With increasing awareness of the pervasiveness of child-hood sexual abuse and the psychological consequences for the child, which can extend into adult life (Reference Bagley and RamseyBagley & Ramsey, 1986; Reference Mullen, Martin and AndersonMullen et al, 1993), child health professionals have looked to provide the most appropriate assessment and treatment for such children. Child sexual abuse can be defined as ‘the involvement of dependent, developmentally immature children and adolescents in sexual activities that they do not fully comprehend and to which they are unable to give informed consent and that violate the social taboos of family roles’ (Reference Goodman and ScottGoodman & Scott, 1997).

Estimates for the prevalence of child sexual abuse range from 5-30% of the population depending on the sample, interview and definition. Studies have shown that 46-66% of children who have experienced sexual abuse can demonstrate significant symptoms (Finklehor & Browne, 1986) affecting their development, emotions, behaviour and cognitions (Reference JonesJones, 1996; Reference Cahill, Kaminer and JohnsonCahill et al, 1999), which can be persistent (Reference Tebbitt, Swanston and OatesTebbitt et al, 1997).

Providing effective and sensitive treatment has been a challenge to the various agencies that are involved with these traumatised families and there are few studies evaluating such interventions. Stevenson (Reference Stevenson1999) under-took an extensive literature review in this area and found very few well-conducted and adequately controlled trials. However, he found that, on the evidence available, psychological treatments can be helpful in improving the mental health of abused children.

There have been very few studies addressing the perceptions of the abused child undergoing therapeutic treatment. In particular, it is not clear how they think they would benefit from attending such services and what aspects of the treatment they would find useful. Prior et al (Reference Prior, Linch and Glaser1999) looked at the views of children and their carers on the social work response to the child's sexual abuse. Essential aspects of social work considered to be important were: providing emotional support and reassurance, listening, providing information and coordinating different services. Their study highlighted the importance of listening to children's views on the therapy and service offered.

The study

The specialist child and adolescent mental health service serving the population of Bridgend, South Wales, provides a multi-disciplinary post-abuse service to which children can be referred for assessment and ‘therapy’ depending on the needs identified. Bridgend is a unitary authority and covers a population of 135 000.

A questionnaire survey conducted at the assessment interview to collect data on the referred child's perceptions of their difficulties and what they both wanted and did not want from attending the service. The issues identified by the referrer as important were recorded from the initial referral letter to the service. The study was conducted over 1 year, from January 1999 to January 2000. The study included all girls who had been referred to the child and family service because they had been sexually abused.

Findings

The questionnaire was completed by 25 children, comprising 96% of those who attended during the study period. Their ages ranged from 6-17 years and they were referred from a variety of sources including the general practitioner, social services, the police and education authority. The majority lived at home with their parent(s). The children were at various stages of the legal process, although for 30% the abuse had not been investigated by the police. The time from disclosure to referral varied from less than 1 month (five cases) to over 2 years (seven cases).

Four children (16%) had received previous therapy. Predominantly the abuse was intra-familial, with the stepfather being the main perpetrator. When the abuse was identified as being extra-familial, a neighbour or family friend was the main perpetrator. In 60% of the sample there was a family history of abuse. Thirteen of the children (52%) were identified as having learning difficulties and 19 (76%) came from a family where the parents had separated.

Specific interventions were requested only by 24% of the referrers and in 76% of the referrals it was unclear what was being asked from the service. Where the referrer was specific, the areas identified included self-protection, parenting, challenging behaviour, anger management, counselling and help with self-harm, sexualised behaviour, nightmares and bedwetting.

The study highlighted differences in problems as perceived by the child and the referrer. Both parties attributed a different degree of importance to each issue identified. In particular, the children were more concerned than the referrer about internalising symptoms that they were experiencing. Children were also anxious that they would not be believed and that they would be blamed for the abuse occurring. They felt humiliated and guilty and were frightened of both the perpetrator and others finding out what had happened to them. Over half of the children felt their confidence and self-esteem were affected but only one of the referrers had highlighted this. Those referring children to the service felt the important issues centred around relationships with peers and the child self-harming. Both parties thought that relationships and communication within the family were major problem areas.

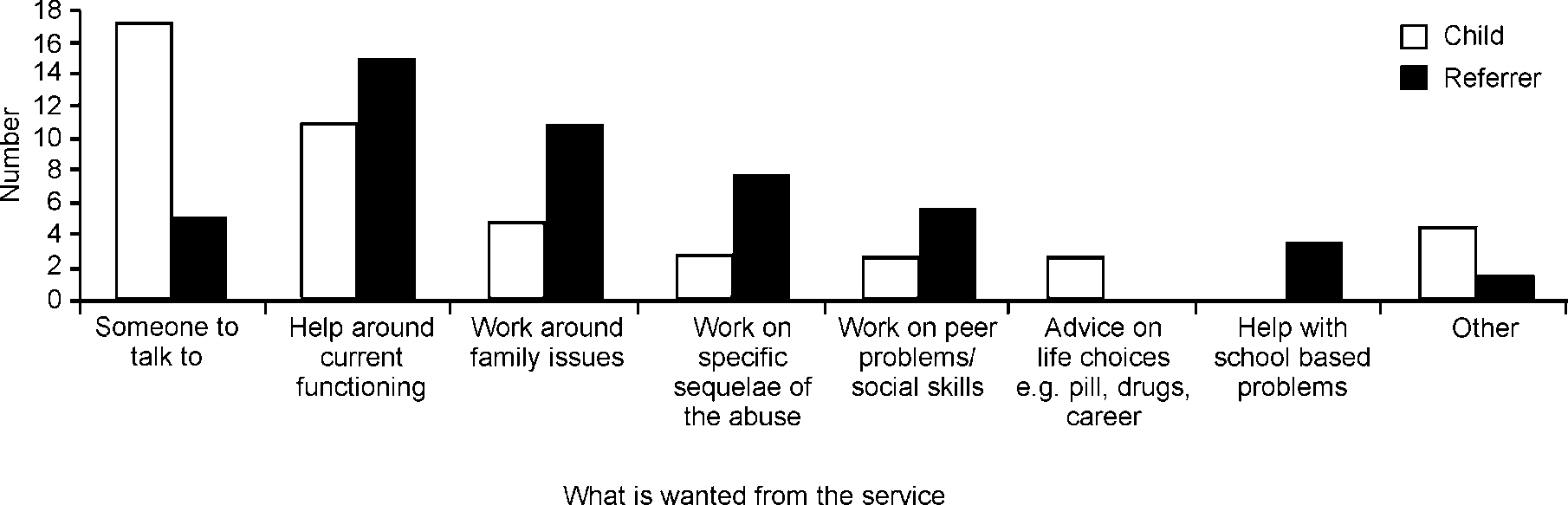

Differences were also identified between what the child wanted from the service and what the referrer requested (Fig. 1). Predominantly, the children wanted someone to talk to about the effect of the trauma on their lives, whereas the referrer asked for more practical and specific help with various problems, in particular with current functioning and family-based issues. Children were also clear about what they did not want from attending the service. They did not want to talk about the details of the abuse, become distressed in the session or be blamed in any way for what had happened. The number of children who wanted to be seen alone and with their family/carer were similar. Just 3 out of the 25 wanted help through group work and no child wanted to only receive therapy by being part of a group.

Fig. 1 What the child wants from the service and what the referrer requests

Discussion

The post-abuse service was an initiative set up by the re-organisation of existing services and no new funding was available. It was established because of a growing realisation of the unmet needs of these children locally, the frustration of referrers, particularly social services, at our service's response, as well as a poor attendance rate following referral. The key elements of the service involve proactive liaison and education of other professionals, a rapid response and attention to the children's and families' perceived needs rather than just assuming what an ‘abused child’ requires. After very considerable initial scepticism, the service has become well-regarded by other professionals and appreciated by the children and their families. This is reflected by an attendance rate of 96%.

The study highlights the importance of attending to what the child wants from a particular service and being aware that, in many cases, what the referrer requests may not match what the child wants. This has enormous implications for engagement and any therapeutic work that is undertaken. Children can be very clear about their needs and if not addressed this may lead to further feelings of rejection and powerlessness. Tackling such issues has helped the post-abuse team to focus its work and to monitor progress. It has also been useful to emphasise to referrers the need to consider why they are referring to the service. In some cases they may have the necessary skills and it may be more appropriate for them to help the child. Other studies have stressed the importance of addressing user satisfaction and the need to seek the views of referred children in providing a therapy (Reference Wigglesworth, Agnew and CampbellWigglesworth et al, 1996). Key aspects identified by this study have been also highlighted as a priority in others, in particular the emphasis on being listened to and accepted (Reference Prior, Linch and GlaserPrior et al, 1999).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.