The United Nations Human Settlements Programme estimates that about one-third of the urban population in Latin America lived in informal tenure situations around the turn of the millennium (UN-Habitat 2003:14). In spite of great variation between tenure situations, the default view, implicit in government policies, development initiatives (e.g., rule of law and land titling programs), and theoretical accounts, is premised on a dualistic logic that assumes tenure to reside either entirely inside or completely outside the law. However, while dominant legal doctrine may still regard the city as no more than a bounded area comprising demarcated plots of land in individual ownership, as Reference Fernandes, Varley, Fernandes and VarleyFernandes and Varley (1998:6) note, in practice, one frequently encounters a variety and flux in tenure situations that renders the border between the formal and the informal more blurry than clear (Reference AzuelaAzuela 1987; Reference BentonBenton 1994; Reference Durand-LasserveDurand-Lasserve 2006). Settlements, and even dwellings within settlements, have been found capable of shifting tenure categories, and subtle differences between them, which may be invisible to outsiders, can be critical to those living in them (Reference PaynePayne 2001:418). Therefore, the inability of perspectives relying on dichotomous legal-illegal notions to consider the “informal” parts of the city makes them ill equipped for a constructive legal analysis of urban development and an understanding of the growth of informality in Latin America and elsewhere in the developing world. Examining mere compliance or deviance from the letter of the law says little about these dynamics and is likely to lead to misinformed policymaking.

An example of the way this becomes manifest regards attempts to establish security of tenure. A centerpiece of current development policy, and also a fundamental element of the right to housing, tenure security is widely assumed to encourage investment in housing improvement and lead to capital gains for dwellers. A consequence of the dichotomous view is that tenure situations designated as illegal are also assumed to be insecure by default, while those that have been legalized are thought to be secure by definition (see Reference Van GelderVan Gelder 2009). These assumptions stand at odds with the fact that informal neighborhoods in cities throughout the developing world have been found to enjoy reasonable degrees of (de facto) security of tenure (e.g., Reference Durand-Lasserve and SelodDurand-Lasserve & Selod 2007; Reference GilbertGilbert 2002; Reference VarleyVarley 1987), whereas residents in neighborhoods that have been legalized may (still) face threats of eviction as a consequence of market pressures (Reference AngelAngel 1983; Reference DoebeleDoebele 1987; Reference Fernandes, Durand-Lasserve and RoystonFernandes 2002; Reference Von Benda-BeckmannVon Benda-Beckmann 2003).

The limitations of the dichotomous perspective have been recognized in both sociolegal theory and development research, and both strands of academic discipline have offered their proper alternative views to deal with the issue. In the case of the sociolegal tradition, this has taken the form of legal pluralist approaches to informality (e.g., Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos 1977; Reference RazzazRazzaz 1994). Development research has promoted the treatment of land tenure as a continuum (e.g., Reference PaynePayne 2001; UN-Habitat 2003). Below, I first discuss both alternative views before arguing that they, diverse as they at first sight may appear, can in fact be integrated into a (more) comprehensive framework. The remainder of the article is devoted to an empirical demonstration of how the framework plays out in the case of land invasions in Buenos Aires.

Alternatives to the Dichotomy

The Legal Continuum Argument

According to the legal continuum argument, which has been gaining prominence in development discourse, the dichotomous perspective falls short because settlements and tenure situations within settlements in Third World cities in practice vary in the degree to which they are legal, rather than being either illegal or legal. Land tenure, it is argued, is more properly conceived of as a continuum with different levels of legality, in which some forms of tenure also tend to be more accepted and tolerated than others (Reference Fernandes, Varley, Fernandes and VarleyFernandes & Varley 1998; see also Reference Durand-Lasserve and SelodDurand-Lasserve & Selod 2007; Reference PaynePayne 1997, Reference Payne2001; Reference RazzazRazzaz 1993; Reference VarleyVarley 2002; Reference Van GelderVan Gelder 2009; UN-Habitat 2003, 2006; Reference Ward and JonesWard 2003). According to this perspective, a diversity of tenure situations exists, ranging from very informal types of possession and use to individual, freehold, ownership, that in some way stand in a hierarchical relation to each other; with the higher-up generally also being regarded as the more secure forms of tenure.

The legal continuum argument, like the legal-illegal dichotomy, generally employs a centralist or state legal perspective, taking official law as the point of departure. Even in cases where religious and customary tenure are taken up into the continuum (see Reference PaynePayne 2001; UN-Habitat 2003, 2006), state law tends to remain the locus of analysis. However, rather than forcing classification into a dichotomy, it designates the legal variations between tenure situations as quantitative differences, in which one situation is “more” legal than another.

The legal continuum idea can take the form of “stacking” formal and informal rights in order to substantiate claims to land (Reference Durand-LasserveDurand-Lasserve 2006; Reference KimKim 2004; Reference KunduKundu 2004; Reference RoquasRoquas 2001). This may be a particularly viable strategy in situations where state agencies are perceived as weak or illegitimate, as these circumstances hinder the effective enforcement of property rights (Reference FitzpatrickFitzpatrick 2006). A telling illustration of such a situation is given by Reference KimKim (2004), who showed that in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, a freehold property right is not the most valuable form of property right because houses with both a property right and another “legal paper” have a higher value and provide more tenure security than houses with just the property right. The author explains that possessing more documentation assists in negotiating one's property right. That is, legal papers alone can be a form of property right enforceable by a state agent, and legal title is superior to the mere possession of legal papers. However, having both is preferable because, rather than the rule of law automatically privileging the title holder, the right must still be negotiated when challenged (Reference KimKim 2004:301).

The Legal Pluralist View

When appeals to different normative orders, and possibly also enforcement mechanisms, are made to substantiate claims, a situation of legal pluralism emerges. Originating in the sociolegal research tradition, legal pluralist perspectives employ the other principal way of conceptualizing informal tenure that deviates from the standard legal-illegal logic. These perspectives argue for the presence of more than one legal or normative order within a certain social field (e.g., a nation-state) and thereby contradict legal centralist perspectives that assume all law to emanate from the state (Reference GriffithsGriffiths 1986; see also Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos 1995; Reference TamanahaTamanaha 2000; Reference Teubner and TeubnerTeubner 1997). Applying legal pluralism to informal settlements requires envisioning them as having proper normative systems with a “law” that is different from and somehow residing outside that of the state legal system. In other words, while the formal or legal city is governed by official norms and legislation, the illegal city is governed by a different set of norms.

Notions of legal pluralism applied to informal settlement have appeared in a number of important studies. In one study, Reference KarstKarst (1971) describes how informal settlement administrations in Caracas's barrios replaced government institutions and dealt with dispute settlement while also functioning as a lawmaking body. He demonstrates how sometimes complex systems of property rights operated in these settlements, concluding that tenure security in the barrio has not been founded on land titles but has instead been the product of an informal legal system (Reference KarstKarst 1971:574). In another classic study, Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos (1977) describes the legal system of a favela in Rio de Janeiro, which also had its proper administration and developed legislative and dispute settlement arrangements. He found that the favelados, aside from using their own informal rules, inventively copied official law where possible and convenient. To deal with the absence of the state as a regulatory body, they had devised adaptive strategies aimed at securing the minimal social ordering of community relations. One such strategy involved the creation of an internal legality, parallel to (and sometimes conflicting with) state legality (Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos 1977:5).

Situations of legal pluralism regarding informal settlement have also been said to arise as a consequence of weak legal systems in which a state de facto does not have a monopoly on the enactment of legal rules, and many actions that are formally governed by official law in reality take place outside its regulatory reach (Reference AzuelaAzuela 1987; Reference Perdomo, Bolívar, Fernandes and VarleyPerdomo & Bolívar 1998; Reference TamanahaTamanaha 2000, Reference Tamanaha2001). According to the legal pluralist view of urban informality, instead of a hierarchy of rights, the difference between the informal and the formal city has a more qualitative nature; they refer to, at least partly, distinct legal realities.

Though in a sense legal pluralism also relies on a dualistic notion to distinguish the legal from the illegal city, a fundamental difference with the dichotomous perspective is that according to legal pluralist notions, one can also observe the binary code of legal communication within informal settlements (see Reference LuhmannLuhmann 1985, Reference Luhmann1989; Reference TeubnerTeubner 1991, Reference Teubner and Teubner1997).Footnote 1 That is, the self-referential use of legal versus illegal in informal settlements is evidentiary of the decoupling of the normative system operative within settlements from the official system and, hence, a situation of legal pluralism, at least as some versions of it, such as autopoietic theory, would have it (e.g., Reference LuhmannLuhmann 1985; Reference Teubner and TeubnerTeubner 1997).

The Present Study

As both alternative perspectives have different points of departure, centralist versus pluralist, and hierarchical versus parallel, the question is how they relate to each other and to what extent they are reconcilable. In this article, taking squatter settlements in Buenos Aires that have their origins in organized land invasions as a point of departure, I propose a framework that integrates the (qualitative) legal pluralist view regarding informal settlement with the (quantitative) legal continuum idea to accommodate the development of these settlements. In particular, I examine the strategies squatters employ to establish security of tenure and their attempts to convert their illegal acts into legal tenure situations in the long run. I show that in this development, the qualitative difference between the formal and the informal city present in legal pluralist conceptions of informal settlement can be “quantified” and phrased into different levels of legality. Conversely, the progressive quantitative steps in the development of a settlement in which it incrementally establishes its legality eventually imply a qualitative change, from the illegal into the legal.

The case of the land invasion is chosen to illustrate the framework because, in comparison to other forms of informal settlement, in their development the opposition between the legal and illegal city manifests itself in its most pronounced way. As Reference AzuelaAzuela (1987:528) notes, the land invasion “represents the ultimate contradiction between a low-income settlement and the legal system. Social consequences of this contradiction are different, and more evident, than in any other mode of land acquisition.” The focus on Buenos Aires is of interest because of the lack of attention given to urban issues and informality in Argentina.Footnote 2 As far as these concerns have been addressed, this has been confined to the interest of Latin American researchers as they are virtually absent in the English-language literature (Reference ZanettaZanetta 2004:5).

Methodology

The empirical data on which this article is based were gathered over four periods of fieldwork between 2004 and 2008, spanning a total of 18 months. Data were principally gathered by means of field observation in canteens and community centers in informal settlements, focus groups and interviews with residents and settlement leaders, and interviews with government officials (on the municipal, provincial and federal level), nongovernmental organization (NGO) representatives, grassroots organizations, and lawyers.

Focus groups with dwellers and settlement leaders were used as the initial research method as they allowed participants to interact and react to each other's statements, which was considered important at this stage of study. Subsequent semi-structured interviews with dwellers and settlement leaders allowed for the clarification and elaboration of issues that had arisen during the focus groups and were to a greater extent based on respondents' lived experiences. Participants were selected on the basis of maximum variation sampling, selecting as much as possible in terms of diversity in background variables such as nationality, age, gender, and life trajectories to ensure generalizability of the findings.Footnote 3 All focus groups and interviews took place in participants' homes or in community centers, and were tape-recorded, transcribed, and coded using similar analysis strategies. To ensure the reliability of the interview and focus group findings, two people analyzed each transcription. The strategy of analysis was to identify main categories within the data collected, discover the relationships between the observations, and ascertain the core concepts capable of describing and capturing the relationships (see Reference RobsonRobson 2002). Analyses were principally based upon three different considerations: (1) frequency, i.e., the number of times a particular issue was raised; (2) the intensity of the comments; and (3) the specificity of the responses. For the focus groups, the degree to which a certain opinion was shared was also a central consideration. Specific, detailed, and shared comments were taken to be based on a greater degree of personal experience and therefore interpreted as more central and relevant.Footnote 4

Field Observation and Analyses

To gain an adequate grasp of the social and physical reality on the ground, the interview and focus group data were supplemented with periods of field observation in community centers and canteens in the selected settlements, generally several days a week during contiguous periods of several weeks. Additional data were gathered by attending meetings between dwellers and government officials, political rallies, and seminars and events on informal habitat organized by NGOs, universities, and government agencies in Buenos Aires, aside from consulting written documentation (e.g., legislation, policy documents, and newspapers). In addition, interviews with government officials, NGOs, and grassroots representatives served to get an idea of the official perspective on informality, examine the extent to which there were differences between municipalities, develop a historical perspective, and contrast opinions of different stakeholders. This kind of data and methodological triangulation served to enhance the validity of the research findings and gain the broadest view possible of the reality on the ground (see Reference DenzinDenzin 1978; Reference Janesick, Denzin and LincolnJanesick 2000).

The combination of methods chosen was partly theory driven and partly based on grounded theory, i.e., data-driven analysis strategies with the goal of “discovering what is really going on” and generating theory from the data instead of the reverse (Reference GlaserGlaser 1998; Reference Glaser and StraussGlaser & Strauss 1967). The rationale for this approach lies in the fact that there was no clear theoretical framework pertaining to the development of land invasions that could be used as a point of departure. Consistent with the emergent character of grounded theory methods, the analyses evolved over the course of data collection and interpretation. Because each fieldwork period was followed by a period of analysis, it enabled the systematization of the provisional research results of each period and the generation of new research questions to be examined during a subsequent period.

Choice of Settlements

All settlements studied were land invasions, which are to be distinguished from other kinds of low-income settlement (to be explained shortly), located in the urban periphery of the city, the Conurbano. As disparities between the various parts of a city, particularly a metropolis like Buenos Aires, pressure a research project for samples that are sensitive to these differences, 10 settlements that together were assumed to reflect the variety of land invasions in the city were selected. The selected settlements varied in size (from around 50 to 800 lots), degree of consolidation (more recent versus older settlements), geographical location (different municipalities), and degree of formality (from lacking legal status to legalized). Note that instead of looking at the settlements as isolated cases, the analyses were informed by the idea of finding similarities and common denominators. Therefore, a central consideration regarded the degree to which opinions and processes were shared not only by dwellers within the settlements studied, but also between them.

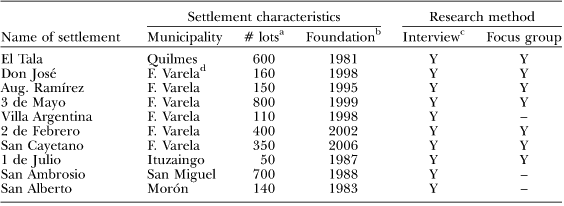

Systematic field research that included both focus groups and interviews with dwellers and settlements leaders was carried out in seven settlements. In three settlements (San Alberto, Villa Argentina, and San Ambrosio), only interviews were held. Settlement characteristics, i.e., municipality in which the settlement was located, year of foundation, and estimated number of lots per settlement are presented in Table 1.Footnote 5

Table 1. Settlement Characteristics and Research Method Employed in Participating Settlements

Notes:

a estimated number of lots in the settlement,

b year of invasion,

c Y=yes,

d Florencio Varela.

Context: Crises and Informality in Buenos Aires

Origins of Informality

Even though the first squatter settlements in Buenos Aires date back to the 1930s, as a housing alternative they only started to gain significance in the 1950s (Reference Cravino and NeufeldCravino 1998). Until then, informality had been limited in size and mainly transitional in nature. In the early days, the settlements provided a temporary habitat for European immigrants during a period of relative economic prosperity. The newcomers were generally able to move to legal housing within a few years after their arrival in the city due to abundant employment opportunities, enabling land use legislation and the availability of land in the periphery of the city (Reference TorresTorres 1975).Footnote 6

Import-substitution policies in the 1950s led to the deterioration of the country's rural economies and the concentration of industry in and around Buenos Aires, which caused an influx of migrants from the interior provinces (Reference TorresTorres 1975). The new rural-urban migration amounted to 200,000 individuals coming to the city every year during the late 1940s and early 1950s (Reference KeelingKeeling 1996: n.p.). Between 1947 and 1960, the population of Greater Buenos Aires more than doubled, and in spite of high government expenditures on social housing, the construction of dwellings was simply outpaced by the size of the migration (Reference KeelingKeeling 1996: n.p.). Poor immigrants from neighboring countries such as Paraguay and Bolivia started to settle in the city's informal settlements in large numbers in the 1960s, and with the progressive deterioration of the economy in the second half of the century, informality became increasingly widespread and also a more permanent phenomenon (Reference CravinoCravino 2006). According to Reference YujnovskyYujnovsky (1984: n.p.), the population of Buenos Aires' slum settlements grew more than 8 percent per year on average between 1950 and 1970.

The original squatter settlements were coined villas miseria Footnote 7 and occupied vacant, and generally public, land in violation of planning regulations and had a highly irregular structure with unpaved, narrow and winding alleys and inferior living conditions (Reference CravinoCravino 2006). With the state absent as a regulatory body, dwellers created internal organizations to regulate daily life in their settlements. Interestingly, the first resident organizations evolved from soccer clubs, which stimulated contacts between dwellers and encouraged community participation (Reference ZiccardiZiccardi 1983). Furthermore, the creation of leagues and tournaments in which teams from different villas participated strengthened group identity and contributed to more complex forms of organization (Reference ZiccardiZiccardi 1983).

Dictatorship and Neoliberalism

The military government that took power in 1976 embarked on a program to eradicate all slums in the Federal District, reducing their population from more than 200,000 to little more than 10,000, and imprisoning and “disappearing” many settlement leaders (Reference CuenyaCuenya 1993). Also under the junta, Provincial Land Use Law 8.912 was enacted in 1977. In an attempt to curb the rampant spread of low-income land subdivisions in the urban periphery, the sparsely serviced loteos populares, and to regain control over urban development, this law prescribed new standards and forbade lots without services and infrastructure. This greatly increased the cost of land and led to the effective suspension of the authorization of new loteos. Because people were also being denied housing alternatives in the central areas of the city, they increasingly sought shelter in its periphery in the form of organized land invasions, known as asentamientos.

With the return of democracy in 1983, repression against illegal land occupation was somewhat relieved, while legislation unfavorable to the housing options of the popular sectors remained, thus contributing to more informality (Reference Cravino and NeufeldCravino 1998). In 1989, Argentina's economy was on the verge of collapse, inflation had reached an annual level of 5,000 percent, and the urban economy had become smaller than it had been in 1970 (Reference KeelingKeeling 1996: n.p.). In response, a reform program announced as “surgery without anesthesia,” which included the sale of state enterprises, privatization of public services, and state disengagement from the economy, was put into effect (Reference ZanettaZanetta 2004). These policies threw open the door for international actors to participate in economic activities, such as the provision of public services and land operations, thus encouraging property speculation, intensifying the commercialization of urban land, and pushing up land values and, consequently, catalyzing informality (Reference ClichevskyClichevsky 1999).

In the 1990s, in line with the neoliberal current of the era, a change in government policy toward illegal land occupations came about. The largely ineffective existing social housing programs were abandoned in favor of policy based on the allocation of property rights to squatters, and national legislation was approved to provide the legal framework for the regularization of illegal tenure, on both state and private land.Footnote 8 However, little progress was made toward the implementation of this legislation. Furthermore, the fact that eradications also continued on a regular basis testified to a lack of integrated land and housing policy.

The 2001 Breakdown and Subsequent Recovery

To maintain macroeconomic stability, the government increasingly relied on external moneylenders, and the country faced mounting debt. The economy slowed and ultimately fell into depression. At the turn of the millennium, social protest exploded with sieges of government buildings and courthouses, almost daily blockades of roads and bridges in central Buenos Aires, and the looting of supermarkets (Reference Auyero, Fernández-Kelly and ShefnerAuyero 2005). In December 2001, Argentina declared default—the largest in world history—on its foreign debts and by 2002, more than half of the population lived under the poverty line (Reference Fidel and CuenyaFidel 2004: n.p.).

Since 2003, the country has been recovering, and annual GDP growth averaged 9 percent per annum between 2003 and 2008 (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censos [INDEC] 2008; http://www.indec.mecon.gov.ar, accessed 23 Feb. 2008). By 2005, the government had restructured its external debt and paid off its International Monetary Fund obligations. Unemployment also dropped significantly. In 2004, a new national social housing program was initiated (the Plan Federal de Construcción de Viviendas), but even though the program implies an important departure from earlier programs in terms of scale, it has various deficits as houses are built on land far from the city's central areas and sources of income, which reinforces urban segregation, and it suffers from severe backlogs. Particularly in Buenos Aires, few dwellings have been completed under the program (“La pesadilla de la casa propia,”Crítica, 6 July 2008).

In spite of arrested urbanization, GDP growth, tenure regularization legislation, and significant government expenditures on social housing in recent years, informality in the city increased by more than 2 percent per year between 2003 and 2008 (INDEC 2008; http://www.indec.mecon.gov.ar, accessed 23 Feb. 2008). According to the most recent data, the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires has around 800 informal settlements, together housing just over 1 million people (Info-Hábitat 2007: n.p.).

The Land Invasion in Buenos Aires: From Control to Legality

The Genesis of the Asentamiento as a Housing Strategy

The laws and policies of the last military junta, in combination with the economic downturn that marked the era, had created a situation in which people were increasingly pushed into poverty and from the city's central areas toward the periphery, where the first land invasions occurred in the early 1980s. These asentamientos differed from the villas miseria in a variety of ways. Instead of being the result of a gradual and unplanned occupation, the asentamiento was produced by an instantaneous invasion in which squatters collectively invaded a vacant tract of land, parceled it out, and immediately built precarious dwellings on the site. Furthermore, the settlements differed in form as the densely populated villa had a chaotic and ad hoc appearance, whereas the asentamiento had a clearly defined layout, with parceled lots in line with the grid structure of the city and land use legislation. Furthermore, while villas could be found in the urban core, close to centers of production and consumption, asentamientos were only encountered in the periphery.

A clear logic explains the spatial and organizational form the asentamientos took. For one thing, the early asentamientos formed a defensive strategy against a repressive state, whose primary response to informal settlement was eradication. Collective and organized alternatives had better cards for resisting the coercive hand of the state, in comparison to individual occupation, due to their critical mass and social organization. In addition, asentamientos are from their genesis onward directed at their regularization and actively try to establish their legality, which explains why they attempt to conform to land use legislation. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that almost immediately after the production of loteos was effectively suspended as a consequence of Law 8.912/77, people started to generate informal settlements that in form and development were very similar to them: empty lots without infrastructure in the urban periphery where dwellings begin as precarious units that are gradually improved over time. Finally, the fact that land invasions have predominantly been undertaken by young urban families indicates that this kind of informality results from an impoverished urban population faced with land use legislation and policy detrimental to its housing needs, rather than from mass rural-urban migration.

Two Goals

Asentamientos follow similar patterns in their development, starting with the organization prior to the invasion and ending, without exception, after a long and arduous struggle, with the legalization of the land claims. In this process, there are two fundamental, and in a sense sequential, goals. The first is to generate tenure security; the second regards the legalization of tenure. As I discuss, both goals depend on the internal organization of a settlement and on the way it relates to the state and the legal system, which are separate but interdependent processes.

In order to reach the first goal, the emphasis lies on processes internal to the settlement—e.g., keeping conflict between settlers to a minimum, maintaining social cohesion, and establishing settlement organization and leadership—and success depends primarily on the settlers' ability to control land and deal with repression and threats by state actors. Reaching the second goal depends on the ability of a settlement to adapt to the state system, meeting the requirements it poses for legalization—and therefore becoming conversant in its laws and policies—and pressuring it to undertake steps toward this end. As such, a settlement's strategy shifts from resistance and noncompliance in the early phases of development to adaptation and adjustment in subsequent stages. As I explain, initial resistance against the official system is, paradoxically, a precondition for reaching the second goal and being incorporated into the legal city.

Below I give a generic description of the development process of land invasions in terms of the successive phases they pass through and their particular characteristics. Even though each process is unique and not all land invasions pass through the details of each step, the general logic of the model presented below is always present.

The Internal: Generating Security of Tenure

Getting Started

Before an invasion is actually performed, there is generally some kind of prior organization, which often involves outsiders such as grassroots organizations, church groups, lawyers, or members of social protest movements who assist the occupiers with getting organized, selecting a property to invade, parceling out the land, and other technical elements to render its regularization at a later stage possible.

During the preparatory phase, land registers may be checked to get information on the dimensions of the land, its legal status, and its owner. The objective is to seek out land that has a low chance of generating (intense) conflict. Invasions on state land have a higher chance of success than those on private land because without an individual interest affected there is also less incentive to react, and also because of the high political cost forced evictions can carry. However, vacant state land has become scarce in many areas in Buenos Aires, and squatters have resorted to occupying private land with some kind of legal problem regarding the ownership of the property, such as succession problems or high tax debts. Occupying land that appears abandoned is another option that is less prone to evoke contestation.Footnote 9 Political or otherwise strategic events may also be capitalized upon. Invasions may, for example, be planned around elections, capitalizing on the political cost of eradication, which is particularly high in areas where informal dwellers constitute a substantial part of the voting public.

The invasion itself, often taking place overnight so as not to attract (police) attention, essentially consists of cleaning up a vacant tract of land, parceling it out, and allocating the lots to the participants, usually a few hundred families, who immediately build precarious dwellings. The goal is to create facts on the ground fast and exercise control over the land. Immediate development presents the authorities with a fait accompli that reduces the risk of eviction. Another factor increasing tenure security is the number of individuals involved. The greater their number, the more critical mass they assemble and the less likely their eviction.

It is not uncommon for asentamientos to be conducted with little or virtually no prior planning. However, the preparatory phase is often crucial, as a lack of planning and organization not only means a weakened ability to confront state actors in the face of attempts at eviction, but also renders it difficult for state agencies to intervene in support of the squatters. Furthermore, when spatial features such as lot dimensions and roads do not have a regular form and do not meet the prescriptions of land use legislation, problems emerge in the long run with the regularization of a settlement. There is much variation between settlements in this respect. As one grassroots leader related: “In ten years time an asentamiento may have either deteriorated and turned into a villa, or, to the best of their abilities the residents have improved it, opened roads, got connected to the electricity network, got water, made sidewalks, a plaza, a school …” (Ariel Luna, interview, July 2005).

The Comisión

Once the control of the land is a fact, the spatial features of the asentamiento are established and a second phase with two defining parameters starts: internal organization to establish social order, and the establishment of ties with the environment (Reference MerklenMerklen 1997).

During the first days following the invasion, which are generally characterized by substantial chaos, threats of eviction and, potentially, police violence, the first form of internal organization and neighborhood leadership tends to crystallize. Residents of each parceled “housing block” vote in their representative in a body of delegates, which in turn elects a neighborhood administration known as the Comisión or Junta Vecinal. For decisions that concern the settlement, assemblies where dwellers meet for a public discussion may be called. While the Comisión forms the “executive branch,” assemblies have been termed the “legislative branch” of the asentamiento (Reference MerklenMerklen 1997). The “jurisdiction” of the Comisión is limited and principally concerns matters related to habitat, infrastructure, and service provision, and possibly also dispute settlement.

Whereas by assembling critical mass and creating facts on the ground the land invasion is established physically and (still precarious) tenure security is generated, with the formation of an administrative body the first distinction between the internal legal order of the settlement and the external state legal order emerges. Note that here too there is much variation between settlements. Some Comisiónes function according to the precepts of democratic governance, whereas in others social organization may be virtually absent or contested.

Given that tenure insecurity is high directly after the invasion, squatters can use various strategies to mobilize third parties for their cause. It is, first, important to get some kind of political protection, and therefore the squatters may approach a local politician to mediate in the land conflict. Second, settlers may try to get coverage of the event by local media, such as newspapers and television stations. Doing so means posing limits to potential police violence. Third, the presence of priests or government officials during or after the invasion also limits police repression and contributes to the perceived legitimacy of the invasion. Raúl Berardo, the priest who helped organize the first, heavily repressed, land invasions in Buenos Aires related:

I put up two signs to take away their [the squatters'] fear. I posted the Argentinean flag and a sculpture of the Holy Virgin, you see, as symbols, and told them: “You are Argentinean and you have a right to your land. You can't be a stranger in this or whatever other part of the country. God gave these lands to everybody. Who bought them from God? So, if you are a child of God, you also have a right to a piece of land.” So the Holy Virgin and the flag were symbols that helped empower the people, you see? (Interview, July 2005)

Control, De Facto Tenure Security, and Semi-Autonomy

When a settlement, generally within a period of several months, has created facts on the ground, formed a representative body, made its existence known to the outside world, and has not been eradicated, its first goal, that of establishing tenure security, has been met. In the absence of legal status, this de facto security is still precarious, based on critical mass and internal organization, which ensure the effective control of the land, possibly in combination with the mobilization of third parties.

The border between “the inside” and “the outside” of a settlement, indicative of a situation of legal pluralism, is clearly established during this phase. With respect to the inside, Karst's observations of the legal workings of informal settlements in Caracas, Venezuela, are worth quoting as they apply equally to the case of Buenos Aires:

The security that matters is the barrio resident's expectation about the future. We are accustomed to think of the law's contribution to the security of tenure in formal terms: the title to land, established by reference to authoritative documents, gives the owner access to the state's coercive power to protect him against dispossession. The strong sense of security in the barrios, however, plainly does not rest on title. Then what are its sources?

The barrio resident, to feel secure, must be assured against two kinds of threat: those that may arise from within the barrio and those that may come from outside. Neighbors in the barrio do generally respect one another's ownership rights; there is no need to post a guard to defend one's possession. Furthermore, the rights of a barrio house owner are enforced by the barrio junta in a number of well-defined situations, in a system of community-wide universality and uniformity that deserves to be called law. […] Within the barrio […] a squatter's security of tenure rests on the barrio's informal legal system (1971:568–9; emphasis in original).

Paradoxically, while illegal land occupations constitute a deliberate violation of property rights on the one hand, they simultaneously support the concept of private property on the other. Rather than being mere acts of defiance against the legal system, settlements actually espouse a system of private property rights by generating alternative systems of such rights in the absence of state recognition. Initially, the actual control of a plot of land by erecting a dwelling and fencing it, and recognition by other dwellers, testifies to the existence of a property right even though this right lacks official status. In some cases these rights remain unwritten, but in others informal deeds attest to ownership and accompany the sale of dwellings, and settlers may also keep registers containing information regarding who occupies—or “owns”—what plot. Despite lacking formal legal validity, these agreements and documents have weight in the settlement as their contractual aspects are generally upheld. Basically, any kind of document, such as an (informal) purchase contract, an electricity bill or a school report on which the name of the street given by the dwellers appears, or even a receipt attesting inclusion in a national census, is used by residents as evidence of “ownership” and adds to perceptions of tenure security and legitimacy.

When the state eventually decides to legalize a settlement, it often builds on its existing informal legal structure and institutions: for example, by using the property registers of the settlement, thereby formalizing the informal “real estate” system. Formalizing the role of a Comisión is another example of how the state may use the informal arrangements within a settlement in the legalization process (explained shortly herein).

Even though informal legal systems in settlements substitute for various functions of the state legal system, they are never completely autonomous or “sovereign.” The particular conditions that create settlements forcibly involve them with the city, and they are compelled to acculturate strategically in order to defend themselves (Reference ManginMangin 1967) and to gain and maintain access to the state's resources. Informal settlements, therefore, bear strong resemblance to the notion of the “semi-autonomous social field” (SASF) (Reference MooreMoore 1973). This network of social relations has rulemaking capacities and the means to induce or coerce compliance, but it is simultaneously set in a larger social matrix that can and does invade it (Reference MooreMoore 1973:720). Like an SASF, a settlement generates its proper rules, customs, and symbols internally, but as the name suggests, it is also vulnerable to rules and decisions and other forces emanating from the larger world by which it is surrounded (Reference MooreMoore 1973:720).

Legitimacy and Contestation

When asked about the basis of their convictions regarding their tenure and land ownership, settlers cite a variety of reasons that partly coincide with law, but in some respects follow a logic of their own. Residents regularly make the distinction between the ownership of the land they occupy, which they concede belongs not to them and which they consider to be an issue to be resolved in some near or distant future, and the ownership of the dwelling they have built on it, which they generally consider to be legitimately theirs because it is the result of their “proper” investment.Footnote 10

Similar discrepancies in legal reasoning are also found with respect to criminal law. From the dwellers' perspective, the disposition to pay for the land, as long as it is within their financial means, puts them outside the scope of (committing a) criminal offense and legitimizes the occupation. That is, even though they are aware of the fact that their practices directly violate official law, they are convinced that the violation is justified. Again, the concept of private property as such is not questioned; rather, its reaches and implications are (Reference Fara and JelinFara 1985). Moral notions may also be brought forward to justify occupations. This is evidenced by popular slogans in the discourse of residents such as: “Maybe it is illegal what we do, but it is legitimate” and “We don't want to be given anything. We just want to buy what is ours.” In the view of the dwellers, the occupation is justified on the basis of the necessity to have a place to live in the city and their disposition to pay for the land.

As discussed earlier, the informal system is disconnected from the formal system only in certain ways, while in others they are deeply intertwined. Even though the legitimacy of property inside settlements is represented not by a registered title deed or formal rights but by a set of informal ownership rights, this does not mean that settlers display a complete disregard for formal rights or deny the role of the state as a rule maker. As much as it is clear that an occupant considers him- or herself to be owner, it is also clear that he or she is aware of an official system of property rights with which he or she does not comply and which means that tenure security is not complete. Full ownership of land requires a registered title deed, the escritura, and anything less implies imperfect ownership. Although the state cannot inhibit the settlers' control over the land and has also been incapable ex ante to protect the property of the landowner, it does have the capacity to define and respond to the conflict in its own terms: that of the legal system. Furthermore, the state still retains substantial and often quite arbitrary discretionary powers over life in the settlement, and it can effectively delay or deny access to public resources such as services and infrastructure, health care, policing, and regularization. Hence, a main limitation of the informal system and its reliance on de facto tenure security is that it remains vulnerable to changes in government policy. As explained in the following section, the protection against eviction, in the absence of legal safeguards, may still depend on local political patronage and clientelist relations with officials (see also Reference Durand-LasserveDurand-Lasserve 2006; Reference SmartSmart 1986). For these and other reasons, most residents aspire to the legalization of their settlement. To get there, settlers will need to further its legality and attempt to define it in official legal terms.

The External: Toward Legalization

Once the informal settlement has been established and de facto tenure security generated, the second goal of the land invasion gains prominence and residents actively start developing strategies directed at the legalization of their tenure. The focus in this phase, therefore, gradually shifts from processes internal to the settlement toward its external environment during a development in which an open conflict is transformed into a legal one.

Servicing

In the period directly following an invasion, squatters generally obtain services through illegal hookups to existing networks or through improvised measures. The precarious nature of these self-help services leads settlers to pressure the state to service their settlement—for example, by organizing pickets or sit-ins at the city hall. Once the first official services (or infrastructure) enter a settlement, residents interpret it as implying, or at least contributing to, official recognition, which adds to both feelings of legitimacy and perceptions of tenure security, knowing that it is unlikely that the state will destruct infrastructure it has contributed to itself (see also Reference AngelAngel 1983; Reference GilbertGilbert 2002; Reference PaynePayne 1997, Reference Payne2001). As such, the introduction of services also generates a secondary effect as it testifies to the (implicit) official acknowledgment of (the existence of) the settlement.

Note that services generally enter a settlement only gradually and only after considerable effort on the part of the settlers. As Reference Gilbert, Baróss and Van Der LindenGilbert (1990) writes, the illegality of a settlement constitutes a way of dispensing services for favors and is also a method of rationing services, as governments can attribute the absence of services to the illegality of a settlement.

Legitimating Control

Another important step in the development of an asentamiento is for its administration to obtain legal personality. With this step the authority and legitimacy of the Comisión derive not only from its status within the settlement, but also from the explicit recognition by the state system. State institutions may support, and sometimes even exact, the creation of a legal entity in order to legitimize their relationships with the settlement.

Legal Strategies: Beyond Legitimacy

To proceed on its path toward regularization, a settlement needs to develop a “legal” strategy. As Reference RazzazRazzaz (1993) notes, a central conditioning element of informal access to land regards the relative ease of possession and the possibility of gaining de facto control, which makes this control particularly prone to contestation. However, as mentioned earlier, even though squatters may exert enough real power to be able to develop the land in a way prohibited by law, their control always needs to be legitimized through appeals to some kind of legal norm (Reference AzuelaAzuela 1987), which sets it apart from other kinds of collective illegal practices (such as a gang). Appeals to human rights notions, such as the right to adequate housing, can form the counterclaims to the landowners' property right. Even though not adequate to win the land dispute in court, these appeals are necessary, because the state needs some kind of normative framework to justify its interventions and tapping into official law opens up the road for a legal solution to the conflict. With the argument that the legitimacy of the settlement should take precedence over alternative legal claims, such as the violation of property, settlers invoke not only a conflict of rights but also a conflict in law—invoking higher-order law (human rights law) over the law of the state.Footnote 11

The direct and strategic invocation of civil law to substantiate land claims is an alternative, and possibly complementary, approach to human rights appeals. Here the squatters' strategies can be modeled on the same laws they violate. For example, when confronted with claims contesting the legality of their possession, squatters may produce documents such as fake title deeds to support their own claims.Footnote 12 These documents attest to the “good faith” of an occupant who can argue to have been the victim of a scam, which in some cases may be true (and in others not), and who thought he or she had gained legal access to the land. Furthermore, squatters may remove fencing around a piece of land months prior to an invasion in order to clear marks of a forced entry and thereby, besides verifying whether the owner is checking up on the land and estimating the probability of legal action, demonstrate “peaceful” entry. These strategies entail a change in squatters' legal status from usurpers to possessors in good faith, help them avoid penal charges, and imply that potential eviction changes from an immediate issue into a long-term one due to the lengthy legal processes in Argentina's slow courts.

Finally, people invoke official law not only for fraudulent purposes but also to bring the land conflict into the legal arena precisely in order to keep it unresolved—yet contained—by limiting the options of the state and the landowner to respond with force, until the political will is found for a solution (Reference HolstonHolston 1991). Here, law offers both a stage and a language of resistance, and the adoption of a legal vocabulary permits engagement in terms that the state is obliged to understand, forces it to justify its actions, and effectively enforces delays in interventions that may be detrimental to the squatters (Reference JonesJones 1998:506). Note how these appeals underscore the difficulty of maintaining a rigid distinction between the “illegal” and the “legal” and the invalidity of perspectives that perceive informal settlements to reside entirely outside the legal realm, as they actually appeal to official legal standards and provisions.

Expropriation

Given the legal ambiguity of the situation and/or the political infeasibility to evict, often the land conflict is ultimately resolved through a politico-administrative action. The observations of Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos (1995:386) regarding land invasions in Recife, Brazil, bear strong resemblance to the case of Buenos Aires:

The general characteristic of the legal strategies designed […] is that the legal defense must always be articulated with a political defense, so that both defenses are mutually reinforced. […] [G]iven the overall class character of state laws on land property and housing, the initial legal position of the urban subordinate classes is, in most conflicts, and in strict legal terms, a rather weak one. If the state legal system alone is allowed to control the definition of the conflict, there is very little that can be done on this terrain to defend the interests of the urban poor, and less so in view of the conservative ideology of the judiciary.

The most commonly used instrument in Buenos Aires has been to vote in an expropriation law in which the landowner is expropriated on grounds of public interest and the state is under the obligation to indemnify the landowner for the loss of his or her land within a specified term, generally two to five years.Footnote 13 When this period lapses and the state has not compensated the landowner, the law expires and the squatters are once again subject to eviction, although a law can be extended. The director of the Subsecretary of Urban Housing of Buenos Aires Province explained the defects of the expropriation practice:

Expropriation is an easy mechanism for the legislature and for political brokers. […] For years now this has been the kind of politics typical of the legislature of the Province of Buenos Aires that kept people quiet because they were waiting for a law to be passed for their settlement. Then when the delegate who built his fame and reputation on these laws disappears from the political stage, the laws are sent to the executive power. But they are not executable because there are no funds to buy land. Generally, the ministers of economy do not want this amount of money to be spent on buying land, and I have no budget for it (Alfredo Garay, interview, August 2005).

Even though this state of affairs keeps residents in a situation of legal uncertainty, it can be of strategic use precisely because it keeps the land conflict unresolved. During the period in which the law is in force, residents cannot be evicted and a settlement continues to consolidate. Even though a settlement formally once again faces the threat of eviction when the law expires, the de facto tenure security has improved significantly during the period in which the law was in force due to the consolidation of the settlement and its increased legitimacy. The short-term legal protection increases de facto tenure security that remains even when the former collapses. The advantages this situation offers to dwellers were explained by a well-informed grassroots leader:

One thing you have got to understand about asentamientos is that for a long period you get your lighting and your water for free. You don't pay for it, nor do you pay any taxes. For the people who still preserve the belief in the possibility of socioeconomic progress, this is an opportunity. So they invest this money they save not paying [for] these things in their homes (Alberto Fredes, interview, April 2005).

Essentially, the initial illegality of a settlement enables low-income dwellers to access a plot that would otherwise be beyond their means (Reference Gilbert, Baróss and Van Der LindenGilbert 1990). The rearranging of the sequence of land development from planning-servicing-building-occupation to occupation-building-servicing-planning (Reference Baróss, Baróss and Van Der LindenBaróss 1990) allows for the allocation of the limited resources of dwellers to the consolidation of their dwellings. Legalization, then, is only the last step of a lengthy process at the end of which only very few characteristics distinguish a settlement from the legal city.

Legal Ambiguity, Clientelsm, and Political Brokerage

According to Reference FitzpatrickFitzpatrick (2006), interactions between property rights systems occur in colonial and postcolonial contexts where modern and traditional legal systems compete with each other. It can be argued that they apply to squatter settlements as well. Landowners rely on the authority of the state and the official legal system to enforce their property rights, but state agencies are unable to entirely exclude squatters who take possession of and control property. Squatters, in turn, can partially disregard official rules and institutions, but their informal normative orders are incapable of replacing all the vital functions of the state, and the power of settlement institutions is limited and confined to specific areas. Perhaps even more important is a settlement's dependency on state actors and agencies for its development and the fact that tenure security always remains partial without full legality, as sociopolitical pacts against eviction and official toleration of informal occupations are vulnerable to change (Reference Van GelderVan Gelder 2010).

The ambiguity that characterizes this situation, fueled by the lack of consistent policy toward informal settlement in Buenos Aires, leads processes of state intervention to be subject to clientelist practices in which servicing and settlement upgrading are presented as favors granted to settlers, instead of being an expression of their rights. Capitalizing on the opportunity for manipulation, local politicians have become heavily involved in barrio politics by attempting to co-opt neighborhood organizations and their leaders, appointing political brokers, and sometimes creating their own administrative units in settlements. Co-optation and brokerage operate through the promise of favors or privileges (e.g., goods, jobs, permits, and services) and the use of state apparatus by political figures in exchange for votes, help in political campaigns and rallies, or other forms of support (Reference GazzoliGazzoli 1996; see also Reference AuyeroAuyero 2000, Reference Auyero2001). Although not limited to constituency-building in informal settlements, these communities are particularly susceptible to clientelist practices due to both the dependent position of the settlements as long as the legal status of their tenure has not been resolved and the indigence of the population.

As summed up by Reference MiraftabMiraftab (1997:303), for the poor, informal homeownership is an affordable and feasible way to secure shelter. For the state, the illegality of settlements and dwellers' need for services and legal tenure presents an opportunity for political manipulation. As such, there is little incentive to actively engage in the regularization of informal settlements. A grassroots leader and former municipal councilman explained the mechanism in his municipality as follows:

First there is this attitude of spending as little as possible. You know, like “if they [the squatters] don't bother us, then let them just stay where they are and go to hell.” That is the first thing they do. Not attend, not allow access to the state. Then, when leadership capable of raising certain issues emerges in a settlement, the primary reaction is to see how it can be neutralized. Anything they can do through the use of the state apparatus. When they see this is impossible, there appears this person, coming to you […]. Maybe he knows you or maybe he knows how to get to you, and he starts offering you things; money, a job at the municipality … (José Luis Calegari, interview, December 2007).

Without Papers It's Like We Don't Exist Either

In spite of the potential advantages of informality mentioned earlier and the de facto tenure security generated by the informal legal system, dwellers generally do aspire to the legalization of their tenure in the long run. One of the most salient reasons for the importance of homeownership by low-income groups regards the access to a stable asset that steadily increases in value in a society where social and economic ascent have become progressively prohibitive due to a weak capital market, an inflationary economy, successive crises, a dismantled social security system, and high levels of unemployment. A title deed, which forms the coronation of an effort to secure a plot, build a house, and develop family life after years of struggle, is something substantial, tangible, and secure that can be passed on to future generations. One dweller phrased it as follows: “I think that we, asentados [squatters], value a property title more than some guy from the middle class who just buys his plot, mortgages it, and registers it. Because for us it has been a struggle, losing lives […], facing up to heaps of problems, and continuing to fight” (Focus group discussion, June 2008).

As Reference DoebeleDoebele (1977:552) remarks, being an owner implies access to respectability and status in a social order that offers very little of either. Indeed, one of the most prominent properties dwellers attribute to their informality, an issue that surged again and again during interviews and focus groups, was the negative psychological effect of being illegal (see Reference Van GelderVan Gelder et al. 2005). For residents, having a property title, realistically or not, implies inclusion in a society that has systematically denied them entry. As one resident put it: “Without papers it's like we don't exist either” (Focus group discussion, July 2004).

Getting Stuck in the Middle: The Dissolution of the Informal Legal System

When the land conflict itself has been resolved, for instance because the state has indemnified the landowner, a settlement has again moved up a notch on its path to full legality, but it is still far removed from the actual completion of the regularization of the land which inter alia requires spatial intervention, permission for the (legal) subdivision of the property, and often decrees and ordinances that allow for exceptions to the land use legislation in force. In a trajectory that takes years to complete, a great many bureaucratic obstacles need to be overcome to complete all necessary steps and acquire the necessary permits and authorizations from the various government agencies involved.

Discussion

Land invasions have emerged in Buenos Aires in a context of economic downturn, and different laws and government policies that have made legal access to land and housing for the popular sectors increasingly difficult. With formal housing options denied to them, these sectors have resorted to alternative strategies to secure tenure, creating settlements with proper normative systems operating parallel to those of the state and often contradicting them. The settlements originate in a violation of state law and develop by resisting the coercive authority of the state and attempts at eviction. In order to gain subsequent entry into the official legal system, they exchange resistance for adaptation and develop strategies to increase legitimacy. In other words, while initially resisting the state system, the settlement adapts to it in later stages. Instead of being static, the settlement-state relationship is dynamic: The intermediate steps in this process make it a quantitative phenomenon on the one hand, as establishing legality is a gradual endeavor, and a qualitative one on the other, as the settlement eventually trades its informal possession for formal ownership. Paradoxically, initial noncompliance with the official legal system is a requisite for gaining entry into it at a later stage.

At its inception, the emphasis in strategy lies on establishing (de facto) tenure security—primarily based on critical mass, the actual control of land, and informal organization—and resisting state pressure. Once this is achieved, the focus shifts toward gaining infrastructure and services and the further adaptation to the official requirements that render regularization possible. In the long run, few alternatives may be left for the government but to accept the situation and legalize the informal tenure arrangements. In this protracted and cumbersome process, the internal normative system is gradually dismantled and replaced by formal law. Yet due to lengthy, highly bureaucratic legalization procedures that lack transparency, and political co-optation and clientelism, many settlements get “stuck in the middle,” not being illegal anymore but still lacking individual property titles and therefore not achieving full legality either.

Theory Revisited

The main theoretical point this article set out to make was that perspectives that designate tenure as either legal or illegal obscure the variety of situations one encounters in cities in the developing world, the legality within informal settlements, and the often complex, contradictory, and dynamic relationships they entertain with the state legal system. As I argued in the introduction, the legal continuum idea with its different levels of legality resolves some of the problems associated with the legal-illegal dichotomy, as it is better capable of accommodating the variety of tenure situations. However, the legal continuum idea does not deal with the developing nature of squatter settlements, nor does it satisfactorily capture the parallel legality of settlements with proper normative systems and state law.Footnote 14

Straightforward legal pluralist perspectives with respect to informal settlement, though overcoming some of the (other) inherent problems of the legal–illegal dichotomy, may not adequately depict the phenomena under study either. As Reference BentonBenton (1994:225) notes, “[t]he legal foundations of the informal sector are themselves rarely closely examined. Instead, analyses simply assume a legal pluralist framework of the most purely structural kind: a framework of levels of law that ‘stacks’ the formal and informal sectors one atop the other.” With some important exceptions (e.g., Reference De Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos 1995; Reference RazzazRazzaz 1994), studies on informality only rarely deal with the progressive and developing nature of informal settlements and rarely refer to the diversity in kinds of tenure. In addition, a recurrent point of controversy in the literature on legal pluralism is whether one should actually speak of multiple legal realities or fields, as formal law continues to pervade social relations, also in the informal sector, which often makes it difficult to distinguish legal norms from social norms (e.g., Reference TamanahaTamanaha 2000). With respect to tenure informality, the developing nature of land invasions shows that legal pluralism is particularly prominent in the early stages of settlement formation. Over time a settlement increasingly becomes interwoven with the official legal system, until the two systems finally merge when a settlement is legalized.

In this article, I have shown that a perspective that integrates the legal pluralist perspective with the legal continuum idea adequately captures the development of informal settlements and the relation between these settlements and the state system, and can overcome the shortcomings of both perspectives. Future studies of informality in other contexts, whether sociolegal or developmental in nature, may therefore benefit by applying the framework presented in the present article.