Introduction

Structural priming refers to the phenomenon whereby language users’ production or processing of a linguistic structure is facilitated following their encounter with a similar linguistic structure (Arai et al., Reference Arai, van Gompel and Scheepers2007; Bock, Reference Bock1986). For instance, upon hearing a prepositional (PO) dative sentence, such as Mary gave a cake to David, a language user is more likely to produce or expect to encounter another PO dative, such as John sent books to Lily, in a subsequent utterance than its double object (DO) dative alternative John sent Lily books.

Structural priming effects have been considered a reflection of implicit language learning through predictive processing (e.g., Branigan & Messenger, Reference Branigan and Messenger2016; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Dell and Bock2006; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019): Language users predict upcoming words during processing. Thus they may initially predict a structure that will prove to be different from the actual structure encountered, giving rise to prediction error, which in turn drives language users to adapt their knowledge base and shift their prediction/production next time, to align their subsequent predictions/productions more closely with the input and avoid future prediction errors (e.g., Jaeger & Snider, Reference Jaeger and Snider2013). Over time, this adaptation can result in sustained changes to their linguistic representations, that is, learning.

Young adult native speakers are found to engage in prediction in many, though not necessarily all, processing situations (for recent reviews, see Huettig & Mani, Reference Huettig and Mani2016; Pickering & Gambi, Reference Pickering and Gambi2018). In contrast, second language (L2) learners tend to show reduced, delayed, or even no effects of active prediction during online processing (for a recent review, see Kaan & Grüter, Reference Kaan, Grüter, Kaan and Grüter2021). If prediction is a prerequisite for learning, L2 learners may have less opportunity to learn from prediction errors (Hopp, Reference Hopp, Kaan and Grüter2021). Studies on the connection between L2 prediction and learning are thus crucial for a better understanding of the processes and outcomes of L2 acquisition. Yet it is only very recently that the potential links between (reduced or different) prediction in L2 and L2 learning have become an object of interest and investigation in the Second Language Acquisition (SLA) field (e.g., Coumel et al., Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2023; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Zhu, Jackson, Kaan and Grüter2021; Jackson & Hopp, Reference Jackson and Hopp2020; Kaan & Chun, Reference Kaan and Chun2018; see Bovolenta & Marsden, Reference Bovolenta and Marsden2021; Hopp, Reference Hopp, Kaan and Grüter2021, for recent reviews).

The dative alternation refers to the phenomenon that some, but not all, verbs can alternate between different ditransitive/dative constructions in languages with more than one, such as English and Mandarin. It has been proposed that error-driven learning (EDL) mechanisms underlie the acquisition of the dative alternation (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Janciauskas and Fitz2012; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019). Through experiencing prediction errors and adjusting language representations accordingly, learners can acquire the biases associated with individual verbs to appear in one or another dative construction. The research on the acquisition of the dative alternation via EDL has focused on first language (L1) English child and adult speakers (e.g., Fazekas et al., Reference Fazekas, Jessop, Pine and Rowland2020; Jaeger & Snider, Reference Jaeger and Snider2013; Peter et al., Reference Peter, Chang, Pine, Blything and Rowland2015). Recently, a handful of studies have begun to extend this inquiry to L2 English learners (e.g., Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Zhu, Jackson, Kaan and Grüter2021; Kaan & Chun, Reference Kaan and Chun2018; Tachihara & Goldberg, Reference Tachihara and Goldberg2020), whereas the dative alternation in the learning of languages other than English remains understudied.

To contribute to the research on the connection between L2 prediction and learning and to extend this line of research beyond European languages, the present study investigates whether structural priming can facilitate L2 learning of the Mandarin dative alternation. Using a written structural priming paradigm together with acceptability judgment tasks (AJTs) pre- and post-priming, we ask whether the effects of L2 learning, if any, manifest in both production and acceptability judgments.

Structural priming effects and language learning

Structural priming can manifest as an increased likelihood of producing the primed construction immediately following the prime sentence(s), which is traditionally called the short-term priming effect (e.g., Jackson, Reference Jackson2018). Structural priming has also been observed when the prime and target sentences are not adjacent, which are called long-term priming effects. Long-term priming effects have been witnessed when the prime and target sentences are separated by multiple intervening sentences (Bock & Griffin, Reference Bock and Griffin2000), or in posttests conducted a day or even a few weeks after the priming session (e.g., Branigan & Messenger, Reference Branigan and Messenger2016; Heyselaar & Segaert, Reference Heyselaar and Segaert2022, for L1; Kim & McDonough, Reference Kim and McDonough2016; McDonough & Chaikitmongkol, Reference McDonough and Chaikitmongkol2010, for L2). Long-term priming effects provide support for the claim that structural priming effects are products of implicit learning.

Despite its robust presence among native speakers, long-term priming effects sometimes are absent or reduced among L2 learners (e.g., Jackson & Hopp, Reference Jackson and Hopp2020; Jackson & Ruf, Reference Jackson and Ruf2017; McDonough, Reference McDonough2006). Jackson & Hopp (Reference Jackson and Hopp2020) found that German L2 learners of English showed stronger short-term priming effects than native speakers in their production of fronted adverbial phrases (e.g., In the morning the grandfather drinks hot chocolate). However, these short-term priming effects in the L2ers failed to translate into longer-term priming effects in a posttest immediately after the priming phase, unlike what was observed for the L1ers. Jackson & Hopp (Reference Jackson and Hopp2020) thus suggested that prediction error may not necessarily feed into L2 learning. On the other hand, Coumel et al. (Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2023) observed long-term priming effects both in an immediate posttest after priming and in a 1-week delayed posttest among French-speaking L2 learners of English regarding their production of English passives. Similarly, Grüter et al. (Reference Grüter, Zhu, Jackson, Kaan and Grüter2021) also observed longer-term priming effects in an immediate posttest after priming Korean-speaking L2 English learners with DO sentences. Intriguingly, the longer-term priming effects were greater among participants in the Guessing-Game (GG) condition, where they guessed a virtual partner Jessica’s description of pictures and then compared their guess with the actual sentence Jessica had produced (the primes), than among those in the control condition, who read and retyped Jessica’s descriptions in the primes. One explanation for the greater priming effects in the GG group was that this treatment encouraged L2ers’ prediction and attention to prediction errors, and therefore facilitated learning.

Structural priming effects tend to be larger when less frequent/expected items are primed, known as the inverse frequency effect (e.g., Kaschak et al., Reference Kaschak, Kutta and Jones2011). The inverse frequency effect can be well explained through the EDL accounts, which predict that the size of learning is proportional to the size of the prediction error: Less frequent/expected items bring out larger errors of prediction, leading to larger adjustments of learners’ linguistic representations, hence larger priming effects. Previous research on L1 child and adult speakers has shown extensive evidence of inverse frequency effects, consistent with EDL accounts (e.g., Bernolet & Hartsuiker, Reference Bernolet and Hartsuiker2010; Fazekas et al., Reference Fazekas, Jessop, Pine and Rowland2020; Jaeger & Snider, Reference Jaeger and Snider2013; Peter et al., Reference Peter, Chang, Pine, Blything and Rowland2015). Kaan & Chun (Reference Kaan and Chun2018) primed Korean L2 learners of English with DO and PO datives and observed an inverse frequency effect in cumulative adaptation, that is, the magnitude of priming increased with an increasing number of target structures encountered, and the effect size was larger for DO, the dative that was initially dispreferred among L2 learners. However, despite the cumulative adaptation, there were no immediate priming effects among L2 learners in this study, that is, they did not produce significantly more DO or PO sentences in the prime trials than in baseline trials.

As discussed above, studies on L2 learning from structural priming have been limited in number and mixed in results. More research is needed to determine whether L2 learners can benefit from implicit error-driven learning, and under what circumstances they are more likely to do so. In addition, L2 structural priming studies have almost exclusively relied on increased production of the primed construction(s) as the critical measure of “learning,” following the L1 literature on structural priming and implicit learning. Meanwhile, another common source of evidence for acquisition in SLA has come from acceptability judgments (Plonsky et al., Reference Plonsky, Marsden, Crowther, Gass and Spinner2020), a measurement to examine individuals’ judgments of what is and what is not acceptable in a given language, and thus used to infer what is and what is not allowed in individuals’ linguistic representations (Spinner & Gass, Reference Spinner and Gass2019). If structural priming effects result from updated linguistic representations, we may reasonably infer that these updated linguistic representations can also lead to changes in learners’ acceptability judgments for the primed construction(s). Therefore, it is intriguing to explore whether learning effects from structural priming can manifest in other measurements of learning, such as acceptability judgments. For instance, compared to native speakers, L2 learners of Mandarin are found to rate acceptable verb-dative pairings significantly lower and unacceptable pairings significantly higher (He, Reference He2013; Zhu & Zhao, Reference Zhu and Zhao2016), which enables us to examine in this study whether L2 learners will supply more native-like acceptability ratings after priming.

The dative alternation in Mandarin

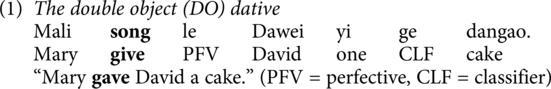

Mandarin is argued to have three dative constructions (Liu, Reference Liu2006). To simplify the research design, this study focuses on the alternation between two of them—the double object (DO) dative and the GEI-object (GO) dative, as shown in (1) and (2).

In Mandarin, DO is the most restricted dative construction in which the least number of verbs can occur. The GO construction, on the other hand, is the most lenient in that it disallows only one semantic class of dative verbs—verbs of communication (e.g., tell). Note that there is controversy regarding whether the GO construction is a prepositional (PO) dative (e.g., Soh, Reference Soh2005; Yang, Reference Yang1991) or a serial verb construction (SVC, e.g., Huang & Ahrens, Reference Huang and Ahrens1999; Lin & Huang, Reference Lin and Huang2015). Her (Reference Her2006) suggested that GO construction can be a PO or SVC depending on the property of the verb in it. Nonetheless, L2 learners’ perceptions might deviate from linguists’ analyses. L2 learners learn gei both as a verb and a preposition in Chinese classes (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yao, Bi, Ge and Shi2021), thus the (potentially varying) lexical category of gei in GO constructions is likely not obvious to them and they may consider GO as a single construction regardless of the nature of the verb in it. In this study, we follow Liu (Reference Liu2006) and use “GO” to refer to this construction; whether GO is a PO or SVC is not directly relevant to the research questions addressed by this experiment.

Pinker (Reference Pinker1989) observed that verbs of similar meanings behave similarly in terms of dative alternation in English. Accordingly, he proposed that the dative alternation is acquired through learning semantics-based rules: learners first form semantic verb classes in which members behave consistently, then generalize newly encountered verbs to the well-formed distinct semantic classes. Linguists suggested that the semantics-based rules for the dative alternation also apply in Mandarin (e.g., Liu, Reference Liu2006; Zhang, Reference Zhang1999; Zhu, Reference Zhu1979). In this study, we used three semantic classes of verbs: (1) verbs of giving, or GIVE verbs, which can alternate between DO and GO; (2) verbs of creation, or MAKE verbs, which can only occur in GO, and (3) verbs of communication, or TELL verbs, which can only occur in DO.

Little is known about the L1 and L2 acquisition of the dative alternation in Mandarin due to a lack of experimental studies. The only two studies to our knowledge on L2 acquisition (He, Reference He2013; Zhu & Zhao, Reference Zhu and Zhao2016) found that L2 learners did not possess native-like knowledge of the dative alternation even after years of learning: They produced unacceptable verb-dative pairings and rated those unacceptable pairings significantly higher than native Mandarin speakers did. More acquisition studies using different methods are needed to corroborate these observations of learning outcomes and to probe the learning mechanisms underlying them.

Error-driven learning of the dative alternation

Error-driven learning (EDL) approaches, such as the Dual-path Model of Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Dell and Bock2006) and the statistical preemption account by Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019), suggest that it is prediction error, that is, the difference between learners’ predicted sentences and the actual input they encounter, that leads to learning, such as the learning of the dative alternation in English. Studies on the learning processes of the dative alternation in other languages, such as Mandarin, are needed to examine the generalizability of these proposed mechanisms.

In recent studies on the connection between prediction error and learning, structural priming paradigms are often used to create a language environment where language users might learn and predict based on the statistics of the primed sentences. The present study uses structural priming combined with acceptability judgments to probe the underlying mechanisms that support the learning of the dative alternation in Mandarin. Consistent with the mechanisms proposed by Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Dell and Bock2006), we predict the following: In a prime trial, an English-speaking L2 learner of Mandarin may be influenced by their L1 and expect the verb zuo (“to make a meal/cup/etc. for someone.”) to occur in the DO construction (which is not acceptable in Mandarin), analogous to the acceptable use of its translation equivalent in DO constructions in English (e.g., “She made her friend a delicious meal”), yet they will see it in the GO construction. Thus, this learner encounters a prediction error. This prediction error will strengthen the connection between the verb zuo and the GO construction in their mental representations. This change in the learner’s linguistic representations will be reflected in a higher probability of producing the zuo-GO pairings, and higher acceptability ratings for the zuo-GO pairings after priming.

Statistical preemption refers to a phenomenon whereby language learners gradually realize that a certain form or construction is unacceptable if it could reasonably have been expected to occur; however, a competing alternative is repeatedly encountered instead (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019). In the scenario outlined above, if a learner of Mandarin repeatedly predicts zuo to occur in a DO construction, yet consistently encounters its competing alternative, that is, the zuo-GO pairing, instead during the experiment, the resulting prediction error can also serve as evidence that the zuo-DO pairing is not appropriate (at least in the current context). In that case, we could also expect the learner to produce fewer zuo-DO pairings and rate them lower after than before priming.

The present study

Research questions and hypotheses

This study addresses whether structural priming can facilitate the L2 learning of the dative alternation in Mandarin, as reflected in participants’ performance in both production (RQ1) and acceptability judgments (RQ2):

-

• Will participants increase the production of acceptable verb-dative pairings and decrease the production of unacceptable ones due to priming? (RQ1)

-

• Will participants increase acceptability ratings for acceptable and decrease ratings for unacceptable verb-dative pairings due to priming? (RQ2)

Based on EDL accounts and previous structural priming studies, we hypothesize for RQ1 that participants will increase the production of acceptable verb-dative pairings and decrease the production of unacceptable ones after priming. For RQ2, we hypothesize that participants will increase acceptability ratings for acceptable and decrease the ratings for unacceptable pairings after priming.

Participants

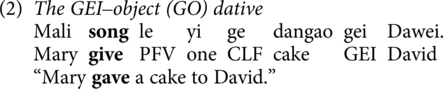

Twenty-five native speakers (L1ers) and 41 classroom learners (CLs) of Mandarin participated in this study. L1ers were included for two purposes: (1) to provide a basis for comparison of a distribution of responses towards which CLs may change as a result of priming, and (2) to examine whether learning effects also manifest among L1ers, as shown in the literature on structural priming in L1 (e.g., Jaeger & Snider, Reference Jaeger and Snider2013). The L1ers were international students or visiting scholars from China at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UHM). Most CLs (n=34) were current or previous students learning Chinese at UHM, 2 were students in Chinese classes at other universities, and 5 were recent high school graduates from the Honolulu community. All CLs had been learning Mandarin for over 1.5 years or were approaching the end of their third semester of Mandarin learning at a university in the United States, so they could be assumed to be familiar with the verbs used in this study. Participants received a $25 gift card or class credit as compensation.

The 41 CLs consisted of 23 sequential L2 learners (L2ers) who started to learn Mandarin in classroom settings from the ages of 9 to 45, and 18 English-dominant heritage learners (HLs) who had some exposure to Chinese in their childhood homes. Among the L2ers, there were a native speaker of French and Korean; the rest were native English speakers. Of the HLs, 11 were exposed to Mandarin during childhood, 4 to Cantonese, 1 to Hokkien, 1 to Taishanese, and 1 to Taiwanese and Mandarin. The L2ers and HLs were grouped together as they were recruited from the same classes (or communities). Two sample t-tests showed that they were comparable in age, scores on the Chinese LexTALE Test (LexTALE_CH, a character-based lexical test for proficiency, Chan & Chang, Reference Chan, Chang, Bertolini and Kaplan2018), self-rated overall proficiency, and length of stay in a Mandarin-speaking environment. See Table S1 in supplementary materials for more information about the L2ers and HLs. Table 1 presents the demographics of the L1ers and CLs. They differed in LexTALE_CH scores, t(63.99) = 10.708, p<.001, and self-rated proficiency, t(64) = 11.633, p<.001, but were comparable in age, t(64) = –0.049, p=.96.

Table 1. Participant demographics (means, standard deviations, and ranges)

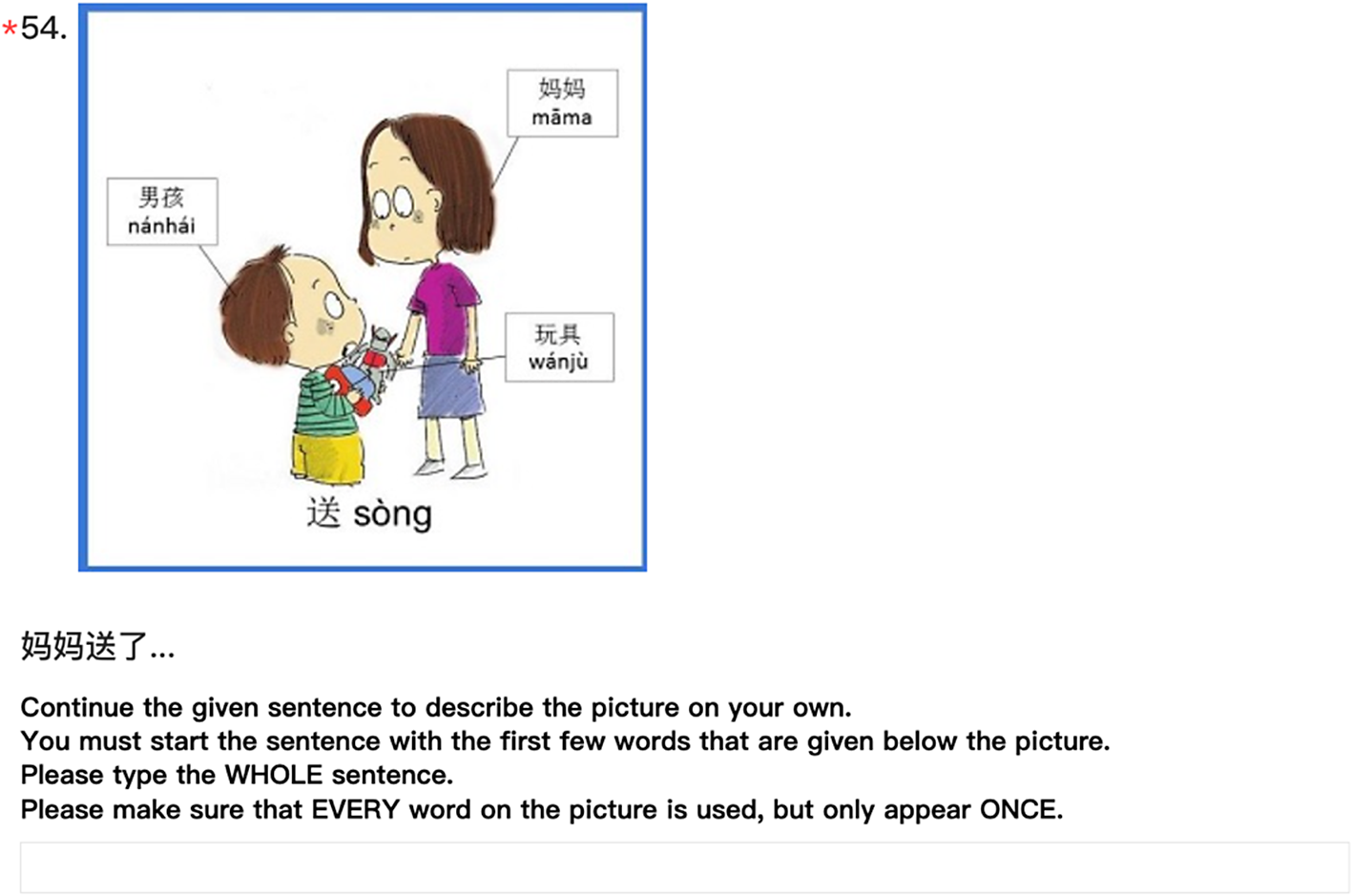

Materials

This experiment focused on the Mandarin DO and GO constructions (see example sentences [1] and [2] above) and their interaction with verbs of three semantic classes: Giving (GIVE) verbs that can alternate between DO and GO; creation (MAKE) verbs that can only appear in GO; and communication (TELL) verbs that are DO-only. Three verbs from each semantic class were chosen from Integrated Chinese (4th Edition), a popular set of textbooks in the U.S. (Ye, Reference Ye2019), to ensure that learners in this study were familiar with them (see Table 3 below).

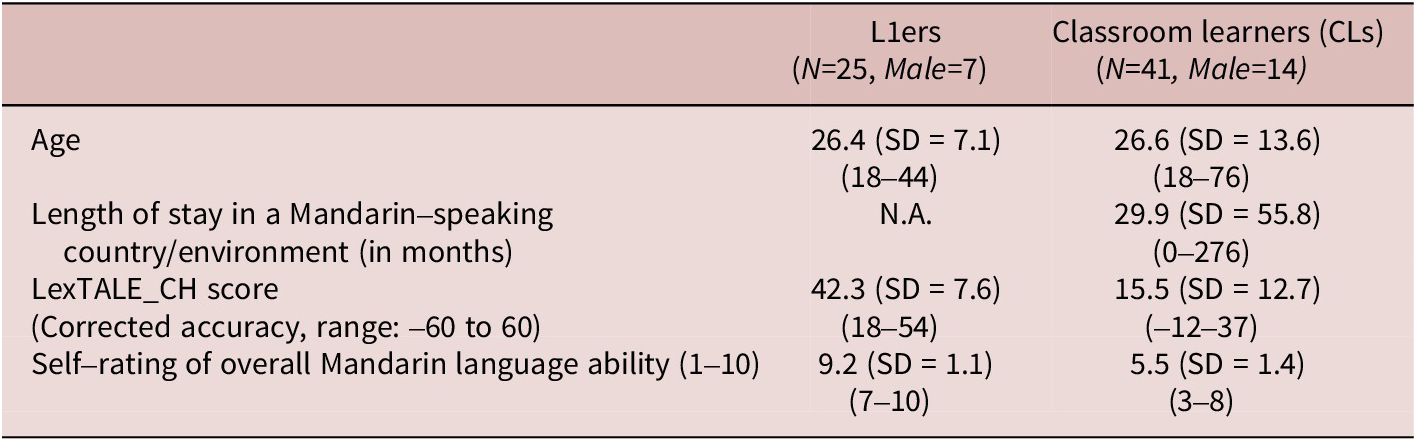

Design and procedure

The experiment implemented a pretest-treatment-posttest design (Figure 1). An acceptability judgment task (AJT) served as a pretest to probe participants’ initial knowledge of the Mandarin dative alternation. During the priming phase (B2, Figure 1), participants were exposed to acceptable verb-dative pairings only. We compared their production (B1 vs. B3) and acceptability judgments (A vs. C) before and after priming to seek evidence for learning.

Figure 1. Overview of the procedure.

Participants completed five tasks distributed over two days on an online survey platform (Wenjuanxing: https://www.wjx.cn/). Completion of all tasks took a total of approximately 60–90 minutes. On day one, participants completed two tasks: (1) a language background questionnaire, and (2) an AJT (pretest). On day two, they completed three tasks in this order: (1) a written picture description task (the structural priming session), (2) an AJT (posttest), and (3) the LexTALE_CH (Chan & Chang, Reference Chan, Chang, Bertolini and Kaplan2018) in which participants judged whether the given characters were real Chinese characters or not. The task consisted of 60 real characters and 30 nonce items and was scored for Corrected Accuracy (= number of correct hits −2 * number of false alarms; score range −60 to 60), as recommended by Chan & Chang (Reference Chan, Chang, Bertolini and Kaplan2018).

The written picture description (structural priming) task

The structural priming session was presented as a picture description task consisting of three phases (Table 2). There were two versions of the priming task with the same items in different pseudorandomized orders within each task phase (baseline, priming, post-priming). All linguistic stimuli, data files, and analysis scripts are available on Open Science Framework (OSF, https://osf.io/v9ej3/).

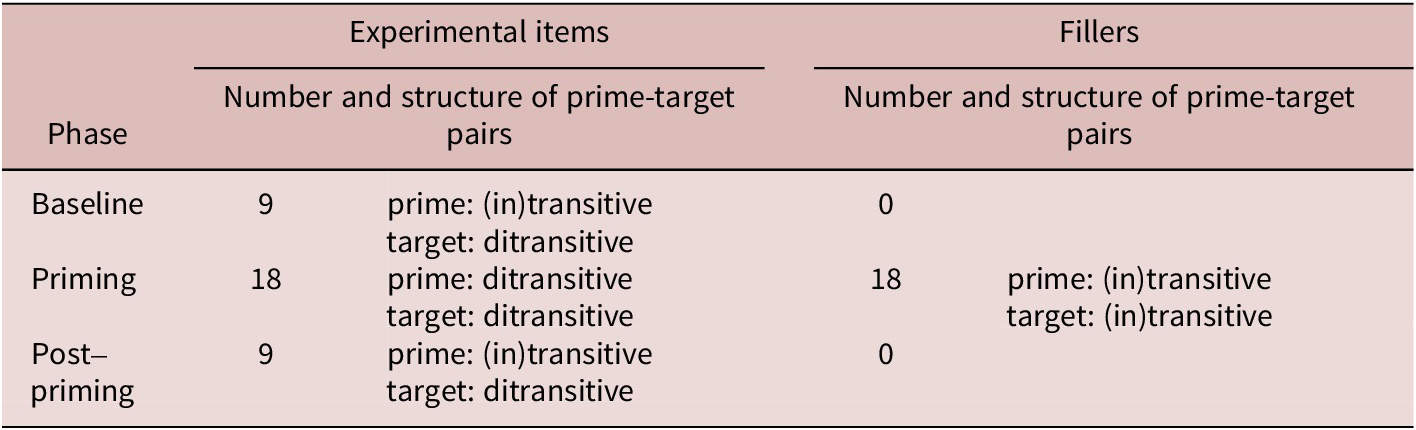

Table 2. Priming experiment: structure and materials

The boundaries of the 3 phases were unknown to the participants, to whom the task was presented as a continuous picture description task. Two practice trials were included before the baseline phase.

The baseline phase consisted of 9 prime-target pairs. Nine intransitive or transitive sentences were presented in the prime trials, while 9 experimental verbs from 3 semantic classes (Table 3) were used in the target trials to probe participants’ initial choices of ditransitive constructions when not primed.

Table 3. Experimental verbs in the structural priming session

In the priming phase, 2 experimental verbs from each of the 3 semantic classes were utilized, with each verb appearing 3 times as prime and target, resulting in 18 experimental prime-target pairs. The same verb did not repeat in a prime-target pair. For MAKE verbs, only GO constructions were primed. For TELL verbs, only DO constructions were primed. For GIVE verbs, the verb song (“to give”) was primed twice in DO and once in GO as it was suggested to be DO-biased (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang and Hartsuiker2022), and the verb jie (“to borrow/lend”) was primed twice in GO and once in DO, consistent with its suggested GO-bias (Chen et al.). There were also 18 filler prime-target pairs consisting of intransitive and transitive sentences.

The setting of the post-priming phase was the same as that of the baseline phase. For the priming effect, we measured whether the primed verb-dative pairings were more likely to be produced in the post-priming phase compared to the baseline phase.

In addition to the 6 experimental verbs included in the priming phase, another 3 experimental verbs (one from each semantic class) were included in both the baseline and post-priming phases (Table 3) as an exploratory measure to probe whether learners would limit their potential gained sensitivity to the primed verbs only, or they would generalize it to other verbs of the same semantic class, as suggested by Pinker’s semantics-based rule learning approach.

The structural priming task adopted the GG paradigm from Grüter et al. (Reference Grüter, Zhu, Jackson, Kaan and Grüter2021, described above) since it had elicited enhanced priming effects than more standard repetition priming. As L2 learners have been claimed to have reduced expectations during sentence processing and thus less opportunity for learning from prediction errors (Kaan & Grüter, Reference Kaan, Grüter, Kaan and Grüter2021, for review), we used the GG paradigm here to encourage prediction and computation of prediction errors and thus to maximize learning opportunities.

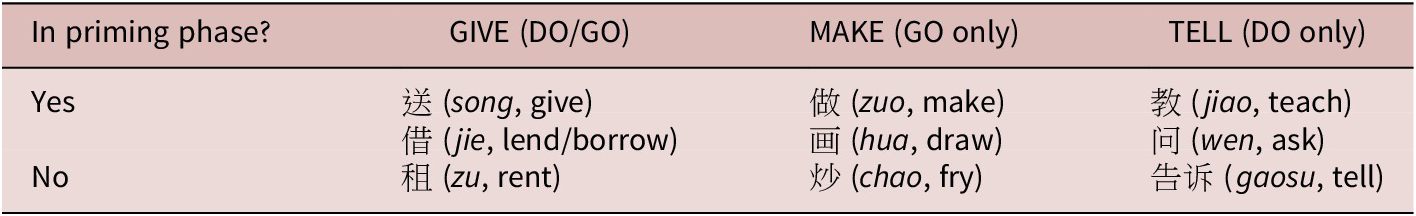

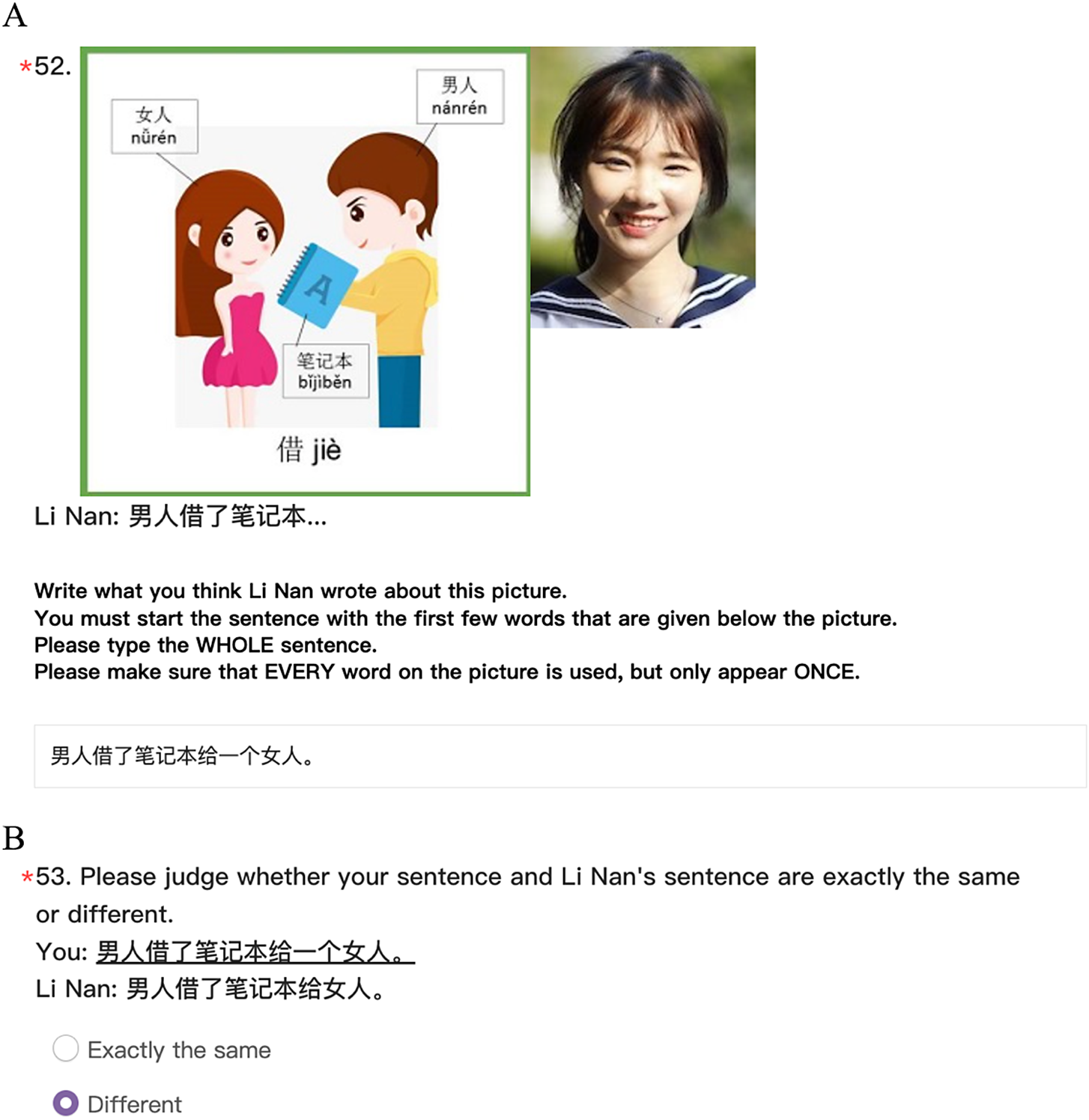

Participants were introduced to the priming task as follows: “In this activity, we would like to see how well you can GUESS how another person (Li Nan) describes pictures in Mandarin.” Then they were provided with some basic information about Li Nan, who was introduced as a native Mandarin speaker attending college in Beijing. Participants were then instructed that their task was to take turns guessing how Li Nan described a picture and describing pictures on their own. On each prime trial (when the picture had a green frame), participants were presented with a labeled picture and a picture of Li Nan and were asked to GUESS what Li Nan had written to describe the picture. The prompt, that is, the first few words of Li Nan’s sentence, was given. Participants had to continue with the given prompt and type their guessed sentence into a textbox (Figure 2, panel A). For example, in Figure 2A, the prompt was “The man lent the notebook …,” which served as a GO prime. After typing their guessed sentence, participants proceeded to the next page, where they were presented with the sentence they just typed, together with the sentence that Li Nan actually produced, and were asked to judge whether the two sentences were exactly the same or different (Figure 2, panel B). They then advanced to the next screen, that is, the target trial, where they wrote their own sentence to describe a picture (Figure 3). They were also provided with a prompt, yet the prompt consisted only of a subject and verb (e.g., “The mom gave…”), thus participants were free to use either DO or GO (or other constructions) on target trials.

Figure 2. Prime trial.

Note. The gloss of Li Nan’s sentence is “The man lent the notebook…”

Figure 3. Target trial.

Note. The gloss of the given sentence is “The mom gave…”

The acceptability judgment tasks

There were two versions of the AJT so each participant received different versions in the pre- and posttest. The assignment of each version to pre- vs. posttest was counterbalanced by participants, such that half of the participants saw version A in the pretest and version B in the posttest, and the other half vice versa. In both versions, there were a total of 42 sentences. The 9 experimental verbs (Table 3) combined with the two dative constructions (DO/GO) yielded 18 experimental sentences, of which 12 were acceptable and 6 unacceptable. There were also 24 filler sentences, 8 acceptable and 16 unacceptable. (See full materials on https://osf.io/v9ej3/)

In the AJTs, participants were asked to judge the acceptability of sentences using a 4-point scale (1–very unacceptable, 2–likely to be unacceptable, 3–likely to be acceptable, and 4–very acceptable). They could also choose “X” if they could not judge a sentence or did not understand it.

Results

The structural priming task

The annotation criteria for sentences produced on target trials in the structural priming task were as follows: (1) sentences were coded as “DO” if they contained the target verb followed by a potential recipient NPFootnote 1 and then a theme NP; (2) sentences were coded as “GO” if they contained the target verb followed by a theme NP, the word GEI, and then a recipient NP; (3) sentences not fitting (1) and (2) were coded as “other,” including various types of appropriate sentences, such as sentences including only one argument (e.g., 经理问了员工的计划。The manager asked the employee’s plan. [literal translation]), serial VP sentences (e.g., 女人做了一个蛋糕送给一个朋友。The woman made a cake gave a friend. [literal translation]), sentences with purposive GEI (e.g., 女人做了一个蛋糕给一个朋友吃。The woman made a cake GEI a friend eat.), V-GEI double object sentences (e.g., 女人送给宝宝一个礼物。The mom give-GEI the baby a gift), and sentences with a preverbal argument preceded by GEI (e.g., 爷爷给奶奶做了鱼。The grandpa GEI the grandma made a fish cuisine.). Twenty percent of the data was annotated by an independent rater; the interrater agreement was 97%.

For the L1 group, “DO” accounted for 44% of all responses, “GO” 45.8%, and “other” 10.2%. For the CL group, the percentages were 42.9% for “DO," 40.0% for “GO” and 17.1% for “other.” The CLs produced 26.8% “other” sentences in the baseline phase and the percentage dropped to 7.3% in the post-priming phase. As “other” sentences comprised a substantial proportion of responses in the CLs, we included “other” responses in addition to “DO” and “GO” in our analyses for both groups. All analyses were conducted in R 4.2.2 (R Core Team, Reference Team2022) using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017).

We ran separate mixed-effect logistic regression models for each semantic verb type (TELL, MAKE, and GIVE) to predict the likelihood of a GO sentence (GO = 1, DO or Other = 0) between task phase (contrast-coded, –.5 = baseline, .5 = post-priming) and group (–.5 =L1, .5 = CL). Task phase, group, and their interaction were included as fixed effects, with maximal random effects of participants and items for the models to converge without error or warning.

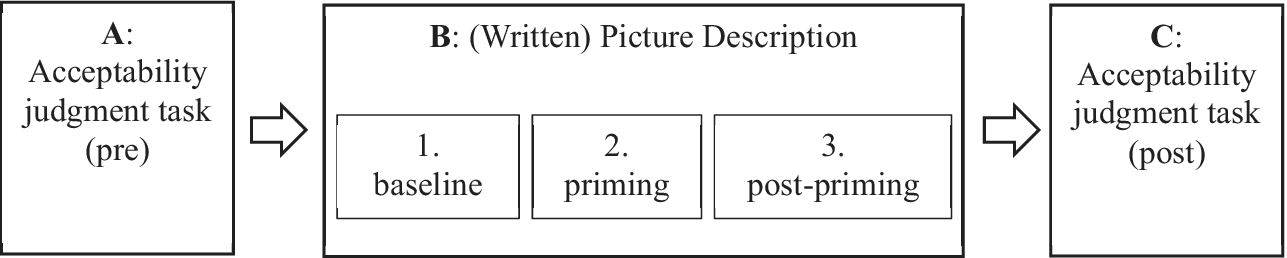

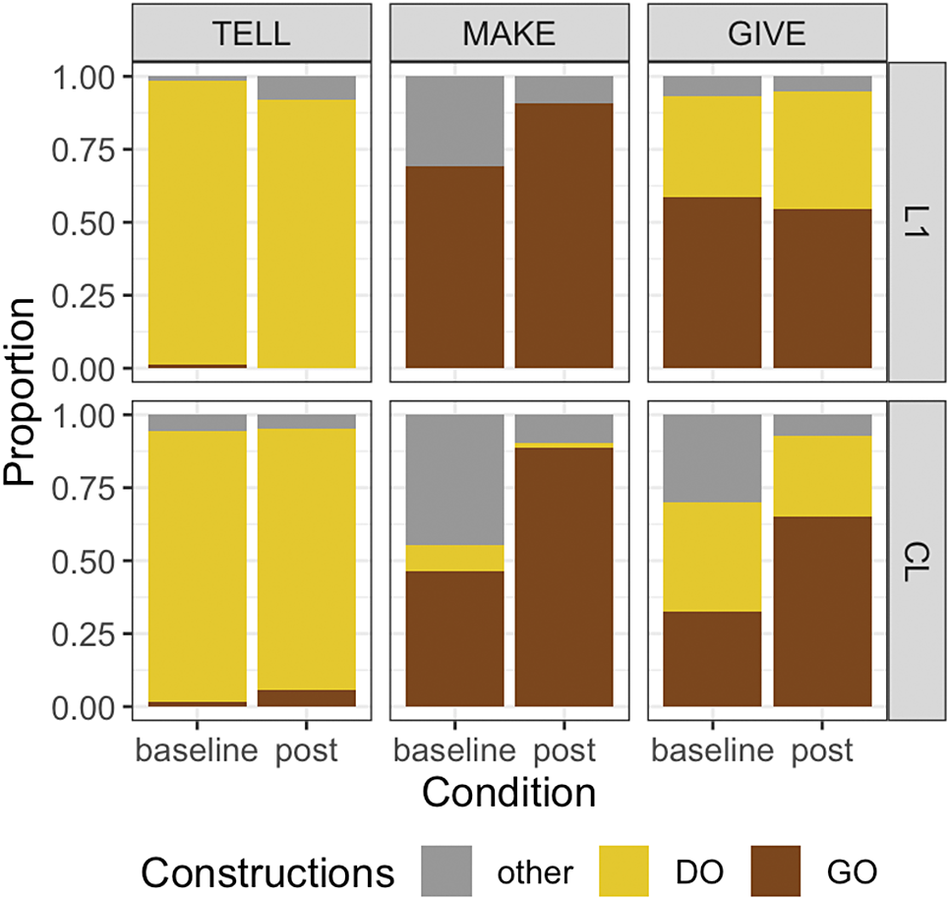

Figure 4 presents the proportion of DO, GO, and other constructions produced by both groups pre- and post-priming (see Table S2 in supplementary materials for descriptive statistics). No changes were observed with TELL verbs since (acceptable) DO productions were at the ceiling from the start for both groups. Both the L1ers and CLs produced more GO constructions with MAKE verbs post- vs. pre-priming. With GIVE verbs, for which the priming phase contained an equal number of GO and DO primes, GO productions increased in the CLs only, yet remained the same in the L1ers. The logistic regression models confirmed these observations.

Figure 4. Proportion of DO, GO, and other constructions produced by group pre- and post-priming.

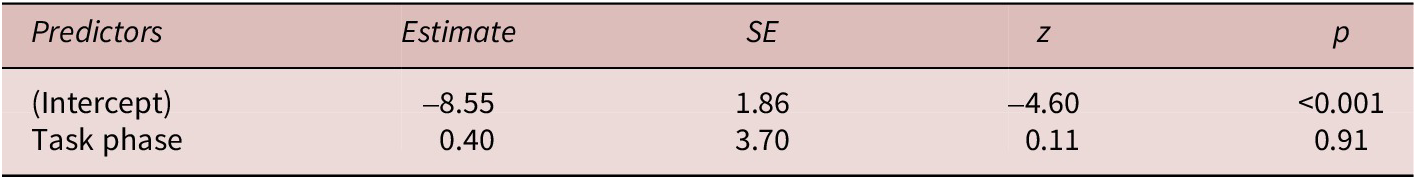

For productions with TELL verbs, overall models and those for the L1 group alone failed to converge, which is unsurprising given the very limited variability in these data. The largest model that converged for responses from the CLs contained task phase as the fixed effect, and random intercepts and slopes for participants only. The output from this model indicates no effect of task phase (Table 4). The CLs produced DOs with TELL verbs at the ceiling from baseline, leaving no room for an increase in TELL-DO pairings.

Table 4. Model output for productions with TELL verbs by the CLs (n = 41)

Formula: glmer(isGO ~ Task phase + (Task phase | participant)).

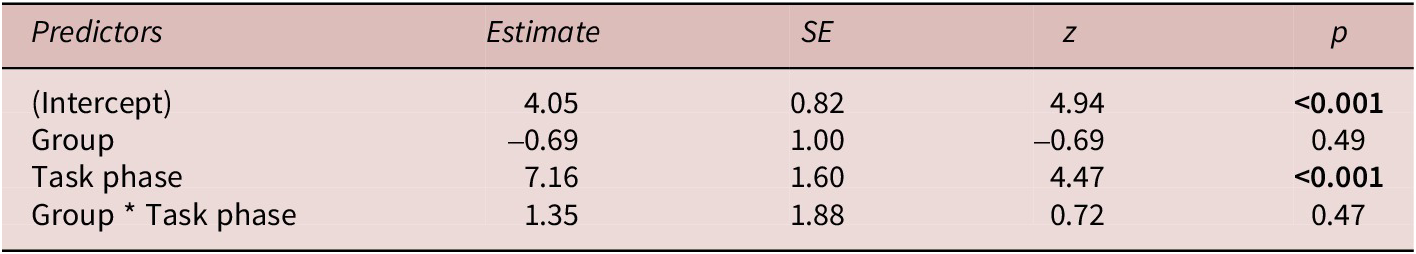

For productions with MAKE verbs, the largest model (see formula and output in Table 5) showed no significant main effect of group (b=–.69, p=.49) or interaction with group (b=1.35, p=.47), but a significant main effect of task phase (b=7.16, p<.001). Both the L1ers and CLs produced more MAKE-GO pairings post-priming vs. baseline.

Table 5. Model output for productions with MAKE verbs (L1ers: n = 25; CLs: n = 41)

Formula: glmer(isGO ~ Group * Task phase + (1+ Task phase | participant) + (1 + Group | item)).

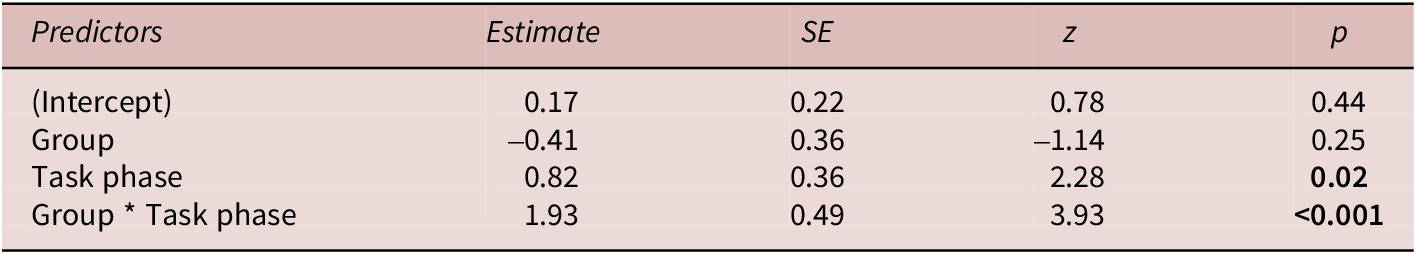

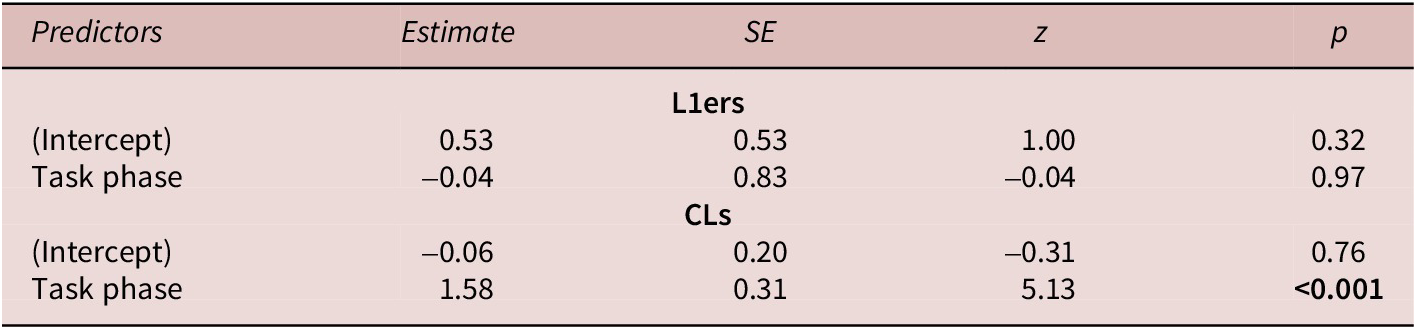

For productions with GIVE verbs (Table 6), there was no significant main effect of group (b=–.41, p=.25). However, we observed a significant main effect of task phase (b=.82, p=.02) and a significant task phase by group interaction (b=1.93, p<.001). Overall, participants were primed to produce more GIVE-GO pairings post-priming vs. baseline. To further explore the interaction, we ran separate models for the two groups. The output from these models (Table 7) indicated that there was no change for the L1ers regarding GIVE-GO productions (b=–.04, p=.97) post-priming vs. baseline; by contrast, the CLs increased their productions of GIVE-GO pairings significantly (b=1.58, p<.001).

Table 6. Model output for productions with GIVE verbs (L1ers: n = 25; CLs: n = 41)

Formula: glmer(isGO ~ Group * Task phase + (1 | participant) + (1 | item)).

Table 7. Model output for productions with GIVE verbs by Group (L1ers: n = 25; CLs: n = 41)

Formula for the L1ers: glmer (isGO ~ Task phase + (1 | participant) + (1 | item)); Formula for the CLs: glmer (isGO ~ Task phase + (1 | participant)).

As stated in the experimental design, one dative verb from each semantic class only appeared in the baseline and post-priming phases, but not in the priming phase (Table 3), to explore whether participants would generalize any potential learning effects to other verbs of the same semantic class, as suggested by Pinker’s semantics-based rule learning approach. For this exploratory analysis, we separated the data of these 3 verbs from those of the 6 verbs included in the priming phase (see Figure S1 in supplementary materials). Given the sparsity of the data, we did not conduct statistical analyses to compare the two, yet visual inspection strongly suggests that participants did not differ in their production patterns with verbs that they had encountered vs. verbs that they had not encountered in the priming phase. More specifically, for the unprimed TELL verb (gaosu, tell), both L1ers and CLs produced DO constructions at the ceiling before and after priming. For the unprimed MAKE verb (chao, fry), both groups increased their GO productions. With the unprimed GIVE verb (zu, rent), only the CLs were primed to produce more GO constructions, while no change was observed for the L1ers. One possible explanation for these similar production patterns between the primed and unprimed dative verbs among the CLs could be semantics-based learning, that is, learners generalize their learned production patterns with the primed dative verbs to other verbs with similar semantic properties. However, it could also be the case that the CLs just generally learned to produce more GOs, regardless of verb type; yet they were very familiar with the unprimed TELL verb (gaosu, tell), and thus used it only with the DO construction across the priming task. Therefore, one must be cautious in interpreting the production pattern with the unprimed dative verbs as a result of semantics-based rule learning.

To sum up, the L1ers and CLs behaved similarly regarding their responses with TELL and MAKE verbs: Both groups almost exclusively produced TELL-DO pairings across the task phase, thus no priming effects with TELL verbs were observed. Both groups were primed to increase their MAKE-GO productions significantly. On the other hand, the two groups differed in response to the GIVE-dative primes. Although both groups received an equal number of GIVE-DO and GIVE-GO primes, only the CLs produced significantly more GIVE-GO pairings post-priming, whereas the L1ers’ productions did not change.Footnote 2, Footnote 3

The acceptability judgment tasks (AJTs)

In the AJTs, participants rated sentences from 1 (very unacceptable) to 4 (very acceptable) and they could choose “X” when they felt unable to judge. After excluding “X” answers (3.26% of all experimental and filler trials; 0.05% for L1ers, 5.23% for CLs),Footnote 4 we converted the remaining responses to z-scores to minimize scale bias (Schutze & Sprouse, Reference Schutze, Sprouse, Podesva and Sharma2014). The z-scores were calculated for each participant using their valid responses to all experimental and filler trials. We ran mixed-effect linear regression models to predict participants’ change of z-score ratings for experimental trials due to priming.

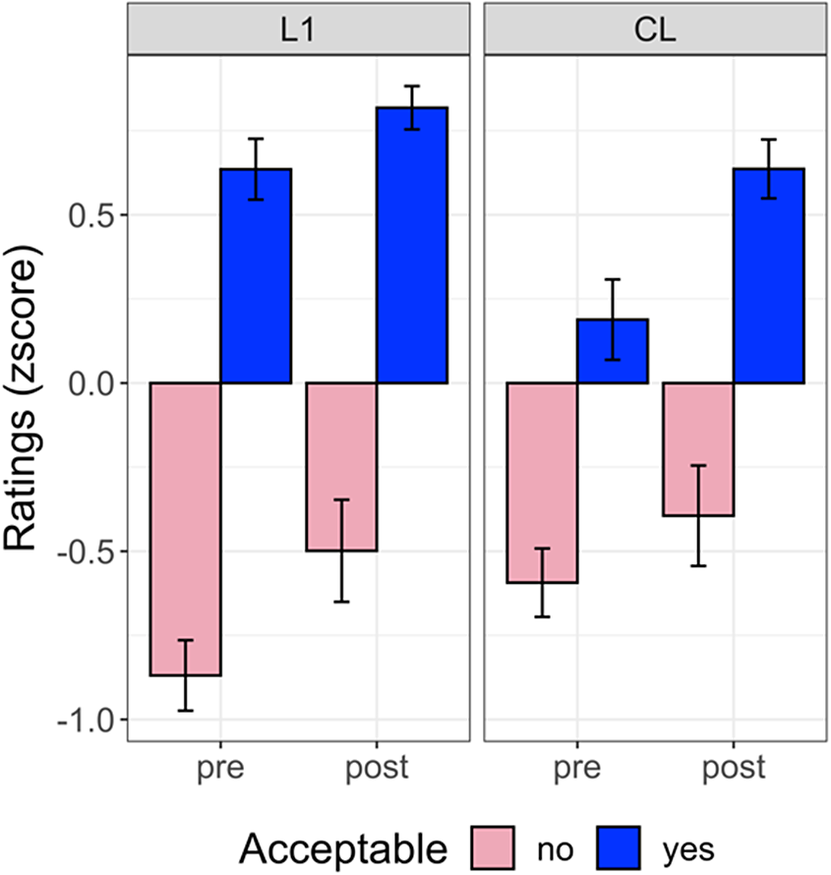

Figure 5 provides a visualization of ratings for the four acceptable (GIVE-GO, GIVE-DO, MAKE-GO, TELL-DO) and two unacceptable (MAKE-DO, TELL-GO) verb-dative pairings in the AJTs before and after priming (see Figure S2 in supplementary materials for ratings by individual pairing). Visual inspection of Figure 5 indicates that ratings for acceptable pairings (blue bars) increased in both groups, yet the increase was larger in the CLs. Unexpectedly, ratings for unacceptable pairings (pink bars) also increased for both groups, although participants did not see these unacceptable pairings during the priming session.

Figure 5. Ratings for acceptable (blue) and unacceptable (pink) verb-dative pairings by group pre- and post-priming. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals on means by participants.

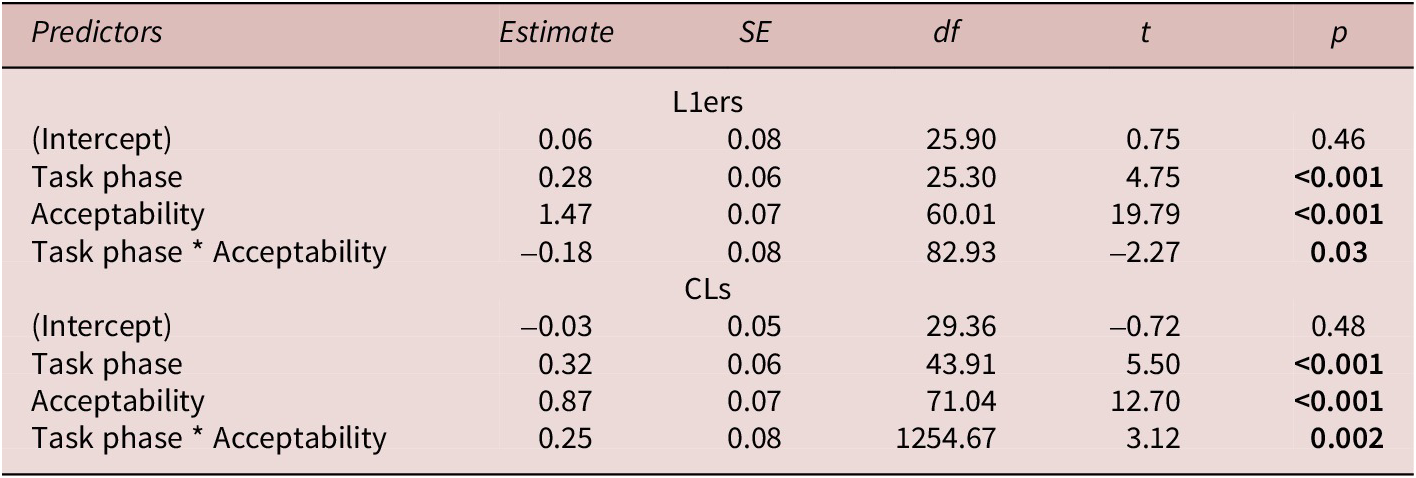

These observations were confirmed with LMER models. The initial model (see Table S10 in supplementary materials) had group (–.5 =L1, .5 = CL), task phase (–.5 = pretest, .5 = posttest), acceptability (–.5 = unacceptable, .5 = acceptable) and their interactions as fixed effects. The maximal random effects for the model to converge included random participant and item intercepts, random participant slopes for task phase and acceptability, and random item slopes for task phase. Due to a significant three-way interaction (b=.44, p<.001), we ran models for the L1 and CL groups separately (Table 8). The model output showed an interaction between task phase and acceptability (b=–.18, p=.03) in the L1 data. Follow-up models on the data split by acceptability indicated that the L1ers increased their ratings for both acceptable and unacceptable sentences post- vs. pre-priming, yet the increase for unacceptable sentences (b=.38, p<.001) was larger than that for acceptable ones (b=.18, p<.001). The CL data also showed an interaction between task phase and acceptability (b=.25, p=.002). Different from the L1 data, follow-up models indicated that this was because the CLs’ increase in ratings for acceptable sentences (b=.44, p<.001) was significantly greater than that for unacceptable ones (b=.19, p=.01).

Table 8. Model output for acceptability ratings by Group (L1ers: n = 25; CLs: n=41)

Formula for the L1 group: lmer (zscore ratings ~ + Task phase * Acceptability + (1 + Task phase | item) + (1 + Task phase + Acceptability | participant)); Formula for the CL group: lmer (zscore ratings ~ + Task phase * Acceptability + (1 | item) + (1 + Task phase + Acceptability | participant)).

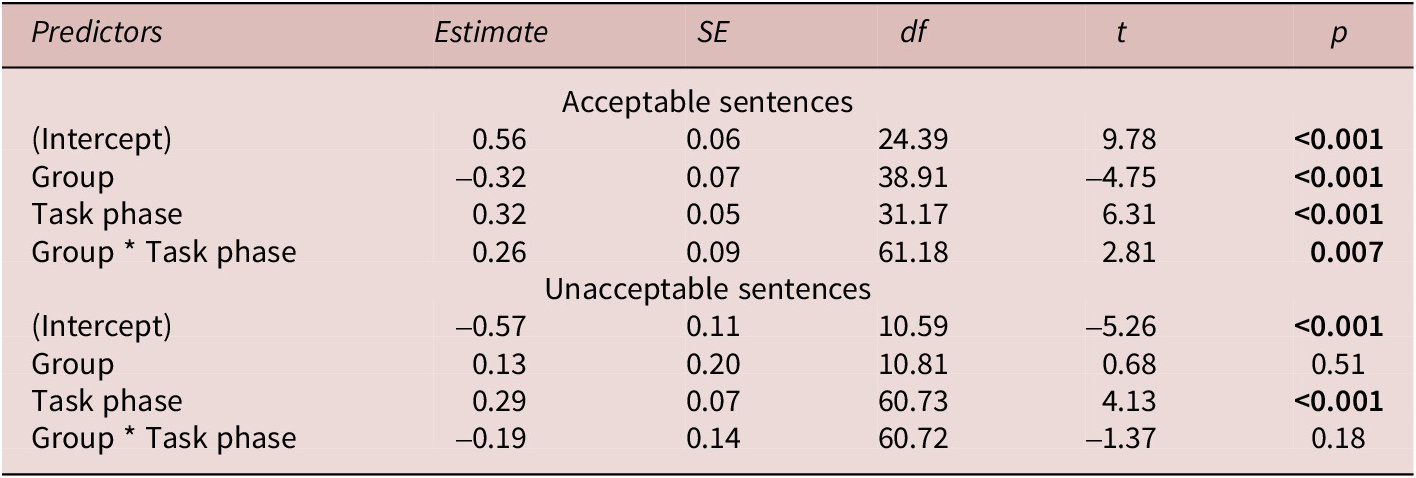

To further explore the three-way interaction in the overall model, we also split the data by acceptability and ran follow-up models (Table 9). For acceptable sentences, there was a significant interaction between group and task phase (b=.26, p=.007). This is because the CL group’s rating increase for acceptable sentences (b=.44, p<.001) was significantly larger than that of the L1 group (b=.18, p<.001). For unacceptable sentences, there was no group by task phase interaction (b=–.19, p=.18), indicating a similar extent of rating increase by the two groups (L1: b=.38, p<.001; CL: b=.19, p=.01).

Table 9. Model output for acceptability ratings by Acceptability (L1ers: n = 25; CLs: n=41)

Formula for Acceptable trials: lmer (zscore ratings ~ Group * Task phase + (1 + Group + Task phase | item) + (1 + Task phase | participant)); Formula for Unacceptable trials: lmer (zscore ratings ~ Group * Task phase + (1 + Group | item) + (1 + Task phase | participant)).

We also conducted exploratory analyses to investigate whether participants showed a similar change of ratings for dative constructions with the 3 unprimed verbs compared to the 6 verbs that appeared during the priming phase. Visual inspection of graphs analogous to Figure 5 (see Figure S3 in supplementary materials) indicated no notable differences in ratings between primed and unprimed verbs in either group.

To summarize, both the L1ers and CLs demonstrated learning effects resulting from priming. Both groups increased their ratings for acceptable verb-dative pairings, yet the increase was significantly larger for the CLs, who had less entrenched linguistic representations and thus were more susceptible to change following positive evidence. Unexpectedly, ratings for unacceptable verb-dative pairings also increased, in both groups to a similar degree. We thus see no support for indirect negative evidence or statistical preemption (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006) leading to lower ratings for unacceptable sentences within this short experiment.Footnote 5, Footnote 6

Discussion

Grounded in error-driven accounts of language learning (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Janciauskas and Fitz2012; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019), this study aimed to examine whether structural priming can boost classroom learners’ (CLs) acquisition of the dative alternation in Mandarin as reflected in (RQ1) their increased production of acceptable verb-dative pairings and decreased production of unacceptable ones, and (RQ2) their increased ratings of acceptable verb-dative pairings and decreased ratings of unacceptable ones. Native speakers and classroom learners of Mandarin completed an acceptability judgment task before and after a structural priming session. In the structural priming session, participants took turns to guess what a native Mandarin speaker Li Nan had written to describe pictures and then compared their guessed description with Li Nan’s actual description (prime trial), and described pictures on their own (target trial).

In terms of learning effects in production, both the L1ers and CLs exhibited longer-term effects, that is, increased productions of the prime verb-dative pairings in a posttest immediately after the priming phase. The results align with Grüter et al. (Reference Grüter, Zhu, Jackson, Kaan and Grüter2021) where Korean-speaking L2 English learners showed longer-term priming effects in an immediate posttest after both the Guessing-Game paradigm of priming and a more standard repetition paradigm. Coumel et al. (Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2023) also found similar longer-term priming effects among both native speakers and L1 French L2 learners of English who listened to or read prime sentences. All three studies revealed longer-term learning effects among L2ers regardless of the priming paradigm, indicating that priming as a learning mechanism, as proposed by EDL models, can extend to L2 learning (but see Jackson & Hopp, Reference Jackson and Hopp2020, who observed longer-term learning among L1ers but not L2ers in a similar baseline-priming-posttest design).

Considering learning effects in production by verb type, we found that with MAKE verbs, both L1ers and CLs were primed to produce more MAKE-GO pairings, which were licit and therefore used exclusively in prime trials. The L1ers never produced illicit MAKE-DO pairings throughout the priming task. On the other hand, 7 out of 41 CLs produced a small proportion (9% in total, see Figure 4) of MAKE-DO pairings in the baseline, and 6 of the 7 CLs stopped using these illicit pairings post-priming. We did not run statistical models regarding this observation because the effect was restricted to a limited number of CLs only. The majority of the CLs never produced illicit MAKE-DO pairings in the first place and thus did not need to unlearn this form. However, this observation at least showed that the CLs in need of unlearning decreased their production of illicit pairings as a result of priming.

With TELL verbs, both L1ers and CLs produced acceptable TELL-DO pairings at the ceiling throughout the task. Only 1 L1er and 2 CLs each produced one case of unacceptable TELL-GOFootnote 7 sentence pre-priming and stopped doing so post-priming. Interestingly, 5 CLs started to produce TELL-GO pairings post-priming, which seems to be a case of overgeneralization, given the newly gained preference for GO constructions overall (and with MAKE and GIVE verbs) among the CLs.

With GIVE verbs, participants were exposed to an equal number of DO and GO primes, yet the L1ers and CLs reacted differently to the identical input. The L1ers maintained their proportions of DO and GO productions post- vs. pre-priming, which appears unsurprising given the equal number of prime trials for the two constructions. In contrast, the CLs showed an increase in the production of GIVE-GO, while their GIVE-DO production decreased numerically. What led to this differential response to the same input? We argue that this differential increase in GIVE-GO vs. GIVE-DO productions among the CLs aligns with EDL accounts (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Dell and Bock2006; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019), which predict greater change for less expected constructions, that is, the inverse frequency effect (e.g., Kaschak et al., Reference Kaschak, Kutta and Jones2011). We assume GO to be less expected to pair with GIVE verbs than DO for the CLs after careful examination of their introductory Chinese textbooks. In the four textbooks of Integrated Chinese (4th Edition) used in the first four semesters of Chinese classes, GIVE verbs are almost exclusively used with DO (for reasons that remain to be determined), even though Mandarin is argued to be strongly GO-biased in terms of the dative alternation with GIVE verbs (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang and Hartsuiker2022). The CLs produced slightly more GIVE-DO (37%) than GIVE-GO (33%) in the baseline, whereas the L1ers had a preference for GIVE-GO (59%) over GIVE-DO (35%). The CLs also produced a considerable proportion (30%) of other constructions in the baseline compared to the L1ers (7% only). Thus, following the logic of error-driven learning, we assume that the CLs tended to predict DO or other constructions with GIVE verbs in the baseline, yet their predictions led to error signals when they encountered GIVE-GO pairings in the priming phase, which caused their adjusted linguistic representations that manifested as increased production of GO with GIVE verbs (65%) post-priming. For the L1ers, on the other hand, the proportions of GIVE-DO and GIVE-GO productions remained similar post-priming vs. baseline, with a slight increase of GIVE-DO (from 35 to 40%) and a decrease of GIVE-GO (from 59 to 55%). We interpret this pattern as resulting from L1ers’ predictions as being mostly affirmed instead of challenged, and they consequently might have experienced fewer prediction errors than the CLs. Error-driven learning accounts thus can explain the lack of priming effects in the L1ers and the inverse frequency effect observed in the CL group with GIVE verbs. Another, not mutually exclusive, explanation for L1ers’ immunity to priming here may be that their representations of the relevant probabilities were more entrenched and thus less susceptible to change from new input.Footnote 8

Turning to the acceptability judgments, we found learning effects in both the L1ers and CLs as ratings for acceptable verb-dative pairings went up in both groups. The size of the rating increase was significantly larger in the CLs. These increased ratings for the acceptable verb-dative pairings to which the participants were exposed during the priming session can be considered learning from positive evidence in the input. The larger effect in the CL group is again consistent with their linguistic representations being less entrenched than those of the L1ers, and therefore more prone to change after receiving positive evidence.

For unacceptable verb-dative pairings, we had predicted—in line with statistical preemption accounts (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019)—that participants may lower their ratings if they had expected these unacceptable formulations (MAKE-DO and TELL-GO) but instead encountered their competing alternatives, that is, MAKE-GO and TELL-DO, and thus repeatedly met with error signals. However, considering participants’ production in the baseline phase of the priming session, we could see that the prerequisite of (un)learning was not met for most of the CLs, that is, they had to predict the unacceptable verb-dative pairings and then be faced with prediction errors. Yet 33 out of the 41 CLs never produced the unacceptable verb-dative pairings, and they differentiated the unacceptable verb-dative pairings from the acceptable ones before priming by rating the former significantly lower than the latter. We must therefore assume that most CLs did not predict to see MAKE-DO and TELL-GO in the first place and therefore encountered no prediction errors regarding these two unacceptable verb-dative pairings. EDL accounts (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Dell and Bock2006; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019) do not argue that the absence of certain language forms alone suffices as evidence of their unacceptability. Thus, one possible explanation for the absence of unlearning here might be a lack of incorrect predictions about MAKE-DO and TELL-GO for error-driven unlearning to happen. We used MAKE and TELL verbs from the textbooks of these classroom learners, and most of them may have already been familiar with the alternation patterns of these verbs. Future research might benefit from utilizing dative verbs whose alternation patterns are less familiar to learners, or other approaches to create an environment for participants to predict unacceptable formulations to occur to test how acquiring what is impossible is realized in error-driven language learning.Footnote 9

Contrary to our expectations, ratings for unacceptable verb-dative pairings increased after priming, for both the L1ers and CLs. What could be the reasons? One possibility is overgeneralization. Learners make overgeneralization errors initially in the process of learning the dative alternation, including L1 learners (e.g., Gropen et al., Reference Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, Goldberg and Wilson1989, on English-speaking children) and L2 learners (e.g., Inagaki, Reference Inagaki1997, on Japanese- and Mandarin-speaking learners of English; Zhu & Zhao, Reference Zhu and Zhao2016, on English- and Japanese-speaking learners of Mandarin). We found that participants in the present study generally rated DO and GO constructions higher in the posttest, regardless of the verbs in them, suggesting some form of overgeneralization. Generalization is crucial for language learning, as it helps us use languages creatively and productively; on the other hand, statistical preemption constrains productivity and helps users recover from overgeneralization (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019). Goldberg proposed that generalization and statistical preemption are two mechanisms working together to achieve successful learning of the dative alternation. Effects of generalization within the course of a short experiment have been documented in several studies (e.g., Brooks & Zizak, Reference Brooks and Zizak2002; Perek & Goldberg, Reference Perek and Goldberg2017), including the current one. However, it appears that statistical preemption was not at play in the present experiment. It is possible and probable that reducing or even eliminating connections between verbs and constructions in learners’ mental representations is a longer process that requires more input. Future work is needed to determine whether such effects could be observed after more extensive priming treatments.

Another phenomenon that might be related to the increased ratings for unacceptable sentences here is syntactic satiation, whose underlying mechanism is still under debate (e.g., Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fanselow, Hall and Kliegl2021; Do & Kaiser, Reference Do and Kaiser2017; Sprouse, Reference Sprouse2009). Syntactic satiation is when some sentences initially judged unacceptable become more acceptable after repeated exposure (Snyder, Reference Snyder2000). Studies showing syntactic satiation effects typically include complex syntactic structures, such as island constraints and other filler-gap dependencies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Fanselow, Hall and Kliegl2021; Do & Kaiser, Reference Do and Kaiser2017), which appear different from the dative constructions in this study. However, Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Fanselow, Hall and Kliegl2021) proposed that satiation applies more broadly to sentences having an initial middle-of-the-scale rating regardless of their constructions. Thus, there is a possibility that participants rated unacceptable verb-dative pairings higher in the post-AJT as a result of having been exposed to these unacceptable sentences in the pre-AJT (note that no unacceptable sentences were primed in the production task). To explore whether satiation might play a role in this study, we also examined ratings for unacceptable fillers in the pre- and post-AJTs (see Figure S4 in supplementary materials). We did not find an increase in acceptability ratings for these fillers in either group. In other words, there were no satiation effects with these unacceptable fillers, although participants were exposed to these sentences in both AJTs as well. Therefore, we argue that the rating increase for the unacceptable verb-dative pairings cannot be fully explained as an effect of syntactic satiation, otherwise, it is hard to explain why satiation would have applied only to the experimental sentences, not the fillers.

To conclude, the current study found that structural priming can facilitate the learning of acceptable verb-dative pairings among classroom learners of Mandarin, as reflected in both their increased production of such pairings and their acceptability ratings. The observation of longer-term priming effects in a posttest, beyond the priming phase itself, with the inverse frequency effect for GIVE verbs observed in the CL group, aligns well with error-driven learning accounts. A question worth future pursuit is how long these learning effects will last. With regard to the effects of statistical preemption, on the other hand, we did not find evidence of decreased acceptability ratings as a result of exposure to competing alternatives. One possible reason might be that participants did not predict the unacceptable verb-dative pairings to occur in the first place. To further explore the potential contributions of statistical preemption to the (un)learning of dative alternation patterns, future studies should try and create circumstances in which participants are more likely to actually predict illicit dative alternatives but encounter only licit ones.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S027226312400041X.

Data availability statement

The experiment in this article earned Open Data and Open Materials badges for transparent practices. The materials and data are available at https://osf.io/v9ej3/

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by an Elizabeth Carr Holmes Scholarship. We are thankful to Shin Fukuda, Li (Julie) Jiang, William O’Grady, and Bonnie D. Schwartz for assistance with various aspects of the study, and to Baorui Xu for assistance with data annotation. We are also thankful to the audience from the Language Acquisition Research Group (LARG) at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, the 2nd International Conference on Error-Driven Learning in Language (EDLL 2022), the 35th Annual Conference on Human Sentence Processing (HSP 2022), and the 34th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-34) for their constructive comments. We extend our thanks to all the participants. We also would like to thank four anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.