Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious, difficult-to-treat psychiatric disorder that causes significant emotional distress and economic burden, both socially and to healthcare systems.Reference Gunderson1–Reference Hastrup, Jennum, Ibsen, Kjellberg and Simonsen4 A variety of psychotherapies, such as dialectical behaviour therapy, mentalisation-based treatment and systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving, have shown benefit in reducing many of the core symptoms of BPD.Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop and Heard5–Reference Storebø, Stoffers-Winterling, Völlm, Kongerslev, Mattivi and Jørgensen7 Healthcare systems, however, often lack the funding and appropriate expertise to implement these treatments, and finding trained therapists has been difficult for many people with BPD.Reference Adam, Leila and Fruzzetti8,Reference Choi-Kain, Albert and Gunderson9 Although research on the use of medication is ongoing, no drug has yet been approved for the treatment of BPD. Antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline), anticonvulsants (e.g. lamotrigine, topiramate) and antipsychotics (e.g. quetiapine, olanzapine) have all been examined,Reference Lieb, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Stoffers10–Reference Flewett, Bradley and Redvers13 but current medication options for BPD often provide only partial relief and may have pronounced side-effects. Although medications are not currently approved for BPD, many patients often receive some medications in clinical practice, such as those medications previously studied for BPD,Reference Lieb, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Stoffers10–Reference Flewett, Bradley and Redvers13 for symptomatic relief of symptoms of depression, anxiety or impulsivity.

BPD is characterised by a pervasive pattern of affective instability, difficulty with impulse control and aggressive outbursts. Although poorly understood, dysfunctions in the serotoninergic and dopaminergic systems have been implicated in, and considered as possible contributing factors for, these core symptoms of BPD.Reference Perez-Rodriguez, Bulbena-Cabré, Bassir Nia, Zipursky, Goodman and New14–Reference Oquendo and Mann17 Brexpiprazole is a novel serotonin-dopamine activity modulator with partial agonist activity at the 5-HT1A and D2/D3 receptors, combined with potent antagonist effects on the 5-HT2A, a1B- and a2C-adrenergic receptors.Reference Maeda, Sugino, Akazawa, Amada, Shimada and Futamura18–Reference Yoon, Jeon, Ko, Patkar, Masand and Pae20 A recent meta-analysis of double-blind placebo-controlled studies concluded that brexpiprazole resulted in significant improvement in both schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, and was well tolerated.Reference Antoun Reyad, Girgis and Mishriky21 In addition, because of low rates of side-effects reported in clinical trials for other disorders to date, one would expect brexpiprazole to be fairly well-tolerated in people with BPD. Thus, brexpiprazole may have distinctive properties that make it a promising option to explore in a rigorous clinical trial for people with BPD.

Aims

The aim of the present study was to examine the efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole compared with placebo in adults with BPD. We hypothesised that brexpiprazole would reduce the core symptoms of BPD to a greater extent than placebo, and would be well tolerated.

Method

Eighty individuals aged 18–65 years (mean age 39.7 ± 11.6; n = 45 women [56.3%]) with a current established diagnosis of BPD (see below for assessment procedures) were recruited from clinic and local advertisements for a 13-week, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study in which brexpiprazole or placebo was administered in a 1:1 fashion. All 80 participants had current BPD per DSM-5 criteria.

Inclusion criteria for the study were the following: aged 18–65 years, primary diagnosis of BPD, a total score of at least 9 on the clinician-rated Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at study entry, and the ability to understand and sign the consent form. The exclusion criteria were as follows: unstable medical illness; schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; an active substance use disorder; current pregnancy or lactation, or inadequate contraception in women of childbearing potential; a suicide attempt within the 6 months before the baseline visit or significant risk of suicide (in the opinion of the investigator, defined as a ‘yes’ to suicidal ideation questions 4 or 5, or answering ‘yes’ to suicidal behaviour on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale within the past 6 months); illicit substance use based on urine toxicology screening (excluding marijuana); initiation of psychological interventions within 3 months of screening; use of any new psychotropic medication started within the past 3 months before study initiation; previous treatment with brexpiprazole; and cognitive impairment that might interfere with the capacity to understand and self-administer medication or provide written informed consent.

Participants were recruited to the study from 1 June 2018 until 16 December 2020.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. This study is registered with Clinicaltrials.gov, under identifier NCT03418675. After a comprehensive explanation of study procedures and an opportunity to ask any questions, all participants provided written informed consent. Participants were compensated $200 for time and travel associated with the ten study visits.

Study design

Eligible participants were assigned to 13 weeks of double-blind brexpiprazole or placebo treatment (12 weeks of treatment, with a 13th week tapering/safety phase). The University of Chicago's investigational pharmacy, which was independent of the research team, randomised all participants (block sizes of eight, using computer-generated randomisation with no clinical information) to either the brexpiprazole or matching placebo in a 1:1 fashion. The study blind was maintained by having placebo and active treatments of identical size, weight, shape and colour, as confirmed by the independent pharmacy.

All participants were assessed each week for the first 2 weeks, and then every 2 weeks after that. At week 12, participants were started on a 1-week taper off of the medication/placebo. The initial dose of brexpiprazole was 1 mg/day and was increased to 2 mg/day by week 2, and then remained at 2 mg/day for the remaining 10 weeks of the study. Dosage changes and reductions were not permitted, and participants were discontinued if they experienced intolerable side-effects. The dose range was based on safety and efficacy data from previous studies using brexpiprazole. We selected the maximum dose of 2 mg/day, which is lower than the US Food and Drug Administration-approved maximum dose of 3 mg/day for major depressive disorder, because of increased potential for side-effects at the 3 mg/day dose.

All efficacy and safety assessments were performed at each visit. Participants who did not adhere to their study medication regimen (defined a priori as failing to take placebo or active medication for three or more consecutive days) were discontinued from the study. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, study participants (participants 62–80) were allowed to perform their baseline and follow-up visits online via encrypted videoconferencing with the clinician, instead of in-person visits. Blood samples, however, were at the discretion of the study investigator, and where considered medically necessary, the participant had them drawn locally and submitted to the study team.

Assessments

Those individuals who appeared appropriate for the study, based on telephone screening, were invited for a baseline assessment. The duration of the baseline assessment was approximately 90 min and included the following: informed consent, demographic data, concomitant medications, family history data, medical evaluation, urine pregnancy test, urine drug screen and a psychiatric evaluation (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview).Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller22

Efficacy evaluation

The a priori (i.e. determined in the protocol document before study commencement) primary outcome measure was the change from baseline to week 12, determined using the total score on the ZAN-BPDReference Zanarini, Vujanovic, Parachini, Boulanger, Frankenburg and Hennen23 (the data from week-13 taper phase was not considered for the efficacy analysis, but was used for safety assessments). This semi-structured interview has anchored ratings (0 = no symptoms, 4 = severe symptoms) on nine items that correspond to the DSM-5 BPD criteria and assesses these symptoms over the past week. Previous pharmacotherapy studies support the assertion that the ZAN-BPD scale is sensitive and appropriate to detect even small changes in BPD symptoms over time.Reference Zanarini, Schulz, Detke, Tanaka, Zhao and Lin12,Reference Black, Zanarini, Romine, Shaw, Allen and Schulz24

Secondary efficacy measures included the patient-rated version of the Sheehan Disability Scale,Reference Sheehan25 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for DepressionReference Hamilton26 and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety.Reference Hamilton27

Study withdrawal and safety

If a participant withdrew from the study, all instruments administered at the baseline visit were completed at the final visit. Safety and tolerability were assessed with spontaneously reported adverse events data, the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale and by evaluating premature termination. Safety assessments (sitting blood pressure, heart rate, adverse effects, suicidality and concomitant medications) were documented at each visit for those who enrolled before COVID-19 restrictions. Participants who were ever an imminent suicide risk were removed from the study and appropriate clinical intervention (e.g. hospital admission) was arranged. Assessment of side-effects was done at each visit.

Data analysis

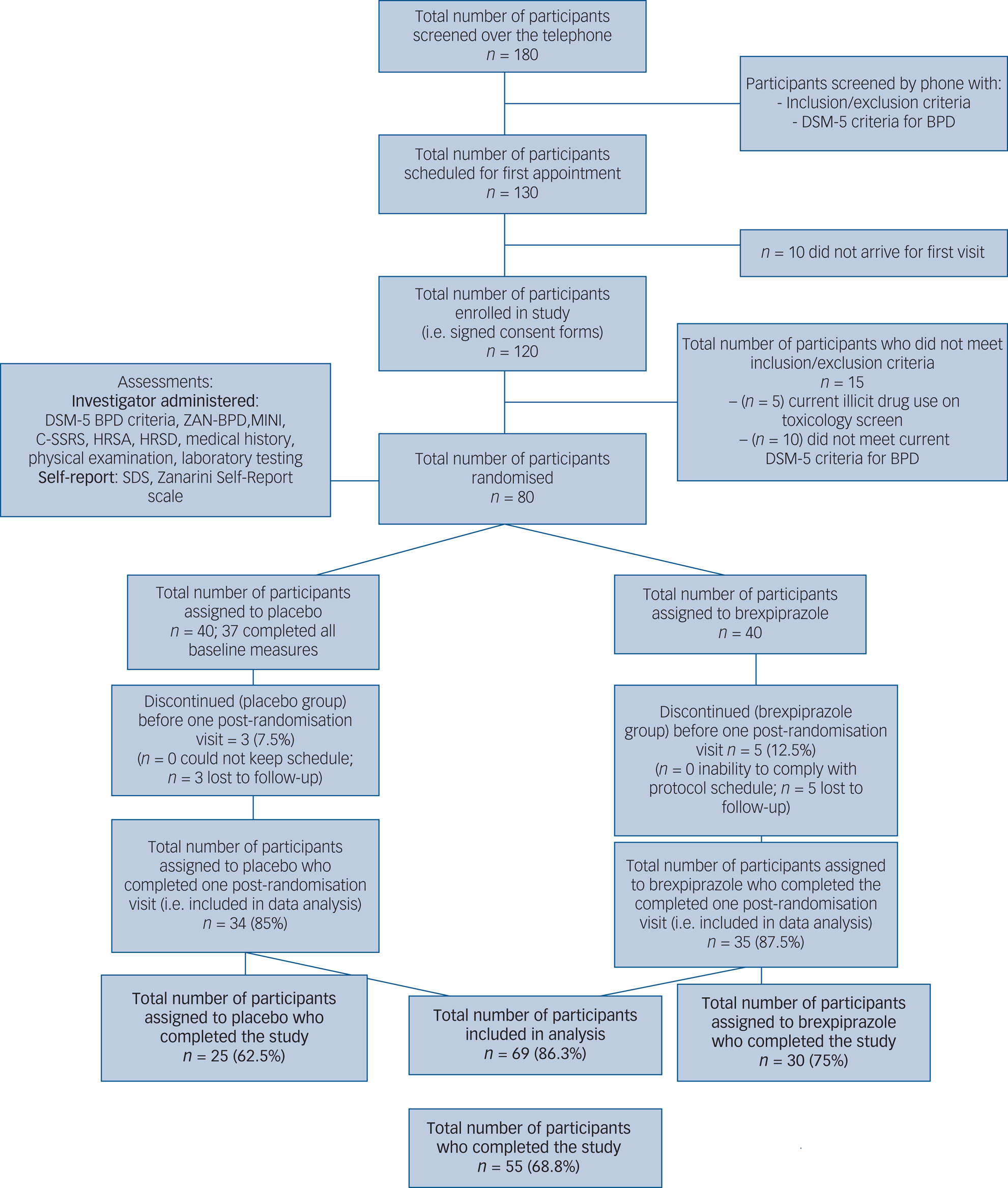

Efficacy analysis involved all visits during the 12-week double-blind treatment phase (up until week 12). All enrolled participants were included in the analyses of baseline demographics and safety according to an intention-to-treat principle. For statistical analysis, the full-analysis set was defined as all participants who took the study drug for at least 1 week and had at least one post-baseline primary efficacy assessment (eight participants dropped out before the first post-baseline assessment; see Fig. 1). The safety-analysis set was defined as all randomised participants who took at least one dose of the study drug and completed at least one follow-up safety assessment.

Fig. 1 CONSORT diagram. Participant flow diagram for brexpiprazole versus placebo in the treatment of BPD. BPD, borderline personality disorder; C-SSRI, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; ZAN-BPD, Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder.

To assess efficacy, we used a linear mixed-effects regression model, with the ZAN-BPD total score as the dependent variable. Independent variables included terms for treatment group, study visit and treatment×visit interaction. Imputation was not undertaken for missing data. Correlation between visits for the same participant was modelled with an unstructured correlation or autoregressive correlation, depending on best fit. Residuals and model fit were examined. The prespecified effect of interest was the treatment×visit interaction, specifically the baseline to visit 8 change (i.e. week 12) between groups. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) was used for analysis. All testing was two-sided and P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The planned study sample size was calculated for the primary end point of change from baseline. The power calculation was performed to detect a minimal clinically relevant difference of 3.0 (s.d. 3.5) in the total score on the ZAN-BPD between medication and placebo, based on other studies that have use the same primary outcome measure.Reference Zanarini, Vujanovic, Parachini, Boulanger, Frankenburg and Hennen23 It was determined that 35 participants were needed in each treatment group to detect a difference with an overall 5% type 1 error risk. Given the particularly low rates of adverse events reported with brexpiprazole, we expected a low drop-out rate, and therefore a smaller sample was needed.Reference Brown, Khaleghi, Van Enkevort, Ivleva, Nakamura and Holmes28

Results

A total of 80 participants provided informed consent, were enrolled and randomised to brexpiprazole or placebo. Participant flow through the study is presented in Figure 1 (CONSORT diagram). Of the 80 participants, 40 were assigned to placebo, but only 37 completed all baseline measures. Of the 40 assigned to brexpiprazole, all 40 completed the ZAN-BPD scale, but only 37 completed the rest of the baseline measures.

Demographic characteristics of participants in both groups at baseline are presented in Table 1. Baseline BPD scores were reflective of moderate severity (15.0 ± 4.5 for the placebo group and 14.9 ± 4.4 for the brexpiprazole group; Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used to assess for differences between groups at baseline; P = 0.9878). Of the 80 randomised participants, 69 (86.3%) returned for at least one post-baseline visit.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants with borderline personality disorder at study entry

ZAN-BPD, Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder.

Of those assigned to brexpiprazole, 12 (out of 40; 30%) were receiving at least one concomitant psychiatric medication (eight were on antidepressants, five were on antiepileptics and three were on stimulants), whereas of those assigned to the placebo, 14 (out of 40; 35%) were receiving at least one concomitant psychotropic medication (ten were on antidepressants, seven were on antiepileptics and three were on stimulants).

Of the adults assigned to brexpiprazole, 25 (62.5%) had at least one current comorbid psychiatric disorder (19 had an anxiety disorder, 15 had a mood disorder, four had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and four had an eating disorder). Among the people assigned to the placebo, 26 (65.0%) had at least one current comorbid psychiatric disorder (19 had an anxiety disorder, 13 had a mood disorder, one had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and three had an eating disorder).

A total of 30 out of 40 participants (75%) assigned to treatment with brexpiprazole and 25 out of 40 participants (62.5%) assigned to treatment with placebo completed the 12-week trial (Fig. 1). Of the 25 participants who failed to complete the study, participants generally withdrew because of perceived lack of efficacy or inability to adhere to the study schedule.

The primary outcome variable was ZAN-BPD total scores. Figure 2 shows means at each visit by group. The treatment group went from a mean score of 14.9 (s.d. 4.4) at study entry to 3.1 (s.d. 3.9) at end of the 12 weeks, compared with a change of 14.9 (s.d. 4.5) to 8.4 (s.d. 5.5) for the placebo group at the end of the 12 weeks.

Fig. 2 Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) total score by visit by group.

Regression model for ZAN-BPD total score

There were 69 participants included in this analysis (with baseline and at least one follow-up visit with ZAN-BPD total scores). The model with visits 1–8 included 494 total data points. The statistical model indicated a significant effect of group (F = 4.00, P = 0.0497) and visit number (F = 39.74, P < 0.0001), as well as significant main effects of visit number and treatment group interaction (F = 3.13, P = 0.0031).

In the model, the treatment×time interaction term is statistically significant, and is driven by the jump in scores at visit 8 in the placebo group. Figure 3 shows that at the various visits, the treatment group and placebo group have similar scores with similar 95% confidence intervals, except for visit 8 in the placebo group. This non-overlapping confidence interval with the visit 8 treatment group confidence interval is driving the significance of this term in the model.

Fig. 3 Least-squared means for visit × treatment group. Graph shows, for each time point, least squares means for the primary outcome measure in the brexpiprazole group (‘1’) and placebo group (‘0’), respectively. It can be seen that the 95% confidence intervals overlapped at each time point for the groups, except for the final treatment visit (visit 8), where it can be seen that the placebo group had higher ZAN-BPD total scores than the treatment group. ZAN-BPD, Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder.

In terms of the secondary measures, there were no significant differences during treatment, in terms of anxiety or depression scores.

Adverse event data from the trial showed that brexpiprazole was generally well-tolerated, with minimal side-effects that were of mild intensity. Of the 37 participants assigned to the placebo, 19 (51.4%) reported at least one side-effect, with the most common being nausea (six participants), fatigue (four participants), restlessness (three participants), headaches (two participants), hallucinations (two participants), sleep problems (two participants), tremor (one participant), sweating (one participant) and increased appetite (one participant). Of the 40 participants assigned to brexpiprazole, 11 (27.5%) reported at least one side-effect, with the most common being restlessness (three participants), dry mouth (three participants), nausea (two participants), fatigue (two participants), headache (one participant) and increased appetite (one participant). The groups differed in the number of people experiencing adverse events, because of significantly lower likelihood of adverse events occurring with active treatment compared with placebo (χ2 = 4.5979, P = 0.0320).

Discussion

This study showed that brexpiprazole may have had some effect on BPD symptoms; in fact, the primary end point was met and there was a significant result. The overall clinical meaningfulness of these results, however, is open for interpretation, given that the significance of these results were primarily because of differentiation from placebo, specifically at 12 weeks. Thus these data make it difficult to imagine that a drug mechanism gave rise to the differences in ZAN-BPD scores at the final visit. These findings need to be interpreted with some caution. Although the primary outcome measure separated from placebo at the final visit, it had not done so for the first 10 weeks of treatment. This may be due because of a robust placebo response in BPD, as evidenced from previous pharmacological trials.Reference Zanarini, Schulz, Detke, Tanaka, Zhao and Lin12,Reference Black, Zanarini, Romine, Shaw, Allen and Schulz24,Reference Van den Eynde, Senturk, Naudts, Vogels, Bernagie and Thas29 This late separation from placebo suggests that perhaps only longer trials can provide clear evidence of a strong drug effect, although it is unclear pharmacologically why benefits would not have accrued gradually over time rather than being evident mainly at a single time point. Another possibility is that because the trial was nearing its end, medication had some effect on rejection sensitivity versus placebo; thus, ZAN-BPD scores tended to increase in the placebo group, but less so in the active treatment group. Also, given that participants were informed at visit 8 that their medication would be tapered for the final week, it remains unclear as to whether some may have exaggerated treatment response (although why in one arm and not the other remains unclear). Longer studies may better delineate these findings and confirm a pharmacological response.

The placebo response in this study was quick and fairly sustained for several weeks. This type of robust placebo response is consistent with previous pharmacological studies in BPD.Reference Van den Eynde, Senturk, Naudts, Vogels, Bernagie and Thas29 This type of placebo response can lower statistical power and interfere with interpretation of results. Did the fortnightly visits provide some sort of nonspecific psychological support to those assigned to the placebo? One potential solution is to conduct longer trials with less frequent visits. It is unclear whether participants would participate in these types of trials. A placebo lead-in may also be needed to reduce some of this noise and allow for better examination of drug effect.

There are several limitations associated with this study. First, there were some missing data, largely because of switching to an online platform given restrictions from COVID-19. Second, the relatively small sample size as a result of drop out in the early weeks of the study may further call into question whether some of the secondary measures may have been significant if adequately powered. Also, our percentage of participants who identified as non-female (i.e. as male or neither male nor female) was slightly larger (37%) than those in other studies (approximately 25%),Reference Zanarini, Schulz, Detke, Tanaka, Zhao and Lin12,Reference Black, Zanarini, Romine, Shaw, Allen and Schulz24 and whether certain medications affect people with BPD differently based on gender remains unknown. Finally, although well-tolerated, the activating side-effect of brexpiprazole may have jeopardised the blind potentially, although this seems unlikely given that participants were more likely to report side-effects with placebo.

Despite the limitations, brexpiprazole appears to have had some possible effect on BPD symptoms, but further studies are needed because of the significant effects evident specifically at the final time point. Given the strong placebo response, future studies should be well-powered and of sufficient duration to better determine what is a placebo response as opposed to a true drug effect.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.E.G., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues.

Author contributions

All authors took part in formulating the research question, designing the study, carrying it out, analysing the data and writing the article.

Funding

This study was funded by an investigator initiated grant from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. S.R.C.'s role in this study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship (110049/Z/15/Z and 110049/Z/15/A).

Declaration of interest

J.E.G. has received research grants from the TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors, Otsuka, Biohaven and Avanir Pharmaceuticals. He receives yearly compensation for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies, and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Norton Press and McGraw Hill. S.R.C. receives honoraria from Elsevier for editorial work, and previously consulted for Promentis. The other authors report no relevant disclosures.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.