In his 1992 article, ‘Today, Freedom is Unfettered in Hungary,’Footnote 1 Columbia University history professor István Deák argued that after 1989 Hungarian historical research enjoyed ‘unfettered freedom.Footnote 2 Deák gleefully listed the growing English literature on Hungarian history and hailed the ‘step-by step dismantling of the Marxist-Leninist edifice in historiography’Footnote 3 that he associated with the Institute of History at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS) under the leadership of György Ránki (1930–88).Footnote 4 In this article he argued that the dismantling of communist historiography had started well before 1989. Besides celebrating the establishment of the popular science-oriented historical journal, History (História) (founded in 1979) and new institutions such as the Európa Intézet – Europa Institute (founded in 1990) or the Central European University (CEU) (founded in 1991) as turning points in Hungarian historical research, Deák listed the emergence of the question of minorities and Transylvania; anti-Semitism and the Holocaust; as well as the 1956 revolution. It is very true that these topics were addressed by prominent members of the Hungarian democratic opposition who were publishing in samizdat publications: among them János M. Rainer, the director of the 1956 Institute after 1989, who wrote about 1956. This list of research topics implies that other topics than these listed before had been free to research and were not at all political. This logic interiorised and duplicated the logic of communist science policy and refused to acknowledge other ideological interventions, including his own, while also insisting on the ‘objectivity’ of science. Lastly, Deák concluded that ‘there exists a small possibility that the past may be rewritten again, in an ultra-conservative and xenophobic vein. This is, however, only a speculation.’Footnote 5 Twenty years later Ignác Romsics, the doyen of Hungarian historiography, re-stated Deák's claim, arguing that there are no more ideological barriers for historical research.Footnote 6 However, in his 2011 article Romsics strictly separated professional historical research as such from ‘dilettantish or propaganda-oriented interpretations of the past, which leave aside professional criteria and feed susceptible readers – and there are always many – with fraudulent and self-deceiving myths’.Footnote 7 He thereby hinted at a new threat to the historical profession posed by new and ideologically driven forces. The question of where these ‘dilettantish or propaganda-oriented’ historians are coming from has not been asked as it would pose a painful question about personal and institutional continuity. Those historians who have become the poster boys of the illiberal memory politics had not only been members of the communist party, they also received all necessary professional titles and degrees within the professional community of historians.

With the fall of the communist regime in 1989 the infrastructure of historical research was transformed.Footnote 8 New faculties of humanities were established at Miskolc University and elsewhere, within which local scholars taught alongside guest professors from Budapest often known as ‘intercity professors’. New departments were founded, such as the department of cultural history at the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) of Budapest. This looked like a new dawn for the Hungarian historical profession. However, from 2006Footnote 9, during the harmonisation of Hungarian higher education with European Union standards (the Bologna Process), higher educational programmes were transformed again. The five years of university education was divided into three years of bachelor and two years of masters’ programmes in order to establish a common framework for European educational mobility programmes. Introducing a two-year quasi vocational training after three years of basic, bachelor education was tailored to the ever-changing needs of the labour market. Small history departments, which had tried to transform Hungarian historical research, often became the losers in this process, partly because finance-focused decision makers supported mass education, and partly because their student numbers dropped.Footnote 10

The post-1989 change in institutional structures affected Hungarian historical journals as well.Footnote 11 Several new journals emerged and gained prominence. Among them Sic Itur Ad Astra, started by history students in 1987; Gesta, the journal of the University of Miskolc's Institute of History, also initiated in 1987; and Korall, a journal for social history founded by young researchers of history, sociology and anthropology in 2000. Furthermore, several specialised historical journals emerged (on history of agriculture, heraldry etc.). Because of this proliferation it became increasingly challenging to fill all these journals with high quality articles.Footnote 12 Quality assurance has always been a question as there are generally no double-blind review processes of the submitted papers. Instead, in Hungary the editor himself (as only one historical journal has a female editor in chief) comments on the articles without using a peer review process. The other side of the quality assurance is related to the ranking of the journals in the Depository of Hungarian Academic Works (MTMT). The list of ranked journals has been compiled by members of the profession and the results suggest that the journals they publish are usually on the list. Because of the criteria used to assemble the list, a popular article published in Rubicon, similar to BBC History, can be given as much credit as a twenty-five page long scholarly article that follows rigorous research conventions. Such developments suggest that the erosion of professional standards happened also from inside the profession without much external pressure.

In spite of these new methods for evaluating historical publications, the most prestigious historical journals remained those that were all already published before 1989 and were edited by mostly the same staff as before – and they obviously made it to the newly established ranking system. These are Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle), established by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), Institute of History in 1958; Centuries (Századok), established in 1867 by the Hungarian Historical Society; Aetas, established in 1985 by the University of Szeged's Institute of History; and Our Past (Múltunk), the journal of the Institute of Political History (the former Institute of Communist Party History).

From the beginning of the 2010s another factor started to influence the conditions of historical research and, consequently, historical journals. The Hungarian state created and funded new history research institutes, such as the Veritas Institute, The Committee of National Remembrance (NEB), the Clio Institute, the Research Institute and Archives for the History of Regime Change (RETÖRKI) and the Institute for Hungarian Studies. These institutes have no quality assurance as they function without adhering to generally accepted scientific standards: publishing without footnotes, hiring candidates without doctoral degrees or any track record of producing relevant published research. Their main goal is to influence public history; thus, they primarily publish online journals. However, these institutions are addressing exactly those topics which have been listed by Deák in his article in 1992. That the writing of contentious political history is increasingly being done by amateur historians suggests that those professional historians who should have benefitted from their ‘unfettered freedom’ and addressed such previously taboo topics missed their chance. This was partly due to the personal and institutional continuity across political eras visible in different institutions. It was also partly due to professional historians talking among themselves and failing to win a larger audience within broader civil society. By failing to engage with criticisms that the pre-existing academy in Hungary was out of touch, nepotistic and resistant to change, professional historians ceded ground to amateurs who were interested in capturing public attention with their politically charged writings. As a result of this missed chance it proved much easier during the past ten years for politically motivated non-historians to write popular histories that were inspired by an illiberal memory turn. As we will see, ultra-conservative and xenophobic history writing did indeed start to become normalised within mainstream historical narratives.

One reason for this development was the success of the right-wing populist FIDESZ which – in coalition with the Christian Democratic Party (Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt; KDNP) – won three consecutive elections in 2010, 2014 and 2018. During this time the Hungarian government has repeatedly intervened in the field of memory politics, even attracting international attention and condemnation when it erected Second World War monuments at night, rehabilitated controversial politicians of the interwar times, rewrote history curricula, founded increasing numbers of historical research institutions and museums in order to educate and give legitimacy to new cadres in history who supplanted the old ones and so on.Footnote 13 The party continues to be very popular inside Hungary and seems little concerned by international condemnation which, in any case, has not been followed by any meaningful sanctions.

By 2019 the ‘small possibility’ that Deák predicted and that Romsics still did not consider a potential source of danger less than ten years ago has become part of our reality. From among the institutions that represented the post-1989 ‘unfettered freedom’, the Europa Institute has ceased to exist, and the CEU has moved all degree programmes to Austria due to the Hungarian government's failure to sign the necessary documents that would ensure CEU's legal status.Footnote 14 Thus, in September 2019 CEU's freshly enrolled students started their academic studies at a new Vienna campus. Furthermore, the Hungarian government changed the structure and appointed loyal academics in the final decision-making body within the Hungarian Accreditation Committee (HAC), the most important independent institution controlling the quality of Hungarian research. On 1 September 2020 a new procedure came into force, which is stricter than the previous one.Footnote 15 It is worth noting that the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA), the most important European institution guarding quality of education, found nothing peculiar and renewed the membership of HAC in 2018. Once chancellors were given the role of managers of universities, at exactly the same time that CEU was forced out of the country, a two-year master's programme in gender studies was deleted from the accredited study list and the autonomy of universities was severely diminished. The newly established system of chancellors overwrote the previous university autonomy, and the chancellors are now making all strategic and financial decisions independent of the Senate or faculty meetings. The chancellors are appointed by the government, and thus it is not a surprise that loyal apparatchiks with zero experience with university administration obtained these positions.

In 2018 a new government decree entered into force which stipulates that any accredited university programme can be erased from the list of accredited degrees without scientific reason.Footnote 16 In addition, in 2019 the HAS was deprived of its research institutes. These were then taken over by the Hungarian state under a newly created organisation, the Eötvös Loránd Research Network (Eötvös Loránd Kutatási Hálózat). Although the precise future is unknown, it is likely that the government will begin controlling its scientific work, which can also affect the only online journal on Hungarian history in English, the Hungarian Historical Review, which was founded in 2011 by the HAS Institute of History. The popular science journal that Deák celebrated, History, has also ceased to exist, its market position is now partly covered by BBC History and partly by the conservative pro-government Rubicon. The other popular journal Newage.hu (Újkor.hu) online is a glossy magazine journal that attempts to publish high quality scientific works beside popular science articles.

The Reasons Behind the Recent Changes

In 2009 Gábor Gyáni listed three key factors that shaped the situation of historical research: the 1989 political turn, the gradual strengthening of the national framework and the effect of globalisation that led to institutional and theoretical pluralism.Footnote 17 At the same time Gyáni argued that after 1989 ‘it was still being expected [from historiography] to provide a usable past serving direct political needs’,Footnote 18 which hindered the modernisation of historical research. The passive tense used here obscures both the political actors and the inability of the profession to meet the new challenges. The academic discussions about key issues of Hungarian historiography that did take place were primarily a contest between personalities rather than methodologies.Footnote 19 In light of recent events in Hungarian politics, it is certainly true that the István Deák-envisioned ‘modernisation’ of Hungarian historical research failed to fulfill its promise with regard to changing its structure, research topics and personnel. In turn this failure to change enabled the illiberal turn.

Usually a historiographical overview analyses various methodological approaches: the history of institutions, the works of exceptional historians, the schools of historiography and the different focuses of research (economic, intellectual, social, gender, etc.). In this article, we use a different quantitative analysis: we will look at the historical journals that best reflect the achievements of Hungarian historians during the past three decades. This approach allows us to gain a greater distance from the personal conflicts and dramas within the profession and to identify broader trends that have largely been overlooked. In this first systematic analysis of the major printed historical journals we use one aspect of the (failed) democratisation of Hungarian historiography, women's participation. Our hypothesis is that the idea of ‘unfettered freedom’ celebrated by Deák was not accessible to everybody. Women were excluded from the historical profession as it was an ‘old-boy’ or ‘golden boy’ network and that prepared the way for the populist ‘her-story’ turn. We must add that the remasculinisation of history writing after 1989 also brought along self-censorship among authors as a personal and professional survival strategy. For historians who have had to compete for meagre and decreasing state funding in a non-transparent and over-politicised environment, unquestionable loyalty and conflict avoidance have often seemed to be the most successful professional strategies.

The article has two aims. Based on the analysis of the articles published in the most significant Hungarian historical journals, it will examine whether Gábor Gyáni's statement, that mainstream political history is still dominating Hungarian historiography, remains valid.Footnote 20 Relatedly, we will also scrutinise the way in which, despite ‘unfettered freedom’, institutional pluralism and globalisation, research topics, structures and personnel have remained more or less unchanged between 1989 and 2017. This, in our view, has prepared the grounds for the recent illiberal memory turn as illiberal revisionist historians are not only ‘doing nationalism’ much better but also stepped out from the ivory tower and gained much popular support.

The second part of the article is concerned with the claims presented by what has been by far the most comprehensive article on developments of post-1990 Hungarian historiography. In their 2007 piece, Balázs Trencsényi and Péter Apor made three claims about the evolution of Hungarian historical research. The first was that a new generation of historians emerged who primarily focused on social history using ‘Western’ methods.Footnote 21 This new generation studied mostly at CEU and benefitted from the partial tuition waiver, international connections and projects there. With CEU moving to the very expensive Vienna this opportunity is over. Their second claim was reminiscent of Gábor Gyáni's previous statement that Hungarian historiography has versatile subcultures vulnerable to political aspirations. They argue ‘plurality might well lead to the formation of mutually exclusive sub-cultures, based on specific internal norms of selection and vehement emotions towards “insiders”, who seem to possess the truth, and towards the “uninitiated”, who are at best “uninterested” or right away “inimical”’.Footnote 22 Their third claim was that the ‘objectivist conviction’ and the ‘guild perspective’ of historians remained unchanged.Footnote 23 As Apor and Trencsényi claim, due to the unchangeable character and institutional framework of Hungarian history writing this new generation of historians failed to initiate major change in the structure and topics of Hungarian history writing. This also contributed to the sclerotic state which made infrastructure vulnerable to the illiberal takeover. The article uses a mix of both qualitative and quantitative analysis to analyse the evaluation of Hungarian historiography of the past decades.

Inspired by their analysis, this article will examine the factors that contributed to the dismantling of Hungarian historiography's versatile subcultures and explain why the guild members are still primarily men. The article argues that the unchanging composition of the ‘guild’ of historians contributed to the illiberal turn as Hungarian historiography resisted any meaningful change.

During the past decade the Hungarian state has divested enormous funds from higher education and scientific research, which has decreased the number of students and impoverished critical thinkers, forcing some of them to leave their fields of expertise. At the same time, since 2010 the Fidesz-Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP) government has set up a novel state formation and a new quality of governance. Political scientists still argue whether the current ruling system should be defined as ‘democratic authoritarianism’, an ‘illiberal state’ or ‘mafia state’. Polish sociologist Weronika Grzebalska and Andrea Pető suggested the term ‘polypore state’.Footnote 24 Polypore is a parasite pore fungus that lives on wood and produces nothing else but further polypores, while concomitantly changing the structure of the tree in order to monopolise its resources. In their article, Grzebalska and Pető defined three functional characteristics of the polypore state, all of them central to the illiberal memory turn. One typical feature of the polypore state is the establishment of a parallel, state financed, research institutes-NGO sphere that exists without quality assurances, including the aforementioned new state funded history research institutes. Another typical feature of the polypore state is the ‘women's history or herstory turn’. Many young women were hired in key positions at the price of a conformist attitude and an avoidance of controversial or problematic research topics. The presence of these token women makes the usual criticism of demanding more female presence obsolete. It also frustrates calls for a deeper understanding of the roots of the problem, namely that the post 1989 period did not deliver promised equality to women. In the second section, this article will illustrate this argument in the case of the historians’ profession, showing that female historians have been marginalised. Lastly, the third characteristic of the polypore state globally is its ubiquitous usage of the security discourse born after 9/11 and then adopted globally. Every policy related question becomes framed as a security question, even the issue of memory politics. Accordingly, those who represent an alternative standpoint may quickly remain without funds and may experience personal attacks as well. In the illiberal state, ideology is substituted by battles over memory politics. As the triple crisis (security, financial and migration) caused uncertainties, those political forces convincingly offering stability and security have been gaining momentum. Not taking any risk in choosing topics of research can contribute to a successful professional life strategy and lead to an amplification of the traditional fields of research like political, diplomatic and military history.

After 1989 the newly independent states of the former communist bloc based their legitimacy on nationalism and anti-communism. Maintaining and cultivating both requires active memory politics. Therefore, the symbolic importance of, and state funding channeled into, historical research have increased. The symbolic topics, mentioned in István Deák's article in the opening of this article remained the same: the consequences of 1918, the Holocaust and 1956.

The Database

We examined seven peer reviewed historical journals: Aetas, Gesta, Korall, Our Past (Múltunk), Sic Itur Astra, Centuries (Századok) and Historical Overview (Történelmi szemle). These journals are the most important representative forums of Hungarian historical research for mapping the last three decades of Hungarian historiography as they represent all the institutes of history within universities together with major research institutions. Their profile is general history and specialised journals, such as those focusing on heraldics or urbanisation, are not a part of the sample. Also, scholarly articles covering historical topics which were published in non-historical journals outside the sample are not counted. This distortion does not fundamentally influence the general tendencies emerging from the sample, however. These journals primarily publish articles by Hungarian scholars and therefore allow us to examine current trends in research conducted in Hungary. We examined the period from the change of the regime (1990) until 2017.Footnote 25 Our database contains each issue of each journal from the given period, altogether 557 issues. We have not included HHR as its readers are outside Hungary, nor have we considered popular journals.

The Aetas journal for historical research, founded in 1985, published three to four issues annually in the examined period, with the exception of 1990 when only two issues were published. Based at the University of Szeged, it mostly publishes works by historians employed by institutions in the provinces, not in Budapest. According to the journal's self-introduction, besides publications on political history, the journal aims to represent novel research on cultural, economic and social history, as well as on intellectual history. Footnote 26

Gesta, the online journal of the Institute for History of the University of Miskolc, was first published in 1997. Between 2000 and 2003 the periodical had no issues, in every other year it published one issue, except for 2006, when it published two issues.

The Korall Journal for Social History was established in 2000 in Budapest. At the beginning it had two to three issues, and since 2008 it increased the number of published issues to four. According to its self-definition ‘the Korall Journal for Social History aims to provide a platform for Hungarian and international research, which develops novel approaches, explores and undertakes interdisciplinary social study, analyses the historical processes and connections underlying social, economic and political phenomena’.Footnote 27

Our Past (Múltunk) is a ‘journal of modern and contemporary history, with a focus on the political history of the 20th century, [which also aims to] give place to essays of social history and the history of ideas’.Footnote 28 The journal was originally titled Political History Publications, and it was the official journal of the Institute of Party History of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Hungary in Budapest.Footnote 29 From 1989 onward it was published with renewed contents and title. Until 2002 three to four issues were published per year, since 2003 uniformly four.

Junior history scholars founded Sic Itur Ad Astra in 1987 in order to ‘offer publication opportunities to grad and postgrad students. . . . The periodical gives place to publications from all walks of historical research’.Footnote 30 Between 1987 and 1996 it published one or two issues each year, then, after a two year-long break, it published two to three issues annually from 1999 until 2006. After 2006 one issue was published per year on average, except for 2007, 2010, 2012 and 2014 when no issues were published. 2009 was a different kind of exception: that year Sic Itur Ad Astra published three issues.

Centuries (Századok), established by the then brand new Hungarian Historical Society in 1867, has the longest tradition among Hungarian historical journals. From its beginnings it aimed at offering an overview of the state-of-the-art of Hungarian historiography.Footnote 31 The periodical came out each year during the examined period: between 1990 and 1993 with three to four, in 1995 with five and since then with six issues annually. The most conservative and mainstream journal, it primarily publishes on traditional topics such as political and economic history.

The Historical Overview (Történelmi szemle), launched in 1958, is the periodical of the Institute of History of the HAS Research Centre for the Humanities in Budapest.Footnote 32 The published papers are mostly authored by the staff of the institute and encompass a wide time spectrum as, while the journal focuses on modern and late-modern history, it frequently gives place to research on the medieval ages as well.Footnote 33 The Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle) published two issues annually till 2006 (exceptions: four issues in 1995, three in 1996 and 1997) and uniformly four issues since 2007.

As it is apparent, some of the examined journals lacked continuity for financial or personal reasons; nevertheless, the published issues fairly represent Hungarian historical research as all major historical journals are considered in the long durée analysis covering the full spectrum of Hungarian historical journals.

The Thematic Composition of Publications

We divided the publications into two main groups: original scientific papers and book reviews. First, we will focus on the papers. The seven journals in the examined period published altogether 3,038 original scientific papers, on average 5.5 per issue. Our Past (Múltunk) (4.0), Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle) (4.3) and Gesta (4.4) published somewhat less, while Aetas (5.7), Korall (7.3) and Sic Itur Ad Astra (7.8) published somewhat more original scientific papers than the average.

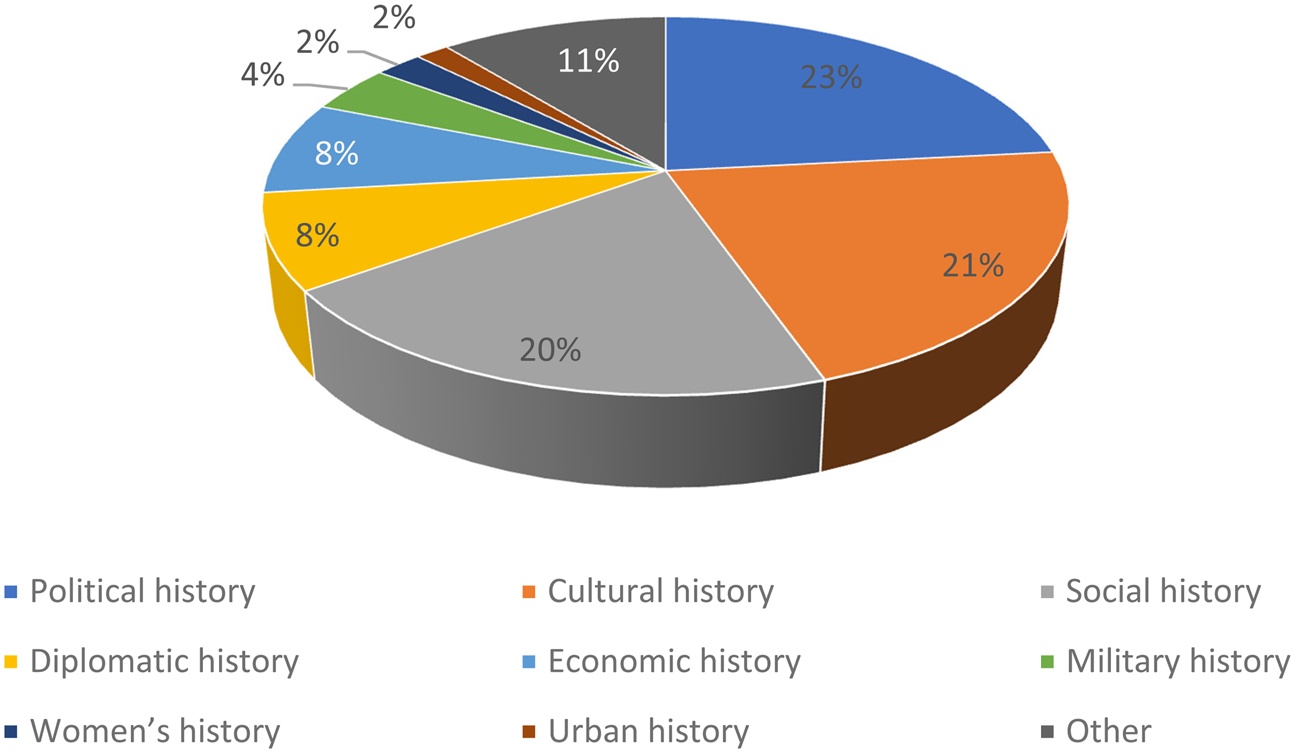

Figure 1 shows that, during the examined period, most papers were on political history (23 per cent), cultural history (21 per cent) and social history (20 per cent), while papers on diplomatic history and economic history represented close to 10 per cent of all publications. The proportion of publications on military history (4 per cent), women's history (2 per cent) and urban history (1 per cent) was extremely low.

Figure 1. Thematic Composition of Publications (1990–2017)Footnote 34

Among the journals, the thematic composition of Aetas, Centuries (Századok) and the Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle) was closest to the average. This is not surprising as Centuries (Századok) and Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle) have general profiles. Gesta published a higher than average proportion of social history papers (35 per cent), while Korall had social history (36 per cent) and urban history (7 per cent) papers in a higher than average proportion. 50 per cent of the papers published in Our Past (Múltunk) were on political history, which is significantly higher than the average of 26 per cent. In Sic Itur Ad Astra we found a higher than average presence of cultural history research (37 per cent).

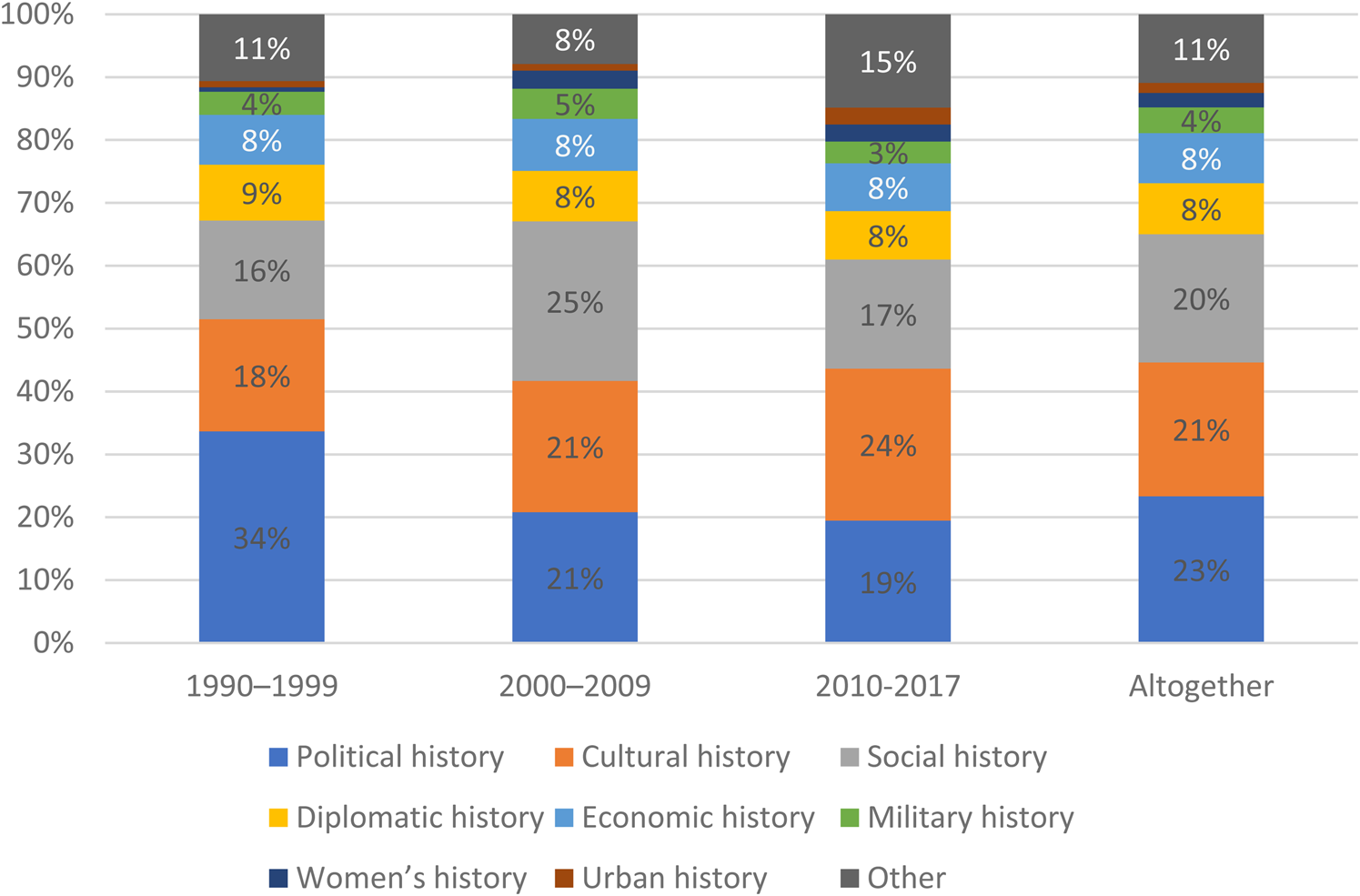

Although the thematic structure of the journals followed more or less their profiles, it was more important to analyse the temporal changes or rather non-changes (Figure 2). When designating sub-periods, besides historical characteristics, we also took methodological concerns into consideration. For example it was important to have enough articles in each period. As a result, we have designated three sub-periods: 1990–9, 2000–10 and 2010–7. The first period, 1990–9, is an intermediate period as historical research requires time. Most of the articles published had been conceptualised years before. The second phase included the EU accession in 2004. This is also the period of the Bologna process which, as argued before, contributed not only to the increasing teaching load of historians working at universities but also had the effect that salaries were cut. The third phase from 2010 marks the beginning of illiberal cultural politics.

Figure 2. Thematic Composition of Publications (1990–2017)Footnote 35

The most remarkable change is that after 2000 there was a significant drop in the proportion of publications on political history. As a hypothesis to explain this process we suggest that it is due to a further de-politicisation of mainstream history writing. While between 1990 and 1999 little more than a third (34 per cent) of all original scientific papers were on political history, during the latter two periods their proportion was around one-fifth. We also found that the proportion of social history papers increased between 2000 and 2009, and the proportion of cultural history papers also increased after 2010.

Gender Composition of Publications

Women authored 25 per cent of all original scientific papers; men authored 75 per cent. To see whether women are underrepresented among the authors, we used two sets of data as a basis for comparison: (1) the gender composition of university students majoring in history on MA and PhD levelsFootnote 36 and (2) the gender composition of Hungarian historians.

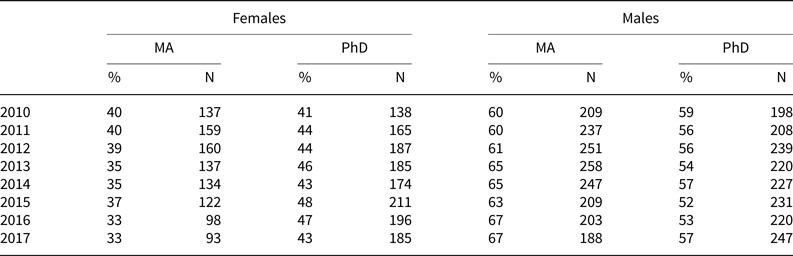

In the case of university students, we used data after 2010 since this is the year from which students majoring in history on both MA and PhD levels graduated in the new system set up according to the Bologna process.Footnote 37 Table 1 shows that the proportion of female MA history students was 40 per cent in 2010 and it gradually decreased to 33 per cent in 2017. This coincided with the remasculinisation of history writing and the disappearance of women from the higher ranks of the profession. However, the case of PhD students is different, as the proportion of females among them ranged between 41 and 48 per cent with no particular trend.

Table 1. Gender Composition of MA and PhD Students Majoring in History (2010–2017)

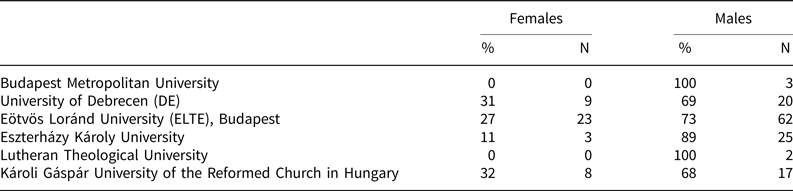

Since the number of currently active Hungarian female historians is unknown, we need to rely on indirect indicators, such as the gender composition of history researchers at the HAS Institute of History and the gender composition of historians employed at Hungarian universities’ history departments. In the case of the HAS we dealt with the average for the period of 2010‒5, and in the latter case with data from 2018 (Table 2).

Table 2. Gender Composition of Historians at University History Departments in 2018

Between 2010–5 the proportion of female historians in the HAS was 26 per cent on average, and in 2018 at Hungarian university departments the proportion of employed female historians was also 26 per cent. It is striking that, although 33 per cent of MA and 43 per cent of PhD students majoring in history were females, the proportion of female historians employed in the above institutions was only 26 percent.

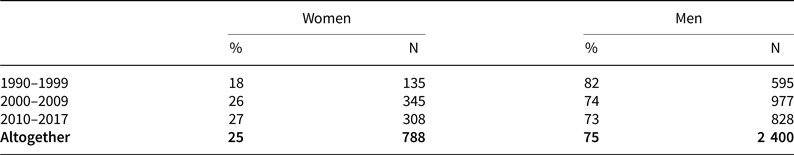

During the examined time period the average proportion of female authors of scientific papers in Hungarian historical journals was 25 per cent. Table 3 shows an increasing trend from the period of 1990–90 when the proportion was only 18 per cent to the period after 2010 when it increased to 27 per cent. Although this is not significantly lower than the proportion of female historians employed in the HAS and at Hungarian universities, it is indeed significantly lower than the proportion of female history students at MA, and especially PhD level.

Table 3. Gender Composition of Authors During the Sub-Periods (1990–2017)

The argument that women are just not interested in political or military history narrows down the structural factors, institutional practices and hierarchies to individual choices.Footnote 38 It is by no means a surprise that there was a high proportion of women (74 per cent) among the authors of papers on women's history. There was a higher than average proportion of women among the authors of cultural history papers as well (30 per cent versus 23 per cent). The proportion of male authors was higher than the average 77 per cent among the authors of diplomacy history (83 per cent), political history (84 per cent) and military history (89 per cent).

The journals Korall (29 per cent) and Sic Itur Ad Astra (37 per cent) published somewhat more female authors than average, while the flagship journal of Hungarian historiography, Centuries (Századok) published more men (80 per cent). The Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle), a journal of the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, has been always more embedded in international trends and novel approaches, as this was the official journal of the research institute praised by István Deák in his article quoted at the beginning of this article. The Institute of History served as a collection point for those historians after 1956. The exclusion of women necessarily led to the isolation and vulnerability of the profession to populist challenges as it narrowed down its potential popular basis.

Book Reviews

During the data collection we separated out book reviews when collecting data because this shows the international embeddedness of historians: what kind of books do they find important to introduce to the Hungarian audience and who has the biggest negotiative power to have the review published. We also separated the authors of reviewed works and the authors of book reviews. During the examined time period altogether 2,784 book reviews were published, on average five per journal issue. However, in this regard there were significant differences between the journals: Historical Overview (Történelmi Szemle) published almost no book reviews (average: 0.2), and a relatively small amount of book reviews was published in Sic Itur Ad Astra (1.6), Gesta (2.2) and Our Past (Múltunk) (3.5). Centuries (Századok), by contrast, published significantly more than the average number of book reviews per issue (9.3).

19 per cent of the reviewed books were authored by women and 81 per cent by men. When compared to the gender composition of the authors of original scientific papers (25 per cent and 75 per cent for females and males, respectively), one can see that on average there were more men and fewer women among the authors of reviewed books than that of the original scientific papers. However, the gender composition of the authors of the reviews is very similar to that of the authors of original scientific papers, as 23 per cent of them were female and 77 per cent male.

Regarding the temporal changes, we observed the same pattern as in the case of the authors of original scientific papers: though no linear tendency was discernible, still, between 1990‒9 the proportion of men among the authors was higher than the average of the examined time period, and after 2010 the proportion of female authors was higher than the average, being close to the proportion of scientific papers authored by females.

There were some marked differences between the individual journals in this regard, too. Sic Itur Ad Astra, the only journal with a woman editor-in-chief, was also the only journal which had a much higher than average number of women among the authors of scientific papers as well as among the authors of reviewed books and among book review writers. 41 per cent of the reviewed books was authored by women (19 per cent was the average of all journals), and 40 per cent of the book reviews was written by women (23 per cent was the all-round average). Korall, the journal with the most women among its editors, also published a higher than average proportion of woman-authored texts, primarily book reviews (33 per cent of women among the authors). In the case of Gesta the difference is even more marked: 26 per cent of the authors of the reviewed books were women, as well as more than half (55 per cent) of book reviewers.

Conclusions

The concluding section starts with some anecdotal evidence. When we started our careers at the end of the 1980s reading rooms of the archives were filled with more women than men. Nowadays it is exceptional to see a young woman working in the archives. Achievements of the ‘statist feminist’ period in women's employment have been withered away by the neoliberalisation of Hungary. The importance of history writing in creating the required legitimacy for the new, independent nation state, together with moving women from the labour market to the grey economy and unpaid care work, contributed to the increasing gender inequalities.Footnote 39 The historical profession is not different from other professions as generally fewer and fewer women are crushing the glass ceiling and remain employed in professions behind the glass wall.Footnote 40 Our data also proves that no significant transformation took place in Hungarian historical research's thematic or gender composition between 1990 and 2017. Although Ignác Romsics in 2011 held that most Hungarian historians are characterised by ‘value-free or value-neutral empiricism and professionalism’,Footnote 41 the ‘guild’ that Trencsényi-Apor mentioned remained omnipotent: no matter the research topic, men still dominate the field. Women's history has been the only exception, which is why woman historians are hit so hard by recent political developments: for instance, the banning of gender studies MA in 2018, and the aforementioned ‘women's history turn’, which meant that women researchers were replaced by research on women. Besides, an increase in the number of woman researchers or of scientific papers in women's studies will not necessarily bring along critical thinking about women's former invisibility and distance from decision making positions.Footnote 42 Sooner or later the ‘guild’ of Hungarian historians should ask itself what their responsibility was in not only wasting ‘unfettered freedom’ but also not foreseeing the attack on science by the illiberal polypore state.

Acknowledgements

We thank Borbála Klacsmann for her help with data collection.