Introduction

In September 2014 President Obama announced the formation of a multilateral coalition to ‘roll back’ the terrorist threat emanating from the so-called ‘Islamic State’ in Iraq and Syria (WH, 2014). Footnote 1 Three months later, representatives from across the globe met in Brussels and passed a joint statement that outlined goals in the global fight against Daesh, including the support of ‘military operations, capacity building, and training’, as well as addressing the unfolding humanitarian crisis in the region (DoS, 2014). On November 17, 2015, in the wake of a series of terrorist attacks in Paris, including the bombing at the Bataclan concert hall, and the earlier attacks against the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, France invoked Article 42 (7) of the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty, calling upon European solidarity and assistance in the fight against Daesh (EP, 2015). Three days later, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2249, condemning Daesh for ‘its continued gross systematic and widespread attacks directed against civilians’ and calling upon member states to ‘take all necessary measures in compliance with international law’.

Since 2014, more than 70 states and five international organizations have officially joined the multidimensional fight against Daesh. Footnote 2 In March 2019, the last Daesh-held territory in Syria was re-captured by coalition-backed forces. However, contributions to the US-led military coalition have been characterized by great variance, especially among EU member states. While some states took leading roles in the airstrikes against Daesh, others provided training for local forces, often within the Kurdish Training and Coordination Center (KTCC) in Erbil, and still others did not get involved beyond expressing their political support for the policy. How to explain this variation among EU member states’ contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition? Several studies have documented the early phases of the US-led coalition and explored potential explanations for the observed variance in deployment policies across countries (McInnis, Reference McInnis2016; Saideman, Reference Saideman2016; Haesebrouck, Reference Haesebrouck2018), whereas others have focused on individual countries’ contributions (Doeser and Eidenfalk, Reference Doeser and Eidenfalk2019; Massie, Reference Massie2019; Pedersen and Reykers, Reference Pedersen and Reykers2020), but there has not been a systematic comparison of EU member state involvement in the fight against Daesh. Footnote 3 Since the 2015 incident was the first invocation of the Lisbon Treaty’s mutual defense clause, it is of particular policy relevance to conduct such a comparison across EU members and their foreign and security policies. Focusing on the nexus between international and domestic politics, this paper also speaks to the dynamics of multilateral military coalitions that have become pervasive in international security, as nearly all contemporary conflicts occur in the context of alliances, coalitions, or international organization auspices (Kreps, Reference Kreps2011; von Hlatky, Reference von Hlatky2013; Auerswald and Saideman, Reference Auerswald and Saideman2014; Weitsman, Reference Weitsman2014; Mello and Saideman, Reference Mello and Saideman2019; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2019).

Against this backdrop, the article makes a two-fold contribution to the literature on security policy and participation in military coalitions. Empirically, it provides a mapping of the then 28 EU member states’ military engagement in the fight against Daesh in Syria and Iraq, whose contributions ranged from combat involvement in the air strikes, air support functions, the provision of training to local forces, to mere political and/or logistical support for the coalition. Analytically, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is applied to develop a configurational account for the observed pattern of EU involvement in the anti-Daesh coalition, based on an integrative theoretical framework that combines international- and domestic-level factors, which are conceptualized as incentives and constraints for decisions on military involvement. The conditions include the number of citizens who joined Daesh as foreign fighters (as an indicator for an external threat), the value placed on a country’s alliance relationship, the political left-right position of its government, the presence of parliamentary veto rights over military deployments, and a measure of the extent to which the public perceives terrorism and foreign fighters as a security challenge. As a set-theoretic comparative method, QCA is ideally suited to account for complex causation, indicated by the presence of multiple paths (equifinality) and combinations of conditions (conjunctural causation) leading to an outcome. This makes it a suitable methodological choice for this study because none of the explanatory conditions are expected to be individually necessary and/or sufficient. To the contrary, theory and prior work suggest combinations of conditions and alternative paths towards the outcome.

Indeed, the results demonstrate that multiple paths led towards EU military involvement in the anti-Daesh coalition. At the same time, international-level incentives, such as external threat and/or alliance value feature prominently in all three identified paths. Moreover, the analysis underscores the value of a configurational perspective because neither external threat nor alliance value are sufficient on their own to bring about the outcome. Across the configurations entailed in the set-theoretic solution, these either combine with other ‘push’ factors or with the absence of constraints against military involvement. In line with the latter, the paper highlights the policy relevance of institutional constraints, especially legislative veto rights, since most of those countries that were involved in the airstrikes of the anti-Daesh coalition did not have formal parliamentary involvement on matters of military deployment policy (Ruys et al., Reference Ruys, Ferro and Haesebrouck2019). This suggests that legislative veto rights can, under certain preconditions, constrain the war involvement of democracies, which resonates with prior studies’ findings (Dieterich et al., Reference Dieterich, Hummel and Marschall2015; Wagner, Reference Wagner2018) and underlines the political importance of this institutional constraint.

The article proceeds in four steps. The next section develops the integrative theoretical framework to account for EU contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition. This is followed by an introduction to the article’s method and data. The ensuing section contains the set-theoretic analysis of EU countries’ military contributions and a discussion of the analytical results. The article concludes by summarizing its findings, outlining the relevance for studies on security policy and coalition warfare, describing inherent limitations of the present study, and suggesting directions for future research.

Accounting for military contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition

Why do states decide to join military coalitions? Prior studies alternately emphasize the importance of alliance membership (Snyder, Reference Snyder1997), threat perception (Walt, Reference Walt1987), international hierarchy (Lake, Reference Lake2009), alliance value (Davidson, Reference Davidson2014), or diplomatic embeddedness (Henke, Reference Henke2017) as reasons why states decide to join military coalitions. Apart from these general explanations, for the anti-Daesh coalition it might have also mattered that many countries did not want to repeat their experiences from the long-lasting campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq (Saideman, Reference Saideman2016; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2019). Moreover, domestic institutions and politics may have played important roles in the decision-making processes on whether or not to participate militarily in the coalition (Milner and Tingley, Reference Milner and Tingley2015). Decisions on military contributions are usually decided at the cabinet level, which means they are subject to party politics (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017). Governments further operate under institutional and legal constraints, such as parliamentary veto rights over military deployments (Peters and Wagner, Reference Peters and Wagner2011; Ruys et al., Reference Ruys, Ferro and Haesebrouck2019) and they usually observe public opinion, which can form an additional constraint against military involvement (Baum and Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2015; Everts and Isernia, Reference Everts and Isernia2015). Building on previous efforts to combine such international and domestic-level explanations (e.g., Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Lepgold and Unger1997; Haesebrouck, Reference Haesebrouck2018; Massie, Reference Massie2019; Mello, Reference Mello2019), this article develops an integrative theoretical framework to explain EU member states’ military contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition in Iraq and Syria, as outlined in the following sections.Footnote 4

External threat

From a realist perspective, a primary driver of why states join a military coalition or increase their allied cooperation is that they feel threatened (Walt, Reference Walt1987). The swift rise of Daesh combined with an apparent increase in terrorist activity in Europe and elsewhere certainly increased leaders’ willingness to ‘do something’ about this new phenomenon (Gerges, Reference Gerges2016), especially after the occurrences in Paris in January 2015, when terrorists killed 12 people in their attack on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, and during the series of terrorist attacks in November 2015, including the bombing at the Bataclan concert hall where 130 people were murdered, after which France subsequently invoked Article 42 (7) of the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty, calling upon European solidarity in the fight against Daesh. This was compounded by reports about a steady flow of foreign fighters arriving in Syria and Iraq to join Daesh (UNODC, 2019). While estimates vary, most reports came to the conclusion that a substantial share of the 30,000 foreign fighters who joined Daesh originated from Western Europe, including large numbers from France, Germany, and the UK, and smaller numbers from Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden (Dodwell et al., Reference Dodwell, Milton and Rassler2016; TSC, 2017).Footnote 5 Since some of these foreign fighters have committed extreme acts of violence in Daesh-held territory, and others have engaged in terrorist activities in third countries, their eventual return to their countries of origin was seen as a grave security threat in many European states. Hence, the external threat perspective suggests that countries with foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq had a particular incentive to join the anti-Daesh effort.

Alliance value

Another explanation for military involvement in coalition operations pertains to the value that states place on their alliance relationship (Davidson, Reference Davidson2014; Massie, Reference Massie2019). This is related, but not identical to long-standing arguments about alliance dependence (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Lepgold and Unger1997; Snyder, Reference Snyder1997). Accordingly, states may value a security alliance and their relationship with an alliance leader for different reasons. These may be related to their security needs, but the reasons can also derive from status seeking (Pedersen and Reykers, Reference Pedersen and Reykers2020), concerns about reputation (Oma and Petersson, Reference Oma and Petersson2019), or economic incentives (Newnham, Reference Newnham2008; Henke, Reference Henke2019). For example, Eastern European countries – particularly the Baltic states and Poland – value NATO membership and their close relations with the USA because this serves as a credible security guarantee against the threat posed by neighboring Russia (Doeser and Eidenfalk, Reference Doeser and Eidenfalk2019). Others, such as Denmark, the Netherlands, or the UK, traditionally regard a close relationship with the USA as a way to maintain international influence and standing (Ringsmose, Reference Ringsmose2010).Footnote 6 Applying such arguments to NATO, Ringsmose (Reference Ringsmose2010, 331) distinguishes between ‘Article 5ers’ and ‘Atlanticists’. The former are states that feel insecure or threatened and thus emphasize NATO’s mutual defense clause. The latter are countries that traditionally maintain ‘special relationships’ with the USA. Both of these groups would be expected to support and contribute to US-led military operations, like the anti-Daesh coalition, even when such a mission is conducted outside the official organizational framework of NATO.

Parliamentary veto rights

Recent institutionalist work has explored the role of parliaments in security policy and investigated the effects of specific forms of institutional constraints, such as constitutional restrictions and parliamentary veto rights on the security policies of consolidated democracies (Peters and Wagner, Reference Peters and Wagner2011; Dieterich et al., Reference Dieterich, Hummel and Marschall2015). This literature emphasizes that decisions about military deployments are often dependent upon structural and procedural restrictions, and that parliaments are important actors also in security policy, particularly, but not exclusively, when legislatures hold a formal veto right over military missions (Kesgin and Kaarbo, Reference Kesgin and Kaarbo2010; Oktay, Reference Oktay2018; Coticchia and Moro, Reference Coticchia and Moro2020). While mandatory parliamentary involvement can also yield unintended consequences (Lagassé and Mello, Reference Lagassé and Mello2018), the general expectation is that whenever legislatures have a say on military missions this creates an additional hurdle for government engagement. To be sure, this is not an absolute constraint. But when there is substantial public opposition, then military contributions are not expected to be approved by parliament.Footnote 7 Moreover, due to a fusion between government and opposition in parliamentary democracies, such preferences against military engagement will often be anticipated by governments. This means that, more often than not, governments will refrain from submitting a motion on a military deployment if they have reason to fear a parliamentary veto on the issue.Footnote 8

Party politics

The realist conjecture that ‘politics stops at the water’s edge’ has long dominated IR thinking about partisanship and security policy (Gowa, Reference Gowa1998; Milner and Tingley, Reference Milner and Tingley2015). Yet an emerging literature shows that ideological differences between parties on the left and the right also affect the way that parties formulate foreign and security policies and how they implement these once in government (Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2013; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017; Coticchia and Vignoli, Reference Coticchia and Vignoli2020; Wenzelburger and Böller, Reference Wenzelburger and Böller2020). For instance, Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017) demonstrate that while right-of-center parties are generally more supportive of military missions, there’s a curvilinear relationship with decreasing support towards both ends of the political spectrum. Yet, when examining actual involvement in military operations, Haesebrouck and Mello (Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020) find that ‘left-wing governments were more inclined to participate’ (2020, 581). Given this mixed evidence, it is difficult to derive clear-cut expectations on partisanship for the anti-Daesh coalition. On the one hand, coalition activities are multi-faceted and range from airstrikes to training of local forces and humanitarian aid. On the other hand, the military effort is decidedly ‘robust’, and it takes place outside the organizational frameworks of NATO or the EU. On this basis, right-of-center governments may be expected to be more supportive of actually deploying forces than their left-leaning counterparts.

Public opinion

Public opinion is a central building block in many theories of the democratic peace and democratic conflict behavior more generally (Doyle, Reference Doyle1983; Everts and Isernia, Reference Everts and Isernia2015; Ozkececi-Taner, Reference Ozkececi-Taner and Thompson2017). The reasoning behind the idea of a ‘public constraint’ goes back to Kant’s famous proposition that citizens would decide against war if they had a say in the decision, assuming that they would have to bear the brunt of the burden of warfighting (Kant, Reference Kant2007, 100). Yet, when applied to a contemporary context, we may call into question whether the public truly constitutes a constraint on government behavior because the population is unequally affected by the human and material costs of war (Kriner and Shen, Reference Kriner and Shen2010). However, as studies have shown, given that certain preconditions are met, public opinion can stop governments from unpopular military engagements. For instance, Dieterich et al. (Reference Dieterich, Hummel and Marschall2015) show that war-averse publics, combined with institutional constraints, stopped many European governments from becoming engaged in the Iraq War. More generally, Baum and Potter (Reference Baum and Potter2015) argue that public opinion and media access are key variables to understand democratic constraint in foreign policy. From this perspective, public support, or a lack thereof, can be seen as a key element to account for decisions on military engagements. As developed below, this paper’s empirical focus rests on public threat perception, understood as the extent to which citizens regard terrorism and foreign fighters as an important security challenge for the European Union.

An integrated model of coalition contributions

Given the inherent multi-dimensionality of foreign policy decision-making, it seems appropriate to expect complex interactions between the various relevant factors outlined in the previous section. Against this backdrop, it is important to underline that none of the five aforementioned factors is expected to independently account for the observed variance in military contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition. Instead, I expect these conditions to form combinations of conditions that either push towards military contribution or constrain a military engagement. The first two factors, external threat and alliance value are both expected to be push factors that motivate governments to join the anti-Daesh coalition. To the contrary, parliamentary veto rights and a lack of public threat perception are considered to be constraints on government assertiveness. Their combination is expected to be sufficient for the absence of military participation (non-outcome). As mentioned above, party politics can cut both ways (Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004). Yet, the general expectation would be that right-of-center governments are more willing to contribute militarily than their left-leaning counterparts (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017), especially for military operations that are aimed at fighting terrorism, such as the anti-Daesh coalition, even though recent work suggests that left governments might be more inclined to become involved militarily (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020). From a methodological angle, each individual factor is regarded as an INUS condition, which is ‘an insufficient but necessary part of a condition, which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the result’ (Mackie, Reference Mackie1965, 245). INUS conditions essentially encapsulate the idea of causal complexity that is central to Qualitative Comparative Analysis and their conceptualization has informed numerous QCA applications (see, for instance, Ide, Reference Ide2018). The method of QCA is introduced in the next section.

Method

This paper uses fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA; Ragin, Reference Ragin2008) to investigate the expected complex interaction between explanatory factors. As a set-theoretic method, QCA aims at identifying necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. QCA is ideally suited to recognize the combination of more than one factor (conjunctural causation) and the existence of multiple pathways toward an outcome (equifinality). While QCA is widely used in many areas of the social sciences (Rihoux et al., Reference Rihoux, Álamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013), it can still be considered a novel approach in international relations, and conflict research in particular. That being said, recent years have seen a number of QCA applications in these fields, including on topics such as sanctions against authoritarian regimes (Grauvogel and von Soest, Reference Grauvogel and von Soest2014), peace agreements (Caspersen, Reference Caspersen2019), international arms control treaties (Böller, Reference Böller2021), post-conflict gender equality (Bhattacharya and Burns, Reference Bhattacharya and Burns2019), coalition defection in multilateral military operations (Mello, Reference Mello2020), or the effectiveness of international peacebuilding (Mross et al., 2021).

In contrast to the crisp-set variant of QCA, which works with binary values, fuzzy-set QCA allows researchers to take into account qualitative and quantitative differences (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). Fuzzy sets can assume any value between 0 and 1. Using a software-based procedure,Footnote 9 quantitative datasets can be calibrated into fuzzy sets by assigning three empirical anchors, which are determined by the researcher.Footnote 10 These three thresholds designate which scores in the data are considered ‘fully in’ a specified fuzzy set (resulting in a fuzzy value of 1), which scores are regarded as ‘neither in nor out’ (these receive a fuzzy value of 0.5), and which scores are ‘fully out’ of the respective set specified (receiving a fuzzy value of 0). The ‘direct method of calibration’ applies a logistic function that transforms the raw data into fuzzy values, based on anchors set by the researcher (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). This procedure returns fine-grained fuzzy values that show whether a case is qualitatively rather inside or outside a set and to what quantitative extent the case shows membership in a given fuzzy set.

Recent work emphasizes that crisp sets and fuzzy sets can, occasionally, yield different results (Rohlfing, Reference Rohlfing2020, 86). As a robustness test, I complemented the fuzzy-set analysis with a crisp-set alternative. Table A5 (online appendix) shows that the results are substantively identical, while crisp sets lead to perfect consistency, PRI, and coverage scores. This means that the results are robust, irrespective of which type of set is chosen. In line with good practices of calibration (Skaaning, Reference Skaaning2011; Duşa, Reference Duşa2019; Mello, Reference Mello2021; Oana et al., Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021), I also report the calibration ranges within which the results of the set-theoretic analysis do not change. The SetMethods package for R provides a function to conduct such a test (Oana and Schneider, Reference Oana and Schneider2018; Oana et al., Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021), the results of which are reported in Table A1. Other robustness tests concern the coding of the outcome and a restricted model of conditions (see Tables A6 and A7 in the appendix). The first test confirms that the results are not sensitive to a different assignment of scores, such as when lower-level military involvement is assigned more weight in the calibration, whereas the second effectively yields Path 2 of the reported intermediate solution (Table 1).

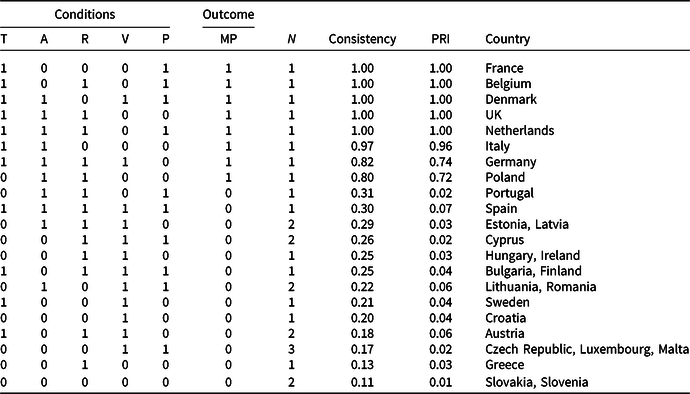

Table 1. Solution paths for military participation in the anti-Daesh coalition

Note: Black circles indicate the presence of a condition, crossed-out circles its absence. The solution entails two logically equivalent models. Model 2 was chosen for the substantive interpretation due to its higher solution consistency and coverage. For a comparison, see Table A3.

Military participation in the anti-Daesh coalition

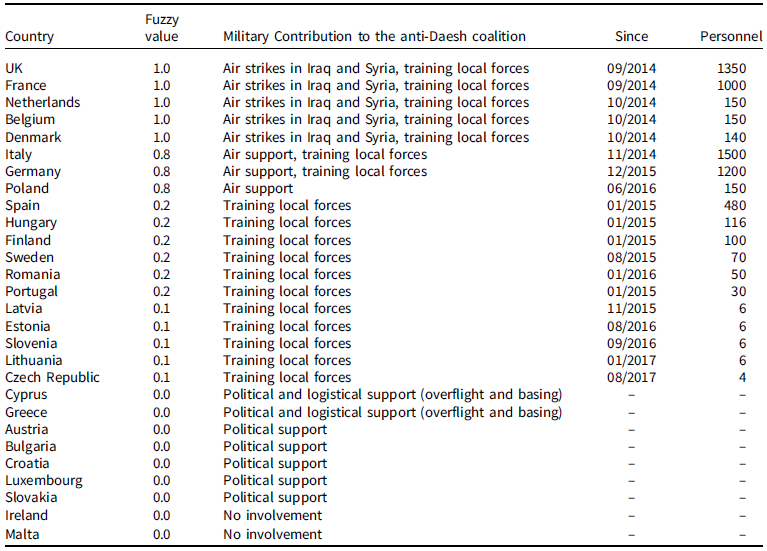

The outcome to be explained is the military participation of the EU − 28 in the anti-Daesh coalition, also known as operation “Inherent Resolve”. The multilateral coalition was formed under President Obama in September 2014 (WH, 2014),Footnote 11 after a request from the Iraqi government. Military operations against Daesh were initially limited to Iraqi territory and subsequently expanded to Syria (in 2015–16). Combat intensity reached peaks in the summer of 2017, when the UK-based NGO “Airwars.org” reported civilian deaths due to airstrikes by the US-led coalition of up to 2,600 in Iraq and 1,300 in Syria.Footnote 12 Table 2 summarizes military contributions across the EU−28 (including the UK before Brexit).Footnote 13

Table 2. Military contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition

Sources: Own compilation based on Drennan (Reference Drennan2014), McInnis (Reference McInnis2016), Saideman (Reference Saideman2016), information from ministries of defense, and the coalition website: http://theglobalcoalition.org (accessed October 8, 2020).

Essentially, there are three groups of countries. The first group includes those that were actively involved in the airstrikes, either by bombing targets themselves (UK, France, Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands) or through the provision of air support or reconnaissance operations (Germany, Italy, and Poland). Notably, contributions in this category were made at different points in time. Whereas the UK and France conducted airstrikes from September 2014 onward, Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands followed a month later. Italy deployed reconnaissance aircraft in November 2014, while Germany followed in similar functions in December 2015, and Poland in June 2016. The second group of countries contains those who limited their contribution to training local forces, mostly at the Kurdish Training Coordination Center (KTCC) in Erbil, but also in other locations. While all of these were small-scale training missions, some countries deployed substantial numbers (between 30 and 500 soldiers, including Spain, Hungary, Finland, Sweden, Romania, and Portugal), whereas others send only a handful of officers for the instruction of local forces (the Baltic countries and Slovenia). Finally, a third group of countries made no material contributions beyond logistics (overflight and basing rights in Greece and Cyprus) or expressions of political support (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Luxembourg, and Slovakia). Two countries did not officially endorse the anti-Daesh coalition (Ireland and Malta).

Fuzzy values reflect the primary criterion of whether countries were involved in the airstrikes, with slightly lower values assigned to those who restricted their contribution to air support. While training contributions often also entailed substantial military personnel, these were assigned lower scores due to the different qualitative nature of the involvement. From the perspective of democratic politics, key questions concern the risks associated with a military deployment and the legality and legitimacy of the mandate. Hence, the fuzzy values reflect the major difference between contributing to the airstrikes (which often requires parliamentary approval) and other kinds of contributions, which are often outside the scope of parliamentary veto rights and receive substantially less attention in parliament and among the public.Footnote 14

Explanatory conditions: data and calibration

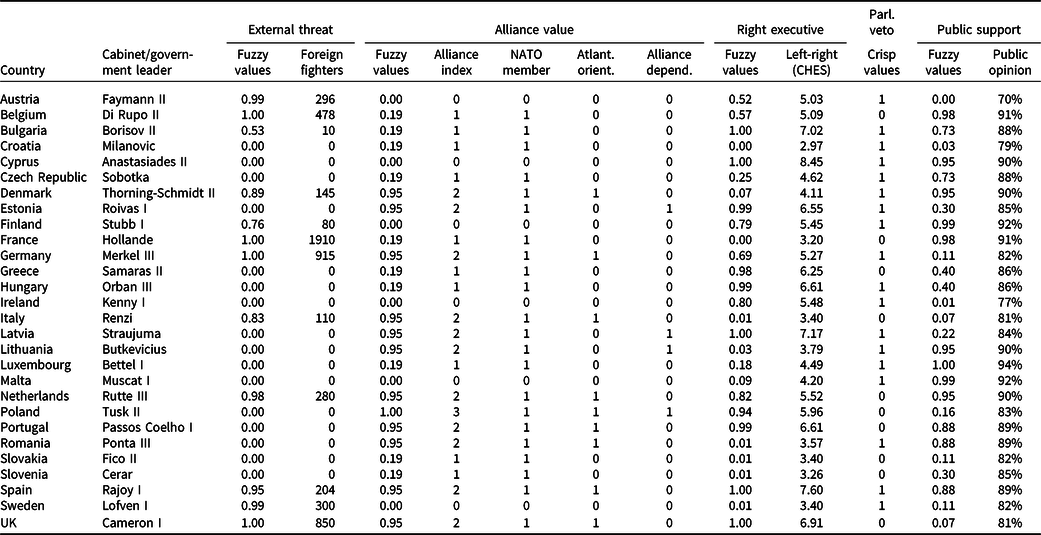

The set-theoretic analysis contains five explanatory conditions: external threat (T), alliance value (A), right executive (R), parliamentary veto rights (V), and public threat perception (P). Table 3 lists the EU − 28 by relevant cabinet or government leader and provides raw data and calibrated fuzzy values for the included conditions. This section summarizes the fuzzy-set calibration of the included conditions and outcome, which is the transformation of qualitative and/or quantitative raw data into set-theoretic membership scores used for QCA (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012; Mello, Reference Mello2021). Additional documentation is given in the online appendix.

Table 3. EU governments and explanatory conditions

External Threat indicates whether citizens of the respective state have gone to Syria or Iraq to join Daesh as foreign fighters. Data on foreign fighters stems from the Soufan Center and Global Strategy Network (TSC, 2017). Given the nature of the phenomenon, the numbers cited remain estimates, albeit most of these have been confirmed in later investigations (see also UNODC, 2019). For September 2015, a total of 30,000 foreign fighters from over 100 countries were estimated to be in Syria. About 5,000 of these came from EU countries. The empirical pattern is relatively clear-cut: 12 EU states had citizens who joined Daesh as foreign fighters, many of these countries also experienced deaths from jihadi-motivated terrorist attacks on their own soil.Footnote 15 The fuzzy-set condition external threat was calibrated so that all countries with foreign fighters receive fuzzy-set values above 0.50, whereas those without received a value of 0. Countries with 200 or more foreign fighters were considered ‘fully inside’ the set external threat.

Alliance Value reflects whether a country has specific incentives to contribute militarily, rooted in its alliance relationship. The measure rests on an aggregate index that takes into account: (1) whether the country has a formal alliance membership in NATO; (2) is considered dependent on the alliance for its security; and (3) whether it is generally regarded as following an Atlanticist foreign policy orientation. The first indicator simply distinguishes between NATO and non-NATO members. The second indicator, alliance dependence reflects the security concerns of countries like the Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – as well as Poland. Due to their conflictive neighborhood with Russia, these four EU members have the greatest interest in securing a strong partnership with the USA and therefore seek to maintain a status as loyal NATO members. Finally, the third indicator takes into account countries with a strong Atlanticist foreign policy orientation such as the UK, Denmark, and the Netherlands, as apparent from the UK’s traditional ‘special relationship’ with the USA or the Danish ‘opt-out’ from the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). My estimate of Atlanticist foreign policy orientation follows prior work in its classification (Asmus et al., Reference Asmus, Everts and Isernia2004; Biehl et al., Reference Biehl, Giegerich and Jonas2013; GMF, 2014). To be considered inside the set ‘alliance value’, a country needs to effectively show two out of three indicators. Hence, based on the aggregate alliance index, countries with a score of 1.25 and above are considered rather inside the set alliance value, whereas scores of 2 and above indicate full membership and less than 0.75 full non-membership. This means that all countries that score on two or more dimensions of the index are considered fully inside the set alliance value and those that score on a single dimension are considered rather outside the set. Table 3 displays the individual scores and the resulting fuzzy values for this condition.

Right Executive refers to governments’ political positions on a left-right scale. The estimate draws on partisanship data provided by the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2018), which in turn originates from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES, Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudová2015). Since many of the EU − 28 have coalition governments, parties’ individual left-right scores and their parliamentary seat share was used to calculate a weighted left-right score for the overall government. The general left-right variable in the CHES data runs from 0 for extreme left to 10 for extreme right. Using the direct method of calibration, this data was turned into fuzzy values where a score of 5 is a natural cross-over, resulting in fuzzy values of 0.50, and 6 and 4 were used as upper and lower boundaries (fully inside and fully outside the set ‘right executive’, respectively).

Parliamentary Veto Rights reflects a legislature’s formal right to veto military deployments. The key distinction is whether or not a parliament enjoys the right to debate and decide upon military missions before the armed forces are dispatched. If such a formal veto right exists, the respective country is coded as 1, if not it is assigned a score of 0. My estimate primarily draws upon the ParlCon data set (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Peters and Glahn2010) and subsequent updates (Wagner, Reference Wagner2018), as well as data from the PAKS project (Dieterich et al., Reference Dieterich, Hummel and Marschall2015).Footnote 16 Of the EU − 28, a total of 18 countries have parliamentary veto rights that apply to ad hoc coalitions such as the anti-Daesh coalition. Notably, some countries adopt different procedures depending on whether an operation takes place within the institutional context of NATO, CFSP, or as part of an ad hoc coalition of countries.Footnote 17 Several countries have also amended their constitutions in recent years, such as Spain, France, and Italy.Footnote 18

Finally, High Threat Perception reflects European citizens’ attitudes towards terrorism and the foreign fighters phenomenon and whether people believed that terrorism and foreign fighters would pose increased security challenges for the EU in the coming years. My estimate draws on data from a Special Eurobarometer survey on European citizens’ attitudes towards security (EC, 2015). The survey was requested by the European Commission and conducted in March 2015, when the terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, which occurred on January 7, 2015, were still fresh in people’s minds (EC, 2015). The survey collected responses from 28,083 Europeans across all EU member states, which makes it a suitable choice for this study.Footnote 19 On average among the EU − 28, 68% of the respondents said that the security challenge from terrorism and foreign fighters was likely to increase, with responses from individual countries ranging from 42% in Latvia and 44% in Lithuania to 79% in Germany and 80% in the Netherlands. Accordingly, countries were coded as being ‘fully inside’ the set high threat perception if 70% or more of the respondents saw an increased security challenge from terrorism and foreign fighters. The 0.50 cross-over was set at 62.5%, which effectively separates the group of countries with average to high responses (65% and higher) from those with below-average responses (60% and less). Scores below 50% were considered ‘fully outside’ the set high threat perception. Table 3 lists the raw data and calibrated fuzzy values for the included conditions. Table A1 and Figure A1 in the appendix provide additional documentation.

Set-theoretic analysis

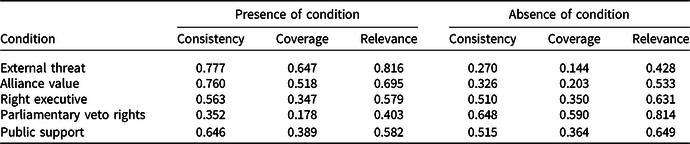

The first stage in the analytical procedure of QCA is the testing for necessary conditions. Table 4 shows that none of the five included conditions passes the conventional threshold of 0.90 consistency (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), and thus none can be considered necessary for the outcome of military participation in the anti-Daesh coalition. This also holds for the absence (negation) of each of the included conditions.

Table 4. Testing for necessary conditions

The second stage is the truth table analysis, which aims at identifying individual conditions or combinations of conditions that consistently lead towards the outcome. Table 5 displays the truth table for the outcome military participation in the anti-Daesh coalition (MP) and the explanatory conditions, external threat (T), alliance value (A), right executive (R), parliamentary veto rights (V), and public threat perception (P). With five conditions, this explanatory model entails 25 = 32 rows of logically possible combinations of conditions. As indicated in the table, rows 22 to 32 are omitted, because these do not contain any empirical cases. These are logical remainder rows, which can be incorporated in the minimization to derive QCA solution terms.

Table 5. Truth table for military participation in the anti-Daesh coalition

Notes: T = external threat; A = alliance value; R = right executive; V = parliamentary veto rights; P = public support; MP = Military Participation, bold cases hold membership >0.50 in the outcome.

Empty rows are omitted for presentational purposes (see online appendix for a table with logical remainders).

As measures of fit, Table 5 shows ‘consistency’, which reflects the extent to which a row (combination of conditions) is sufficient for the outcome MP. The second indicator is ‘PRI’, which refers to the ‘proportional reduction in inconsistency’. This measure can help to identify ambiguous subset relationships, which can be the case if PRI is considerably lower than consistency (see Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012, 242). To minimize the truth table and to derive solution terms, a consistency cut-off point is set by the researcher. This indicates which rows are considered to be consistent enough to be included in the ensuing Boolean minimization procedure. Here, an effective consistency threshold of 0.87 is used, higher than the recommended minimum of 0.75 (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008, 46). This means that the top seven rows are included in the minimization procedure. Notably, this entails all cases that show the outcome (printed in bold in Table 5) and there are no contradictory rows with cases that show the outcome and those that do not as part of the same configuration, which meets an important criterion for the truth table analysis (cf. Rihoux and De Meur, Reference Rihoux, De Meur, Rihoux and Ragin2009).

The third stage of the set-theoretic analysis with QCA is the minimization of the truth table. Based on a Boolean minimization algorithm, the software (the ‘QCA’ package in R, Duşa, Reference Duşa2019) can derive three solution terms, which differ in how they treat logical remainders, resulting in more or less parsimonious or complex solutions. Table 1 displays the intermediate solution term for the outcome military participation in the anti-Daesh different combinations of conditions, which are listed in the left-hand rows. I follow established notation, where black circles (‘⦻’) refer to the presence of a condition and crossed-out circles (‘•’) indicate a condition’s absence. Below each path are listed the measures of fit, including coverage scores. These reflect how much of the empirical data is explained by each path. Moreover, the table lists which countries/cases are covered by which path and which of these are solely accounted for by an individual path (bold font). The lower end of the table details the total solution consistency and coverage, and the number of models derived (a single model). The intermediate solution incorporated four directional expectations, which guide the inclusion of logical remainder rows, namely the presence of an external threat (T), alliance value (A), public threat perception (P), and the absence of parliamentary veto rights (∼V) which were expected to contribute towards the outcome. Because party political incentives can cut both ways, as discussed above, no specific expectations were formulated for this condition. The complete truth table with an indication of which logical remainders were used for the intermediate solution as simplifying assumptions is documented in the online appendix (Table A2).

What do the results tell us about contributions to the anti-Daesh coalition? There are four notable findings. First, it is apparent that all solution paths contain either an external threat (Paths 1 & 2), or alliance value (Path 3), or a combination of these two conditions (Path 1). This underscores the relevance of international-level incentives for coalition contributions – as most of those countries that contributed militarily had foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria (many of these countries also experienced jihadi terrorism on their own soil), and many valued their alliance membership in NATO and their relationship with the USA. Moreover, the analysis documents the utility of a configurational perspective that integrates international- and domestic-level factors (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Lepgold and Unger1997; Haesebrouck, Reference Haesebrouck2018; Massie, Reference Massie2019), because neither external threat nor alliance value are sufficient on their own to bring about the outcome. Throughout the three paths, the two conditions combine with other push factors (Path 1 and Path 2) and with the absence of a constraint against military involvement (Path 2 and Path 3).

Second, the results also show that many of those countries that made meaningful military contributions do not have legislatures with an ex ante veto right over military deployments (parliamentary war powers). Precisely, it is the absence of this institutional constraint that characterizes Path 2 and Path 3 (either in combination with an external threat and public threat perception or together with alliance value, a right executive, and the absence of public threat perception, respectively). This finding broadly resonates with studies that have emphasized the relevance of parliamentary veto power on military deployments (Peters and Wagner, Reference Peters and Wagner2011; Ruys et al., Reference Ruys, Ferro and Haesebrouck2019), but which have also highlighted that there is an interaction between institutional rules, political preferences, and the context of military missions (Wagner, Reference Wagner2018, 131; Mello, Reference Mello2019, 49). Of those that participated militarily, only the legislatures in Germany and Denmark have formal veto rights over military deployments (hence these two countries are uniquely covered by Path 1 instead of Path 2), and Germany limited its involvement to air support, arguably due to political and constitutional considerations, if the parliamentary debates in the Bundestag following upon the terrorist attacks against Charlie Hebdo and the Bataclan are taken as an indicator. Indeed, the German government’s policy on the anti-Daesh coalition seems to reflect the country’s traditional reluctance when it comes to military involvement and warfighting (Brummer and Oppermann, Reference Brummer and Oppermann2016). This contrasts with Denmark, where involvement in US-led military coalitions enjoys broad political support and has become part of the country’s strategic culture (Jakobsen and Rynning, Reference Jakobsen and Rynning2019). These political preferences also help to explain why the institutional rules of formal parliamentary involvement on military deployments did not stop Denmark from engaging in airstrikes against Daesh in Syria and Iraq.

Third, the analysis shows that rightist partisanship was associated with military involvement, which resonates with the direction expected by most of the literature on party politics and security policy (Hofmann and Martill, Reference Hofmann and Martill2021; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2017). Yet, this finding must be qualified because a right executive features in only one of the three solution paths and this combination is solely populated by Poland (Path 3). Moreover, when we examine Table 5, we also see that three countries that were involved in the air strikes did not have right executives (France, Denmark, and Italy). Based on the discussion in the theory section, this is not too surprising, because the anti-Daesh coalition was neither a classic left-of-center military mission, like a humanitarian military intervention (cf. Rathbun, Reference Rathbun2004), nor a purely right-of-center strategic use of force, but a mixture of both types of missions, where clear-cut partisan patterns are less prone to materialize, even though a recent study on EU member states’ involvement in military operations since the late 1990s found that left governments, by-and-large ‘were more inclined to participate’ in these military missions (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020, 579).

Finally, public threat perception is the only condition that appears in two qualitative states in the solution term (presence and absence of the respective condition). However, apart from the case of Poland, public threat perception was present among all of the cases that showed the outcome (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and UK). As such, this pattern resonates with the expectations derived in the theory section. While Poland was considered to be rather outside the set public threat perception, this case contained three conditions that were directed towards military involvement and which thus arguably outweighed the lower level of threat perception.

Drawing on public opinion data from a Special Eurobarometer survey on public perceptions of terrorism and the foreign fighters phenomenon (EC, 2015), this paper has made a first step towards filling a gap that previous studies identified, but which had not yet been addressed with comparative data (Haesebrouck, Reference Haesebrouck2018; Saideman, Reference Saideman2016). That said, public opinion on foreign and security policy, and especially on military missions, is notoriously difficult to measure. This is one reason why many comparative studies have not taken it into account, even though it is often acknowledged as an important factor to consider. To further explore this factor, future work could focus on the development of public opinion throughout the anti-Daesh coalition, among a smaller subset of EU member states, where more fine-grained data might be available. Such an approach was taken, for instance, in a temporal comparison of public support for military involvement during the Afghanistan missions of Canada and Germany throughout the ISAF mission (Lagassé and Mello, Reference Lagassé and Mello2018).

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed military contributions from the EU − 28 to the anti-Daesh coalition in Iraq and Syria. The results of the configurational analysis highlight the importance of external threats and alliance considerations, as well as the policy relevance of institutional constraints, particularly legislative veto rights. Concerning the former, all countries that contributed militarily to the airstrikes did so either under the presence of an external threat, as when some of their own citizens joined Daesh as foreign fighters, or because of alliance considerations. This broadly resonates with expectations formulated in realist-inspired empirical work on state behavior with regard to military coalitions (Davidson, Reference Davidson2014; Pedersen and Reykers, Reference Pedersen and Reykers2020). Yet, it is also clear that domestic factors cannot be disregarded, especially institutional constraints like parliamentary war powers (Peters and Wagner, Reference Peters and Wagner2011; Ruys et al., Reference Ruys, Ferro and Haesebrouck2019). These seem to have posed an effective constraint on executive decision-making, as only two countries with a legislative veto on military deployments, Denmark and Germany, participated in the airstrikes, and the latter restricted its military involvement to air support functions, arguably for political reasons. In Denmark, the broad political support for expeditionary warfare and involvement in US-led coalitions arguably outweighed the institutional constraint posed by mandatory parliamentary involvement.

Clearly, and this appears to be a broader trend beyond operation ‘Inherent Resolve’, governments seek the added legitimacy of parliamentary approval, also in countries where parliament is not formally involved in security policy and where there is no obligation on executives to debate and vote on missions. Among others, this was the case in Belgium and the UK, where involvement in the anti-Daesh coalition was decided upon by parliament (Strong, Reference Strong2018; Fonck et al., Reference Fonck, Haesebrouck and Reykers2019). Notably, partisanship did not yield pronounced patterns. In the light of prior studies’ results, this is not too surprising, because the anti-Daesh coalition did not constitute a traditional left-of-center military mission, as in a humanitarian military intervention, nor was it driven purely by strategic considerations, which the political right would support. Instead, the military coalition was a mixture of both types of missions, where clear-cut partisan patterns should not be expected. However, as Hofmann and Martill (Reference Hofmann and Martill2021, 322) acknowledge in a recent review, ‘party politics is more variegated in its effects than we might wish to accept’. Hence, the failure to detect clear-cut patterns of partisanship should not be taken to imply that party politics did not matter for decision-making during the anti-Daesh coalition.

With its focus on providing a European comparison of military contributions and a framework of five international- and domestic-level factors, it was beyond the scope of this paper to explore the multidimensional nature of the fight against Daesh. Prospective studies could complement this with a comparison of humanitarian aid and capacity-building efforts in the region. Moreover, emphasis could be placed on the human security dimension of the airstrikes, investigating the conditions under which civilian deaths occurred and comparing the accountability mechanisms of the involved countries. Footnote 20 Finally, another aspect that deserves a focused treatment is the time dimension, taking into account the entry and exit of various allies throughout the military campaign, as we know that coalition withdrawal often occurs as a function of domestic politics. Recent studies have covered this at the individual case level, for instance for the war in Iraq (McInnis, Reference McInnis2019; Mello, Reference Mello2020). Here, it would be worthwhile to explore whether similar dynamics also occurred during the coalition against Daesh. Finally, as mentioned at the outset of this paper, the anti-Daesh coalition received support from more than 70 states and five international organizations. Future studies could explore the involvement of other groups of countries, for instance in the MENA region and sub-Saharan Africa, also with focused comparisons between democracies and non-democracies among those involved in the coalition.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000333.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Amos Fox, James Rogers, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. For research assistance during the initial stages, I am grateful to Danielle Al-Qassir and Teslin Augustine.