Introduction

Digital collection projects should be used as a strategy to develop collections that are of interest to the local or global community as they complement the commercially-available published content that libraries license or purchase and the open content libraries make discoverable. However, digital collection projects are sometimes considered niche or peripheral. In addition to the art library's special collections, exciting and relevant content ripe for inclusion in digital collections may be held outside of the library by patrons or constituents. It is the responsibility of the art librarian to showcase this library service and the library's capabilities to stakeholders who may own content. This method of building collections for worldwide access strengthens the art library's relationships with faculty, researchers, alumni and departments and builds on the traditional identity of the librarian as content providers to the more active content producers, and these expanded relationships continue to move the dial from librarian as service provider to librarian as collaborator.

Through a close examination of the UC San Diego Visual Arts and Architecture Digital Collections, this article will review the context of the UC San Diego Library's Digital Collection including the tools leveraged to create a successful digital library environment and the importance of cultivating relationships with content donors, including challenges and opportunities. Marketing and publicity of digital collections as part of the project lifecycle will also be discussed. And finally, the importance of advocating for arts content within the library's digital collection will be explored.

Context

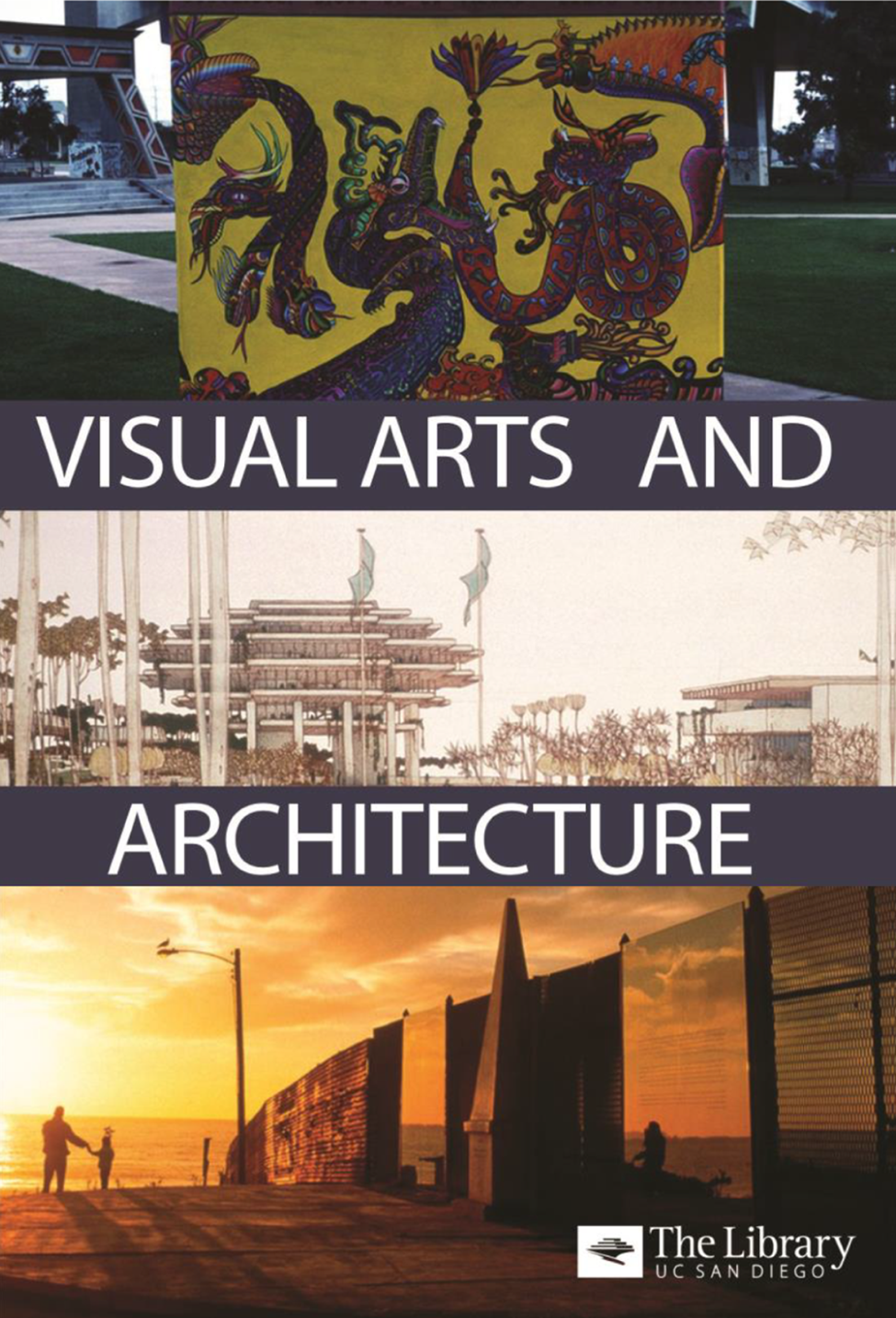

The Visual Arts and Architecture Digital Collection at UC San Diego was launched in June 2018 after a two-year development period. ‘This collection includes images, films, audio, and documentation of Southern California and Border Region art, architecture, and urban development. While the collections are distinct in nature, researchers will find common themes of performance, installation, public art, and the built environment.’Footnote 1 Digital Libraries projects are a priority at UC San Diego. The UC San Diego Digital Collection features over 100,000 objects including sound, image, video, and text on subjects reflecting the strengths of our collection from California history to marine sciences to Dr. Seuss. Librarians are expected to be project leads on Digital Collection projects in their respective disciplines. Projects come to librarians in a variety of ways, some are solicited, and some are assigned by a Digital Projects Committee. Projects are evaluated based on a number of factors including impact on teaching, research and learning and historical and cultural value.Footnote 2 Each project has a different timeline or length of development, for a variety of reasons including size of collection, metadata creation requirements, and securing permissions, some projects progress more quickly than others. Not all arts librarians have experience with digital projects, digital libraries, or digital collections and some libraries do not have a digital libraries infrastructure. Arts librarians may have experience with visual resources collections and teaching collections but not unique content.

Fig. 1 UC San Diego Library, Visual Arts and Architecture Digital Collection.

Tools

UC San Diego Library is an institution widely-known for its early Digital Asset Management System (DAMS) development.Footnote 3 We have a locally developed system within the Samvera community.Footnote 4 In addition to DAMS infrastructure, the success of digital projects at UC San Diego rely on several tools including Chronopolis, the geographically dispersed digital preservation network developed by UC San Diego and partner institutions, funded in part by the Library of Congress and the Mellon Foundation.Footnote 5 For discovery and access, the Digital Collection is searchable through CalisphereFootnote 6, a repository of over 200 institutions throughout California, and the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).Footnote 7 In addition, the UC San Diego Library uses tools such as JSTOR ForumFootnote 8 as a tool for content providers to contribute and review metadata.

Why Digital Collections?

In the article “Library Collections in the life of the user: two directions”, Lorcan Dempsey describes the ‘inside-out’ model of library collections: ‘the university, and the library, supports resources which may be unique to an institution, and the audience is both local and external. The institution's unique intellectual products include archives and special collections, or newly generated research and learning materials…often the goal is to share these materials with potential users outside the institution.’Footnote 9 This inside out model acknowledges the importance of unique digital collections and furthers the notion of a more holistic consideration of developing and building arts research collections. A holistic, three-pronged approach includes purchasing and licensing commercial content, curating open content and making it discoverable, and developing unique digital collections based on institutional and geographic strengths. Most librarians find themselves in a situation with a flat budget therefore funding to purchase and license content is limited, while having to confront rising costs of commercial serials content, more monograph content published each year, and more commercial digital primary source content becoming available. Librarians need to continue to develop collections and if the infrastructure is available, in this fiscally restrictive environment, building digital collections is a creative approach to collection building.

Identifying and advocating for digital collection projects

Digital collections projects can develop from an existing relationship with a constituent or a new relationship. For example, a visual arts faculty member may have a long-term relationship with a librarian, building the collection in their area of research, integrating information literacy into their courses, referring their students for one-on-one research consultations. Then, it occurs to the librarian that digitizing and making available the visual arts faculty member's artwork through the library DAMS may be an important step that is mutually advantageous. The faculty member benefits from the long-term preservation and content discoverability, the library and ultimately researchers benefit from access to this unique content. As scholarly communication develops and alternative forms of publishing are recognized as researcher output, faculty are highlighting their work in new ways, and the library demonstrates that it is offering additional services that support the scholarly communication lifecycle in the arts. Once you have identified a viable project, next comes advocating internally as most of us have limited resources, collections policies and a proposal process. Identifying a focus to your digital collection building is critical. The UC San Diego Visual Arts & Architecture Collection has a regional focus, as well as themes of border arts, land art, and underrepresented voices. The two collections that are closely scrunitzed in this article are tied to these themes. The first case will focus on metadata and the second on publicity and outreach.

Collection focus on metadata: University Art Gallery Closure Events 2016

In 2016, the University Administration at UC San Diego threatened to close the University Art Gallery (UAG). During the year, Collective Magpie and Friends Collective, two artist collectives organized 20–30 events protesting the closure. Collective Magpie and other artists associated with UC San Diego, including undergraduate students, graduate students, and faculty documented the events with moving and still images. Due in part to their efforts, the University Art Gallery remains open today.Footnote 10 Collective Magpie reached out to the visual arts librarian because they felt that this was an important project that was documented during their tenure, they were concerned about the projects’ memory in the context of the history of the Gallery and the history of the arts at UC San Diego. This digital project is a significant addition to the UC San Diego Digital Collection not only because it documents the history of the University Art Gallery, but it is also essential because it is a social justice project and one that focuses on underrepresented voices. It reveals and highlights the tension between the University Administration and the artists. The space that was being closed was critical to the exhibition of artistic work created by affiliates of the Visual Arts Department. As we discuss and act on issues related to equity, diversity and inclusion, collection building is one aspect of several. To ensure that library collections truly do reflect the profession's stated commitment to diversity, academic librarians must actively and aggressively collect resources by and about underrepresented groups.Footnote 11

Fig. 2 Facade of the UCSD University Art Gallery with signs and graffiti drawing attention to the gallery's imminent closure, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb7581510v.

The librarian acts as the project manager and curator for digital collection projects and each project may have a unique set of circumstances that add layers of complexity. The UAG project was fraught because it was political and polarizing. Advocating for the other voice within the hierarcy was a challenge but because UC San Diego celebrates and supports equity, diversity, inclusion and nontradition, it felt less threatening.Footnote 12 Another role that the librarian assumes in successful projects is the connector or conduit. There are many contributors to such a project and the librarian brings all of their work together.

The UAG Closure project and other visual content projects rely heavily on the donor for the most accurate information about each asset. For this project JSTOR Forum was leveraged as a tool for the donors to enter preliminary metadata or descriptive information about the item such as the title, date or subject matter. Then a metadata specialist works closely with the data to clean up the contributions, standardize the language, assign topics subjects and/or descriptors, and provide context. Working together, the content provider and the metadata specialist create the most robust description. This project resulted in 141 digital images and is complemented with a small web archiving projectFootnote 13 to ensure that the press documenting the events in the media were also preserved. Five webpages are captured and preserved in Archive-ItFootnote 14 and an access point is available in the library catalog and Worldcat.Footnote 15

Digital collection projects sourced from newly acquired donor content have both challenges and opportunities. Similar to the relationship between librarians and donors of analog collections, managing expectations related to the processing timeline and project completion to presenting an end product that proves pleasing and worthwhile to all involved, it can very much feel like a client-contractor relationship. Digital library projects can take 12–24 months in most cases and librarians are beholden to the project workflows, infrastructure and tool limitations. Once a project becomes publicly available, it often times it seems like it is time to move on to the next project, but publicity and outreach should not be overlooked.

Collection focus on publicity: Slab City

From about 1986 to 1992 videographers Sherman George and Greg Durbin shot footage of the Sonoran Desert community of Slab City (Imperial County, California) for a documentary that was never realized. These videos and images numbering 234 digital objects include extensive interviews with residents, various community activities (swap meets, holiday parties etc.) and many shots of the surrounding desert landscape and military bombing range.Footnote 16 Slab City is an off-the-grid community unregulated by the government or private interests. As a result several artists’ projects have been created including Leonard Knight's (1931–2014) Salvation Mountain, a folk project, and East Jesus, an outdoor art installation.Footnote 17 This regional digital collection content is of interest to researchers studying folk or outsider art, land art or earthworks, DIY and desert communities. In Southern California, Slab City and Salvation Mountain are fairly well known and these areas of research are popular. Because of the transient nature of the Slab City enclave as well as the inherent off-the-grid mentality, it has been challenging to publicize the digital collection to those who could have the largest impact on the use of the collection. Once the collection is publicly available, it is time to turn to publicity and outreach. The librarian should ensure use of the collections that took valuable resources to develop. It is the responsibility of both the librarian and the donor to spread the word about the collection. At UC San Diego, we believe in an approach that includes both the physical and digital. Postcards and/or bookmarks are developed to share with current our users and potential collection users. These postcards are brought to library instruction sessions, orientation and outreach events, and one-on-one meetings with a faculty member that may be interested in using the content in their curriculum. Wikipedia articles are also enhanced through project manager contributions, see the Slab City and Salvation Mountain Wikipedia articles as an example. And there are times that going the extra distance may be worth it too. Because names and addresses of those that live in Slab City year round are not easy to obtain, in 2018, three librarians and library staff involved in the development of the collection drove over 300 miles round trip, out to Salvation Mountain and Slab City to let the people who live out there know that the digital collection was now available. Face to face communication regarding the collection seemed to be an effective strategy. The librarians distributed stacks of Slab City postcards to several contacts made on the ground on that day in November hoping that these individuals would let other interested parties know about the digital collection. Ideally, visits to Slab City would be an annual or biennial occurrence to keep awareness of the digital collection ongoing.

Fig. 3 Slab City: photograph of army guard house, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb8738866q.

Conclusion

In David W. Lewis's article “From Stacks to the Web: The Transformation of Academic Library Collecting”, he states ‘the most difficult [issue] will be to get subject librarians to drop traditional collection building activities and replace them with activities that engage with the faculty to build digital collections.’Footnote 18 Art information specialists should prove Lewis mistaken. For 20 years, art librarians and visual resources curators have been working with faculty to build digital collections. The shift has been from rote teaching collections to the unique content as is featured in this article. Art librarians should lead the development of digital collections at their institutions. They have in-depth experience with digital asset management, metadata creation, image quality assessment, and copyright and licensing. Art librarians and visual resources curators have decades of experience working with faculty to build image collections, at one time these collections were analog slides, but this is the foundation for the work art information professionals are now doing in the digital environment. In addition, the content is usually graphically rich and adds visual appeal to the larger collection. Now is the time to have discussions with faculty, graduate students and other constituents that may have content to add to your institution's digital library content that is unique and will be of interest both locally and globally. The future of collections building is holistic, along with purchasing and licensing commercial content and making open access content discoverable, developing digital collections is an essential part of the whole. This holistic approach in turn informs the other responsibilities we have as librarians. The primary source content that a librarian has curated and managed is now leveraged as a research and teaching tool for local and global constituents. Therefore the benefits of building collections go beyond the librarian's responsibility developing collections but they represent and bring together the various aspects of the librarian's portfolio from collection development to teaching to research. The Visual Arts & Architecture Collection at UC San Diego is the foundation to presenting interesting and compelling primary source digital content in the arts. This project epitomizes the power librarians have to preserve and make content available now and in the future.

Fig. 4 Postcard: UC San Diego Library, Visual Arts and Architecture, Digital Collection, front.

Fig. 5 Postcard: UC San Diego Library, Visual Arts and Architecture, Digital Collection, back.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a paper presented at the 50th Annual Conference of ARLIS UK & Ireland in Glasgow, Scotland, July 15, 2019. I would like to acknowledge Cristela Garcia-Spitz, Digital Initiatives Librarian for her digital collections support and encouragement and for reviewing the content of this article.