The International Review of the Red Cross occupies a unique position in the world of academic publications. First, of course, is its long history: 2019 marks the Review’s 150th anniversary, making it one of the oldest periodicals in the world to be published continuously.Footnote 1 The complete collection, including the Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, Russian and Turkish versions, fills nearly 12 meters of library shelves. The Review has published 23,686 articles covering more than 110,000 pages.

Another standout feature is the journal's editorial line: the Review has always been driven by the humanitarian imperative of the founders of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement). The changing nature of crises has constantly challenged humanitarian thinkers to come up with practical new solutions, be they of a political or a legal nature. Throughout its history, the Review has had the distinction of driving this debate forward at all levels, from practice to theory to policy – in other words, from the battlefield to the drawing board and then the negotiating table.

The Review has a rich history, and that is the focus of this issue.Footnote 2 The journal offers a unique perspective on the history of the Movement and the humanitarian sector more broadly, but also on that of contemporary conflicts and crises. From the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 to the ongoing war in Syria (the focus of our last issue), the Review’s archives offer insights into 150 years of tragedies, shortcomings and progress, written by visionary pioneers, inspired amateurs and seasoned experts – modern humanitarians all.

This anniversary issue of the Review gave the editorial team a chance to invite researchers to explore these various dimensions. It is also an opportunity for me to discuss my own experience with the Review since I joined it in 2010, my passion for this journal, the editorial decisions we have made, and the topics we will address in the coming years.

Expanding, informing and professionalizing through 150 years of humanitarian writing

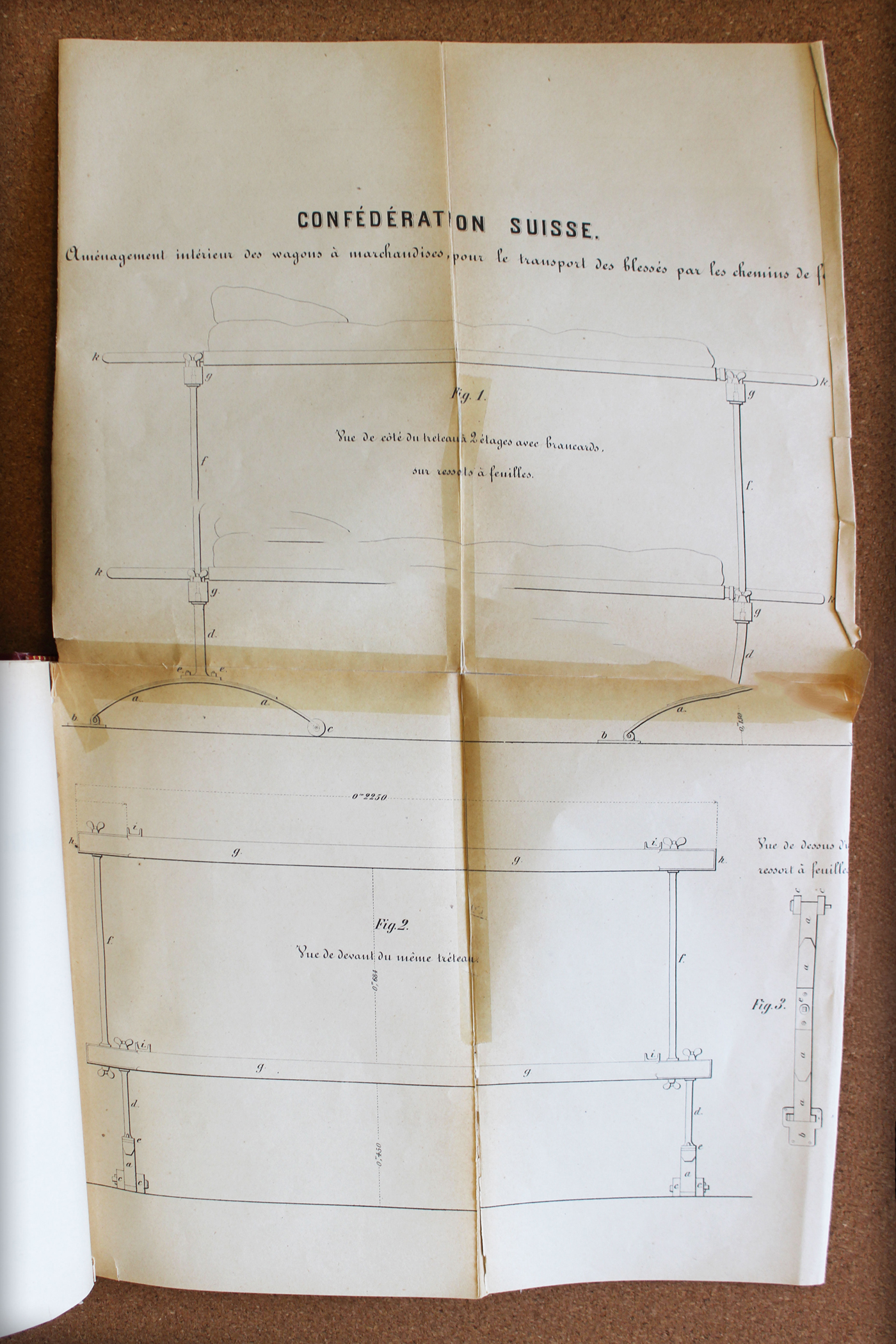

The Review is by far the oldest publication in the humanitarian sector. This is no minor detail. For me, the journal's longevity is a tribute to the perseverance and tireless humanitarian commitment of successive generations of men and women who have used it as a platform for sharing their thinking, their new ideas and their experiences. On these pages, you can ponder technical drawings of the first-ever field ambulances,Footnote 3 treatises on war medicine, and proposals – whether visionary or utopian – on ways to limit human suffering in times of crisis. The Review’s staying power stems from a humanitarian commitment that turns its history into a narrative.

The Review’s content and layout have changed radically over the past 150 years. The journal helped to construct the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Movement, simultaneously or by turns; it has served as a forum for launching – and a vector for spreading – new ideas; and it has played a role in professionalizing humanitarian work.

The Review can trace its origins to the Second International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, which took place in Berlin in 1869. Originally entitled the Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés (International Bulletin of Relief Societies for Wounded Soldiers), the publication had a crucial function: it was to deliver news and information for the fast-growing Movement. As British medical reformer John Furley noted in 1869, the Bulletin was the Movement's fountainhead, the place where people could find out more about common challenges.Footnote 4 Its pages offered solutions to some of the earliest problems dealt with by National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (National Societies): how should wounded soldiers be transported from the battlefield to the hospital? How should first aid be administered to wounded soldiers on the battlefield? The first few issues of the Bulletin contain technical drawings of wheeled stretchers and suspended beds for rail cars – I find these examples particularly moving, during this period of creative fervour, this humanitarian big bang.

At a time when National Societies were being formed all over the world, the Bulletin published wonderful engravings of stretchers made from bamboo, fitted to camels or even mounted on skis. The scope of humanitarian action quickly expanded beyond caring for the war-wounded to include an ever-growing number of needs.

The ICRC did not have extensive field operations at the time. Rather, it served as the Movement's international secretariat and encouraged States to create a body of law to protect war victims. The Bulletin was the preferred communication platform for the ICRC and its second president, Gustave Moynier, whose writings reflect his political and organizational talents. David Forsythe and Daniel Palmieri's articles in this issue clearly demonstrate that for the Review’s first 100 years, the ICRC employed it as a strategic tool in its relationship with the Movement.

Figure 1. Technical drawing of wheeled stretchers and suspended beds for rail cars. Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1870.

The Review traces the gradual expansion of humanitarian action, first by the Movement and then by the humanitarian sector more broadly. But in some cases what the Review does not say speaks to the ICRC's failures, extreme caution and blindness to what was really happening in the world. In certain eras, we can detect biases towards this or that warring party – belying the principle of neutrality – or an overly restrictive interpretation of the ICRC's mandate. And in some instances, the journal's pages harbour colonialist prejudices, which are diametrically opposed to the current meaning of the word “humanitarian”.Footnote 5

The ICRC greatly expanded its activities after the First World War broke out, and, in 1919, the section of the Bulletin that described its work in detail filled out and became the Review. The Bulletin, whose purpose was to report on the doings of the National Societies, was published into the 1950s, now as a subsection of the larger Review. Over time, the Movement's activities grew to such an extent that they could no longer be encapsulated in a print publication. The Review therefore gradually changed its focus: it served first as a platform for spreading knowledge of international humanitarian law (IHL) and the ICRC's views on humanitarian issues, and it then became an academic publication.

In addition to documenting the blossoming of the humanitarian sector, the Review has also been an incubator for new ideas over the years, particularly in the realm of IHL and humanitarian principles. Beginning with the first Geneva Convention, which was adopted in 1864, IHL as a body of law expanded as the years passed through a series of conventions. The Review published the first plan for a permanent international criminal court a full 130 years before the Rome Statute took effect and the International Criminal Court was created in The Hague.Footnote 6 The journal was also used to inform the warring parties of the ICRC's stance against the use of combat gases in the First World War.Footnote 7 As well, the Movement's Fundamental Principles, which form the basis of today's humanitarian action, were unveiled on these pages by their author, Jean Pictet.Footnote 8

The 1960s and 1970s were marked by a series of conflicts fuelled by decolonization and the Cold War. The horrors of modern war were embodied in the photo of a little Vietnamese girl, naked and terrorized, her arms outstretched and her back burned by napalm.Footnote 9 Images of violence raced around a restless world yearning for change – whether peaceful or violent in nature – and buffeted by competing societal models. This was also a period in which IHL was further developed and codified, with the adoption of the Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions in 1977. At the same time, the humanitarian sector diversified and grew in size – a process that continues to this day. The idea of raising awareness of humanitarian rules and principles gained renewed impetus. Beyond its role in the Movement, the Review was one tactic in the ICRC's effort to forestall violations of IHL and get its message through to a network of influential people in universities, governments and the military.

The Review was instrumental in instructing people about IHL via a legal positivist lens. As an international law student in the 1990s, it was surely from these pages that I picked up most of my early knowledge of IHL. But while the Review continues to provide such information, many other sources, such as manuals and online courses, fortunately exist today. Thanks in part to the ICRC's efforts, IHL is taught much more widely in universities now than in the past.

It is striking that the humanitarian sector is adopting an increasingly evidence-based approach to its decisions and strategies. As one of the rare academic journals to publish the work of humanitarian researchers, the Review also contributes to the growing professionalism of the Movement and of the humanitarian sector as a whole.

“Humanitarian professionalism” – now that's an ambiguous expression. For many years, describing humanitarian work as a job did not comport with its view as a charitable calling. That's because humanitarian workers were, by definition, “amateurs” (according to this word's etymology: “someone who loves”). Humanitarian organizations have always hired specialists (surgeons, logistics experts, lawyers, and so on), but being a “humanitarian” was never considered a job or a career – no more than being a “revolutionary” or a “missionary” was. In recent decades, however, the increase in the number and size of humanitarian organizations and the emergence of specialized degree programmes has resulted in the emergence of a humanitarian sector. Starting in the 1990s, significant improvements have been made in staff training, quality standards and transparency – alongside a growing bureaucracy.

It would therefore be tempting to view humanitarian work as any old field of work. Yet just as 150 years of experience show that aiding victims of conflict takes more than “good intentions”, humanitarian work cannot be reduced to a toolkit of methods borrowed from governments or multinational corporations. Human dignity cannot be reduced to a product or an algorithm.

In its articles, the Review seeks to distil the essence of humanitarian professionalism.

Our editorial line over the years

The second way in which the Review stands apart among academic publications is its editorial line. This is built on three pillars: (1) analysis of humanitarian topics or crisis situations, (2) the humanitarian response and its associated challenges, and (3) legal solutions.

By focusing on specific topics and juxtaposing multiple points of view, we aim to anchor humanitarian action and the further development of IHL in hard reality. Each issue has one topic, and the articles are carefully selected: we parse out the aspects of each topic and then seek the most qualified contributors.

The earliest issues contained a preponderance of articles on medical topics and relayed news of the Movement and its operations. Topics of humanitarian policy and law have gradually taken the upper hand. Today, the Review serves up a unique array of articles in the human and social sciences – law, the military, history, international relations and political science – as they relate to conflict.

Most humanitarian challenges are, alas, recurrent: the Review has devoted several issues to missing persons, nuclear weapons and forced displacement, for example. Revisiting these topics provides an opportunity to gauge progress and come up with new solutions. It is also striking to note that the terms of humanitarian debates tend to recur with each successive crisis. Depending on the types of crises faced by humanitarian organizations, some questions come up regularly, such as the link between development and humanitarian action and the use of aid as a political tool by governments or armed groups.

In the area of new technologies, the terms of the debate were already set out in the nineteenth century. Some people want to prohibit the use of new technology and new weapons, others would like to regulate their use, and a handful feel that these inventions will miraculously lead to full compliance with the law – for example, Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, perhaps surprisingly thought that the development of more powerful weapons would help usher in universal peace. Those actually working in the humanitarian sphere seek ways to shield themselves from these technological advances – or to somehow harness them in their aid work. After all, modern humanitarianism emerged alongside the industrial revolution and a belief in the power of science. The Review itself is a product of this ambition to combine “charity” with scientific rigour.

It is thus striking to note that the race to “progress” (or to “innovate”, in today's lingo) which accompanied the development of humanitarian action in the nineteenth century was a necessary response to a string of crises and the immutable nature of the most basic humanitarian problems and war crimes. We are still seeing wounded people and medical workers and facilities coming under attack in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria – as if Henry Dunant's core tenet needed to be reinvented. Françoise Bouchet-Saulnier, who works at Médecins Sans Frontières and is a member of the Review’s Editorial Board, terms this a return to the pre-Solferino world.Footnote 10

In the humanitarian debate, the Review, with its historical perspective, has a duty to identify signs of progress (moving forward by drawing on past experience) and avoid the trap of change (throwing out and starting again). The next hot thing, platitudes and empty neologisms – as meaningless as they are fleeting – now afflict a flourishing humanitarian sector filled with organizations competing for power and funding.

The Review and the ICRC

The Review’s mission is to promote reflection on humanitarian law, policy and action in armed conflict and other situations of collective armed violence. A specialized journal in humanitarian law, it endeavours to promote knowledge, critical analysis and development of the law, and to contribute to the prevention of violations of rules protecting fundamental rights and values. This publication has always been supported by the ICRC, which finances it, translates it and distributes it around the world. While it was once the organization's official journal, publishing appointments, legal views and operational reports, the Review has evolved and is now an academic publication put out by Cambridge University Press and featuring articles from a wide range of sources.

Today the Review continues to help shape the debate over the humanitarian implications of new weapons and new loci of humanitarian work. Its articles are intended to influence not just researchers but also international tribunals, government decision-makers and military legal advisers on today's battlefields.

Thanks to its links with the ICRC, the Review can (1) tap into the organization's extensive field experience and benefit from its footprint in today's war zones, thereby buttressing the publication's relevance and credibility; (2) draw on the ICRC's global network of delegations, which can translate and promote the Review; and (3) propose constructive solutions to humanitarian problems through an approach based on information-sharing and prevention, on one hand, and planning and preparations, on the other.

The Review continues to publish experts’ views on topics such as detention, IHL and relations with armed groups. Among the most influential pieces on IHL that we have run, we would mention Sylvain Vité’s article on the typology of conflicts,Footnote 11 Marco Sassòli and Laura M. Olson's article on the relationship between IHL and human rights law,Footnote 12 and Cordula Droege's article on the applicability of IHL to cyber warfare.Footnote 13 Not only ICRC staff but also academics and other humanitarian practitioners have published articles that have driven the debate forward. These include Daniel Bar-Tal, Lily Chernyak-Hai, Noa Schori and Ayelet Gundar on perceptions of victimhood in protracted conflicts,Footnote 14 Beth Ferris on faith-based and secular humanitarian organizations,Footnote 15 and Peter Asaro on autonomous weapon systems.Footnote 16

Yet the ICRC's extensive field operations impose an important editorial constraint on the Review: at times, when discussing a highly sensitive topic for a party with which the ICRC is engaged in an operational dialogue, we must tread softly. The Review is thus confronted with the classic dilemma faced by many on-the-ground organizations: do we take a public stance at the risk of losing access to our beneficiaries?

While the Review benefits from this relationship, it is also clearly in the ICRC's interest to support this platform, where competing views can be expressed in accordance with the principle of academic freedom – whether or not the writers have links with the ICRC. The Review is still a breeding ground for new ideas. As Marko Milanovic noted in a blog post on EJIL: Talk!,Footnote 17 when ICRC experts write for the Review, the work they put in often refines their views, which then result in official ICRC positions.

Still, the disclaimer that accompanies most of the articles must not be discounted: the opinions expressed in the Review do not necessarily reflect those of the ICRC. In fact, the ICRC sometimes uses the journal as a way to test new ideas. It then adapts them based on the feedback it receives from academics, governments and others.

Apart from its ties to the ICRC, the Review has been profoundly influenced by its successive editors-in-chief, starting with Gustave Moynier, the publication's creator. The journal has had sixteen editors-in-chief so far, with quite diverse professional backgrounds:Footnote 18 some were legal experts or journalists, but there was also a chemist, a pastor, a colonel and a poet. For this issue, we asked three former editors-in-chief to share their views on how the journal has changed over the years.Footnote 19

Today's Review

The journal's current editorial team seeks to maximize the range of views expressed and foster debate; expand the journal's readership and influence; and stimulate research into solutions that will promote acceptance of humanitarian action and IHL.Footnote 20 In recent years, our quest for diversity has translated into an active search for writers (and readers) all over the world. For every topic, we have sought out the best writers, travelling and holding conferences far and wide – from Washington, DC to Beijing, and from St Petersburg to Abidjan.Footnote 21 The Review solicits contributions from theorists and practitioners, but we also make an effort to let those who are helped by the ICRC have their say too. In the future, we hope to publish more articles from aid workers themselves, on their experience in crisis situations.

We make a systematic effort to strike a balance between the sexes, nationalities, perspectives and disciplines. We still have our work cut out for us in terms of geographical diversity, as most of our writers are European, North American or Australian. We do not publish enough articles from writers in Africa and Asia, despite the fact that these regions are affected the most by conflict.Footnote 22

Our insistence on debate and diversity is underpinned by an active Editorial Board, which is composed of non-ICRC experts. Selected for both their expertise and their enthusiasm, they meet every year in order to help the Review’s editorial team choose its topics and promote the journal. They also contribute articles.Footnote 23

We have also laboured to bring the Review out of its relative isolation within the ICRC – today the journal enjoys the active support of the ICRC's Department of International Law and Policy.Footnote 24 Furthermore, we have sought to increase the journal's online circulation, including through a blog.Footnote 25

Beyond questions of circulation and influence, however, we believe it is important to share our constructive and solution-oriented approach and to capitalize on our network of academic experts. Our team has conducted research into IHL success stories and the positive impact of compliance with IHLFootnote 26 as a way of demonstrating its relevance in ongoing conflicts, and we hope to encourage the adoption of this approach.

The Review’s topics in 2019 and 2020 include the following: memory and war, children and war, protracted conflicts, digital technology, war and the body, war and the mind, the Sahel, terror and counterterror, the development of IHL, and emotions and war.

***

Ten years, twenty years, fifty years, 100 years and 125 years: the Review has already published a number of anniversary issues and articles. “For a periodical devoted to such a narrow specialty to last this long without interruption, through times of peace and war, is irrefutable evidence of the Red Cross's vitality and sustained activity.”Footnote 27 This quote conveys the wonder felt by the author of an article titled “The Past and the Future of the International Bulletin”, framing the tenth anniversary of the Bulletin as quite the milestone.

Some, however, might see evidence of failure in the Review’s longevity. Shouldn't all this effort have been devoted to preventing wars rather than trying to reduce their horror? The editorial in the very first issue, in 1869, refutes this criticism: “until the friends of peace emerge victorious, wisdom advises remaining prepared for any event”. There's still a place for humanitarian journals in today's world.

For this anniversary, the Review team is creating a new website that will make it easier for people to consult past issues. In fact, open access will now be provided to the entire digitized collection. Once the collection has been uploaded, researchers will be able to dig deeper into the history of humanitarian law, policy and action through the Review.

From this history – the study of which is still in its early stages – I would like to already draw one lesson. The protections accorded to victims have always advanced not linearly but in fits and starts, depending on the international climate. Yet this process has been punctuated by long periods of stagnation, paralysis, or even backsliding by international governance.Footnote 28 Still, the history of the Review shows that the progress that has been achieved is in no way accidental. Those who have been directly affected by war, researchers, legal experts, academics and government experts have always played a crucial role, tirelessly identifying new threats, coming up with and sharing solutions, and laying the groundwork for the next step forward by IHL. They have seized every opportunity they could to curb egotism and the sense that might is right. We need their contributions now more than ever.