Introduction

Effective psychological treatment is grounded within theories that are based on evidence, both in relation to outcomes and practice. However, good quality evidence is less evident in the literature when the clinical issues are complex, and involve a range of problems. This is particularly true of treatment in secure psychiatric services, where patients present with not only complex mental states but also antisocial offending behaviour (Perkins, Reference Perkins, Bartlett and McGauley2010; Seeler et al., Reference Seeler, Freeman, DiGiuseppe, Mitchell, Tafrate and Mitchell2014). In this paper, we explore how cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) therapists in secure hospitals address this complexity, and create therapeutic alliances with those referred to them.

Work as a therapist in a high secure hospital (HSH) is challenging for reasons that relate to both the patients and the work environment. Patient factors include high-risk behaviours, often impulsive and extreme, and complex diagnoses that include co-morbid mental illness and personality disturbance. Environmental factors include policies and procedures that constrain opportunities in the ‘treating’ environment but which are essential for containment. Patients often alternate between presenting as threatening aggressors or as vulnerable adults, with histories of victimization that have been profoundly shaping of their identity and interpersonal coping style and attitudes. Perkins (Reference Perkins, Bartlett and McGauley2010) notes the setting expectation that psychological therapies will attend to the ‘complex interactions’ that link a patient's mental state to their offending behaviour with the aim of reducing future harm.

Psychological therapy services for mentally disordered offenders therefore include interventions for both psychopathology and risk reduction. Secure mental health services offer a range of options for offenders that target criminogenic needs and relapse prevention (Perkins, Reference Perkins, Bartlett and McGauley2010). Therapeutic programmes include CBT, both individual and in groups; and may focus on offending behaviour or psychological distress.

A number of meta-analyses report the positive effects of CBT on the recidivism of offenders (Lipsey et al., Reference Lipsey, Chapman and Landenberger2001; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Lipton, Cleland and Yee2002; Landenberger and Lipsey, Reference Landenberger and Lipsey2005; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Bouffard and MacKenzie2005; Lipsey and Landenberger, Reference Lipsey, Landenberger, Welsh and Farrington2006). However, these studies have been based in prisons and not in secure psychiatric services (Perkins, Reference Perkins, Bartlett and McGauley2010) and there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of CBT with mentally disordered offenders; research on the effectiveness of psychotherapy, whichever specific model, would be of value to clinicians in practice (McGauley, Reference McGauley, Bartlett and McGauley2010).

The aim of this study was to describe the challenges and possible responses for CBT therapists of working with offenders who have (a) complex mental health needs and (b) pose a risk to others, including the clinician.

Method

Design

A qualitative research design was employed as it brings focus to individual meaning, and takes into consideration the complexity of the phenomena (Creswell, Reference Creswell2009) and unique context (Creswell, Reference Creswell1998).

Sample and recruitment of participants

The study took place in a HSH that employs a range of trained and supervised psychological therapists to offer interventions including CBT to male patients with histories of high risk violence and severe psychopathology. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling strategy. Key criteria included being in post as a chartered psychologist or accredited CBT therapist, or a qualified nurse, and holding a caseload of referrals for CBT interventions. A sample of six was considered sufficient for in-depth interviews (Smith and Eatough, Reference Smith, Eatough, Breakwell, Hammond, Fife-Schaw and Smith2006). All six participants were female and are described in Table 1. Pseudonyms have been used throughout to preserve anonymity.

Table 1. Participant information

Procedures and data generation

Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and were sent an information sheet to read before the interview. A detailed face-to-face, semi-structured interview was selected as means of data generation. A pilot interview was conducted prior to the research interviews, and this participant was asked to give feedback on the questions, the content and any ethical dimensions of the interview. No amendments were identified so data from the pilot interview were included.

The interview was based on the researcher's previous experience and focused on the experience of delivering CBT in a HSH. Specific questions were asked about challenges in CBT delivery and how they had managed these.

Analytic strategy

Each interview was audio-recorded, lasted between 45 and 70 minutes and was then transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clark, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), was used to analyse the data because of its focus on themes (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Kellehear and Gliksman1997). Analysis involved four stages as described by Braun and Clark (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The researcher (who also carried out the interviews) familiarized herself with the data by reading the text several times. The second step recorded connections between interviews, associations, preliminary interpretations, and generating initial codes; followed by identifying emerging themes. The themes were reviewed by checking them against each other and back to the original data set; and then named and defined. The final step involved ordering the themes to identify superordinate themes and subthemes.

Findings

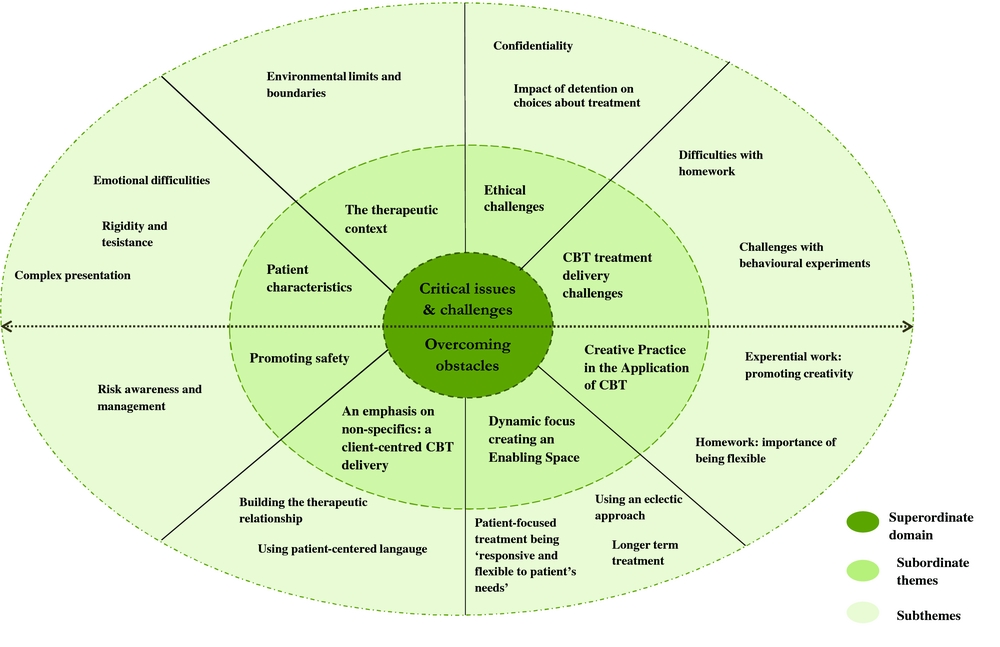

Figure 1 summarizes the themes from the interviews.

Figure 1. Thematic map illustrating the superordinate theme (in the middle), subordinate themes (clustered around the superordinate domain) and subthemes (clustered around the outer part of the figure).

Clinical issues and professional challenges

An initial theme related to aspects of clinical work with highly complex patients in a secure setting. The clinical problems described illustrate the complex and severe nature of the patient's clinical problems. The subthemes generated were ‘complex presentation’, ‘emotional difficulties’ and ‘rigidity and resistance’.

Complex presentation

All the participants described the complexities of the patient's presentation and different factors were described to emphasize the difficulties that are often a feature of the practitioner's daily clinical work.

Co-morbidity and the nature of the symptoms

The patient's presentation entailed ‘multitudes of problem behaviours’ (Laura) as ‘there is no single diagnosis here. We don't have people who come here with one problem’ (Ruth). Laura added that the primary focus may be difficult to establish as ‘it's very difficult to keep focus on one and if you want to keep treatment that is holistic’. Also, Laura described the nature of the presenting problem(s) as it relates to mental health symptoms: ‘he is paranoid, he wouldn't really talk to people’, and ‘so riddled with negative symptoms that you could ask him any questions and you would get monosyllabic answers’ and ‘he has a lot of residual symptoms which makes his thoughts quite jumbled and his word processing is quite, I think, confused’.

The effects of medication

. . .the side effects of their medication, they are really terribly drowsy and they keep on falling asleep and how much can you do then? Or they are so troubled by the side-effects like twitches and jiggles that they can't actually sit still (Ruth).

Emotional difficulties

The practitioners described how emotional suppression and avoidance of emotion can become habitual: ‘he spent so many years suppressing these feelings, not getting in touch with them. That's been his job, to suppress and not get in touch with them, so that actually to label and recognize feelings is a difficult task’ (Laura).

Some participants described how patients have often learnt unhelpful strategies for dealing with strong feelings, and how this may remind them of some very dangerous memories. Furthermore, fears about how strong emotion could possibly be handled safely seemed frequently reinforced in the wider environment, thereby promoting avoidance. An additional consequence of this was secondary/related trust issues: ‘predominantly they have been told don't talk about your emotions. If you talk about your emotions you're weak. So it sometimes takes quite a lot for them to be able to trust to talk’ (Jo).

Rigidity and resistance

Another challenge presented was the lack of intrinsic motivation to engage in treatment and a high resistance to change:

I was working with someone who had agoraphobia . . . he had difficulty coming out of his room to the point of when there was a fire evacuation and he refused to leave because of his fears of being assaulted and concerns about being harmed by other people. (Maria).

Maria described how beliefs can become inflexible, rigid and difficult to change. She reflected on her work with an individual who had become so invested in living by this belief system and its connection for him to self-preservation, and how the basis of this was highlighted in his past experience: ‘people have said in the past without them I wouldn't have nothing to protect myself if I didn't have these beliefs other people would take advantage of me’.

The therapeutic context

Environmental limits and boundaries

Participants reported their experience of the hospital procedures and security boundaries which provides an effective way of managing violence. However, the participants noted that these measures also impacted on treatment delivery. Ward staff have to take immediate action to make themselves, others, and the patient safe. In particular where behaviour is assessed as potentially dangerous to others the patient may be held for a time away from others. Chantelle described how she had adapted treatment to this situation:

Patients are often in seclusion on high dependency; seclusion does not stop therapy . . . so we negotiated the decision of him coming out, or sitting just inside the seclusion room and talking through the door.

Another clinician described switching to another model for those whose mental state was too disturbed:

. . . people who are that unwell I wouldn't be trying to do CBT with. They need more supportive therapy (Laura).

Ethical challenges

Confidentiality

Maintaining confidentiality is evidently influenced by the context of the hospital and the practitioners’ professional code of conduct. Laura acknowledged that she shares information with the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) to support the patient ‘if there is a particular risk or a particular problem . . . it's a need to know basis’. Furthermore, Chantelle highlighted that it is essential to preserve the boundaries about information sharing as this has particular meaning in forensic work:

. . . boundaries make the patient feel safe and secure. To make them feel that they have a therapist they can trust, that can be reliable, that confidentiality can be kept . . . matters so much more in here.

Furthermore, Jo emphasized the importance of having an initial conversation on the limitations of confidentiality, early on during the treatment and the need for two-way communication of expectations on this issue:

So whilst things that are said in treatment are confidential, you have to be very clear that if anything is bought up that I feel is a risk then I will discuss that with them, and that then, that needs to be taken out to the clinical team . . .

Impact of detention on choices about treatment

All the participants emphasized that most of the patients in secure care are detained against their own will, and they might experience being ‘coerced’, ‘bullied’ and ‘really anxious about coming into treatment’ (Ruth). Consequently, Maria highlighted that it is the responsibility of therapists to offer to engage patients in treatment, even during times when the patient may not understand this, or reject offers of help altogether:

. . . people are forced to do treatment rather than wanting to, and actually, do we leave them or do we encourage them to engage? (Maria).

CBT treatment delivery challenges

Difficulties with ‘homework’ (when home is hospital)

The participants reported that there are various reasons behind patients’ disinterest or difficulty in working between sessions, including being ‘paranoid about writing, maybe . . . they are illiterate’ (Maria), ‘sometimes they don't understand fully, sometimes their mental state isn't sufficiently focused’ (Ruth). Other patients may not have easy access to writing materials, thus some of the participants stated that they were often ‘reluctant’ to set homework that was about words (Ruth), but could be adapted into other scenarios (e.g. one therapist had sponsored and supported lyric-writing instead).

Challenges with behavioural experiments

The practitioners agreed unequivocally that the high security environment impacted on the opportunities for behavioural experiments: ‘I could possibly do more even in this environment, but that's quite tricky to do because of the environment and lack of opportunities’ (Laura). Others reported that working with ward staff, although so helpful if it can be organized, requires detailed planning due to competing priorities.

Perhaps as a consequence misunderstandings from ward staff (who may be taken by surprise) about patients trying out new behaviours can often emerge:

behaviour experiments [are] very limited . . . you have to be very thoughtful. I'm very creative about what behavioural experiments I do in here and then the support from some of the staff. So what I said earlier about trying assertive scripts can become: ‘Oh, you're being aggressive’. So having time to share work with colleagues that are supporting the patients is hard because we are all under time constraints . . . because ideally you would work with a primary nurse to say this is what I'm doing. These are some of the strategies. Can you support him? (Jo).

Laura also reported that the patients’ personal/life history may impact on their capacity to trust others consistently: ‘A lot of people in here who had very severe abuse, neglect type history and it can take a very long time for those people to gain that trust’.

Overcoming obstacles

All the participants offered reflections on how they work through the critical issues that are presented in practice.

Creative practice in the application of CBT

Homework: the importance of being flexible

The interviews revealed the participants’ understanding of the therapeutic procedures and the attentiveness to the clients’ needs:

You have to be flexible in that and adapt the way in which you do that in order to ensure the work is done but not to be so rigid that if they don't do it, then they don't continue with therapy (Laura).

Maria reported that she responded by allowing enough time in the session to complete homework in the session whilst adopting a collaborative approach at all times:

So we do it together in the session. I've not forced writing things down. Some patients just want someone to listen to them. There is a need to feel heard. A lot of patients were angry because they felt unheard and a lot of the patients felt done to in terms of people making them have medication.

Experiential work: promoting creativity

What emerged from the interviews was the importance of using being ‘creative when setting up behavioural experiments’ (Laura). One of the participants highlighted how a process of gradual, supported exposure had safely enabled one patient to face what was frightening him, and sponsored coping:

It was more behavioural. So some of the experiential stuff that we did was important . . . because he wouldn't come out of his room for sessions . . . So I used to have to see him in his room. So I would actually meet him at the door and he would be sat on his bed and slowly we moved him towards the door and me into the corridor on a chair and then slowly we moved him from there to going for walks down the corridor and coming back again (Maria).

In the following excerpt Ruth discussed how she frames behavioural experiments dealing with interpersonal and relational issues:

You have to ask them to canvass opinion from others and I think that works. So you can say to them, well you know next time you talk to your mum ask her what she thinks about this; or have you got a close friend you could ask them what they would think if you said X, Y and Z . . . They can't do it for everyone because they don't trust everyone. They don't want everyone to know their issues. So whereas you could go and do a survey in the middle of a town centre, you would get masses of responses wouldn't you? How many are you going to get here?

Dynamic focus creating an enabling space

Patient-focused treatment: ‘responsive and flexible to patients’ needs

The key phrase that recurred in the interviews was ‘being responsive’. Responsivity refers to ‘the delivery of treatment programs in a manner that is consistent with the abilities and learning style of the client’ (Wheeler and Covell, Reference Wheeler, Covell, Tafrate and Mitchell2014, p.310). Modifications and changes in the name of ‘responsivity’ were applied to treatment manuals (programmes):

There is no such thing as manuals I guess in this environment because really and truly you would adapt them all the time (Maria).

Longer term treatment

All the therapists gave a variety of reasons as to why longer treatment is necessary, including patients’ ‘risk of reoffending’, ‘complexity of difficulties’ presented, ‘readiness to change’ and ‘engagement difficulties’, amongst others:

The treatment should be individualized and slowed down. Slowed down so much, because people have such a low ability to concentrate. You have to whip through the bits that they don't find interesting to be able to hold their attention and hold their engagement which is not ideal. It's hard, and it takes longer (Ruth).

Jo emphasized that establishing a working agreement between the therapist and patient can take the same amount of time that a full treatment provided to a patient in the community:

Sometimes that therapeutic relationship takes a long time to build . . . maybe your 12 weeks that you would have finished your therapy in the community that actually it takes that long to get somebody in a room to start talking about whatever issue it is . . .

Using an eclectic approach

Most of the participants claimed that they were weaving additional elements into their CBT approach in order to treat the patients’ presenting problem:

Find the angle that works for each person. It's possible to weave it in to every little bit of work and it's great, it's helpful. It does things, when they get it they really get it and it's helpful and useful. They will use it all their lives but they are going to need other stuff too. I think CBT is helpful for people with a section of their life that needs a bit of help but when their whole life needs help, it's not a big enough sticking plaster. You need so much more healing than CBT on its own can offer.

An emphasis on ‘non-specifics’: a client-centred CBT delivery

Building the therapeutic relationship

The participants reported that building trust and rapport was essential for the therapy and that without this, the therapy could not be effective: ‘if you haven't got that relationship then the therapy is going nowhere’ (Laura). The role of trust, was pointed out by Ruth, to be highly connected to this process, and all the more vulnerable to rupture where lack of trust, or abuse of trust was present in the histories and present lives of the patients. Therapy in this case offers an opportunity to (re-)experience some safety in the presence of another person. However, as Chantelle highlighted, building and maintaining a trusting alliance typically requires an extra sensitivity in this setting: ‘You really got to earn it. You really got to prove yourself that you are trustworthy and it's really fragile’.

Using patient-centred language

Participants stressed the importance of using the patients’ language rather than using jargon; this can also help in building and maintaining the therapeutic relationship, and bridging any perceived or imagined gaps in thought or experience between the two participants

If you are thinking about encouraging people to do homework ‒ so thought records or mood diaries . . . So for anger for example, you might say anger whereas a patient might say well I don't get angry but I get irritated. So it's about finding the common wording that works, and sometimes it can take a while (Jo).

Promoting safety

Risk awareness and management

Most of the participants described risk management and assessment as vital to preserve safety. Maria reported that she is careful not to upset or distress patients who have complex needs in order to maintain the therapeutic relationship:

Risk management is key. I think for me it was always important to keep myself safe by ensuring that I didn't upset my patients and in terms of keeping the therapeutic alliance I felt it was important to not have my patients disengaged too soon . . . so really being on side with them.

Furthermore, Ruth added how she carefully manages patients who struggle to regulate their arousal levels:

I think the level of arousal that you meet with if you do set off a trigger with people here it is quite spectacular at times and your job is just to manage arousal as well as make sense of what's happening. You can come back to making sense of it another time but not in the moment.

Discussion

The common theme emerging from the data is consistent in highlighting the complexity of forensic patients’ needs and difficulties, and the influence of these on therapy delivery, a finding previously observed by McGauley (Reference McGauley, Bartlett and McGauley2010) and Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Simourd, Tafrate, Tafrate and Mitchell2014). All the participants identified competing needs presented by forensic patients that went beyond diagnoses; and led to changes in professional practice in an effort to be clinically responsive and maintain efficacy. The findings are consistent with previous literature that suggests that complex cases require an eclectic and integrative approach based on the patients’ needs and social context (Livesley, Reference Livesley2003, Reference Livesley2007).

How to start CBT in forensic settings?

A key aspect that participants emphasized was the extent and severity of the patients’ psychological disturbance, due to both their developmental experiences and severe mental illness. It is hypothesized that this impacts upon the patients’ ability to trust others, which adversely affects the building of the therapeutic relationship (Adshead and McGauley, Reference Adshead, McGauley, Bartlett and McGauley2010), such that therapy took time to commence safely in some circumstances. The participants also spoke about the patients’ emotional disturbances and their long-standing habits of emotional avoidance and suppression (Kroner and Reddon, Reference Kroner and Reddon1995). Some patients therefore struggle to see the rationale for CBT or believe that it could create a healthier way of processing and expressing emotions, and they seemed to lack motivation to change.

The complexity of the case material was also a barrier to starting CBT. Men often had serious mental illness and co-morbid personality disorder, in addition to concurrent diagnoses of past substance misuse, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). The functional link between their mental states and offending was often obscure, and formulations were inevitably complex. It was not always clear to therapists what therapeutic focus was most salient to their patients, given the complexity of their problems.

Another key aspect was the ethical challenge faced by participants in offering CBT. One of the major concerns was how to balance issues of confidentiality with risk management in a forensic setting where security takes precedence (McGauley, Reference McGauley, Bartlett and McGauley2010). Participants were bound to follow hospital-based policy in relation to the necessary sharing of information with the MDT, but also maintain a therapeutic alliance with the patient. Informing patients about the limits of confidentiality at the beginning of therapy, and explaining the ethical principles that underlie this position is recommended (BABCP, 2010; BPS, 2011).

Respecting patients’ autonomy is a key ethical principle in all health care, but is sometimes more complex to deliver in psychiatric settings, needing to be ‘rethought’ (Adshead, Reference Adshead, Bartlett and McGauley2010, p. 306). Although forensic patients can refuse to engage in therapies, it may be that lack of engagement influences decisions about their liberty. Engagement and motivation require a range of therapeutic skills by practitioners, including acknowledgement that motivation to change may not be a ‘free’ decision. Participants describe how active listening informed their working understandings, or case formulation, so that they could help patients make sense of their situation, and support them via alliance building to engage with staff on their journey of personal, clinical and ‘secure’ recovery (Moore and Drennan, Reference Moore and Drennan2013).

Adaptations in CBT delivery

Psychological treatment in this setting requires practitioners to respect the ‘responsivity principle’ (Andrews and Bonta, Reference Andrews and Bonta2003) which means responding in a timely manner to need, and adapting material to suit the offender-patient. A recent review of CBT for offenders (BABCP, 2013) also makes this point given the evidence that adaptation can enable the therapist to form and maintain an alliance with a person who may be frightened and suspicious about therapy and its value to them. This study was consistent with this, finding that therapists reported having to work hard at their therapeutic relationship and use strategies to establish a working alliance (Young, Reference Young1999; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Freeman and Davis2004; Beck, Reference Beck2005).

Between-session homework is a necessary element of CBT (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Lampropoulos and Deane2005), and is linked to improved clinical outcomes and development (Burns and Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Burns and Nolen-Hoeksema1991; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Deane and Ronan2000; Kazantzis and Lampropoulos, Reference Kazantzis and Lampropoulos2002; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Deane and Ronan2004). However, all the participants in this study described factors that impeded patients in doing homework: low motivation, symptom-related non-compliance (Kazantzis and Shinkfield, Reference Kazantzis and Shinkfield2007), the difficulty of the task, lack of perceived relevance to session content, mis-match in treatment goals (Fehm and Mrose, Reference Fehm and Mrose2008), confidentiality factors, and stigma that was linked to shame and/or reluctance/anger about diagnosis, detention and offending (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Steffan, Shaw and Wilson2007). Participants reported the importance of being flexible and described how they had adapted the setting of homework to work around the constrained tailoring material to make it more understandable and acceptable to patients who were particularly likely to monitor for coercion.

Participants described various challenges in setting behavioural experiments (BE), including the context, misunderstandings from ward staff and the patients’ lack of trust in trying out different skills. Some of these are common pitfalls that may be found in any setting (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004), but others may be related to the restricted atmosphere of the hospital and institutional anxieties about patients behaving differently. Participants described creative solutions, consistent with those described by Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004) using a range of methods, including imaginal, interactive, behavioural and experiential methods (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989; Beck, Reference Beck1997; Wells, Reference Wells1997; Safran and Muran Reference Safran and Muran2000) as ways of adapting interventions to the needs of the patients.

Another important way in which the HSH population was different related to time. CBT is usually delivered in comparatively short periods of treatment, where 20 weeks constitutes long-term treatment. In secure care, all phases of treatment (formulation, rationale engagement, goal setting, homework, etc.) take much longer. Forensic patients resemble patients with long-term chronic conditions, including personality disorders, who appear to benefit from treatment over a longer time period (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Banon and Ianni1999; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop and Heard2006; Clarkin et al., Reference Clarkin, Levy, Lenzenweger and Kernberg2007). Although long-term treatment can be offered in secure care, there are risks of inducing dependency and feelings of helplessness in patients (Annesley and Sheldon, Reference Annesley and Sheldon2012).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is its originality; there does not appear to be any previous study about the challenges of offering CBT in a high secure psychiatric service. Sources of bias include the researcher's previous relationship with the participants, many of whom were ex-colleagues; her own experience of work in a high secure service; and her clinical and theoretical perspective.

Unconscious bias in the analysis of the textual material was addressed as follows:

-

• Themes were validated with reference to direct quotations from the raw data;

-

• Findings were qualified and supported by the literature where possible;

-

• The researcher made reflexive issues explicit;

-

• Credibility checks between two researchers created a more accurate account of the themes.

These findings can only be considered as preliminary but would justify a future nomothetic (group-based) enquiry to generate population-related evidence. The other significant limitation of the study is that of gender role expectation and stereotypes: all participants were female professionals working in a male-only in-patient service, and issues of gender may have influenced the therapeutic relationships under examination. An extension would be to include men as representative of the gender mix in the hospital.

The final limitation to consider is the absence of reference to outcome criteria or the measurement of clinical change/effectiveness. The factors explored (that is how environmental context and clinical factors might impact on CBT clinicians) lent themselves well to a qualitative exploratory interview format. The uniqueness of complex needs populations, whose presentation is inevitably atypical, and highlights the value of qualitative enquiry for revealing differences of idiographic importance (Jones, Reference Jones2007, Reference Jones, Tennant and Howells2010, Reference Jones2012).

Conclusion and implications

The participants in this study demonstrated therapeutic skills and knowledge, and creative approaches in therapy to work around the constraints of the setting. With regard to treatment, CBT can be flexibly administered, which is an asset with this population, with its breadth of application and collaborative style of delivery. Therefore, the results of this study suggest that CBT is a valuable model in the options for intervention in forensic settings precisely because it can be applied flexibly and creatively in a way that meets criminogenic and therapeutic individual needs.

A final observation relates to the demands of mental health work on therapists working in secure settings. Such work has the potential to result in increased levels of compassion fatigue and burnout (Paris and Hoge, Reference Paris and Hoge2010)., To reduce the impact of these potential risks to staff for patients, it is important that practitioners access supervision and other reflective spaces that are provided to them (Adshead, Reference Adshead, Bartlett and McGauley2010; Daykin and Gordon, Reference Daykin, Gordon, Willmot and Gordon2011).

Other implications for good practice were elicited in interview analysis:

-

• The value of collaborative working using the CBT model as an explanatory framework for making sense of challenging behaviour for other members of the multidisciplinary team;

-

• How practitioners decide when it is possible to work with CBT, and when not;

-

• How to support clinicians and staff teams to keep a focus on change and possibility when the difficulties are enduring, and to promote engagement and inclusion by seeking the patient's perspective and guidance (Moore and Drennan, Reference Moore and Drennan2013).

In summary, this study offers an insight into the therapists’ experience of offering CBT to patients detained in a high secure psychiatric hospital. Its findings would potentially be of benefit as a resource for professionals at various stages of training who work with detained patients.

Main points

-

(1) As robust efficacy studies contribute toward evidence-based practice, CBT has emerged as a treatment of choice for emotional disorders, and is now formally recommended in national guidelines for offenders in prison and secure psychiatric services. However, the application of CBT for those with mental health needs and serious offending histories requires further exploration.

-

(2) There is clear evidence that treatment interventions with offender patients present a challenge related to the kaleidoscopic nature of complexity with which this population typically presents.

-

(3) The features that make the therapeutic work in HSHs challenging include the risks relating to history of extreme behaviour, to mental state, and the constraints inherent in the ‘treating’ environment which both curtails behavioural opportunity and contains it. Patients often alternate between presenting as threatening aggressors and vulnerable adults, with histories of victimization that have been profoundly shaping of their identity and interpersonal coping style and attitudes.

-

(4) The study highlights the importance of creating an enabling safe space, by being ‘responsive’ to the patients’ needs and also emphasizes the importance of working to establish a baseline for ‘safety’ in all alliances wherever possible.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study received approval from the University Ethics panel, Buckinghamshire New University and was also approved by the West London Mental Health Trust Clinical Effectiveness and Audit Committee.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants who participated in the research. In addition, the contributions of Dawn Lankester who partly supervised this piece of work as part of an MSc is greatly acknowledged. Thanks also goes to colleagues from Broadmoor Hospital's Centralised Groupwork Service for their assistance and encouragement, in particular Dr Claire Wilson and Dr James Tapp. We would also like to thank Dr Gwen Adshead and Tony Attard for helpful comments and feedback on early drafts of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Learning objectives

-

(1) To identify ‘challenging’ aspects of therapy with patients who are in secure care.

-

(2) To investigate how complexity and competing needs affect therapeutic practice in secure care.

-

(3) To emphasize the importance of ‘safety’ and ‘responsivity’ in the therapeutic alliance in secure care.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.