This article assesses Quebec's cultural policies and bioarchaeological practices within the context of Indigenous repatriation and rematriation claims. It follows the work of Paquette and colleagues (Reference Paquette, Ribot, St.-Pierre, Zachary-Deom and Nolet2021), which was initiated by the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake (MCK) to build a database on Indigenous human remains discovered in the province: as the first such database, it was a major advance for Quebecois bioarchaeology. During its first phase, the database recorded 239 sites with archaeological human remains. Nevertheless, missing information regarding both the specific origin (Euro-Canadian versus Indigenous) and the current location of archaeological human remains remained a serious obstacle to initiating repatriation and rematriation processes. A second phase was initiated in 2021 to provide further information on the Ancestors’ current location (Martin-Moya Reference Martin-Moya2022).

The purpose of this article is not to present detailed information about the database. Instead, it is to to explore the challenges met while building it and to reflect on (1) the mechanisms of bioarchaeological practice in Quebec; (2) how various Canadian institutions manage archaeological human remains; and (3) past, current, and future practice regarding the Indigenous cultural heritage in Quebec. It highlights the legal and moral obstacles facing Indigenous communities when engaging with repatriation and rematriation processes.

Non-Indigenous institutions have ruled the legal system and its bureaucracy since colonial times, in addition to arbitrating Indigenous heritage (Redman Reference Redman2016; see also Colwell Reference Colwell2021). As has been well recognized, policies and projects developed by the Canadian government cannot be disentangled from colonialism (Coulthard Reference Coulthard2014; Manuel and Derrickson Reference Manuel and Derrickson2018). By “colonialism,” we mean the ongoing land dispossession of Indigenous communities by colonial institutions to extract their resources for the benefit of the few. Over the years, colonialism gave (bio)archaeologists legitimacy to gather goods, knowledge, and ancestral human remains from Indigenous communities. As a result, Ancestors were massively exhumed from the land and not systematically analyzed with the consent of Indigenous communities. In this article, we use the term “Ancestors” when referring to ancestral Indigenous human remains.

Struggles for Indigenous recognition led the Canadian federal government to promote a new “reconciliation” narrative with Indigenous communities (Coulthard Reference Coulthard2014; Manuel and Derrickson Reference Manuel and Derrickson2018). The recent “rediscovery” of residential schools’ cemeteries such as Kamloops (Gabriel Reference Gabriel2021) led to the passage and implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) Act (albeit in a watered-down state) by Canada in 2007,Footnote 1 as well as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's recommendations in 2015.Footnote 2 However, Ancestors’ repatriation and rematriation processes still constitute a legal Kafkaesque situation for Indigenous communities. There is no federal law or heritage legislation protecting or caring for human remains and funerary materials in Canada as there is in the United States, where the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was passed in 1990 (Kakaliouras Reference Kakaliouras2008). In Canada, heritage management falls under the provincial and federal government's informal regulations made in “good faith” and applied on a case-by-case basis to land claim settlements (Hanna Reference Hanna2005; Lessard Reference Lessard2021; Meloche Reference Meloche2014).

Over the years Canadian institutions have addressed the repatriation and rematriation of Ancestors through various means such as the following: (1) provincial legislation, as in Ontario (Cemeteries Act, revised 1990Footnote 3) or Alberta (First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act, revised 2000Footnote 4); (2) museum guidelines (Assembly of First Nations and Canadian Museums Association, 1992) and internal policies (e.g., Royal Ontario Museum and Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia; see Meloche Reference Meloche2014); (3) centralized management (The Room, Labrador-Newfoundland); and (4) guidelines based on published examples of successful repatriation (Pfeiffer and Lesage Reference Pfeiffer and Lesage2014; Whittam Reference Whittam2015). Compared to Quebec, First Nations in other provinces such as British Columbia have greater decisional power over their ancestral heritage (Meloche et al. Reference Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020). Still, many Ancestors remain out of their graves, because Canadian institutions have mostly adopted a passive approach toward returning them to their descendants. The difficulties of claiming back Ancestors and navigating complex legal steps have hindered Indigenous communities in their repatriation and rematriation requests.

In Quebec, very few claims have been legally filed to rebury Ancestors after they were excavated (e.g., in only four of 345 sites; Martin-Moya Reference Martin-Moya2022). Many more still need to be sorted out (e.g., Deer and Johnson Reference Deer and Johnson2020; Marchal Reference Marchal2021). Indeed, to file such claims, Indigenous communities first need to be aware that Ancestors have been uncovered; second, they need to know how many were exhumed and where they are stored. They can then initiate a request with the owner, whose internal policies are governed by their own legal mechanism (Bell and Patterson Reference Bell and Patterson2009; Hamilton Reference Hamilton2020). In general, only archaeologists and other professionals working in heritage-related issues can access reports through Quebec's Ministry of Culture and Communication (MCC) web portal (Ministry of Culture and Communication [MCC] 2022a). Even then, however, only a few reports and filing systems in Quebec indicate the Ancestors’ location, whether they were left in place or reburied, or whether they were transferred to another place for further analyses. Why are so many Ancestors out of their graves? Why are Ancestors so difficult to locate? How could so many be lost? Why have Canadian institutions not updated their inventories with archaeological human remains?

This article complements the general literature on issues related to Ancestors’ excavation and return claims in Canada. It is the first one to critically reflect on such issues in Quebec and to suggest ways forward by drawing on the reciprocal relationship that we Indigenous and non-Indigenous authors have built; such a relationship is essential if Quebecois bioarchaeology is to be transformed. After describing Ancestors’ legal status in Quebec, we explain how we updated the first database built by Paquette and coworkers (Reference Paquette, Ribot, St.-Pierre, Zachary-Deom and Nolet2021); we then present how and what difficulties arose while attempting to locate Ancestors given Quebec's history of heritage management and bioarchaeological practices. Third, we discuss the Canadian “good faith” case-by-case approach and how it contributes to slowing repatriation and rematriation processes. We draw on our collaborative experience during this project to suggest that a reciprocal approach such as the one developed here between non-Indigenous and Indigenous people is an ideal approach for decolonizing bioarchaeological practices in Quebec (Atalay Reference Atalay2012; Simons et al. Reference Simons, Martindale, Wylie, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020).

Ancestors’ Legal Status in Quebec

Building and updating a database of archaeological human remains—including but not limited to Ancestors—raised many issues that we first addressed by skimming through the relevant legislation. We then cross-checked our understanding of Quebec's various legal frameworks relevant to archaeological human remains with representatives from both provincial (Quebec's MCC) and federal (Parcs Canada) archaeological departments.

Archaeological Practice in Quebec

Since 1972, the Ministère des affaires culturelles (Ministry of Cultural Affairs; MAC), later renamed the MCC, has centralized all information pertaining to archaeological fieldwork (excavations and surveys).Footnote 5 It issues mandatory archaeological research permits to work on public and private land. Archaeologists have one year following the delivery of their permit to file their report and all related information, such as detailed inventories, photographs, field notes, and specialized analyses, with the MCC (2022b). All reports, as well as those containing discoveries about the Ancestors, can be accessed through the MCC web portal and through the Inventaire des sites archéologiques du Québec (Inventory of Quebec Archaeological Intervention; ISAQ) by archaeologists and professionals working on heritage-related projects. These reports must be written in French, which further limits access to non–French-speaking Indigenous communities. Waters and some lands within the Quebec province are managed by the federal government. Archaeological excavations on those lands are managed by Parcs Canada, which has, like the MCC, its own collection storage units and inventory of archaeological reports (Parcs Canada 2022). Both the MCC and Parcs Canada follow similar procedures to promote archaeological investigations when an area scheduled for development has some archaeological potential.

Reviewing the Laws

When human remains are accidentally discovered, the main course of action is to follow Article 182 of the Criminal Code in the Canadian constitutionFootnote 6 (Parcs Canada 2022). If the coroner identifies human remains as archaeological, Article 951 of the Civil Code of Quebec (1991) stipulates the following: any archaeological find (artifacts or human remains) is considered to be a “treasure,” and its discoverer becomes its owner; if the discovery is made on someone's private land, half of it belongs to the finder unless stated otherwise (Brierley Reference Brierley1992).Footnote 7 Owners are encouraged to share their discoveries and their ownership with an organization that can store the finds adequately, such as a government agency, historical society, university, or museum. Unlike other provinces (e.g., British-Columbia Heritage Conservation ActFootnote 8), Quebec does not have written criteria for determining whether human remains are archaeological. Until recently, it was customary to classify all finds dating before 1950 as “artifacts” (MCC, personal communication 2021). Today, an archaeologist must justify the significance of a find to the MCC along seven “value” axes (MCC and Direction de l'Archéologie et du Développement Culturel Autochtone 2022) for which few objective criteria have been clearly specified.

Nevertheless, if archaeological human remains are considered inappropriate to be traded because of their nature, Article 2876 of the Civil Code grants the MCC, under the Cultural Heritage Act (2011), the power to classify a site and to prevent discoveries from being transported or altered without its authorization under Article 29. The MCC can only act on classified areas. If the site has just been recently declared, the MCC plays only an awareness-raising role under the Heritage Act of 2011 (Kolhatkar et al. Reference Kolhatkar, Trudel-Lopez, Rousselle, Gervais and Gagné2020). Because this procedure relies only on the interpretation of the Civil Code, it is difficult to assess how many Ancestors are owned by third parties. Parcs Canada's own guidelines to manage archaeological burials were put in place in 2000 (Parcs Canada 2000). Its main rule is that human remains should be recorded on-site and are not to be removed unless required by circumstances such as vandalism or for public health or safety.

Canadian Guidelines for Indigenous Consultation

After several years of legal battles, the Supreme Court of Canada reviewed its standards for consultation processes with First Nations and Inuit for the recognition of their ancestral rights in 2008 (e.g., the Oka Crisis of 1990). Since 2011, the MCC has had the obligation to notify First Nations and Inuit before excavating ancestral lands. Consultations with Indigenous communities on “non-Indigenous” lands are not required but are strongly recommended (Assemblée des Premières Nations 2007; Gouvernement Québec 2008; Québec-Labrador Assemblée des Premières Nations 2019). The goal of a consultation is to find a resolution that is “mutually satisfactory” for the next of kin or culturally affiliated groups, the governments, and the contractors. Most of the time, potential problems are resolved in the early phase of a development project, thereby avoiding Indigenous backlash and preventing additional costs for the contractor (Coulthard Reference Coulthard2014; Manuel and Derrickson Reference Manuel and Derrickson2018; McFarlane and Schabus Reference McFarlane and Schabus2017).

Parcs Canada and other provinces, such as British Columbia and Alberta, have followed the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) process since implementation of the UNDRIP Act in 2007. However, it was not until Canada endorsed the UNDRIP Act in 2021 under Bill C-15 that it became a standard procedure (Governments of Canada 2022). Currently, before beginning any development project involving Ancestral lands or Indigenous history, goods, or knowledge, it is mandatory to contact any community that could be affected due to its geographical and historical proximity. The FPIC requires that (1) communities be informed (2) without coercion, manipulation, or intimidation, (3) and sufficiently in advance before an excavation to certify that a dialogue is held in good faith (Governments of Canada 2022). If a project is not conducted on lands deemed Ancestral or Indigenous, the government does not need any authorization before proceeding; the FPIC process is not a “veto” given to Indigenous communities, but is mostly used to consider any sensitive matters that may arise and how to handle those issues in a “meaningful” way. This process has not yet been implemented in Quebec (MCC, personal communication 2022).

If there is no clear cultural affiliation, the group (or groups) that is “culturally” similar and nearest to a site should be notified. Geographical boundaries are not clearly delineated, and it is up to government officials to decide which groups to consult in relation to a project. Broad geographical boundaries have been defined with the help of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources and of the Secretary of Indigenous Affairs. The former ministry has mapped all claimed territories, and the latter will mediate any political problems that may arise (MCC, personal communication 2022; Parcs Canada, personal communication 2022).

Building a Database: How Many Ancestors Have Been Excavated in Quebec?

Paquette and colleagues (Reference Paquette, Ribot, St.-Pierre, Zachary-Deom and Nolet2021) built their database from various sources, such as filed reports and articles behind paywalls. It showed that 239 archaeological sites with archaeological human remains of potential Indigenous affiliation (corresponding to a minimum of 678 individuals) had been discovered in Quebec. However, storage locations of the remains were identified for only 51 sites because of poor documentation. Storage locations for only nine of these 51 sites could be further confirmed.

The next step was to locate these remains. The MCC granted our request to access information in their ISAQ database about archaeological fieldwork mentioning human remains. The database contained 127 archaeological sites (updated between 1920 and 2018), which included (theoretically) all archaeological human remains grouped in two population categories (“Amerindians” and “Euro-Canadians”) and three historical periods (postcolonial, colonial, and historic). Only 64 of the 127 sites had complete information regarding potential origin and current location. The MCC database and other documents (including personal communications) were cross-checked with that built by Paquette and colleagues (Reference Paquette, Ribot, St.-Pierre, Zachary-Deom and Nolet2021). To find the missing information, we emailed 23 institutions that may have stored archaeological human remains asking if they had the specific archaeological collections indicated on the ISAQ database or any other archaeological collection with human remains in their storage space (Supplemental Text 1). Two institutions allowed us to visit their collections to verify the presence of human remains. We redacted the names of the institutions and personal contacts. Bioarchaeologists and the MCK were involved in the exchanges with and visits to Canadian institutions.

For the missing entries in the MCC database, we were only able to identify with certainty half of the sites with archaeological human remains; the remaining sites still need to be confirmed. In addition, the MCC database was missing many bioarchaeological sites found in the Paquette database. We added 106 entries to our final pooled database, resulting in a total of 345 sites with archaeological human remains; however, we could not account with certainty for the number of individuals in each site. Of the 345 sites, 228 sites were identified as Indigenous, 77 as Euro-Canadian, and the remaining 40 had unknown affiliations due to a disturbed or missing archaeological context (Figure 1). Unfortunately, no information at all (besides a mention in passing) was obtained for 49 archaeological sites (78% of Indigenous origin, 20% of Euro-Canadian origin, and 2% of unknown origin). Reports from 28 sites with no human remains mentioned the term “burial,” and some zooarchaeological reports that referred to dog burials confirmed the absence of human remains. Finally, our study managed to increase the number of known storage locations of human remains from only nine sites to 146 sites.

Figure 1. Histogram of revised number of archaeological sites having variable information on the place of deposit and origin of the archaeological human remains.

To sum up, we now know the location for 35% of 228 indigenous sites, 70% of 77 Euro-Canadian sites, and 30% of 40 sites of unknown origin (Figure 1). Unknown affiliations could belong to Indigenous sites, but further analyses are needed to determine their biological origin; for example, where skeletal remains are too fragmented, proteomics might help uncover the presence of additional human remains. Assessing the minimum number of individuals per site was difficult because 64% of the Indigenous sites and 17% of the sites with unknown affiliation have no archaeological data inventory (n = 69 reports). Out of 678 individuals initially identified, we added 1,332 for a minimum of 2,010 individuals exhumed in 273 sites. The location is known for 902 of 934 Euro-Canadians (97%), 625 of 912 Ancestors (68%), and 61 of 164 unknown (37%).

By updating this database we learned that Ancestors were exhumed and stored at various institutions much more often than Euro-Canadians. An overwhelming majority of Ancestors’ locations remain unknown. Some need further investigation, because they were relocated (sometimes outside of Quebec) or lost. Much work remains to update the database acquired from the MCC, because information is still missing. Our results reveal an unbalanced management protocol in terms of access and care between Euro-Canadian human remains and those of Indigenous origin. Figure 2 shows three major peaks of archaeological intervention on Indigenous sites: the first between 1960 and 1969 (n = 44), the second between 1980 and 1989 (n = 48), and the last one between 1990 and 1999 (n = 41).

Figure 2. Histogram of potential origin for 345 reports of archaeological excavations in Quebec by years of excavations. The chronological periods are divided into 10-year periods starting in 1940; all reports prior to that date were grouped together.

History of Heritage Management and Bioarchaeological Practices in Quebec

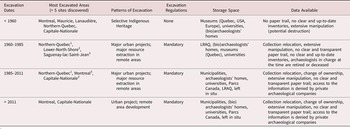

In this section, we present the trajectory of both heritage and bioarchaeological practice in Quebec over the past 60 years, which shows that human remains management can be directly linked to the excavation date (see Table 1; Figure 2). Some findings from our database and obstacles encountered while attempting to obtain information from various institutions are included to show how past practices continue to affect the current state of bioarchaeological practice.

Table 1. Key Findings Regarding Locations of Archaeological Human Remains in Quebec, ordered by Excavation Period.

1more than 50 sites 2more than 20 sites 3more than 10 sites

Before 1960: The Legacy Collections

Prior to 1960, physical anthropologists studied archaeological human remains for the purpose of establishing a hierarchy between populations from a zoological perspective and to prove the superiority of European populations (Caspari Reference Caspari2003). During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most European and American museums were founded to house objects collected all over the world, especially in colonized territories. As a result, centuries of large-scale archaeological discoveries are now scattered throughout the globe without the knowledge of Indigenous communities. The term “legacy collection,” which is borrowed from Meloche and Spake (Reference Meloche and Spake2019), clearly characterizes collections with unclear provenance because of poor or nonexistent documentation. Many legacy collections were “entrusted” to museums, but as administrators, filing systems, and internal policies changed over time, they were forgotten or misplaced (Colwell Reference Colwell2021; Meloche and Spake Reference Meloche and Spake2019; Redman Reference Redman2016). Generally, legacy collections of Ancestors are not systematically managed in a very transparent way.

During our exchanges, two museums (B and C) that we contacted repeatedly stated that they always acted in “good faith” toward Indigenous communities, but these exchanges mainly served to reflect this problematic past. Our discussions confirmed that the lack of regular cataloguing may indicate that the collections contain a higher number of individuals than reported. Even though our requests to museum B raised questions that they were uncomfortable with, we were able to quickly gather useful information via email. Things were more complicated with museum C: after receiving our inquiries, they let things drag on by stalling or asking for more details. Museum C only shared information that was already available and raised confidentiality concerns on sensitive data that were already published. During our visit to one of their storage locations, the museum staff restricted our access exclusively to the collections that we had inquired about based on their prior—and incomplete—cataloguing under curators’ supervision. There may be many more archaeological human remains in museums from this period, but poor documentation and the absence of recent records make them virtually impossible to find.

Between 1960 and 1985: Nationalization and Centralized Regulations

The Quiet Revolution of the 1960s describes how the Quebec government moved toward modernity and nationalization (Chaplier Reference Chaplier2006; Otis Reference Otis2019). In 1961, the MAC was created to build a francophone national identity and counter dominant anglophone politics (Breton Reference Breton1988; Lamont and Bail Reference Lamont and Bail2005). Urban expansion in large cities and resource extraction projects in remote areas became Quebec's main driving economic force. Quebecois CRM archaeology developed to document and protect archaeological heritage from land development. The Société d'archéologie préhistorique du Québec (Prehistoric Archaeological Society) was created in 1969, and the site of Pointe-du-Buisson was the first one to provide documentation on Ancestors (Desrosiers and Lapointe Reference Desrosiers and Lapointe1999). In 1972, the Cultural Property Act legally protected and promoted the most “representative” historical documentation, objects, archaeological sites, building, or places related to Quebec's national heritage (Dumont Reference Dumont and Dumont1993). The MAC managed and stored both public and (some) private collections from all over Quebec at the Laboratoire et Réserve d'archéologie du Québec (LRAQ). Most development projects where bioarchaeological excavations took place occurred on Indigenous ancestral lands without their consent.

Between 1960 and 1985, archaeological human remains were mainly housed at the then renamed MCC and Parcs Canada's official heritage building (LRAQ and the Museum of Canadian History, formerly the Canadian Museum of Civilization / National Museum of Man). Since 1972, LRAQ has loaned human remains to bioarchaeologists so that they could analyze Ancestors in their laboratories, at universities, or sometimes at home. We contacted museums, universities, and institutions in Quebec and elsewhere to inquire about their collections of human remains (Supplemental Text 1). We failed to obtain more information from universities B and C, but at university A, we succeeded in finding previously missing boxes of human remains and matching other missing ones with some “unknown collections” stored at other places. Nevertheless, many archaeological human remains collected during this period are still considered “potentially lost.” Between 1965 and the mid-1980s, there was no systematic tracking of the status of these loans, and we hypothesize that researchers may not have returned the entire collection of human remains loaned to them. Therefore, it is not surprising that collections belonging to at least six sites were found at different locations; one of them was only partially reburied (Martin-Moya Reference Martin-Moya2022).

Although archaeological excavations were regulated, bioarchaeological analyses were not: unclear paper trails and questionable management issues have made the task of repatriation and rematriation very complex. Many Ancestors are kept temporarily at LRAQ until the MCC initiates those processes, which tend to proceed very slowly (MCC, personal communication 2022). In addition, the MCC and some museums and universities often explicitly claimed they were unable to assess whether contemporary Indigenous communities are affiliated with past ones based on archaeological data. This is especially the case for sites where many communities used to gather for events such as collective funeral rituals and trade fairs.

Between 1985 and 2011: Power Is Transferred to Municipalities

The 1985 update of the Cultural Property Act stated that most of the MCC's responsibilities regarding heritage management were to be transferred to municipalities (MCC 2012). Consequently, if no municipal regulation stipulated that archaeological work should be carried out prior to any development project, potential archaeological sites were left unprotected. Some cities, such as the City of Montreal and Quebec City, did develop their own heritage management strategies. The number of archaeological firms also increased in the early 1990s (Desrosiers and Lapointe Reference Desrosiers and Lapointe1999) as major extraction projects in remote areas were conducted (e.g., Létourneau et al. Reference Létourneau2013; Hayeur Reference Hayeur2001). The privatized framework used for CRM archaeology in northern Quebec was extended to the whole province, applying also to municipal management of the land. Two instances of malpractice regarding human remains management were reported in Quebec: the destruction of an Irish cemetery to accommodate urban development with no opposition from archaeologists (Larocque Reference Larocque1993:3) and a private construction company's removal and partial destruction of the archaeological context of an Indigenous ancient burial without consent of the communities (Larocque Reference Larocque1997: 7). This lack of regulation spurred bioarchaeologists to urge the federal government and municipalities to strengthen heritage management.

In 2000, Parcs Canada developed guidelines to manage and store archaeological human remains. And in 2001 the Bio-Archéologie et Enquêtes judiciaires (Bio-Archaeology and Forensic Investigation) (Gagné and Clermont Reference Gagné and Clermont2002) conference was held to produce the first written guidelines of conduct for bioarchaeological excavations in Quebec. Even though the Cultural Heritage Act of 2011 stipulated that archaeological work must be carried out before any development project is begun, the conference proceedings of 2001 remain the only “formal” regulations in Quebec on how to excavate and analyze archaeological human remains. However, recent problems with the mistreatment of archaeological human remains in Quebec City, such as the discarding of well-preserved brains, show that formal regulations cannot replace legal enforcement (Baillargeon Reference Baillargeon2020; Lessard Reference Lessard2021; Rémillard Reference Rémillard2020).

From 2000 onward, archaeological human remains were no longer being curated and stored at LRAQ; these responsibilities were delegated to contractors, such as Hydro-Quebec, municipalities, and dioceses. These contractors had to supply a space that met specific standards (e.g., temperature, humidity) to enable bioarchaeological analysis, or they had to provide a long-term storage solution if the remains were not immediately reburied. Universities and main urban cities like Quebec and Montreal have their own archaeological storage space. Contractors who may not have the adequate space, means, or time usually hire a professional archaeologist or a private archaeological company to analyze and store the remains. Most professionals do not have short-term storage space, and in the absence of clear regulations, some store collections at home.

The fragmentation of the archaeological collections into different locations exacerbates problems caused by the absence of regulations for exhuming and managing archaeological human remains. Because municipalities now have the responsibility of heritage management, they can regulate archaeological discoveries on lands under their jurisdiction as they please. If they decide to move, loan, or rebury Ancestors, they do not have to formally consult with any community or stakeholder, which increases the risks of these remains getting lost or divided. We could easily locate all Euro-Canadian remains because most were still stored or reburied by dioceses. This was not the case for most of the Ancestors. For five archaeological sites in city A, their curators told us that no burials and human skeletal remains were found during excavations, even although the ISAQ database indicated otherwise. Moreover, for one site, its previous curator confirmed that Ancestors were found and that all the boxes were moved to city A. A visit to their archaeological storage area could help sort out this issue.

From 2011 to the Present

Due to the increasingly decentralized management of human remains from the 1980s onward, municipalities and private archaeological companies hold most of the information concerning those collections. More than 90% of the archaeological excavations in Quebec are carried out by private companies. This fragmentation of archaeological excavations, lack of regulation, and unstandardized archaeological methodologies make it difficult to access information on Ancestors (Kolhatkar et al. Reference Kolhatkar, Trudel-Lopez, Rousselle, Gervais and Gagné2020; Zorzin Reference Zorzin2011; Zorzin and Gates St.-Pierre Reference Zorzin and St.-Pierre2017). This hinders our ability to build a database in three ways. First, private companies often do not want to share information that could affect their relationship with present or potential contractors. Second, we hypothesized that Ancestors are often left in situ, untouched and unrecorded by CRM archaeologists. This strategy allows companies to avoid sensitive issues related to Indigenous communities, although this hypothesis would need to be confirmed. Third, from 2011 onward, little information is available (no reports were added to the MCC's database since 2018), and our database remains incomplete (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure 1). According to experts from the Huron-Wendat Nation, the new amendment to the Cultural Heritage Act still neglects Indigenous history and the Ancestors in order to better protect Quebecois heritage buildings (Rémillard Reference Rémillard2020).

Further Obstacles to Building a Database

To find potential storage locations and the Ancestors, one first needs to identify the potential owner based on the date of excavation and the way the collection was managed (Table 1). However, Indigenous communities must overcome an additional set of obstacles simply to build an Ancestors’ database: navigating concerns about repatriation and rematriation that Canadian institutions regularly raised when answering our queries. These concerns feed the following argument. First, Canadian institutions cannot assess which Indigenous community is more legitimate because of insufficient archaeological data. This justifies limited access to storage rooms and retaining the remains of Ancestors out of respect for other communities. Second, Ancestors can only be repatriated or rematriated under certain conditions dictated by the institutions. Finally, good faith is used to muddle collaborations between archaeologists and Indigenous communities, and to disengage Canadian institutions from decision-making. All the authors of this article have been involved in such processes.

Scientific Objectivity versus Indigenous Knowledge

The ability to settle a repatriation or rematriation issue rests with non-Indigenous archaeologists and Canadian institutions that promote scientific expertise over Indigenous knowledge. Within this framework, they consider themselves to be in a better position than Indigenous communities to make decisions about Ancestors’ fates. The practice and transmission of the past thus rely on non-Indigenous archaeologists. Indigenous communities (except some Indigenous archaeologists) are not invited to participate on this issue. Archaeologists have argued that Indigenous communities tend to instrumentalize archaeological discoveries to facilitate their political objectives or to provoke conflicts with other groups over land ownership (Marceau Reference Marceau2020). Only scientific communities seem to have the objective knowledge to do so. A cultural-historical archaeology approach dismisses ancestral knowledge and oral traditions as having no scientific value and favors material cultural remains (Meloche et al. Reference Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020; Nicholas Reference Nicholas2008, Reference Nicholas, Phillips and Allen2010, Reference Nicholas2021; Wonderley and Sempowski Reference Wonderley and Sempowski2019). A Western archaeological approach relying on “scientific objectivity” does not help understand the past and has mostly served to divide past and present populations by claiming that current populations are not biologically related to those of the past—as in the case of the Ancient One (also known as Kennewick Man; Kakaliouras Reference Hutchings and La Salle2019), or of the Iroquoians of the St. Lawrence Valley (Wonderley and Sempowski Reference Wonderley and Sempowski2019). Indigenous groups are often presented as static.

As a result, many unidentifiable human remains are stuck in a bureaucratic dead-end because empirical archaeological data do not allow the attribution of a legitimate descent (Atalay and Shannon Reference Atalay and Shannon2019). Communities must use fact-based criteria from cultural-history theory—and, increasingly, genetics—to demonstrate that they are the legitimate descendants of precontact populations. Those practices are deeply rooted in a colonial approach to history and undermine the ability of Indigenous people to manage their own affairs (Manuel and Derrickson Reference Manuel and Derrickson2018; Nicholas Reference Nicholas2021; Widdowson and Howard Reference Widdowson and Howard2008). If archaeological finds cannot build a consensus between Canadian institutions and Indigenous communities, Ancestors remain out of their graves.

Choice Is Constrained Upstream from Decision-Making

Even when archaeological finds and other criteria deemed objective do serve to build a consensus between Indigenous communities and Canadian institutions, this process still happens within a colonial framework that has been built unilaterally. Indeed, Indigenous communities must rely on Canadian institutions’ transparency and willingness to return Ancestors and associated goods on a case-by-case and next-of-kin affiliation scenario (Hanna Reference Hanna2005; Meloche Reference Meloche2014; Meloche and Spake Reference Meloche and Spake2019; Pfeiffer and Lesage Reference Pfeiffer and Lesage2014; Seidemann Reference Seidemann2004 Reference Seidemann2020; Whittam Reference Whittam2015). Although institutions may base their decisions on a set of objective criteria—archaeological findings, available historical data, geographic proximity (e.g., management territorial units)—these criteria are not explicitly stated unless requested. As we have seen, these objective criteria eschew Indigenous knowledge.

For example, in the case of Parcs Canada, scientific discoveries and geographic proximity to the burials are used primarily to assess next-of-kin affiliation and thereby repatriation. Indigenous communities are involved in the repatriation and rematriation processes only when Parcs Canada has concluded that they were affiliated to the Ancestors’ remains in storage. Indigenous communities are then invited to the consultation table to discuss where their Ancestors should be buried (Parcs Canada, personal communication 2022).

Parcs Canada repatriation processes show the limits of FPIC procedures. Because the FPIC process relies on “objective” (archaeological) data and only seeks to inform and not include Indigenous communities at this stage, a community's involvement remains limited; insufficient archaeological data might exclude other legitimate Indigenous communities from the consultation table. In addition, Indigenous communities tend to agree on the final burial location, because they consider it more important to rebury Ancestors than to initiate territorial claims, which are often feared by institutions (Parcs Canada, personal communication 2022). They certainly do not need a Canadian institution to tell them where to bury them. Yet, if Indigenous communities do not accept the repatriation and rematriation framework's terms and do not engage in such processes, Ancestors remain out of their graves.

Acting in Good Faith

Mitigation policy “in good faith” is at the heart of the colonial strategy toward Indigenous communities (Cortez et al. Reference Cortez, Bolnick, Nicholas, Bardill and Colwell2021). Yet this policy has an inherent contradiction with which Indigenous communities must work. On the one hand, bioarchaeologists have to show good faith, in the moral sense, while conducting the project. They must guarantee that this database will not be used to improve their professional careers when the location of the Ancestors is revealed. On the other hand, good faith is used as a tool by Canadian institutions to define repatriation and rematriation procedures unilaterally. Institutions frame this good faith as protecting Indigenous communities from any wrongdoing by non-Indigenous archaeologists and as taking care of their Ancestors.

For example, one of the museums claimed to one of the MCK authors that a bioarchaeologist had acted in bad faith during the project. An email written in French to an English speaker was provided as “proof” that the bioarchaeologists had a hidden agenda; the email contained a request made a year earlier to find out whether this museum housed Ancestors’ remains that could be used in research. The museum tried to show that it was sincerely trying to protect Indigenous communities from bioarchaeological harm. This attempt did not have the desired effect. Centuries of manipulation and failure to keep their promises have resulted in the MCK seeing neither Canadian institutions nor (bio)archaeologists as honest. Collaboration with non-Indigenous institutions and (bio)archaeologists is not based on personal virtue. The MCK author contacted the bioarchaeologists to clarify the issue.

This case shows how non-Indigenous heritage professionals and archaeologists see acting in bad faith as a common practice. This belief justifies their lack of action and their protection of the status quo. But this case also helped clarify what a reciprocal relationship might look like. This relationship should not be built on an assumption of good faith or any personal virtue but must be contractually agreed on and regularly updated at each stage of a project's progress. Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups need to proceed on the same front and at the same pace to help each other move forward when one party might get stalled by institutional obstacles that prevent Ancestors from returning to their graves.

Toward Mutually Beneficial Bioarchaeological Practices

The obstacles encountered while building the database and filing claims also point to a way forward. A reciprocity-based archaeology between non-Indigenous archaeologists and Indigenous communities is urgently needed to address these problems.

We believe that drawing on the concept of reciprocity put forth by Indigenous scholars (Atalay Reference Atalay2012; Atalay and Shannon Reference Atalay and Shannon2019; Simpson Reference Simpson2017) is key to grounding relationships between bioarchaeologists and Indigenous communities in equality and respect, which current practices sorely lack, and to reshaping a bioarchaeological practice free of its colonial legacy. Reciprocity is based on the idea that multiple parties have mutual obligations to one another, which cannot be fulfilled if one party has the upper hand and the power to decide unilaterally to concede to or deny a request made by the other. In the context of bioarchaeological practice, reciprocity means considering Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties on an equal level and how all may work together toward a common goal through the various means at their disposal; in this case, non-Indigenous scholars should give back the rights that they have granted themselves to decide, share, learn, and care for Ancestors. Renouncing these rights does not mean the end of scientific research. We only need to take a step back and think together about what is entailed in the excavation and analysis of archaeological human remains and Ancestors.

Various projects already use this reciprocal approach and should be seen as models for guiding bioarchaeologists, Indigenous communities, and governments engaging in land development procedures, research, and repatriation and rematriation processes. In the United States, recent amendments to NAGPRA dealing with unidentifiable human remains give more authority to local Indigenous and non-Indigenous teams and ensure that museums will rely not only on scientific discoveries but also on Indigenous knowledge through consultations (Atalay and Shannon Reference Atalay and Shannon2019; Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al. Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Maxson and Powell2011; Seidemann Reference Seidemann2020). Huliauapa'a (https://www.huliauapaa.org)—a nonprofit organization of Indigenous and non-Indigenous partnerships—helps students and professionals lead ethical projects to preserve and protect Native Hawaiian histories. Carrying Our Ancestors Home (https://coah-repat.com/browse/media-type/file), a collaborative initiative created at the University of California at Los Angeles by Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals—NAGPRA officials, bioarchaeologist researchers, and students—educates and supports various authorities on repatriation and research issues.

A third example can be found in the case we presented here. Our mutual experience reflects how the MCK built a reciprocal relationship with bioarchaeologists from the University of Montreal that ended up being beneficial to both parties. On the one hand, without the MCK, we bioarchaeologists would never have engaged with those questions even though we in theory supported the decolonization process. As bioarchaeologists, we knew that we needed to modify our practices because our methods were not in line with Mohawk values regarding the people we “studied,” but we did not really know where to start. On the other hand, we had the capacity to access and navigate as non-Indigenous scholars through various Canadian institutions to build up an Ancestors’ database. Through this partnership, we (bioarchaeologists and Mohawks) were thus able to draw from our different experiences as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

To develop this reciprocal relationship, both sides need to reach a consensus on some difficult issues. Indigenous communities might not be comfortable with involving non-Indigenous researchers or professionals because of their past negative experiences. Many archaeologists, bioarchaeologists, and anthropologists took every opportunity to collect unique data because their goal was to improve scientific knowledge or their own careers, but they failed to consider the needs and values of Indigenous communities. The relation between bioarchaeology and colonialism gave birth to intense debates where key issues were raised regarding the discipline's past role in facilitating the colonial project and methodological approaches’ impact on limiting Indigenous involvement. New bioarchaeological approaches that create and improve massive databases are further limiting the involvement of Indigenous communities, because they must keep up with new technologies and methodologies that proceed at a much quicker pace than legal and ethical frameworks (Kukutai and Taylor Reference Kukutai and Taylor2016; Supernant Reference Supernant, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020). Bioarchaeologists tend to confuse “enhanced” methods of data acquisition with ethical and inclusive practices. Indigenous communities are entitled to wonder whether these methods are really for their benefit or are being used to gain access to sensitive and sensational information that could be profitable to non-Indigenous bioarchaeologists’ careers (Austen Reference Austen2021).

Indigenous heritage and repatriation issues helped bioarchaeologists reconsider the relationship between Indigenous rights and what can be learned from studying Ancestors (Kakaliouras Reference Kakaliouras2008, Reference Kakaliouras2014; Supernant Reference Supernant, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020). Long-term discrimination has minimized Indigenous involvement in bioarchaeological practices and repatriation and rematriation issues (Dekker Reference Dekker2018; Hutchings and La Salle Reference Hutchings and La Salle2018, Reference Hutchings and La Salle2019; Kakaliouras Reference Kakaliouras2012; Nicholas and Bannister Reference Nicholas and Bannister2004). Recently, new narratives around “decolonization” and “reconciliation” practices have been promoted, and efforts have been made to look for less invasive methods to prevent the potential loss of scientific data (e.g., 3D imaging, ancient DNA, isotopic studies; see Cortez et al. Reference Cortez, Bolnick, Nicholas, Bardill and Colwell2021; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Blair and Nicholas2020; Kukutai and Taylor Reference Kukutai and Taylor2016; Supernant Reference Supernant, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020). If archaeological excavation cannot be avoided, bioarchaeologists should help existing local cultural centers involve the local population in archaeological practices and their Indigenous heritage; for example, by sampling, collecting, analyzing, and disseminating data. They could work from the guidelines presented earlier while adapting them to local needs and sensibilities (Cortez et al. Reference Cortez, Bolnick, Nicholas, Bardill and Colwell2021; Spake et al. Reference Spake, Nicholas, Cardoso, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020; Supernant Reference Supernant, Meloche, Spake and Nichols2020). As the Huliauapa'a project shows, the goal is not to stop all bioarchaeological projects but to develop ethical projects that use respectful and reciprocal methodologies to investigate the past.

Once these issues have been clarified, the fact remains that the US and Canadian governments use their NAGPRA and “good-faith” policies to retain authority over whether institutions should comply or not with repatriation and rematriation demands (Atalay and Shannon Reference Atalay and Shannon2019; Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al. Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Maxson and Powell2011). The reciprocal relationship that archaeologists and Indigenous communities have managed to build around specific projects needs to be expanded to a larger scale (Atalay Reference Atalay and Shannon2019; La Salle Reference La Salle2010). Reciprocity-based archaeology cannot be successful if it is only based on isolated projects; it needs to permeate the broader institutions that shape today's (bio)archaeological practices. A good start would be to build a nongovernmental association comprising Indigenous communities, (bio)archaeologists, and representatives of the public to tackle four urgent issues: (1) revise the consultation process prior to any archaeological excavation; (2) systematically map all Ancestors’ locations and archaeological collections to facilitate repatriation and rematriation processes; (3) build a storage space dedicated to Ancestors’ care that is managed by Indigenous communities according on legal guidelines on how to document, exhume, and care for these individuals; and (4) rebuild mutual trust between archaeologists and Indigenous communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank Christian Gates St.-Pierre for his advice and help in building the project. We also thank Adrian Burke and Pierre Desrosiers for commenting on and editing previous versions of this article and thank the three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version. We finally thank the various institutions, museums, and universities that were contacted for this project.

Funding Statement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Groupe de recherche As2 ArchéoScience/ArchéoSociale (FQRSC).

Data Availability Statement

The final database and all information concerning archaeological human remains found during this research are under the supervision of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake. Because of its sensitive content, the database is not publicly available. For more information on the database, contact the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake.

Competing Interests

Diane Martin-Moya received a grant from Groupe de recherche As2 ArchéoScience/ArchéoSociale (FQRSC) to build the database. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2023.38.

Supplemental Text 1. Summary of the Requests for Information from Various Institutions and Their Results.

Supplemental Figure 1. Histogram of Potential Locations per Years of Archaeological Excavation for 345 Reports.