INTRODUCTION

In the years immediately following the unification of Italy in 1861, one of the main issues in debates on criminality and punishment concerned the possibility of establishing penal colonies, isolated places where convicts could be confined and “rehabilitated” through the use of outside work programmes. In particular, some penologists and members of the influential agrarian class supported “internal colonization”, that is, the establishment of penal colonies within national borders so as to reclaim wastelands that could be improved and “exploited” using convict labour.Footnote 1 The development of Italian agricultural penal colonies is emblematic of the history of forced labour in the country, principally because of its objectives, namely colonization and the valorization of the land, activities at the centre of the social and economic objectives of first Liberal and then Fascist Italy.

In this article, I analyse Italy's agricultural penal colonies, mainly focusing on their margins and borders, viewing them from different perspectives.Footnote 2 Archival records on prison administration show that the story of penitentiary colonies within Italy's national borders overlaps with that of its penal colonies overseas. Documents on Italy's internal colonies and those relating to its overseas colonies comprise a single discourse on agricultural colonization.Footnote 3 In the first section, I consider the frontier between Italy and its overseas territories, as represented in discussions regarding the location of penal colonies in the first decades following Italian unification. This debate allows us to capture some of the most important traits of Italian penitentiary colonization. Among other aspects, I highlight some of the factors that determined the lack of deportations and transportation of Italians overseas in the country's history of forced labour.

For the most part, I analyse penal colonization and the development of penal agricultural colonies in Italy in terms of the interconnection between metropole and overseas colonies. In particular, this study shows how, both in Italy and in its former colonies, the development of penal colonization was interrelated with the process of nation-building.

In the second section, I analyse the borders between convicts and free citizens, and between penal territory and free territory. In particular, I focus on the agricultural penal colony of Castiadas in Sardinia (Figure 1). Possessing vast territories to be reclaimed and exploited, Sardinia has acted as a kind of penitentiary region throughout Italian history. The agricultural penal colony of Castiadas was founded in 1875 and continued to function until 1956. Extending over 6,500 hectares, it was Italy's largest. By 1883, it was hosting 996 convicts as well as 1,200 “assigned” or “consigned” persons, those who worked there during the day but did not have restrictions imposed upon them.Footnote 4 As with other agricultural penal colonies, Castiadas included convicts who had already served part of their sentence in prison and were considered to be worthy of reward.Footnote 5 Like most of the penal colonies that were later founded in Italy, Castiadas was established in a malarial area. In many respects, it was a paradigm for penal colonization in Italy, and its economic and social model echoed the other agricultural penal colonies in Sardinia, the circulation of ideas, practices, convicts, and goods being a cornerstone of the island's history.Footnote 6 I pay particular attention to the social and economic conditions of both prisoners and free citizens, in order to highlight how the penal colony influenced their lives. The relationship between captives and citizens is also shown by records concerning the escape and capture of fugitives. In particular, these documents show the porous character of the penal colonies’ borders and the frequent crossing of boundaries between penal and free territories. In my analysis, these acts of escaping, which provided interactions with the surrounding territory, foreground the way in which internment policies extended the colony far beyond its own physical boundaries.

Figure 1. Sardinia, with the location of agricultural penal colonies.

RECLAIMING ITALY: AGRICULTURAL PENAL COLONIZATION IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES

At the turn of the twentieth century, discourse on the penal system in Italy was inevitably wrapped up with questions about the social system that the new nation state sought to promote. In particular, penitentiary colonization by way of internal colonies was considered an alternative to overseas transportation of Italian criminals. Plans for the creation of overseas penal colonies were interlinked with those for establishing the first bases of colonial expansion. In other words, the discussion dealt with the places where penal colonies were to be established and whether such places were to be located in Italy or overseas. One of the various sites considered for a penal colony was Assab in Eritrea. The Italian penetration of Eritrea began in Assab in 1869, thanks to the purchase of this coastal area by the Rubattino Company. It was here that the only overseas prison colony in Italian history was established, in 1899. The experiment was brief, as environmental and climatic conditions wiped out the detainees, and the decision was made later in the same year to shut the colony. Despite these environmental difficulties – which were already well known – the bay had been chosen as location for the new penitentiary site because any contact between the convicts and the local population was eliminated, thus safeguarding the “prestige of the [Italian] race”.Footnote 7

Italian colonial society was constantly driven by tensions surrounding the defence of racial prestige. These were principally derived from the presence of numerous poor whites among the Italian colonists, who, on account of their economic conditions (and occasionally their lifestyles), were dangerously close to the indigenous people whom the Italians were meant to be “civilising”.Footnote 8 In this context, the presence of Italian forced labourers constituted a further threat to the maintenance of the borders between the two communities. In 1891, the Royal Commission of Inquiry on Eritrea expressed itself along these lines, highlighting that penal colonization had discouraged the influx of “honest colonists and fathers of families” whom the administration favoured.Footnote 9 Most importantly, in contrast to British deportations to Australia, in the Italian case deportations did not make sense economically: there were plenty of Italians who were well disposed to moving to Eritrea, and the cost of their labour was probably much lower than that which the administration would have had to pay to establish and maintain penal colonies.Footnote 10

It would be much better, it was said, to employ Italian prisoners to reclaim the country's own portions of uncultivated and malarial land. As Matteotti wrote in The Times, “Italy must first of all reclaim itself”.Footnote 11 Jurists, civil servants, and scholars of the prison system considered agricultural work to be a privileged area for the development of penal labour. Both supporters and opponents of prison labour agreed that work in the fields was “undoubtedly a source of beneficial results”, in the first place because it did not pose any competition to free labour, a question of central importance in the discussion over prison labour.Footnote 12

Yet, penitentiary colonization should be seen within a wider context. All penal colony projects were considered to be at the vanguard of free colonization.Footnote 13 Supporters saw agriculture and the rural world as the basis of economic and social projects for the Italian proletariat. When Italy made the first steps to conquer a “place in the sun” of its own, providing land and work to the proletarian masses, the supporters of internal colonization exalted the advantages of free agricultural colonies as a remedy for the problem of emigration and, in general, for “practically resolving the grave problem of raising and comforting the proletariat, furthermore preventing any social crisis from emerging”.Footnote 14 In this view, internal colonization in particular would favour the countryside, making it more populated, countervailing the waves of migration towards the urban centres and promoting a particular social model: “The colonizers must distinguish themselves through their activity, frugality, tenacity, and honest conduct, and possess discrete capital.”Footnote 15

The agricultural penal colony was a tool of social engineering in the context of a wider project of national regeneration. From the perspective of reinserting criminals into society, agricultural labour was attributed the best results in terms of rehabilitating and re-educating prisoners, with man improving the land and land improving the man.Footnote 16 The agricultural colonies’ function was no less important as an instrument of social conservation since, according to prison statistics, at least half of all prisoners came from the rural world.Footnote 17

The daily life of those detained in the colonies was closely controlled by a host of rules that were aimed at fashioning the good farmer (see Figure 2). These regulations impacted on the bodies of detainees, including through norms of hygiene and nutrition, forging disciplined masses and efficient farmers.Footnote 18

Figure 2. A prisoner working in the Castiadas agricultural penal colony at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Agricultural penal colonies were also developing in other European metropoles, but with the aim of re-educating minors. In France, the Netherlands, and Belgium in particular, colonies were established for “delinquent” minors, with faith being placed in the “moral virtues” of agricultural labour, as was the case in Italy. A European perspective shows the peculiarity of the Italian case, above all owing to the absence of overseas transportation. In contrast, penal colonies were an integral part of the English, French, and Dutch imperial systems. The Italian case was different because the agricultural penal colony was part of a project of nation-building that was to take place through the colonization and valorization of the country's unproductive southern regions.Footnote 19

Discussion around the function of penal colonization was closely connected to discussions about the regeneration of southern Italy. The agricultural penal colonies were located “in deserted regions and on islands, far from trade centres, and which are insalubrious and unproductive on account of the lack of population and their long abandonment. In general, therefore, these are localities in which private speculation will never be able to take off”.Footnote 20 These localities were mainly situated in the south. Penitentiary policy enacted by the first Italian governments saw that five out of the eight penal colonies that were established in Italy were located in Sicily.Footnote 21

Colonies for domicilio coatto, or forced residence, were also founded in southern Italy, especially on the islands. Domicilio coatto was established after Italian unification as a public security measure: it was not, therefore, a sentence as such and those affected by it did not go through a normal trial. Its aim was the removal of subjects who were considered to be “dangerous” by the established order for political and/or social reasons, but who could not be handed over to judicial powers owing to a lack of evidence. While labour lay at the centre of the project of agricultural penal colonies, the majority of those who were under domicilio coatto did not have any form of employment.Footnote 22

At the turn of the twentieth century, the ruling classes pinpointed southern regions for the development of penal sites because of a combination of factors: the isolation of the chosen sites; colonization of parts of the country that were empty; and finally, a racialized vision of southern populations. As already highlighted by the literature, the policies implemented for the southern regions in the decades following Italian unification were also influenced by an “oriental” vision of southerners, sometimes considering them along the same lines as African subjects.Footnote 23 Angelelli and Cusmano, who were both agronomists in Castiadas, described the territory as wild, virgin, and lacking human presence, and for this reason in need of colonization. I should emphasize that they resorted to the same vocabulary that was adopted by colonial functionaries and scholars. As was the case in Sardinia, Western powers’ supposed right to colonize and “tame” overseas possessions derived from the idea that African and Asian territories were wild, virgin, and empty areas.

Around the end of the nineteenth century, Sardinia became the preferred site for the institution of penitentiary agricultural colonies.Footnote 24 There were geographical, agronomic, and demographic factors that contributed to this choice. Sardinia is an island, far from the rest of Italian territory, and this guaranteed the ideal conditions for prisoners’ isolation. Furthermore, of the one million hectares of Italian land to be reclaimed at the beginning of the twentieth century, a good 260,000 hectares of marshy terrain lay in the region. The remaining marshland was concentrated in the Po Valley (Piedmont, Lombardy, and Emilia Romagna) and along the coasts of southern Italy. Furthermore, with only 609,015 inhabitants, Sardinia was characterized by a particularly low demographic density in comparison not only with other southern regions (Sicily was host to 2,408,521), but also other regions with marshland in the north: Lombardy had 3,160,481 inhabitants, Emilia Romagna 2,100,055, and Piedmont 2,758,500. Thus, by 1906, there were already six agricultural penal colonies in Sardinia, employing around 2,000 prisoners.Footnote 25 With the rise of the Fascist regime, land reclamation became part of a vast programme of “regenerating” Italian society, in which recovering the land was only one tangible aspect of a project for the purification and reconstruction of an Italian mentality and the formation of a “new Fascist man”. Sardinia had remained outside the early political and social processes triggered by the regime, meaning that the island's land reclamation project was to have a double goal: to convert the Sardinian people to Fascism and, at the same time, to concede land for cultivation to farmhands and sharecroppers from other Italian regions, chosen from among those politically closest to the regime.Footnote 26

The island's land reclamation projects thus conjoined with those for internal colonization according to a model of Fascist rurality that foresaw the creation of new planned villages. The penitentiary agricultural colonies were therefore an integral part of the Fascist land reclamation project; their history connects with that of the public bodies for colonization that operated long after the fall of the Fascist regime and the end of World War II.

The idea of transportation re-emerged within the context of the Fascist programme for prisoner rehabilitation. In particular, in the 1930s, the Ministry of Justice and the Colonial Ministry studied plans for agricultural penal colonies in Libya for Italian prisoners. Work was a key part of this programme, which sought criminals’ regeneration as part of the construction of Fascist society. Unlike projects in earlier years, it was said that the government would truly take care of the rehabilitation of prisoners through agricultural labour. It was those with previous experience in agricultural labour who were to be sent to the penal colonies, not the “incorrigible”.Footnote 27 After first focusing on Libya, these projects were also promoted in eastern Africa. In 1932, at the height of the construction of the empire, the senior director of Rome's prison system, Tito Cicinelli, maintained that the new penal code had abandoned the old concept of “white man's prestige”.Footnote 28

In other words, fears of how the presence of Italian prisoners might diminish the colonizer's prestige in African eyes had now lessened. Seven years earlier, in 1925, Cicinelli had drawn an explicit parallel between Italian southern regions and African territories. He had expressed his support for the use of Italian prisoners to improve Somali lands conceded by Great Britain (so-called Jubaland), making an interesting reference to penal colonization in Sardinia:

[W]hat impression do you want it to make on the Somali's primitive psyche – he who up till yesterday worked in slavery in the most barbarous fashion – when he sees a few thousand whites, guilty of having failed their duties as citizens in the Fatherland, sent to work on the banks of the Juba as punishment, in conditions that – for we who have some experience of our Sardinian penal colonies – would differ very little from those of the free labourer?

Most importantly, Africa and Sardinia were united by the fact that both were lands of “redemption”. Cicinelli continued: “the functionaries of the prison administration must sacrifice themselves for the Fatherland in Africa, just as they are already doing as they serve in the malaria-ridden lands of Sardinia”.Footnote 29

The plans for agricultural penal colonies in Africa for Italian prisoners were not put into effect, primarily because of the military and financial difficulties of the Italian colonial enterprise. Nevertheless, it is worth noting the connection between Africa and Sardinia that these plans established. In short, within the context of penal labour, the boundaries between the colonized and the colonizers, and thus between motherland and colony, faded considerably.

THE PENAL COLONIES’ TRANSIENT BORDER

As previously noted, in Italy, the penal colony was considered to be a means of reclaiming land, above all in the south.Footnote 30 In the perceptions and discourse of a good part of Italy's business and political elite, the south was a “colonial” territory, a virgin and wild land to be redeemed and then conquered. “What is Castiadas?”, a penal colony functionary asked in 1883:

[It is a] locality that has always been left to itself, with its earth never broken by the farmer's iron. Only in winter do you see some tanned shepherd […] who, even wilder than the locality itself, on returning to his own region in summer leaves behind him such a whirling, destructive fire that immense, centuries-old, extremely thick woodlands are reduced to ash.

Penal colonization was a civilizing undertaking that had brought the territory into a new era; the “roving, wild, idle shepherding is replaced with profound, intensive, social labour; abandonment is replaced with life, and ignorance with science”.Footnote 31 As with the colonial possessions overseas, colonizing projects in southern Italy were also based on the idea of redeeming the land in order to redeem man, following the notion of a civilizing mission realized by way of agricultural labour.

The archival records on Castiadas testify how the process of regeneration of the land blurred the boundaries between free workers and convicts. In 1863, twelve years before the penal colony in Castiadas was established, some farmers moved there in order to colonize the area. Therefore, the project for the colonization of Castiadas's salto (i.e. land for the collective use of local communities) was undertaken by free colonists and well before the prison administration's plans for this part of Sardinia came to fruition.Footnote 32 In 1895, twenty years after its establishment, as many as 200 free people, both men and women, were living within the penal colony. This included the guards, farmers, administrative staff, and the director, as well as their respective families. Castiadas was a kind of site of redemption even for the colony's staff. The situation was particularly harsh for the prison guards, whose discontent became clear from the outset. In the first phase, Martino Beltrani Scalia, head of the Prison Department for the Ministry of the Interior, considered only recruiting officers from Sardinia itself, but this proposal was not carried through. In 1884, compensation was established for all staff in the agricultural penal colonies, in which the employees of the Castiadas colony were awarded the highest sums available, because it was classified as a particularly inhospitable location.Footnote 33

Generally, the living conditions and health of convicts and free people differed only negligibly. Prisoners and civilians alike were plagued by malaria and, certainly, up to the early 1900s, this claimed a large number of victims, foremost among the imprisoned, but also among the guards and other employees, albeit to a lesser degree.Footnote 34 Living conditions for civil servants working in Castiadas were undoubtedly harder than those of employees at other penal institutions. In 1888, the director complained that the accommodation for civil servants in Castiadas was extremely small and unhealthy. In the same year, the post office employee lived together with his family in a single room that made up part of the management offices.Footnote 35

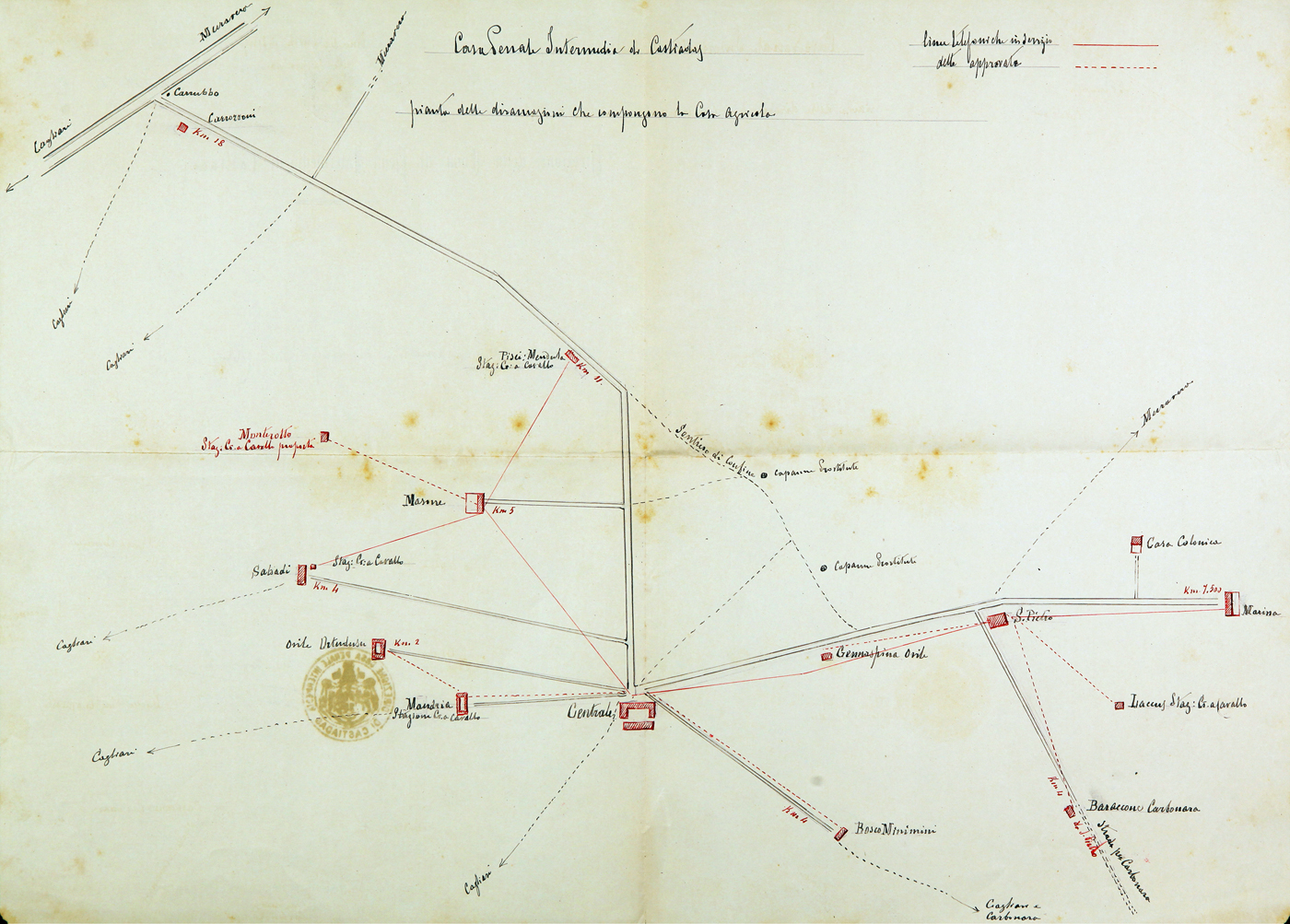

However, convicts had the heaviest burdens, such as building the first facilities and reclaiming and ploughing the land. Their working day and diet were arranged in order to reach maximum productivity. The colony was organized into diramazioni, surrounding satellite sub-colonies or production units supplied with all the tools and infrastructure necessary for detainees’ labour and survival. The 1902 map of the colony shows all these outer branches and how far each of them stood from the central site, with the furthest outlier located some eighteen kilometres away (see Figure 3).Footnote 36 The division of the colony into branches corresponded to a dual goal: on the one hand, to organize the labour necessary for tilling the land and agricultural production in the most rational way possible; on the other, to provide the nuclei of future free colonies that would eventually be established in the area. Once the colony's land had entirely been ceded to the free colonies, the penal establishment's central hub would become the area's administrative centre.Footnote 37 This was not only the plan for the Castiadas colony, but also for other penal colonies in Sardinia. According to some prison administration functionaries, free colonization was to avail itself of penal labour even after the phase in which the land had been reclaimed and tilled.Footnote 38

Figure 3. Map of the Castiadas colony in 1902.

However, forced labourers could themselves become free colonists after finishing their sentences, becoming owners of small portions of land in the same area that had previously belonged to the penal colony. For the most part, these projects only existed on paper but they do have a certain value, above all for understanding how the penal colony and the forced labourers were seen. In this sense, I think that we can say that forced labourers and colonists both belonged to a single socio-economic project for reclaiming a given territory, one that also included an idea of human reclamation and national regeneration.

The penal colony certainly represented a significant source of income for the majority of the population living in Castiadas and thereabouts. More generally, the population of the surrounding area contributed to the penal colony by selling goods and services. Other relations animated its everyday life. In Castiadas, the administration lamented the presence of “idlers, vagabonds”, and prostitutes in search of small earnings and who, among other matters, sold the prisoners information that would help them escape.Footnote 39

Security in Castiadas was one of the crucial problems for its management. On May 1885, the director informed the prefect in Cagliari of a mutiny that had occurred at the colony. There was a particularly high number of prisoners at that time: in 1883, two years earlier, there had been 996 detainees.Footnote 40 The extremely hard living conditions during the summer season, owing to very high temperatures and the increasing spread of malaria, were the main reason behind the uprising. In 1890, Berardi, an employee at the prison, wrote that the history of Castiadas was a history of “suffering, sacrifice and heroism” on account of the “slaughter caused by pernicious fevers and the revolts mounted by the prisoners, who threatened to escape en masse”.Footnote 41 In order to tame the rioters, the authorities resorted to strict disciplinary measures. Fifty-six ringleaders were gathered in two rooms and bound with “chains, each one made up of eighteen links”.Footnote 42 All the other convicts were sent to work. According to the director, it was thought that improvement in the quality of the food provided to the prisoners might help to relieve their unrest. The prefect maintained that the convicts in Castiadas were “very demanding for food”, because they were aware that with better nourishment they could be healthier and more resistant to malaria.Footnote 43 Most likely, a good diet for the convicts also concerned the penal colony's leadership in terms of its relevance to the prisoners’ productivity. On the other hand, the authorities tried to meet the requirements of the detainees in order to avoid further unrest, as the majority of the convicts were “consigned persons” in the area. According to the prefect, an equilibrium needed to be maintained in Castiadas for two main reasons: on the one hand, unrest “caused damage to the [economic] trend of the colony”, which was the main concern of the managing group; and on the other hand, since most of the detainees were free to move within the colony's area, they were potentially more dangerous in terms of security than detainees who were contained inside a prison with well-defined boundaries.Footnote 44

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Cusmano, one of the penal colony's agronomists, maintained that Castiadas, surrounded by woods, was characterized by natural borders that made it difficult to guard, in terms both of those entering the colony and those leaving it.Footnote 45 The history of escapes clearly demonstrates the administration's difficulties in maintaining control over a woodland territory where it was easy to leave no tracks. The various directors entrusted with the colony, conscious that they could not access the men and resources needed to maintain effective control over the area, had to rely on other tools instead.

Primarily, highly restrictive and hierarchical prison norms and practices demanded that one of the guards be identified as responsible each time an escape was made. The guard in question would then be referred to the judicial authorities and risked losing his job or even ending up in prison himself. Without doubt, the most effective tool, however, was to enlist the help of the local population across a vast area, this including all the villages surrounding the colony and stretching as far as the city of Cagliari. With a system based on generous rewards (comparable to that for collaborators in Libya and Italian East Africa), the administration managed to secure effective control over the territory using an unspecified number of people. The escape of prisoners from Castiadas between 1893 and 1915 almost always ended in reports or even “arrests” carried out by private citizens.Footnote 46 As the prefect of the Cagliari police wrote to the Ministry of the Interior in 1898 in relation to two prisoners who had escaped, “The fugitives will certainly be caught immediately, because they will find no support from the Sardinian peasant; rather, sure of the gratification that the government has always wisely given him in similar infelicitous cases, [the peasant] will cooperate with the force's agents in the arrest of the escapee prisoner”.Footnote 47 Between 1893 and 1915, twenty-five prisoners attempted to escape from the penal colony but only six managed to do so, while the other nineteen were arrested thanks to the collaboration of the local borghesi.Footnote 48 This participation of the borghesi,Footnote 49 in controlling the detainees, allows us to identify a large “carceralized” territory that extended far beyond the penal colony itself. An analysis of evasion shows the mobility of the borders between the colony's territory and the free territory. Looking at all the relations between the penal establishment and the local population, we can say both that the colony extended into the surrounding territory and that the latter entered into the colony.

Nevertheless, the relationship between the Sardinian population living in the area surrounding the colony and the prison administration was not only characterized by collaboration, but also by resistance. Clearly, the dualism collaboration/resistance resonates with the typical colonial relationship between colonizers and colonized. The primary reason for the disputes between the prison administration and the municipalities in the immediate surroundings of Castiadas concerned rights to use the land in the area of the penal colony. The colony's establishment in 1875 had deprived the local community of a vast territory, which had been utilized in particular by the shepherds for pasture, for seasonal herding, and for wild grazing in surrounding areas. In 1892, the director of the penal colony requested the faster prosecution of shepherds who “invaded and devastated” the farms of Castiadas.Footnote 50 In 1929, the Cassa provinciale di credito agrario, a local bank, claimed its rights over the area housing the Sardinian penal colonies of Isili, Castiadas, and Mamone.Footnote 51 This dispute was only concluded in the 1930s, when the Fascist regime marked a turning point in the agricultural colonization of Sardinia. In 1933, the government established a public body,Footnote 52 the Ente ferrarese di colonizzazione, in order to employ workers from the north Italian town of Ferrara in the colonization of Sardinia. For this purpose, the Ministry of Justice transferred the land from the penal colonies of Castiadas, Isili, and Cuguttu to the Ente.Footnote 53 Yet, the Ministry of Justice continued to manage the penal colonies, and prisoners continued working for the agricultural development of these territories.Footnote 54

In fact, by the 1930s, most of the plots of land within the colony's borders had still not been cultivated. Generally, in terms of goals achieved, the penitentiary colonization seemed mediocre in Castiadas, as well as in most of the other Italian penal colonies. The economic output of these farms was far below expectations.Footnote 55 Certainly, the sacrifice of the detainees in Castiadas contributed to reclaiming the area from malaria, at least partly, but at the cost of many human lives. Ideological assumptions about and economic considerations of the penal agricultural colonies went hand in hand over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, penal colonization tended to act primarily on an ideological rather than on an economic level.

CONCLUSION

After World War II, significant parts of the colony were sold to the Ente ferrarese, later replaced by Ente Trasformazione Fondiaria Agricola Sarda (ETFAS), the Sardinian public body for colonization. Simultaneously, a large number of prisoners were transferred to other penal institutes. In 1956, those who remained at the penitentiary in Castiadas were consigned to ETFAS, leading to the final decommissioning of the agricultural penal colony. The new public body organized the fragmentation of the fund and the establishment of a range of agricultural companies. The new “colonists” were not former prisoners from the penal colony but local residents, working in conditions not dissimilar from those of the first prisoners who arrived at the end of the nineteenth century.

In 1953, Fiorenzo Serra made a documentary about Castiadas entitled Assault on the Scrub. The penal colony was closed shortly afterwards. It is worth noting that Serra described Castiadas in virtually the same terms as Angelelli and Cusmano: “As with many other areas in Sardinia, this one also gives the immediate sense of the state of abandon.” Wild nature dominated Castiadas and there was no trace of the improvements that according to the former employees of the penal colony were achieved in the area, in particular in terms of the colonization and “redemption” of the land.Footnote 56

As Carlos Petit highlights, the history of the penal colonies points out the centrality of four main features: the idea of protection/education of the penal population; the relationship with nature as a source of education for the prisoners; labour as a fundamental tool both to regenerate and to redeem; and, finally, family as the context that includes all the other features, a tool for the re-education of the detainee and the goal of his reform project.Footnote 57

Observing the borders of the penal colony clearly shows the socio-economic project that was the foundation for penitentiary colonization. The continual crossing of borders between free and penal territories, between prisoners and free workers, and between the colonizers and the colonized that emerges from the analysis of Castiadas brings into question the concept of the penal colony itself, as a site separate and/or closed off from the surrounding territory. In Italy, and possibly also elsewhere, the penal colony was designed not only to discipline convicts, but also the population of the surrounding territory. Its economic and social organization was the development model for rural areas in Italy from unification down to the first decades of the twentieth century. In particular, the agricultural penal colony was conceived as a tool of social engineering in the construction of Italy as a nation, and, even if with different declinations, from Italian unification onwards, both in the Liberal period and under Fascism.