“The whole of history must be studied anew!”

Friedrich Engels (1890)Footnote 1

Marx is considered to be the (co-)founder of the so-called “materialist conception of history”; he did not use the term “historical materialism”. It is impossible to outline such a “theory of history” – or, more precisely, a theory of the “world historical process” – without a detailed study of history, without a precise knowledge of the immense, chaotic mass of “facts”, of documents, of all kinds of rediscovered lost materials, of traditions, of written (and thus already interpreted) history. For the social sciences, the whole history of humanity is subject matter – and at the same time material. Every social science is therefore a “historical and social” science. In the fragmentary manuscript, the German Ideology the following is stated briefly, programmatically (and ambiguously): “We know only a single science, the science of history.”Footnote 2 Neither Marx, nor Engels “ever departed […] in substance” from this early position.Footnote 3

Marx Studies World History

Once more, in 1880, Marx formulated his theoretical intention: he wanted to “prepare the way for the critical and materialist socialism, which alone can render the real, historical development of social production intelligible”.Footnote 4 Marx never departed from this idea. The aim was and always remained giving the socialist movement a solid, social-scientific foundation instead of a political philosophy.

Shortly afterwards, during 1881/1882, Marx filled four notebooks full of excerpts on the course of world history.Footnote 5 There are four notebooks or writing books in the German standardized A5 format, with attached marble cardboard covers and black-cloth binding, pages are ruled with narrow blue lines. Engels provided the notebooks with titles written by hand on rectangular affixed labels:

Chronological Extracts I, 96 to approximately 1320

Chronological Extracts II, approximately 1300 to about 1470

Chronological Extracts III, approximately 1470 to 1580

Chronological Extracts IV, approximately 1580 to approximately 1648

Preserved in the Marx-Engels-Nachlass at the Amsterdam International Institute of Social History,Footnote 6 the four notebooks are in Marx’s handwriting (written with a sharp quill [Feder] and thus relatively readable). The excerpts and occasional comments are characteristic of his way of working. He wrote in a mixture of languages, the notebooks consisting predominantly of German with English, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish and even some Russian. The majority of these excerpts and notes remain unpublished, but they are meant to appear in the fourth section of the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (henceforth: MEGA2) (Volume IV/29).

These excerpts are about the works of two contemporary historians: the Histoire des peuples d’Italie by Carlo Guiseppe Guglielmo Botta, published in Paris in three volumes in 1825, and the Weltgeschichte für das deutsche Volk by Friedrich Christoph Schlosser, initially published in six volumes and eventually in eighteen volumes between 1844 and 1857 in Frankfurt am Main. The first notebook contains extracts from Botta’s book, the following three notebooks extracts from Schlosser’s work. Among German historians, Schlosser was a very successful author, working since 1817 as professor of history at the University of Heidelberg. With the nine-volume Weltgeschichte in zusammenhängender Erzählung that appeared between 1815 and 1824 in Frankfurt am Main, Schlosser began his ambitious attempt at a complete overview of all known historical facts. The eighteen-volume version of his world history, available until shortly before World War I in Germany, had a total of twenty-seven editions and was compiled from his early work and lectures, for the most part, by his student Georg Ludwig Kriegk.Footnote 7 Arguably, as someone who accurately followed German scholarly literature, Marx was aware that he was dealing with the star historian of his period – Schlosser, a scholar who revered a quite idealistic conception of history in which morals and ideas played a prominent role, and a writer who did not shy away from harsh subjective valuations.Footnote 8 Marx knew and used Schlosser’s work prior to producing the Chronological Extracts. This can be seen firstly by a short and friendly reference to Schlosser in Marx’s preparatory studies to the chapter on Dühring’s Kritische Geschichte der Nationalökonomie und Sozialismus, which Engels adopted in his Anti-Dühring. Reacting to Dühring’s arrogant, condescending remarks on David Hume, Marx referred in his notes to “the honest old Schlosser who was enthusiastic about Hume”. The second instance can be seen in a later draft of the chapter, where Marx stated what “the good old Schlosser” had to say about Hume.Footnote 9 Hence, Marx could write in a text intended for a German audience – an audience that was not, or only partly, academic – about a well-known and most likely renowned personality. Schlosser, the author of a widely read and respected “house book”, was well known to the educated classes and all those thirsting for knowledge.

Botta, who studied medicine and had practised as a military surgeon, a decided supporter of the French Revolution and later Bonapartist, wrote a history of the American War of Independence and various works on Italian history. The first of his works on Italian history, the Storia d’Italia dal 1798 al 1814 (Paris 1824) appeared in five volumes, then the Histoire des peuples d’Italie, which Marx excerpted, and subsequently the ten-volume Storia d’Italia continuata da quella del Guicciardini dall 1534 sino al 1789 (Paris 1832). The copy of Botta’s Histoire des peuples d’Italie found in Marx’s library contains extensive marginalia.Footnote 10 It is now clear that Marx possessed a copy of Schlosser’s Weltgeschichte for use at home. Marx’s library or “probably Marx’s library”, as it is called in the annotated catalogue of identified inventory, also contained Schlosser’s Weltgeschichte für das deutsche Volk, and indeed the six-volume edition in the second unaltered printing that appeared in Frankfurt am Main from 1846–1848.Footnote 11 Moreover, Marx seems to have inherited the nineteen volumes of Schlosser’s Weltgeschichte from his late friend Wilhelm Wolff in 1864.Footnote 12

In the 1950s, Wolfgang Harich created a collection of classic texts on German history – Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin were the classics. The fourth volume of Harich’s edition contains selected passages from Marx’s Schlosser excerpts, mainly from the fourth notebook concentrating on “German History”.Footnote 13 These selected passages from Marx’s excerpts (from notebooks III and IV), comprising somewhat less than a sixth of the entirety, are about events and figures in the German history of the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth centuries. They concern politics and power struggles, the rise and fall of major and minor rulers, as well as major and minor actions of state. Legislation, administration, major and minor reforms, war, peace, trade, and the rise and downfall of dynasties also come into focus, as does the foundation, rise, and dissolution of states and empires. Marx covers diplomacy, treaties, key documents, religion, and, above all, the Church as a worldly political power, the Reformation, and the Counter-Reformation. In Marx’s own words, the selected passages concern the “struggle between capital and king”. In sum, they are about the long and entangled process of state formation in Europe.Footnote 14 Even if Marx occasionally, by means of references and parenthesis, points to later developments or prior or previous events, these extracts are clearly structured and chronologically ordered. In these published parts from Harich’s edition there are only a few comments by Marx’s hand. Marx occasionally corrects Schlosser’s factual errors. Where Marx did comment, he either summarized long complex developments (for example, economically relevant and serious political developments, economic facts that he regarded as presuppositions for further political developments, or background political conflicts) or he pointed to single events, highlighting and interpreting them in his own way.

Marx’s Historical Studies – from 1843 to 1882Footnote 15

The Schlosser excerpts are only the last in a long list of preliminary studies and studies on the course of world history that Marx pursued from 1843 until the final years of his life. These studies – which faute de mieux we call “historical” – are closely connected with the development of his economic studies. Marx’s comprehensive studies of both European and non-European history, and indeed of the whole of history, from political, legal, economic and social history to cultural history, as well as the history of technology and the sciences, form the foundation from which he constructed his political economic analyses of modern capitalism.

At the Gymnasium in Trier, Marx enjoyed good history lessons. In Bonn and in Berlin, he studied jurisprudence and heard numerous lectures on Roman, mediaeval and modern legal history. As a young journalist, Marx quickly discerned that his knowledge of economic and social facts was not sufficient to participate in any serious debates on current economic affairs. He attempted to remedy this shortcoming through avid study. Marx was self-taught in economic and social history, as in political economy. In legal history, however, this was not the case. Marx’s university studies are only documented in a fragmentary way – few excerpts that he produced during his student days have been preserved. Whereas the excerpts on art history survive, those on legal history and other topics are missing.Footnote 16 Marx began the study of political economy in winter 1843/1844, grappling with the great theoreticians of the French and English schools first. He only knew the latter from Hegel’s writings or by name: Say, Smith, Ricardo, MacCulloch, and, last but not least, Friedrich Engels. In September 1846, he subsequently began to study and excerpt Gustav von Gülich’s monumental economic history, the Geschichtliche Darstellung des Handels, der Gewerbe und des Ackerbaus der bedeutendsten handeltreibenden Staaten that appeared in Jena from 1830 to 1845 in five volumes. Gülich’s book was a standard work in Marx’s time, all educated people read and used it – including the privy councillor Goethe in Weimar.Footnote 17 Marx keenly pursued his independent study of economic, financial, and social history from September to December 1847. Having Gülich always at hand gave him a reliable foundation from which he could continue to work.Footnote 18

Marx repeatedly delved into the study of political history both before this period as well as after, initially with the study of modern French history in Kreuznach and in Paris. Before abandoning the plan to write a “history of the national convention” in Kreuznach, from July 1843 onwards he was essentially occupied with the history of France and other European countries.Footnote 19 It is no coincidence that Marx had recourse to the prevalent and widely lauded standard work of the period: the voluminous Geschichte der europäischen Staaten, edited from 1819 until 1830 by the Göttingen professor of history Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren and the Gotha geographer Friedrich August Ukert. From this collection, Marx studied the Geschichte von Frankreich by Alexander Schmidt, the Geschichte Schwedens by Erik Geijer, the Geschichte von England by Johann Martin Lappenberg, the Geschichte Frankreichs im Revolutionszeitalter by Wilhelm Wachsmuth, and the Geschichte der Teutschen by Johann Christian Pfister. Furthermore, there were books and writings on French, English, Polish, and German history, even a short excerpt from Pierre Darus’s Histoire de la république de Venise. Footnote 20

In the 1850s, in London exile, Marx took up his historical studies once again. Excerpts from the writings of English and French economists predominate in the London Notebooks that originate in 1850 and continue until 1853. Marx, however, also deepened his knowledge of the history of money by studying several older and some more recent works on the subject: in particular, Germain Garnier’s 1819 Histoire de la monnaie, a standard work of the time, as well as William Jacobs 1831 book on the history of precious metals and other writings by these authors on agrarian history. Marx intensively studied the 1817 four-volume work by the classicist August Böckh, Die Staatshaushaltung der Athener, as well as two larger works of the then leading German economic historian Johann Georg Büsch: his history of money and finance and his history of trade. Additionally, Marx analysed an entire set of English authors on the history of state debt in England and on the English banking system.Footnote 21 Furthermore, Marx continued to read and excerpt Heeren’s books: his Handbuch der Geschichte des Europäischen Staatensystems und seiner Colonien, using the third edition that appeared in Göttingen in 1819 and his Ideen über die Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der alten Völker. From the latter, Marx only excerpted the first part on Asian nations.Footnote 22 At the same time, Marx studied an entire set of English works on colonial history. In 1851, he discovered the Bonn historian Karl Dietrich Hüllmann, and read and excerpted his Städtewesen des Mittelalters (four volumes 1826–1829), Geschichte des Ursprungs der Stände in Deutschland (three volumes 1806–1808), and Deutsche Finanzgeschichte des Mittelalters (1805).Footnote 23

Additional excerpts on universal history followed in 1852: from Wilhelm Wachsmuth’s Allgemeiner Culturgeschichte from 1850–1852 and his Europäischer Sittengeschichte from 1831–1839 as well as a short excerpt from Gustav Klemms Allgemeiner Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit from 1842–1853 and once more a short excerpt from the third volume of Heeren’s De la politique et du commerce des peuples de l’antiquité (the French edition of Heeren’s Ideen über Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der vornehmsten Volker der alten Welt first published in 1793–1796).Footnote 24 In the following years, Marx studied Indian history, reading and excerpting Robert Patton’s The Principles of Asiatic Monarchies from 1801 and picked up Wachsmuth’s Europäische Sittengeschichte once more.Footnote 25 Marx also conducted extensive studies on the history of Spain for his series of articles on the actual events in Spain.Footnote 26

Between September 1853 and July 1854, Marx produced four notebooks of excerpts that show an extensive preoccupation with diplomacy, in other words with foreign politics or the relationships between the European states.Footnote 27 Once again, Marx took a standard work in hand, namely Georg Friedrich von Martens’s Grundriss einer diplomatischen Geschichte der europäischen Staatshändel und Friedensschlüsse seit dem Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts bis zum Frieden von Amiens from 1807. The main work of Martens, who as professor for natural and international law in Göttingen founded the modern “positive” science of international law, was Recueil des principaux traité d’Alliances, de Paix, de Trêve, de Neutralité (started 1791 and continued with numerous amendments). Marx arguably knew and used this work, but only made short excerpts from it. Marx’s long excerpt from Martens’s Grundriss was about the history of the wars and conflicts between European states from 1477 until the middle of the eighteenth century. Particularly essential for Marx, as can be seen in his detailed extracts, were the great peace treaties: the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the Peace of Ryswijk of 1687, the Peace of Utrecht of 1713, the Treaty of Vienna of 1738 and, finally, the Treaty of Aachen of 1748, which put an end to the Austrian War of Succession. Repeatedly, Marx wrote short comprehensive reviews on “the state of Europe”, that is on the actual state of the European states system at certain points in time (the end of the fifteenth century and around the years 1600, 1660, 1700, and 1740). For him, this was obviously a way to pinpoint the broad lines of development of major European politics, among the protagonists involved, as well as of the development of individual states and their changing alliances. As a matter of course, he counted Russia and the Ottoman Empire among the big actors of European politics.Footnote 28

For the first time, excerpts comparable to those Marx did of Schlosser’s work are to be found in one of the following books of notes and excerpts of the 1850s. Beginning in 1854 and continuing in the subsequent years, in these notebooks Marx chronologically ordered extracts from Gustav Struve’s nine-volume Weltgeschichte, which appeared between 1853 and 1864. The extracts are short, only six pages in Marx’s handwriting, but extremely succinct, covering the period 1133–1806. Only a few points concerning main political events are recorded.Footnote 29

In 1856, Marx for the first time read and excerpted a work of Friedrich Christoph Schlosser, his Geschichte des 18. und des 19. Jahrhunderts – and indeed from the English translation, which had appeared in eight volumes between 1843 and 1852. The excerpt is relatively short – only ten handwritten pages – with only a few main events from the period Schlosser described recorded in concise headings.Footnote 30 In the same book of excerpts, there are more notes and extracts on the history of England, Russia, the northern countries and peoples. Marx extends these studies to the history of Austria-Hungary and to the countries of the Danube region,Footnote 31 with additional extracts on Russian, Swedish, British, French, and, once again, English history. In the 1857 notebook, there is another short note on Schlosser – Marx recorded his judgement on the historical role of Napoleon – and an excerpt from Johann Georg August Wirth’s Geschichte der Deutschen (1842–1845, four volumes).Footnote 32

In 1860–1861, Marx returned to his study of English, Polish, and Russian history. A relatively long excerpt entitled “Chronicle of the History of European States”, at least twenty pages in length, can be found in the same book of excerpts. This short chronicle is comprised of major events occurring during the period between 1510 and 1856. The main source appears to be Heeren’s Geschichte des Europäischen Staatensystems und seiner Kolonien from 1809 (the 1830 fifth edition).Footnote 33 Marx did not take up his historical studies again until 1868–1869, when he had, after the publication of volume I of Capital, resumed his work on his unfinished economic manuscripts. It is quite remarkable that he simultaneously immersed himself again in studies of the history of property ownership and actually discovered a new authority in the field. Together with Engels, he stumbled upon the works of Georg von Maurer. The jurist and legal historian Georg Ludwig Konrad von Maurer, who taught in Munich, became for him the most important authority for the study of the history of the relationships of landed property ownership in Germany. In the winter of 1868/1869, Marx began with Maurer’s Einleitung zur Geschichte der Mark-, Hof-, Dorf- und Stadt-Verfassung und öffentlichen Gewalt from 1854 and then continued the work in his subsequent notebooks.Footnote 34 In 1869, Hausner’s 1865 Vergleichende Statistik von Europa came into Marx’s hands again. He made comprehensive extracts (over sixty pages in his tiny handwriting); at the same time, he continued his studies of Ireland.Footnote 35 In the following years, quite intensively from 1875 to 1888, he made another great endeavour: filling several books of excerpts on Russian history, especially Russian agrarian history. Marx studied three substantial works, one after the other, by the Bonn professor of history Karl Dietrich Hüllmann: from his 1839 Handelsgeschichte der Griechen, the 1808 Geschichte des byzantinischen Handels, and the 1805 Deutsche Finanzgeschichte des Mittelalters. These extracts fill an entire notebook.Footnote 36 His copious excerpts from Maurer’s Geschichte der Markverfassung and his Geschichte der Fronhöfe, der Bauerhöfe und der Hofverfassung in Deutschland from 1862/1863 almost fill three notebooks completely.Footnote 37 Immediately afterwards, Marx threw himself into the study of another work, the Spanish jurist, publicist, and conservative politician Francisco Cárdenas y Espejo’s Ensayo sobre la Historia de la Propriedad territorial en España, which had appeared in two volumes in Madrid – in 1873 and 1875 respectively. The Cárdenas excerpt – written in a mixture of German, English, and Spanish – is also long, comprising two and a half notebooks.Footnote 38 What Marx was mainly interested in was Cárdenas’s account of the institutions of Spanish feudalism, which developed over a centuries-long conflict against the kingdoms of the Moors through a long series of violent land appropriations and redistributions of (re-) conquered lands. In the same period, he studied additional writings on the history of the Russian agrarian constitution, on Anglo-Saxon law, and returned two more times to Hüllmann’s Deutsche Finanzgeschichte.Footnote 39 Following up on his excerpts from Cárdenas in 1878, Marx read and excerpted the book of the Italian jurist (and politician) Stefano Jacini La Proprietà Fondiaria e le Popolazioni Agricoli in Lombardia from 1856.Footnote 40

In order to deepen his knowledge of the history of Rome in antiquity, Marx made a renewed attempt in the years 1879 and 1880. This time, he studied the works of several German authors, analysing the first book of the economist Karl Wilhelm Bücher Die Aufstände der unfreien Arbeiter 143–123 v. Chr. published in Frankfurt am Main in 1874 and Ludwig Friedländer’s Darstellung aus der Sittengeschichte Roms in der Zeit von August bis zum Ausgang der Antonine, appearing in three volumes between 1862 and 1871. Marx made the longest and most detailed notes and excerpts from Ludwig Lange’s three-volume work Römische Altertümer, the first volume of which appeared in Berlin in 1856. Finally, he read and excerpted the monumental two-volume work of Rudolf von Jhering: Geist des römischen Rechts auf den verschiedenen Stufen seiner Entwicklung published in Leipzig in 1852–1854. These excerpts and notes on Roman history are quite extensive (forty-six scribbled pages). They are in a notebook that still contains substantially more records based upon his readings of various sources: on the history of India, Algeria, and Central and South America.Footnote 41 The authors that Marx read were recognized in their time as important ancient historians or jurists. Jhering was a key representative of the Historical School of Law and a pioneer in the sociology of law as well. In Marx’s unfinished excerpt work, he laid out Jhering’s legal-theoretical turn to the historical and sociological consideration of law, away from conceptual jurisprudence.

Marx’s extracts concentrated on Lange’s Altertümer and Friedländer’s Sittengeschichte. He focused on changes in family association, marriage and family law, to property law in a broader sense in which also the relations between individuals, families, and their clans or tribes played a role. Sketched in long passages, Marx summed up Lange’s account of the power of the Roman pater familias over the members of his family household: over his wife, his children and grandchildren, his free labourers, slaves, and bondsmen and -women, his livestock, house and land – consequently, over the central elements of the Roman domestic economy in the urban and rural context. The development of Roman property right was closely and directly connected to the size and composition of this urban and rural domestic economy, both reflect changes in the social structure of ancient society, both indicate underlying transformations in the ancient economy.Footnote 42

How Did Marx Study World History?

These excerpts and notes on the course of world history were created while Marx worked intermittently on the manuscripts of the last two books of Capital. In the summer of 1881, he broke off work on the last manuscript of the planned second book; in the summer of 1882, he interrupted work on his last manuscript of the planned third book, which also remained unfinished. Why was he doing extensive studies on world history at this time, instead of, as one might expect, focusing exclusively on the economic history of capitalism? Only by looking at the excerpts and notes in more detail can one understand the meaning of these digressions and excesses in the old Marx.Footnote 43

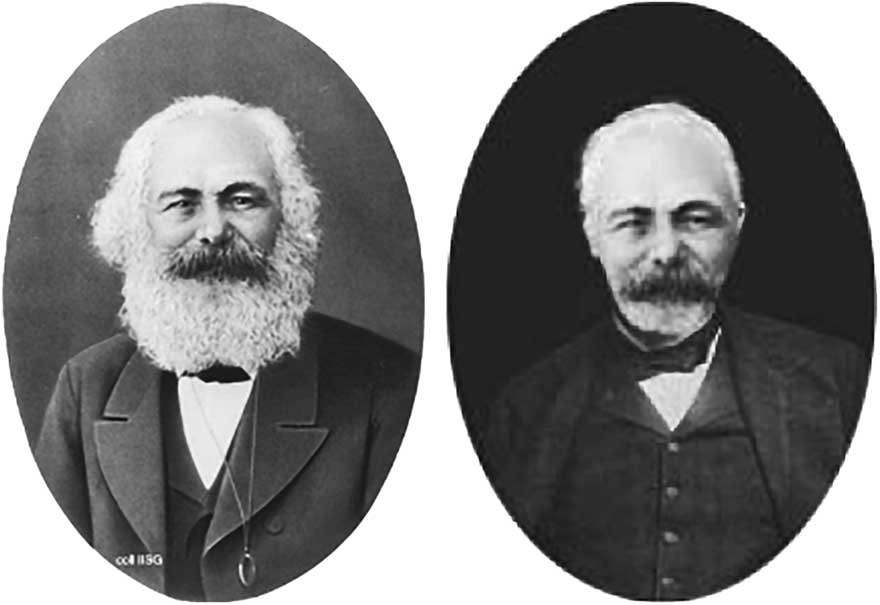

Figure 1 Left: last photograph of Karl Marx, taken by E. Dutertre in Algiers, on 28 April 1882. Right: a photomontage – based upon Marx’s own correspondence, where he said that the photo was taken just a short while before he went to the barber to have his hair cut and his beard shaved off, and shows how he may have looked after his visit to the barber. Left: IISH Collection BG A9/383. Right: creator and origins unknown.

Clearly, these notebooks are not about original research and also not simply about a collection of materials, because most of what Marx was reading he already knew, at least to some extent. He did not deal for the first time with the process of European and non-European history in 1881–1882 after all. This can be seen by his occasional corrections of factual errors, especially in Schlosser’s Weltgeschichte.Footnote 44 Therefore, it is a new attempt at self-understanding and self-clarification; it is about making preliminary work that could result in a new formulation, an extension and/or differentiation of the “guideline” that Marx had published in 1859 in the preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.

Marx generally followed Botta’s and Schlosser’s account in the excerpts, but certainly not every particular detail. Occasionally, Marx corrected his authorities, rectifying facts or referring to issues that Botta and Schlosser ignored or overlooked, falsely classified or assigned. Chronologically ordered – at times prospectively and retrospectively surveying history – Marx recorded events, important actors and their actions, but not simply for their own sake. People, families, clans, and dynasties are important, as without individual and collective actors there is no historical action or movement. Marx never shies away from giving the “great personalities” their own space, as some particular individuals are more important than others – even if he does so to contradict the legends built around them. In the books of Botta and Schlosser that Marx excerpted, he discovers the synopsis and summary, the order and assessment of materials that are, in large parts, already known to him, and, to a degree, the peculiar way of interpretation of these materials. Sparse comments, a few words and lines here and there, some short paragraphs allow us better to understand the excerpts in the context of Marx’s research process. Marx remained Marx. He did not study for fun, but pursued determined research interests.

The scope of Marx’s study of history, contained in the excerpts of 1881/1882, is striking: developing as far as possible from prehistory and early history to Greek and Roman antiquity, to late antiquity, the European Middle Ages, and up and into modernity (the second half of the nineteenth century). Marx gave no room to Euro-centrism; he considered world history in no way synonymous with “European history”, even if his two main sources, Botta and Schlosser, suggested otherwise. He studied the history of Asia Minor, of the Near East and Middle East, the Islamic world, the Americas, and Asia (with three centres of focus: India, China, and Central Asia). He also studied the history of North Africa. He extensively preoccupied himself with all areas of Europe, from the North (Scandinavia), to the West (France, England, Germany), to the South (Portugal, Spain, Italy and the Balkans) to the East (Eastern Europe, including Russia). He studied the colonial history of the most important colonial powers, and indeed also the history of the countries colonized by the Europeans (North America, Latin America, Indonesia, North Africa).

Conspicuous is the connection of political – i.e. state guided and state oriented –, frequently legal, and even more often military actions with technological and economic developments. Nothing less is to be expected from an author of a “materialistic” or realistic conception of history. Marx always falls back on what his sources of information provide on the economic “base” – and above all on the way in which political powers influence this “base”, intentionally or unintentionally altering and shaping it. He repeatedly notes down details on tax legislation, financial administration, and the organization of the apparatus of the state, as well as the territorial organization of public administration, the organization of the church, the structure of military organization or its reform. The sparse comments that Marx makes in the text refer to the historical role of individual persons, such as Martin Luther or Thomas Müntzer, who were shaped into legends. Marx read Schlosser, as it were, against the grain, against his main focus on the big issues and the main pomp and circumstances of state actions, and against his moralizing evil gaze on the ever-present actual “evil” power. Marx was fully aware that Schlosser employed a quite peculiar type of “enlightenment history”, one that was “philosophically” intended with highly subjective moral judgements on persons, actions, and events. This shaped Schlosser’s conception of history. Consequently, Schlosser’s treatment of the sources was naïve. He lost himself in his moral judgements and trusted the “natural and necessary course of things”. Hence, he saw “progress” everywhere he looked. Marx knew that he could not trust Schlosser’s account, as much as the latter emphasized the “basic knowledge of the particulars”.Footnote 45

What the Four Excerpt Notebooks Have to Offer

In the excerpts of the first notebook,Footnote 46 Marx commences with Botta’s account of the history of Rome from the year 97 BCE. He thus directly takes up his previous study of Roman history from 1879/1880 and continues it here, but with a different focus: the political economy and the organization of the Roman state during the imperial period and later in Rome’s development in late antiquity. Marx emphasizes the integration of the Roman Empire, especially in its core region around the Mediterranean in the trade at that time; he describes the trade of that period between Rome and India, and the trade routes that traversed Egypt and Syria (with Palmyra as a hub). From Botta’s account, Marx notes the details of the political – that is the administrative, bureaucratic, and also always military – reorganizations that occurred in late antiquity. He highlights the separation of the empire into a western and eastern Roman state, the different and also largely similar development of the parts – for example, the progressive separation of civil and military authority (which did not exist in the Rome of the imperial period), as well as the increasing independence of church organization as a third branch of the state apparatus. Marx traces in detail the construction of the civilian administrative organization and alongside it the organization of the military, in order to grasp the essence of these states.

Of particular interest for Marx are the details of the system of taxation and the numerous tax reforms of late antiquity. He knew the “financial nerves of the state” all too well, as Jean Bodin called them in his Six livres de la république.Footnote 47 Strong government and heavy and effective taxation are only possible if the administration knows where the potential taxpayers and their taxable wealth are to be found. In the Rome of late antiquity, a comprehensive taxation register is created for the first time in order to be able to recalculate land tax annually. For this purpose, an exact registry is required in which every plot of land and its property owner or proprietor are listed as well as a public valuation of all estates on the basis of their annual yields. The Roman administration already attempted to revise the tax register in a fifteen-year cycle (that is, the land register of plots and their assessment was adaptable to the intermittent period of change).

The downfall of Rome was and is the prime example of a great historical regression – the ruin of a great civilization. In his notes, Marx pursued the history of the destruction of the Roman Empire in the West under the pressure of the successive periods of migration of the different Germanic tribes, which dissolved the empire into a series of rivalling kingdoms. The development of Byzantium, the Roman Empire in the east, which had been trying to recapture the west-Roman territories or to resist the pressure of the barbarians, was very different. In Italy, thanks to the decline of western Roman state power, the pope attains political power and authority by dividing the country. Italy is separated into the Kingdom of Lombardy and the areas controlled by Byzantium, with both powers “cheating by turns”, as Marx remarks. Additionally, Italy’s primary protecting power, the Byzantine Empire, is weakened the more the pope seeks protection from foreign (i.e. non-Italian) powers. Marx adds that “this then becomes their traditional method, see Machiavelli”.Footnote 48 Increasingly, the popes began to behave as secular princes, and thus came into conflict with other secular princes.

Marx then followed the rise of France. In his extracts, the period of Charlemagne takes up a significant amount of space. What interested him is less the person of Charlemagne and his actions than the hunting down of the elements of the feudal system that arose in this period. This firstly occurs with the Lombard’s in Italy, where the “haut système féodal” is founded with the division of land under the dukes as minor kings. Charlemagne expanded this system by introducing it at all levels of administrative and military organization. He invented a stricter and smaller-scaled division of land, inventing new ranks, orders, and functions, counts, margraves, etc. and distributed the land among these new subordinate functionaries. Initially, it is only about military administration, the civil administration and system of justice remain unchanged. But, as a result of the permanent state of war feudal warlords take over the civil authority – against the freemen and the commoners, against the elements of local autonomy and self-government. Through the new feudal lords, Charlemagne promotes the repression of the “municipal councils”: “slavery and servitude side by side”, Marx comments.

Constantly looking forwards and backwards, exploring the chronology of Botta’s account, and studying different countries and regions by following their interrelated developments, Marx sketches the development in the Europe of the early Middle Ages. As he notes with the example of Sicily, different successive rulers influence the economy and social structure of the island. He describes in detail the reign of the Arabs who expelled the previously ruling Byzantines, restructuring the entire administrative organization and legal system. The order of property and inheritance introduced by the Arabs on the island was, according to Marx’s judgement, so good that the Normans, who followed them as conquerors, had nothing to alter. Marx describes the system of taxation that the Arabs introduced in Sicily and the development of agriculture and trade. The Arabs promoted the cultivation of olives as the main crop (already in pre-Roman times, olives were an important merchandise for the burgeoning trade in the Mediterranean; in Roman times, Sicily was the granary of the empire). Moreover, the Arabs abolished slave labour in agriculture (not slavery as such), replacing slaves with free labourers.

The history of Byzantium, which, in Botta’s account, only plays the role of an external power, leads Marx to deal with the history of Eastern Europe shaped by the Byzantine influence. He describes trade between the Byzantine Empire and Russian Kiev, in this way entering into the history of Russia (the northern Varangians). The Christianization of Eastern Europe, the Christianization of Russia, and thus the continuing (and lasting) influence of the eastern Roman, Greek Orthodox Church in large parts of Eastern Europe follows from the protracted wars of the Bulgarians, Russians, Hungarians, etc. against Byzantium.

The disintegration of the Frankish Empire after the death of Charlemagne makes the comparison of the historical development of the feudal system in Germany and in France possible, which transform in different ways and directions. Always looking to Italy, which plays such a central role in the history of the German empire, Marx summed up that, in France, the process by which the great feudal lords gained increasing independence from and autonomy against the monarchy easily went further than in Germany. But also in Germany, after the death of the last of the Carolingians, a destruction of monarchical authority occurs. As some of the great dukes transformed their duchies into hereditary family possessions, many small counties became independent. Nevertheless, the central power attempted to keep the feudal lords under the supervision of royal plenipotentiaries. The incursions of the Hungarians helped to implement a new push for royal authority: without heavy and readily deployable cavalry, without fixed large expenses and fortified cities, marauding cavaliers from the east could not be stopped.

Looking to Italy (and Germany), Marx notes the growing independence and transformation of the archbishops and bishops into great feudal lords – “small kings” who are only formally dependent on the German emperors and the Italian kings. Bishops govern in cities, in the Italian cities, beginning the struggle against the feudal system of domination in a land in which all local, regional, and territorial powers separately strive for independence. Increasing regionalism, the proliferation of small and ever smaller states, the weakening and the possible dissolution of the feudal bonds of vassalage predominate everywhere, benefitting from and promoted by the constant struggle of the great feudal lords and foreign powers with whom changing alliances can be concluded.

Marx is fascinated by the rise of the Italian merchant cities, such as Venice, Amalfi, Genoa, or Pisa, due to their increasing wealth and ever-expanding trade, their increasing involvement in world trade networks. Although nominally dependent on the margraves of the German Empire (in Tuscany, in Liguria) and the kings of Italy, this does not prevent them “from making powerful expeditions, to Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and also to far off lands in their own name”. They acted like small sovereigns, “concluding war and peace (and trade) treaties on their own account”. They were “self-governing municipalities, seats of Italian freedom”, as Marx writes. These city republics gradually gain their independence: “Venice from the outset as a grand municipe indépendant, Amalfi, but especially Pisa and Genoa little by little dissolve their feudal bonds; they were called republics”, which “in fact they were”. The example of these port and sea trading cities, “of these petites républiques reacted to the cities in the interior” of Italy.Footnote 49 Marx clearly sees the importance of those politically sovereign islands of early merchant capitalism in the sea of a still feudal agrarian economy. Such cities create permanent maritime trade expeditions and geographically wide-ranging trade networks. The city republics of Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, and Pisa – becoming wealthy thanks to their position and peculiar economy as centres and hubs of merchant trade and maritime traffic – could buy their independence; they were followed by the inland cities of Lombardy, Umbria, and Tuscany. The latter advance long-distance trade on land by developing highly specialized commodity production for world trade, as well as the first forms of commercial credit and money (commercial bills of exchange) (more or less at the same time with the maritime republics). Only in the margins of this excerpt does Marx touch on the bitter struggles of the rising capitalist republics against each other, and their changing alliances sometimes in conflict against and sometimes allied with their local princes, sometimes with the princes against imperial or papal dominion, and sometimes with the emperor or pope against the princes. In these struggles, they transform into early-modern territorial states, more often than not trying to gain control of important traffic routes and natural resources. Nor is Marx concerned with the role of the temporary, at times even lasting, alliances between these city republics that, bound up with each other in alliances and longer-lasting “city leagues” (like the later Hanseatic leagues in the North of Europe), take up the struggle against the great feudal powers of the time and even dared to defy the German Emperor.Footnote 50

As the city republics swiftly rise to bankers and financiers, they are the ones who embody early modern capital against the princes and the entire feudal hierarchy. But here, Marx follows the historical chronology, and turns (with Botta) towards the development of feudalism. He looks at the struggles of the feudal (ecclesiastical and secular) powers for supremacy in Italy in which the cities play a role as allies, but only as allies of the bishops, kings, and dukes and not as independent powers that counter the feudal order as a whole. Political power remains divided in a formal hierarchical system that has not yet found its concrete form. This is why Marx mentions and stresses the gradual transition to a written and legally stated feudal order beginning with the decree in 1037 of Konrad von Roncailles – “the oldest known feudal law (on feudal succession)”. This decree, which initially only regulated the succession of subordinate feudal tenures and assured the vassals of the greater worldly and spiritual lords the hereditary possession of their tenures, was developed in the following periods on the “foundation of written feudal law”. At the same time, it proclaimed, as Marx added with reference to Schlosser, the peace of God in order to put an end to the eternal feud. Under threat of the harshest ecclesiastical penalty, the “Treuga Dei” emerged – “armistice from Wednesday evening until Monday morning”: a step towards civilizing medieval feudal society.Footnote 51

Marx is not interested in the succession of rulers, the vicissitudes of wars and battles. He concentrated on the change in political form, noting great innovations. The Normans are the first who, in the context of feudal rule in Sicily and in the Kingdom of Naples, establish a parliament, which is also introduced in Normandy. It is a parliament of nobles with two houses or two assemblies sitting twice a year to deliberate [Beratung] on general affairs, split into a “bras (chambre) baronial” and a “bras ecclésiastique”. Later – once the cities that have become rich could buy themselves from the dominion of the barons and become free – a third house is created, the “bras (chambre) of the deputies of the freely purchased cities, called bras domanial”.Footnote 52 In Sicily, they are preserved and are often convened, Marx notes.

This first excerpt notebook ends with the history of the crusades, which Marx pursues in great detail. Before he comes to this, however, he deals extensively with the development of the political dominions that arose in the wake of the Islamic conquest of the Near East, Middle East, North Africa, and Asia Minor – reaching as far as Persia and India. In this, Marx goes beyond Botta, but without mentioning his sources. Marx describes the Caliphates of Baghdad, Mosul, etc., which arise as a specific form of empire in constant struggles against Byzantium. The caliphates were organized by their rulers into many feudal principalities, dissolving the new empire into “many little states”. Thus arose the structure of the local and rivalling small kingdoms – subordinate to no overlord – which the leaders of the European crusades encountered in Asia Minor and the Middle East. Marx records the main events of the first crusade with the founding of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, thus with the first European feudal states in the Near East.Footnote 53 In order to comprehend the role of the various European feudal powers cooperating in the crusades, Marx begins by surveying the political development of the feudal states in England and France – only to quickly return to the crusades themselves. By means of the crusades, the Italian city republics become rich and powerful as they control the logistics of these major military expeditions. For Marx, this is a reason, breaking with the chronology, to insert a comprehensive account of Venice, and its political and economic development from the fifteenth century until the time of the crusades.

The crusades end with a defeat, but are continued within Europe itself (in the south of France, in Ireland, and in Spain). The war of the small Islamic kingdoms, temporarily united through the crusades, continues against Byzantium and then against the Christian empires in the south east of Europe. The eastern European feudal states lead a broader crusade against the incursion of the Mongols in the thirteenth century. This is a reason for Marx to make detailed notes on the origin and development of the Mongolian Empire. Here, Marx takes leave of Europe in order to deal with Central Asia, Persia, India, and China under the rule of the Mongols.

At the beginning of the following second notebook,Footnote 54 Marx returns to Europe to the period of the last crusades (in the thirteenth century) – to Germany, France, and Italy. He goes into particular detail on the reign of the last emperor of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, Frederick II, who resided mainly in Italy. The most extensive amount of space is taken up by Marx’s records on economic development in the Italian city republics at the end of the thirteenth century. It is completely clear that Marx saw the beginnings of modern capitalism here: the first systematic development of arable farming, the emergence of a science of agriculture, the beginnings of maritime law (in which the Catalans and Italians are involved), and the origin and the beginnings of the modern banking industry in Italy. No wonder it was the Italians who “raised the many levies and taxes of Christianity everywhere in Rome and after having superior numbers there”, it was the Italian merchant cities that themselves “preferred to levy by means of bill of exchange business”. Marx lists an entire series of cities (Rome, Genoa, Venice, Piacenza, Lucca, Bologna, Pistoia, Asti, Alba, Florence, Siena, Milan) that commonly operated a “joint main bank” in Montpellier, which made credit deals with the French king and other nobles. In his notes, Marx records the development of the Italian merchant republics between which a certain division of labour took place. Financial transactions were driven essentially by the cities inland, while the port cities, such as Genoa and Venice, had the “actual international trade”Footnote 55 under their control with trade settlements throughout the Mediterranean, on the Black Sea, and on the Red Sea. From Crimea, they operated long-distance trade with China. In a very detailed fashion, Marx records the political development of the individual city republics, in particular the inner development of Florence that ends with the complete removal of the aristocracy – this development captivates him. Next to Botta, Marx uses Machiavelli as his main source in order to describe the course of the internal power struggles in Florence. Similar conflicts rage in Pisa, Pistoia, Milan, Venice, and Vicenza in which the nobility always interferes.

In the second notebook, much space is devoted to the development of Germany in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Marx notes the main events and main figures, including the special development of Austria from the thirteenth until the fourteenth century – always reflecting on the particular development of France during the same period, that is, from 1300 to 1470. As in the first notebook, Marx combined details on political and legal development, on wars and campaigns, and on administrative organization with information on economic and technological development. Likewise, he attempted to determine the great consequences of events: following historical development in connection to Germany and Italy, France and England, Spain and Portugal. Even when he traces in chronological sequence the main stages of the Reconquista and the ruin of the Kingdom of the Moors on the Iberian Peninsula from beginning to end, he is concerned about the long-term consequences. The independence of Portugal is an important event because the country emerges as a naval and merchant power externally oriented towards Africa, and is a pioneer of European expansion.

Marx pursues further, just as he had in the first notebook, the development of the feudal structures in Germany and Italy – and in particular the development of the Italian cities now united into leagues that alternately fight against the German emperor and against each other. He collects and orders the facts that Schlosser provided him: on the development of feudal domination in Byzantium, in the rising Ottoman Empire, and in the caliphates of the Near East and North Africa. The history of the Mongolian Empire founded by Genghis Khan, its enormous expansion through war and conquest, its temporary stabilization, and its ruin invites Marx to reflect on the limits of political power over vast territories. The Mongolian Empire reveals the limits of a purely land-based power that lacks mastery of the sea. This is precisely the type of political-military power that the small state structures on the fringes of Western Europe directly build – Portugal, Holland, England – on the foundation of naval domination, harnessing newly constructed empires. The development and expansion of the Ottoman Empire, the demise of Byzantium with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, shifts the great world trade routes – away from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, a shift that is felt first by the Italian maritime republics Genoa and Venice.Footnote 56

A state of almost constant war reigns in this period in England and in France: war of the great noble houses against each other – the Hundred Years’ War over the possessions of the English kings in France, the War of the Roses between rivalling noble factions in England – as well as civil wars of the crown in alliance with the cities against the princes and the princes in alliance with the cities against the kings. In this permanent war, entire counties, duchies, and kingdoms rise and fade away. Marx himself notes the rise and subsequent demise of Burgundy as an independent state between France and Germany. The lesson is clear: states and kingdoms have no natural territories or borders, and no peoples that belong to them, they can be destroyed; feudal states fight for land and people, territorial possessions, for cities, and their riches. There are struggles between rival political powers: kings, princes, ecclesiastical princes, and cities – fought out by means of changing alliances between all parties concerned.

The extracts in the third notebookFootnote 57 concern the period from approximately 1470 until 1580. Marx begins with the protracted conflict of the ascending great European powers and rivals France and Spain, the conflict for predominance in Italy, which is divided between the Church, the city republics, and the small principalities, and after the withdrawal of the German emperor has no overlord. The war of conquest against the Italian city republics that the French and the Spanish kings carry out in competition with each other, the one advancing from the north, the other from the south, against the alliances of the popes, cities, and occasionally the German emperor, alters the political landscape and the character of the city republics. The city republics defend their independence from the great powers, their urban freedoms, and thereby use the rivalries of the great powers, in changing alliances. In his notes, Marx paints a picture of the situation in Florence in the period of Savonarola. He compiles extensive details on the life story of Savonarola, from his beginnings as a wandering preacher of repentance, to his rise as the actual ruler of Florence after the expulsion of the Medici in 1494, to his defeat and execution in 1498.

Savonarola is only a harbinger of the movement of reformation that seizes Germany and France in the sixteenth century. Marx saw this clearly as a political, social, intellectual, and moral revolution that, together with the Counter Reformation – the counterrevolution – it produces, leads to a shift to a political order in which the rising middle classes, the new bourgeoisie in particular, attempt to assert themselves against the kings and princes by means of the new economic power of capital, of urban commercial and financial capital. As Marx commented,

[T]his struggle of monarchy against overpowering capital, personified by Venice, occurs directly in the period when quite other essential [forces] are at work (America, etc., discoveries of gold and silver, colonies in the interior, financial difficulties for the standing army) in order to bring feudally tainted monarchy from its origin in the feudal state under the control of the capitalist economy, and hence of the bourgeoisie, which then also takes place in the struggle between the papacy and the Reformation.Footnote 58

Not only kings, but feudal lords of every rank also feel the new power of capital and adapt themselves to it. Frequently, Marx noted the details about the practices of the organized robber barons – that is, of the lower nobility and its protagonists (such as Franz von Sickingen who Lassalle elevated to a tragic stage hero) – in terms of buying up the debt claims in the cities from the merchants and then, in their own way, i.e. through robbing and plundering, to exact their debts.

Within the course of events in the German Reformation, the development of Protestantism – with various peace agreements until the middle of the sixteenth century and the German Peasants’ War of 1524/1525 as a climax – differed in comparison to neighbouring countries, where it led to civil wars carried out as religious wars, as in France and the Netherlands. Marx was well acquainted with the German Peasants’ War, probably by means of Engel’s account and it is briefly recorded in a few main events. Since the connection between Thomas Müntzer and the Thüringen proto-proletarian is important for Marx, he is emphasized as a protagonist.

The contemporary chronicler Sebastian Franck, who endeavours to have an unpartisan view on the events, is also the first writer of a world history and universal history in the German (not Latin) language. According to Marx, he is worthy of an extensive commentary. Martin Luther, by contrast, comes off badly. Marx reprimands the hero of the Reformation, “this monk impedes everything progressive in the Reformation”,Footnote 59 and, in this sense, he comments on a number of Luther’s writings and actions. Schlosser saw things entirely differently. In a long section, Marx attempted to summarize the consequences of the Reformation – especially in view of the fragile political reorganization of the German Empire.

In the end, Marx looks once more to England and traces the development of the English monarchy of Edward VI until Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I. In a schema, he portrays the complicated family relationships in the English dynasty. He also sees clearly that the early modern states alternate family property and family businesses amongst each other or are noble families related to each other. Naturally, Marx, who celebrated Shakespeare his entire life and in whose house a real Shakespeare cult prevailed, was strongly interested in the Elizabethan age.

In the fourth and last notebook,Footnote 60 Marx resumes his recording of the course of the European religious wars: the second period of the French Wars of Religion until the peace agreement of the “good king” Henry IV; the beginning of the Dutch struggle for freedom against Spanish dominion; the war between Spain and England until the demise of the Armada; the development of Scandinavia, Eastern Europe, and south-eastern Europe; the Turkish wars in the Balkans and in Hungary, which kills off the Reformation in Austria and in all of southern Europe.

This panoramic view of the development of Europe in various parts is immediately followed by a detailed account of the course and the events of the great European war, the Thirty Years’ War, which was fought out in Germany. The Dutch Republic, neither an aristocratic, nor people’s republic, but the first bourgeois republic, which is governed by the “Heren” (the “Heren”, as they are also officially called in the Dutch language, are urban merchant and financial capitalists) firstly attain their independence at the end of this war. The Dutch Republic is the most developed capitalist country in the seventeenth century. Marx records some of the innovations that explain the economic success of the republic. By contrast, Marx notes the German conditions shortly before the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618: the enormous political, social, and economic fragmentation in and between the territories of the empire. In a long review of the history of Scandinavia and Russia, Marx catches up on what he had left out: Russian history since 862 is shown in four long periods, until the beginning of the seventeenth century.

What then follows is the detailed account of the course of the war from 1618. For Marx, it is about major international politics, the role of the northern Protestant great power Sweden, and the role of the French Catholic great power. Marx goes into detail on the inner development of France from 1598 until 1639 under various governments and prime ministers until Cardinal Richelieu. The major and minor military and administrative reforms interest him, through which, in France (and only there), a centralized unitary state is constructed. The foundations for European great power politics, which the governing cardinals Mazarin and Richelieu deliberately conduct, are also in the interests of the Catholic Church that they establish as a state church. In Germany, what is at stake is the elimination of or adjustment to the consequences of the Reformation, with the expropriation of church goods. “As everywhere in the Thirty Years’ War: war is about the property of the Church!”Footnote 61

These Schlosser excerpts conclude with the events that led to the 1648 Peace of Westphalia: that European blueprint for peace that ushers in the modern period of international politics. Marx gives a detailed overview on the course of the negotiations, which already began in 1639, representing the different peace proposals and political plans including documents. The last stages until the conclusive peace agreement, the period from 1646 until 1648, during which the delegations of all of the involved parties negotiated in Osnabrück and Münster, Marx portrays, month by month, followed by a chronology of the negotiations. The detailed reproduction of individual clauses of both of the comprehensive peace treaties then follows: the one concluded in Osnabrück between Sweden, the emperor, and the Protestant imperial estates and the separate one concluded in Münster between France and the remaining warring powers. Finally, on 29 October 1648, the general peace agreement between all parties concerned takes place at the town hall in Münster.

Marx, the trained jurist, deals with the agreement in three sections. Firstly, on Sweden and its allies and the relevant clauses (cessation of territories, compensations, etc.); secondly, on the faith [Religion] related clauses. There, he emphasizes the central provision “cuius regio, eius religio”. No government needs to tolerate citizens who do not belong to their religion; they must be given three years to emigrate. And, thirdly, concerning clauses on the constitution of the German Empire. The most important clause: the German princes, who had been denied the right to conclude alliances among themselves and with foreign powers, were, from that moment onwards, granted the right to do exactly that without any consideration of the emperor or the empire. Yet, the latter’s interests and prerogatives were only granted formally “with the easy to circumvent clause that such an alliance contained nothing against the emperor and the empire”. Thus, the “sovereignty” of the German princes was confirmed, who see themselves promoted to masters of small independent states.Footnote 62

On the final pages, Marx returns once more to the history of England – the period from the death of Elizabeth until the coronation of Charles I. He concludes with an abbreviated account of the prehistory of the English Revolution of the seventeenth century, after the Dutch war of liberation, the second “bourgeois” revolution of modernity.

This last notebook directly shows, once again, the strength of Marx as a historically well-informed social scientist, who easily alternates from the inner development of specific countries to major European and international politics without, however, losing sight of the economic foundations of the whole. From the outcome of the Thirty Years’ War, and even afterwards, there is no clear hegemony of one or the other of the great powers in Europe. But Marx had the future main players firmly in view, the rising continental great power France and its subsequent rival England. Cardinal Richelieu, the inventor of the political concept of “Europe”, a Catholic Europe under French hegemony, holds his attention. Richelieu had a plan that he skilfully and consistently pursued; he is the actual victor of the “Peace of Westphalia”, who broke the German Empire as a political actor for more than a hundred years.Footnote 63 Marx definitely views the “Westphalian system” in a critical fashion – and he in no way comes up with the idea, which is still popular today in the academic discipline of international politics, of considering it as the beginning of a system of national states.

World History – What Does It Mean?

For Marx, the concept of world history is not only a historiographical, but also a historical category. The rise of modern capitalism, its spread throughout Europe and the adjacent regions of the world made an “epoch” in world history. And it did so in the emphatic sense of the thesis that Marx and Engels initially establish in the outlines of the critique of the German Ideology and then in the Communist Manifesto: only with modern capitalism can there really be a world history. This is because only modern capitalism creates the material basis for a world society with the world market, world trade, and world finance, and the new international division of labour that gradually encompasses all countries, regions, and continents. World economy and world politics are clearly combined in Marx and Engel’s political theory. Capitalism is considered as an inherently expansive, principally boundless economic system, hence as a world system. Its political forms, starting at a local and regional scale and scope, expand towards the larger territorial states with unified legal systems and material infrastructures, and eventually go beyond the framework of national states and state systems based upon the nation as all “capitalist” states are transformed into hybrids of national states and (multinational, colonial) empires.Footnote 64 The first modern world economic crisis, the crisis of 1857/1858, encouraged both Marx and Engels in the conviction that the world market, the world economy dominated by capitalism, had already become a reality. The capitalist mode of production was permeating the whole world, thus fulfilling its historical calling. But the development of the world market and a capitalist world economy proceeds very unevenly. In one part of the world, modern capitalism can be studied in its maturity, whereas in another part of the world it is still just emergent or on the rise: “We cannot deny it”, Marx wrote to Engels in October 1858,

that bourgeois society has for the second time experienced its sixteenth century, a sixteenth century which I hope, will sound its death knell, just as the first ushered it into the world. The proper task of bourgeois society is the creation of the world market, at least in outline, and of the production based on that market. Since the world is round, the colonization of California and Australia and the opening up of China and Japan would seem to have completed this process.

However, the following “difficult question” arises: if the capitalist mode of production and bourgeois society in Europe are ripe enough to overcome them, will a socialist revolution “in this little corner of the earth” not “necessarily be crushed […] since the movement of bourgeois society is still in the ascendant over a far greater area”?Footnote 65

In the manuscripts that we know as the German Ideology, the discourse on world history receives, in connection with Hegel and directed against the left-Hegelians, a new form – a downright “materialist” one:

The further the separate spheres, which act on one another, extend in the course of this development and the more the original isolation of the separate nationalities is destroyed by the advanced mode of production, by intercourse and by the natural division of labour between various nations arising as a result, the more history becomes world history. Thus, for instance, if in England a machine is invented which deprives countless workers of bread in India and China, and overturns the whole form of existence of these empires, this invention becomes a world-historical fact.Footnote 66

World trade was the avant-garde, large-scale industry that was the lever of this revolution, propelled by universal or worldwide competition, which “produced world history for the first time insofar as it made all civilized nations and every individual member of them dependent for the satisfaction of their wants on the whole world, thus destroying the former natural exclusiveness of separate nations”. The world market as a “primary natural form of the world-historical cooperation of individuals” subjects them all to a form of “all-round dependence”,Footnote 67 which appears as an alien power and therefore remains just as incomprehensible as world history.

Precisely this thesis is repeated in the Manifesto of 1848: modern capitalism, along with large-scale industry, which produces for the world market, sends its agents “over the entire globe”; it creates a new “mode of production and commerce” of global reach overcoming former national and local isolations; it destroys the former forms of national and regional “self-sufficiency” by global competition and “universal inter-dependence of nations”, and forces all countries under the spell of the world market, whose economic cycles determine their every movement.Footnote 68

Once more, Marx emphasizes this conception in an incidental remark at the end of his rapidly jotted down Introduction of August 1857, as a side note to be worked out later: “(Influence of the means of communication. World history did not exist always: history as world history is a result).”Footnote 69 The reference to the means of communication here is not incidental. The first submarine cable had been laid in 1851. In 1857, the year of the crisis, the first attempt was made to lay a transatlantic cable for telegraph communications between London and New York. That succeeded one year later.

Initially, the mode of capitalist production in its fully developed form – that is, of industrial capitalism – creates a world market and a world economy; permits and requires world history: that is, political action on a world scale. The research manuscripts from 1857/1858 contain only a few powerfully sketched theses to this end: “The tendency to create the world market is inherent directly in the concept of capital itself”; initially, capital pursues the tendency to expand the market over and across all borders, to create new markets, and “to propagate” everywhere its own mode of production. Only capital “creates bourgeois society and the universal appropriation of nature and of the social nexus itself by the members of society”.

Hence the great civilizing influence of capital;Footnote 70 hence its production of a stage of society compared to which all previous stages seem merely local developments of humanity and idolatry of nature. […] It is this same tendency which makes capital drive beyond national boundaries and prejudices […], as well as beyond the traditional satisfaction of existing needs and the reproduction of old ways of life confined within long- established and complacently accepted limits. Capital is destructive towards, and constantly revolutionizes, all this, tearing down all barriers which impede the development of the productive forces, the extension of the range of needs, the differentiation of production, and the exploitation and exchange of all natural and spiritual forces.Footnote 71

Revision of the Guideline – States and Markets: The Emergence and Rise of Modern Capitalism in Europe

From the beginning, since 1844, Marx pursued another project, the critique of politics that was originally connected directly with the critique of national economy (then political economy) only to be deferred in favour of the second critique (but never abandoned). In various later writings, Marx repeatedly attempted to briefly sketch the development of the states in Europe: in The Class Struggle in France of 1850, in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte of 1852, in his series of articles on the English constitution and English politics of 1853/1854, in his series of articles on Revolutionary Spain of 1855, and on The History of Diplomacy in the Eighteenth Century of 1856/1857, as well as in Herr Vogt of 1860 or The Civil War in France of 1871.

In these sketches, a clear sequence of stages and direction is given to European development, which goes from the unstable co-existence of different proto-states or political powers tending to transform into states and dispute the same territories and spheres of influence with one another (feudal states – a term that Marx often uses – with a more or less distinct “feudal” hierarchy, city republics and associations or leagues of cities, the Catholic Church), to the formation of territorial states under one centralized or centralizing supreme power, to absolute monarchy, and finally to constitutional monarchy and the modern form of a (bourgeois) republic. Consequently, Marx sketches the development of the nation state from continually failed attempts within the European empires (following the Roman Empire to the establishment of the European states system), from the defence from invasions from empires external to Europe to the establishment of a European political system. According to Marx’s conception, France is the classical land of state development. For, in France, he sees both a long-lasting tendency towards the construction and expansion of a centralized, specialized, bureaucratically organized state power run by professionals as well as a sequence of changes (occasionally considered by Marx in the manner of Polybius as running through a cycle) of the state and forms of government combined. The necessary historical endpoint of this modern development is a unified, well-organized, centrally controlled territorial and national state in the form of a bourgeois republic, with a parliamentary government and universal suffrage. Marx had described the “classical” case of French state development many times.Footnote 72

Already in the 1850s, Marx sees clearly that many countries and regions in Europe do not precisely fit this schema. Spain, for example, does not. In the first of the series of articles on Revolutionary Spain, Marx compares in 1855 state development in Spain with the rest of Europe. In Spain, absolute monarchy arose first, but without centralization, without “social unity” being imposed from above, and with the political rights and freedoms of the cities and estates that had fallen victim to state development in other European countries.Footnote 73 Another special case, the state development of Russia, Marx characterizes in his series of articles on The History of Diplomacy in the Eighteenth Century from 1856/1857. He explains the particular formation of the Russian state historically, from the protracted struggle against the dominion of the Mongolian Empire, as a purely tributary proto-state. The unification of Russia under the dominion of Moscow – in the struggle against the domination of the Mongols and against the Russian city republics – explains the particular form of modern state formation that Russia begins under the reign of Peter the Great.Footnote 74 This contribution to political history by one of the great powers, was strictly based upon the historical sources, and the presentation commenced, as Marx stressed, not “with general considerations, but with facts”Footnote 75 and offered “new material for a new history”, instead of “new reflections on well-known materials”.Footnote 76 Thus, this would be an actual test of the new conception of history together with “historical discoveries” – Marx was rightly proud.Footnote 77

Thanks to his intensive examination of British politics, of the Irish question, and the colonial politics of the empire, it quickly becomes clear to him that English or British state development also do not fit into this schema, despite the early development of a national state on the island. Finally, there is Germany, which, for the most part, still had to undergo its modern state development. Then, the United States, with which Marx is repeatedly and intensely concerned: a bourgeois republic of European origin that went from one bourgeois revolution to the next and formed a democratic state, but without a state apparatus comparable to European countries.

In his historical-political studies, as in his historical-economic studies, Marx becomes increasingly conscious of the connections between the development of the modern state – even a European system of states – and the development of modern capitalism. State power is not only the “lever” that accelerated the emergence and development of modern capitalism, without developed statehood the capitalist mode of production cannot be imagined. Without the state there would be no market, no trade, no monetary, or credit system. Without the state there would be no factory system, no modern wage labour (and certainly no modern slavery).

Here is a lesser-known example from Marx’s economic manuscripts. In the fragment of the first outline from A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (the original text, today known as Urtext), Marx stressed the connection between the modern state and the development of the modern monetary system:

Absolute monarchy, itself already a product of the development of bourgeois wealth to a level that is incompatible with the former feudal conditions, requires the general equivalent as a material lever – in accordance with the uniform general power that must be capable of exerting itself at all points of the periphery –, of wealth in its ever-ready form absolutely independent of particular local, natural, individual relations. It needs wealth in the form of money. Therefore, absolute monarchy is working on the conversion of money into the universal means of exchange and payment. This can only be established through forced circulation, which makes products circulate under their value.Footnote 78

Here, Marx describes a historical form of the modern state, absolute monarchy, whose economic mode of existence, the dependency on taxes, and political action, requires the transformation of all taxes into money taxes as a lever for the development of a modern monetary system, which is only adequate for the capitalist mode of production. It is the “epoch of the emerging absolute monarchy” in which the art of finance consists of turning all products into commodities and all commodities into money and, indeed, “by force” with the full commitment of state power. With the full use of the power of the state, all taxes can be transformed into and levied as money taxes. It is this form of the state in its particular epoch that initially brings about one of the preconditions of capitalism – a functioning, general circulation of goods and money, a money that fulfils all of its necessary functions at all times and everywhere.Footnote 79

To adequately grasp this connection of state and capitalist development, Marx considered the most difficult point. In Capital, he will deliver the foundations, the “quintessence” of his critical theory: the “development of the sequel” could “easily be pursued by others on the basis thus provided” – yet with the one exception “of the relationship between the various forms of state and the various economic structures of society”.Footnote 80

The detailed studies on the early development of capitalism in the United States of America and in Russia, which he pursued from 1870, encouraged him in the view that there was not one historical capitalism, no single line of capitalist development, but many. The development of capitalism as an economic and political world system was a more complex history than he had initially anticipated. Both new capitalisms, the US-American and the Russian, developed themselves in connection with states, which, in many respects, did not correspond to the Western European model. American capitalism developed so fiercely that it began to overshadow the classical model of industrial capitalism, England.Footnote 81

Some dominant leading perspectives in Marx’s studies on world history from 1881/1882 appear in the arrangement of the material and in his emphasis. This is also true of the way in which he read Botta and Schlosser, and how he treats their accounts in his notes. At the centre stands the development of the modern state, but considered (in the sense of Marx and Engel’s conception of history) as a process related to the development of trade, agriculture, mining, fiscalism, and spatial infrastructure. Much attention is given to the connection between state and law and administrative organization, as well as the (good historical-materialistic) connection between the state and war or military organization and technology.