Introduction

Spain is a country divided into regions that enjoy a high degree of political autonomy. These regions often have distinct historical origins and languages, which can lead to a strong sense of nationalism. This is particularly true in Catalonia, which has long sought a greater level of self-governance and, in recent years, has even called for independence from Spain. The issue has become a major political topic, with independence parties gaining power in regional elections and pushing for a referendum on independence in 2017. Despite the regional government’s lack of legal authority to hold the referendum, it took place on October 1st of that year.

The response to the independence referendum and subsequent declaration of independence by separatist parties was varied, but one of the most notable and powerful reactions was the use of the Spanish flag by those who opposed the independence process. This display of national pride and unity was a powerful symbol of their rejection of the separatist movement.

As the political crisis in Catalonia unfolded, flags became a prominent symbol of the conflict. Both sides used flags to express their stance on the issue, with supporters of independence flying the Catalan flag (known as the “Estelada”) and opponents flying the Spanish flag. The sight of streets filled with flags, as well as the use of flags on balconies, led some to refer to the situation as a “flags war” or the “Spain of the balconies.” While the use of the Estelada was a way for the independence movement to show its determination, the use of the Spanish flag by those across the ideological spectrum was a powerful expression of their opposition to independence.

For example, the Spanish national soccer team’s victory in the 2010 World Cup sparked a widespread display of the national flag like never before. It’s worth noting that the Spanish flag had traditionally been associated with the conservative political spectrum. However, the triumph of the team allowed people to express their national identity without fear of being perceived as supporters of ultraconservative ideologies. It’s important to recognize that identification with the team doesn’t imply a monolithic understanding of Spain; rather, it can represent shared identities and can even coexist with other identities that differ from a Spanish one (Sánz Hoya Reference Sánz Hoya, Saz and Archilés2012).

In the Catalonian conflict, many people who would never have chosen the Spanish flag as an image of their political positioning have hoisted it as a symbol of national unity. It has become part of the urban landscape, and it is an object not usually repaired consciously but unconsciously perceived. It makes sense, then, to ask what effect the extraordinary ubiquity of the Spanish flag in citizens’ everyday lives might have on their opinions. In our study we try to find out whether these effects exist and if so, how they influence the political opinion of these citizens.

To achieve our objective, we conducted a study to investigate the effect of a subliminal stimulus, specifically an image of the Spanish flag, on political attitudes toward the Catalan independence movement. We sought to determine whether the image of the Spanish flag contributes to segregation or conciliation and whether it has a positive or negative effect on public mood and perception of the independence process.

We conducted two experiments to compare the effects of these two types of subliminal stimuli: flags and emoticons. The experiments were designed to assess the influence of these stimuli on political opinions. Participants were exposed to either a flag or emoticon subliminal stimulus and their responses were compared with those of a control group that was not exposed to any stimuli.

The results of our experiments provide compelling evidence that subliminal stimuli, both flags and emoticons, can have a significant effect on political opinions. Specifically, we found that the effect of the emoticon stimulus was more pronounced than the effect of the flag stimulus.

First, we review the existing studies on the relationship between emotions and political opinions and behaviors, paying special attention to the effects produced by political objects, even those perceived in a nonconscious way. Then, we describe the experiments and discuss their results, to end with a section of conclusions in which we evaluate the set of responses obtained.

Emotions, behavior, and opinions

Emotions influence our behavior, they influence the decisions we make (Cunningham Reference Cunningham1988; Patel and Schlundt Reference Patel and Schlundt2001; Teven Reference Teven2008; Tumasjan et al. Reference Tumasjan, Sprenger, Sandner and Welpe2010; DeWall et al. Reference DeWall, Baumeister, Chester and Bushman2016; Alashoor, Al-Maidani, and Al-Jabri Reference Alashoor, Al-Maidani and Al-Jabri2018). Although emotion is variable and depends on circumstances (Eldar et al. Reference Eldar, Rutledge, Dolan and Niv2016), this neurophysiological reaction to a specific event, which is an automatic process, may depend on our learning (Damásio Reference Damásio1994, Reference Damásio1999; Carter and Smith Pasqualini Reference Carter and Pasqualini2004) or the rewards we hope to obtain (Eldar et al. Reference Eldar, Rutledge, Dolan and Niv2016). We can understand emotions as a catalog of responses that control our actions. For each life event, the somatic consequences are marked and reproduced when that event appears again. Emotions are a series of learned patterns that we use in all kinds of events (Damasio Reference Damásio1994, Reference Damásio1999; Bechara and Damasio Reference Bechara and Damasio2005).

The capacity of emotions to condition our opinions depends on two factors: the storage of these markers and these markers and their correct activation. It is the long-term memory that stores this information in our brain in the form of nodes and builds an associative network of meanings and attributes about different political objects that shapes our beliefs and guides us before all kinds of situations (Vonnahme Reference Vonnahme2019).

Although many of the records we store in these nodes may have a rational root, affective stimulation shows a high efficacy in activating these networks (Bargh et al. Reference Bargh, Chen and Burrows1996; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000; Redlawks Reference Redlawsk and Redlawsk2006; DeWall et al. Reference DeWall, Baumeister, Chester and Bushman2016). According to authors such as Marcus et al. (Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000), emotional evaluation and reaction to symbols, people, groups, and events is generated before consciousness, especially in the face of emotions such as enthusiasm or anxiety (Mackuen et al., Reference Mackuen, Marcus, Neuman, Keele, Mackuen, Marcus and Neuman2007), which are capable of activating the disposition system. This disposition system guides our behavior and produces learned responses in order to save processing costs in the face of recurrent or known events (Carter and Smith Pasqualini Reference Carter and Pasqualini2004; Jameson, Hinson, and Whitney Reference Jameson, Hinson and Whitney2004; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000; Mackuen et al. Reference Mackuen, Marcus, Neuman, Keele, Mackuen, Marcus and Neuman2007).

Our emotions do not depend exclusively on us. Our social character and the dependence on the community in which we live decisively influence them (Ellisa and Faricy Reference Ellisa and Faricy2011). They are the result of a fragmented and continuous construction affected by a multitude of environmental factors, in many cases, beyond our control (as the collective euphoria for sporting success or the sadness that a rainy day can arouse). We can identify these environmental factors, both positive and negative, as public mood. This public mood is a diffuse affective state that citizens experience due to their belonging to a particular political community (Rahn, Kroeger, and Kite Reference Rahn, Kroeger and Kite1996). It is a climate of opinion through which citizens perceive and observe political issues and decide their preferences (Stimson Reference Stimson and Stimson1999). According to Ringmar (Reference Ringmar2017), the public mood is a product of a fragmented construction process in which our emotions toward a specific political object are contingent on the context in which we encounter it. The mood provides information (Rahn, Kroeger, and Kite Reference Rahn, Kroeger and Kite1996). It offers citizens a guide to know how they should behave, not as a conscious and rational element but rather as an unconscious and emotional one. The public mood acts like the soundtrack of a movie. Music helps the viewer interpret, through the emotions it evokes, the scenes that unfold (Ringmar Reference Ringmar2017).

Despite its differentiation from private mood, individuals possess the ability to attune themselves to the collective affective state and adjust their public response in accordance with anticipated expectations, as posited by Rahn, Kroeger, and Kite (Reference Rahn, Kroeger and Kite1996) and Weber-Guskar (Reference Weber-Guskar2017). Therefore, we can think that if we are able to reproduce the same or similar stimuli, even artificially, we will obtain the same responses. This cause and effect relationship, predictably, will also occur with political objects and behavior and political opinions.

The role emotions play in the choice of political judgments and opinions has been increasingly studied (Sinaceur, Heath, and Cole Reference Sinaceur, Heath and Cole2005; Teven Reference Teven2008; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Pillai, Lowe, Jung and Herst2009; O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, Balasubramanyan, Routledge and Smith2010; Tumasjan et al. Reference Tumasjan, Sprenger, Sandner and Welpe2010; Miller Reference Miller2011). For example, some research demonstrates the electoral effect of attributing negative events to a candidate (Lau Reference Lau1982); the effects on the approval of a proposal if it is presented with positive or negative language (Holleman et al. Reference Holleman, Kamoen, Krouwel, van de Pol and de Vreese2016); or the decrease in the legitimacy of governments and institutions as a result of negative campaigns (Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007).

The presence of some contextual stimuli related to political life causes a position taking that, far from being rationally founded, must be explained as the result of unconscious emotional reactions, even if they are reasoned and grounded as if they were the result of a process of conscious rational analysis (Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk1997; Baum and Jamison Reference Baum and Jamison2006; Redlawsk Reference Redlawsk and Redlawsk2006; Haidt Reference Haidt2013; Erisen, Lodge, and Taber Reference Erisen, Lodge and Taber2014). Among the stimuli that can give rise to relevant emotional reactions, the visual ones stand out. The presence or the exhibition to the subject of some images gives rise to emotional responses outside the conscience even if the stimuli are clearly visible (Rutchick Reference Rutchick2010). These objects activate, as we have previously explained, our political predispositions. Those that we retain in the form of an associative network in our long-term memory (Vonnahme Reference Vonnahme2019), a spontaneous and uncontrolled response (Bargh et al. Reference Bargh, Chen and Burrows1996; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000; Redlawks Reference Redlawsk and Redlawsk2006). The perception of the object or symbol will elicit an emotional response whenever that object signifies something. In this case, the citizens “will syntonize” their behavior to adapt it to what is expected (Lau Reference Lau1982; Ringmar Reference Ringmar2017).

This may be the case for national flags. Flags are political objects of (sometimes unconscious) perception that produce visible effects on our political behavior (Ferguson and Hassin Reference Ferguson and Hassin2007 Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007; Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008; Sibley, Hoverd, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Hoverd and Duckitt2011). Political science and social psychology have studied the use of nonconscious stimuli and their effects on opinions. Some of these researching activities are focused on the use of the flag, which has been defined as the political symbol par excellence (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1992; Guéguen, Martin, and Stefan Reference Guéguen, Martin and Stefan2017). As a general rule, flags are well known by citizens and have a conspicuous presence in the normal life of the institutions. The flag also represents the political ideals and values that are associated with the country (Conover, Searing, and Crewe Reference Conover, Searing and Crewe2004; Huddy and Khatib Reference Huddy and Khatib2007) and encapsulates the meaning of becoming part of a nation (Smith Reference Smith1998). For example, when these values and national security are threatened, the attachment to the flag usually increases (Skitka Reference Skitka2005; Guéguen, Martin, and Stefan Reference Guéguen, Martin and Stefan2017).

Flags, as symbols of the nation, are used in other types of exhibits, notably those of international nature. For these reasons, these symbols have become the most widespread, simple, and easily understandable symbol of the idea of the nation they represent, with an important emotional burden (Billig Reference Billig1995; Gellner Reference Gellner2005; Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008). It is practically impossible to find a citizen who does not know what the flag of his country is, even if he does not have certain knowledge about its origin or the meaning of its colors or figures.

The flag appears as a social construction full of meaning, which helps to substantiate the idea of the nation-state that surpasses the idea of homeland (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger1992). It summarizes the history of the nation and serves as a reminder of the individual’s belonging to the group. It represents ideas and feelings that the members of the nation should have. The flag represents the way in which a nation sees itself (Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008). Therefore, as a national symbol, flags promote national identification in several ways: (a) the individual is identified as part of a group; (b) it is a tangible representation of the group; (c) if (a) and (b) are met, group members should try to distinguish themselves positively from outside groups; and (d) it represents the group as a whole (Schatz and Lavine Reference Schatz and Lavine2007).

This could allow us to assume that exposure to the flag can make individuals think and behave in a way consistent with the worldview and the values associated with it (Hong et al. Reference Hong, Morris, Chiu and Benet-Martínez2000; Dumitrescu and Popa Reference Dumitrescu and Popa2016).

In accordance with the social identity theory, individuals define their identity, in part, based on their membership in social groups. These groups can be based on a variety of factors such as race, gender, nationality, or religion. According to this theory, people tend to identify more strongly with groups that they perceive as similar to themselves and that provide a positive social identity. Therefore, individuals strive to maintain a positive sense of self through their group memberships. Social identities can hold significant emotional weight and influence how individuals process information about themselves and others within their group, how they respond to changes in the group’s circumstances, such as triumphs or setbacks, and how they behave (Rahn, Kroeger, and Kite Reference Rahn, Kroeger and Kite1996; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Jost and Sidanius2004; Tajfel Reference Tajfel2010). The national flag, as an identity symbol, has the ability to influence individuals to alter their perspective and adopt the viewpoint of their national identity, if one exists. (Billig Reference Billig1995). They assume, thus, the stereotypes of the national identity and try to act according to them—that is, according to what they believe is proper to their nation (Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008). Some experiments have shown that those who are exposed to the flag tend to help and to cooperate with others if they are of the same group (Guéguen, Martin, and Stefan Reference Guéguen, Martin and Stefan2017). Moreover, those who are exposed to the flag buy preferably products marked with it (Wang and Zuo Reference Wang and Zuo2016; Guéguen, Martin, and Stefan Reference Guéguen, Martin and Stefan2017).

We can classify most of the research on the effects of the flag into two groups: those that detect an increase in nationalism and those that detect an increase in patriotism. In the first of it, the flag would increase the nationalist feeling of belonging to the group and of differentiation with the others, the foreigners (Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008). This response could increase exacerbation of aggressiveness and the rejection of those who are different or alien to the group, as shown in Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Enders-Comberg, Wagner, Christ and Butz2012) with German Flag. In some cases, this may be because the flag is often linked to the conflict, even to war (Ferguson and Hassin Reference Ferguson and Hassin2007) and it is used as a form of defense against aggression.

On the contrary, patriotism can be seen as a form of acceptance of others. Exposure to the flag can also increase patriotism and can increase egalitarian sentiments, as shown by Sibley, Hoverd, and Duckitt (Reference Sibley, Hoverd and Duckitt2011) with the New Zealand flag or Butz, Plant, and Doerr (Reference Butz, Plant and Doerr2007) with the United States flag, and it could lead to more moderate political positions, as Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007) showed in the case of Israel.

The distinction between nationalism and patriotism is a psychological categorization based on the critical or uncritical capacity of citizens with respect to the nation and their attitude toward the exogroup or minorities (Kosterman and Feshbash Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Druckman Reference Druckman1994; Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004). However, this dualistic view has been criticized for the difficulty of adequately delimiting these concepts (Viroli Reference Viroli1997; Spencer and Wollman Reference Spencer and Wollman1998; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2010, Reference Maxwell2018; Bitschnau and Mußotter Reference Bitschnau and Mußotter2022; Guibernau, Reference Guibernau1996). Despite this, several investigations coincide in pointing out that nationalism has an exclusionary attitude toward the exogroup or minorities (Kosterman and Feshbach Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Druckman Reference Druckman1994; Spencer and Wollman Reference Spencer and Wollman1998; Mummendey et al. Reference Mummendey, Klink and Brown2001; Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003; Heyder and Schmidt Reference Heyder, Schmidt and Schain2003; Weiss Reference Weiss2003).

Our study on the effects of exposure to the national flag does not focus on the dichotomy between nationalism and patriotism. Instead, we seek to investigate whether exposure to the flag may cause exclusionary effects, leading to divisions and conflicts between groups in society. Although Catalonia is part of Spain, Catalan independence supporters may be perceived as an exogroup (Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003) due to their subjective self-identification as not belonging to the nation. As in Skitka’s (Reference Skitka2005) research, overexposure to national flags in crisis situations, such as the Spain of balconies, may increase levels of nationalism. In other words, it can influence the formation of attitudes and prejudices, which in turn can have an influence on coexistence and social cohesion.

To address the problem in a practical way, we employed a scale similar to those used by Blank and Schmidt (Reference Blank and Schmidt2003), Davidov (Reference Davidov2009), or Huddy, Del Ponte, and Davies (Reference Huddy, Del Ponte and Davies2021), which allows us to classify participants according to their degree of nationalism: High Nationalism and Low Nationalism (similar to Hassin et al. Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007). These categories correspond to more or less exclusionary attitudes. In this way, we can analyze whether exposure to the chosen visual stimuli, in this case flags and emoticons, have exclusionary effects in relation to the Catalan conflict.

Although the influence of national symbols in the emotional state is assumed, as we can see in a military commemoration or a sporting event, there are no experiments that analyze in what way they do that or how much they alter or provoke emotional reactions. With the experiments described below, we have tried to discover whether the Spanish flag arouses emotional states similar to those elicited by widely used symbols as emoticons. First, similarly to Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Enders-Comberg, Wagner, Christ and Butz2012), Butz et al. (Reference Butz, Plant and Doerr2007), Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007), Sibley, Hoverd, and Duckitt (Reference Sibley, Hoverd and Duckitt2011), and other studies, we try to find out if the Spanish flag affects the political opinions of citizens. Second, we will analyze what kind of emotions the Spanish national symbol builds, if any. In this way, we can find out if it produces a positive or negative emotional state. That is, whether it generates inclusive or exclusive attitudes.

However, we do not know if the flag’s emotional effect has a positive or negative effect. We propose a simple way to measure if the flag’s emotional effect is a positive or negative one or has high or low arousal: to compare with the exposition to other visual stimuli directly linked to emotions, such as emoticons (that are emotional catalysts).

The use of emoticons in the experiments is intentional. Facial expressions provide the subject with information about the emotional state of the person with whom he interacts (Ekman, Friesen, and Ellsworth Reference Ekman, Friesen and Ellsworth2013). This information can be replaced by emoticons, which are schematic representations of faces we use to express an emotion. They are part of our lives, mainly thanks to the widespread use of messaging services or social networks (Derks, Bos, and von Grumbkow Reference Derks, Arjan and von Grumbkow2008; Comesaña et al. Reference Comesaña, Soares, Perea, Piñeiro, Fraga and Pinheiro2013).

The increasing use of emoticons has aroused the interest of researchers (Tian et al. Reference Tian, Galery, Dulcinati, Molimpakis and Sun2017; Weiß et al. Reference Weiß, Gutzeit, Rodrigues, Mussel and Hewig2019; Zerback and Wirz, Reference Zerback and Wirz2021). Users show great skill in identifying the emotions they seek to communicate with emoticons (Derks, Bos, and von Grumbkow 2008; McDougald, Carpenter, and Mayhorn Reference McDougald, Carpenter and Mayhorn2011; Tian et al. Reference Tian, Galery, Dulcinati, Molimpakis and Sun2017). Moreover, although there may be cultural differences in the interpretation of their meanings, there is a consensus in the allocation of the most basic emotions: joy, sadness, and anger (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Wallbaum, Wasmann, Heuten and Boll2017; Cheng Reference Cheng2017; Takahashi, Oishi, and Shimada Reference Takahashi, Oishi and Shimada2017).

The nonconscious exposure to emoticons can also produce the same psychophysiological reactions as any other visual stimulus (Yuasa, Saito, and Mukawa, Reference Yuasa, Saito and Mukawa2011; Wall, Kaye, and Malone, Reference Wall, Kaye and Malone2016; Weiß et al., Reference Weiß, Gutzeit, Rodrigues, Mussel and Hewig2019). That is why we consider the use of emoticons as a way to instill a particular emotional state in the subject. The use of a subliminal stimulus that includes an emoticon can alter the emotional state of the viewer in the wanted direction. Once we achieve the alteration of the viewer’s emotions, we expect he changes his political views accordingly. With the second experiment, we will show that political opinions change depending on the emoticon the subject has perceived unconsciously. Therefore, we can compare the consequences of flag exposure and emoticons exposure. We will be able to verify if the flag arouses the same emotional reaction as the emoticons. So we can examine whether the widespread presence of the Spanish flag, due to the problem posed by the Catalan independence movement, builds a public emotional estate and its nature.

Experiments

The presence of flags in public spaces is associated with specific emotions. That is clear in a state funeral, a military parade, or a sporting success celebration. These rituals build a relationship between political objects and the emotions aroused in these events. However, we have doubts about what the prevalent emotions are and whether they have any specific behavior linked to them.

In our opinion, the changes in political behavior produced by exposure to the flag are directly related to somatic markers. That exposure arouses an emotional response that allows us to analyze whether exposure to objects of nonconscious perception, such flags sometimes, influence the emotions of individuals. Our study is not limited to analyzing whether emotions change; it also allows us to observe whether those changes are capable of modifying our political opinions.

To analyze the effects that exposure to the flag, even in an unconscious way, has on the emotions, we carried out two experiments, following the methodology applied by Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Kardosh, Porter, Carter and Dudareva2009), Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007), and Ferguson and Hassin (Reference Ferguson and Hassin2007). First, we expose, in a subliminal way, the participants to the flag of Spain. In this way, we will be able to observe if there are effects in their behavior measured in the variability that they offer to a series of questions of political content. The questions will focus on opinions related to the territorial crisis produced by Catalonia’s attempt at independence. We hope these series of items will allow us to classify their responses as patriotic or nationalistic—that is to say, an inclusive or an exclusive reaction that will provide us with a first classification of the effects produced by exposure to the flag of Spain.

In a second experiment, we will expose the participants, subliminally, to happy, sad, and neutral emoticons. In this way, we can first observe whether these visual objects are capable of influencing our emotions and behavior, as previous research has shown. Second, we can compare those possible effects with the results of Experiment 1.

The contrast between Experiments 1 and 2 will allow us to obtain a series of relationships between emotional reactions and exposure to a flag or to an emoticon, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Expected Relationships between Emotions and the Exposure to a National Flag or to an Emoticon

Subliminal elicitation of emotional political reactions

There is a large amount of research about the exposure to stimuli that are not consciously perceived by the individual, although the results are not always unanimous. Even if some scholars had discarded the effects of subliminal stimuli (that is, stimuli that occur below the threshold of conscious perception, as Broyles Reference Broyles2006; Grimes Reference Grimes2010; Nelson Reference Nelson2008), there are a great number of experiments that show real effects, especially in marketing research. For example, It has been shown how restaurant’s decoration influences food choosing (Jacob, Guéguen, and Boulbry Reference Jacob, Guéguen and Boulbry2011) or how religious symbols affect altruistic donations (Guéguen, Bougeard-Delfosse, and Jacob Reference Guéguen, Bougeard-Delfosse and Jacob2015).

The possibility that a subliminal stimulus may influence the behavior of subjects remains open to debate in both experimental psychology and cognitive neuroscience (Sperdin et al. Reference Sperdin, Spierer, Becker, Michel and Landis2015). However, as the last study stated, the EEG (electroencephalogram) or fMRI (por functional magnetic resonance imaging) has detected responses in subjects exposed to visual stimuli that cannot be consciously perceived (Sperdin et al. Reference Sperdin, Spierer, Becker, Michel and Landis2015; Weiß et al. Reference Weiß, Gutzeit, Rodrigues, Mussel and Hewig2019). Other findings open new lines of research linked to the potential that the use of subliminal stimuli may have to alter the behavior of consumers. A growing number of experimental data show that subliminal effects are reproducible ones, which helps to end skepticism about them (Gibson and Zielaskowski Reference Gibson and Zielaskowski2013).

Subliminal stimuli can positively change some evaluations (Dijksterhuis, Reference Dijksterhuis2004), adjust the response that occurs in a sequence of words coherent with the stimuli (Draine and Greenwald Reference Draine and Greenwald1998), or even modify the evaluation of political candidates (Weinberger and Westen Reference Weinberger and Westen2008). Research has advanced too into the possible adjustment of behavior, and not only of judgments or opinions (Gibson and Zielaskowski Reference Gibson and Zielaskowski2013). Research suggests that the activation of a mental construct through a stereotype can cause behavior that is consistent with the individual’s previous construct (Dijksterhuis and Bargh Reference Dijksterhuis and Bargh2001). This process is known as “hot cognition” (Fazio et al. Reference Fazio, Jackson, Dunton and Williams1995; Redlawsk Reference Redlawsk and Redlawsk2006). This kind of exposure can activate “trait concepts,” which are a network of meanings, values, or feelings that allow the subject to offer a coherent response to them (Bargh, Chen, and Burrows Reference Bargh, Chen and Burrows1996; Kam Reference Kam2007). For example, even if the flag is just a piece of cloth, its exhibition activates a series of representations, meanings, or emotions (trait concepts) capable of modifying subjects’ behavior, but only in a coherent way with previously learned patterns (Janssen and Verheggen Reference Janssen and Verheggen1997; Erisen, Lodge, and Taber Reference Erisen, Lodge and Taber2014).

We choose to employ subliminal priming in our research because, as it has been said before, this kind of symbol (flag) is unconsciously perceived. Citizens accustomed to seeing it almost continually do not notice their presence. Even more important, participants in the experiment are unaware of the research objectives. We avoid that they can consciously control their responses or activate social desirability bias (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2004; Kam Reference Kam2007). In addition, it is the easiest way to access hot cognition and determine the degree of influence that the emotional response has on their behavior and opinions (Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000). Besides, the use of emoticons (Experiment 2) allows us to analyze the effectiveness of these visual stimuli in creating emotional states. We check not only whether they influence the behavior of the participants but also the way in which they do it. It is an interesting methodological innovation in the field of the study of emotions.

Sample size and statistical power

In Experiment 1, an effect size of f = 0.4 would provide a power of 0.80, α = .05, and equal N across groups; a G*Power analysis specified 51 participants per two conditions (priming and control). In Experiment 2, an effect size of f = 0.3 would provide a power of 0.80, α = .05, and equal N across groups; a G*Power analysis specified 111 participants per three conditions (happy, sad, and neutral). Finally, there were 85 participants in Experiment 1 and 126 in Experiment 2.

We recruited participants among undergraduate students (in political science, sociology, and international relations). All participants had Spanish nationality. The experiments were in a laboratory. Each participant did it individually. In Experiment 1, the recruitment campaign was not completely successful. Some of the registered participants did not attend the laboratory on the day of your appointment (n = 85). For this reason, in Experiment 2 we planned to overrepresent the sample with a larger campaign. Finally, we conducted 126 successful experiments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The remaining details of the samples and experiments are in the section of each experiment.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was designed to test the effect of subliminal exposure to Spain’s national flag on political opinions regarding the nationalist conflict with Catalonia. By asking participants to answer questions about sensitive and polemical aspects like the convenience of a negotiation between the central government and the Generalitat or the inclusion of Catalan football players in Spanish national team, we were able to analyze whether individuals who were exposed to the Spanish national flag made more negative judgments about these issues, independent of their previous political attitudes. We anticipated that participants exposed to the flag would report a lower degree of nationalist attitudes. This will show that subliminal priming can prompt notable changes in expressed political opinions.

Method

Participants. The data for this study were collected in seven sessions at a Public University. Eighty-five undergraduate students (45 females; everyone answered the question on gender) in final political science courses took part in the experiment as a voluntary activity. They were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions of the study: control group (41 participants, 22 females) or priming group (44 participants, 24 females).

Procedure

The procedure followed across all sessions was identical. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were assigned an individual cubicle with a computer. They were informed that they would take part in an experiment to measure their attitude on different political issues and that all the recollected data will be anonymous. The experimenter gave a verbal overview of the procedure and accurate information about the process that participants had to follow to answer the questions. The instructions were clearly presented through an example before the experiment started.

The experiment proceeded in three different stages: first, participants had to answer a two-item questionnaire to score their identification with Spanish nationalism (the questions were obtained from the International Social Survey Program 2013, see Appendix 2). In this phase of the experiment, they were asked if they wanted to give information about their gender. Following this questionnaire, they were presented with a simulation of the final one.

The simulation showed different random sentences without any relation to the main subject of the experiment. Before each of the sentences appeared on the computer’s screen, participants had to guess if they would appear in its upper or lower part. In order to do this, they were presented with a stimulus in the center of the screen, which gave them a clue about where the sentence will appear. The clue was an arrow that went rapidly up or down (see Appendix 1). They were then asked to answer to the stimulus through the arrow keys in the keyboard. When the participants pressed the key, the sentence appeared in its location. Whether or not the participant guessed the location correctly was unrelated to the working process of the software. They had to repeat the process with fifty different sentences. The process was designed to force the participant to look at the screen attentively to ensure that the subliminal stimulus was unconsciously perceived.

These simulations or practice tasks were designed to expose participants to the subliminal visual stimulus that was intended to prime the Spanish national flag, shown in Appendix 1. As in Hassin et al.’s (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007) experiment, the complete visual stimuli were flashed for 300 milliseconds. The flag was exposed for 16 milliseconds in the middle, preceded and followed by the moving arrow. In the control condition, the flag was replaced by a control stimulus that showed a distorted Spanish flag (see Appendix 1) in the same way and for the same time. So, all the participants were primed 50 times before they could answer the real questionnaire.

The following task was to answer the questions of the real experiment (see Appendix 2). Questions were shown on the computer screen in the same way as were the previous sentences. The participants had to guess if the question would appear in the upper or lower region of the screen after a visual clue that contained the subliminal stimulus. They were presented with 20 questions, 10 of them related to the Catalan independence conflict. The other 10 were related to other political and nonrelated issues. The participants had to give a numerical answer through the keyboard to proceed. They had to show to what degree they agreed with the assertion shown on the screen through a numerical scale that ranged from one extreme attitude to another: from 1, which meant complete disagreement to 9, which meant complete agreement. To avoid any possibility of ambiguity, the instructions and the meaning of the scale were shown in the middle of the screen each time an assertion appeared. All the questions were randomly presented to avoid that their order could influence the answers of the participants.

Finally, everyone had to answer a questionnaire about the experiment. They were asked (1) what kind of stimuli they had seen before the sentences or questions appeared, (2) if there was more than one stimulus, (3) what were those stimuli if they saw more than one, (4) if they thought that there was any relationship between the stimuli and the questions, (5) if they had developed and followed any strategy to answer the questions, and (6) what they thought the experiment wanted to discover or was about. The purpose of this last questionnaire was to measure the awareness of the participants of the subliminal priming.

Results

None of the participants, in the control tests, indicated the presence of any subliminal prime. Most of them only reported the presence of a stimulus before each question: the arrows (the mask). The participants considered that it was a research about the use of social networks, the effects of information on political behavior or the general situation of the country. None of them declared that it was an analysis of the effects of the Spanish flag. For these reasons, we use the data of all the participants in the experiment.

Political Stance

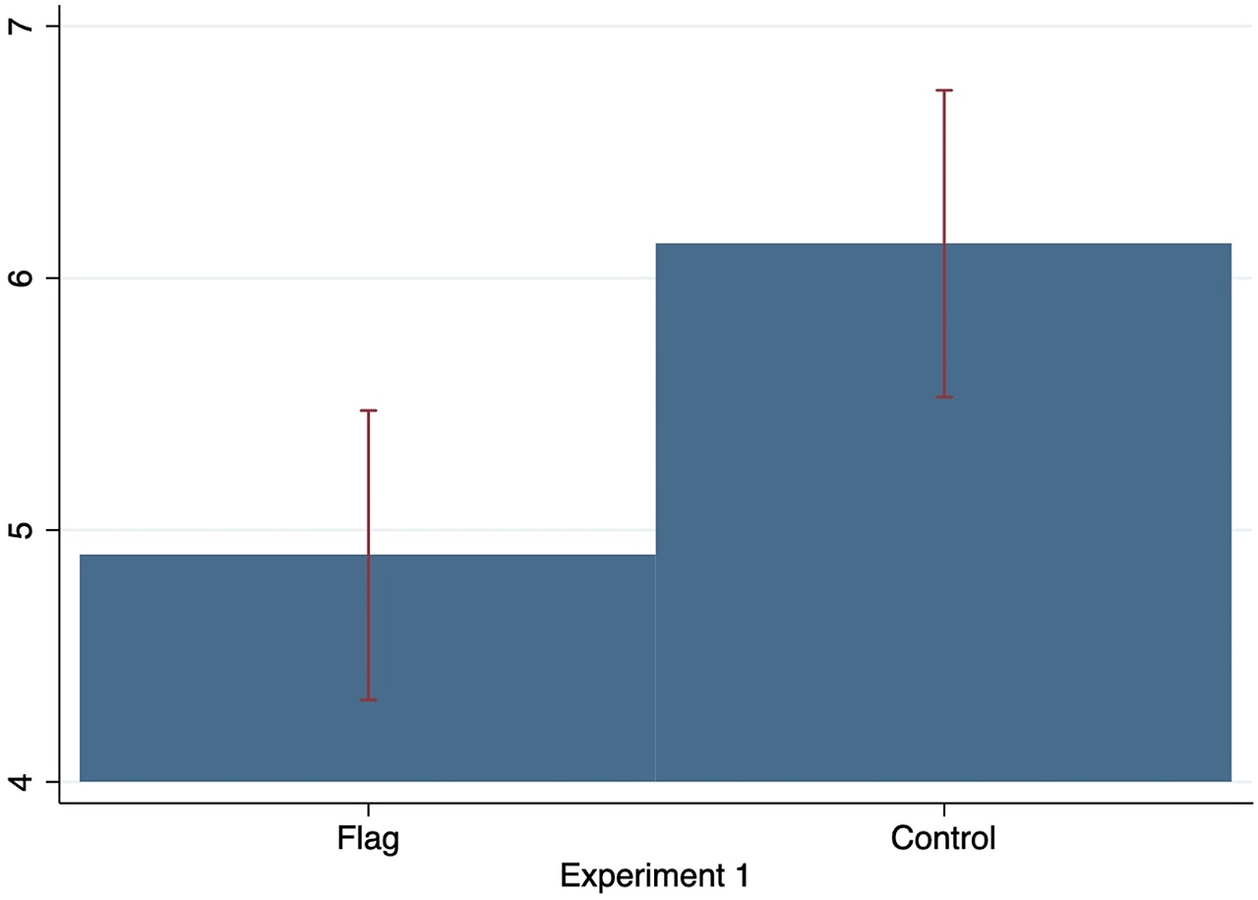

The data obtained in the two groups, control (n = 41) and priming (n = 44), have a normal distribution and have passed the usual hypothesis tests. The political responses of the participants are strongly correlated (Cronbach’s α = 0.897). The control group gets more exclusive responses (M = 6.13, SD = 1.92) than the group exposed to the flag (M = 4.90, SD = 1.88): t(83) = 2.985, p < 0.004 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean correlation in Experiment 1 for each trial type (Flag and Control). Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Following the methodology described by Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007), we classified our participants by their answers to the questions about their level of nationalism. Thus, we divided them into two groups: High Nationalism (HN) and Low Nationalism (LN). Traditionally, Spanish nationalism has been linked to conservative political ideologies. Probably, higher levels of nationalism will indicate less tolerant responses and a greater degree of disapproval with the pro-independence. On the contrary, the lower levels of nationalism will be associated with more tolerant responses with a more moderate position.

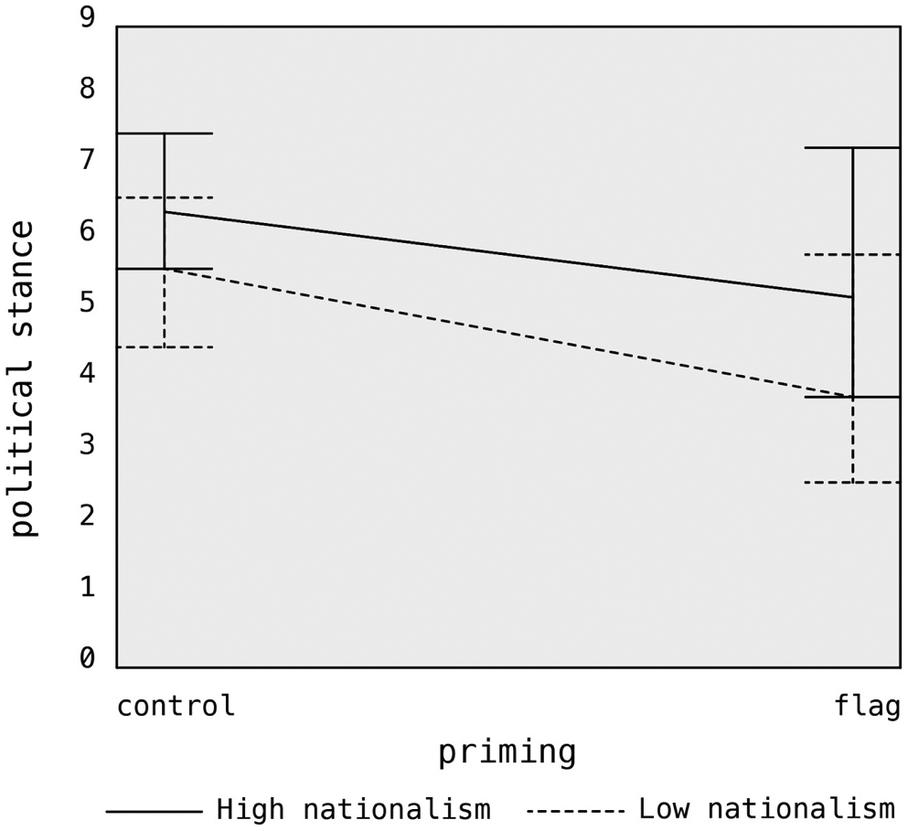

With the average of the political questions, we have executed an analysis of variance ANOVA with four groups as a classification variable. These factors are the product of the crossing of the groups of control and priming and High Nationalism and Low Nationalism (2 × 2).

As expected, there is a significant interaction between priming and nationalism: F (3, 81) = 5.280, p < 0.002, η² = .164. In the control group, participants who were in the Low Nationalism group (M = 5.60, SD = 1.47) expressed opinions very different from those in the High Nationalism group (M = 6.44, SD = 2.11): t(24) = 2.889, p < 0.01. However, the use of priming didn’t influence the answers of both groups. Although it produced effects, they are not as strong as in the case of Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007). In Hassin et al.’s experiments with the flag of Israel, the distance between High Nationalism and Low Nationalism participants was reduced from 3.4 to 0.31 points and both groups converged to the center of the scale. In our case, the stimulus of the flag of Spain moderated the responses of participants with High Nationalism (M = 5.24, SD = 1.88) and Low Nationalism—(M = 3.87, SD = 1.57): t(57) = 2.308, p < 0.03—but it didn’t significantly reduce the distance between the two groups (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average responses to questions about Catalan independence as a function of priming and nationalism questionnaire (high numbers denote more nationalistic attitudes).

In the study by Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007), it was observed that the Israeli flag activates what the authors call civic patriotism in the participants and what we refer to in this article simply as patriotism. This activation helps to reduce the exclusivity of nationalism and to improve relationship with out-groups and minorities in addition to increasing the importance of civic values (Kosterman and Feshbash Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Schatz, Stau, and Lavine Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999; Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003; Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004; Skitka Reference Skitka2005; Takeuchi et al. Reference Takeuchi, Taki, Sekiguchi, Nouchi, Kotozaki, Nakagawa, Miyauchi, Iizuka, Yokoyama, Shinada, Yamamoto, Hanawa, Araki, Hashizume, Kunitoki, Sassa and Kawashima2016; Huddy, Del Ponte, and Davies Reference Huddy, Del Ponte and Davies2021). However, it seems that this is not the case for the Spanish flag. We believe that the response produced by the Spanish flag is consistent with the participant’s prior beliefs. However, in our experiment there is not as pronounced a convergence toward more moderate positions as in Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007). The Spanish flag does not provide such a prominent corrective effect. This may be because, in our case, although its ability to activate prior beliefs is demonstrated, they are not of the same type as the Israeli flag.

Probably, the difference in the results is due to the associative network that is built around the Spanish flag and that is activated when it is displayed. Although Spanish identity is related to nationalism (Davidov Reference Davidov2009), due to the ethnic composition and history of Spain it is not an essentialist type of nationalism (Moreno, Reference Moreno2020).

The nonessentialist nature of Spanish nationalism can be attributed to the historical evolution of the Spanish nation. According to Álvarez Junco (Reference Álvarez Junco2016) or Solé Turá (Reference Solé Turá1989), the national construction of Spain coincided with the emergence of imperial monarchy in the 15th century. The monarchy made agreements with other regions, which were submitted to the Crown in exchange for recognition and autonomy. This means that there was no monotheistic view of the nation and there was no active process of reducing identity diversity. Therefore, Spain does not fit into the category of a nation-state and is closer to what authors like Moreno call a Union-State: a political entity formed by different parts that come together through agreements and treaties under the legitimacy of the Crown.

During the Franco dictatorship (1939–1975), a centralizing process took place that attempted to redefine national identity. Along with an essentially Catholic component, this national construction was based on the linguistic castilianization of the State (Raja-i-Vich Reference Raja-I-Vich2020). However, the absence of a true ethno-territorial homogenizing impulse meant that this centralizing process lacked sufficient strength to become a Staatsvolk, or core nation. This interlude ended with the beginning of the new democratic period, the Constitution of 1978, and the establishment of the Estado de las Autonomías.

Since 1978, the Spanish territorial organization and its national conception have been configured by a constitutional singularity: the recognition of the existence and autonomy of nations and regions. Spain is established as a plurinational state where different ethno-territorialities coexist. This coexistence is articulated based on solidarity, and any potential conflicts have a more political than cultural nature (Moreno Reference Moreno, Burgess and Pinder2007). The absence of a monistic or essentialist view has enabled the creation of a dual identity that allows for the coexistence of a regional (ethno-territorial) and a national (state) identity. This kind of nationalism lacks exclusionary factors that characterizes essentialist nationalism and prevents the attitudes against minorities or outgroups (Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004; Pehrson et al. Reference Pehrson, Vignoles and Brown2009) that appear, for example, in the German case (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Enders-Comberg, Wagner, Christ and Butz2012).

We can see the moderating effects of priming in High Nationalism if we review the answers to some of the political questions. For example, in the question about supporting the boycott of products of Catalan origin, the control group showed a more belligerent position (M = 6.61, SD = 2.88) than the priming group (M = 3.81, SD = 2.90): t(57) = 3.657, p < 0.001. We also observe how the support for a Spanish veto upon entry into the European Union of a hypothetical Catalan state is reduced between the control group and the priming (M = 6.80, SD = 2.70 and M = 5.27, SD = 2.43, respectively): t(57) = 2.259, p < 0.03.

These effects are more visible in Low Nationalism. Support for the construction of an independent Catalan state, for example, is high in the control group (M = 6.06, SD = 2.49), but it is reduced to almost half in the priming group (M = 3.63, SD = 2.73): t(24) = 2.360, p < 0.03. We find a more intense effect than in the High Nationalism that can also be observed in the support to the prison sentences (hypothetical) for the politicians responsible for the referendum (M = 6.26, SD = 2.34 in the control group; M = 3.63, SD = 2.97 in the priming group): t(24) = 2.523, p < 0.02.

The results of Experiment 1, as had happened in previous research, show the moderating effect of the flag, although these are not as strong in terms of inclusiveness as in the studies of Hassin et al. (Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Shidlovski and Gross2007) or Butz et al. (Reference Butz, Plant and Doerr2007).

The results of Experiment 1 show the influence of exposure to flags on the opinions of the participants. However, we cannot know if it is due to a change in their emotions. Nor is it possible to discover if the emotional reaction, if any, is a positive or a negative one. In the same way, we do not know if emotions are capable, by themselves, of changing the opinions of the participants on political issues. For this reason, as advanced, in Experiment 2, we will test an experimental technique to reproduce positive and negative emotions in the participants and observe their effects.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to replicate different moods and analyze their influence on political opinions. The procedure was the same as that for Experiment 1: we asked participants to answer the same questionnaire about sensitive and polemical aspects linked to the Catalan independence process (see Appendix 2). We were able to analyze whether the exposure to an emoticon (Happy, Neutral, or Sad) could affect the judgments about these issues, independent of their previous political attitudes. Regardless of its positive or negative valence, mood is expected to produce congruent behavior. (Marcus Reference Marcus2000; Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Ottati, Burns and Redlawsk2006; Spezio and Adolphs Reference Spezio, Adolphs, Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2007; Forgas Reference Forgas2013; Matovic, Koch, and Forgas Reference Matovic, Koch and Forgas2014; Karnaze and Levine Reference Karnaze, Levine and Lench2018). We expected that participants exposed to a happy emoticon would report a lower degree of disapproval of the Catalan independence process. Inversely, the participants exposed to the sad emoticon will report an increasing rejection of Catalan nationalist claims.

Method

Participants

The data for this study were collected in eleven sessions at a Public University. One hundred and twenty-six undergraduate students (n = 67 females; everyone answered the question on gender) in final political science courses took part in the experiment as a voluntary activity. They were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions of the study: neutral priming group (Neutral emoticon) (n = 40, 22 females), positive priming group (Happy emoticon) (n = 42, 23 females), or negative priming group (Sad emoticon; (n = 44, 22 females).

Procedure

The procedure across sessions followed the same steps described for Experiment 1. In this case, we exposed participants to a subliminal visual stimulus that primed a Happy, Neutral, and Sad emoticon (see Appendix 1). The complete visual stimuli were flashed for 300 milliseconds. The emoticon was exposed for 16 milliseconds in the middle, preceded and followed by the moving arrow. In the control condition, the emoticon had no emotional expression (see Appendix 1). As in the previous experiment, all the participants were primed 50 times before they could answer the real questionnaire, which was the same as in Experiment 1. The rest of the procedure followed exactly the same path described earlier in our first experiment.

Results

The experiment was successful. The use of subliminal stimuli achieves its objectives. None of the participants noticed the presence of priming. In the subsequent control tests, they didn’t indicate the presence of any type of stimulus, sign, or symbol. As in Experiment 1, the participants believed that the research focused on the connection between social networks and information, the political situation in Spain, etc. No answer matched the true purpose.

Therefore, all data collected were used in the analysis.

Political Stance

The sample (n = 126) was classified into three groups: Happy (n = 42), Neutral (n = 40, and Sad (n = 44). The data had a normal distribution and passed the usual hypothesis tests. The political responses of the participants have a strong correlation (Cronbach’s α = 0.926).

Before starting the tests, we expected that, in political questions, the emoticons get different degrees of acceptance: more positive (inclusive) with Happy and Neutral and more negative (excluding) with Sad. To observe the interaction between emoticons and nationalism, as we did in Experiment 1, we divided the participants into two groups: Low Nationalism and High Nationalism. We wanted to observe whether the effects are as expected as with the use of the flag (moderation and convergence of the values) or, on the contrary, whether the emoticons produce other effects.

First, with the average of the political answers, we executed an analysis of variance to analyze the general effects of the emoticons. We detected significant effects between the emoticons and the perception of political problems. Happy received more moderate and homogeneous ratings (M = 4.70, SD = 1.59) than Neutral (M = 5.19, SD = 2.10). The worst assessment was offered by participants who were primed with the Sad emoticon (M = 6.52, SD = 1.72): F (2, 123) = 11,682, p < 0.00, η² = .160 (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mean correlation in Experiment 2 for each trial type (Happy, Neutral, and Sad). Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

The participants in the Low Nationalism group showed similar behavior in the distribution of their answers (moderate vs. excluding). In addition, for the Happy (M = 3.51, SD = 1.23), Neutral (M = 3.84, SD = 1.54), and Sad (M = 5.68, SD = 1.48) emoticon results, the distance between the two most opposite groups increased: F (2, 38) = 8.979, p <0.001, η² = .321. The result, as in the case of the Spanish flag, could be related to activation of latent nationalist attitudes that, in this case, are not caused by the presence of national symbols. The most excluding attitudes are generated by a negative mood (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Average responses to questions about Catalan independence as a function of priming and nationalism questionnaire (high numbers denote more nationalistic attitudes).

A post hoc analysis (Scheffe and Bonferroni) indicated a significant interaction between the Happy and Sad and Neutral and Sad emoticons (not between Happy and Neutral). For this reason, a t-test was performed, which indicated a significant relationship between the first—t(25) = 4.105, p < 0.00—and the second—t(26) = 3.213, p < 0.003. Therefore, the Sad and Low Nationalism combination is more efficient for creating states of mind that influence the political perception of the participants.

Sad emoticon’s ability to influence opinions can be observed in the increase of the excluding positions in many of the questions. The emotional response created by this emoticon radicalizes less nationalist subjects. For example, asked about the possibility that the Spanish State negotiates with the separatist, Happy priming gets a more moderate position rating (M = 4.00, SD = 1.47) compared with Sad priming (M = 5.71, SD = 1.38): t(25) = 3.121, p < 0.005.

It’s also interesting to observe the effects of emoticons on the most nationalist participants (High Nationalism). A priori, with more nationalist positions we could expect moderating effects with the use of the Happy emoticon. The result obtained behaves as expected (optimism vs. excluding). Happy (M = 5.24, SD = 1.44) achieved a more moderate result in political questions than Neutral (M = 5.92, SD = 2.01) and Sad (M = 6.92, SD = 1.71): F (2, 82) = 7.100, p < 0.001, η² = .148.

The Happy emoticon moves participants to more moderate positions. However, it seems that the effect of emoticons is less pronounced in more nationalist participants. A Post hoc analysis revealed, mainly, a statistically significant interaction between the Happy and Sad emoticons: t(57) = 4.061, p = 0.00. There are few questions in which the three emoticons produce significant effects. For example, in the question about the hypothetical veto of the entry of Spain in Catalonia in the EU, there is a greater interaction between Happy (M = 4.96, SD = 2.17), Neutral (M = 6.92, SD = 2.229), and Sad (M = 7.00, SD = 2.13): F (2, 82) = 7.895, p < 0.001, η² = .161.

The results indicate that the basic emoticons (Happy and Sad) produced changes in the mood of the participants. In line with previous studies (Marcus Reference Marcus2000; Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Ottati, Burns and Redlawsk2006; Spezio and Adolphs Reference Spezio, Adolphs, Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2007; Forgas Reference Forgas2013; Matovic, Koch, and Forgas Reference Matovic, Koch and Forgas2014; Karnaze and Levine Reference Karnaze, Levine and Lench2018), the positive or negative valence of the changes has induced congruent judgments, more moderate or exclusive, on different political items. These effects are more relevant in the participants exposed to the sad emoticon. There is an effect similar to that of research such as Gasper and Danube (Reference Gasper and Cinnamon Danube2016), Gur, Ayal, and Halperin (Reference Gur, Ayal and Halperin2020), Long and Brecke (Reference Long and Brecke2003), or Petersen (Reference Petersen2002), who relate this state of mind to the reduction of interest in negotiation and the issuance of negative judgments against the external group.

Thus, for example, support for a hypothetical negotiation of the independence of Catalonia receives greater approval in Happy priming group (M = 4.85, SD = 1.82) than in the Sad group (M = 3.06, SD = 1.73): t(84) = 4.661, p < 0.00. The division between Happy-Inclusive and Sad-Excluding affects Low Nationalism, presumably more tolerant (Happy: M = 6.00, SD = 1.47; Sad: M = 4.28, SD = 1.38): t(25) = 3.121, p < 0.005—but it has a greater influence on High Nationalism. In this group, the Happy emoticon (M = 5.65, SD = 1.75) is able to moderate the political position of the subjects, presumably more belligerent, and the Sad emoticon intensifies the rejection to the negotiation (M = 7.50, SD = 1.59): t(57) = 4.228, p < 0.00.

General Discussion

The experiments were successful. Both tests succeeded in modifying the opinions of the participants through exposition to subliminal stimuli, due to the activation of previous associations (Kam Reference Kam2007) or trait concepts (Bargh, Chen, and Burrows, Reference Bargh, Chen and Burrows1996). They produce changes in the opinions according to the stimuli shown (Dijksterhuis and Bargh Reference Dijksterhuis and Bargh2001).

The national flag is probably the most relevant political symbol. It not only represents the country but also has a series of meanings capable of conditioning the political behavior of citizens (Kemmelmeier and Winter Reference Kemmelmeier and Winter2008). In our research, the Spanish flag showed its effectiveness as a subliminal stimulus when it comes to influencing the opinions of the participants. However, it had a lower effect than that obtained in previous experiments (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Enders-Comberg, Wagner, Christ and Butz2012; Ferguson and Hassin Reference Ferguson and Hassin2007; Hassin et al. Reference Hassin, Ferguson, Kardosh, Porter, Carter and Dudareva2009; Sibley, Hoverd, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Hoverd and Duckitt2011). Furthermore, despite the moderation in responses to critical political questions, it is difficult to determine whether their effects bring the Spanish flag closer to patriotism or nationalism—that is, whether it generates more exclusionary or inclusive behavior. Similar to research such as that of Skitka (Reference Skitka2005), overexposure to flags in a crisis situation did not lead to an increase in more exclusionary nationalism. This may be due to the very configuration of Spanish national identity. The nonessentialist character of the Spanish nation (Moreno Reference Moreno2020), does not generate such exclusionary attitudes (Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004; Pehrson et al. Reference Pehrson, Vignoles and Brown2009).

The relationship between the participants’ changes in opinion and the emotions they experience was sufficiently tested in Experiment 2. Emoticons, used as objects of nonconscious perception, were able to reproduce elemental emotions (happy/sadness) and change the political opinions of the participants. Their responses have allowed us to analyze the effect of emotions on citizens’ political ideas in an innovative way.

Despite the success of the experiments, it is necessary to be cautious regarding the results obtained. Although the moderating effects of the Spanish flag, similar to Neutral or Happy emoticons, are the most characteristic mark, these occurred under laboratory conditions, months after the Catalonia declaration of independence. We cannot assure that, throughout the political crisis with the Catalan separatists, the use of the flag would have obtained a comparable response. In spite of this, the statistical significance and its similarity with the emoticons’ effects show the interest of the findings.

The results of the experiments described above did not allow us to classify unequivocally the type of emotion produced by subliminal exposure to the flag of Spain. Although behavior in political responses brings it closer to a neutral or happy position, one of the most relevant conclusions of this study is that emoticons produce a much more intense type of response than flags as political objects.

The absence of specific political meanings associated with flags does not, however, prevent emotions from affecting the mood of the participants in their political evaluations. This fact appears maybe because it is about a purely emotional change, free from political socialization, and, therefore, emotions are much more intense in their effects.

Emotions have effects on behavior even when they are not consciously available (Öhman, Flykt, and Lundqvist Reference Öhman, Flykt, Lundqvist, Lane and Nadel2000; Winkielman and Berridge Reference Winkielman and Berridge2004; Zemack-Rugar, Bettman, and Fitzsimons Reference Zemack-Rugar, Bettman and Fitzsimons2007). As we have seen in Experiment 2, stimuli, even subliminal ones, capable of generating emotions can produce changes in our mood that, in turn, provide congruent behavioral responses (Karnaze and Levine Reference Karnaze, Levine and Lench2018; Marcus Reference Marcus2000; Spezio and Adolphs Reference Spezio, Adolphs, Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2007). These effects are most evident with negative stimulation, which reduces interest in negotiation and increases negative judgments against the out-group. (Danube Reference Gasper and Cinnamon Danube2016; Gur, Ayal, and Halperin Reference Gur, Ayal and Halperin2020). In the case of our participants, this negative reaction could be encouraged by the activation of stereotypes against Catalans. Although we cannot determine whether this occurred, the results could be consistent with findings such as those of Clore and Huntsinger (Reference Clore and Huntsinger2007), who consider that the attribution of stereotypes is able to inhibit egalitarianism and increase the rejection of out-group.

The results of this research suggest that it is possible that the “Spain of the balconies” may have influenced the opinions of citizens. The flag of Spain is a political object capable of producing emotional responses. Therefore, their constant exposure could influence the construction of the public mood. The positive or negative valence of this public mood and the effects it can generate on the political opinions of citizens will depend on the significance attributed to the flag and the political issue being evaluated. For this reason, we believe that the results that can be obtained with other flags and other political issues will be different.

The experiments carried out have allowed us to deepen our knowledge of the effects of political objects of nonconscious perception. Besides, we present an original methodological contribution: the use of emoticons to alter political views. This contribution could be relevant in the areas of political behavior and political psychology, mainly in everything that has to do with the relationship established between emotions and politics or the effects of political communication, especially in everything relative to negative campaigns. It also opens new avenues for further thinking on the relationship between nationalism and emotions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2023.62.

Data availability statement

Data available at Open Science Framework doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/RFHU4.

Financial support

Funding for APC was provided by Read and Publish Consortium Madroño 2023.

Competing interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosure

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.