“Out, Out, Corruption! … We want Jordan to stay free!

No course and no alternative … for corruption, except to leave!

[…]

Phosphates … They sold it! They stole it! …

Potash … They sold it! They stole it! …

The Electricity [Company] … They sold it! They stole it! …

The Water … They sold it! They stole it! …

Aqaba … They sold it! They stole it!”

Protest chant, Amman, Jordan, 2011Footnote 1

“They stole the phosphate and did not privatize the company.” This is what Salem tells me, sitting at the far end of a conference table in his offices at the Jordanian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (JFITU). His statement punctuates a list of grievances – against the Jordanian Phosphate Mines Company (JPMC), its now-exiled CEO, and even the government – which motivated his labour activism.Footnote 2 Yet, as a JPMC employee himself, he surely knew that the company had been privatized in 2006, albeit under opaque circumstances. So, what exactly did he mean that the company had been “stolen” instead of privatized? In my discussions with both labour and non-labour activists in Jordan – and as reflected in the protest chant reproduced above – Salem's sentiment, that some privatizations were akin to theft, was a common refrain. Yet, Salem's framing suggests that it was not that privatizations were seen as bad per se, but that the practice of privatization could be perceived as either legitimate, or illegitimate. To untangle the ambivalence undergirding perceptions of privatization as well as other dimensions of “structural adjustment” in Jordan, this article posits that certain practices of state divestment violated widely “known and accepted rules and principals” in Jordan, which constituted a moral economy around the just (re-) distribution of the socio-economic benefits derived from national resources.Footnote 3 I argue that the disruption of this moral economy became a “framing discourse” for struggles, peaking in 2011 and 2013, against structural adjustment in Jordan by labour and non-labour social movements.Footnote 4

In doing so, I also attempt to sketch out a qualitative distinction between the “food riot” and movements against privatization, through juxtaposing the moral economy of commodities with what I conceptualize as a moral economy of national resources. In Jordan, mass unrest in response to austerity policies and rising prices in 1989 and 1996 exemplify the “modern” food riot, defined by Waldon and Seddon as “protest incidents […] triggered by visible and abrupt exactions which simultaneously generate palpable hardship, a clear perception of responsible agents, and a sense of injustice grounded in the moral economy of the poor”.Footnote 5 By contrast, as a modality of adjustment, the privatization of public assets stands as perhaps the most structural – systematically reconfiguring and dispossessing livelihoods and communities as much as companies.Footnote 6 Correspondingly, I want to suggest that, in the aftermath of King Abdullah II's accelerated programme of privatizations after 1999, social resistance in Jordan has become more systemically oriented and transgressive – belying the notion that the Arab uprisings “missed” Jordan.

In what follows, I trace the development of a moral economy around Jordan's national resources, specifically (but not limited to) phosphate and potash.Footnote 7 I draw primarily on data collected through interviews with activists as well as Jordanian newspaper accounts of protest events. Because my discussions were limited to those either directly or indirectly involved in activism during events that occurred nearly ten years prior to my fieldwork, my aim is not to reconstruct a “collective subject” (see Mélanie Henry's contribution) or to assert that the discourse described by my interlocutors was homogeneous, nor, indeed, to claim that it constituted a counter-hegemony. Rather, my goal here is to demonstrate that a diverse cross- section of social movement constituencies – spanning labour and non-labour movements (and fractions within and across those movements) – perceived privatizations as a moral violation, which, in turn, informed transgressive activist practices and discourses.

A MORAL ECONOMY OF NATIONAL RESOURCES

In E.P. Thompson's early and influential formulation, the grievances of working-class rioters in eighteenth-century England “operated within a popular consensus as to what were legitimate and what were illegitimate practices” in the sphere of inherently unequal market relations.Footnote 8 This focus on ground-up, popular conceptions of legitimate state, market, and social practices is central to the conception of moral economy developed in this article. We can see a slightly different perspective in James C. Scott's The Moral Economy of the Peasant, wherein moral economy expresses the shared social understandings governing the terms of just economic distribution grounded in an “implicit moral threshold” of basic subsistence.Footnote 9 While retaining an emphasis on shared perceptions of legitimacy and redistributive ethics between unequal classes, recent scholarship has eschewed readings of Thompson and Scott that limit the applicability of moral economy primarily to pre-capitalist or transitional contexts or actors.Footnote 10 As Palomera and Vetta assert, any prevailing socio-economic order – including capitalism and its neoliberal variant – necessarily reflects past struggles through which the institutional, material, and discursive elements of hegemony were set into motion and became embedded into daily experience.Footnote 11 Thus, moral economy in this sense serves as a way to capture the localized symbolic and material arenas in which prevailing social orders (as the product of past struggles) are legitimated, (re-) produced, and (re-) interpreted.Footnote 12

In some conceptions, the moral economy also demarcates the outer limits of social struggle. For example, in Walton and Seddon's global study of “IMF riots” (incited by austerity programmes), the horizon of struggle often ended at a demand for prices to return to their previous levels, rarely endangering the globalized circuits of structural adjustment and free market capitalism.Footnote 13 Posusney makes a similar claim with regards to “restorative” labour protests in Egypt under the developmentalist order of President Gamal Abdel Nasser.Footnote 14 In this framing, social mobilization arising from moral economies is seen as conservative – that is, principally concerned with “resurrecting the status-quo ante” – rather than as capable of producing a “new consciousness” or raising transgressive demands against the state.Footnote 15

By contrast, contemporary struggles against neoliberal orders, such as the “Pink Tide” in Latin America in the 2000s and, as I argue, struggles against privatization in Jordan, open up the possibility that innovative social movements, capable of articulating new and transgressive discourses, may emerge as moral economies break down.Footnote 16 Indeed, as Wood has argued, Thompson's overall intellectual project – including his work on moral economy – should be read as demonstrating how consent to rule is always partial and never entirely top-down: rather, unequal power relations are often incompletely tolerated and unevenly (re-) produced across space and time.Footnote 17 Moreover, in such moments of rupture, as Chalcraft has shown, social actors may come to question and challenge the hegemonic “common sense” that keeps subaltern consent in place.Footnote 18 In this article, I build on this conception of moral economy as reproducing hegemony while also providing openings for its dissolution. At the same time, I also move beyond a focus on specific commodities linked to subsistence (e.g., bread, rice, fuel),Footnote 19 to propose that national resources can underpin – both materially and symbolically – moral economies, while also forming the basis, however ambivalent, for transformative discourses of resistance.

To do this, I draw on Lyall's work on the “moral economy of oil” in Ecuador, which explains how state elites “cultivated expectations that oil resources ought to ensure for all citizens a minimum level of development (i.e. public works, employment and welfare programmes)”.Footnote 20 In the process, Lyall also sketches out a key distinction between subsistence-based food riots and revolts around national resources, which “manifest not only in local settings of protest, but also on a national […] scale”.Footnote 21 While Lyall's focus is on the top-down manipulation of redistributive ethics, we can also expand it to incorporate the bottom-up (historical and current) struggles that are always a part of moral economy. In this sense, the moral economy of national resources serves as a prism through which the working class and the urban and rural poor alike experience what Harvey has theorized as “accumulation by dispossession”, or the process through which the “corporatization and privatization of hitherto public assets […] constitute[s] a new wave of ‘enclosing the commons’”.Footnote 22 Hence, more than other aspects of structural adjustment, privatization – by commodifying national assets and, indeed, the public sector itself – precludes the possibility of a return to the status quo ante.

The argument: Moral economy and protest

To summarize, in certain cases, privatizations may be experienced as a breach of legitimate state–society practices, creating the possibility for innovative social movements and transgressive demands to emerge. In turn, I argue that through the moral economy of national resources, differently situated social movement constituencies across Jordan – workers, the urban and rural unemployed, denizens of “special economic zones”, university graduates, professionals, and many others – were mobilized to challenge the hegemonic “common sense” of the state's neoliberal project.Footnote 23 This occurred, in reciprocal fashion, across two levels. Firstly, negative experiences of privatization revealed to disparate actors the contradictions between the king's neoliberal promises – for example, that state-run enterprises had failed, and privatization was the only path to prosperity – and the deleterious material consequences wrought by many privatizations. Even actors not directly affected by privatizations came to associate them with their own poor material circumstances and the highly unequal distribution of economic prosperity in Jordan. Secondly, those localized experiences of privatization were focused, articulated, and transformed by different social movement constituencies so as to include and appeal to local and trans-local movement constituencies, mass audiences, and media commentators.Footnote 24

Denouncements of “bad” privatizations were articulated by demonstrators through accusations of pervasive corruption (fasad) and by vilifying those most closely associated with illegitimate privatizations as thieves (haramiyya). Taken together, those articulations worked to generate a mutually comprehensible discourse of resistance to the state's neoliberal project, as reflected in the images, poster slogans, and chants of demonstrators between 2011 and 2013, and as expressed to me in interviews with activists. It should be noted that this discourse had significant limitations. Specifically, while between 2011 and 2013 some protesters became increasingly daring in their calls for the “overthrow of the regime” (isqat al-nizam), popular consensus generally remained limited to demands for the “reform of the regime” (islah al-nizam).Footnote 25 Nevertheless, the fact that an anti-neoliberal discourse continues to pervade mass demonstrations and strikes (most recently in 2018 and 2019) warrants further inquiry into its origins – to which I now turn.

TWO MORAL ECONOMIES

Prior to 1989, state hegemony in Jordan was maintained through welfare institutions, employment inducements, price subsidies, and a developmentalist discourse premising the state as the buffer between Jordan and the vicissitudes of global capitalism.Footnote 26 As summarized by Greenwood, Jordan's social “bargain” – dating back to the nation's colonial founding under Emir Abdullah (r. 1921–1951) in the 1920s – “offered citizens economic security in exchange for their political loyalty (or at least acquiescence) to the Hashemite monarchy”.Footnote 27 The material inducements provided by the state, in order to mobilize society to productive ends and stave off social unrest, constituted two distinct, but related, moral economies. The first revolved around the provision and pricing of commodities – such as bread and fuel – while the second functioned through the intervention of the state as the most important conduit of national development and employment. Both of these moral economies were disrupted in the wake of neoliberal reforms beginning in 1989 and accelerating after King Abdullah's ascension in 1999.

The moral economy of commodities

Born out of the struggles between the British-controlled colonial state under Emir Abdullah and the pre-existing tribal communities of Transjordan, the moral economy of commodities became fully realized in the 1970s under King Hussein (r. 1952–1999).Footnote 28 As Martínez has demonstrated, the critical moment came with the establishment of the Ministry of Supply (MoS) in 1974, which did much more than centralize the “pricing and distribution” of basic goods (its raison d'être) but also embodied an “image of a managerial state that could intervene to combat the instabilities of capitalism”.Footnote 29 Almost overnight, the king began to reinforce this image by publicly articulating a “middle way somewhere between the nationalization of the means of production and the unregulated free market”.Footnote 30 The cornerstone of this “middle way” was the provision and distribution of Arabic bread (khubz ‘arabi) – along with a bundle of other basic commodities – at a reliably low price.

The moral economy of national resources

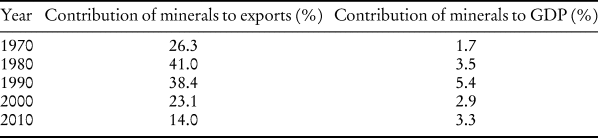

While Jordan lacks the oil reserves of its neighbours in Iraq and Saudi Arabia, natural resources – specifically phosphate and potash – nonetheless have constituted “the foundation for the enhancement of Jordanian private and public investments, modernisation of its infrastructure and the expansion of public services in health and education”.Footnote 31 In economic terms, the mining industry in Jordan (also including the extraction of cement and calcium carbonates) has significantly contributed to GDP and national exports since the 1970s (see Table 1). Finally, while the mining sector represents a relatively small percentage of total national employment, the sector has been qualitatively vital as a major employer and trainer of two important regime constituencies: educated workers (e.g. engineers and geologists) and Jordanians living in and around the main extraction and production sites.Footnote 32

Table 1. Economic Significance of the Minerals Industry in Jordan.*

* Potash and phosphate made up over two thirds of mineral exports in the 2000s, with cement making up the next largest percentage (ten per cent).

Source: Rami Alrawashdeh and Philip Maxwell, “Jordan, Minerals Extraction and the Resource Curse”, Resources Policy, 38 (2013), p. 106.

The connection between Jordanian national interests and natural resources is enshrined in the 1952 Constitution, which stipulates that “[a]ny concession granting any right for the exploitation of mines, minerals or public utilities shall be sanctioned by law” – that is, via parliament (Article 117).Footnote 33 Originally, however, through their 1928 treaty with Emir Abdullah, it was the British who first had the power to issue mineral concession rights in Jordan.Footnote 34 Consequently, British colonial priorities determined the initial pace of mineral exploration and the timing of the first mining concessions in Jordan (1935 for phosphate and 1930 for potash).Footnote 35 Later, in the 1950s, “nationalist bureaucrats” such as Hamid al-Farhan struggled with hostile American and British donors to secure the autonomy to develop the nation's resources (see Figure 1).Footnote 36 It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that a measure of resource autonomy was achieved, though Jordan's mineral concerns have always been supported, even proudly so, by high levels of foreign involvement, “from planning and implementation to financing”.Footnote 37 Following the civil war between the monarchy and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1970, state-provided employment began to skew disproportionately towards East Bank Jordanians, who, since the founding of the Hashemite monarchy in the 1920s, had constituted the state's most important social base.Footnote 38

Figure 1. Underground phosphate mining in Rusaifeh, Jordan in 1953. Photograph from a 1961 booklet. Accessed at Zaman.com, on February 2, 2021.

With these internal and external struggles in mind, we can read the following statement from King Hussein, regarding the state's massive investments in the exploitation of Dead Sea minerals for potash production in the 1970s, as articulating the (top-down) terms for the moral economy:

This project has special significance for our national growth and development. Its progress, after many years of hard efforts, delays, and difficulties, is great proof that we have assumed control over our national capabilities, and that we have set ourselves on the path of practical planning for our economy and that we are now able to mobilize qualified Jordanian youth to carry out the responsibilities of development […] The Arab Potash Project is a splendid model for our strife against backwardness and stagnation. It is a courageous and ambitious attempt at the utilization of our natural resources.Footnote 39

Given the symbolic and material importance of natural resource exploitation to state hegemony, as reflected in this statement, it becomes easier to piece together why, despite mounting domestic and international pressures in the 1980s and 1990s to privatize national resource companies, King Hussein remained reluctant until his death.Footnote 40

Jordan's moral economy of national resources is perhaps most physically embodied by the so-called Big Five companies – including the Arab Phosphate Company (APC) and the Jordan Phosphate Mines Company (JPMC) – which were first established as private enterprises in the 1950s.Footnote 41 Yet, the “poor capacities” of the private sector necessitated heavy state involvement from the very beginning.Footnote 42 By the end of the 1980s, the level of state intervention in these companies was significant and included ownership of controlling stakes and the ability to appoint and displace actors from company boards. For example, prior to its privatization in 2006, the JPMC was ninety per cent state-owned and its operations were conducted in “extensive” coordination with the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the Natural Resources Authority.Footnote 43 In return, from the 1970s, the mining sector (phosphate, potash, and cement) propped up Jordan's export sector.Footnote 44

Hence, beyond their importance to the economy, according to Piro, the phosphate and potash companies were positioned by the state as “symbol[s] of national will, development, and modernization”.Footnote 45 The national symbolic nature of these resources emanated from three central dynamics related to Jordan's status as a “late developing” country.Footnote 46 Firstly, resource exploitation required massive mobilizations of foreign and domestic capital on top of substantial investments in national infrastructure. These investments, in turn, were justified in terms of the national project to “modernize” Jordan.Footnote 47 Relatedly, the state-controlled enterprises provided employment for key professional-class workers, as well as Jordanians living in the otherwise economically overlooked mining regions.Footnote 48 For example, in the southern governorate of Ma'an, the development of the Al-Shidiyah mine in 1988 was followed by consistent increases over the following two decades in education and health indicators, as well as secular decreases in the unemployment and poverty rates (Figure 2).Footnote 49 Finally, mining employees, in return for their privileged place in national development (along with an array of material benefits), were pushed to submit to state-controlled unions.Footnote 50 Consequently, similar to khubz ‘arabi, the national resource-exploiting enterprises came to represent a material juncture through which historically constructed social pacts and multivalent understandings of legitimacy, distributive justice, and national development interfaced.Footnote 51

Figure 2. Distribution of phosphate and potash resources and facilities in Jordan.

FROM “BREAD RIOTS” TO PRIVATIZATION

While the moral economy of national resources remained largely sacrosanct until 1999, the economic crisis of the late 1980s marked a major disruption in the moral economy of commodities. From 1983, the global price of oil plunged and Arab foreign aid began to shift to Iraq (to aid in its war against Iran), jeopardizing the state's access to rents. Debt skyrocketed and the dinar lost thirty-five per cent of its value between November 1988 and February 1989.Footnote 52 This led Jordan to the doorstep of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whom “policy-makers considered the only source of relief”.Footnote 53 The resulting Standby Arrangement (SBA) with the IMF, signed in 1988 and implemented in 1989, was conditional upon the privatization of public sector investments, trade liberalization, cuts in state employment, and the removal of subsidies. However, for the first decade of structural adjustment, King Hussein was reluctant to go beyond modest price hikes, which were nevertheless met with widespread social unrest.

Despite the restrained nature of these reforms, “[w]ithin hours” of the 1989 IMF- mandated freeze of public wages, salaries, and hiring – coupled with increases in domestic petroleum prices – the largest protest wave in two decades erupted across Jordan.Footnote 54 Beginning in the southern city of Ma'an in April – a historical bulwark of regime support – protests quickly spread throughout the country. The social and spatial character of these “bread riots” signalled a dramatic shift in the nature of social protest in Jordan.Footnote 55 Historically, opposition to state polices sprung from the “usual suspects” of “leftist parties, Islamists, and/or Palestinian Jordanian activists”.Footnote 56 However, after 1989, opposition to state policies was increasingly characterized by the predominance of East Bank Jordanians. Indeed, many of my East Bank Jordanian interlocutors viewed 1989 as their political awakening. According to one activist from the southern city of Karak, this was the moment that “changed everything”: the Jordanian economy had “become naked”, newly exposed to private sector interests and foreign capital.Footnote 57

While 1989 represented a new and potentially existential threat to the prevailing order, King Hussein was able to stave off a unified national challenge to state power by quickly orchestrating a series of top-down reforms, including the lifting of martial law, in effect since 1967, and the revival, albeit limited, of electoral politics in Jordan. Additional “bread riots” erupted in 1996 and 1998, the trajectory of which largely conformed to Walton and Seddon's description of austerity protests as spreading “quickly and contagiously” and yielding “short-term successes” without disrupting processes of “long-term depredation and socio-economic restructuring”.Footnote 58 Hence, while the waves of unrest precipitated by periodic price hikes in the 1990s prefigured the social bases of the 2011–2013 uprisings in many ways, they also differed in important respects. The principal difference had to do with the political-economic context: according to Tariq Tell, “in contrast to 1989, neoliberal reform was now the policy of choice for the Palace, rather than a necessary expedient imposed by the IMF”.Footnote 59

To establish the new common sense underlying this neoliberal political economy, King Abdullah – in collaboration with Western governments and international financial institutions – began to articulate a new relationship between the state and its subjects: instead of state employees, citizens were increasingly encouraged to become “entrepreneurs”.Footnote 60 Instead of a welfare and job provider, the state was in “partnership” with the private sector in creating an attractive “business environment” for domestic and international investment.Footnote 61 At the same time, the king increasingly began to place control over economic policy into his own hands – and those of a small coterie of technocratic elites – effectively circumventing parliament and simultaneously cracking down on dissent from below.Footnote 62

The differences in the pace and scope of privatization under Abdullah II versus what came before were stark. In the 1990s, the state owned controlling shares in 109 enterprises; by the mid-2000s, the government had divested from over forty of these enterprises, including the JPMC and APC.Footnote 63 This acceleration of privatization, however, did not mean that the state had completely lost sight of its moral obligations. According to the government's own (post hoc) study of privatizations, undertaken between 2013 and 2014, privatization was not considered an unalloyed good – it was, rather, “a means and not an end in itself”, the benefits of which “are numerous if the process is implemented in an environment of transparency, competitiveness, and accountability”.Footnote 64 By these standards, the Privatization Evaluation Committee (PEC), under Omar Razzaz (who would become Prime Minister in 2018), criticized the implementation and results of a number of privatizations – in particular the 2006 privatization of the JPMC.Footnote 65

According to the PEC, the JPMC privatization had “lacked many transparency standards and [a] commitment to best practices”.Footnote 66 It is thus worth examining this privatization in more detail. The JPMC was sold under opaque circumstances, ostensibly to Brunei – via Kamil Holding Ltd – though many of my interlocutors believed this to be a smokescreen for the real buyers in the king's own circle.Footnote 67 Indeed, Walid el-Kurdi, the brother-in-law of the late King Hussein, “was personally involved in the process of the privatization” and became the head of the company in 2006.Footnote 68 Thus, for many Jordanians, the JPMC “was not privatized but rather taken over by the Hashemite monarchy”.Footnote 69 By contrast, the privatization of the APC in 2003 conformed more closely to the PEC's definition of “best practices”, including enhanced transparency, and was, correspondingly, viewed by many of my interlocutors in a more favourable light.Footnote 70 In order to untangle the social consequences of these different privatizations, in what follows I trace the protests as well as narratives of corruption and theft employed by differently situated activists in Jordan between 2011 and 2013.

PRIVATIZATION AND ARTICULATING RESISTANCE IN JORDAN

On a sunny May afternoon in Amman in 2012, a protester holds a sign overhead among a sea of demonstrators: sketched on one side is an outline of a map of Jordan with the word “SOLD” in English stamped over it in red; written on the other side is a list of privatized companies: “The Phosphate company, the Potash company, the Jordanian Communication, the Jordanian Cement company, the Dead Sea beaches, and Aqaba beaches, the Port of Aqaba, the Jordanian industrial city.”Footnote 71 This sign (and many others like it) articulated a sense of illegitimate redistribution: privatizations are corrupt; they represent the end of the public sector as a source of livelihood in Jordan; and they are equivalent to “selling” off the country (and Jordanians’ birthright). The protest chant quoted at the top of this article draws these different sentiments together: “Out, Out, Corruption! … We want Jordan to stay free!”

Between 2011 and 2013, over 8,000 protests, marches, and strikes swept across Jordan, responding to decades of economic immiseration and stalled democratic reforms.Footnote 72 In addition to their scale, these mobilizations were unprecedented in Jordan because of the participation of groups from across the country, including the “traditional” opposition (the Muslim Brotherhood and opposition parties), as well as two new social movements: a new independent labour movement and the Hirak. The Hirak (or “movement”) “encompassed nearly forty East Bank tribal youth activist groups across the kingdom, representing rural communities long thought to be unflagging supporters of the autocratic regime”.Footnote 73 In this section, I demonstrate how labour and non-labour activists shared an understanding of privatizations rooted in moral economy, which served as the basis for a shared discourse of resistance to neoliberal reforms. In this way, privatization created the possibility for a broad-based and transgressive national discourse – albeit one that ultimately fell short – representing, as one activist put it, a new “genetics” of resistance in Jordan.Footnote 74

Privatizations connected the daily experiences of immiseration and deprivation under structural adjustment to the (failed) promises of national development as symbolized, in large part, by Jordan's national resources. In the eyes of Hirak activists, public assets belonged to Jordanian citizens, and their “theft” was akin to “losing everything”. As one activist from Amman put it:

We would like to know where all that money is spent because they took that money from privatization projects. It didn't work out. I didn't sense it on my salary, I didn't sense it on my lifestyle, I didn't see it on the transportation system, the health, my education, [and] the youth are still taking loans and paying for their own salaries to the universities. […] It didn't reflect on our lives. It was a huge mistake by the governments to do this and we didn't get any benefits […] In the airport, the Port [of Aqaba], and our two big companies [the Port and Phosphate] unfortunately we sold more than 30% of them. This is what it feels like when you talk about the privatization. We lost everything.Footnote 75

Whether or not Jordanians felt the outcomes of privatization “in their pockets” therefore gets to the heart of how privatizations in Jordan were experienced: as a betrayal of the state's distributive obligations and the failure of neoliberal reforms to make life better.

This shared sense that expectations of redistribution had gone unmet transcended divisions across society: from the local to the national and across labour and non-labour movement constituencies. This prompted a turn towards innovative forms of grievance articulation. As a prominent labour and Hirak activist explained:

The [Prime Minister in 2011] Rifai government waged war on unions. Union leaders were imprisoned, fired, or relocated to distant sites for having organized strikes. These transfers made us think of new ways to struggle for change: using protests and echoing people's grievances about the government, such as economic policies that raised the prices of basic goods used by the poor, increased unemployment and poverty. So we founded the Jayeen movement. We organized demonstrations all over the country, calling for a new national unity government. We have also demanded a special tribunal against the corrupt individuals who sold national assets such as phosphate mines, transportation, and water [by granting foreign companies exclusive mining and management rights] at prices that didn't reflect their value.Footnote 76

The protest movement alluded to in the above quote, Jayeen (“we are coming”), was in many ways emblematic of the “new ways to struggle for change” emerging in Jordan. Bringing labour and Hirak activists from the governorates to the capital city, Jayeen was a major participant, along with a loose confederation of other organizations, in the largest protests of Jordan's 2011–2013 uprisings under the umbrella of the “March 24 [2011] Movement”.Footnote 77 As Bouziane and Lenner emphasize, 24 March represented an unprecedented attempt “to form a broad coalition for substantial political and economic reforms, transcending potential divides between different population groups” – though one that ultimately failed in the face of state repression and divisions within Jordanian society.Footnote 78 Despite the dissolution of Jayeen shortly thereafter, there were myriad other protests, strikes, sit-ins, and public demonstrations that brought Jordanians together, united around narratives of theft and corruption. That these struggles all featured specific and emotive references to privatizations speaks to the power of national resources as a national symbol.

Ambivalence and legitimacy

Key to these narratives was a shared perception of legitimate practices of redistribution. It was not simply that state-controlled companies had changed ownership (from public to private hands), but, instead, that illegitimate privatizations were seen as denying to Jordanians the fruits of their national resources, for example, to national development, basic subsistence, and/or employment. These sentiments were echoed in a highly influential “economic communique” released by the National Committee for Retired Servicemen (NCRS), a dissident movement of retired East Bank military veterans. In the document, which targeted “the privatization of the public sector” and the “restructuring of the state”, the NCRS accused a “small number of influential people” in the government and private sector of “sell[ing] the people's property, including companies, institutions, natural resources, capabilities, lands, [and] infrastructure”.Footnote 79 While critiques of the NCRS rightly point out the East Bank nationalist undertones of the communique, I argue that, as a symbolic representation of state–society relations in neoliberal Jordan, privatizations were capacious and multivalent, and thus resist reduction to any single interpretation.Footnote 80

Rather than simply an expression of nationalist chauvinism, the moral economy of national resources reflected a shared sense of illegitimacy in the way many privatizations were carried out. Indeed, accusations of theft and corruption often came from those who professed to see the value in the privatizations (“I am not against privatization” was a common refrain) – even when assets were sold to foreign entities. In the words of one Hirak activist: “I support the idea of privatization […] the question is not about privatization or not, but how do they spend the money?”Footnote 81 In this sense, activists’ perceptions of privatization mirror Jordanians’ perceptions of good, tolerable, and corrupt forms of Wasta, or “local practices of political patronage and favouritism”; as Doughan has argued, Wasta “constitutes a problem only when it provides differential access to common resources managed by the state or by some other corporate entity such as a private or public corporation”.Footnote 82 Though always somewhat ambivalent, what mattered, in other words, was the perception of legitimacy. The privatization of the JPMC is instructive in understanding this distinction.

Revolt of the workers

In 2006, when the JPMC was privatized, the brother-in-law of the late King Hussein, Walid el-Kurdi, was subsequently installed as CEO. His corrupt tenure, and its effects on JPMC workers, came to a reckoning in 2011, when el-Kurdi's son's pay stub – displaying a five-fold increase over those in similar posts – was circulated to workers.Footnote 83 The pay stub had the effect of galvanizing phosphate workers around the issue of corruption, precipitating two general strikes between 2011 and 2013. These events ultimately led workers to break away from their official trade union, The General Trade Union of Mines and Mining Employees (GTUMME) – one of the seventeen officially permitted trade unions belonging to the General Federation of Jordanian Trade Unions (GFJTU).

Fioroni's detailed ethnographic exploration of the JPMC employees demonstrates how the privatization of the JPMC created various, even conflicting grievances among the employees.Footnote 84 On the one hand, the professional-class strike organizers were motivated by their belief that the privatization had failed to produce a rationalized, meritocratic corporation. On the other hand, those in the non-professional stratum of employees were aggrieved by the newly privatized JPMC's failure – due to el-Kurdi's circumvention of long-established clientelist recruitment/advancement practices in favour of his own – to live up to its historical obligations regarding the distribution of permanent jobs to those living in the mining regions. Because the strike leaders required the participation of those living and working in the mining regions to shut down the mines, they consciously drew upon mutually comprehensible and salient aspects of the privatization – the “corruption” of employment practices, the “theft”/privatization of the company, and de facto royal family control – to rally a broad base of workers.Footnote 85

Consequently, in April 2011, a group of about thirty JPMC employees initiated a three-day sit-in against their union, “denouncing corruption and mismanagement, asking for new [union] bylaws, a new personnel system, and the fair treatment of employees”.Footnote 86 Initial responses to the sit-in came from both the GTUMME, which declared the sit-in “illegal and illegitimate” (because protesters were circumventing the union), and Walid el-Kurdi himself.Footnote 87 At first, el-Kurdi attempted to assuage workers’ concerns by signing a vague agreement with them. Instead of relenting, however, the organizers of the April sit-in proceeded to initiate two general strikes between 2011 and 2012 and, in June 2011, they established a new independent union – becoming the first workers to exit the formal GFJTU structure.Footnote 88 The first strike, in June 2011, involved a massive organizing effort and brought together “employees from all the production sites, high skilled and low skilled employees, and employees from diverse tribal and local origins”.Footnote 89 Notably, the strike resulted in the shutdown of all three phosphate mines. During this period, the demands of phosphate workers expanded from their specific grievances focused on the JPMC's management, remuneration, and organization following the 2006 privatization, to criticisms of the official union structure, as well as the entire Palace-led privatization project.Footnote 90

As expressed by one of the leaders of the movement, the motivation for these actions stemmed from the illegitimate way in which the privatization had been conducted:

Our movement it wasn't against the privatization. It's against the way Walid el-Kurdi is acting and stealing the company. […] [We were] asking for accountability, government accountability. To audit the finances of the company. […] They stole the phosphate and did not privatize the company.Footnote 91

Thus, their grievances were in opposition to the state-articulated “common sense” that privatizations were a necessary step towards prosperity. At the same time, workers’ demands transcended el-Kurdi as an individual by framing el-Kurdi's “theft” in terms of the corruption of the state (the “they” in the above excerpt).Footnote 92 In response to the first strike wave in 2011, the regime eventually stepped in:

[After the May 2011 strike] [s]ome senators from the parliament, they contacted us, and the administration of the company, to solve the problem. And we signed an agreement with the senators – on one condition: that the parliament would establish a committee to investigate the privatizations. And we established our independent trade union.Footnote 93

The establishment of the commission to investigate the privatizations – and the resulting 2014 report – became a point of significant pride for the leaders of the independent phosphate union.Footnote 94

Beyond the JPMC workers’ movement, the privatization of the company was articulated to, and resonated with, differently situated actors across Jordan – exemplifying the discursive power of the moral economy. Firstly, in the mining regions, the privatization had a mobilizing effect among unemployed job-seekers whose expectations of resource distribution through gaining jobs in the JPMC had been stymied by the hiring freeze. Specifically, though the hiring freeze pre-dated the privatization, it was both kept in place under el-Kurdi and compounded by el-Kurdi's periodic and conspicuous employment of his family members. Consequently, young job-seekers demonstrated in 2011 to protest the company's failure to live up to its historical obligations to distribute jobs in the regions in which it extracted mineral wealth.Footnote 95 Secondly, by bringing to light the overt corruption and nepotism on display in the JPMC privatization, the JPMC workers created common cause with the Hirak. For instance, in their own enumeration of grievances, Hirak activists frequently echoed the phosphate workers’ claims that the JPMC was sold under mysterious circumstances and at an insulting price.Footnote 96 El-Kurdi's name was also commonly evoked in the demonstrations that filled the streets of Amman and across the governorates throughout the 2011–2013 period.Footnote 97

Unravelling “illegitimate” privatizations

As previously alluded to, recent scholarship on Jordan has suggested that Jordanian's resistance to privatization was motivated by nationalism, against either “Palestinians” or foreign capital.Footnote 98 In this framing, anti-privatization sentiments by East Bank Jordanians were merely a defensive ploy to regain lost patronage benefits. Evidence for this argument includes protesters’ focus on Queen Rania and her family (who are of Palestinian descent) as among the most corrupt.

Ababneh, by contrast, has argued that resistance to privatizations was fuelled, in part, by the perceived loss of Jordan's “economic sovereignty” to international financial institutions and foreign multinational corporations.Footnote 99 However, anti-corruption slogans also targeted figures such as Omar Ma'ani, the disgraced Transjordanian former mayor of Amman and architect of the city's neoliberal transformation after 2006.Footnote 100 Moreover, if the issue were solely nationalist (either Transjordanian or Jordanian), the fact that a Canadian firm bought the APC would not have passed without much remark from many of my interlocutors.Footnote 101 Indeed, the APC privatization was often contrasted against the more negative experience of the JPMC:

[I]n the potash company, after the Canadians came and they bought the shares from the government, the situation was completely different than the phosphate company. Why? Because [the potash privatization] worked very well. They made very good bylaws and they provided good benefits […] And in the phosphate it's the complete opposite. I told this to Walid el-Kurdi face to face.Footnote 102

While other activists felt both privatizations were illegitimate, these differences, in my discussions with activists, reflected ambivalence more than chauvinism.

In sum, Hirak slogans and signs frequently called for the prosecution of the “thieving corrupt ones” (fasadeen haramiyya), a class-based, more than an ethnicity-based, designation, which encompassed many Jordanians of Palestinian descent but also plenty of East Bank elites.Footnote 103 That some activists were willing to entertain the idea of privatizations suggests that the salient issue was not privatization per se, but whether national resources had been put towards the collective good.Footnote 104 Moreover, the consequences of these thefts were felt both materially – for instance when potash workers in Karak lost their jobs – and more symbolically and nationally, as a moral violation by the state.Footnote 105

Beyond the “economic” and the “political”

Privatization thus served as the prism through which corruption, capitalist exploitation, unemployment, and illegitimate exploitation of national resources could be understood by activists as interconnected. This belied yet another neoliberal “common sense”, namely, that economic reforms should be de-politicized and delegated to the designs of technocrats.Footnote 106 Moreover, in contrast to the moral economy of commodities, the violation of the moral economy of national resources could not be as easily resolved or deferred by, for example, rolling back prices.

Privatization was much more hardwired into the circuits of global capitalism. To roll back privatizations would mean reversing the flow of upward redistribution (and foreign capital) that neoliberalism is predicated upon. The best state actors could do was to project all of society's grievances vis-à-vis privatizations onto a few sacrificial elites, such as Walid el-Kurdi. This strategy mirrors Lyall's description of Ecuadorian elites’ attempts to position themselves as “moral managers” of national resources through anti-corruption campaigns.Footnote 107 However, doing so could not turn back the clock on the articulation and spread of transgressive discourses. This was relayed quite concisely to me by a Hirak leader from a northern Amman neighbourhood: “it's all politics and economics, [they are] two faces of one coin”.Footnote 108 For their part, labour activists also saw that the continuing suffering of workers was wrapped up in the policies of the state:

In the economic path, [the] plans they are making, […] when it's wrong, the workers will pay the price. When the political policy is not right, also the workers will pay the price. For these reasons, you can't separate things.Footnote 109

This kind of discourse, traceable in part to the violation of the moral economy of national resources, brought diverse movement constituencies together around the realization that political and economic conditions and grievances were all intertwined – transcending place and ideology.

The work of articulation occurred reciprocally between labour and non-labour movement constituencies. Between 2011 and 2013, labour and Hirak activists, by making the “connection” between economic and political struggles, necessarily moved beyond “restorative” demands to articulate a systemic critique of the neoliberal authoritarian state. Through active efforts to merge labour and popular demands – such as the Jayeen movement (see above) – workers brought their grievances to the protest square, which were then picked up and further articulated by Hirak demonstrators. As one activist explained to me, “yes, we started with economic demands, but they realized for all those demands, the solution is politics; we started with economic demands and we find out that the solution is political and so our demands became political – we want a parliament because we want a voice”.Footnote 110 He further clarified the role of the Hirak: “we gave to [the worker movement] a social aspect that is much more political; we understood privatization as a social problem (our economy, our companies)”.Footnote 111

In making such pronouncements, activists also decried the inadequacies of previous “political” avenues of change, such as the top-down reforms of 1989, or of Abdullah's “economic” path – vis-à-vis promises of modernization and economic prosperity.Footnote 112 The former had proven sufficient merely to perpetuate the status quo (e.g. the moral economy of commodities), while the latter, through neoliberal reforms such as the privatizations, had actually made life for many in Jordan considerably worse while delimiting civil rights in the process. It was in response to the failures of both the 1990s and the 2000s that some activists began to elaborate a systemic critique of the entire “situation” in Jordan. As one Hirak activist summarized: “[m]ainly it is the economic system, it is the privatization that we fight so much against, the capitalist economic system in Jordan”.Footnote 113 Moreover, it was in the context of the uprisings that “neoliberalism” became a “new phrase” in activist circles.Footnote 114 In a discussion with an activist leader from Amman, he explained to me that in the 2000s, “new faces” came into power – “the neoliberals” – who “sold everything”; he added that “you cannot survive if they are selling off all your resources”.Footnote 115

While the societal extent of such sentiments requires further research, the fact that they were expressed by differently situated actors – across labour/non-labour, urban/rural, and other social divides – demonstrates that grievances surrounding privatizations resonated with a significant cross-section of Jordanians. In part, this was due to the fact that national resources were inextricably tied to historical state obligations of economic redistribution (e.g., through jobs and state welfare). Labour activists emphasized narratives of “theft” and “corruption” in articulating resistance to privatizations in order to win over broader worker and social support. In reciprocal fashion, Hirak activists performed the discursive work to reframe privatization as a “social issue” impacting all Jordanians – not just those who worked at privatized companies – because, in the view of one such activist, “the Hirak is not a political project, it's a political experience, a political voice; Hirak, whatever it represents, it's from the people and for the people”.Footnote 116 Together, these and similar articulations reflected activists’ comprehension of the structural connections between their lived material experiences and the policies of the neoliberal state, which had been made visible through the prism of illegitimate privatizations and the moral economy of national resources.

CONCLUSION

As argued in this article, privatization necessarily means more than simply a change in asset ownership from public to private. In Jordan, privatization was experienced by many activists as an instance of “accumulation by dispossession”, or, in other words, the “reversion to the private domain of common property rights won through past class struggles”.Footnote 117 Hence, the narratives of theft and corruption employed by my interlocutors reflected the perception that the fruits of Jordan's national resources belong to Jordanians as part of historical state–society pacts won through social struggle, the abrogation of which – through illegitimate (corrupt, opaque, and poorly planned) privatizations – constituted a moral violation. In this article, I have argued that the privatization of the commons in Jordan precipitated the development of a new, transgressive framing discourse of protest, which created the possibility for a national-scale movement to resist the state's neoliberal project. Yet, this discourse was only able to go so far. By 2013, the state had succeeded through the strategic use of material and political concessions and violence to demobilize and demoralize the resistance.Footnote 118 Nevertheless, through the privatization of the commons, King Abdullah II's accelerated neoliberal project has ushered in a new era of contentious politics, one that has reverberated in recent mass protests and strikes over the last two years, as many Jordanians continue to challenge the terms of neoliberalism and, by extension, authoritarianism.Footnote 119