But I kept thinking: If only I could just, you know, find myself in a quick but violent accident. Academic failure felt like the death of a substantial part of my identity—and I sincerely believed the best possible outcome was for the rest of me to die along with it. (Schuman, Reference Schuman2014).

In this article, we address the phenomenon of academic failure, focusing in particular on the emotions and consequences that flow to employees from ‘deviation from expected and desired results’ (Cannon & Edmondson, Reference Cannon and Edmondson2001: 162). These authors go on to note that ‘[Failure] includes both avoidable errors and unavoidable negative outcomes of experiments and risk-taking. It also includes interpersonal failures such as misunderstanding and conflict.’ Although all employees encounter failures at some point in their working lives, we suggest that academics are especially vulnerable in that they receive critical feedback and scrutiny of their work from many different sources on a regular basis, which in turn can trigger negative emotional responses. Common examples include rejections of applications for funding, poor teaching evaluations, negative feedback from students, unsuccessful promotion applications, rejection letters from journal editors, unsuccessful research outcomes and failure to achieve job security through a tenured appointment.Footnote 1

Given the competitive, demanding culture found in many universities (Fischer, Ritchie, & Hanspach, Reference Fischer, Ritchie and Hanspach2012), the nature of the work itself, and the individual characteristics required for success (see Araújo, Cruz, & Almeida, Reference Araújo, Cruz and Almeida2017), we suggest that those of us who work in academia are especially likely to encounter failure in our careers, and may therefore be vulnerable to its potentially damaging consequences. For many academics, rejection of manuscripts in particular can represent a significant threat to their identity (see Day, Reference Day2011), meaning that it can be particularly painful. Currently, anecdotal evidence (e.g., see Clark & Sousa, Reference Clark and Sousa2015) suggests that failure is a common experience in academia and, as we discuss later, the stress associated with failure (and potential failure) can have personal, health, economic, and ethical implications for employees. Given its prevalence and importance, we argue that academic failure is clearly a topic deserving of more attention and discussion than it is currently receiving. The purpose of this essay, therefore, is to explore the phenomenon of failure and its associated emotions in academia. To achieve this aim, we adopt Ashkanasy’s (Reference Ashkanasy2003) multilevel model to illustrate how failure can occur at multiple levels of analysis in academic settings, and consider its consequences for employees.

Before going further, it is important first to acknowledge that failure is a complex phenomenon (cf. Cannon & Edmondson, Reference Cannon and Edmondson2001). It can be both explicitly and implicitly defined in work settings and unspoken beliefs about failure, while perhaps not openly acknowledged, can have also a profound impact on employees’ well-being. As Kajitani and Bryant (Reference Kajitani and Bryant2005) observe, a tenured full professorship is regarded as the epitome of success in academic life, and PhD students (i.e., aspiring academics) who do not achieve this goal (or pursue a nonacademic career) are often considered ‘failures’.

Additionally, as academics progress through their career hierarchy, failure becomes progressively more inevitable (Marx, Reference Marx1990), and their personal conceptualisations of failure change concomitantly. For example, how individuals define failure as a graduate is unlikely to be the same as how they define failure as an early career academic, or as a tenured, seasoned faculty member. Also, and as we discuss later, failure is not inherently a negative experience: how individuals frame episodes of failure is critical in determining their career and personal outcome.

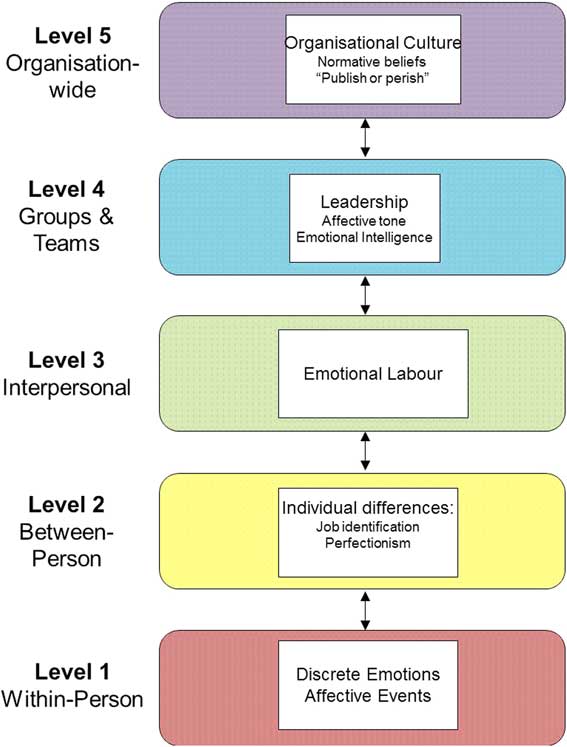

We structure our essay as follows. We begin with a brief review of what we know about failure in organisational settings. There is a rich research base here and we suggest that how we learn from failure in organisations can help us to understand academic failure in more depth, including ways that it can be effectively managed. Next, drawing on Ashkanasy’s (Reference Ashkanasy2003; see also Ashkanasy & Dorris, Reference Ashkanasy and Dorris2017) five-level model of emotions in organisations, we discuss how failure can occur and trigger emotional responses at five levels in academic settings: within-person, between-persons, interpersonal interactions, groups and teams (and leadership), and organisation-wide. We also suggest that the culture (and in turn accepted normative beliefs) in academia, the challenging nature of the work itself and individual characteristics can collectively create multiple opportunities for failure and a low tolerance for failure in academic settings, which can lead to negative emotional experiences.

We also consider how these factors can contribute to the high rates of mental illness in academia. In this regard, while this is an issue that has been widely discussed in the media (e.g., Anonymous, 2014; Shaw & Ward, Reference Shaw and Ward2014; Shaw, Reference Shaw2014; Else, Reference Else2017), it has to date received only limited attention in the scholarly literature. We discuss further how pressures facing contemporary academics – and in turn fear of failure – can encourage them to engage in unethical practices, such as fabrication of data and plagiarism (Butler & Spoelstra, Reference Butler and Spoelstra2015). Next, we consider how we can effectively prepare our doctoral students and early career academics for the reality that failure is an inevitable part of academic life and build resiliency in the next generation of scholars. Finally, we highlight some key areas and important issues for investigation in future research.

FAILURE AND LEARNING FROM FAILURE IN ORGANISATIONAL CONTEXTS

It is axiomatic that all employees inevitably encounter failure at some point in their working lives. Organisations, too, encounter crises, mishaps, and damaging incidents throughout their life cycle, and must learn from failure to innovate and remain competitive (Edmondson, Reference Edmondson2011). There is moreover considerable evidence that multiple factors contribute to organisational failures, including environmental factors, such as natural disasters and new global competition; a lack of adequate resources; and inaccurate managerial perceptions, inactions and poor decision-making (for a review, see Amankwah-Amoah, 2016). At an individual level, Edmondson (Reference Edmondson2011) suggests that employees can fail at work for a wide variety of reasons, and that failures generally fall into three categories: (1) preventable, (2) complexity-related, and (3) ‘intelligent’. While failures attributed to deviance and inattention, for example, should rightly attract blame and punishment, Edmondson cautions that organisations should acknowledge and reward ‘intelligent failures’. These kinds of failures occur through essential experimentation and ‘provide valuable new knowledge that can help an organisation leap ahead of the competition and ensure its future growth’ (p. 51). We argue that this kind of failure should be encouraged in academia, especially when working with graduate students and early career academics.

Much of the research into failure (e.g., see Cannon & Edmondson, Reference Cannon and Edmondson2005) has tended to focus on barriers to organisational learning from failure, which include those embedded in technical and social systems, and how these barriers can be addressed. Technical barriers include a lack of knowledge about how to analyse and to understand failure experiences, as well as challenging task designs and complex systems. From a social perspective, Cannon and Edmondson note that human beings are also inherently reluctant to acknowledge their failures, disappointments, and misadventures – largely because of the fear of shame and embarrassment among important others.

The desire to be seen as capable and competent is especially important in the workplace, where successes are typically rewarded and failures punished (Cannon & Edmondson, Reference Cannon and Edmondson2005). We suggest that this belief is especially relevant in academic contexts, which are typically characterised by high levels of competition and scarcity of jobs for new graduates (McKenna, Reference McKenna2016). These same social processes can also lead organisations to discourage their employees to learn from failure. Cannon and Edmondson note for example that managers often lack the interpersonal skills to encourage constructive discussions following failure, meaning that employees may feel embarrassed or blamed for mishaps, and the failure itself may not be discussed at all.

How, then, can these barriers be overcome? Cannon and Edmondson (Reference Cannon and Edmondson2005) propose that learning from failure is a complex process, and that managers can facilitate this through three critical activities: (1) identifying failure, (2) analysing failure, and (3) engaging in deliberate experimentation. These authors also emphasise the importance of reframing failure and, in doing so, the need for employees to acknowledge the inevitability of failure in the workplace.

Other authors have investigated the notion that organisations, and indeed leaders, can build their tolerance for failure through engaging in specific practices. For example, Farson and Keyes (Reference Farson and Keyes2002) argued that ‘failure tolerant leaders’ are critical to encouraging innovation and success in organisational settings. Farson and Keyes define such leaders as ‘executives who, through their words and actions, help people (to) overcome their fear of failure and, in the process, create a culture of intelligent risk taking that leads to sustained innovation’ (Reference Farson and Keyes2002: 66). These behaviours include genuinely engaging with employees, freely admitting their own errors, creating a culture of collaboration rather than competition, and encouraging sharing of ideas and suggestions for improvement. Clearly, greater openness in discussing mistakes, mishaps, and disappointments in academia – and acknowledging our own and others’ vulnerability – is an important first step in changing the direction of the conversation.

In sum, the extant research into failure tells us that a myriad of factors can lead to failures in work settings, and that organisations should ultimately encourage ‘intelligent failures’ (i.e., failures that lead to improvements and greater knowledge). There is also evidence that organisational leaders can take steps to facilitate effective learning from failure.

In the next section of this article, we apply Ashkanasy’s (Reference Ashkanasy2003) multilevel model to explain how emotions following failure can occur at multiple levels of analysis in academic settings. Although we focus mainly on the negative emotions that typically follow failure, such as hurt, anger, and shame (Gino & Staats, Reference Gino and Staats2015), we also acknowledge that failure can lead to positive emotions, such as pride, depending on how it is perceived. Following this, we discuss how we can begin to normalise failure in academia and build a culture of resiliency.

FAILURE IN ACADEMIA: A MULTILEVEL MODEL

Before discussing the nature of failure in academic settings, we believe that it is important to recognise that academia is a unique profession in many ways. While some scholars enter academic life immediately following their doctoral studies, others choose to pursue an academic career after working in industry, sometimes for a considerable period of time (Lindholm, Reference Lindholm2004). Many academics combine teaching, research, and consulting work and in doing so pursue multiple passions. For example, one of the authors of the article began his academic career after working for 18 years as a water resources engineer; he decided to pursue an alternative career in academia after realising that this would offer him the opportunity to explore in depth a key area of personal interest, namely the nature of effects of human behaviour in organisations.

In fact, it is not surprising that many individuals view academia as an attractive career option (see Bartram et al., Reference Bauer and Spector2017). Tregoning (Reference Tregoning2016) recently discussed some of the advantages of an academic career in an (initially anonymous) article for The Guardian: these include the opportunity to build global networks with like-minded colleagues, doing work that has societal value, the opportunity to build a research career that inspires passion and meaning, working with students, especially those whom we can mentor and support; and control over one’s working hours (to an extent). Vale (Reference Vale2010) similarly discussed the most enjoyable aspects of his career as an established (academic) scientist, emphasising the delight of discovery, pursuing new areas of research throughout a career, and contributing to a body of knowledge. An academic career, therefore, can be rich and fulfilling for many reasons.

At the same time, however, working in an academic role, especially from the point of view of a doctoral student or early career researcher, can be exceptionally stressful. In a thoughtful discussion, Di Pierro (Reference Di Pierro2017) reviewed evidence from studies into graduate students’ mental health, observing that the pressures of graduate school place students at risk of developing serious mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression. The suicide of one talented physics scholar (included in the acknowledgments of an academic paper) generated troubling questions about the nature of the postdoctoral system and how young academics are treated (Grant, Reference Grant2017). Smith (Reference Smith2017) argues further that the rise of adjunct or ‘clinical’ positions in the United States has created a class of poorly paid, highly educated employees who may never achieve an elusive tenure-track position. Concomitantly, Cannizzo and Osbaldiston (Reference Cannizzo and Osbaldiston2016) present the results of a survey of Australian academics, demonstrating that the nature of academic work in Australia is rapidly evolving with the emergence of similar difficulties to those encountered in the US context as junior academics struggle to establish a workable work–life balance.

In the following section, based on the Ashkanasy (Reference Ashkanasy2003) model, we seek to explain the role of emotions in this context, and integrate empirical and anecdotal evidence to build our argument. In Figure 1, we provide an overview of these effects across the five levels of analysis, and suggest how the levels are entwined and serve collectively to shape academics’ reactions to failure. At the first level, we use affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996) to explain how individuals’ emotional responses to failure can shape their attitudes and behaviour in academic settings, and consider the discrete emotions involved in the experience. At the next level, we explore some of the individual difference variables that may influence how academics respond to failure, focusing specifically on job identification and perfectionism. Following this, we turn our attention to the interpersonal level to suggest that experiencing failure at work can result in significant emotional labour, potentially leading to harmful consequences for academics. We then explore failure in the context of groups and teams, highlighting the critical role of leaders in building a failure-tolerant climate and managing responses to failure in academic settings. Finally, we argue that cultural norms and expectations in academia play a key role in how failures are perceived and addressed. We also emphasise that our discussion here is not exhaustive, and we hope that this article provides a starting point for future conversations and research in this area.

Figure 1 A five-level model of emotions and failure in academia (based on Ashkanasy, Reference Ashkanasy2003).

Level 1: Within-person

At the within-person level of analysis, Ashkanasy (Reference Ashkanasy2003) refers to affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss and Cropanzano1996), which holds that ‘affective events’ derived from the workplace environment result in two forms of behaviour. The first is ‘affect-driven’, where the employee’s positive (e.g., spontaneous helping) or negative behaviour (e.g., abusing a colleague) is a direct result of the affective experience. In the second, the accumulation of emotions resulting from these events over time can influence more stable work attitudes and result in ‘judgement-driven’ behaviours (e.g., working hard or quitting). The theory has since been extensively validated using a wide range of research methods (see Ashkanasy & Dorris, Reference Ashkanasy and Dorris2017 for a recent review).

Moreover, as a result of extensive research from a variety of different disciplines, including clinical psychology, social psychology, and neuropsychology, we have a good understanding of the different discrete emotions involved in the experience (and anticipation) of failure as an affective event. These include the so-called ‘basic’ emotions, such as anger and fear (Ekman, Reference Ekman1984, Reference Ekman1992), and ‘self-conscious emotions’ such as guilt, shame, embarrassment, and pride (Tangney & Fischer, Reference Tangney and Fischer1995; Lewis, Reference Lewis2008). As the term suggests, self-conscious emotions require self-awareness and appear to be especially important in the context of failure (Hareli, Shomrat, & Biger, Reference Hareli, Shomrat and Biger2005). In this regard, Tracy and Robins comment that, ‘people tend to experience self-conscious emotions, such as pride and shame, only when they become aware that they have lived up to, or failed to live up to, some actual or ideal self-representation’ (Reference Tracy and Robins2004: 105). Indeed, the literature on project failures suggests that individuals experience a complex range of negative emotions following an unsuccessful outcome, including disappointment, grief and fear (Shepherd, Patzelt, & Wolfe, Reference Shepherd, Patzelt and Wolfe2011).

To the best of our knowledge, academic understanding about the nature and immediate effect of emotions involved in failures in academic settings is still underdeveloped however. Anecdotal evidence suggests nonetheless that failures in academia are associated with negative affective events and experiences (e.g., Schuman, Reference Schuman2014; Diascro, Reference Diascro2016; Wang, Reference Wang2016), including anticipated emotions (i.e., emotions about future events), which lead to both affect- and judgement-driven behaviours.

In describing the academic job search experience, for example, blogger Jason Tebbe observed, ‘Every August and September, as I started getting ready and looking for the tenure-track job ads, I would get anxiety attacks and couldn’t sleep. Rejection exists in other fields but not to the point that it becomes a yearly ritual of self-hatred and emotional pain’ (Schuman, Reference Schuman2014). Another postdoctoral researcher and blogger, Michelle Newman (Reference Newman2017), recently described her struggle to find ongoing employment, noting that shame and guilt contributed to her feelings of inadequacy. Other individuals have also discussed the debilitating consequences of fear of failure, especially for PhD students, and how this can lead to imposter syndrome, self-sabotage and paralysis, further exacerbating their distress (e.g., Kajitani & Bryant, Reference Kajitani and Bryant2005; Mewburn, Reference Mewburn2010). We suggest that empirical studies exploring the antecedents and consequences of failure in academia represents an important avenue for future study.

This leads us to an important question: How do the emotions associated with failure (and anticipated failure) influence attitudes and behaviours in the context of organisations, including academic settings? At this level of analysis, we argue that affective events theory can help to explain how academics’ negative affective experiences can lead to outcomes such as emotional outbursts and/or reduced job satisfaction and organisational commitment resulting in decreased performance and increased turnover.

For example, in the case of a PhD student, multiple rejections of a manuscript or negative feedback from a supervisor may lead to feelings of anger, frustration, and despair, which in turn may lead to lower job satisfaction and affective commitment. As we have observed already, not all failures in academia will be perceived negatively and lead to distressing emotions. Our point is that, when failures are appraised negatively, and particularly when the appraisals involve self-blame and occur frequently over time, then this can negatively influence important work outcomes.

Of course, we also acknowledge that not all individuals will experience these unpleasant emotional responses to the same extent, if at all; as such, in our ensuing discussion we turn our attention to the role of individual differences in coping with failure in academic settings.

Level 2: Between-persons

While all academics will encounter failure to some degree in their working lives, not all will respond to the experience in the same way. Researchers investigating the role of individual differences in stress, coping, and resilience (e.g., Brougham, Zail, Mendoza, & Miller, Reference Brougham, Zail, Mendoza and Miller2009; Feder, Nestler, & Charney, Reference Feder, Nestler and Charney2009; Carver & Connor-Smith, Reference Carver and Connor-Smith2010; Bartley & Roesch, Reference Bartram, Gutting, Lyubomirsky, Kringelbach, O’Mara, Oswald and Revord2011; Holton, Barry, & Chaney, Reference Holton, Barry and Chaney2016) identify multiple factors that can influence how people will perceive and respond to stressful events, such as genetics, gender, personality traits, negative affectivity, and preferred coping styles and strategies.

For example, in a recent UK study exploring the relationship between specific individual traits and coping with stress in academia, Darabi, Macaskill, and Reidy (Reference Darabi, Macaskill and Reidy2017) found that academics with higher levels of self-efficacy, hope, gratitude, and optimism experience less stress in the workplace. In our discussion of the individual factors that may shape emotional and behavioural reactions to failure in academia, we focus on job identification and perfectionism.

Job identification

We suggest that one of the reasons that failure can be so painful in academic settings – and why certain individuals may struggle to manage the experience – is because many academics consider their work to be an extension of themselves. Peterson (Reference Peterson2017) recently provided an insightful critique of this phenomenon, arguing that PhD students in particular are especially vulnerable to equating their research with their identity. She further suggests that studying a topic that students genuinely care about can provide them with a sense of purpose, authenticity, and meaning; and this is exacerbated by sharing ideas and knowledge with others. At the same time, this intense identification can have a dark side. As Peterson notes in her blog post, ‘Over the five-plus years you spend as a graduate student, you begin to feel the subject matter is inherent to who you are. So the thing you get paid to research, teach and present is no longer just a professional identity but also foundational for your whole identity’. We suggest that the danger of this approach is that, when PhD students are faced with common failures in academia, such as nonsignificant research results, article rejections, or difficulty finding a job, they may be especially vulnerable to intense negative emotions and in turn struggle to cope.

Perfectionism

This is another individual difference variable that we propose is especially relevant to understanding emotional responses to failure in academic settings. As Siriwardena (Reference Siriwardena2013) observed, perfectionism is often seen a virtue in higher education settings, and has received considerable attention in discussions of academic life. Here, it is important to point out that researchers have identified different types of perfectionism. One particularly relevant form is labelled ‘self-oriented perfectionism’. This behaviour is characterised by excessive self-criticism, unrealistic expectations, and perceived pressure to reach unattainable standards. Perhaps unsurprisingly, maladaptive perfectionism is associated with negative outcomes such as low self-esteem, anxiety, rumination, and poor coping strategies (for a review, see Khatibi & Fouladchang, Reference Khatibi and Fouladchang2016). In our own personal experience, doctoral students and early career researchers seem to be especially vulnerable to succumbing to self-oriented perfectionism, often as a result of perceived expectations about performance.

Demonstration that self-oriented perfectionism is detrimental to performance and general well-being can also be found in a study by Sherry, Hewitt, Sherry, Flett, and Graham (Reference Sherry, Hewitt, Sherry, Flett and Graham2010). These authors found that self-oriented perfectionism in a sample of psychology professors is negatively related to a range of outcomes, including ‘total number of publications, number of first-authored publications, number of citations, and journal impact rating, even after controlling for competing predictors’ (p. 273).

Based in part on our own experiences and observations in academic settings, we suggest that self-oriented perfectionism can be paralysing and indeed may exacerbate any fear of failure. Additionally, we propose that self-oriented perfectionism may increase the likelihood that individuals will experience negative emotions following an episode of failure; this is because they will be more likely to interpret the experience as personally damaging and distressing. On a brighter note, it is heartening to observe (e.g., see Rockquemore, Reference Rockquemore2012; Siriwardena, Reference Siriwardena2013; Thorne, Reference Thorne2016; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016) that some scholars are beginning to acknowledge the toxic effects of maladaptive perfectionism in academic life, and we discuss ways to address such harmful beliefs at the end of this article.

Level 3: Interpersonal

The third level of the Ashkanasy (Reference Ashkanasy2003) model concerns perception and communication of emotions between individuals, for example, emotional labour. Sociologist Hochschild (Reference Hochschild1983) was the first to propose the term ‘emotional labour’ to describe the process of managing emotions and feelings at work in line with organisational expectations. Hochschild further proposed that individuals can engage in surface acting or deep acting. Researchers have explored the antecedents and consequences of emotional labour in numerous studies, and evidence indicates that surface acting is generally associated with negative work outcomes, including increased burnout and reduced job satisfaction (for a review, see Grandey & Gabriel, Reference Grandey and Gabriel2015). Subsequently Ashforth and Humphrey (Reference Ashforth and Humphrey1993) recognised the role of also displaying genuine emotions at work.

A small number of scholars (e.g., Krishnan & Kasinathan, Reference Krishnan and Kasinathan2017) have investigated emotional labour in the context of academic teaching and generally agree that it represents a significant issue in higher education. For example, Bellas (Reference Bellas1999) observed that teaching necessitates considerable emotional labour; lecturers are required to display appropriate emotions in front of their students in the classroom, which may be positive or negative, and sometimes they must keep their emotional responses neutral. Bellas (Reference Bellas1999) and later Hort, Barrett, and Fulop (Reference Hort, Barrett and Fulop2001) also noted the gendered nature of emotional labour in academia, such that women (who are generally employed in teaching and service roles) are required to engage in a higher degree of emotional labour than men. Zhang and Zhu (Reference Zhang and Zhu2008) also found teaching to be associated with significant emotional labour, and that surface acting was related to increased stress and burnout.

We proposed earlier in this essay that the experience of failure in higher education settings is frequently associated with negative emotions; at the same time, however, we know that academics are often expected to display positive emotions in the workplace, especially when interacting with students and senior staff (cf. Brotheridge & Grandey, Reference Brotheridge and Grandey2002). What happens, therefore, when an (inevitable) failure occurs? Based on the findings reported by Ogbonna and Harris (Reference Ogbonna and Harris2004), as well as our own personal experiences and observations, we argue that emotional labour, and particularly surface acting, is one way that academics learn to cope with and hide their distressing affective experiences following failure.

For example, an instructor may discover that a series of experiments has failed just before teaching a seminar; rather than acknowledging her or his frustration, the lecturer might choose to start the class with an apparently cheery demeanour, quite at odds with her or his feelings of disappointment. A graduate student may have a manuscript rejected, eliciting anxiety, distress, and disappointment, but feels the need to continue working on her or his thesis as if everything was alright. In one blog post, Feldman (Reference Feldman2015) argued that acknowledging negative emotions is largely discouraged in academia, and that silencing and suppression can lead to further distress. In her discussion of her experiences as a graduate student, she notes, ‘Academia requires that you conceal your feelings all the time, because, God forbid, someone (a professor, supervisor, administrator, colleague) be confronted with the fact that you’re a human being and you have feelings.’

We suggest that emotional labour, especially surface acting, can be particularly toxic following failure, and may be one reason for the high rates of mental illness and burnout in academic settings. As we have acknowledged already, however, individual differences will play a role in determining how people respond. In this respect, Tunguz (Reference Tunguz2016) investigated how tenure and gender influenced faculty exchanges with entitled students. In line with hypotheses, her results revealed that untenured academics engage in greater emotional labour than tenured academics in their interactions with students. She found further that, while tenure is associated with increased stress among female academics, tenure reduces the effects of emotional labour and stress among male academics. Given the dearth of research in this area, however, we agree with Hatzinikolakis and Crossman (Reference Hatzinikolakis and Crossman2010) that further empirical research is needed into emotional labour in business schools, and that it is especially important to explore its role in the context of failure.

Level 4: Groups and teams

At the fourth level of the model, Ashkanasy (Reference Ashkanasy2003) considers the role of emotions in groups and teams, including the role of leaders in shaping emotions in work settings. In academic settings, these leaders are the Deans and Heads/Chairs of Departments. These are therefore the people who influence the affective experiences of followers before, during, and after an episode of failure. It seems, however, that few researchers have to date explored the relationship between leadership and failures in higher education settings. This shortcoming clearly opens up multiple avenues for future investigation.

Rowley and Sherman (Reference Rowley and Sherman2003) observe that academic leaders must be able to manage a unique set of challenges. For example, leaders need frequently to make controversial decisions knowing that they may be disliked by their colleagues. Department Chairs are also often responsible for key administrative matters, such as hiring and firing faculty, organising class schedules, selecting the courses offered, and addressing student needs. Parrish (Reference Parrish2015) synthesised results from multiple studies in the higher education literature to develop the ‘Leadership Competency Framework,’ which consists of five specific behaviours that reflect effective academic leadership: (1) articulating a strong direction and vision; (2) encouraging a supportive and collegial work climate; (3) behaving with integrity, fairness, and consideration of others; (4) providing constructive feedback, and (5) promoting the interests of the department and institution to internal and external stakeholders. We suggest further that academic leaders are uniquely positioned to encourage their fellow academics to achieve key individual performance targets (e.g., a required number of publications each year), but at the same time they often feel that they are obliged ‘crack the whip’ if those targets are not met. Overall, it seems that academic leaders might struggle to practice these behaviours consistently while at the same time working in a complex and highly political organisational environment.

In line with the ‘affective revolution’ in the organisational sciences (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, Reference Bartley and Roesch2003), scholars now recognise that emotions and moods are a critical element of the leadership process (e.g., see Ashkanasy & Dorris, Reference Ashkanasy and Dorris2017). In the context of failure in academia, we suggest that leaders first help to set the ‘affective tone’ in groups (cf. George, Reference George1996) about risk-taking and the potential for failure. As we noted in the introduction to this essay, there are many opportunities to fail in academic settings, including in teaching, research, service, and industry engagement. Moreover, and as Farson and Keyes (Reference Farson and Keyes2002) have shown, failure-tolerant leaders engage with their followers at an individual level, reduce toxic competition between employees and ensure that failure is seen as an opportunity for learning and growth, rather than simply the opposite of success. When failures do occur, these leaders are able to distinguish between those that are normal and excusable, such a genuine mistake, and those that are the result of carelessness or inattention, and respond appropriately. Careful analysis of failures is critical to learning, and leaders play a key role in facilitating this process. Hackman and Wageman (Reference Hackman and Wageman2005) point out further that effective leadership following team failures is especially important – and leaders must be able to handle the emotional challenge of learning from the experience.

Cannon and Edmondson (Reference Cannon and Edmondson2005) argue in addition that many leaders simply do not have the skills or training to manage the ‘hot’ emotions involved in constructive discussion and scrutiny of their followers’ mistakes and errors. We suggest in this regard that the emotional intelligence (EI) of academic leaders may play an important role in managing these conversations, especially in groups, and helping their fellow academics learn from the experience. Although EI is still a topic of debate (e.g., see Antonakis, Ashkanasy, & Dasborough, Reference Antonakis, Ashkanasy and Dasborough2009), many scholars consider that it may contribute to effective leadership in work settings (e.g., Caruso, Mayer, & Salovey, Reference Caruso, Mayer and Salovey2002; Gardner & Stough, Reference Gardner and Stough2002; Dulewicz, Young, & Dulewicz, Reference Dulewicz, Young and Dulewicz2005; Rosete & Ciarrochi, Reference Rosete and Ciarrochi2005; Walter, Cole, & Humphrey, Reference Walter, Cole and Humphrey2011; Barbuto, Gottfredson, & Searle, Reference Barsade, Brief and Spataro2014).

In this regard, Parrish conducted a series of interviews with Australian academics focused specifically on the role of EI in academic leadership, and found that ‘traits related to empathy, inspiring and guiding others and responsibly managing oneself’ (Reference Parrish2015: p. 829) were identified as the most critical to effective leadership. Given that failure is such an emotionally charged process (Shepherd, Reference Shepherd2003), we propose that emotionally intelligent academic leaders should be better equipped to manage their followers’ emotions, to display empathy, and to manage their own emotions (e.g., frustration, disappointment, regret, etc.) following an episode of failure. On a related note, we propose that EI also likely plays an important role in managing failures in the research supervision process, and suggest that this represents an interesting area for future research.

Level 5: Organisation-wide

At the top level of the model, Ashkanasy (Reference Ashkanasy2003) turns his attention to how emotions are created and sustained at the organisational level of analysis. He notes, however, that this level is qualitatively different from the other levels because of its complexity and all-encompassing nature. Although this level contains many variables, here we focus on how organisational culture can influence employees’ responses before, during, and after failure in academic settings. First, however, it is important to distinguish between organisational culture and organisational climate. In a review of the concepts, Schneider, Ehrhart, and Macey define culture as ‘the shared basic assumptions, values, and beliefs that characterise a setting and are taught to newcomers as the proper way to think and feel, communicated by the myths and stories…’ (Reference Schneider, Ehrhart and Macey2013: 362). Climate, in turn, involves ‘the shared perceptions of and the meaning attached to the policies, practices, and procedures employees experience and the behaviors they observe getting rewarded and that are supported and expected’ (p. 362).

There is evidence to suggest moreover that organisational culture (and particularly cultural norms) play a key role in the experience and interpretation of failure in work settings. For example, in an investigation of the systematic biases that contributed to recognised project failures, Shore (Reference Shore2008) observed that ‘project culture’ – shared beliefs about project work practices, shaped by leader behaviours and organisational culture – helped to create an environment in which these systematic cognitive biases developed that, in turn, contributed to project outcomes. These biases include overconfidence, illusion of control and groupthink. Shore noted, however, that organisations can learn from others that have implemented change management practices to reduce the likelihood of such biases occurring.

We also contend that, if failures are viewed negatively in academic institutions rather than opportunities for analysis and organisational growth, this can lead to negative affective experiences for employees and inhibit organisational learning (Gino & Staats, Reference Gino and Staats2015). In particular, we suggest that normative beliefs that emphasise competition rather than collaboration, encourage punishment of employees’ mistakes, and discourage the open discussion of mistakes and mishaps can contribute to such outcomes. This is not uncommon. For example, Cannon and Edmondson (Reference Cannon and Edmondson2005) argue that organisational cultures (and in turn managers) frequently chastise employees following failed experiments, leading to a reluctance to adopt new approaches and ideas. It is therefore important that academic leaders examine how they (and their employees) perceive failure at work, and take steps to create a culture in which failure is openly acknowledged and accepted (Gino & Staats, Reference Gino and Staats2015).

‘Publish or perish’

The culture of academic institutions is, moreover, further embedded in an industry culture, which sets performance norms for the organisations within the culture (Cameron Cockrell & Stone, Reference Cameron Cockrell and Stone2010). In the academic context, we refer specifically to industry cultural expectations about academics’ publication output, an issue that has received attention anecdotally and in the scholarly literature and we believe is especially relevant to our discussion of failure. As we have argued already, academia generally speaking is a demanding, competitive and stressful profession, especially for graduate students and early career academics. For example, although many doctoral students desire greater work–life balance and the opportunity to spend time with family, academic culture has not evolved significantly in line with these changing attitudes (Mason, Goulden, & Frasch, Reference Mason, Goulden and Frasch2009; Cannizzo & Osbaldiston, Reference Cannizzo and Osbaldiston2016). Universities still hold rigid expectations of students, ‘including a de facto requirement for inflexible, full-time devotion to education and employment and a linear, lockstep career trajectory’ (Mason, Goulden, & Frasch, Reference Mason, Goulden and Frasch2009: 11).

In fact, and as Sang, Powell, Finkel, and Richards (Reference Sang, Powell, Finkel and Richards2015) observed, major structural changes in universities internationally have led to greater quantification of academic output, reduced autonomy, and in turn greater workload pressures. One of the strongest indicators of workload pressure is the ‘publish or perish’ culture that exists in academia (Rawat & Meena, Reference Rawat and Meena2014). Indeed, the very way that the term is phrased suggests that there is no alternative other than success; to fail is to perish, and to perish is to die. What are the implications of this cultural expectation for academics?

Research and anecdotal evidence suggest that the ‘publish or perish’ expectation leads to a range of consequences in higher education settings. For example, Miller, Taylor, and Bedeian (Reference Miller, Taylor and Bedeian2011) surveyed management faculty in multiple US business schools and found that pressure to reach publication targets comes from themselves, as well as academic leaders and colleagues. Unsurprisingly, these authors also found that tenure-track faculty feel the strongest pressure to publish of all, which seems to be driven by the knowledge that they will fail to receive tenure if they fail to reach publication targets.

As we observed previously, rejection in academia can be particularly distressing; therefore individuals will naturally seek to avoid this unpleasant experience. On a related point, Dooley and Sweeny (Reference Dooley and Sweeny2017) explored the means by which academics cope with the stress associated with waiting for a decision on a manuscript and identified a number of interesting results. In a survey of 130 academics in various disciplines, the authors found that less experienced researchers (with fewer publications and active submissions) spent more psychological energy anticipating the worst possible outcome, reported greater anxiety, and suffered more intrusive thoughts about the manuscript decision as compared with experienced scholars. Also unsurprisingly, they found that graduate students struggled the most with the stress of the waiting process. Dooley and Sweeny note, however, that the unpleasant emotions associated with waiting to receive feedback on a manuscript tend to reduce over time as academics gain greater publishing experience, knowledge, and identify coping resources, suggesting that there is cause for optimism.

Finally, several researchers (e.g., see Colquhoun, Reference Colquhoun2011; Barbour, Reference Barbuto, Gottfredson and Searle2015; Herndon, Reference Herndon2016) have observed that the ‘publish or perish’ culture appears to encourage unethical research practices, highlighting a troubling issue for universities worldwide. In this regard, Honig, Lampel, Siegel, and Drnevich (Reference Honig, Lampel, Siegel and Drnevich2014) argue that management scholars today (and especially graduate students) are under significant pressure to publish in the so-called ‘top tier’ journals, while competing for a small number of positions in a tight job market. Honig and his associates further note that there is increasing evidence (e.g., see Banks, Rogelberg, Woznyj, Landis, & Rupp, Reference Banks, Rogelberg, Woznyj, Landis and Rupp2016) that researchers (and even journal editors) engage in ethically questionable behaviours in this environment; and suggest that there is a need to develop more rigorous mechanisms to increase transparency and uphold ethical standards.

Additionally, evidence from the workplace deviance literature suggests that perceptions of unfairness and negative affective experiences play a key role in employees’ decisions to engage in unethical conduct in organisations (e.g., Reio & Ghosh, Reference Reio and Ghosh2009; Chen, Chen, & Liu, Reference Chen, Chen and Liu2013; Bauer & Spector, Reference Barbour2015; Kouchaki & Desai, Reference Kouchaki and Desai2015). In academic settings, we suggest that the negative emotions including jealousy, envy, frustration, and fear of failure are likely potent contributors to the decision to engage in deviant behaviour, and that cultural norms also likely play a role. Overall, we therefore conclude that the challenge for academic leaders is to help academics (and especially graduate students) to view publication rejections as learning opportunities rather than failures, while at the same time reinforcing cultural expectations around publication targets. Clearly this represents a challenging balance.

In closing, it is important to acknowledge that the drive to ‘publish or perish’ can also lead to constructive outcomes for academics; in our experience, this includes increased recognition and exposure, new research projects, and exciting opportunities for collaboration – all of which can be significant sources of positive emotions. Schaberg (Reference Schaberg2016) notes further that writing articles for publication ‘is better than sitting in meetings’ and can help to encourage engagement with students in the classroom. Therefore, while we recognise that the ‘publish or perish’ expectation is not inherently negative, we maintain that it can be a significant source of stress and uncertainty, especially in competitive, success-oriented environments.

NORMALISING THE EXPERIENCE OF FAILURE IN ACADEMIA AND BUILDING RESILIENCE

We began this article with the observation that failure is a common and often distressing experience in academic life. We offered a definition of failure before reviewing research into the nature of failure in organisational settings, including its antecedents and consequences. Next, we turned our attention to our topic of interest: the experience of failure in academic settings. Based on Ashkanasy’s (Reference Ashkanasy2003) five-level model of emotions in organisations, we explored how failure can occur at multiple levels of analysis in academic settings, ranging from within-person to organisation-wide. Therefore, in the next section of our essay, we argue that it is important to consider what we can do to prepare academics, especially the next generation of young scholars, for the experience, including the negative emotions involved. Again, we emphasise that our suggestions are not exhaustive, and we are hopeful that they will encourage further discussion into the meaning of failure in academia and how it can be managed (and coped with) effectively.

Most importantly, we contend that scholars need to start to acknowledge the reality of failure as a normal part of academic life and to talk about their failures truthfully with their colleagues. In our experience, very few academics honestly and openly acknowledge their mistakes and misfortunes, such as experiments that did not succeed, students who failed to achieve as expected, risks that did not pay off, manuscripts that were rejected, and other similarly disappointing outcomes (cf. Banks et al., Reference Banks, Rogelberg, Woznyj, Landis and Rupp2016).

It is heartening, however, to see that some academics have already started to do this in the form of ‘Failure CVs’ that list their misfortunes, including failed grant applications and rejected manuscripts. One of the earliest to do so was Johannes Haushofer, an assistant professor at Princeton University, who tweeted a link to his CV of failures in 2016. The CV included sections entitled ‘Research funding I did not get’ and ‘Academic positions and fellowships I did not get’ and generated considerable discussion online. Haushofer explained his reasons for exposing his rejections and disappointments to the world, noting that, ‘Most of what I try fails, but these failures are often invisible, while the successes are visible’, later lamenting that ‘This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention that my entire body of academic work’ (The Guardian, 2016).

In practice, we suggest that academic leaders, including Deans and Department Chairs, need to play a role in facilitating these discussions and shifting cultural norms such that failure is seen as a normal part of work life. For example, this could involve regular informal seminars where academics come together to discuss their recent failures and collectively to identify ways to move forward and to learn from the experience. Academics could also share with colleagues their personal strategies for coping with emotions such as disappointment, regret, and shame in this context. Research advisors could relate stories to their students about their personal mistakes and disappointments in their research careers. We suggest that universities can also play a role in encouraging this conversation. For example, the University of Oxford Careers Service recently developed a series of podcasts and a workbook for students to help them reflect on their failures, discuss them openly and honestly, and find ways to move forward (http://www.careers.ox.ac.uk/overcoming-failure). We suggest that such resources represent a valuable tool in helping students to normalise the experience and address maladaptive beliefs about perfectionism.

We also suggest that academic conferences could provide an excellent context for knowledge-sharing and learning from failure, especially for doctoral students and early career academics. Overall, rather than seeing failure as reason for blame and punishment, we propose that academics should acknowledge that failure in academia – as in organisations – can be an opportunity for significant learning, and that tolerance for failure can exist concurrently with high standards for performance (Edmondson, Reference Edmondson2011).

Many scholars have written frankly about their experiences and observations in the academic environment; and we suggest that much can be learnt from those who have failed (and succeeded) before us. Some have shared simple tips for coping with failure in academia (e.g., Clark & Sousa, Reference Clark and Sousa2015) while others have focused specifically on their experience being rejected for tenure (e.g., Diascro, Reference Diascro2016). Others still have considered how we view success and failure in academia and how this can be changed. In an exceptionally thoughtful discussion (Cheplygina, Reference Cheplygina2017), Eric Grollman, an assistant professor at the University of Richmond, proposed the possibility of shifting our view of success from a purely quantitative approach, noting that, ‘Maybe we could celebrate that it took 5 years to publish an article because it kept getting desk-rejected and not just the impact factor of the journal in which it is published. Or celebrate the personal backstory of an article, like persevering despite a neglectful, abusive former co-author, and not just that it was published and will be widely cited.’ Other academics have written about the double-edged sword of academic success (Marx, Reference Marx1990), and how to cope when a manuscript is rejected (Martin, Reference Martin2013; Ray, Reference Ray2015; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2015). We suggest that these anecdotal observations are valuable and important and should be shared widely to help academics realise that they are not alone.

Finally, we propose that evidence from studies of coping with failure in organisational settings (e.g., Shepherd, Colvin & Kuratko, Reference Shepherd, Covin and Kuratko2009) could potentially be applied to the experience of failure in the university environment. For example, Shepherd (Reference Shepherd2003) argues that self-employed individuals whose businesses fail go through a grieving process that is in many respects similar to the loss of a loved one, and discusses potential coping strategies that may reduce grief and enhance learning from the experience.

We suggest that these same coping strategies could be highly relevant following failure in academia. We also note that Shepherd’s (Reference Shepherd2004) work about how to teach entrepreneurship students about the role of emotion in learning from failure is especially relevant here. Specifically, Shepherd suggests that educators can use multiple approaches to maximise students’ learning, including lectures, guest speakers, case studies, role plays, and simulations. We argue that a similar approach could be used to develop a seminar or series of lectures to teach doctoral students about how to cope with inevitable failures they will encounter in academic life. While all universities take rigorous steps to ensure that doctoral students have the required knowledge, skills and competencies to pursue a demanding programme of research, in our experience few make a serious attempt to ensure that PhD students have the emotional resiliency to cope with the associated stress. Increasing these students’ awareness of the culture in academia, the challenges that they will face, and identifying coping strategies ahead of time would be a step in the right direction.

FUTURE RESEARCH AGENDA

As we noted throughout this article, relatively few scholars have explored academics’ experiences of failure at work and their associated affective experiences. This would seem to open up many opportunities for future study. The anecdotal evidence we highlighted suggests moreover that academic failure is often associated with significant consequences for employees, especially graduate students and early career academics. In this section, we propose how researchers might begin to explore the relationship between failure and emotions in academic settings, highlighting specific ideas for investigation at each level of analysis. We acknowledge that our suggestions here are not all-encompassing, however, and we actively encourage researchers to extend these ideas further and explore new directions in subsequent work.

Level 1: Within-person

At the individual level, we propose that it is important firstly that researchers begin to identify the discrete emotions associated with failure in academic settings. Researchers can do this using a range of different approaches, including laboratory experiments, situated experiments (Greenberg & Tomlinson, Reference Greenberg and Tomlinson2004), diary methods (DeLongis, Hemphill, & Lehman, Reference DeLongis, Hemphill and Lehman1992), and Experience Sampling Methods ([ESM] Kubey, Larson, & Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Kubey, Larson and Csikszentmihalyi1996). Building on our argument that affective events theory can be used to explain how academics’ negative emotional experiences following failure directly influence their attitudes and behaviours, we suggest that ESM may be an especially useful tool to use in this context. Kubey, Larson, and Csikszentmihalyi describe ESM as an approach that involves gathering ‘self-reports made by respondents as they go about their everyday activities’ (Reference Kubey, Larson and Csikszentmihalyi1996: 99). ESM is usually executed today using smartphone or computer communication (Fisher & To, Reference Fisher and To2012) where participants are contacted at random times during the working day asking them to record their responses on the spot to survey questions (Kubey, Larson, & Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Kubey, Larson and Csikszentmihalyi1996). Thus ESM allows researchers to capture participants’ discrete emotional experiences in real-time, reducing threats to validity associated with the retrospective recall of emotions (see Levine & Safer, Reference Levine and Safer2002).

In a recent chapter, Goetz, Bieg, and Hall (Reference Goetz, Bieg and Hall2016) argued that ESM is especially well-suited to exploring the role of emotions in teaching and learning settings, highlighting in particular its ecological validity. These authors also note some of the challenges of using ESM, noting that it can be time-intensive and costly and is still a self-report measure. Despite these potential difficulties, we suggest that ESM represents an excellent potential method to investigate academics’ everyday affective experiences, including their experience of failure.

Level 2: Between-persons

Moving to the between-persons level of analysis, we propose that future researchers could investigate the individual difference variables that influence academics’ cognitive, affective, and behavioural responses to failure at work. Firstly, we argue that researchers would do well to focus their attention on building rigorous theoretical models of the potential relationships between variables, then testing their models in turn. While we have highlighted three potential variables of interest in this essay – perfectionism, job identification and emotional intelligence – we suggest that many other moderating (and mediating) variables could be investigated in this context. These could include additional personality traits (e.g., narcissism, neuroticism), job attitudes, achievement motivation, stress tolerance, and beliefs about ethical behaviour, in addition to standard demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, cultural background, tenure in the organisation, etc.). We suggest that studies of the key variables that influence employees’ responses to episodes of failure in the workplace generally could be a good starting point for investigation. This could be addressed using quantitative methods such as self-report surveys, laboratory experiments, and field studies.

We also highlight the importance of recognising and investigating further how academic culture, including harmful beliefs about failure, can contribute to the development of mental illness in especially vulnerable scholars. As we have noted already, graduate students appear to be particularly at risk of struggling with the demands of academia. In a 2014 study, Garcia-Williams, Moffitt, and Kaslow found that graduate students are ‘a population that experiences high levels of depression, anxiety, and distress’ (Reference Garcia-Williams, Moffitt and Kaslow2014: 558), with 7.3% of students in their sample reporting thoughts of suicide. This finding along with other work (e.g., Winefield, Gillespie, Stough, Dua, Hapuarachchi, & Boyd, Reference Winefield, Gillespie, Stough, Dua, Hapuarachchi and Boyd2003; Shaw & Ward, Reference Shaw and Ward2014; England, Reference England2016; Gorczynski, Reference Gorczynski2018) suggests that mental illness remains a pervasive issue in higher education settings. We therefore strongly encourage researchers to investigate how we can best support academics to facilitate greater well-being, build resiliency and increase work–life balance while working in a demanding, high-pressure environment.

Level 3: Interpersonal

At the interpersonal level, we propose that researchers can build upon the findings into the discrete emotions involved in the experience of academic failure to explore how, when, and why academics engage in emotional labour following failure at work. Researchers could also explore the consequences of engaging in emotional labour over time (e.g., in the face of ongoing failures), and whether certain types of failures are associated with specific strategies (i.e., surface acting or deep acting). We also propose that researchers would benefit from exploring whether academics at different stages of their careers engage in more less emotional labour in the workplace.

We note in this regard that previous researchers studying emotional labour have used both qualitative (e.g., Henderson, Reference Henderson2001; Harris, Reference Harris2002; van Gelderen, Heuven, Van Veldhoven, Zeelenberg, & Croon, Reference van Gelderen, Heuven, Van Veldhoven, Zeelenberg and Croon2007) and quantitative methods (e.g., Johnson & Spector, Reference Johnson and Spector2007) to inform their understanding of the phenomenon, and we suggest that multiple methods could be utilised here. For example, Ogbonna and Harris’ (Reference Ogbonna and Harris2004) used semi-structured interviews to explore the frequency and propensity of emotional labour among university lecturers in the United Kingdom, in addition to its antecedents and consequences. Future researchers may therefore wish to explore the relationship between academic failure and emotional labour using qualitative methods such as interviews, diary studies, and/or ethnography, and use these findings to inform the development of quantitative studies. We note that ESM has also been used successfully in studies of emotional labour (e.g., Totterdell & Holman, Reference Totterdell and Holman2003; Judge, Woolf, & Hurst, Reference Judge, Woolf and Hurst2009; Keller, Chang, Becker, Goetz, & Frenzel, Reference Keller, Chang, Becker, Goetz and Frenzel2014) and suggest that this may also be a useful tool to adopt in this context.

Level 4: Groups and teams

As we explained earlier, at this level of analysis we argue that leaders play a key role in shaping employees’ perceptions of and reactions to episodes of failure in academic settings. We suggest that this level of analysis in particular offers several interesting avenues for further investigation. First, researchers could explore the extent to which leader characteristics and behaviours influence academics’ emotional responses to failure at work. As we noted already, this could involve an assessment of leader EI, as well as leader personality traits. We suggest that researchers could also use qualitative methods such as interviews to explore how academic leaders create a climate of psychological safety within their departments, how they help their employees develop resiliency following episodes of failure, and how current leaders can mentor and support the development of failure-tolerant leaders in the next generation of scholars.

Building on work into Leader-Member Exchange theory (Day & Miscenko, Reference Day and Miscenko2016), we propose that researchers could also investigate how the quality of the leaders’ relationships with individual academics helps to shape their affective reactions to failure, especially in the context of teamwork. Although we have only touched on this topic briefly in our essay, we suggest that the experience of failure in academic teams is an especially interesting avenue for future enquiry; both qualitative (e.g., ethnography, diary studies) and quantitative methods could be utilised to explore the affective antecedents and consequences of failure here. Questions that can be looked at in this regard include: How do academics and graduate students manage the experience of failure in a team? What kind of discrete emotions emerge, and what is the role of emotional contagion in this context? What kind of leader behaviours are especially important when helping a team recover from failure in a research setting?

Level 5: Organisation-wide

At the top level of analysis, we suggest that an important area for future investigation concerns the role of organisational culture and climate in employees’ affective responses to failures in academic settings. As we noted at the beginning of this article, many researchers have observed that it is important that organisational leaders create a climate in which ‘intelligent failures’ (Edmondson, Reference Edmondson2011) are encouraged and failures are framed as learning opportunities rather than incidents that should attract punishment. We acknowledge, however, that this is a challenge in the highly competitive, demanding environment of academia, where academics are told that they must ‘publish or perish’. Future researchers could explore how academic leaders manage these competing demands, and investigate how to build a failure-tolerant climate in academia.

CONCLUSION

In opening this article, we argued that failure is an all-pervasive fact of life in academia, and a phenomenon that academics need to deal with throughout their careers. With this in mind, we adopted Ashkanasy’s (Reference Ashkanasy2003) model to explore the relationship between failure and emotions at five levels of analysis, and in doing so highlighted key areas for future study. Overall, we suggest that failure is almost inevitably associated with negative emotions that pervade five levels of analysis: from the need for academics to deal with ‘affective events’ right through the norms that exist in academic institutions and that set the standards by which academics must manage their failures and associated negative emotions on a day-to-day basis. In considering the experience of failure in academic settings and the role of emotions in this context, we are hopeful that our discussion will inspire other scholars to investigate these ideas in more depth. While we do not expect that academic culture, in particular, will shift dramatically, we are heartened by the fact that scholars are beginning to acknowledge the normality and inevitability of failure in academic life and view it as an opportunity for learning. We hope that our conversation here will contribute to this growing momentum and ultimately improve the experiences of academics in future.

About the Authors

Marissa S Edwards is a teaching-focused academic at the UQ Business School. She is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and her research interests include business ethics, emotions, and mental health and well-being.

Neal M Ashkanasy is a Professor of Management at the UQ Business School. His research focuses on emotions in organisations, leadership, organisational culture, ethics, and his work has been published in leading journals in the field. In 2017, he was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia.