized as such, Matos and colleagues (Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2023) make an argument that self-identification as a WoC matters socially and politically. Furthermore, while the likelihood of identifying as WoC depends on being Black, Latina, or Asian American, as does the level of linked fate with other WoC (Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022a), research suggests that the politics of WoC are wide-ranging and historically grounded (Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022b; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2023). This work finds that to self-identify as a WoC has utility for women voters, for campaigning as a WoC, and for coalition-building across women (Carey and Lizotte Reference Carey and Lizotte2023). Carey and Lizotte (Reference Carey and Lizotte2023) find that higher levels of WoC linked fate have the potential for cross-racial coalitions on policies related to gender and racial justice.

A coalitional identity that is vastly undertheorized is that of “men of color.” Past research has not examined the MoC identity or the implications of MoC linked fate. We seek to understand if men who could be categorized as “men of color” subscribe to an MoC linked fate, examining Black and Latino men. We also make an argument about the political implications of MoC linked fate, linking the expression of a “men of color” linked fate with support for women candidates including those explicitly labeled as “women of color.” We theorize that MoC linked fate signals a broader and more coalitional perspective and will be positively related to support for women of color candidates.

Understanding how Black and Latino men make decisions about women candidates of color is imperative for the advancement of the race, ethnicity, and politics (REP) field. WoC outpace men of color (MoC) in the growth of voter registration, voting rates, and political officeholding (Garcia Bedolla, Tate, and Wong Reference Garcia Bedolla, Tate, Wong, Thomas and Wilcox2005; Hardy-Fanta et al. Reference Hardy-Fanta, Lien, Pinderhughes and Sierra2007; Shah, Scott, and Gonzalez Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2019). A record number of Black (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2021) and Latina (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2022) women ran for and won congressional offices in 2020. Further, women of color, and in particular Black women, remain reliable voters for progressive and Democratic candidates. Black women voters are also the most consistent supporters of Black women (Gershon and Monforti Reference Gershon and Monforti2021; Mosier, Pietri, and Johnson Reference Mosier, Pietri and Johnson2022; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007). Hence, electing Black women and Latinas, and WoC more generally, has significant implications for democracy. WoC elected officials support policies that benefit marginalized and economically disadvantaged communities (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Brown Reference Brown2014; Brown and Gershon Reference Brown and Gershon2016b). Although research about who supports women candidates from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups has expanded (Bejarano and Smooth Reference Bejarano and Smooth2022; Brown, Clark, and Mahoney Reference Brown, Clark and Mahoney2022; Brown and Gershon Reference Brown and Gershon2016a, Reference Brown and Gershon2016b; Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022b; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021; Simien Reference Simien2022), we still know very little about how MoC, and in particular Black and Latino men, view WoC, Black, and Latina women candidates.

Using the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Survey (CMPS), we draw on theories of group consciousness, intergroup relations, and coalition-building to investigate how Black and Latino men evaluate Black women, Latinas, and WoC congressional candidates using feeling thermometers and a survey question gauging the importance of candidates being WoC.Footnote 1 We primarily focus on men’s attitudes toward women candidates to probe the coalitional possibilities that an “of color” identity may yield with a gender out-group, extending racial/ethnic politics research which has primarily investigated voter support for men candidates (Adida, Davenport, and Mcclendon Reference Adida, Davenport and McClendon2016; Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; C. Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Tesler and Sears Reference Tesler and Sears2010). Although WoC may be a racial/ethnic in-group for MoC—depending on how WoC are perceived racially—they are a gender out-group; as such, WoC candidates may not be perceived as the ideal political representatives.

We find that Black and Latino men subscribe to a “men of color” linked fate, with Black men expressing higher levels of MoC linked fate compared with Latino men. We find that MoC linked fate has implications for electoral politics: examining men’s support for women candidates, we find that MoC linked fate is associated with warmer feeling thermometer ratings for Black women and Latina congressional candidates, as well as candidates labeled “women of color.” We also find that MoC linked fate increases Latino men’s interest in candidates being WoC, although the effect is reversed for Black men. We conclude that men’s views on women candidates of color can be enhanced when men take up the gendered “of color” identity of MoC. However, there may be limits to racial/ethnic solidarity across gender lines to the extent that descriptive representation is zero-sum.

Linked Fate as “Men of Color”

A significant theoretical development in the REP field is the emergence of theories and empirical investigations of PoC, or people of color, identity (Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Pérez, Robertson, and Vicuña Reference Pérez, Robertson and Vicuña2023; Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022; also see Starr Reference Starr2022; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2023). Despite common usage of the term PoC in the media, researchers have only recently begun to discern the degree to which individuals who can be categorized as such take up the PoC label. Such studies demonstrate the relevance that “of color” identities hold for many Americans, the variation in who subscribes to a PoC identity, and the downstream effects of these identities. Similar research studies have been undertaken on the contours of the WoC label including self-identity and the link between WoC voters and WoC candidates (Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022b; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021, Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2023).

A gender lens is often applied to women as political subjects, with scholars commonly equating the category of “gender” with “women.” But gender as a category and source of identity encompasses men including men of color. What an “of color” identity might entail for men as a gender group has yet to be examined. We contribute to this debate through an exploration of “men of color” linked fate. Linked fate, which is the belief that one’s life outcomes are interconnected with that of other group members (Dawson Reference Dawson1994), has not been considered from the vantage point of “men of color” as a group. What it means to be a person of color might vary with gender identification, making for stronger in-group bonds with individuals who share one’s gender as well as race/ethnicity.

The measure of linked fate was created to operationalize Black group consciousness (Dawson Reference Dawson1994). Scholars have, however, extended the concept to other racial and ethnic groups as well as other identity categories such as gender, class, and religion (Gay, Hochschild, and White Reference Gay, Hochschild and White2016). Surveys, for example, show that Latinos express a sense of linked fate (Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010),Footnote 2 resulting in the overall understanding that linked fate is not unique to one group but that the concept is intricately tied to the history of Black Americans.

Both Black and Latino men may find common cause with “men of color” per se. As Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) and Starr and Freeland (Reference Starr and Freeland2023) have theorized, being a PoC is more than a demographic term; it is also a source of identity. But the experiences of being PoC may be gendered. After all, how gender identity and gender equality should figure into struggles for racial equality are contested topics (Giddings Reference Giddings1984; Carbado Reference Carbado1999; Roth Reference Roth2004; Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007). Even if racial/ethnic groups gather beneath an “of color” umbrella, the question of whose interests are represented in that coalition remains.

The history of the concept of linked fate, recent linked fate research, and new work on PoC identity lead us to believe that Black men might have higher levels of MoC linked fate than Latino men. Research on the PoC identity (PoC ID) finds that the prototypical “PoC” is Black and that “PoC ID” is higher for Blacks than Latinos (Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2023). Starr and Freeland (Reference Starr and Freeland2023), for example, find that non-Hispanic Black Americans (96%) followed by Black Latinos (93%) self-identify at the highest rates as PoC, whereas only 45% of Latinos of any race self-identify as a PoC. The same trend follows in relation to PoC linked fate, where 77% of non-Hispanic Blacks and 50% of Latinos agree that “what happens generally to people of color” will affect their lives (Reference Starr and Freeland2023, p. 12). Using 2020 CMPS data, Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022a) found that WoC Identity (WoC ID) was highest for Black women (91%) followed by Asian American women (58%) and Latinas (36%). They found that WoC linked fate was highest for Black women followed by Latinas and then Asian American women.

Scholars have also examined Black Americans’ expressions of linked fate by gender (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Simien Reference Simien2005; Tate Reference Tate1993) and have found some differences. In the 2012 American National Election Study (ANES), for example, 68% of Black men, compared with 60% of Black women, expressed Black linked fate, a significant difference among Black Americans. However, there were no gender differences among Latinos’ expressions of Latino linked fate. Simien (Reference Simien2005) finds that Black men expressed linked fate with Black men at higher rates than Black women but that there were no gender differences in Black men and women’s expression of linked fate with Black women. Gershon et al. (Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019) find that Latino males have the lowest levels of minority linked fate compared with Black men, Black women, and Latinas. Given these findings, we hypothesize that

H1: Black men will score higher than Latino men on MoC linked fate.

MoC Linked Fate and Support for WoC Candidates

Theories of intergroup relations have found that superordinate identities can foster intergroup cooperation (Sherif et al. Reference Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood and Sherif1961). For example, in times of crisis, a shared national identity has been a uniting force (Transue Reference Transue2007). Scholarship on PoC also reveals that a PoC identity fosters coalition-building among racial and ethnic minoritized groups (Pérez Reference Pérez2021). Research on WoC captures a similar coalition among self-identified WoC who support women of color candidates at higher rates than do white women (Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021). Linked fate, we argue, plays an important role in how minoritized groups understand and make decisions about political candidates (Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019). In their work, Gershon et al. (Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019) find that “minority linked fate” may be related to perceptions of representation from diverse political candidates, although we should note that their measure did not take into account the potential for gendered aspects of minority linked fate. The authors find that higher levels of minority linked fate were associated with higher levels of perceived representation for all the minority candidates, both in-group and out-group members regardless of gender. Hence, we contend that MoC linked fate, as an expression of group consciousness (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009), will serve as a mechanism through which Black and Latino men can increase their support for Black women, Latina, and women of color candidates. The “of color” grouping can gather women and men in a common cause against a white out-group.

The literature on candidate evaluations often focuses on evaluations of men candidates even when the research question concerns racial and ethnic minoritized groups. Kaufmann (Reference Kaufmann2003), for example, found that the majority of both Black Americans and Latinos supported the Black and Latino candidates in distinct Denver, CO, mayoral races although Black voters supported the Latino candidate at higher rates than Latino voters supported the Black candidate. Even though the work by Schwarz and Coppock (Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022) finds that on average, the effect of being a woman candidate increases support by 1.8 percentage points, they also find that this effect was stronger among white candidates compared with Black candidates and stronger for women respondents compared with men respondents. Hence, evaluations of Black and Latino men, as MoC potential voters, and their support for women and women of color candidates are a continued gap in the literature of candidate evaluations.

The work by Bejarano and team furthers this research by examining co-ethnic and co-gender support for candidates. Bejarano (Reference Bejarano2013), for example, found that broadly ethnoracial minorities supported other ethnoracial minority incumbents over white incumbents. In their 2021 work, Bejarano et al. examine whether shared racial and gender identity is associated with Black and Latina/o voters’ beliefs about how well a candidate of a different race and/or gender will represent them (Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Brown, Gershon and Montoya2021). They find that among Latino respondents, a stronger sense of minority linked fate—measured as linked fate with “racial and ethnic minorities”—is positively associated with an increase in expressing that a Latino man and a Black woman candidate will represent their interests. Among Black men, the authors find that not sharing the ethnoracial and gender identity of the candidate is negatively associated with the likelihood that the candidate will represent their interests.

Other scholarship identifies the ways that gendered interests can divide communities of color (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007; Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014; Capers and Smith Reference Capers, Smith, Brown and Gershon2016; Carbado Reference Carbado1999; Harnois Reference Harnois2017; Hill Collins Reference Hill Collins2004; Robnett and Tate Reference Robnett and Tate2023; Simien Reference Simien2005). Within communities of color, gendered inequalities in power, resources, and status can lead to differences in political agendas and opportunities for coalitions that are gender-specific. Variation in perspectives and policy priorities can create dynamic arrangements of in-groups and out-groups that fall along the lines of race and gender, including cross-racial and panethnic coalitions.

Sigelman and Welch (Reference Sigelman and Welch1984) found that African American men were less likely to vote for a woman presidential candidate compared with African American women. Philpot and Walton (Reference Philpot and Walton2007) found that Black men and women were equally likely to support a Black woman candidate over a white man or woman candidate; however, if a Black woman ran against a Black man, a gender gap emerged. Likewise, Montoya et al. (Reference Montoya, Bejarano, Brown and Gershon2021) using data from the 2016 CMPS find that Black women and men see Black candidates as likely to represent their interests with evidence of gender affinity effects. That Black men’s race identification was found by Simien and Clawson (Reference Simien and Clawson2004) and Simien (Reference Simien2005) to be positively related to gender identification suggests that equality for Black women and Black men can coexist. Indeed, Simien (Reference Simien2004) concludes that “black feminist consciousness is quite widespread among both black women and black men” (330–331). Few gender differences in policy are usually evident among Black voters compared with white voters.

There is considerably less research on Latinos’ support for Latinas in politics. Bejarano (Reference Bejarano2013) found that Latino men were supportive of Latinas, their co-ethnics, in politics. Montoya et al. (Reference Montoya, Bejarano, Brown and Gershon2021) found that Latinos and Latinas see Latino/a candidates as likely to represent their interests with evidence of gender affinity effects. Latino candidates were perceived to be more likely than Black candidates to represent their interests.

We propose that those higher in MoC linked fate may find more commonality with women candidates from racial out-groups, as well as WoC candidates who explicitly share the “of color” label.

H2: We hypothesize that MoC linked fate will be positively related to feeling thermometer ratings for Black women, Latinas, and WoC congressional candidates, for both Black and Latino men.

H3: We hypothesize that MoC linked fate will be positively related to seeing WoC candidates as important, for both Black and Latino men.

Data, Methods, and Descriptive Summary

We turn to the most comprehensive dataset of public opinion and elections for studies of race and ethnicity: the 2020 CMPS (Frasure et al. Reference Frasure, Wong, Barreto and Vargas2021). The study represents the first national data collection of men’s linked fate with “men of color” as well as the first data collection of “WoC” congressional candidate feeling thermometers, offering an unprecedented opportunity to probe the ways that gender and race interact for men’s attitudes and political behavior.

The key dependent variables of interest are the questions that ask respondents to place groups of congressional candidates on a 0–100 feeling thermometer.Footnote 3 To further evaluate views of WoC, we include a measure of the importance the respondents place on a candidate being WoC.Footnote 4 Our main independent variable of interest is the linked fate question concerning “men of color” (“MoC linked fate”) to measure that raced and gendered coalitional identity.Footnote 5 Whereas Gershon et al. (Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019) previously examined minority linked fate, we explicitly test for the gendered dynamics of linked fate.

Following the research of Montoya et al. (Reference Montoya, Bejarano, Brown and Gershon2021), we are interested in the ways that Black men and Latino men assess the different candidate race and gender subgroups. We make a unique contribution by including a feeling thermometer for WoC congressional candidates explicitly labeled as such.

Before turning to the multivariate analyses, we display the feeling thermometer ratings of our sample. While our hypotheses concern the relative evaluations of different groups of women candidates, for the purposes of providing descriptive statistics, we first include evaluations of men congressional candidates.

Table 1 indicates that Black men’s evaluations of Black men congressional candidates and Black women congressional candidates are statistically indistinguishable. Black congressional candidates are rated more highly than Latino congressional candidates. While we expected Latina congressional candidates to be rated lower than Latino congressional candidates, the reverse was true: Black men are warmer toward Latina congressional candidates than Latino congressional candidates.

Table 1. Feeling thermometers: how men of color evaluate congressional candidates

Source: Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (2020).

Cell entries are means on the 101-point feeling thermometer (0–100) with standard deviations in parentheses.

N = 1889 (Black men), 1694 (Latino men).

* Out-group mean is significantly different from race-gender in-group mean.

For Latino men, similarly, the racial/ethnic in-group (Latino) congressional candidates are rated more highly than are Black congressional candidates. Latino men do not differentiate between Black men and Black women congressional candidates. For neither Black men nor Latino men do we find evidence of gender solidarity with the racial/ethnic out-group.

Past scholarship has not measured Black and Latino men’s attitudes toward congressional candidates explicitly labeled “WoC.” While Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) did not assess gender, he found that Black Americans are the prototypical PoC. If this applies to WoC, WoC evaluations may be like evaluations of Black women congressional candidates. On the other hand, to the extent that WoC implies a group beyond Black women, the evaluations of WoC may be lower than evaluations of Black women.

To the degree that Latinos, too, view Black women as the prototypical WoC, they may regard WoC as less of an in-group compared with those described as Latina. At the same time, if WoC is broader than Black women and could encompass Latina women as well, Latino men’s evaluations of WoC could be higher than their evaluations of Black women congressional candidates.

Table 1 sheds light on these relationships. For Black men, WoC congressional candidate evaluations are one point lower than that for Black men and Black women candidates, but the difference is not statistically significant. These findings may suggest that Black men primarily view WoC congressional candidates as Black women. Black men rate WoC candidates higher than Latina candidates, indicating that Black men do not equate the appeal of WoC candidates with one of the groups that could be labeled WoC: Latinas.

The results are similar for Latino men in that WoC and Black candidates are scored similarly and below Latino men and Latina congressional candidates (see Table 1). Latino men’s evaluations of WoC and Black women congressional candidates are not statistically distinguishable. WoC appear to be an out-group on both race/ethnic and gender grounds. Despite the common social categorization of Latinas as WoC, Latino men seem to make a distinction between the two groups of women candidates.

In sum, we see that men of color make distinctions across groups of women congressional candidates even though all could arguably be categorized as “of color” women candidates.

Main Analytic Plan and Results

Our first hypothesis concerned the strength of MoC linked fate for Black men compared with Latino men. We find that Black men score higher on MoC linked fate (mean = 3.2, sd = 1.4) than Latino men (mean = 2.6, sd = 1.2) as we had anticipated. This difference may indicate that Black men are more likely to see themselves as “of color” than are Latino men, consistent with Starr and Freeland (Reference Starr and Freeland2023), who also find that PoC ID is much lower among Latinos. However, MoC linked fate is gendered as well as raced, which may affect men’s solidarity levels.

To better understand the political implications of MoC linked fate and heterogeneity in men’s attitudes, we turn to a multivariate analysis and a linear regression model; linear regression is appropriate given the nature of our dependent variable which varies from 0 to 100. Our main independent variable of interest is MoC linked fate. Because higher MoC linked fate signals an interest in communities of color, including WoC, we expect that higher MoC linked fate will be positively related to all the women candidates’ feeling thermometers.

In the multivariate analysis, we also control for variables related to political engagement (e.g., party identification and political interest) and demographic factors (e.g., age, education, and income). We control for hostile sexism and benevolent sexism, following women and politics researchers (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019; Winter Reference Winter2023). Because the phrase “women of color” is specific to the US context, we control for nativity and whether a language other than English is spoken in the home, following race/ethnic politics and immigration research.Footnote 6

We expect that out-group considerations will also play a role in attitudes toward women candidates. Sanchez (Reference Sanchez2008), for example, finds that Latinos with strong expressions of Latino linked fate are less likely to have negative stereotypes of African Americans. This is consistent with Kaufmann’s (Reference Kaufmann2003) findings that Latinos who feel closer to other Latinos are more likely to perceive commonality with Blacks. Newer scholarship on shared marginalization and PoC solidarity suggests that groups who feel a shared marginalization or discrimination with an out-group will be more likely to have positive attitudes toward the out-group and policy preferences that help the out-group (Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022). Of importance in this work is similarity in experience rather than identity (see Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Brown, Gershon and Montoya2021; Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017).

To control for perceptions of out-group discrimination, we use the question: “How much discrimination, if any, do you think exists against each of the following groups in the United States today?” For Blacks, the out-group measure concerns beliefs about the extent of discrimination faced by Latinos; for Latinos, the out-group measure concerns beliefs about the extent of discrimination faced by Blacks. For Black and Latino men who perceive the out-group experiences racial discrimination, feeling thermometer ratings for candidates from that out-group should increase.

At the same time, scholars examining Black and Latino relations often describe interactions as laden with conflict. Some scholars have found that Latinos see little commonality with African Americans (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2007) and see the relationship as competitive in nature (McClain and Karnig Reference McClain and Karnig1990; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Lyle, Carter, DeFrancesco Soto, Lackey, Cotton, Nunnally, Scotto, Grynaviski and Kendrick2007; Meier and Stewart Reference Meier and Stewart1991). Some work has found that Latinos express stereotypical views of African Americans. McClain and colleagues (Reference McClain, Carter, DeFrancesco Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally, Scotto, Kendrick, Lackey and Cotton2006) find that in North Carolina, Latinos expressed that Black Americans did not work hard and were untrustworthy. These feelings were not necessarily reciprocated by the Black respondents, the majority of whom responded that Latinos were hardworking and trustworthy. Latino men, compared with Latinas, held more negative stereotypes of African Americans. Because of this line of research, which suggests that there may be feelings of threat or competition between the two groups, we control for a geographic version of group threat. We use a question that asks respondents about the relative presence of different racial groups who live within their zip code. To measure group threat from the standpoint of Black respondents, we subtract the percentage of Blacks from the percentage of Latinos; for Latinos, we subtract the percentage of Latinos from the percentage of Blacks. Higher values on this variable indicate more threats from the out-group.Footnote 7

Results

Our expectations about MoC linked fate are largely confirmed in the multivariate analysis (Tables 2 and 3). This is the case for both Black men and Latino men.

Table 2. Determinants of Black men’s evaluations of women candidates

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Source: Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (2020).

Note: “Black women FT” is the feeling thermometer for Black women congressional candidates, “Latina women FT” is the feeling thermometer for Latina women congressional candidates, “WoC FT” is the feeling thermometer for “women of color congressional candidates” (all 0–100), and “WoC importance” is a five-category question about the importance of a candidate being WoC.

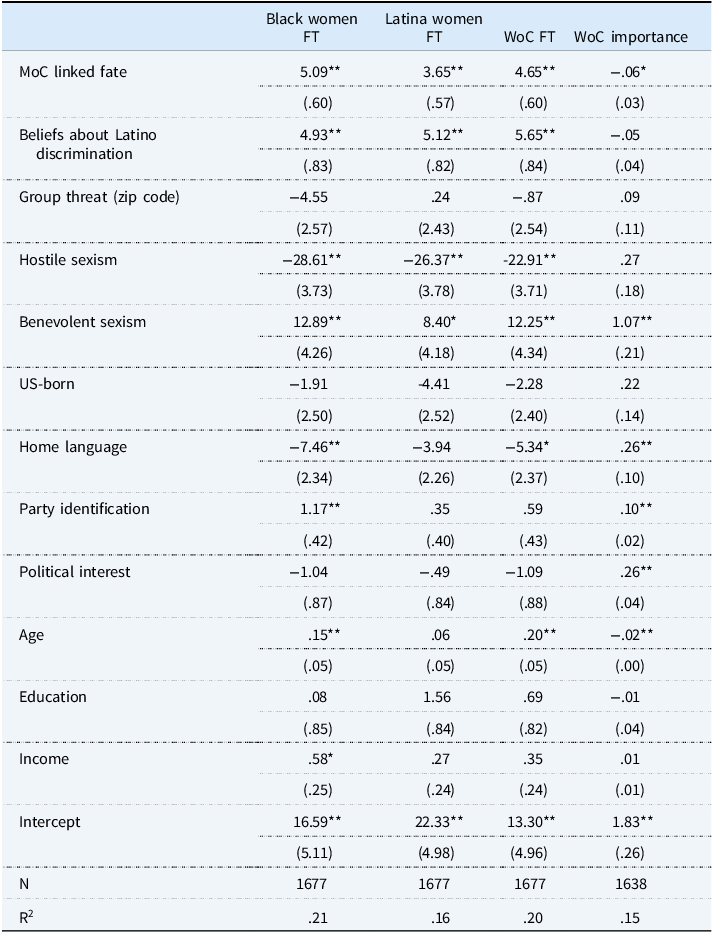

Table 3. Determinants of Latino men’s evaluations of women candidates

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Source: CMPS (2020).

Note: “Black women FT” is the feeling thermometer for Black women congressional candidates, “Latina women FT” is the feeling thermometer for Latina women congressional candidates, “WoC FT” is the feeling thermometer for “women of color congressional candidates” (all 0–100), and “WoC importance” is a five-category question about the importance of a candidate being WoC.

We find that the more that men think that what happens to MoC affects them, the warmer they are toward Black women, Latina, and WoC congressional candidates. These positive relationships suggest that the MoC and WoC labels are ones that transcend a single racial/ethnic group. Depending on the sample and the dependent variable, moving one unit on the 5-point linked fate measure increases scores on the feeling thermometer from 3 to 5 degrees. Although the gender dimension of MoC linked fate might signal distinct raced-gendered interests for men, the results are in a positive direction as we hypothesized. This is also the case for the importance Latino men place on a candidate being WoC: the stronger MoC linked fate, the more interest is evident in candidates being WoC.Footnote 8

However, in contrast to the results for Latino men, we find that higher MoC linked fate reduces the importance that Black men place on a candidate being WoC. This negative relationship may be indicative of perceived trade-offs in whose representation should be a priority: the election of WoC might reduce the election of MoC because there are a finite number of elected positions. This is the only result in our analyses that hints at the limits of racial and coalitional solidarity across women and men. However, given the descriptive findings, it might be that Black men read WoC candidates as indistinguishable from Black woman candidates. If this is the case, it is consistent with some past research about the perceived costs to Black men of Black women’s leadership (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Simien Reference Simien2015). At the same time, this is the only effect that is in the negative direction.

Turning to the control variables, we expected that as men perceive higher levels of discrimination for the racial/ethnic out-group, their thermometer evaluations of Black women/Latina congressional candidates will rise. These expectations were borne out in the results displayed in Tables 2 and 3. Black men who perceive that Latinos as a group experience higher levels of discrimination are more likely to rate Latina congressional candidates higher. They were also warmer toward Black women congressional candidates and WoC congressional candidates. In line with prior work (Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Brown, Gershon and Montoya2021; Cortland et al. Reference Cortland, Craig, Shapiro, Richeson, Neel and Goldstein2017; Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Pérez, Vicuña, and Ramos Reference Pérez, Vicuña and Ramos2023; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017), these findings suggest that awareness of racial/ethnic discrimination generally leads to higher scores for underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Perceptions of the discrimination facing Black people as a group likewise were positively related to Latino men’s evaluations of Black women congressional candidates (see Table 3). The effect is positive for the other groups of women candidates as well, like the relationships we observe for Black men.Footnote 9

We did not find a statistically significant effect of perceptions of discrimination for Black men or Latinos on the fourth dependent variable in our tables, which is the importance respondents place on a candidate being WoC (see Tables 2 and 3). Beliefs about racial/ethnic discrimination faced by the out-group did not influence the value placed on a candidate being WoC. Unlike the thermometer questions that gauge warm (or cold) feelings toward candidates, the important question is about voters’ priorities. That discrimination perceptions do not drive beliefs may reflect ambiguity about the meaning of the WoC label or lack of solidarity with the goal of electing more WoC.

We hypothesized that group threat, measured with the relative balance of Blacks and Latinos in the respondent’s zip code, would reduce Black men’s evaluations of Latina candidates and Latino men’s evaluations of Black women candidates.Footnote 10 However, we did not find an effect on the thermometers. We did find that group threat is positively related to Latino men’s assessments of how important it is that a candidate is WoC. This finding may indicate that familiarity with the out-group leads to more support for WoC candidates. At the same time, if Latino men perceive WoC to include Latinas, then group threat may lead Latinos to want to elect more individuals from their in-group: WoC. Because the CMPS does not have a direct measure of who Latinos (or Black men) perceive to be WoC, we can only speculate at this point about the meaning of this result. Meanwhile, the threat measure does not have an effect for Black men.

Discussion

We first found that Black men feel warmer toward Black congressional candidates followed by Latinas. Latino men feel warmer toward Latina/o congressional candidates and do not differentiate between Black men and women congressional candidates. Both Black men and Latino men evaluate WoC and Black candidates similarly. Black men rate WoC candidates higher than Latina candidates, while Latino men rate Latina congressional candidates higher than WoC candidates. These thermometers are important in that they ask about raced-gendered congressional candidates not just racial/ethnic candidates. Similar to findings by Simien (Reference Simien2005), although Black men rated Black men congressional candidates slightly higher than Black women, the differences are not significant, and Black men’s racial consciousness as it relates to support for Black congressional candidates seems to outweigh their gendered identity. Although Black men and Black women experience race differently due to their gender, it seems that for Black men affect toward Black women and WoC candidates are not reduced because of disparate gendered experiences. The same is the case for Latinos, whose feelings for Latino candidates are higher than for Latinas but not statistically different. These findings are in line with Bejarano’s (Reference Bejarano2013) work on Latino men’s support for Latinas (also see Montoya et al. Reference Montoya, Bejarano, Brown and Gershon2021).

We also found that Black men are more likely to express linked fate with “men of color” compared with Latino men. These findings seem to indicate that Black men see themselves represented in the “of color” term more so than Latino men. An exploration of social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986) illuminates this particular finding. The “of color” part of the terminology, like that of PoC (Pérez Reference Pérez2021) and WoC, might be read as Black among Black men. SIT posits that group members often want to be part of a distinct and positive group. To the extent that Latino men do not want to share an “of color” identity with Black men, they may not express linked fate with “men of color.” Furthermore, to the extent that Latino men are also anti-Black, they are less likely to express linked fate with “men of color,” if they see the “of color” as being primarily Black (Pérez, Robertson, and Vicuña Reference Pérez, Robertson and Vicuña2023). Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Vicuña and Ramos2023) manipulate Latinos’ feelings of Americanness, and when they prime Latinos to feel less American, Latinos become more anti-Black. Thus, to the extent that Latinos want to bolster their own distinct group, their anti-Black sentiments might increase leading them to disidentify with a MoC identification and dampen linked fate.

Linked fate as a concept is important for cross-racial and cross-gender solidarity and coalition-building (Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Brown, Gershon and Montoya2021; Carey and Lizotte Reference Carey and Lizotte2023; Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019). The extension of linked fate beyond African Americans, as it was originally intended (Dawson Reference Dawson1994), has been contested (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009). McClain et al. (Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009), for example, argue that the concept of linked fate has been overextrapolated. However, other works argue that linked fate excludes cross-cutting issues such as around gender and gender identity (Cohen Reference Cohen1999). In this paper, one could critique our use of linked fate as it concerns Latino men and the MoC group.Footnote 11 The notion of group consciousness is grounded in feelings of groupness based on systemic inequality. Research has shown that Latinos in the aggregate experience discrimination and believe that Latinos as a group experience discrimination, which subsequently grounds group consciousness among Latinos. In fact, discrimination is one of the factors that influence higher levels of Latino group consciousness (Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010; Sanchez, Masuoka, and Abrams Reference Sanchez, Masuoka and Abrams2019).

Our paper shows that MoC linked fate matters as it relates to men’s attitudes toward the importance of WoC candidates. The more that Black and Latino men think that what happens to MoC affects them, the warmer they are to Black women, Latina, and WoC congressional candidates. MoC linked fate, then, transcends a single racial/ethnic group. Furthermore, the stronger MoC linked fate among Latinos, the higher the importance Latinos place on a candidate being a WoC. The shared “of color” experience among Latinos may supersede any gender differences. Future research might delve deeper into MoC linked fate by comparing Black men’s linked fate with their racial group and utilizing the original linked fate questions with a linked fate question specifically about Black men’s linked fate. In Simien’s (Reference Simien2005) work, a higher percentage of Black men indicated more linked fate toward Black men compared with Black women, which might be indicative that for Black men, group consciousness that takes into account both race and gender might be at work.

Meanwhile, we find that for Black men, MoC linked fate reduces the importance they place on a candidate being a WoC. Black men may be thinking about the perceived zero-sum game of descriptive representation because they see the prototypical WoC congressional candidates as Black woman candidates. In line with scholarship about gender dynamics within the Black community (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Simien Reference Simien2015), Black men might perceive electing WoC, who they see as Black women, as at odds with Black men’s leadership. Philpot and Walton (Reference Philpot and Walton2007) also found that although Black men matched Black women’s support for Black women candidates, this was only if her opponent was not a Black man candidate. In other words, when a Black woman candidate’s opponent was a Black man, Black men showed less support for the Black woman. However, we caution that this result was the sole negative effect we found for the MoC linked fate variable.

MoC linked fate might also have implications for the literature on representation. Prior work has found that minority linked fate is linked to how well minoritized individuals think out-group members by race and/or gender represent their interests. In this work, Black men’s perceptions of the WoC category seem to be indistinguishable from Black women at the expense of seeing the importance of candidates being WoC. This is distinct from Latinos who might perceive WoC candidates as broader. Future work might consider whether MoC linked fate similarly influences representation. As the country becomes more majority-minority, linked fate across race/ethnicity and gender might become imperative for groups that remain underrepresented in local, state, and national elected positions. The exploratory nature of this work contributes to a larger understanding of Black and Latino men’s voting behavior. Indeed, it is possible that, to the extent that MoC perceive gender differences in racialized experiences (Lindsay Reference Lindsay2015), Black and Latino men may be more or less supportive of WoC in political leadership roles. Candidates’ platforms and the salience of particular agenda items might play a role as well.

Conclusion

We join other scholars in interrogating the political significance of “of color” categorizations. By establishing that Black men are higher in MoC linked fate than Latino men, we contribute to debates about which “of color” identities hold appeal for voters. Regardless of these average values, the MoC linked fate item held explanatory power for both groups of men. The scores of men on the MoC linked fate measure and the association of this measure with candidate support indicate that “of color” identities are both racialized and gendered.

Unlike past work, we probed both race/ethnicity and gender to understand men’s support for candidates who could be considered within their coalition: women candidates “of color.” By measuring MoC linked fate and attitudes toward WoC candidates, explicitly labeled, we offer novel, exploratory evidence of how men conceptualize “MoC” and “WoC” and the boundaries of those groups. Most of our evidence pointed to a positive relationship between MoC linked fate and support for women candidates, suggesting that WoC are perceived as an in-group.

The views of MoC toward WoC depend on race, gender, and coalitions. While we do not have direct measures of men’s identity as “MoC” or which groups men see as “WoC,” our results are suggestive. Black men and Latino men differ in how they perceive themselves on raced-gendered lines as well as how they perceive the contours of the women candidates who might represent them. Because of the correspondence between views of “Black women” and “WoC” candidates, it may be that Black women are perceived to be the prototypical WoC candidates. And yet other evidence hints that WoC resonate with men in a way that can lead to broader coalitions beyond one’s racial in-group. More work should be conducted to decipher whether these findings are because of the ambiguity of the term WoC or if there is a solidarity threshold for Black and Latino men if there is a zero-sum outcome. Our research design did not address the possibility that supporting women candidates could lead to the displacement of men incumbents or lower odds for men candidates; future research can take up how MoC linked fate impacts these dynamic relationships.

Future research can take up these questions further to better understand how men who are Asian American, Middle Eastern/North African, and Native American, as well as Black Latinos, navigate their race and gender identities and those of other candidates. One practical appeal of “of color” identities is the broader coalition and sizable voting bloc that can emerge. Yet, coalitions may be unlikely due to factors such as unique group experiences and negative out-group evaluations, and coalitions bring the risk of erasure (Edwards and McKinney Reference Edwards and McKinney2020). To the degree that the public, the media, and candidates themselves invoke these identities in the future, researchers will want to unpack the meaning and consequences of PoC—for men and women. Future studies could also consider how attitudes toward WoC candidates in the abstract are brought to bear on voting decisions for particular individual women candidates.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2024.10.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and reviewers for their thoughtful engagement, comments, and feedback throughout the process.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

None.