Introduction

Studying in university is an important life stage during which a person moves from family dependence to independence and socialisation. The transition is challenging because of the high level of academic and employment stress and the prevalent interpersonal, romantic and emotional problems in this particular stage for university students (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Selman and Haste2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Cao, Fang, Deng, Chen, Lin, Liu and Zhao2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu and Zhong2020a). However, due to China's strict examination-oriented education system, many university students have little training in interpersonal communication, problem solving and teamwork skills before entering university. Therefore, this population has difficulties in adapting to the university environment and is more likely to feel unconfident and confused about the future (Kirkpatrick and Zang, Reference Kirkpatrick and Zang2011; Hu, Reference Hu2018). Moreover, university students in China have a high likelihood of experiencing parent−adolescent conflict owing to the popular authoritarian parenting style in the context of Chinese culture, which is characterised by high control and high warmth (Marmorstein and Iacono, Reference Marmorstein and Iacono2004; Diao, Reference Diao2007; Ren and Edwards, Reference Ren and Edwards2015). As a result, Chinese university students are at high risk for common mental health problems; for example, empirical evidence from a systematic review of 39 studies has shown that as high as 23.8% of Chinese university students suffer from depressive symptoms (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Xiao, Liu and Li2016).

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a global mental health crisis. Lessons learned from the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in China suggest that depressive symptoms are one of the most common mental health problems among university students; for example, during the SARS epidemic, 25.4–29.6% of the Chinese university students had depressive symptoms (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Huang, Liu and Li2004; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, Wei and Jia2004). In China, the pandemic has changed many aspects of university students’ daily lives. Despite an increase in time spent with parents, home-isolated students have an increased chance of conflicting with parents (Luo, Reference Luo2020). To prevent the spread of the epidemic, students are not allowed to return to campus to resume their studies, potentially delaying their graduation dates. Furthermore, because of social distancing and stay-at-home requirements, social and peer interactions are reduced, likely resulting in an increased level of social disconnectedness and a decreased level of peer support. Because parent−adolescent conflict, social disconnectedness and a lack of peer support have been associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents (Vaughan et al., Reference Vaughan, Foshee and Ennett2010; Elmer and Stadtfeld, Reference Elmer and Stadtfeld2020; Rognli et al., Reference Rognli, Waraan, Czajkowski, Solbakken and Aalberg2020), the emotional health of Chinese university students may have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental health services and crisis psychological intervention have been an essential part of the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic (Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang, Cheung and Xiang2020a). To facilitate the development of population-specific intervention programmes, it is necessary to understand the epidemiology of depressive symptoms in university students in China amid the COVID-19 pandemic. However, available studies on depressive symptoms among Chinese university students have varied widely in terms of sampling methods, sample sizes and assessments of depressive symptoms, and most importantly, there have been considerable variations in the reported prevalence of depressive symptoms (1.8–79.3%) (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Cui and Zhang2020a; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Wang, Li, Hou, Liu, Hu and Wei2020b), making mental health policy-making and planning difficult. To help clarify this issue, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and the protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the registration number CRD 42020206666.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for eligible studies were (a) cross-sectional surveys or baseline surveys of cohort studies with meta-analysable data (i.e. reporting the prevalence of depressive symptoms); (b) study subjects were Chinese university students, including overseas students and postgraduates; (c) the presence of depressive symptoms was assessed with standardised instruments and (d) the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (since 1 January 2020). We excluded studies with mixed samples that did not present results separately for university students and studies that assessed depressive symptoms with unstandardised instruments (i.e. a simple self-designed question or a self-designed scale without convincing evidence of reliability and validity).

Literature search

We searched potential studies published between 1 January 2020 and 10 February 2021 in both Chinese and English bibliographic databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang data, VIP Information, PubMed, Embase and PsycInfo. Key terms used were: (adolescen* OR teenager* OR youth* OR student* OR young adult* OR undergraduate* OR universit* OR college*), (coronavirus disease 2019 or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 or COVID-19 or COVID) and (depress*). To avoid missing relevant studies, reference lists of the retrieved reviews and included studies were also hand-searched. Preprint servers were also searched to retrieve grey literature: medRxiv, bioRxiv, PsyArXiv, ChinaXiv and Research Square. The literature search was ended on 12 February 2021. Detailed search strategies are provided in online Supplementary Table 1.

Data extraction

By using a predesigned electronic form, the following variables were extracted from included studies: first author, study site, study period, characteristics of the study sample, sampling method, sample size, survey method, assessment of depressive symptoms and rates of depressive symptoms. According to the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China (The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China, 2020), the study period in China was roughly classified as early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak (20 January–20 February 2020), late stage of the COVID-19 outbreak (21 February–28 April 2020) and post-COVID-19 outbreak (since 29 April 2020).

RoB assessment of included studies

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (abbreviated as ‘JBI checklist’ hereafter) to assess the RoB of included studies (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Moola, Riitano and Lisy2014). This checklist evaluates the RoB in terms of nine methodological domains: sample frame, sampling, sample size, description of subjects and setting, sample coverage of the data analysis, validity of the method for assessing the outcome, standardisation and reliability of the method for assessing outcome, statistical analysis and response rate. Two example items of the JBI checklist used in the current study were ‘Was the sample size adequate?’ and ‘Were valid methods used for assessing depressive symptoms?’. Each item has four choices: yes, no, unclear or not applicable. One point is assigned to a ‘yes’ response, and the RoB score is the sum of the nine items, ranging from zero to nine, with a higher score indicating a lower RoB. In this study, the level of RoB of included studies was operationally categorised into low (RoB score of ‘7–9’), moderate (RoB score of ‘4–6’) and high (RoB score of ‘0–3’). A RoB score of nine represents ‘completely low RoB’.

Literature search, study inclusion, data extraction and RoB assessment were independently performed by the first and second authors of this study. They discussed their differences to arrive at a consensus when disagreement occurred in an assessment.

Statistical analysis

We used meta-analysis to generate pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) for the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the whole sample and in various cohorts of the sample. Forest plots were adopted to display the prevalence rates and pooled estimates. We used the I 2 test to evaluate heterogeneity between studies. When there was little evidence of heterogeneity (i.e. I 2 ⩽ 50%, heterogeneity P ⩾ 0.10), a fixed-effect model was used to generate the pooled estimates; otherwise, the random-effect model was used. The pooled rates of various cohorts were compared by using the Z test. We used subgroup analysis to explore the source of heterogeneity in the prevalence estimate of depressive symptoms. The Q-value test was used to test the significance of differences in prevalence rates between subgroups. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plots and Begg's test, since Begg's test is fairly powerful for large meta-analyses that include 75 or more original studies (Begg and Mazumdar, Reference Begg and Mazumdar1994). Before pooled analysis, prevalence proportions were transformed by using the Freeman−Tukey variant of the arcsine square root, Arcsine, untransformed, Log or Logit, as appropriate (Barendregt et al., Reference Barendregt, Doi, Lee, Norman and Vos2013). All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.2). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The process of study inclusion is shown in Fig. 1. Finally, this meta-analysis included 84 studies with a total of 1 292 811 Chinese university students (Cao, Reference Cao2020; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Yuan and Wang2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wen, Chen, Chen, Liu, Lu, Chen, Chen, Shen and Hu2020a, Reference Chen, Liang, Peng, Li, Chen, Tang and Zhao2020b, Reference Chen, Chen, Sun, Hu and Shen2020c, Reference Chen, Qi, Du, Chen and Ren2020d; Chi et al., Reference Chi, Becker, Yu, Willeit, Jiao, Huang, Hossain, Grabovac, Yeung, Lin, Veronese, Wang, Zhou, Doig, Liu, Carvalho, Yang, Xiao, Zou, Fusar-Poli and Solmi2020; Cong et al., Reference Cong, Xiao, Luan, Kang, Yuan and Liu2020; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Wang, Zhu, Liu, Guo, Peng, Shao and Xia2020; Dong, Reference Dong2020; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wei, Mei and Chen2020; Feng, Reference Feng2020; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Zong, Yang, Gu, Dong and Qiao2020; Han et al., Reference Han, Ma, Gong, Hu, Zhang, Zhang, Yao, Fan, Zheng and Wang2020; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Yu, Mou, Chen, Zhao, Zhou, Deng and Yang2020; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, He, Meng, Liu, Zhang, Zou, Zhang, Jiang and Zhou2020; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Liu, Sun, Yuan, Song, Lin, Hu, Yang and Ma2020; Li and He, Reference Li and He2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Lv, Tang, Deng, Zhao, Meng, Guo and Li2020b; Lian et al., Reference Lian, Tan and Zhang2020; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Cui and Zhang2020a, Reference Liang, Zheng and Yu2020b; Lin and Xu, Reference Lin and Xu2020; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Guo, Becker, Yu, Chen, Brendon, Hossain, Cunha, Soares, Veronese, Yu, Grabovac, Smith, Yeung, Zou and Li2020a, Reference Lin, Lin and Jiang2020b; Liu, Reference Liu2020a, Reference Liu2020b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhu, Fan, Makamure, Zheng and Wang2020a, Reference Liu, Yuan and Luo2020b, Reference Liu, Liu and Zhong2020c; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Wang and Liao2020a, Reference Ma, Zhao, Li, Chen, Wang, Zhang, Chen, Yu, Jiang, Fan and Liu2020b; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Luo, Li, Zhang, Wang, Li and Wu2020; Qian, Reference Qian2020; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Li and Zhang2020a, Reference Ren, Wang, Li, Hou, Liu, Hu and Wei2020b; Reference Ren, Chen and Cui2020c; Si et al., Reference Si, Su, Jiang, Wang, Gu, Ma, Li, Zhang, Ren, Liu and Qiao2020; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Lin and Chung2020, Reference Sun, Goldberg, Lin, Qiao and Operario2021; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Hu, Hu, Jin, Wang, Xie, Chen and Xu2020; Wan and Shao, Reference Wan and Shao2020; Wang and He, Reference Wang and He2020; Wang and Li, Reference Wang and Li2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Liu, Jia, Ren and Chen2020b; Reference Wang, Xie and Liu2020c; Reference Wang, Wu and Yu2020d; Reference Wang, Chen, Zhao and Liu2020e; Reference Wang, Yang, Yang, Liu, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Shen, Chen, Song, Wang, Wu, Yang and Mao2020f; Reference Wang, Ding, Jiang, Liao and Li2021; Wei, Reference Wei2020; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tao and Han2020, Reference Wu, Tao, Zhang, Li, Ma, Yu, Sun, Li and Tao2021; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Tan, Sun, Yang, Zhao, Liu, Hou and Hu2020; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Shu, Li, Li, Tao, Wu, Yu, Meng, Vermund and Hu2020a, Reference Xiao, Wang, Xiao and Yan2020b; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Luo, Li, Ge, Xing and Miao2020; Xin et al., Reference Xin, Luo, She, Yu, Li, Wang, Ma, Tao, Zhang, Zhao, Li, Hu, Zhang, Gu, Lin, Wang, Cai, Wang, You, Hu and Lau2020; Xing et al., Reference Xing, Ge, Lu, Shu and Miao2020; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Ming, Zhang, Bai, Luo, Cao, Zhang and Tao2020; Xu and Li, Reference Xu and Li2020; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Zheng, Lin, Xie, Wang and Zheng2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wang, Li, Lei and Yang2020b; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Xu, Zhang, Bu, Cao and Wang2020; Yi et al., Reference Yi, Peng, Zhang and Kong2020a, Reference Yi, Sun and Xie2020b; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Fang and Luo2020, Reference Yu, Tian, Cui and Wu2021; Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Sun, Xie, Wen and Fu2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zeng, Luo, Zou and Gu2020b, Reference Zhang, Liu, Guo, Zhang, Liang, Li and Ni2020c, Reference Zhang, Gao, Yang, Zhang, Qi and Chen2020d, Reference Zhang, Meng, Deng, Huang, Tang, You, Jiang and Duan2020e, Reference Zhang, Jia and Duan2020f, Reference Zhang, Sui and Chang2020g; Reference Zhang, Jing, Wang, Li, Zhao, Yu and Zhang2020h; Zhao and Hu, Reference Zhao and Hu2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Kong, Aung, Yuasa and Nam2020a, Reference Zhao, Kong and Nam2020b, Reference Zhao, Zhang, Zheng, Lian and Huang2020c; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Qi, Wang, Yang, Zhang, Yang and Chen2020; Chen and Zhu, Reference Chen and Zhu2021; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Wang, Liu, Wu, Jiang, Zhou, Zhou and Sha2021; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Zhang, Zhou, Cong, Tao, Han, Hou, Cao and and Zhen2021). Among the 84 studies, seven were preprint articles (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Xiao, Luan, Kang, Yuan and Liu2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu and Zhong2020c; Si et al., Reference Si, Su, Jiang, Wang, Gu, Ma, Li, Zhang, Ren, Liu and Qiao2020; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Ming, Zhang, Bai, Luo, Cao, Zhang and Tao2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jing, Wang, Li, Zhao, Yu and Zhang2020h; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Kong and Nam2020b; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Qi, Wang, Yang, Zhang, Yang and Chen2020), eight had samples recruited from universities at China's COVID-19 epicentre (Hubei or Wuhan) (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Wang, Zhu, Liu, Guo, Peng, Shao and Xia2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhu, Fan, Makamure, Zheng and Wang2020a; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wu and Yu2020d, Reference Wang, Chen, Zhao and Liu2020e; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Wang, Xiao and Yan2020b, Reference Xiao, Shu, Li, Li, Tao, Wu, Yu, Meng, Vermund and Hu2020a; Xu and Li, Reference Xu and Li2020; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tao, Zhang, Li, Ma, Yu, Sun, Li and Tao2021) and two recruited samples of overseas Chinese students (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Xiao, Luan, Kang, Yuan and Liu2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Kong and Nam2020b). A total of 23 studies adopted probability sampling to recruit subjects, while the remaining studies adopted convenience sampling. The sample sizes of included studies ranged between 84 and 746 217, with a median of 973. A vast majority of the studies collected data via online self-administered questionnaires, while seven collected data via paper−pencil self-administered questionnaires (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wen, Chen, Chen, Liu, Lu, Chen, Chen, Shen and Hu2020a, Reference Chen, Chen, Sun, Hu and Shen2020c, Reference Chen, Qi, Du, Chen and Ren2020d; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Wang, Wei, Mei and Chen2020; Liu, Reference Liu2020b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yuan and Luo2020b; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tao and Han2020). Among the included studies, the Nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was the most common instrument to assess the presence of depressive symptoms (n = 37), followed by Zung's Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) (n = 22), the depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (n = 8), the depression subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS-21) (n = 7) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D) (n = 7). The average and median reported prevalence rates of depressive symptoms were 27.3% and 25.8%, respectively. Other detailed characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study inclusion.

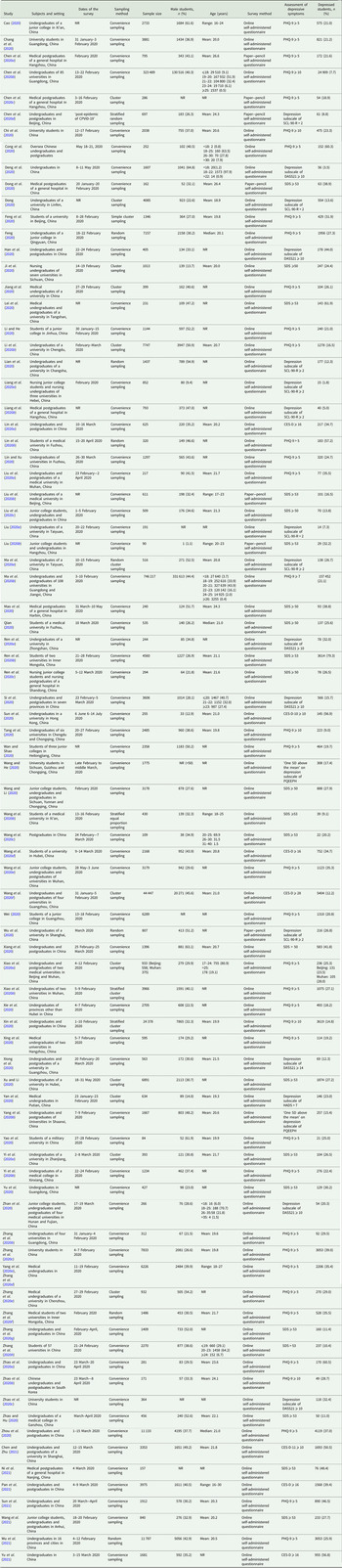

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

NR, not reported; s.d., standard deviation; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items; PQEEPH, Psychological Questionnaires for Emergent Events of Public Health; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SDS, Zung's Self-Depression Rating Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

RoB of included studies

In total, 31 studies had a RoB score of ‘0–3’, 42 had a RoB score of ‘4–6’ and 11 had a RoB score of ‘7–8’. No study was scored nine. The two most common methodological issues were inappropriate sample frame (n = 62) and problematic sampling method (n = 58) (online Supplementary Table 2).

Meta-analysis of prevalence of depressive symptoms

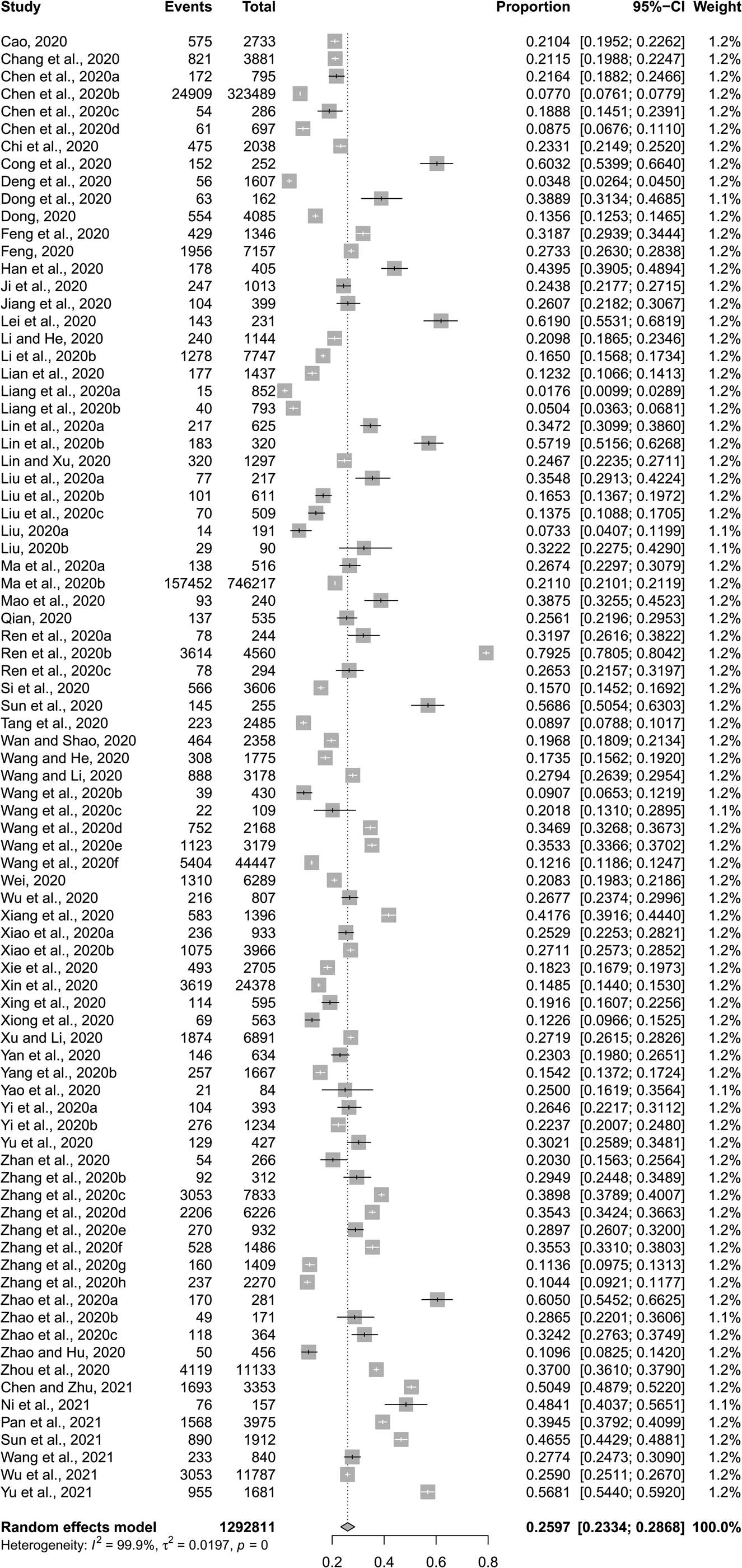

The pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students was 26.0% (%CI: 23.3–28.9%) (Fig. 2). Pooled prevalence rate of severe depressive symptoms was 1.69% (95%CI: 0.87–2.77%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Forest plot of prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 3. Forest plot of prevalence of severe depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

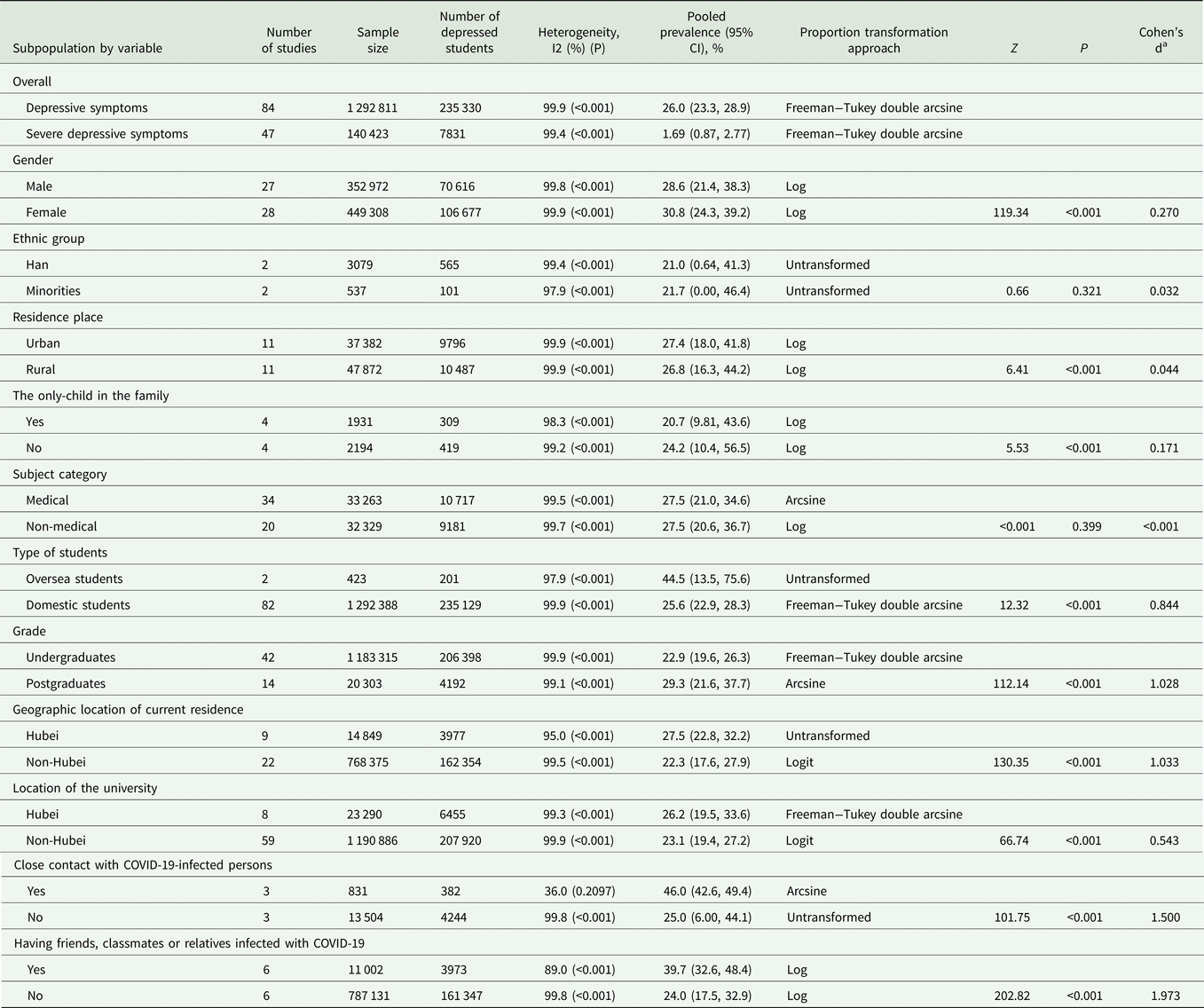

The combined prevalence rates of depressive symptoms were significantly higher in female than in male students (30.8% v. 28.6%, p < 0.001), in students with siblings than in only child students (24.2% v. 20.7%, p < 0.001), in overseas than in domestic students (44.5% v. 25.6%, p < 0.001), in postgraduates than in undergraduates (29.3% v. 22.9%, p < 0.001), in students living in Hubei than in those living in provinces other than Hubei (27.5% v. 22.3%, p < 0.001), in students from universities of Hubei than in those from universities of other provinces (26.2% v. 23.1%, p < 0.001), in students who were in close contact with COVID-19 than in those who had no history of COVID-19 contact (46.0% v. 25.0%, p < 0.001), and in students who had friends, classmates or relatives infected with COVID-19 than in those who did not (39.7% v. 24.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of meta-analyses of prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students

a Because sample sizes of different cohorts are very large, a statistically significant difference between two cohorts does not guarantee a clinical significant difference. To indicate the actual difference between two cohorts, Cohen's d was additionally calculated to assess the magnitude of the difference between the two rates, with 0.20–0.49, 0.50–0.79 and 0.80 and above being considered as small, medium and large actual differences, respectively. In the main text, we only reported the comparison results of different cohorts with Cohen's d values of approximately 0.20 or higher.

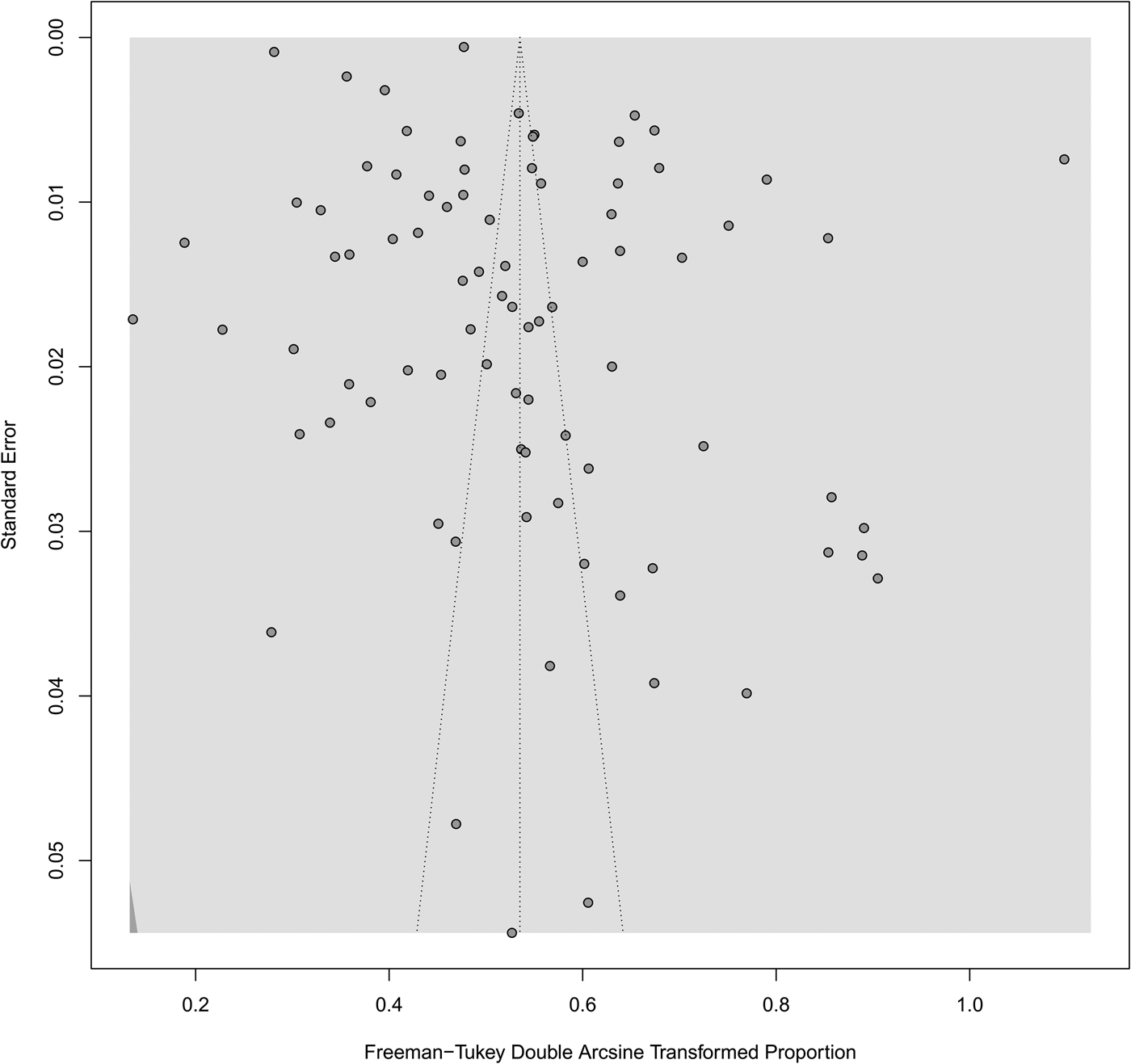

Publication bias among included studies

As shown in Fig. 4, the funnel plot was generally symmetric. The p value of the Begg's test was 0.169. No statistically significant publication bias was detected across the 84 included studies.

Fig. 4. Funnel plot of publication bias among the 84 included studies.

Source of heterogeneity

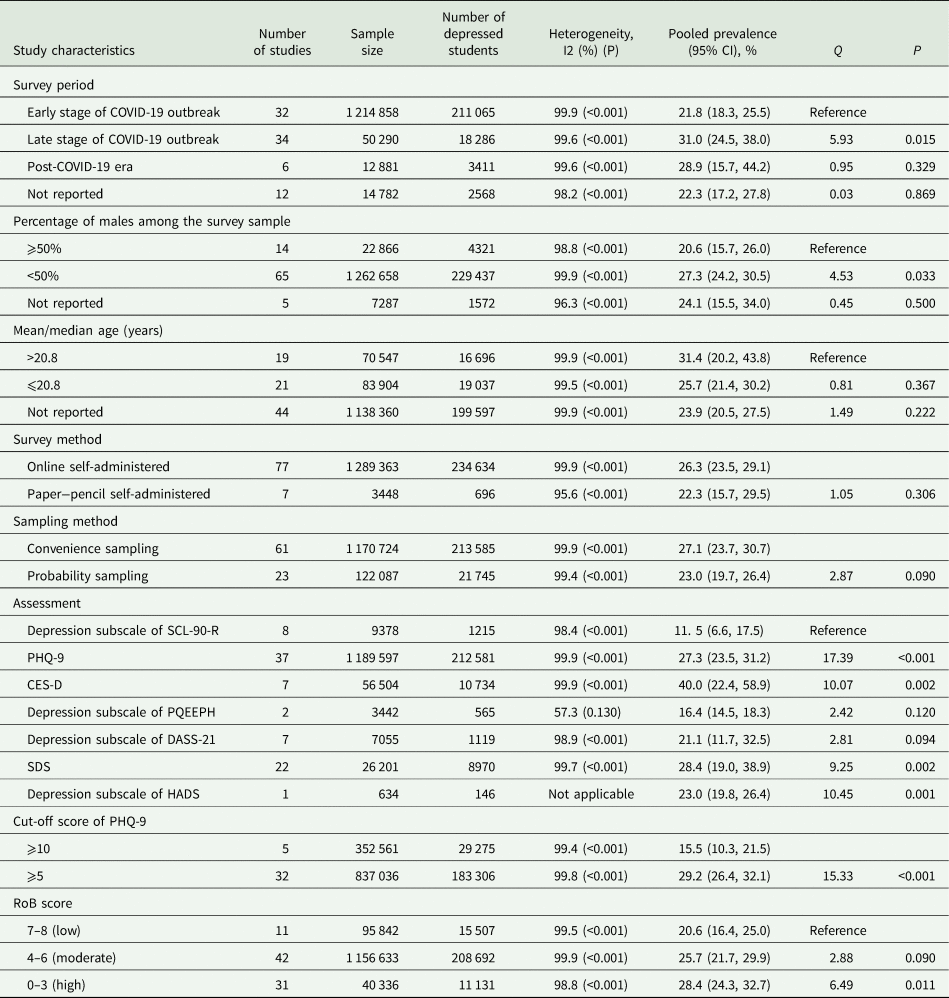

Five factors were identified as sources of heterogeneity across included studies (Table 3): survey period, % of male students among the total sample, scale of depressive symptoms, cutoff score of the scale of depressive symptoms and level of RoB. Specifically, significantly higher pooled prevalence rates of depressive symptoms were observed in studies conducted during the late stage of the COVID-19 outbreak than in those conducted during the early stage (31.0% v. 21.8%, p = 0.015), in studies with a percentage of males <50% than in those with a percentage of males ⩾50% (27.3% v. 20.6%, p = 0.033), in studies assessing depressive symptoms with CES-D than in those using SCL-90-R (40.0% v. 11.5%, p = 0.002), in studies defining the presence of depressive symptoms as ‘PHQ-9 ⩾ 5’ than in those defining it as ‘PHQ-9 ⩾ 10’ (29.2% v. 15.5%, p < 0.001), and in studies with a high RoB than in those with a low RoB (28.4% v. 20.6%, p = 0.011).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis of the source of heterogeneity of included studies

PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items; PQEEPH, Psychological Questionnaires for Emergent Events of Public Health; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SDS, Zung's Self-Depression Rating Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis summarised studies estimating the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We found an overall prevalence rate of 26.0% of depressive symptoms in Chinese university students and significantly higher rates in female students (v. males), in students with siblings (v. only children), in overseas students (v. domestic), in postgraduates (v. undergraduates), in students living within the COVID-19 epicentre (v. those living outside), in students from universities at the epicentre (v. those from universities of provinces other than Hubei), in close contacts of COVID-19-infected persons (v. those without a history of COVID-19 contact) and in students who had COVID-19-infected friends, classmates or relatives (v. those who did not). In addition, 1.69% of Chinese university students had severe depressive symptoms.

Compared to the 23.8% prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students during the non-COVID-19 era (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Xiao, Liu and Li2016), a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (26.0%) was found in Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the absolute difference between the two rates (2.2%) is not very large in magnitude. We argue that the result from this direct comparison should be considered with caution because of the significant heterogeneity in the methodologies of included studies. As shown in Table 3, the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms rose to 29.2% when included studies were restricted to those defining the presence of depressive symptoms as ‘PHQ-9 ⩾ 5’. Previously, empirical studies have reported that the prevalence rates of depressive symptoms in Chinese university students were 19.2% (PHQ-9 ⩾ 5), 7.8–12.6% (PHQ-9 ⩾ 10) and 26.9% (CES-D ⩾ 16) (He et al., Reference He, Chen, Liu, Fang and Li2014; Wu, Reference Wu2019; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Liang and Sheng2019; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhang, Yu, Sui and Wu2020b; Leung et al., Reference Leung, Mak, Leung, Chiang and Loke2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Zou, Gu, Meng, Gao and Shen2021), which are all lower than the corresponding figures in our study (29.2%, 15.5% and 40.0%, Table 3). Moreover, the 1.69% prevalence of severe depressive symptoms in our study was higher than that reported in two previous studies with samples of Chinese university students (0.5–0.9%) (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Yang, Liu, Tao, Zhang and Gao2019; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Chen, Liang and Sheng2019). These data suggest an elevated risk of depressive symptoms in Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to the abovementioned postponement of graduation, home quarantine and social disconnectedness due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the cooccurring ‘infodemic’ may also explain the elevated risk of depressive symptoms in university students. This is because smartphone and social media use are very popular among Chinese university students, and students are more likely to be exposed to negative information or even rumours from social media platforms such as short videos of overcrowded hospitals, physically and emotionally exhausted physicians and helpless infected patients. As a supporting case, in this pandemic, Chinese researchers have found the significant association between frequent social media exposure and depressive symptoms in the general population (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zheng, Jia, Chen, Mao, Chen, Wang, Fu and Dai2020a).

Cohort-specific prevalence of depressive symptoms

The higher risk of depressive symptoms in female than in male students during the COVID-19 pandemic is in line with the findings of previous studies with samples of general university students (Li et al., Reference Li, Wan and Zhao2018; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhang, Yu, Sui and Wu2020b; Ismail et al., Reference Ismail, Lee, Tanjung, Jelani, Latiff, Razak and Shauki2020). This phenomenon could be ascribed to the personality traits of females, such as higher levels of neuroticism/negative emotionality and conscientiousness, in comparison to males (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Kotov and Bufferd2011; Weisberg et al., Reference Weisberg, Deyoung and Hirsh2011). A meta-analysis of studies comparing the psychopathology between only children and children with siblings in China revealed the small mental health advantage experienced by only child university students in comparison to their peers with siblings, i.e. fewer psychiatric symptoms, including depressive symptoms (Falbo and Hooper, Reference Falbo and Hooper2015). It seems that this phenomenon also exists in university students affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e. significantly lower rate of depressive symptoms in only child students than in students with siblings, with a small magnitude of difference between the two groups (Cohen's d = 0.17) (Table 2).

One possible explanation for the higher risk of depressive symptoms in overseas than in domestic students is the status of ethnic minority groups in foreign countries (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Xiao and Tech2014). As migrants, overseas students per se have inadequate social support, and this situation worsens owing to the social distancing requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially increasing the risk of depressive symptoms (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Liu, Chan, Jin, Hu, Dai and Chiu2015). Due to the higher levels of academic stress in postgraduates than in undergraduates, it is generally believed that postgraduates are at higher risk for depressive symptoms than undergraduates in China (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang, Wang, Wei, Wang, Li and Wei2019). Similarly, a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in postgraduates than in undergraduates was observed in our study. According to our experiences with some university students from the crisis hotline services during the outbreak period, the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic achievement is greater in postgraduates than in undergraduates since undergraduates are able to continue their studies through online courses, but many postgraduates rely on university campus labs to continue their research. Because of the closure of campuses, postgraduates are more likely to be depressed.

Due to Hubei residents’ higher risk of infection and province-wide stringent mass quarantine measures, an elevated risk of depressive symptoms in students living in the epicentre relative to that in students living outside the epicentre is expected. Despite having left Hubei before the Spring Festival, students from universities in Hubei had been compulsorily isolated for medical observation in their hometowns and experienced a high level of discrimination and social exclusion due to their potential to spread the COVID-19 virus at the initial stage of the outbreak (He et al., Reference He, He, Zhou, Nie and He2020). Therefore, it is reasonable to find significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms in students from universities at the epicentre than in those from universities of provinces other than Hubei in our study.

Studies have reported the significant association of depressive symptoms with having relatives or acquaintances infected with COVID-19 in general populations of both China and Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Zhou, He, Li, Li, Chee, Xiang and Chiu2020). Consistent with these findings, the rate of depressive symptoms was significantly higher in university students with COVID-19-infected acquaintances or relatives, which may be attributed to these students’ high levels of concern about the health of the infected persons. Previous studies have found a greater level of fear of COVID-19 infection in persons who were suspected of having COVID-19, which was in turn associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms (Koçak et al., Reference Koçak, Koçak and Younis2021; Tsang et al., Reference Tsang, Avery and Duncan2021). For a similar reason, university students with a history of COVID-19 contact exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Findings from subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis revealed a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in studies with samples with fewer men, which is consistent with the female predominance phenomenon of depression (Albert, Reference Albert2015). However, what is counterintuitive is the higher risk of depressive symptoms in studies conducted late in the COVID-19 outbreak than that in studies conducted early in the COVID-19 outbreak in the subgroup analysis because the daily number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in China peaked during the early stage, and the outbreak was under control during the late stage. Similarly, a two-wave longitudinal study in China found increased severity of depressive symptoms in a cohort of the general population four weeks after the epidemic's peak relative to the initial COVID-19 outbreak (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Mcintyre, Choo, Tran, Ho, Sharma and Ho2020a). We speculate that during the early stage, people may have been shocked by the sudden outbreak, and they focused on safety and physical health. After the outbreak, the negative impacts of the pandemic, including economic loss and unemployment, gradually increased with time, leading people to feel depressed. Because of the problematic methodology of poorly designed studies, i.e. mental health surveys adopting convenience sampling are likely to recruit students having potential needs for mental health services, a statistically higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in studies with a high level of RoB was found in this study.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, none of the included studies were rated as completely low RoB. Subgroup analysis according to RoB level found a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in studies with a high level of RoB, so it is possible that the reported overall pooled estimate overestimates the true prevalence. Second, because several included studies used strict criteria to define the presence of depressive symptoms (i.e. PHQ-9 ⩾ 10), we may have underestimated the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Given the above two limitations, it is difficult to assess the magnitude and direction of bias in the prevalence estimate. Cautions are needed when generalising our findings. Third, even after stratifying the studies, high levels of heterogeneity were still kept within each strata of study in the subgroup analysis, so there remained other factors associated with the risk of depressive symptoms that were not identified. The heterogeneity of the results suggests that further rigorously designed studies using widely accepted assessments of depressive symptoms and representative samples of Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic are warranted to arrive at accurate estimates. Fourth, because of the small number of studies during the postoutbreak period, longitudinal data are needed to examine the trajectory of depressive symptoms in Chinese university students in the postpandemic era. Fifth, since the sample size of overseas students was relatively small (n = 423), the sample representativeness of overseas students may be limited in our study. Finally, patterns of utilisation of mental health services among depressed students are very important for mental health planning and policy-making in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the included studies provided little information on service use.

Implications and conclusions

In this study, over one out of every four Chinese university students had depressive symptoms, which suggests a high level of mental healthcare need in this population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression takes a high toll on individuals, families and societies, and, in particular, it is a major risk factor for attempted and completed suicide. Given the high prevalence of depressive symptoms, mental health services for this population amid the pandemic should include periodic evaluation of depressive symptoms to ensure early identification of students with severe depressive symptoms or high risk of suicide and psychiatric assessment and treatment when necessary. The higher prevalence rates of depressive symptoms revealed in several cohorts of Chinese university students (i.e. postgraduates, students living in the epicentre and COVID-19 contacts) indicate that cohort-specific prevention programmes, which are probably cost-effective, need to be designed.

China is a mental health services resource-poor country, so university managers and staff, including campus psychological counselors, should have a critical role in depression prevention; for example, they could provide expanded social support to students at risk, engage in follow-up care, mental health education and periodic screening of depressed students and promote social connectedness between students. Although the pandemic increases physical distances between staff and students, support services can be easily provided to students via smartphones.

In addition, the 28.9% prevalence of depressive symptoms during the postoutbreak era in this study (Table 3) and some small new COVID-19 outbreaks in recent months in China suggest the necessity of continuous mental health monitoring and services for Chinese university students during the postoutbreak era. Further rigorous research is also needed to understand the longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms of Chinese university students during the postoutbreak era.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000202

Data

All the data involved have been included in Tables and Figures of this paper, including supplementary files.

Financial support

The study was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.: 2018YFC1314303, PI: Xiang-Rong Zhang) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71774060, Bao-Liang Zhong, PI). The funding source had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.