Ancient sources present the running ritual of the Luperci as the most prominent feature of the Lupercalia, and modern scholars also first think of this when the festival is mentioned. For instance, in her book on the triumph, Beard writes:

Ask the question: ‘What happened at the Lupercalia, or the Parilia?’ and the answer will come down to the one or two picturesque details: the dash round the city at the Lupercalia; the bonfire-leaping at the Parilia. We could not hope to give any kind of coherent narrative of the festivals. (Beard, Reference Beard2007: 81)

As Beard goes on to say in relation to the triumph (itself better attested than the Lupercalia), reconstructing the route that a particular Roman ritual took is no easy task. One would first have to suppose that the route was prescribed and never significantly changed, a supposition that can rarely be made with certainty. However, giving a general picture excludes singular occurrences, but is in many cases still a good way to present a pattern that was considered typical (Beard Reference Beard2007: 91–106). Thus we have to allow for some form of idealization in describing the course of the Luperci while bearing in mind that I seek to posit no absolute rules. It is worth pointing out that ritual topography encourages exploration in this direction as many myths and rituals in Roman religion were closely tied to specific places so strongly that the connection to a location was preserved even when other elements significantly changed.Footnote 1

THE LUPERCAL

The most important location for the festival is the starting point of the running ritual, the Lupercal cave. This was a sanctuary dedicated to Faunus, and the place where the sacrifice of a he-goat and dog was offered to him before the running started. It is unclear whether these offerings were made inside or outside the cave, but it seems the Lupercal was the place of rituals we know little about. Varro's short note on the etymology of the Luperci (quod Lupercalibus in Lupercali sacra faciunt, ‘because they perform their rites at the Lupercal on the Lupercalia’) as well as Plutarch's tantalizing description of a curious blood rite (where two young men were smeared with the blood of the freshly sacrificed goats) are only glimpses into what was probably a more elaborate ceremony.Footnote 2 Of course, in Lupercali need not be taken literally, as ‘in the very cave’, but can also denote the general location ‘in the area of the Lupercal’/‘at the Lupercal’. It is very likely that at least some of the rituals (especially the animal offerings) took place outside, in front of the cave. Nevertheless, if we were able to ascertain the exact location of the Lupercal and submit it to archaeological scrutiny, the research might yield interesting results. Literary sources position the Lupercal at the southwest foot of the Palatine,Footnote 3 but the inability to locate it precisely has contributed to the lack of scholarly attention the cave has received. The Lupercal is a unique religious site as the only cave that we know to have been a sanctuary in Republican Roman religion.

However, caves were also sacred sites in other areas of Italy (e.g. Grotta del colle di Rapino and Grotta Bella in Umbria), and in Greek religion caves that served a religious purpose are well attested. In her study of several caves that served as sanctuaries dedicated to the nymphs, Pache (Reference Pache2010: 37–70) notes that in all cases the worshippers would create a whole series of artefacts related to the cult of the nymphs (vases, inscriptions, sculptures, etc.), thus transforming the cave in the process. Our sources say that a statue of the babes being suckled by the she-wolf was situated at the Lupercal and an inscription mentions an equestrian statue of Drusus (Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 1.79.8; Liv. 10.23; CIL VI 912). Bearing the Greek parallel in mind, we can only speculate on the amount of archaeological evidence we would have at our disposal if the cave sanctuary were to be discovered. We may wonder what exactly is implied in the words ‘Lupercal … feci’ in the Res Gestae (a mere restoration or a complete rebuilding?), but the fact that Augustus lists the Lupercal with many great temples he ‘restored’ indicates that this was a well-furnished cult centre.Footnote 4

To draw on a parallel closer to Rome, the mithraea that we find scattered throughout the Roman Empire were often adapted natural caves or underground chambers built in imitation of the cave where Mithras killed the bull. As literary evidence on the cult of Mithras is scarce and difficult to interpret, scholars have had to rely on archaeological evidence in their study of mithraea.Footnote 5 It is well known that Mithraists used caves for rituals of initiation. However, in our case, the lack of archaeological evidence prevents us making inferences from anything other than the literary sources that position the rituals ‘at the Lupercal’. This again calls for comparative parallels to illuminate what the choice of a cave as a sanctuary for the festival could tell us about the Lupercalia. In her ground-breaking study on caves in Greek culture, Ustinova (Reference Ustinova2009: 28–32) uses neuroscience and cognitive psychology to illuminate the role of caves in religion. A cave is a place of transcendental experience and is perceived as an entrance to the world of the dead and chthonic gods. This fits the profile of the Lupercalia, as a number of sources connect the festival with commemoration of the dead.Footnote 6 As opposed to man-made temples and sanctuaries, a cave is a feature of the natural landscape that creates a sense of mystery and fascination with the divine.

The cave Lupercal plays a key role in the Roman foundation myth, which overlaps with the mythology of the festival in the childhood and adolescence of Romulus and Remus.Footnote 7 The ficus Ruminalis, ‘the fig-tree of Romulus’, stood in front of the Lupercal as a permanent spatial reminder of the close connection. If creation myths have their trees of life, the Roman foundation myth has the fig as its sacred tree, a symbol of fertility and new life for the young twins.Footnote 8 The sources identify this as the place where the she-wolf nursed them.Footnote 9 Consequently, they most frequently derive the name from rumis/ruma (‘dug’).Footnote 10 The whole southwestern corner of the Palatine was called Cermalus and derived from germani, the twins.Footnote 11 In both cases, associations go back to the foundation myth and the udders of the she-wolf that suckled the boys. It is quite possible that this particular tree, which was thought to be an arbor felix (see Macr. Sat. 3.20.2–3), was selected to reflect the ancient myth. It does not take a psychoanalyst to recognize that the fruit of the plant has the shape of a female breast and emits a white sap reminiscent of milk (Ogilvie, Reference Ogilvie1965: ad Liv. 1.4.5).

There was also a cult of diva Rumina, the goddess of suckling, and apparently shepherds offered her milk instead of wine in a sanctuary next to the fig tree.Footnote 12 It is here that Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Ant. Rom. 1.79.8) could still recognize ‘bronze figures of ancient workmanship’ representing the she-wolf with the twins, whether or not this was the same statue that the Ogulnii brothers erected in 296 bc.Footnote 13 The Palatine surroundings of the Lupercal also included other monuments that pointed to the foundation, such as the famous casa Romuli.Footnote 14 In other words, the whole complex was a set of lieux de mémoire, replete with the mythology of the foundation, essential in the formation of Roman historical consciousness (Rodriguez-Mayorgas, Reference Rodríguez Mayorgas2010: 100, Coarelli, Reference Coarelli2012: 127–89).

Dionysius is also our main source for the positioning of the Lupercal itself. He tells us that ‘the area around the sacred precinct has been united with the city’ (Ant. Rom. 1.32.4) and that ‘the cave from which the spring flows is still pointed out, built up against the side of the Palatine hill on the road which leads to the Circus’ (Ant. Rom. 1.79.8). We should connect this with the information provided by Velleius Paterculus on the construction of a theatre in front of the temple of Magna Mater in 153 bc (Coarelli, Reference Coarelli2012: 276–82). The theatre was placed a Lupercali in Palatium versus (‘from the Lupercal facing the Palatine’), implying that the Lupercal itself was situated below the theatre, which must have been sizeable enough to house the plays of the Megalensia.Footnote 15 Velleius’ description concurs with Dionysius’ placing of the Augustan Lupercal ‘on the road which leads to the Circus’ for this is almost certainly the vicus Tuscus,Footnote 16 especially when we consider other passing references that place the Lupercal sub gelida rupe, sub monte Palatino, in radicibus Palatii and finally in Circo.Footnote 17 Considering all the literary evidence, I must agree with Coarelli's conclusion that the Lupercal was situated on the southwestern slope of the Palatine, somewhere in the triangle formed by the Scalae Caci in the east, Velabrum in the west, and the temple of Magna Mater in the north (see map, Fig. 1) (Coarelli, Reference Coarelli2012: 132–9). The question remains as to the southern limit of the area. Allowing enough space for the theatre under the temple of Cybele and considering the fact that our sources position the Lupercal under the Palatine as well as ‘in Circo’, we may conclude that the Lupercal should be in the southern portion of the delimited triangle, not far from the Circus.

Fig. 1. Carandini's and Coarelli's positioning of the Lupercal compared (after Coarelli, Reference Coarelli2012: 137, fig. 34, ‘Posizione probabile del Lupercal’). Reprinted by author's permission.

This brings us to an interesting proposal made by Fabio Gori and John Henry Parker,Footnote 18 who in their joint essay of 1869 suggested that the Lupercal was the cave they had found near the church of Santa Anastasia at the corner of the ‘Via de’ Cerchi and the Via de’ Fienili’ (currently Via di S. Teodoro).Footnote 19 They describe ‘a subterranean cave-reservoir, partly natural and partly built’ with a spring of running water that pours into a channel (which takes it down to the arch of Janus and the Cloaca Maxima). It was divided into two portions of considerable length.Footnote 20 The description closely matches that of Cardinal Macchi who conducted excavations in the area in 1859, and also reported finding a cave with a spring and three chambers of similar length (Iacopi, Reference Iacopi1997: 23). Gori and Parker (Reference Gori and Parker1869: 7) saw remains of stucco still attached to the vault as well as brickwork and a niche with opus reticulatum.

The location of the underground chambers at the foot of the Palatine (so near the Circus) makes it a potential candidate for the ancient Lupercal. There are problems, of course. The length of the two chambers (36 and 37 yards (33 and 34 m)) as well as the shape Gori and Parker describe may indicate a substructure rather than the ancient sanctuary of the Lupercal, especially as the walls stand right adjacent to the Circus and may have been used to support additional seats built during the Empire.Footnote 21 Without further archaeological investigation, it is difficult to draw any substantial conclusions from the finding.

One feature that makes the Gori–Parker hypothesis attractive is the presence of running waterFootnote 22 as we saw that the only substantial description of the cave in antiquity (by Dionysius) explicitly involves a spring. Gori and Parker's (Reference Gori and Parker1869) proposal has been ignored in subsequent scholarship. The underground chamber was apparently used for a mill, and Gori accessed it through a well descending 4 m underground.Footnote 23 The area has considerably changed in the modern period (Borghi and Iacopi, Reference Borghi and Iacopi1986: 481–5) and the Via dei Cerchi is now constantly open to traffic, which makes direct investigation impossible. Nevertheless, whatever one makes of the hypothesis, it indicates that modern archaeological research is needed in this spot and the general area to the south of the triangle delimited by Coarelli (above) between the Circus and the church of Santa Anastasia. It is here that we may expect to find the ancient Lupercal (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Map used in Parker (Reference Parker1878: plate XLIV.II) indicating the location of his and Gori's find.

On the other hand, archaeological research was conducted to the northeast of this area in the complex of the house of Augustus. In 2007, Iacopi and Tedone of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma reported on a fascinating find of a circular rotunda 8 m high and 7.5 m in diameter. Probes were sent 16 m underground and took pictures of the grotto that revealed a richly decorated ceiling with coloured mosaics and seashells, and a representation of an eagle at the top of the dome. This immediately caused a great flurry in the media as Andrea Carandini identified the newly discovered grotto as the Lupercal.Footnote 24 He was criticized by many of his Italian colleagues who were much more cautious in their conclusions. Carandini then published La Casa di Augusto (a book co-authored with his student Daniela Bruno), where he struggled to prove the identification (Carandini and Bruno, Reference Carandini and Bruno2008: 8–12).

First, he took Dionysius' street that leads to the Circus to be not the vicus Tuscus, but a ‘strada parallela a quella immediatamente esterna al Circo, dove passava il limite fra le regioni X e XI’ (Carandini and Bruno, Reference Carandini and Bruno2008: 11). The street is not mentioned by any ancient source, but its archaeological remains were found lining the southern edge of the church of Santa Anastasia (Whitehead, Reference Whitehead1927: 405–10). Thus, this would still be closer to the above-delimited triangle (than it is to Carandini's grotto), if one wants to accept this reading of Dionysius. Furthermore, according to Carandini himself, the grotto is at least 66 m away from the location where we should expect the Lupercal considering Velleius’ information on the theatre of Longinus.Footnote 25 Servius’ note on the Lupercal as positioned ‘in Circo’ should be translated as ‘at the Circus’ (implying proximity rather than an exact location), but Carandini's grotto is by any account too far from the arena.

Additionally, as Fausto Zevi and Adriano La Regina pointed out immediately after the news came out, what the pictures show is typical of a nymphaeum: a rotunda decorated with seashells and coloured mosaic.Footnote 26 Carandini (Reference Carandini and Bruno2008: 12–18) then goes into a long discussion of the representations of the Lupercal in Roman art, but none of these in fact shows the interior of the cave, and the artistic depiction of the she-wolf motif at a particular point in the pictures can hardly be taken as evidence for the topographical location of the Lupercal.Footnote 27 However, we saw that the Cermalus is a topographical entity, and the foundation myth insists on positioning the cave right next to the area flooded by the Tiber. Although the ground level of this area has been considerably elevated since antiquity, Carandini's location for the Lupercal is still too far up the slope of the Palatine for it to be reached by the Tiber floods.Footnote 28 Thus, we may conclude that this grotto is by itself a fascinating rediscovery, but is not the Lupercal.

The lower part of the Cermalus is the location of not only the Lupercal, but of the ficus Ruminalis. It is well known that this fig tree had a counterpart in the Forum. Faunus, the god of the Lupercal, had many epithets, one of which was ‘Ficarius’.Footnote 29 His divine counterpart Silvanus had a statue in front of the temple of Saturn, where another fig tree stood until it endangered the statue with its expanding roots. According to Pliny (HN. 15.77), the Vestals then transplanted it to the Comitium, in medio foro.Footnote 30 Tacitus reports that its branches began to wither in ad 58, which was considered ominous (Tac. Ann. 13.58). The presence of a fig tree in the Forum, originally in front of the statue of Silvanus, was meant to reflect the fig tree at the Lupercal (as the sanctuary of Faunus); it thus connected two places which the Luperci visited as they ran.Footnote 31 For the presence of these priests at the Lupercal and the Forum is indisputable. However, how did they get from one place to the other?

THE COURSE OF THE LUPERCI

This brings us to the second major issue of Lupercalian topography, the course of the Luperci. For a long time modern scholars maintained that the Luperci made a circuit around the Palatine, basing this on a passage of Varro (Ling. 6.34):

Dehinc quintus Quintilis et sic deinceps usque ad Decembrem a numero. ad hos qui additi, prior a principe deo Ianuarius appellatus; posterior, ut idem dicunt scriptores, ab diis inferis Februarius appellatus, quod tum his paren < te > tur; ego magis arbitror Februarium a die februato, quod tum februatur populus, id est lupercis nudis lustratur antiquum oppidum Palatinum gregibus humanis cinctum.

Therefore the fifth month is called Quintilis and so all the others up to December by their respective number. As to the months which were added to these, the first was called Ianuarius from the god who comes first. The following one, as the same writers say, Februarius from the gods of the underworld, as they are then placated. I am more of the opinion that February received its name from the februated day, for on that day the people is purified (februated), i.e. the ancient city of Palatine, encircled by groups of people, is lustrated by the naked Luperci.

For almost a century, this passage was taken as prime evidence that the Luperci circled the Palatine. In 1863, Preller understood the phrase gregibus humanis as referring to the Luperci, and cinctum as signifying their circular course around the Palatine. Jordan adopted Preller's identification of the Luperci as greges humani, and was followed by Marquardt and Wissowa, whose great authority helped to facilitate the general acceptance of the theory.Footnote 32 Michels challenged this view in 1953, and, relying on Mommsen, pointed out that the sentence would be circular if gregibus humanis referred back to the Luperci. It is indeed difficult to imagine Varro saying that ‘the Luperci lustrate the Palatine which is encircled by the Luperci’. We saw earlier that Varro is not free from providing circular definitions in his etymologies, but even if he wanted to refer back to the Luperci, why use a phrase such as greges humani? Michels (Reference Michels1953: 49) offers an imaginative explanation: the phrase was used to signify the Luperci in their capacity as the souls of the dead. As much as one would like to see in Varro the conclusion we arrive at using modern comparative research (see Kershaw, Reference Kershaw2000: esp. 122–4), this particular phrase cannot be twisted to yield that sense.

What Varro is referring back to in gregibus humanis cinctum is the populus. The Luperci lustrate the Palatine and the people, groups of whom surround the hill in expectation of the running ritual. The word grex in Latin can signify both human and animal groups just like its cognate gaṇa in Sanskrit (see Ernout and Meillet, Reference Ernoult and Meillet1979: s.v.). There is nothing to say that the word grex implies animal groups (flocks).Footnote 33 The word cingere has static connotations, as Michels (Reference Michels1953: 58) herself elaborated. Its primary meaning is ‘gird, surround’ and here it refers not to the running Luperci, but to the people standing in their way in expectation of the blows.Footnote 34 When Ovid says that the Luperci lustrate crowded streets (celebres vias),Footnote 35 he is also referring to the multitude of people around the Palatine.

Debates on the course of the Luperci have developed from the fact that the only three places that the sources explicitly state they visited are the Lupercal, the Forum and the Sacra Via. Thus, Michels postulated a course for the Luperci which has them start at the Lupercal, run to the Sacra Via and end at the Forum.Footnote 36 Her view was accepted by several scholars (with more or less modification) (Ulf, Reference Ulf1982: 63–6),Footnote 37 as well as her interpretation of a passage of Augustine, which editors include among the fragments of Varro. It is thus very important to thoroughly investigate both issues in our discussion, something that has not been done so far. The attribution of Augustine's citation to Varro (Fraccaro, Reference Fraccaro1907: fr. 21; Wiseman, Reference Wiseman1995a: 7–8) is far from certain.Footnote 38 Let us have a closer look at what is really said (C.D. 18.12):

Per haec tempora, id est ab exitu Israel ex Aegypto usque ad mortem Iesu Nave, per quem populus idem terram promissionis accepit, sacra sunt instituta diis falsis a regibus Graeciae, quae memoriam diluvii et ab eo liberationis hominum vitaeque tunc aerumnosae modo ad alta, modo ad plana migrantium sollemni celebritate revocarunt. Nam et Lupercorum per sacram viam ascensum atque descensum sic interpretantur, ut ab eis significari dicant homines qui propter aquae inundationem summa montium petiverunt et rursus eadem residente ad ima redierunt.

Through these times, that is from the exodus of Israel from Egypt to the death of Joshua, son of Nun, through whom that people gained the promised land, the Greek kings instituted rites to false gods, which by a regular celebration invoked the memory of the flood and of men's liberation from it and of the harsh existence that the people then suffered as they had to move between plains and hills. For they interpret this way the ascent and the descent of the Luperci along the Sacra Via, and say that they signify the men who sought the hilltops because of the inundation of water and then returned to the lowlands when it retreated.

Augustine here continues his discussion of the book of Exodus from the previous passage, and it is from this Judaeo-Christian perspective that he interprets the Lupercalia. It is not at all clear who ‘they’ in the second sentence are (in interpretantur, dicant), and I do not see why this should be Varro's interpretation. Granted, flood myths seem to be universal (see Witzel Reference Witzel, Binsbergen and Venbrux2010: 225–42), and they were certainly current in the Hellenistic world. Pausanias (10.6.2) transmits a similar story about one of the ancient names of Delphi, Likoreia. At the time of Deucalion's flood, the inhabitants followed the howling of wolves to the top of the mountain and reached safety where they founded a city named after the animals. Riposati (Reference Riposati and Collart1978: 64–5) argues that Varro might have used such a Hellenistic flood story to relate the Lupercalia to Greek mythology.

However, Augustine's report is much better understood in the context of his own work. Augustine refers to the Hebrew myth of the world flood, as a part of the biblical history he presents in book 18 of the City of God. True, in a previous passage he cites Varro as referring to Deucalion and Pyrrha, but he admits that this flood was limited to some parts of the world (chiefly Greece), and not universal like the Hebrew one.Footnote 39 He also specifies (C.D. 18.8) that neither Greek nor Roman history knows of a universal flood. The whole of book 18 is marked by Augustine's efforts to connect two separate strains of narrative, the biblical and Greco-Roman.Footnote 40 In this process, the ancient festival of the Lupercalia becomes entangled with the oldest strain of Hebrew myth in Genesis. This mechanism is well documented in late antiquity: biblical authority takes precedence over ‘pagan’ myths, which consequently become interpreted in a Judaeo-Christian framework (see now Busine, Reference Busine, Engels and van Nuffelen2014: 220–36). We may conclude that the ‘they’ in Augustine's sentence are more likely to be Christian historians or simply his friends in Rome rather than Varro.

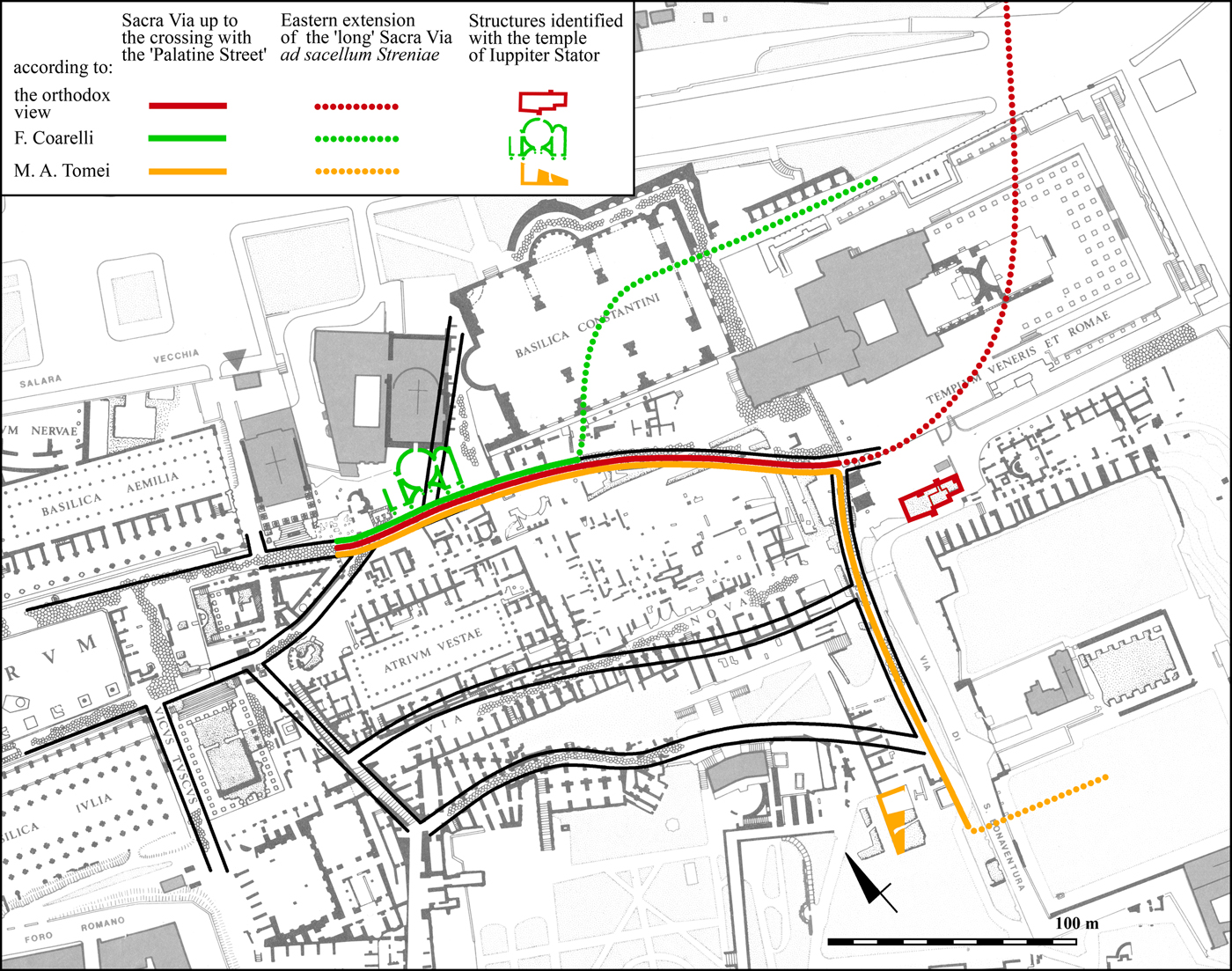

Augustine's information on the Luperci ascending and descending the Sacra Via does not contradict the crowds encircling the Palatine.Footnote 41 There is no doubt, even for Michels, that the Luperci started from the Lupercal, which is at the southwest foot of the Palatine. The Sacra Via runs north of the hill and its western end goes through the Forum up to the Arx on the Capitol. Now, the exact extent of the Sacra Via changed through time, but it always stretched along the northern end of the Palatine from where it sloped down towards the Forum (see map, Fig. 3). In the debate on its extent, two sources are used in the attempt to delineate the street. One is Varro (Ling. 5.45) again:

Carinae pote a caerimonia quod hinc oritur caput sacrae viae ab Streniae sacello quae pertinet in arce < m>, qua sacra quotquot mensibus feruntur in arcem et per quam augures ex arce profecti solent inaugurare. huius sacrae viae pars haec sola volgo nota, quae est a foro eunti primore clivo.

‘Carinae’ is derived rather from ‘caerimonia’ because from here at the shrine of Strenia starts the head of the Sacra Via which stretches to the Arx. By this street the offerings are brought to the Arx in each month, and along it the augurs go when they start out from the Arx to perform the auguries. Of this Sacra Via only this one part is known as such among the people, which is on the first ascent when you go from the Forum.

Varro gives the full extent of the Sacra Via, pointing out that it was also popularly known in a more narrow sense. His vague expression primore clivo caused the modern debate about what exactly is meant. Festus (372L) is more precise:

Sacram viam quidam appellatam esse existimant, quod in ea foedus ictum sit inter Romulum ac Tatium; quidam, quod eo itinere utantur sacerdotes idulium sacrorum conficiendorum causa. Itaque ne eatenus quidem, ut vulgus opinatur, sacra appellanda est a regia ad domum Regis sacrificuli, sed etiam a Regis domo ad sacellum Streniae, et rursus a regia usque in arcem.

Some think the Sacra Via was so called because in it an alliance was struck between Romulus and Tatius: some, because the priests use that route to perform the rites of the Ides. Therefore, it is to be called the Sacra Via, not only to this extent, from the Regia to the house of the Rex sacrificulus, as the people think, but also from the home of the Rex to the shrine of Strenia, and back from the Regia all the way to the Arx.

Fig. 3. The red line represents the course of the Sacra Via now agreed on by both Ziolkowski and Coarelli. (After Ziolkowski, Reference Ziolkowski2004: fig. 1, ‘Recent hypotheses on the course of the pre-Neronian Sacra Via and the position of the temple of Iuppiter Stator’.) Reprinted by permission of the Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation.

Despite Festus’ clarity, archaeological debates have continued since it is difficult to determine the precise location of the domus Regis sacrificuli (see Carandini, Reference Carandini2004: 58–60). Coarelli closely follows the two ancient accounts by arguing that there were two concurrent concepts of the Sacra Via in antiquity: one running from the Arx to the sacellum Streniae in the Carinae (see Fig. 3), and the other a more common ‘short’ version which defined it more loosely as running from the Regia in the Forum to the summa sacra via (the top of the Sacra Via), the highest point of the street as it goes up the northern side of the Palatine (Coarelli Reference Coarelli1983: 11–79; summary in Coarelli, LTUR, s.v.). The former, longer version would be the antiquarian definition (known to the savants) and the latter a view held by the common people. Ziolkowski (Reference Ziolkowski2004: 111–19) has demonstrated that the longer version was not restricted only to antiquarians, but was understood by other ancient sources and attested on inscriptions. However, both Coarelli and Ziolkowski have now agreed that the Sacra Via did have two concurrent concepts in antiquity.Footnote 42 It is not at all unusual for a particular toponym to be known in the more popular, narrow sense while a higher authority retains its original, wider definition.Footnote 43

When we connect Augustine's information with that presented by Festus and Varro, it becomes clear that the ascent and descent to which he is referring are a result of the natural geographical properties of the Sacra Via. The Sacra Via is popularly defined by the high point which it reaches rising from the Regia on the edge of the Forum along the northern slope of the Palatine. In that sense, much of the Sacra Via was considered a part of the Palatine, as in Latin any position from the base of the hill to its top was considered to be in Palatio.Footnote 44 How did the Luperci reach the street? Varro's note on lustration of the antiquum oppidum Palatinum has rightly been connected to Tacitus’ noteFootnote 45 on the early pomerium of Rome, which was later extended. The original pomerium encircled the Palatine just like the Luperci, marking the sacred space of the city on the hill. According to Tacitus, it went around the base of the Palatine, defined by the Ara Maxima and the altar of Consus in the south, and by the shrine of the Lares, Curiae Veteres and the area of the future Forum in the north (Tac. Ann. 12.24; Gell. 13.14.2). The shrine of the Lares was in summa sacra via, at the highest part of the street on the Velia, which brings us back to Augustine.Footnote 46

Theoretically, the Luperci could reach this point either from the western or eastern side of the Palatine. Michels preferred the former option, in which case they would have to ascend the slope of the Sacra Via going from the Forum. She discarded Plutarch's use (Rom. 21.4–5) of the noun περιδρομή as not necessarily implying a circular course but ‘right-about-face’, and similarly Dionysius’ use (Ant. Rom. 1.80.1) of περιέρχομαι she took in its rarer sense of ‘move about the city’ rather than around it. She concluded the discussion (1953: 46) with the claim that ‘a town may be purified by a ceremony performed in front of it as well as by a procession around it’. As a general statement, this might well be true, but in the case of Roman lustrations it is simply not the case. Lustration is a technical term for a ritual that involves circular motion, which is attested in numerous sources.Footnote 47

Even if circular motion were not clearly signified by Varro's use of lustrare (a point to which we return below), it is additionally explained by gregibus humanis cinctum, a phrase that implies the people girt the entire hill in expectation of the running Luperci. It is in line with this idea that Plutarch uses περιδρομή to describe the motion of the Luperci.Footnote 48

Ziolkowski rightly warned that Dionysius’ testimony is not very useful in reconstructing the course because he is imagining a Lupercalia celebration as it would appear in the primeval time of Evander's settlement, that is to say before a city was founded on the Palatine.Footnote 49 If we add the fact that this was tied to his ideological purpose of portraying Romans as originally Greek, no great conclusions should be drawn from this passage of Dionysius, as Michels (Reference Michels1953: 41–4) attempted in her detailed analysis. However, Ziolkowski (Reference Ziolkowski1998: 205) contradicts the ancient evidence by saying that the Luperci had no fixed route, but simply ran about ‘everywhere people were gathered’. He adds that their visiting the Forum and the Sacra Via was a later development and a natural consequence of this area becoming the centre of political life (where most crowds would normally gather).

In fact, the ancient evidence points to quite the opposite conclusion. Tacitus’ careful delineation of the ancient pomerium and Varro's note on the lustration thereof, as well as Augustine's observation of the Luperci on the Sacra Via, all in fact point to a great consistency in the route through the ages. As a lustration of the early Palatine city, the Lupercalia involved a circular motion around the hill and this trait was preserved in the ritual at least up to the time when Plutarch was writing his report. Augustine does not mention a circular motion because he is more concerned with his Christian interpretation, but he still places the Luperci on the Sacra Via, an area that they must have passed since the beginnings of the rite to perform the lustration of the Palatine, even before the Sacra Via itself became a city street.

However, Augustine's placing of the Luperci at this point presents a problem which Coarelli did not see because he (and many others) took it for granted that Augustine is citing Varro.Footnote 50 In imperial times, the whole of summa sacra via was built over first by the vestibule of Nero's domus aurea, and then by the temple of Venus and Rome (see map, Fig. 3) (Ziolkowski, Reference Ziolkowski2004: 119–30; Coarelli, Reference Coarelli2012: 29–35). Consequently, a considerable section of the Sacra Via disappeared, starting from the arch of Titus to the Compitum Acilii.Footnote 51 Seemingly, that leaves the Luperci only with the descent of the remaining Sacra Via if they are coming from the Curiae Veteres (in the east; see map, Fig. 4) on their circular course. However, there are several possibilities here that do not necessitate positing a semicircular course as Michels and her followers did.

Fig. 4. Map of the northeast corner of the Palatine (after Ziolkowski, Reference Ziolkowski2004: fig. 11, originally from Panella, Reference Panella1990: 54, fig. 20). Reprinted by permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e il Turismo.

Firstly, it should be pointed out that there is no evidence whatsoever that Augustine ever in fact saw the Luperci running.Footnote 52 His only stay in Rome came between the summer of ad 383 and autumn of ad 384 (when he was already in Milan), which would leave him with only one celebration of the Lupercalia to see, in February 384.Footnote 53 We do not know whether he used the possibility or not, but he certainly never claims that he did. In the above passage Augustine is twice referring to another source (interpretantur, dicant), not his own observation of events.Footnote 54 This Christian aetiology of the Lupercalia was created in the fourth century when this growing religion was looking for ways to explain old ‘pagan’ rituals within its own framework. The persistence of these rituals caused great unease to many Christians, a process that would culminate soon after Augustine's visit to Rome with the decrees of Theodosius I, and would still trouble Pope Gelasius more than a century later.Footnote 55 It is in this context that we find Augustine's citation of a source (written or oral?) that sought (like Augustine himself) to give a Christian meaning to an ancient ritual of the Lupercalia.

Thus, the ascent and descent in Augustine's description are of questionable value because they come from a secondary source and because they are a result of an attempt to fit the ritual into a preconceived Christian perspective. In this context, we should consider another possibility: Augustine was trying to make a Christian point (‘even pagan rituals attest our beliefs’) and he might not be aiming for the kind of precision of expression we would expect. Roman streets did not have signs as our streets do and it is quite possible that Augustine (or his source) would casually describe the climb from the Curiae Veteres to the arch of Titus (see Fig. 4) as an ascent of the Sacra Via, although this was technically not a part of that street. This alternative understanding is not an option one can easily dismiss, for we have seen above that Festus and Varro speak of two concurrent concepts of the Sacra Via in an earlier period.

However, even if we were to ignore these problems for the moment, and accept the note on ‘ascent and descent’, this still presents no good evidence for positing a semicircular course for the Luperci in the time of Augustine (let alone Varro). If the Luperci did in fact ascend and descend the Sacra Via and Augustine saw this himself while in Rome (which cannot be completely ruled out), this was most likely a consequence of this area being the centre of the celebration,Footnote 56 so the priests would have to spend a long time on the street and the Forum, going back and forth between the people desiring their blows. A ritual that involves running and playful striking can barely be a completely ordered event. It was more like a playful game than a solemn procession. However, this does not mean that it was completely devoid of rules, or that the course varied greatly from time to time. Granted, it is not impossible to imagine that the lustration aspect of the Lupercalia was forgotten at some point and that the changes of late antiquity also introduced a different course for the Luperci, but then one would need more to deduce such far-reaching conclusions than this ambiguous passage of Augustine. The bishop of Hippo does not say that he saw the Luperci running on the Sacra Via nor that he learnt this from Varro: both are assumptions made by modern scholars.

Thus, although Ziolkowski's cautionary note on the Lupercalia ‘obviously’ undergoing changes through time does have a general value, there is nothing to indicate that the particular course of the Luperci significantly changed.Footnote 57 No matter how strange this might seem to some modern scholars, it is fully in line with the conservative nature of Roman public ritual. Otherwise, how does one explain that Varro's note at the end of the Republic points to the lustration of the ‘ancient’ Palatine pomerium (which indicates the regal period)? Naturally, various aspects of the Lupercalia did undergo changes through the centuries of the empire, but when it comes to the course of the ritual Augustine's information need not be in contradiction to the Republican sources.Footnote 58 In fact, a note in the fifth-century calendar of Polemius Silvius still explains the month of February as dictus a febro verbo, quod purgamentum veteres nominabant quia tum Romae moenia lustrabantur. Footnote 59 This is still in tune with Varro and might even be directly or indirectly derived from him. The walls of the city of Rome in the fifth century went far from the ancient pomerium, so Polemius can only be referring to the walls of the city in the much older sense (the walls around the Palatine) while the festival implied in febro can only be the Lupercalia.Footnote 60 Can we then reconstruct a route for the Luperci that would at least be a typical model, if not a fixed course they strictly adhered to through the long centuries of the ritual's performance?

In the most perceptive of the discussions on the issue, Coarelli (Reference Coarelli and Greco2005: 34–6) also recognized Varro as the most authoritative and explicit source, and consequently reconstructed the course as encircling the Palatine anticlockwise. Thus, the Luperci started from the Lupercal, ran along the Circus Maximus, then passed though the valley between the Palatine and the Caelian hill in the east (what is now Via di San Gregorio), before reaching the Sacra Via and the Forum. We cannot know whether they entered the Sacra Via at the Compitum Acilii and then proceeded the same way as the augurs did (according to Festus and Varro) or simply cut short to the summa Sacra Via ascending from the Curiae Veteres. In other words, the question is whether they passed the entire length of the Sacra Via in its longer version, or simply its shorter version, the Sacra Via in the popular sense. Coarelli (Reference Coarelli and Greco2005: 36) suggests the former option, but does not insist on it. Both options were viable until the fire under Nero and subsequent rebuilding, but after that the Luperci could no longer take the route from the Compitum Acilii, but would have to reach the summa Sacra Via ascending from the Curiae Veteres (see map, Fig. 4). In my view, this was a minor change in the context of the Palatine. What is important is that they had to encircle the Palatine in order for this to be a proper lustration, and that this is what Varro and Plutarch both attest.

Another possible piece of comparative evidence is the Lupercalia in Constantinople, usually ignored in the modern scholarship. Granted that the ritual was radically changed to suit the Christian capital (see now Graf, Reference Graf2015: 175–83), it is interesting to note that it took the form of a circular course in the Hippodrome. Munzi argues that this (like many other topographical elements in the new capital) was modelled on the Roman performance of the rite: it takes account of the fact that the Luperci ran a circular course, but also that they started at the Lupercal (which Servius places in Circo) and proceeded along the Circus (equivalent of the Hippodrome) a great part of the way (Munzi, Reference Munzi1994: 347–64).Footnote 61 In other words, if the Byzantine descendant of the Lupercalia can be used at all, it can only be adduced as additional evidence for the circular course of the Luperci in fourth-century Rome.

Reconstructing the course of the Luperci around the Palatine in an anticlockwise direction makes sense of all the facts at our disposal: they start the lustration at the Lupercal, run along the Circus and east of the Palatine up to the Sacra Via which gives access to the Forum. The people familiar with the fact would wait for them all around the hill, but especially in the last two places. The Forum features prominently in the description of the celebration in 44 bc,Footnote 62 and a fig tree was planted there in front of the statue of Silvanus. Although the antiquity of Tacitus’ precise delineation of the Palatine pomerium is debatable, there can be no doubt that the original pomerium went around the Palatine.Footnote 63 Thus, the wider area of the Forum was most probably visited by the Luperci in the celebrations that preceded the time when this became the centre of the city, which is archaeologically dated to the seventh century bc.Footnote 64

We have thus followed our Luperci as far as the Forum. The question that naturally arises is whether they stopped here and simply dispersed or returned to the Lupercal. Again, as the rite was a lustratio, it would require them to follow through with the circumambulation, and return to the place from which they had started. Coarelli has the priests go anticlockwise, as is typical of lustrations, but he does not give examples.Footnote 65 The direction of lustration is best illustrated on Trajan's Column, where three panels all clearly represent a lustration of the army going anticlockwise.Footnote 66 The same direction is taken in other rites that involve circumambulation. Tacitus refers the origins of the Palatine pomerium back to the mythical founding of Romulus, who ploughed the furrow starting from the Forum Boarium and proceeding anticlockwise to the Forum.Footnote 67 This ritual was in fact performed at the founding of Roman colonies to mark the pomerium of a new city.Footnote 68 The mausolea of both Augustus and Hadrian had annular corridors that rose in an anticlockwise direction towards the burial chamber. As Davies argues (Reference Davies2000: 124–7), this was not intended for construction purposes, but conveyed a religious idea: the visitor circled the tomb in an anticlockwise direction, in effect repeating the act of decursio that accompanied the burial. It is significant that Statius refers to decursio with the verb lustrare: lustrant ex more sinistro orbe rogum.Footnote 69 The equation clearly implies the two rites took the same direction. All this indicates that the anticlockwise direction of lustration would also be taken by the running Luperci.

To conclude, there are several reasons to believe that the course of the Luperci was not arbitrary, even if it was not completely fixed and immutable through the ages. The first is our sources’ insistence on the connection to the Lupercal and other specific locations around the Palatine, the Forum and Sacra Via. The second is the use of the technical term lustrare by Varro, his and Plutarch's description of the ritual, and the connection to the Palatine pomerium. The ancient sources always interpret lustration as a ritual that takes a circular course, and the available evidence would indicate that it proceeded in an anticlockwise fashion. Although modern scholars take Augustine's statement on the Lupercalia as a citation of Varro, there is very little to support this hypothesis as the whole passage is fraught with a biased interpretatio Christiana. On this view, the Lupercal would be both the start and end point of the course. The cave is not to be identified with the grotto discovered in 2007, but its remains may be located in the south portion of the triangle enclosed by Scalae Caci in the east, the temple of Magna Mater in the north and Vicus Tuscus in the west, most likely close to the present church of St Anastasia and not far from the Circus Maximus.

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result of several years of intermittent research in Rome and Oxford. It started as a thesis chapter, and was considerably improved during my stay at the British School at Rome as a graduate student on the City of Rome course 2013. Funding for this was provided by the University of Oxford Clarendon Fund, Merton College and the Craven Fund of the Faculty of Classics. Access to ancient sites (arranged by the BSR, and granted by the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma) and a guided tour of the surrounding area completely transformed my perspective on Roman topography. Conversations with other participants, especially with the course director Robert Coates-Stephens, were very helpful in this respect. My supervisors, Stephen Heyworth and Anna Clark, read the paper at various stages and were instrumental in its formation. Nicholas Purcell and Christopher Pelling offered useful comments, as did Christopher Smith and Matthew Robinson, who acted as my thesis examiners. Finally, the Craven Fund again provided funding for a research stay at the American Academy in Rome in July 2016 so that I could transform the thesis chapter into a journal article. The hospitality of the American Academy and the help provided by its director Kim Bowes cannot go unnoticed. Enrico Prodi kindly corrected my pidgin Italian and facilitated obtaining permissions for some of the figures. I owe a great debt of thanks to all of these scholars and institutions as I do to both Mark Bradley (as PBSR editor in 2016–17) and Alison Cooley (as editor for the current 2018 issue) and three anonymous referees. The sole responsibility for all remaining mistakes lies with the author.