Introduction

The 2018 election in Québec, Canada's second largest and only officially francophone province, was exceptional in several ways. It was the first fixed-date election in the province and was also marked by the landslide victory of the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), a relatively new centre-right party created ahead of the 2012 election. This election marked the first victory of a party other than the Parti Libéral du Québec (PLQ) or the Parti Québécois (PQ) since the creation of the latter in 1968. More importantly, for the first time, 47 per cent of the main parties’ candidates identified as female, well within the targeted “parity zone” (40 per cent to 60 per cent). In this article, we consider the media treatment of women in electoral politics. This case is interesting as it provides us with a rare opportunity to assess the coverage of female candidates in North America without having to control for the imbalance between the number of female and male candidates, meaning that journalists had nearly as many opportunities to discuss the campaigns of men and women. In fact, given that the heightened presence of female candidates for the first time in the province was heavily underlined by the media, one could expect that the novelty of the increased presence of female politicians would have been at the forefront of journalists’ minds throughout the campaign (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Trimble, Sampert and Gerrits2017). Given these exceptional circumstances, what can be said about the way female candidates are treated by the media when they are, for the first time, nearly as numerous as male candidates?

The goal of this article is twofold: (1) to determine if the coverage of female candidates is quantitatively different, and 2) to determine if the coverage of female candidates is substantively different. The article contributes to the literature in several ways. First, by using data gathered in a context of near parity, we circumvent important sampling dilemmas encountered in the literature on women and the media in politics. Studying differences in coverage often implies arbitrarily limiting the sample size to compensate for the underrepresentation of women. The remarkably high proportion of female candidates who ran in the 2018 Québec election allows us to take into consideration all of the articles published in 10 local news outlets during the campaign, eliminating any biases that could have resulted from the selection of a subset of articles targeting specific politicians. Second, it focuses on a case where the sheer number of female candidates was perceived as an historical achievement and a salient feature of the election. As Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Trimble, Sampert and Gerrits2017) note, novel candidates who are considered to be the first to achieve something generate greater media attention. In other words, this case presents opportunities that should be advantageous to women when it comes to media visibility. And yet despite those particularities, we find that women receive significantly less coverage than men. However, we find no variation in terms of the tone of that coverage.

The 2018 Québec general election campaign allows us to test two assumptions: that female candidacies are less mediatized (see, for example, Ross et al., Reference Ross, Evans, Harrison, Shears and Wadia2013; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Jacobs and Claes2015) and that this coverage is more negative (see Gidengil and Everitt, Reference Gidengil and Everitt2003). The hypothesis of the differentiated coverage of men and women by the media has recently come under fire, notably by Hayes and Lawless (Reference Hayes and Lawless2016), who assert that most female candidates in US House elections are treated the same by journalists.Footnote 1 The Québec case appears to be a great opportunity to reassert the balance of electoral coverage, as it may be expected that the exceptional number of female candidates during that year would have encouraged reporters to write about them more often or use positive vocabulary related to progress and equality.

In addition, we know very little about the coverage that local candidates receive during electoral campaigns in Canada, as the bulk of the existing research focuses on the coverage of party leaders at the national level and, to a lesser extent, at the provincial level (but see Everitt, Reference Everitt2003; Théberge-Guyon and Bourassa-Dansereau, Reference Théberge-Guyon and Bourassa-Dansereau2019).

Visibility, Female Candidates and the Media

Since most voters gather the political information they need from the media and never meet their local candidate or the leader of their favourite party (Lemarier-Saulnier, Reference Lemarier-Saulnier2018), the way certain groups of politicians are portrayed in the media is of democratic importance. The media not only show politicians but also frame the public's understanding of people and issues in politics (McCombs and Shaw, Reference McCombs and Shaw1972), meaning that they “shape the ‘informational environment’ in which citizens make choices, form opinions about policy and governance, and develop (or reinforce) ideological frameworks for interpreting information” (Trimble and Sampert, Reference Trimble and Sampert2004: 51). Campaigns, routinely staged around daily press conferences and televised debates, are portrayed in terms of a “horse race.” In this perspective, the campaign is framed as a race to the finish line (election day) by the media (Trimble and Sampert, Reference Trimble and Sampert2004). Reporting on these campaigns is influenced by several imperatives: the sheer cost of swift and continuous coverage (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2013); the need to keep the news attractive and interesting; and competition among different outlets, including social media. With over 500 candidates to cover during the 2018 elections in Québec (taking into account both major and marginal parties) and with increasing attention devoted to party leaders, local journalists were left with important choices to make. Which candidates would they concentrate their coverage on and what would they say about them?

Scholars around the world have looked at what factors could explain a given politician's presence or absence in the media. The media typically pay more attention to those involved in newsworthy events (Vos, Reference Vos2013), but Tresch (Reference Tresch2009) highlights three other explanations of visibility imbalance related to politicians’ personal characteristics: their activity, authority and privilege level. In other words, the media may devote time to politicians according to how involved they are in parliament and their community, but they may also take into account other factors, including political status (Aelst et al., Reference Aelst, Sehata and Van Dalen2010). Researchers have also raised gender as a possible source of inequality, in terms of media exposure (Vos, Reference Vos2013). The choices made by journalists are not without political consequences, as media visibility has been associated with a greater vote likelihood (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Vliegenthart, De Vreese and Albæk2010).

According to Sreberny-Mohammadi and Ross (Reference Sreberny-Mohammadi and Ross1996), the political representation of women rests on two principles: allowing them to speak in the political arena, and actually showing them in the media. Since the 1980s, researchers have called attention to a tendency to devote less media attention to female candidates (Gingras, Reference Gingras and Gingras1995; Stanley, Reference Stanley2012), which leads to what Tuchman (Reference Tuchman1978) calls women's “symbolic annihilation” from the public sphere. The relative absence of female candidates and politicians in the news has notably been highlighted in Europe (Lühiste and Banducci, Reference Lühiste and Banducci2016; Vos, Reference Vos2013). Nevertheless, some authors have raised doubts about the prevalence of gendered media erasure (Smith, Reference Smith1997; Semetko and Boomgaarden, Reference Semetko and Boomgaarden2007). In the case of Canada, Goodyear-Grant (Reference Goodyear-Grant2013) finds no significant difference during the 2000 and 2006 Canadian federal elections, meaning that the candidacies of women were as visible as men's in the news. However, looking at provincial elections in the Maritimes, Everitt (Reference Everitt2003) documents some evidence of a quantitative bias in the news coverage in certain provinces. Several reasons could explain these variations in the number of articles published about male and female candidates. Perhaps one of those most frequently raised is that women in Canada are more likely than men to serve as “sacrificial lambs” by running in districts where their party has virtually no chance of winning (Thomas and Bodet, Reference Thomas and Bodet2013). It could be expected that candidates not in a competitive position would attract less media attention (see Kahn Reference Kahn1992; Smith, Reference Smith1997; Jalalzai, Reference Jalalzai2006) or that the attention received would be centred on their electoral viability (Everitt, Reference Everitt2003). This is true not only in Canada but also on a global scale, as Belt et al. (Reference Belt, Just and Crigler2012) note that US media are also particularly interested in candidates they deem viable. In Canada, Trimble (Reference Trimble2007) notably assessed the influence of the competitiveness of female candidates on their media visibility in the 1976, 1993 and 2004 Conservative party leadership races. She noted that less competitive female candidates typically received more coverage than their male counterparts. Moreover, some research looking at federal leadership races between 1975 and 2012 (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Trimble, Sampert and Gerrits2017) found that competitiveness, as well as novelty, can have a greater impact than a candidate's gender on media visibility.

Two trends are clear in the Canadian literature on the treatment of women by the media during elections. First, researchers tend to focus on federal politics, while provincial elections have not received nearly as much attention (see, for example, Everitt, Reference Everitt2003). Second, most studies—with notable exceptions, including Goodyear-Grant (Reference Goodyear-Grant2013) and Everitt (Reference Everitt2003)—look at party leaders or at a few high-profile politicians. Therefore, much remains to be understood about the coverage of local female candidacies.

On issues relating to the tone used by journalists, the evidence from the international literature is mixed. While certain researchers report little evidence of bias (for example, Bystrom et al., Reference Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart2001), others report that journalists are more likely to feature either male (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Peake and Boulton2010) or female (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Conley, Szymczynska and Thompson2002) politicians under a more positive light. A recent meta-analysis concludes “that there is no clear indication of a gender bias in the tone of the coverage of politicians,” highlighting the disparities in the results of the different studies on this topic (Van der Pas and Aaldering, Reference Van der Pas and Aaldering2020); it is, however, important to note that the 27 studies included in this part of their meta-analysis use a broader notion of “tone” than we do in this article. What they label as “toned reporting” is not entirely clear and regroups studies focusing, for example, on gendered stereotypes, physical appearance and blatant sexism. This meta-analysis casts a wide net, regrouping qualitative studies manually identifying gender stereotypes in the news coverage of a single woman politician, as well as studies built on the longitudinal quantitative analysis of a quantified measure of tone for hundreds of politicians. It should also be pointed out that a number of these studies do not explicitly discuss tone but were rather labelled as such by the authors of the meta-analysis. Given those considerations, it is not entirely surprising that the authors report that “the data do not suggest that the country or region, type or level of the political office, type of medium, or time moderates the relationship [between gender and tone].” In contrast with most of those studies, we use a relatively narrow and quantitative operationalization focusing on affectively loaded words, as discussed in our methods section.

In the end, one of the main problems encountered by researchers in Canada, as elsewhere, is that women represent the minority of candidates in the majority of electoral scenarios. We therefore know very little about the media treatment of female candidates when journalists are given roughly as many opportunities to discuss them as men. The exhaustive review presented in this article of the 2018 Québec election's press coverage, including all articles published during the campaign from all major newspapers in the province, therefore sheds a different light on what we know about the way journalists write about female candidates.

Research Design and Hypotheses

Case selection

We begin with a justification for the case selection through an overview of the political context surrounding the 2018 election. Two of its characteristics are of interest: not only was there a high proportion of female candidates but these numbers were also considered unusual country-wide and led to specific media coverage. Overall, parity was portrayed as a novelty in the province. While less than a third of candidates (30 per cent) were women four years earlier, their numbers grew to nearly 50 per cent in 2018. This progress in such a short period of time was covered at length in the media. What sparked this increase remains unclear, however, as no gender quotas were enforced. Even before the four main partiesFootnote 2—Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), Parti libéral du Québec (PLQ), Québec solidaire (QS) and Parti Québécois PQ)—were done selecting candidates, the press was already discussing, and even celebrating, what appeared to be the greatly increased presence of women (Bourgault-Côté, Reference Bourgault-Côté2018). In the end, 41.6 per cent of the members of the National Assembly (MNAs) elected that year were women (Canadian Press, Reference Press2018). As a comparison, in 2015, following the last federal elections in Canada, 26 per cent of members of parliament (MPs) identified as women, the most in the country's history. Québec became, in 2018, the Canadian province to have elected the greatest number of women, surpassing neighbouring Ontario. This achievement was emphasized in national media,Footnote 3 and the campaign was deemed historical. Québec therefore offers an opportunity to test for imbalance in coverage in circumstances where one could expect female candidates to be at least as frequently discussed as men—if not more, given the interest sparked by their unusual numbers.

Four parties competed in the 2018 election. The PLQ was led by Philippe Couillard (man), who was premier of the province prior to the election (from April 2014 to October 2018); Couillard, a neurosurgeon, became the leader of the centre-right political party in 2013. Following the 2018 elections, the PLQ lost government and became the official opposition. Half of its 32 seats were held by women.Footnote 4

What mostly sets the PLQ apart from the PQ is its stance regarding Québec's independence. While the PLQ favours Canadian federalism, the PQ was the main secessionist party at the National Assembly prior to 2018. The PQ is commonly considered a centre-left party; it was led, in 2018, by Jean-François Lisée (man), and Véronique Hivon (woman) was considered the party's co-leader. She would have become vice-premier had the PQ won the 2018 election. Instead, her party suffered a monumental defeat and lost its status as the official opposition. Around 30 per cent of the PQ's MNAs were women.

Founded in 2006, QS does not have a leader per se, but two “co-spokespeople”: a man and a woman. Before 2018, QS was considered a marginal leftist, social-democratic party. However, QS managed to elect 10 MNAs, including co-spokesperson Manon Massé (woman) and Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois (man), in October 2018. The MNAs for QS thus became as numerous as those for the PQs. Half of the MNAs for the QS were women.

Lastly, the 2018 elections were won by the CAQ (“Coalition for Québec's Future”). The CAQ, a centre-right party, was created in 2011 by former PQ minister François Legault (man) and Charles Sirois. Legault is still, as of the writing of this article, the CAQ's leader and premier of Québec as of 2018. Despite Legault's past association with the PQ, the CAQ does not support Québec's independence. In 2018, the number of CAQ's MNAs increased from 22 to 75. Twenty-two of its elected candidates were women.

The articles

Our dataset is composed of every news article published in 10 different outlets between August 23 and October 1, 2018. Data collection involved scraping news outlet RSS feeds.Footnote 5 The complete dataset is composed of 18,797 news articles from the following sources: Radio-Canada, Le Droit, La Presse, Le Nouvelliste, Le Devoir, La Tribune, Le Journal de Montréal, Le Quotidien, La Voix de l'Est and Le Soleil. Radio-Canada is a publicly funded outlet available in both official languages.Footnote 6 The French-language edition is considered here. Le Droit is an Ottawa-Gatineau based newspaper, which also covers the Gatineau area of Québec. La Presse and Le Devoir are two privately owned Montreal-based newspapers aimed at the entirety of the province. Other dailies included are devoted to regional news: Le Nouvelliste is based in Trois-Rivières, La Tribune in Sherbrooke, Le Journal de Montréal in Montreal (but it is distributed widely and has the largest circulation), Le Quotidien in Saguenay, La Voix de l'Est in Granby, and Le Soleil in Québec City. Table 1 presents the ownership, region and readership for our nine newspapers. To be noted is that readership figures account for both online (website) and offline (print) news consumption as detailed by the Centre d’études sur les médias (CEM), the source for these data.Footnote 7

Table 1 Ownership, Region and Readership of Quebec's Nine Main Newspapers

Obviously, not all these articles were related to the election and the dataset required considerable cleaning. In order to identify and keep only the coverage of candidates we identified the sentences mentioning them. This was done for every candidate of the four main parties for a total of 500 candidates (four for each of the 125 ridings). First, we had to check that the names of the candidates we obtained from Élections Québec (the independent institution in charge of the elections) were in line with journalist coverage. Three typical problems were encountered: the first was the inconsistent use of hyphens for double-barrelled surnames and given names, the second was the inconsistent use of initials and the third was the inconsistent use of accents in names. A good example to illustrate these issues is the candidate Carlos J. Leitão: we found 37 mentions using “Carlos Leitão”; 81 using “Carlos Leitao”; and none when using his initial. In order to circumvent these issues, we opted to remove all accents and hyphens from our list of names and the corpus for the matching process, and we kept or removed the initials on a case-by-case basis. In some cases, the initial had to be replaced by the complete name in order to get matches, such as for Samuelle Ducrocq-Henry, who was registered as “Samuelle D.-Henry” with Élections Québec. This process left us with a total of 21,267 sentences.Footnote 8

The volume

One of our two dependent variables of interest is the volume of the coverage received by each candidate. This was operationalized as the number of sentences mentioning each of our 500 candidates. It constitutes a “count” variable and will be treated as such in the analysis.

While an important part of the comparative literature shows that women candidates are often less likely to be featured in the news (see Ross et al., Reference Ross, Evans, Harrison, Shears and Wadia2013, in Great Britain; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Jacobs and Claes2015, in Belgium), some researchers, notably in the United States, have questioned the assumption of a gender imbalance in press coverage that would penalize female candidates (Banwart et al., Reference Banwart, Bystrom and Robertson2003; Bystrom et al., Reference Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart2001; Jalalzai, Reference Jalalzai2006). In Québec's context, we could not find similar assessments of women candidates’ coverage. We therefore test for a quantitative imbalance in coverage through the following hypothesis:

H1: Women candidates will receive less news coverage than male candidates.

The tone

Our second dependent variable of interest is the tone of the news coverage every candidate received. To test for this, we employed the French version of the Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (LSD), originally created by Young and Soroka (Reference Young and Soroka2012) and translated/adapted into French (FrLSD) by Duval and Pétry (Reference Duval and Pétry2016). The FrLSD is a lexicon created to measure the tone of the news coverage. It is composed of over 4,000 words, each assigned either a negative or a positive tone. Using the R package quanteda (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018), we ran this dictionary on all our sentences to obtain the number of positive and negative words per candidate. The actual tone variable stands for the proportion of positive words minus the proportion of negative words: [(# of positive words − # of negative words) / total number of words in the article]. To illustrate this, let's consider the following (translated) sentence from our corpus: “Manon Gauthier, a candidate in Maurice-Richard, in Montreal, had been found guilty of driving under the influence.”Footnote 9 The bolded words “guilty” and “influence” (“facultés affaiblies” in French, which would literally translate to “weakened capacities”) are negative in our sample, whereas the other words are in neither the positive nor negative categories. This would give us a tone score of −0.12 [0 positive words − 2 negative words / 17 total words] for this particular sentence for this candidate. The FrLSD is a precise way to measure the tone of news articles; when compared against the other existing French content-analytic dictionary, it produced results that were closer to those of human coders (Duval and Pétry, Reference Duval and Pétry2016).

Lemarier-Saulnier's (Reference Lemarier-Saulnier2018) study of the media coverage of party leaders during the 2014 Québec election highlights the prevalence of gendered framing by news outlets in this province, but little is known about the tone used by Québec journalists when discussing female politicians. There is reason in the literature to hypothesize that this tone could be substantially different from the one used to refer to male politicians. The distance between feminine stereotypes and what is typically expected of politicians has notably been raised to explain this possible disparity, but there is no consensus on the matter. Overall, empirical findings appear mixed, as both positive and negative tones have been observed when referring to women in politics (Van der Pas and Aaldering, Reference Van der Pas and Aaldering2020). We therefore hypothesize:

H2: The coverage of women candidates will significantly differ from male candidates.

Our analysis will also include a number of independent variables. Perhaps the most important one for our purpose is the Gender variable, which is largely self-explanatory. We also include the following control variables: Party (factor with four levels, where the CAQ is the comparison level); Leader (which identifies our four party leaders: François Legault, Philippe Couillard, Manon MasséFootnote 10 and Jean-François Lisée, all of whom received significantly more coverage); and Incumbents, a dummy variable identifying the incumbent candidates to account for a possible incumbent advantage (see Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Nicolas, de Vreese and Albæk2011). Similarly, with an included dummy variable identifying outgoing ministers, we also have a dummy variable accounting for Montreal and Québec City Ridings and, lastly, a Competitive Riding dummy variable identifying ridings where the difference between the elected candidate and the second-place finisher was less than 15 per cent of the vote (this is a common measure in the Canadian context—see, for example, Thomas and Bodet, Reference Thomas and Bodet2013; Young, Reference Young, Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006; Paperny and Perreaux, Reference Paperny and Perreaux2011).Footnote 11 Overall, 44 of the 125 ridings were competitive by this metric. Lastly, we also added a Candidate Competitiveness variable that ranks each candidate according to where they placed in the competition (first, second, and so on), thereby allowing a robust test of electoral viability, the idea being that the more electorally viable candidates are more newsworthy (see Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Trimble, Sampert and Gerrits2017).Footnote 12

Results

As mentioned above, there are 21,267 mentions of candidates in our dataset. The magnitude of the coverage varies considerably by news outlets. A full 2,807 mentions are from Radio-Canada; 1,836 are from |Le Droit; 1,619 from |La Presse; 2,052 from |Le Nouvelliste; 1,998 from |Le Devoir; 2,142 from La Tribune; 3,075 from Le |Journal de Montréal; 1,939 from |Le Quotidien; 1,941 from La Voix de l'Est; and 1,857 are from Le Soleil. Of those mentions, 4,844 covered female candidates and 16,423 were centred on male candidates. Considering that 235 individuals identify as women in our sample and 265 as men, the difference is quite stark.

However, this discrepancy might be slightly misleading given that 12,241 of those mentions were party leaders—one woman and three men—which considerably skews the figures we just presented. As mentioned, leaders are by far more frequently discussed in the media than local candidates (Tresch, Reference Tresch2009). François Legault, the party leader of the CAQ, was mentioned 4,248 times; Philippe Couillard, the party leader of the PLQ, was mentioned 3,649 times; Manon Massé, the co-spokesperson of QS, was mentioned 1,412 times; and Jean-François Lisée, the party leader of the PQ, was mentioned 2,932 times. Given that the PQ and QS fared very similarly in this election, there is an argument to be made that there is an imbalance, quite possibly gendered, here.

Excluding party leaders, we are left with 9,026 mentions. Of those, 3,432 were of the 234 women candidates in our sample, for an average of 14.7 mentions per female candidates, and 5,594 were of the 262 male candidates, for an average of 21.4 mentions per male candidates. Again, there appears to be a marked difference, although it is not quite statistically significant (p = .057).Footnote 13

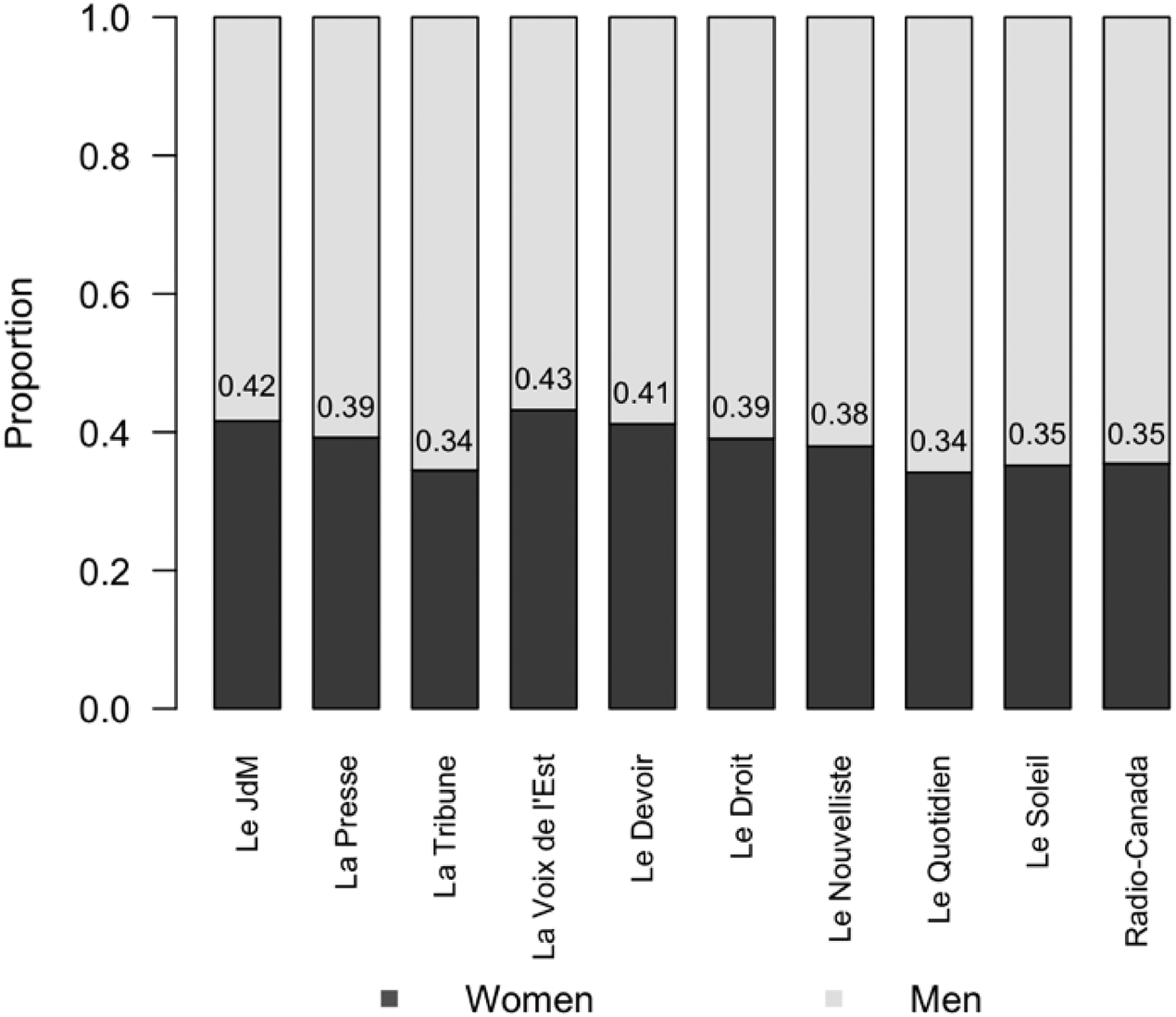

Figure 1 illustrates that this contrast is found in all of the news outlets in our sample. Women candidates, who represent 47 per cent of our sample (once we exclude party leaders), received only between 34.1 per cent (Le Quotidien) and 43.2 per cent (La Voix de l'Est) of the measured coverage, with a mean value of 35.3 per cent. Furthermore, we do not observe any difference worth mentioning between provincial newspapers and local ones.

Figure 1 Proportion of Mentions of Candidates by Gender and News Outlet

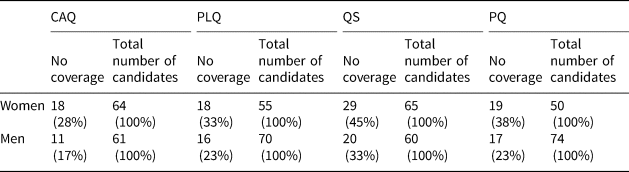

However, this does not tell the full story. As hinted in the previous section, many candidates are simply not mentioned in our corpus. Table 2 shows the breakdown of this phenomenon by parties. Of our 500 candidates, 84 women (36 per cent of all the women in the sample) and 64 men (25 per cent of all the men in the sample) were never mentioned. Again, there appears to be a gendered imbalance in who gets covered. Of the 29 candidates that received no coverage for the CAQ, 18 were women and 11 were men. For the PLQ, we found that 18 female and 16 male candidates received no coverage. For QS, we found that 29 female and 20 male candidates received no coverage. And for the PQ, we found that 19 women and 17 men candidates received no coverage. The results are similar across the board, with women receiving less coverage than men. This appears to be especially the case for the female candidates of QS, with a difference of 12 percentage points between the proportion of uncovered women and men, and for the female candidates of the PQ, with a difference of 15 percentage points between the proportion of uncovered women and men. It's also worth mentioning that regardless of gender, QS candidates appear less likely to receive news coverage. This is quite apparent when we compare these figures with the PQ ones, who as mentioned already, fared very similarly in this election.

Table 2 Absence of Coverage of Candidates by Party

These descriptive results are summarized in Figure 2. To ease visualization, we created five categories in order to illustrate the various numbers reported in the previous paragraphs. In short, this figure presents the number of candidates who received “no coverage,” “1 to 5 mentions,” “6 to 15 mentions,” “16 to 35 mentions” and “more than 35 mentions,” and it does so for all candidates (left side of figure) and grouped by gender (right side of figure). Figure 2 makes it particularly clear that women are much less likely to be covered by the media than male candidates across the board.

Figure 2 Frequency of Mentions of Candidates

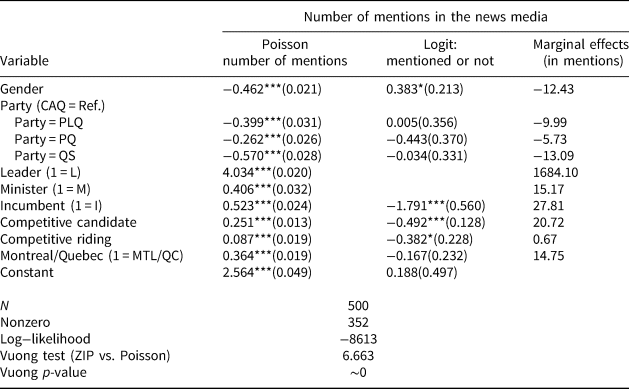

Moving on from our descriptive results, Table 3 presents a zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) count model with the number of mentions (sentences in our corpus) as the dependent variable. The first column presents the Poisson portion of the model (that is, the number of mentions each candidate is likely to receive, conditional on our variables) and the second column presents the logit portion of the model (that is, the effect of our variables on the likelihood that a candidate receives any coverage). We present the combined marginal effects in the third column for ease of interpretation.

Table 3 Zero-Inflated Poisson Count Model Estimates of the Number of Mentions Each Candidate Received

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

The results shown in Table 3 support our first hypothesis: that women candidates will receive less news coverage. Keeping everything else constant, women are mentioned 12 times fewer than men, even though female candidates were nearly as numerous as male candidates in 2018. Our results do indicate that there was a gender bias in the coverage of this Québec provincial election, which is particularly surprising and significant given the increased presence of women among candidates. As mentioned earlier, the exceptional number of female candidacies could have encouraged journalists to pay more attention to them. Our results show that this did not happen. In spite of exceptional circumstances, media granted less attention to female candidacies.

Looking at the marginal effects of our other variables, we also see that the CAQ seemed to have a certain advantage when it came to being covered in the news, as all three other parties were not as frequently mentioned on average. Party leaders, incumbents and ministers receive much more coverage than other candidates. This is not surprising given the gradual “concentration of power” around leaders in many democracies (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2007), a phenomenon described as the “presidentialisation” of politics. Party leaders and their personalities matter a lot in Canada (for work on party leaders in the Canadian context, see Bittner, Reference Bittner2011, Reference Bittner2018). Whether the riding was considered competitive or not had virtually no effect on the coverage received by candidates. This surprising result probably warrants further investigation, which is outside the scope of this article. However, the competitiveness of the candidate did have a substantial effect; the elected candidate received on average 21 more mentions than the candidate finishing last (among the four parties considered).

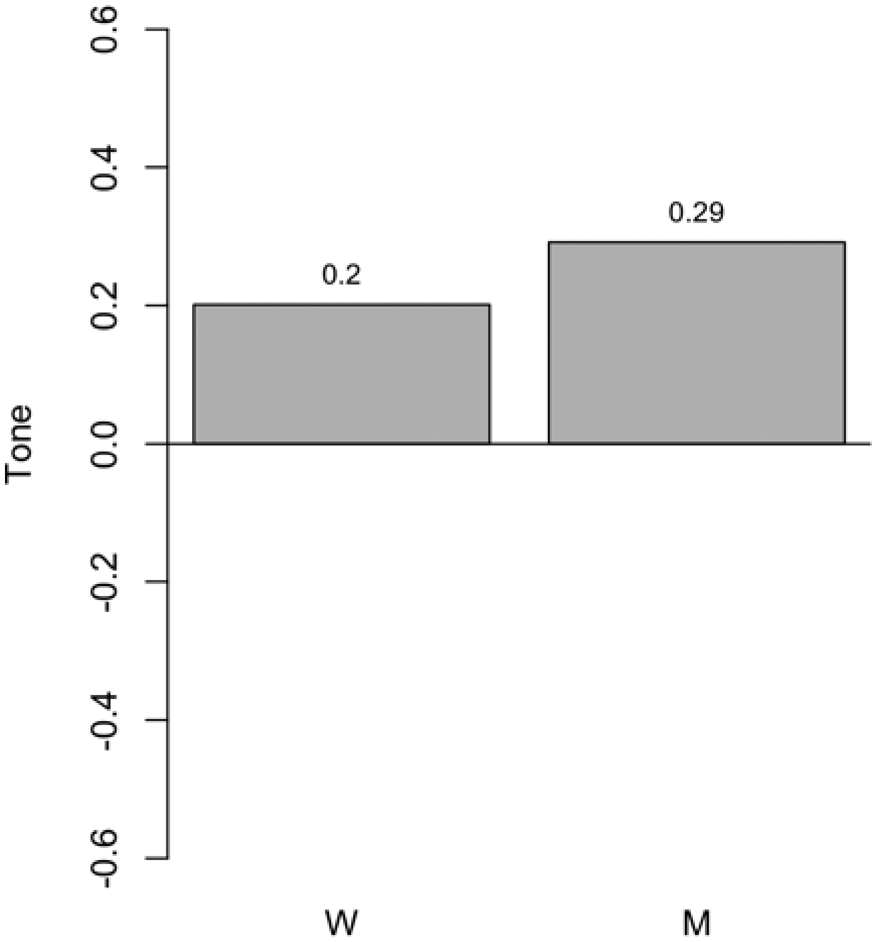

Moving on to the tone of the coverage received by candidates, Figure 3 displays the mean for the tone scoresFootnote 14 of our 352 candidates that received news coverage. Women candidates (W) in our sample have a tone mean of 0.20; comparatively, the men (M) in our sample have a tone mean of 0.29. While the tone of the news coverage received by women candidates is lower, a test of means comparison reveals this is not statistically significant,Footnote 15 which is corroborated by the ordinary least squares (OLS) model that can be found in Appendix A. There appears to be no significant gender-based aggregate-level tone difference in the coverage received by the candidates during the 2018 Québec electoral campaign.

Figure 3 Average Media Tone by Gender

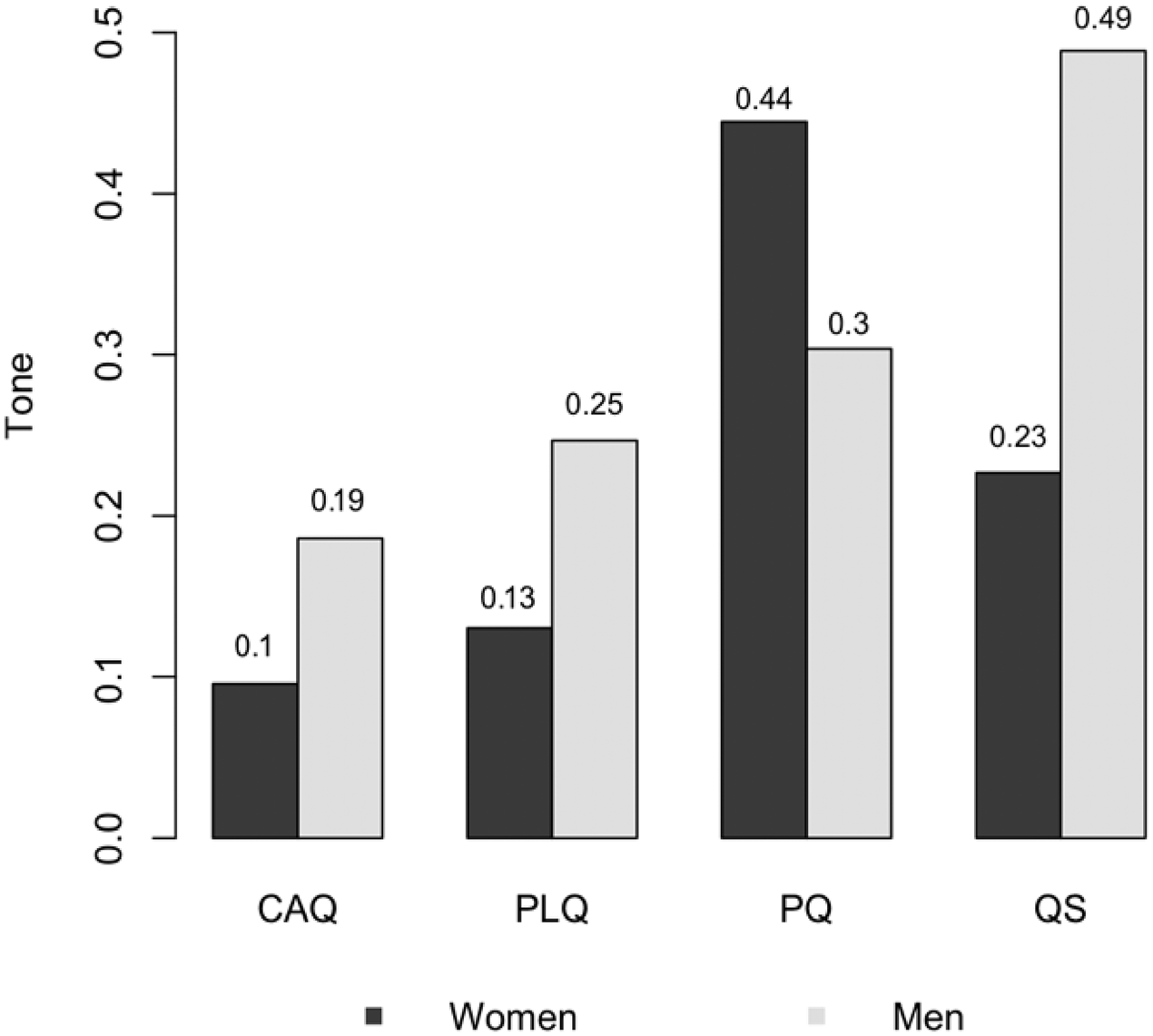

Looking at the tone of the news coverage by the party and by gender, the picture is slightly different. Figure 4 presents these results. For three of the four parties in our sample, women candidates received a more negative tone, somewhat surprisingly, considering that in our results so far, the news coverage of the women candidates for the PQ appears more positive than the coverage received by men candidates for the same party. Unsurprisingly, given our OLS model of the tone of the news coverage found in Appendix A and our aggregate-level test presented above, none of these differences in means are statistically significant.Footnote 16

Figure 4 Average Media Tone by Party and Gender

Discussion and Conclusion

This article uncovers a gendered bias in the news coverage of candidates despite the parity observed during the 2018 Québec general election. Political observers and journalists alike applauded parties during this election because 47 per cent of the candidates identified as women. While this represents a non-negligible improvement, we show that these women only received 38 per cent of news coverage, which highlights that much remains to be done when it comes to women's representation in news media. No consensus has been reached in the comparative literature regarding coverage inequality. Some scholars have found that women candidates are less likely to be featured in the news (for example, Ross et al., Reference Ross, Evans, Harrison, Shears and Wadia2013; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Jacobs and Claes2015; Kahn and Goldenberg, Reference Kahn and Goldenberg1991; Heldman et al., Reference Heldman, Carroll and Olson2005), while others have found no gendered imbalance in press coverage (Banwart et al., Reference Banwart, Bystrom and Robertson2003; Bystrom et al., Reference Bystrom, Robertson and Banwart2001; Jalalzai, Reference Jalalzai2006). Our results sit firmly alongside the first group, as we find a sizable gendered gap in the coverage. In other words, even though Québec media were highlighting what was seen as the improvement of gender equality during the campaign, journalists nonetheless reverted to old habits by devoting greater attention to male candidates. While it is argued that the increased presence of women in politics could ultimately result in a more equal press coverage (Fernéndez, Reference Fernéndez2015), our results show that even when a “parity zone” is reached, this may not be the case.

Somewhat surprisingly, we did not find any significant differences when it comes to the tone of the coverage female candidates receive. However, since we used sentiment dictionaries and relied on an automated process, we must remain cautious regarding our claims related to the tone of the coverage. While this result could also be a sample size issue, what is more likely is that our measure of tone cannot account for the dynamics at play in the coverage of candidates. More precisely, it is entirely possible that the lexicon we used can only capture “outright negativity” and misses more subdued sexism, such as comments on a woman's appearance and personal life or on gender roles and “feminine” traits, and so on. While this measure is an important limit to the scope of our analysis, it also represents an avenue for future research, as creating a French lexicon capturing those gendered comments seems entirely feasible. Several researchers, in Canada and elsewhere, have already raised the likelihood of a gendered difference reflected in the content of news articles (see, for example, Goodyear-Grant, Reference Goodyear-Grant2013; Gidengil and Everitt, Reference Gidengil and Everitt2003; Lemarier-Saulnier, Reference Lemarier-Saulnier2018).

Another technical point worth noting is that we did not consider how early in the news articles each of the candidates were mentioned. This issue could be worth investigating in future research, given that we know news stories are inverted pyramids, with the most valuable content placed first or featured prominently in the headline or a photo and also given that we also know that many people stop reading after the title or the lead paragraph. Arguably, these mentions could be more valuable to candidates.

Another limit to our study is that we focus on only one type of media. While our dataset does a good job capturing the vast majority of print newspapers and online outlets at play in the Québec media sphere, we completely omit television, radio and social media. Lemarier-Saulnier (Reference Lemarier-Saulnier2018) showed, however, that TVA22h, the nightly news report aired on the most watched channel in Québec, was particularly susceptible to resorting to a gendered framing of female party leader Pauline Marois in 2014. Therefore, we feel that if we analyzed radio and television excerpts, as well as social media posts, the gendered differences could be even more important.

Lastly, gender is only one of the key variables social scientists need to study when it comes to analyzing news media coverage. Like much of the literature focusing on representation in news media, we ought to go beyond the gender gap. Put otherwise, further research should also incorporate a focus on other historically marginalized groups, such as individuals associated with ethno-cultural minorities. In this regard, the adoption of an intersectional lens taking into account the interactions of gender-based and race-based media frames appears fruitful. This will be our goal as we expand this research agenda. Nonetheless, this article shows that parity is not the key to solving coverage bias in the media, as the typical framing of politics still has more weight than recent progress in terms of representation.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marc Bodet and Olivier Banville for allowing us to use these data. We are also grateful for the valuable comments we received from the participants of the 2019 CPSA Canadian Political Communications panel and from the three anonymous reviewers. This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (ref #430-2020-01165).