Introduction

Turkey's political and cultural scene has transformed with the expansion of state-sponsored and minoritarian memory narratives and an active agenda of coming to terms with the past in the last twenty years.Footnote 2 While the Justice and Development Party (AKP; Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) governments have promoted neo-Ottomanism as an ideology and a new historiographical reconfiguration, with alleged claims of imperial tolerance and multiculturalism, the Armenian memory gained significant visibility not only in politics and international scholarship but also in the cultural and public sphere.Footnote 3 At the intersection of clashing imaginaries regarding the Ottoman Empire, independent and subsidized theatres played a key role in giving voice to the hitherto neglected histories of Armenians, albeit in substantially different ways. Unlike independent theatre productions that engage deeply with politically sensitive issues,Footnote 4 public and state theatre productions in this regard tend to focus on the neglected status of Armenians in Ottoman theatre history.Footnote 5 Staging revisionist theatre historiography thus obtains renewed political significance in the context of the Armenian memory boom. The existing scholarship, however, focuses almost exclusively on resistance narratives and historical-justice efforts in independent theatres.Footnote 6 The Armenian memory narratives in Turkish public theatres thus have not received the scholarly attention they deserve. Among these plays, İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Şehir Tiyatroları's (İBBŞT, the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality City Theatres) production of the Ottoman Armenian playwright Hagop Baronian's Adamnapuyj aravelyan (1868) as Şark Dişçisi (The Oriental Dentist) (2011) stands out as a complex case study.

Hagop Baronian's Adamnapuyj aravelyan is a comedy of intrigue about the unfaithful relationship between a so-called dentist and his elderly wife, along with a critique of false westernization. In addition to being one of the first examples of European-style comedy in Western Armenian dramatic literature, Adamnapuyj aravelyan takes its significance from its meticulous depiction of nineteenth-century Ottoman Armenian cultural, social and political life. This play, as well as Baronian's other works, were not translated into Turkish until the 2010s; hence, when İBBŞT included Şark Dişçisi in their repertoire, they engaged with a text that Turkish-speaking audiences have mostly forgotten.

Şark Dişçisi differs fundamentally from Adamnapuyj aravelyan in terms of its play-within-a-play technique and grotesque style in costume and set design. The production stages the story of a fictional Armenian theatre company that performs Baronian's play, utilizing metatheatricality to embrace the forgotten memories of Ottoman Armenian theatre-makers. Although İBBŞT did not categorize the production as an adaptation, Şark Dişçisi displays the main characteristics of adaptation with its additions to and eliminations from its source text.

Adaptation is a process of revision, restoration and interpretation, as well as elimination and erasure. Linda Hutcheon proposes a comprehensive approach to this term: ‘Adaptation is repetition, but repetition without replication. And there are manifestly many different possible intentions behind the act of adaptation: the urge to consume and erase the memory of the adapted text or to call it into question is as likely as the desire to pay tribute by copying’.Footnote 7 Şark Dişçisi illuminates how adaptation operates in numerous ways, comprising seemingly contradictory yet equally essential acts of erasure and paying tribute. In this regard, abjection – the process of becoming ‘separated from another body in order to be’ – provides new perspectives for adaptation's state of being almost but not quite.Footnote 8

Theatre transforms, reformulates, challenges and subverts established narratives as ‘a memory machine’.Footnote 9 As in everyday performance, theatre operates through continuous re-enactment without holding the quality of representing something for the first time. ‘Ghosting’, or ‘haunting’, is thus a key term to discuss the relationship between theatre and memory.Footnote 10 Adaptation also transposes the memory of a former text to another as a medium for and of memory.Footnote 11 Adaptation builds on the pleasure that ‘comes through repetition with a difference and in haunting’.Footnote 12 This pleasure, however, is surrounded by the political and ethical commitments of the adapters.Footnote 13

In what follows, I analyse how Turkey's most established public theatre company, İBBŞT, performs theatre historiography in response to the growing interest in Armenian history. My goal is to uncover the mutual relationship between a so-called forgotten text and its contemporary reinterpretation. Accordingly, I first explore the life and afterlife of Hagop Baronian. Tracing why mainstream theatres in Turkey did not stage Baronian's works for over a hundred years, I examine the process of revision, addition and elimination in Şark Dişçisi, as well as the production's website, ephemera, newspaper articles and interviews, by approaching adaptation as abjection. While promoting confrontation with the past – most notably the history of İBBŞT as a public theatre institution that has a share in the oppression of Armenians – Şark Dişçisi eliminates the crucial political insights of its source text and their ramifications for contemporary demands for historical justice regarding the 1915 Armenian Genocide. The intersection of revisionist theatre historiography and broader political dynamics embedded in the adaptation process reveals the ambivalences of post-Genocide memory work in Turkey.

Hagop Baronian in the time of the Armenian memory boom

The history of European-style theatre in the Ottoman Empire dates back to the first drama staged at the French embassy in Constantinople in 1665.Footnote 14 The construction of the first theatre buildings in the eighteenth century and performances by European troupes, first in embassies and later in newly constructed theatre buildings, paved the way for the formation of local European-style theatre companies.Footnote 15 Multilingual theatrical activities flourished during the modernization, or rather ‘westernization’, movement, highly associated with the Tanzimat (Reorganization) period (1839–76). Ottoman Armenians became the first minoritarian group to perform European-style drama in schools around the 1810s and established professional theatre companies in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 16 They translated and adapted dramatic works from other languages, wrote and performed plays in both Turkish and Armenian – including the first Turkish plays written in the Armenian alphabet or simply in Armeno-Turkish – and trained the first generation of Turkish theatre-makers.Footnote 17

Through the end of the nineteenth century, European orientalists pioneered Ottoman theatre and performance historiography with a focus on folklore.Footnote 18 Drawing from the orientalists' approach to Turkology and the Turkish history thesis,Footnote 19 theatre historians imagined an ethnic link between the prehistoric communities of Anatolia and Central Asia and the contemporary Turkish nation state, with a central question of Turkish theatre's genesis during the formative years of the Turkish Republic (1923–38).Footnote 20 After the 1950s, scholars such as Refik Ahmet Sevengil, Selim Nüzhet Gerçek, Niyazi Akı and Metin And published key reference volumes that range from Central Asian and Anatolian folklore to European-style theatre in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Methodological nationalism characterized twentieth-century theatre historiography, retroactively approaching Ottoman theatre as ‘Turkish theatre activities inside the borders of contemporary Turkey’.Footnote 21

The lack of language competency of the scholars and the broader political pressures on Armenian studies in Turkey brought about the marginalization of Armenians in Ottoman and Turkish theatre histories until the 2000s.Footnote 22 For example, Metin And briefly mentions the first Armeno-Turkish dramas that were written around the 1790s; however, he contends that Şinasi's Şair Evlenmesi (A Poet's Marriage) (1859) should be considered the first Turkish drama because the preceding examples ‘do not belong to the Turkish people’.Footnote 23 And stands out as one of the exceptional theatre historians who engaged with Armenian sources – though without knowing Armenian. He also published a monograph on the pioneer Ottoman Armenian theatre-maker Hagop Vartovyan. As Fırat Güllü discusses, And emphasized how Vartovyan ‘felt Turkish’ and contributed to the formation of a ‘national’ theatre of Turkey, justifying his interest in an Armenian theatre-maker.Footnote 24 Moreover, he included a chapter titled ‘Armenians and the Armenian Question’ in this monograph, where he underlined the political problems of studying Armenians as they are associated with ‘terrorist’ activities as well as theatre.Footnote 25 The tendency to formulate a coherent Turkish national theatre in twentieth-century theatre historiography thus illuminates why Baronian's plays were not translated until the 2010s.

Born in 1843 in Edirne, Hagop Baronian spent most of his life in Constantinople, where he became an outstanding literary figure known for his sharp-tongued style.Footnote 26 At the start of his career, Baronian published Yergu derov dzarav mı (A Servant of Two Masters), an adaptation of Carlo Goldoni's famous play, in 1865.Footnote 27 His second play, Adamnapuyj aravelyan, covers the social and political changes in the context of the nineteenth-century Armenian constitutional movement that culminated in the ratification of the Armenian National Constitution.Footnote 28

After his first attempts at playwriting, Baronian focused on publishing his satirical pieces in several periodicals that he edited. His most famous comedy, Bağdasar ağpar (Uncle Balthazar), was published in one of these periodicals. Apart from his incomplete play Shoghokorte (The Flatterer), this play was Baronian's last comedy. Similar to Adamnapuyj aravelyan, Baronian reflected on marriage and moral corruption entailed by false westernization in Bağdasar ağpar and his 1880 novel Medzabadiw muratsganner (Honorable Beggars).Footnote 29 Baronian also had several prosaic collections, such as Bdoyd me Bolsoy tagherun mech (A Stroll through the Quarters of Constantinople), Kaghakavarutean vnasnere (The Perils of Politeness) and Azkayin chocher (The Bigwigs of the Nation). He contributed to the Armenian cultural renaissance with his works while serving as a member of the Armenian National General Assembly from 1881 until he died in 1891.Footnote 30

Although Baronian actively participated in theatre debates through his periodicals, such as Tadron (Theatre), he never had the chance to see his plays onstage.Footnote 31 Nevertheless, some of the Armenian theatre companies from Constantinople produced Baronian's plays in Baku in the late 1890s.Footnote 32 Baronian's works became part of the Armenian dramatic canon posthumously, while his legacy remained limited in his birthplace. Accordingly, Şark Dişçisi portrays Hagop Baronian as a forgotten literary figure, as can be seen from the play's booklet: ‘Şark Dişçisi is being staged in its full text for the first time in Turkish, 120 years after the death of the Istanbulite Armenian Hagop Baronian, whose name was given to a theatre in Armenia’.Footnote 33 In addition, the play introduces Baronian by mentioning how contemporary Istanbulites do not remember him since even his grave, which is believed to be in Istanbul, has been lost. The production thus underlines the collective amnesia regarding the Armenian cultural heritage; however, the afterlife of Baronian in Turkey is far more complex than a complete loss.

During the First World War (1914–18), the Ottoman Armenian community faced the most horrendous conditions, including the Armenian Genocide. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, Armenian theatrical activities once again flourished for a short period in Constantinople, which was occupied by British, French, Italian and Greek forces.Footnote 34 The triumph of the Turkish War of Independence (1923) resulted in the mass migration of a great number of remaining Armenians, hence the loss of the central position of the Armenian community in Turkey's theatre scene. Although the Turkish government banned staging plays in Armenian from 1923 to 1945, some Armenian theatre companies continued their activities in Turkish. For example, Stüdyo Taderkhump (Studio Theatre) staged Bağdasar ağpar in this period.Footnote 35 After the annulment of the ban, Armenian theatre companies staged canonical works of Armenian drama, including Baronian's plays.Footnote 36 Unfortunately, professional Armenian theatre companies stopped their activities due to the decreasing population of their community, and thereby in their audiences, after the 1960s. Still, Armenian amateur community theatres have produced plays in both Turkish and Armenian.Footnote 37

The Armenian memory boom flourished in and beyond Turkey, especially after the 2000s, and several important developments fuelled this movement. The foundation of Aras in 1993, a publishing house specializing in Armenian history and literature, and Agos in 1996, a newspaper founded by the famous journalist and human rights activist Hrant Dink, became milestones in this regard.Footnote 38 The formation of the Workshop in Armenian-Turkish Studies at the University of Michigan in 2000 influenced the organization of the ‘Ottoman Armenians during the Era of Ottoman Decline' conference, at Istanbul Bilgi University in 2005, which is considered the first step towards breaking the taboo around the Armenian Genocide.Footnote 39 These activities intersected with Turkey's attempts to finalize the accession negotiations with the European Union, which brought other initiatives to establish a diplomatic relationship between Turkey and Armenia.Footnote 40

On 19 January 2007, the assassination of Hrant Dink by the Turkish ultranationalist Ogün Samast fundamentally affected the memory boom. At Dink's funeral, thousands protested hate crimes in Turkey with the seminal slogan, ‘We are all Hrant, we are all Armenians’. While the rigorous translations of Armenian literature and international scholarship after the 1990s contributed to the introduction of Armenian and Armeno-Turkish literature as a new field of research,Footnote 41 ‘the Armenian studies turn’ appeared more urgent than ever after the loss of Dink and escalated towards the centenary of the Armenian Genocide.Footnote 42 In this context, the mainly ignored cultural heritage of Armenians emerged as a politically significant subject.

The first example of Baronian's revitalization in Turkey is the 2006 production Bağdasar Kardeş (Uncle Balthazar) by Trabzon Sanat Tiyatrosu (Trabzon Art Theatre). Directed by Hrant Hakopyan, this production is a rare example of collaboration among theatre-makers from Armenia and Turkey. Even though Trabzon Sanat Tiyatrosu is a small-scale company on the Black Sea coast, Bağdasar Kardeş gained significant visibility because it coincided with Dink's murder. After the assassination, Necati Zengin, the company's artistic director, emphasized how Bağdasar Kardeş facilitates a dialogue between Armenia and Turkey, stating their ultimate goal of becoming the first Turkish theatre company to stage their play in Armenia.Footnote 43 In 2008, the play toured in Armenia, paving the way for other Turkish productions, including the later production of Şark Dişçisi by Nilüfer Belediyesi Kent Tiyatrosu (the Nilüfer Municipality City Theatre) to be staged in Armenia.

After the loss of Hrant Dink, Boğaziçi Gösteri Sanatları Topluluğu (Boğaziçi Performing Arts Ensemble) formed Tiyatro Bağlamında Kültürel Çoğulculuk Çalışma Grubu (the Cultural Pluralism in the Context of Theatre Working Group). The group collaborated with Armenian theatre-makers, scholars and publishers to translate Baronian's works. In 2010, they organized an event consisting of panel discussions and theatrical productions to commemorate Baronian.Footnote 44 At this event, Berberyan Kumpanyası (Berberyan Company), an Istanbul-based Armenian amateur theatre company, and Tiyatro Boğaziçi (Theatre Boğaziçi) co-produced a short version of Adamnapuyj aravelyan in Turkish. The group also published a special issue on Hagop Baronian in the theatre journal Mimesis.Footnote 45 Lastly, two outstanding scholarly works, Mehmet Fatih Uslu's comparative analysis of Turkish and Armenian plays written in the Tanzimat period and Fırat Güllü's study of the representation of system crisis in the Ottoman Empire, analysed Baronian's works as part of nineteenth-century Ottoman literature for the first time, responding to the gap in the scholarship and inspiring further research on the subject.Footnote 46

Adaptation as abjection: the play within a play in Şark Dişçisi

On the play's website, Engin Alkan, the director of Şark Dişçisi, states that he encountered Baronian's name for the first time in Mimesis.Footnote 47 The website includes dramaturgical research on Baronian, Armenian theatre and Ottoman popular performance, as well as two newspaper articles that acknowledge the Armenian Genocide.Footnote 48 The mainstream media, however, disregarded the background of the production and promoted the play as ‘the first production of Hagop Baronyan's Şark Dişçisi in Turkey’.Footnote 49 The play's booklet also emphasizes the production's uniqueness by claiming that İBBŞT staged Adamnapuyj aravelyan in its ‘full text for the first time in Turkish’.Footnote 50 Şark Dişçisi is indeed the first production of Adamnapuyj aravelyan by a professional theatre company in Turkey; however, what happens to the meticulous dramaturgical efforts when the production presents itself as the staging of Adamnapuyj aravelyan in its full text?

The ephemera of Şark Dişçisi does not mention the restoration of the source text, although the director refers to the production as an adaptation. Alkan explains the political significance of staging a widely ignored play and why they refrained from promoting the play as an adaptation: ‘I did not want my name to be mentioned as the adapter because there is a restoration of honour in this case. Until Boğaziçi University presented their research reports to us, we did not know that an Ottoman writer named Hagop Baronian existed’.Footnote 51 The emphasis on Baronian's ‘Ottoman’ identity plays a key role in the production's restorative approach to its source text. Although the production does not immediately present itself as an adaptation, the theoretical terrain of adaptation becomes instructive in analysing the broader political dynamics and ethical dilemmas inherent in the restoration process.

Adaptation is characterized by citationality, intertextuality and re-performance, yet adaptation is first and foremost based on the differentiation from another text in order to be. Julia Kristeva famously describes abjection as constant exclusion, separation and splitting.Footnote 52 Abjection marks the primary steps of the socially constructed understanding of the self-initiated before birth, underlining a continuous differentiation or separation from the mother's – or rather other's – body. Like the subject that cannot be thought of without the other, the adaptation depends on the jettisoning from other texts while being intricately connected to them. This demonstrates how the adaptation process is necessarily political, reflecting the social and cultural concerns of their time as well as the personal motivations of their adapters. Moreover, adaptation retrospectively transforms their source texts by shedding ‘new light onto the initial performance’.Footnote 53 Abjection, while essential for adaptation to differentiate itself from a point of origin, highlights the liminality of adaptation and harbours negotiations embedded in ‘ideological, ethical, aesthetic, and political’ choices.Footnote 54

In the context of the adaptation of a minoritarian text by a mainstream theatre institution, the theoretical framework of abjection not only offers a fresh perspective on adaptation but also informs the role of minorities in the constitution of national identity. National abjection is a process in which the minorities occupy ‘the seemingly contradictory, yet functionally essential, position of constituent element and radical other’.Footnote 55 From this perspective, the minorities participate in the construction of the national self through their constant exclusion. Considering how Şark Dişçisi draws on a shared multicultural and multi-ethnic past that promotes an anachronistic Ottoman identity, a comparative analysis reveals how minoritarian and majoritarian identities are reconfigured onstage.

Adamnapuyj aravelyan's main character is Taparnigos, the infamous ‘oriental’ dentist who cheats on his wealthy but old wife, Marta. Using his visits to so-called patients as an excuse, Taparnigos spends most of his time with a younger woman named Sofi, who also married an older person for upward social mobility. At the end of the play, Marta catches her husband with Sofi. Yet she cannot take action against him because Taparnigos finds a love letter that reveals Marta's former extramarital affair with Sofi's husband. Consequently, the couple agree not to carry this conflict to the Armenian Judicial Council, which was responsible for marriage trials, to protect their reputation. The main plot is also supplemented by a generational conflict that reflects on the theme of false westernization through the opposing characterizations of Markar, the fiancé, and Levon, the secret lover of Taparnigos's daughter, Yerenyag. In contrast to Levon's shallow imitation of Western manners, Markar, as the representative of provincial Armenians, resolves the conflict between Yerenyag and her parents by standing aside in favour of the young lovers. The play thus ends with a dubious resolution, a characteristic ending for Baronian's sociopolitical satire.

Baronian uses the destruction of the family as a metaphor to refer to the broader problems within the Armenian community in Adamnapuyj aravelyan. While portraying the instrumentalization of marriage for social mobility, the play foregrounds how solidarity within the Armenian community came to a halt. The economic and cultural inequality between upper and lower classes, the misinterpretation of westernization as merely following new trends and customs, and the disinterest of the urban ruling class in the problems of economically and politically underprivileged provincial Armenians are thus intermingled in the play's depiction of social corruption.Footnote 56

Şark Dişçisi is a multi-layered reinterpretation of Baronian's comedy that experiments with alternative modes of historiography through the play within a play. Each character thus gets a ‘meta-’identity as a member of the fictional Armenian theatre company named the Oriental Company. The play-within-a-play technique serves the restorative historiographical agenda, foregrounding the role Armenians played in the development of European-style theatre in the Ottoman Empire. By utilizing a fictional theatre company, Şark Dişçisi acknowledges the forgotten Armenian theatre-makers whose names did not reach the present. The fictional actors do not have names other than their characters' names in the metatheatrical layer, which exposes the present absence of contemporary Armenian artists onstage.

Şark Dişçisi opens with the prologue of Kolbaşı, the manager of the fictional theatre company, who directly sets the historiographical atmosphere: ‘The touring theatre, the Oriental Company, and I came to you by breaking away from the past.’Footnote 57 Kolbaşı serves as the narrator, director and background actor in the play, constantly interacting with the audience and intervening in the action onstage. These interventions combine diverse stylistic references from experimental drama to Ottoman performance, such as the storyteller (meddah), emphasizing the amalgamation of traditional and European-style elements in Ottoman theatre.

Kolbaşı's prologue portrays a vague historical background for the fictional Armenian theatre company, reflecting on the glorious days of the Armenian theatrical activities in Pera, the cultural hub of Constantinople, in the mid-nineteenth century. This narrative is not solely fictional; it incorporates accurate and anachronistic details such as the 1831 Pera fire that supposedly burned down the building of the Oriental Company. This is clearly a date too early for the formation of the first professional Armenian theatre companies, highlighting the distorted temporality of Kolbaşı's prologue. The soft background music and the solitude of Kolbaşı on the dark empty stage with a spotlight constitute the bitter atmosphere of the scene. Kolbaşı thus asks the audience whether or not they remember the Oriental Company and tries to remind them by giving the exact address of their building. When he does not receive an answer, he gestures with disappointment and states that they cried a lot when their building burned down, yet they ‘got used to it’. Whispering as if he is giving a secret, Kolbaşı then expresses that, at least now, they do not have ‘the fear of being shut down’. The prologue thus briefly mentions the oppression of theatrical activities in the Ottoman Empire while avoiding any direct reference to historical events. Kolbaşı's emphasis on how they were forced to become a touring theatre company also functions as a metaphor for deportation, directly associated with the events of 1915. Yet these inconspicuous references are followed by a controversial depiction of Baronian.

While speaking with an Ottoman Armenian accent to foreground his Armenianness, Kolbaşı introduces Baronian as ‘an auspicious son of the Ottoman Empire, struggling against injustice and oppression’. Kolbaşı does not identify Baronian as an Armenian playwright, although the production's booklet introduces Baronian as an ‘Istanbulite Armenian’. This depiction holds an anachronistic vision of Ottomanness, reframing the nation's borders by fixing minorities into certain categories of subjecthood. On the other hand, Kolbaşı's words also challenge the contemporary hegemonic imaginary that associates Ottomanness primarily with Islam and Turkishness by framing an Armenian cultural producer as ‘Ottoman’.

Even though Kolbaşı makes a passing reference to the oppressive atmosphere in Baronian's lifetime, Şark Dişçisi refrains from explicit references that would evoke the memory of violence against Armenians. The adaptation largely preserves the theme of false westernization while excluding political references to the Armenian National Constitution. These references in Adamnapuyj aravelyan are directly attached to Markar and his nationalistic discourse. Due to elimination, Markar's characterization in Şark Dişçisi is significantly different from that in Baronian's text. Although Markar is still part of the main plot as Yerenyag's fiancé, his characterization in the adaptation becomes ambiguous vis-à-vis his idealization as a nationalist figure in Baronian's text. While Kolbaşı introduces each main character in the frame narrative, he does not introduce Markar, which confirms Markar's secondary position.

In Adamnapuyj aravelyan, Markar appears as the counterfigure of not only the play's copycat, Levon, but also the main character Taparnigos. False westernization is unpacked through the characters' lack of education, exemplified by Taparnigos's ‘oriental’ techniques in dentistry, such as tying up his patients or removing the wrong tooth. As a self-educated man from the provinces who prefers his ‘old clothes’ rather than imitating Parisian style like Levon, Markar highlights the importance of following the Western mindset of enlightenment.Footnote 58 What makes Markar so central to Baronian's text, however, is reflected in a didactic scene where he shares his ideas on Armenian politics with Taparnigos, which does not contribute to the plot and is completely removed from İBBŞT's adaptation.

In this didactic scene, Markar discusses evoking a nationalist consciousness in the context of the Armenian National Constitution and the role of the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, geographically called ‘Armenia’, before the massacres of the Hamidian era (1894–6) and the Armenian Genocide. He states, ‘We are all the children of Armenia’, to foreground that the roots of the nationalist imaginary are laid in the historical ‘homeland’ of the Armenian community, not in Constantinople, where the constitution was regulated.Footnote 59 Foregrounding the primary role of a constitution and a national general assembly to solve the problems of underprivileged Armenians, Markar contends that ‘the hope for freedom’ might disappear one day because ‘the arms [of the provincial Armenians] are weakening every day’ due to the harsh economic and political atmosphere.Footnote 60 Markar also criticizes the inequality in the representative system of the Armenian National Assembly, which mainly consisted of Armenians from Constantinople, although the larger Armenian population inhabited the eastern provinces.

The references to the Armenian National Constitution in Adamnapuyj aravelyan obtain new meanings today because they necessitate a confrontation with the history of oppression against Armenians and a reminder of how the region's demographics have changed since 1915. The adaptation thus completely excludes this scene because the provincial ‘Armenia’ does not any longer exist in the way it did. If the production attempted to stage this scene without mentioning the Ottoman Empire's and Turkey's share in this loss, Markar's criticism of the Armenian elite would also result in an ethically problematic approach to Ottoman Armenian history. Moreover, Markar's statement, ‘We are all the children of Armenia’, cannot be articulated on the contemporary stage without signifying the famous slogan ‘We are all Hrant, we are all Armenians’ and its political baggage. In this context, the secondary sources on the play's website that directly refer to the Armenian Genocide and elimination onstage reflect the ambivalent political dynamics embedded in the adaptation process.

İBBŞT has a long history as the successor of Darülbedayi-i Osmani (Ottoman House of Beauties), which precipitated the Turkification of theatre.Footnote 61 Darülbedayi-i Osmani was established in 1914 as the first European-style school of music and theatre in the Ottoman Empire. Armenian actors and directors, especially Armenian women, played a vital role in the institution's formative years due to the prohibition of Muslim women from acting.Footnote 62 However, after the transformation of the institution into Şehir Tiyatrosu (the City Theatre) in 1934, almost all actors and directors were Turkish.Footnote 63 Moreover, the institution's magazine, Türk Tiyatrosu (Turkish Theatre), contributed to the Turkish-history-thesis-oriented theatre historiography in the early Republican period.Footnote 64 Despite the exclusion of references to Armenian nationalism, the play within a play in Şark Dişçisi thus enables a confrontation with the public theatre's history in a self-reflexive manner. The intertwined temporalities of the plot of Adamnapuyj aravelyan, the fictional Armenian theatre company's enactment of this play, and the Turkish actors' staging of Şark Dişçisi ultimately mark the absence of Armenian theatre-makers in public theatres and bring them back at the level of representation.

Theatre as a ‘memory machine’: stylistic approaches to ghosting

The sedimented temporality reflected through metatheatricality in Şark Dişçisi and the play's thematic engagement with collective amnesia and minoritarian memory evoke the idea of theatre as a ‘memory machine’ in which ‘ghosting’ becomes the first principle.Footnote 65 The notion of ghosting, or hauntedness, refers to the operation of theatre through continuous re-enactment without holding the quality of representing something for the first time. Marvin Carlson argues that theatre functions ‘as a repository and the living museum of cultural memory’ due to its temporally compact form that requires repetition and recycling.Footnote 66 Considering how both theatre and adaptation build on repetition and citationality – or, in Hutcheon's words, ‘recognition and remembrance’ – the stylistic choices made during the adaptation process in Şark Dişçisi familiarize the unrecognized source text.Footnote 67 Meanwhile, the conceptual framework of ghosting sheds light on the adaptation's double-edged relationship with the official historiography.

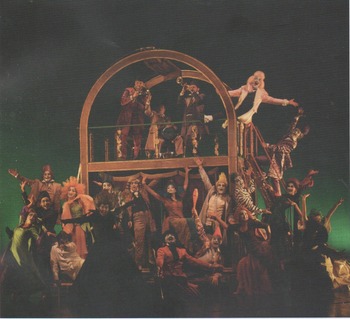

Şark Dişçisi utilizes familiar elements to make the source text more accessible to contemporary audiences in eclectic ways. The play juxtaposes historical materials and grotesque style in costume, make-up and set design, while also utilizing the Ottoman Armenian accent. The juxtaposition of historical, anachronistic and grotesque styles reveals how the play does not aim for a conventionally realistic representation; rather, it experiments with history and storytelling. The main set design consists of a moveable outdoor stage that borrows the common image of a pageant wagon from European theatre history (Fig. 1). This common image is accompanied by props with historical and local connotations, such as oriental carpets or Turkish coffee, referring to the mixed roots of Ottoman theatre. The chariot stage enhances the effect of metatheatricality, as the actors constantly change the set and even stop the play by stating that they are not ready yet.

Fig. 1 The set design by Cem Yılmazer consists of a moveable outdoor stage that re-creates a common image of a touring theatre company. İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Şehir Tiyatroları, 2011. Photograph by Selin Tuncer and Ahmet Çelikbaş. Photograph retrieved from Şark Dişçisi Oyun Kitapçığı. Courtesy of İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Şehir Tiyatroları.

Şark Dişçisi does not specify the time for the frame narrative, which also explains why many elements are taken from different forms of performance practice. The production detaches fixed connotations of historical objects through its overarching grotesque style. Familiar elements are accompanied by grotesque style in costume, such as the use of the iconic nineteenth-century headdress, the fez, and Cirque du Soleil-fashion make-up (Fig. 2). The costume and make-up design add another layer to the pseudo-historical narrative in Şark Dişçisi, foregrounding how European-style theatre and Ottoman popular performance genres did not emerge separately but rather their histories are also entangled. The messiness of the style can be read as a challenge to the normative methodology in historiography and as a celebration of memory's heterogeneity. Kolbaşı thus blurs the historical background of the Oriental Company: ‘I see some of you are wondering about my age. I cannot tell you my actual age, sir, but if you ask me my theatrical age, I can tell you this: I am as old as your oldest dream, as young as your most youthful enthusiasm’. Kolbaşı reframes the fictional theatre company as part of not only Turkish but also global theatre history by referring to the ancient roots of theatre. The temporal disorientation also evokes the play's thematic use of ghosting.

Fig. 2 The costume design by Tomris Kuzu for the characters Yerenyag and Taparnigos exemplifies the play's juxtaposition of historical and grotesque elements. İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Şehir Tiyatroları, 2011. Sketch retrieved from Şark Dişçisi Oyun Kitapçığı. Courtesy of İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Şehir Tiyatroları.

The most important element that contributes to ghosting is the use of the historical Ottoman Armenian accent. Like other ethnic minorities, Armenians of Constantinople were mostly bilingual, and they spoke Turkish with the characteristics of the Western Armenian dialect. Even during the nineteenth century, the Armenian theatre-makers’ ‘improper Turkish’ was criticized by the Turkish nationalists.Footnote 68 After the emergence of Turkey as a nation state in 1923, the standardization of language, along with the aim of creating a homogenized ‘Turkish’ society, aggravated new oppressive politics regarding multilingual social life. The language policies, as well as the diminishing number of Armenians living in Turkey, led to the gradual change in the Armenian accent of Turkish; hence the accent in Şark Dişçisi is not currently in use.

Şark Dişçisi refers to the loss of Armenian linguistic heritage in an additional scene in which Markar sings a love song in Armenian after he learns about Yerenyag's secret relationship. With its pitch-dark atmosphere, this scene contrasts sharply with the preceding colourful farcical scenes. Before Markar begins his song, background characters change the setting into a meyhane, a traditional bar, and Kolbaşı serves the famous local alcoholic beverage, rakı, to Markar. Markar then starts to sing a love song in Armenian and later repeats the song's last words in Turkish to enhance the familiarity of the song's theme for Turkish-speaking audiences. By adding an emotional scene in which Markar sings a sad love song in Baronian's situation comedy, as well as utilizing the Armenian accent, the production thus evokes the ghosts of Armenian theatre-makers. However, another issue to be addressed is that while Armenian accent coaches trained the cast, Armenian artists were not recruited for the play, not even as subcontractors.Footnote 69 The recruitment process and the dramaturgical preferences are directly linked to the institutional organization of İBBŞT as well as to the political pressures on artistic production under the rising authoritarianism in contemporary Turkey.

İBBŞT has always been subjected to governmental impact as a public theatre, even though the institution enjoyed ‘semi-autonomous status’ with the dominance of artists in management.Footnote 70 Since full-time employees of public and state theatres in Turkey are civil servants – therefore prohibited from participating in political activity and obliged to ‘remain loyal to the Turkish Nationalism as expressed in the Constitution’, it is no surprise that public theatre productions cannot openly criticize the nation state's official historiography, let alone speak of the Armenian Genocide.Footnote 71 At the same time, the civil servant status of the artists gives them job security, which became a big issue in the context of the AKP's smear campaign against public and state theatres. A regulation crisis in İBBŞT marked the early 2010s due to the AKP-governed Istanbul Municipality's implementation of a new regulation that made drastic changes in İBBŞT's management. In 2012, the new regulation replaced the artistic director with the head of the Department of Cultural and Social Affairs of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and transformed the institution's executive board into a ‘bureaucratic and political body’ dominated by appointed bureaucrats instead of elected artists.Footnote 72 The tensions between the AKP-governed Istanbul Municipality and İBBŞT later resulted in the dismissal of six artists and accusations of their being involved in the 2016 coup attempt, including Sevinç Erbulak, who played Yerenyag in Şark Dişçisi.Footnote 73

A closer look at Turkish public and state theatre productions that employ Armenian memory narratives with a manifest aim of the ‘restoration of honour’ shows that these productions are stuck with a historical representation of Armenians. Although this trend is not necessarily intentional, embracing the ghost of Armenian theatre-makers does not equate to all-inclusive representation. Şark Dişçisi's contributions to the politically progressive countermemory movement under institutional pressures show how representation includes the potential for both repression and emancipation.

Conclusion

Şark Dişçisi presents a unique case study for investigating the political tensions in theatre, leading us to questions regarding the ambiguous and, above all, precarious position of minoritarian memory in the context of a mainstream theatre institution. During the years when Şark Dişçisi was onstage, İBBŞT had twelve theatres located in different parts of Istanbul and even had a broader audience than İstanbul Devlet Tiyatrosu (the Istanbul State Theatre).Footnote 74 The play was still in the repertoire in the 2014–15 season, when İBBŞT celebrated its centenary with a special programme. The staging of Şark Dişçisi in that year has another symbolic value since it was also the centenary of the Armenian Genocide. After İBBŞT, Şark Dişçisi was staged by another public theatre in Bursa in the 2016–17 season, with a new cast.Footnote 75 The production won several theatre awards in different categories over the course of six years and even toured in Armenia, partially accomplishing its aim of revitalizing the memory of Hagop Baronian in and beyond Turkey. Hence, even though the adaptation eliminated the nationalist undertones of Baronian's Adamnapuyj aravelyan, it enabled Armenian history and culture to become relatively more visible.

Abjection is at the core of the adaptation process, continuously negotiating, challenging, forming and transforming the borders of the adapted text and the source text, or perhaps the mainstream and the minoritarian. Even when staged to pay tribute to neglected Armenian theatre-makers, Şark Dişçisi cannot escape being influenced by the ambivalences of post-Genocide memory work in Turkey. Doubtless, the tense political atmosphere in Turkey affects all theatre-makers; however, the government's interference is deeply ingrained in subsidized theatre's institutional organization. Şark Dişçisi thus focuses on another layer of Armenian memory that would not directly appear incompatible with the official Turkish historiography, namely the erasure of Armenian theatre-makers from mainstream historical narratives. While the common tendency of staging revisionist theatre historiography in public and state theatre productions functions in diverse ways (including genocide denialism in some other plays, such as Kantocu), Şark Dişçisi exemplifies how political tensions and progressive agendas intersect in artistic production.

In contemporary Turkish theatre scholarship, ‘political theatre’ and ‘the explosion of memory’ have been widely associated with independent theatres that have increased in numbers in the last two decades.Footnote 76 However, as the case of Şark Dişçisi points out, public theatre productions also partake in these efforts, although mostly in subtle ways. The institutional structure of İBBŞT thus not only influenced the elimination of political references in Baronian's Adamnapuyj aravelyan, but also provided resources to reach diverse audiences and even transmit the politically progressive agenda through other media, such as the play's website. At the juncture of representation and re-presentation of exclusion, a comprehensive analysis of independent and public theatre productions on minoritarian memory thus becomes indispensable.