Introduction

On Monday 17 September 1921 the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition left England on the tiny R.Y.S. Quest, its purpose to circumnavigate the Antarctic continent, during which it would conduct an ambitious marine research and survey programme, and also search for some “lost” or wrongly charted sub-Antarctic islands. The story is admirably recounted by Frank Wild (Reference Wild1923) in his book Shackleton's Last Voyage. The Story of the “Quest”, based largely on the personal diary of the expedition doctor and surgeon, Alec Macklin.

It is well-documented that Sir Ernest Shackleton wanted to appoint a cabin boy who had already proved himself in outdoor pursuits and with a potential to lead others – a sort of apprenticeship, which would stand in good stead for his future career. To this end, Shackleton appointed two Boy Scouts, James W.S. Marr and Norman Erlend Mooney. Much has been written about Marr, who devoted his life to an Antarctic career (Fisher & Fisher, Reference Fisher and Fisher1957; Marr, Reference Marr1923; Wild, Reference Wild1923; The Scout Association Archive (SAA) (www.scoutsrecords.org/exhibitions, see Explore - Exhibitions Archive 2010--2012, RSS Discovery); “Johnny” Walker's Scouting Milestones (JWSM) website (history.scoutingradio.net/marr.htm)). However, these accounts make only passing reference to Mooney, notably because he had to return home shortly after sailing because of severe seasickness. This account provides some detail of Mooney, and an insight into Shackleton's motive to appoint the Boy Scouts and his sensitivity in the selection process.

Appointment of Boy Scouts for the expedition

Shackleton considered that the addition of a Boy Scout to his crew would attract press attention and capture the public imagination. In his quest to appoint a cabin boy he wrote to Sir Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scout movement, on 9 July 1921: “For many years, I have been an admirer of the Boy Scout Movement, which I may say appeals to me particularly because it seems to give every boy a grounding in the practice of exploration” (JWSM website, but origin unknown). Baden-Powell's response was that he was very much in favour of such an honour being bestowed on a member of the Scout organisation, having often referred to stories of British heroism as exemplified by British explorers, including Scott and Shackleton. He agreed to provide Shackleton with the names of appropriately qualified boys from which he could select a Scout to accompany the expedition. Furthermore, on Baden-Powell's advice, Shackleton approached an enigmatic Roman Catholic priest, Rev. Father J.E. Rockliff, to recommend suitably qualified Scouts for the position. Rockliff had an unusual background, including being a master mariner in the Merchant Navy, commander of a troop carrier to South Africa during the Boer War, naval chaplain with the Grand Fleet in the First World War (Battle of Jutland), marine scientist, authority on earthquakes, Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Boy Scout Commissioner, radio broadcaster, multilinguist and world traveller. Little is known about Father Rockliff besides what appeared in newspaper articles during his travels, notably in Australia and New Zealand. Besides being a Scout Commissioner for Orkney he had a personal connection with Baden-Powell from his involvement in the Boer War. Rockliff played an important role in the (somewhat biased) recruitment of the “Expedition Scout” by sponsoring the applications of two Orcadians from the 2nd Orkney Troop (Patrol Leaders Norman Mooney and W.L. Warren) (JWSM website; personal archive of Warren's family).

On 9 July 1921 the position of cabin boy was duly announced by the Secretary of the Scout Association, Major A.G. Wade, in the Daily Mail (which gave much publicity and sponsorship to the expedition). Originally, six Scouts were to be called to interview, but as the quality of the applicants was so high Shackleton increased this to ten. The ten interviewees, selected from ca.1,700 applicants by Baden-Powell himself, received a handwritten postcard from The Boy Scouts Association, Imperial Headquarters, London, inviting them to present themselves for the final selection a week hence (Letter from A.R. Stokes to Mooney, 8 August 1921, A. Mooney Archive):

Dear Scout,

You have been selected by the Chief Scout with 10 others [actually, nine others!] to come to London for the final selection of a Cabin Boy to accompany Sir Ernest Shackleton. Please hold yourself in readiness to come to London at short notice some time after Thursday next.

A. R. Stokes

On 11 August Shackleton wrote to Baden-Powell that he wished to see the dossiers of the Scouts before he interviewed them individually, stating also of the successful candidate, “I do trust he will do well and be an example to the wonderful Organisation inspired and directed by you” (SAA website). The ten candidates were interviewed on 17 August, and after much deliberation Shackleton chose two Scouts with such exceptional credentials that he couldn't choose between them. One was Patrol Leader James William Slessor Marr (aged 18) of the 1st Aberdeen Grammar School Scout Troop, and the other was Patrol Leader Norman Erlend (his preferred name) Mooney (aged 16½) of the 2nd Orkney Scout Troop in Kirkwall (Fig. 1). For Mooney, this was the first time he had travelled beyond his home island. Immediately, Marr and Mooney were in contact with each other, and they visited each other's homes. Coincidentally, John Charles Bee-Mason, whom Shackleton appointed as official photographer and cinematographer to the expedition, was a voluntary training instructor at Gilwell Park, the home of the Scouting Movement (British Film Industry ScreenOnline website (www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/1266258/); JWSM).

Fig. 1. Norman Erlend Mooney and James W.S. Marr.

Shackleton wrote to Erlend's mother, welcoming him as a member of the expedition and providing information regarding his personal requirements and allowances. He dictated the content to his wife, Emily Shackleton, who wrote (Letter from Shackleton to Mrs Mooney, 28 August 1921, A. Mooney Archive):

Dear Mrs Mooney,

This is the first opportunity I have had, since I appointed your son, as one of the Scouts on the expedition, to write to you.

I hope and trust, indeed I feel that he will uphold the honour of the Island, and the traditions of that great movement to which he belongs, and also be a credit to the expedition.

You can well realise how difficult it was for me to make a choice amongst so many boys of good qualifications. It will interest both his father and you to know that the deciding factor in his favour was a certain modesty and reticence, combined with what appeared to me a nature capable of assimilating experience, and “growing big, in the bigness of the whole”.

Your son will not merely be a cabin boy. He will steer and stoke, and do sailor work, like all the other members of the expedition. He will live with the other officers, and assist particular scientific officers in their work, in whatever direction I find most suited to his capabilities.

As there is a good general library on board, his education will be furthered during the time he is with the expedition. I would like you to understand that his job will not be a mere “fetch and carry” one!

Regarding clothing, as far as I can see he will wear his scout uniform until we reach cold weather.

All his cold-weather equipment and clothing (including underclothing) I am providing for.

Pyjamas, light underclothing, cotton shirts and any old civilian clothing can be taken; there is no “dressing up” on the ship. He should have one good scout uniform and kit, for going ashore at Madeira, Cape Town, New Zealand, Australia, and South America. He naturally brings his own tooth brushes, washing gear, and 2 or 3 towels – soap is provided.

He may take an ordinary size cabin trunk – or small tin trunk, in addition to his kit bag – whichever you like – of course there will be room for any little personal things you like to give him, as there is a locker by his bunk. Lady Shackleton suggests you should put in a pillow – not larger than 22 in. by 18 in. – and 2 pillow cases (marked!).

Money - He will require no money, excepting his fare to London, for he will be paid, at the rate of £1 a week whilst on the expedition, and if he requires, when ashore, and [in] a foreign port, any money for a specific object I will advance it, subject to being satisfied with the object for which he deserves it.

Your boy should hold himself in readiness to leave home at 24 hour's notice – after the 4th September. Mr Rowett has very kindly arranged for both the Scouts to stay at his agent's house – at Ely Place, Frant, Sussex. They will come up to their work daily, and return in the evening to the country.

I do not expect to sail till the 11th or 12th September, but I think it advisable that the boys should get used to the ship before starting. Lady Shackleton (who is writing this for me) says she knows of course how much you will miss your boy, but I have assured her that if my rationale of his nature is correct he is certain to have a good time. For your further information, you will be kept advised throughout the expedition as to his progress.

With kind regards to Mr. Mooney and yourself. I am

Yours very truly,

E.H. Shackleton [signature]

On their appointment, Baden-Powell wrote to Marr and Mooney (JWSM website):

My Dear Scouts,

I want, in the first place, to congratulate you, as no doubt hundreds of others have done, on your selection by Sir Ernest Shackleton as members of the great ‘Quest’ expedition: and, secondly, I want to ask you to remember that far away you will be the centre of a world-wide interest on the part of not only your brother Scouts, but of everybody who believes in, or does not believe in, Scouts.

Preparations for departure

The two Boy Scouts received much media attention, presenting themselves well as ambassadors of the organisation they were representing, as well as the youth of the nation. In a newspaper interview (Inverness Courier, 23 August 1921) Mooney stated his main reason for wishing to go on the expedition as “The pleasure of serving a British hero, whether in difficult or ordinary tasks, and willingness to undertake and try to perform well whatever makes me generally useful.” Mooney was a quiet, somewhat reticent youngster, of slighter build than his fellow Scout, Marr. He was described, in an article in The Orcadian newspaper (15 September 1921), thus: “although he is a modest young man, there is something manly and respectful about him”. Their interviews and photographs appeared in national daily newspapers as well as in boys’ magazines (e.g. The Graphic, Chums and Young Britain). The front page of the weekly magazine Young Britain (No. 122, 8 October 1921) carried a conceptual image of “Quest” amongst towering icebergs, and the headings “Scouts of ‘The Quest’” and “Their Life Stories – commence today”, with separate insets of Shackleton, and of Marr and Mooney. A five-page article about the Scouts was accompanied by photographs of the boys and messages to Brother Scouts from them. Shackleton arranged with the editor of the magazine for the two Scouts to send him exclusive messages describing their great journey to the Antarctic. The magazine ran such articles for the next ten issues. As a result of their newspaper and magazine coverage Marr and Mooney became instant celebrities in an age when ordinary boys rarely achieved public acclaim.

The Scouts also received gifts from several sponsors of the expedition (JWSM website). Pursers and Sons, watchmakers to the Admiralty, gave them lever watches, and other gifts included special boots, cameras and fountain pens. The firms providing these could then advertise that their products were endorsed by Shackleton's Scouts. In addition, Mooney was presented with a copy of ‘The Poems of Robert Burns’ with an inserted bookplate “From The Burns Club of London to Patrol Leader Mooney of the Kirkwall Boy Scouts and the Shackleton Antarctic Expedition, 1921. Wishing him well in his great adventure. London – August 22, 1921.” (Item in A. Mooney Archive). Two weeks after their appointment Shackleton received a Scout flag from B-P to pass on to the boys. This was to be presented by them to the recently formed Boy Scout Troop on Tristan da Cunha, when Quest called there during the expedition (Marr, Reference Marr1923). On 10 September Shackleton wrote to Baden-Powell, “My dear Sir Robert, Many thanks for your kind letter. I will have the enclosures sent on to Marr & Mooney. I hope the two will do well, it is a great chance for them. In haste, Yours sincerely, E.H. Shackleton” (SAA website). The “enclosures” probably included the Scout Flag.

Departure of the Quest was delayed several times, during which Marr and Mooney stayed as guests of John Quiller Rowett, a wealthy rum importer and close friend of Shackleton, who financed the expedition. On the day of departure (17 September) Father Rockliff presented Erlend with a silver-plated bugle (provided by J. Ward & Sons, ‘Manufacturers of the Celebrated “Anzac” Band Instruments’) (Item in A. Mooney Archive).

Departure, seasickness and return home

As Quest sailed out of St Katherine Docks on the Thames, Mooney sent a wireless message to the Daily Mail (which had been covering the Expedition's preparations): “Many thanks for all your kind wishes. Tell the boys of Scotland and England to keep the Scouts’ flag flying.” (JWSM website).

After a 24-hour call at Plymouth to pick up Shackleton (Fig. 2), the expedition headed south but very shortly ran into bad weather crossing the Bay of Biscay. Erlend and another crew member, John Charles Bee-Mason, were severely ill. This mal de mer continued ceaselessly. Alec Macklin, the expedition doctor/surgeon, in his personal diary (author's copy), commented on 3 October “Of the Boy Scouts, Marr is doing very well & carrying on cheerfully – Mooney on the other hand has been so sea-sick & miserable that he has not been of much use. The same is practically true of Bee Mason.”

Fig. 2. The Boy Scouts Norman Erlend Mooney and James W.S. Marr with the crew of R.Y.S. Quest.

Quest spent 4–11 October in Lisbon for engine repairs and taking on provisions. Here, Macklin discussed the lads’ condition with Shackleton and it was decided that, for their own good, they should not continue on the expedition beyond Madeira if there was no marked improvement in their health. Shackleton reported this to Rowett in a letter sent from Lisbon. Rowett immediately wrote to Mooney's mother (Letter from Rowett to Mrs Mooney, 10 October 1921, A. Mooney Archive):

I received a letter from Sir Ernest Shackleton from Lisbon this morning, telling me that he could not take the risk of taking him [Erlend] further than Madeira. It is unfortunate, of course, but there is nothing disgraceful in being sick!

I understand that Nelson and other great sailors were always more or less ill when it was rough at sea, and for a boy to be continually in this condition would be more than he could stand. I have spoken to the Boy Scout Association here, and I am quite sure that your son will receive every sympathy and consideration. This will be the general feeling of the public, I am sure.

Between Lisbon and Madeira the weather improved, but the two youngsters continued to be critically seasick. Quest arrived at Funchal on 17 October and Macklin wrote to Shackleton “Norman E. Mooney has suffered severely from sea-sickness, which has produced great depression & inability to work. I do not consider him fit for the conditions likely to be met with on this Expedition, as a prolonged spell of bad weather with consequent sea-sickness is likely to produce exhaustion, & liability to more severe illness” (Letter from Macklin to Shackleton, 17 October 1921, A. Mooney Archive).

In his book, Marr (Reference Marr1923) made several references to Mooney's sufferings and expressed great concern and sympathy for his ailment. He commented remorsefully “Poor Mooney . . . . showed all the best characteristics of the best sort of Scout, and there was not the slightest fault attaching to him in his inability to endure the rigours” (p. 41). Similarly, Wild (Reference Wild1923, p. 32) was also very complimentary about the two young men: “. . . . this decision to send them back carries with it absolutely no stigma, for they showed extraordinary pluck and bore their trials uncomplainingly. To Mooney especially, a young boy gently nurtured, who had never before left his Orkney home, this portion of the trip must have meant untold misery. We greatly regretted losing both these companions.”

On the day of Quest's departure from Funchal (19 October) Shackleton sent a telegram to Erlend's parents, informing them of his return home: “. . . . Regret necessary action solely in Boy's interest. He was always willing.” (Telegram from Shackleton to Mooney, Kirkwall, 19 October 1921, Orkney Archives Ref. D49/1/3).

And so, with great disappointment, Norman Erlend Mooney returned prematurely to London, and thence to Orkney.

Several months later Erlend's father wrote to Rowett enquiring about unpaid salary, but it transpired Erlend was not entitled to this as three months’ notice had not been given. This rather miserly and blunt response seemed most unfair, considering the circumstances. Rowett wrote (Letter from Rowett to Mr Mooney, 13 February 1922, A. Mooney Archive):

It was very unfortunate that your son was so sea-sick, but nobody could help this, and Sir Ernest Shackleton was the first to recognise that the boy was absolutely unsuited on account of his unfortunately not being a good sailor.

The cheque I sent, I feel would cover the expenses which I understood from the Secretary of the Expedition he had put himself to in railway fares, but, as you say, he was not entitled to pay, in lieu of three months' notice. I think the best way out of the situation is to ask you to accept the cheque which I sent in re-payment of any expenses which you may have been put to.

I trust your son will soon have a very successful career . . . .

After hearing the news of Sir Ernest's tragic death at Grytviken, South Georgia, on 5 January 1922, Mrs Mooney sent a letter of sympathy to Lady Shackleton. In her reply Emily Shackleton wrote “. . . . I do thank you for all you said of my beloved husband. It touched me deeply. I hope Norman has quite got over all his bad times through illness. I sympathised very much with him. . . . .” (Letter from Lady Shackleton to Mrs Mooney, 18 April 1922, A. Mooney Archive).

Many months later, when the curtailed expedition returned to London, James Marr wrote to Erlend's father: “. . . . I was very sorry to lose his company. He was always a very pleasant companion. . . . . I was very sick practically all the way from England to Madeira & so were a large number of our company so that Norman need not worry himself on that account. I hope he is enjoying his new work. . . . .” (Letter from Marr to Mr Mooney, 3 November 1922, A. Mooney Archive). Considering that Macklin had noted in his diary that all but four of the ship's complement (including Shackleton) had been seasick prior to reaching both Lisbon and Madeira, it is perhaps surprising that Mooney and Mason were not allowed to continue. However, Macklin's and Shackleton's decision was probably the right one.

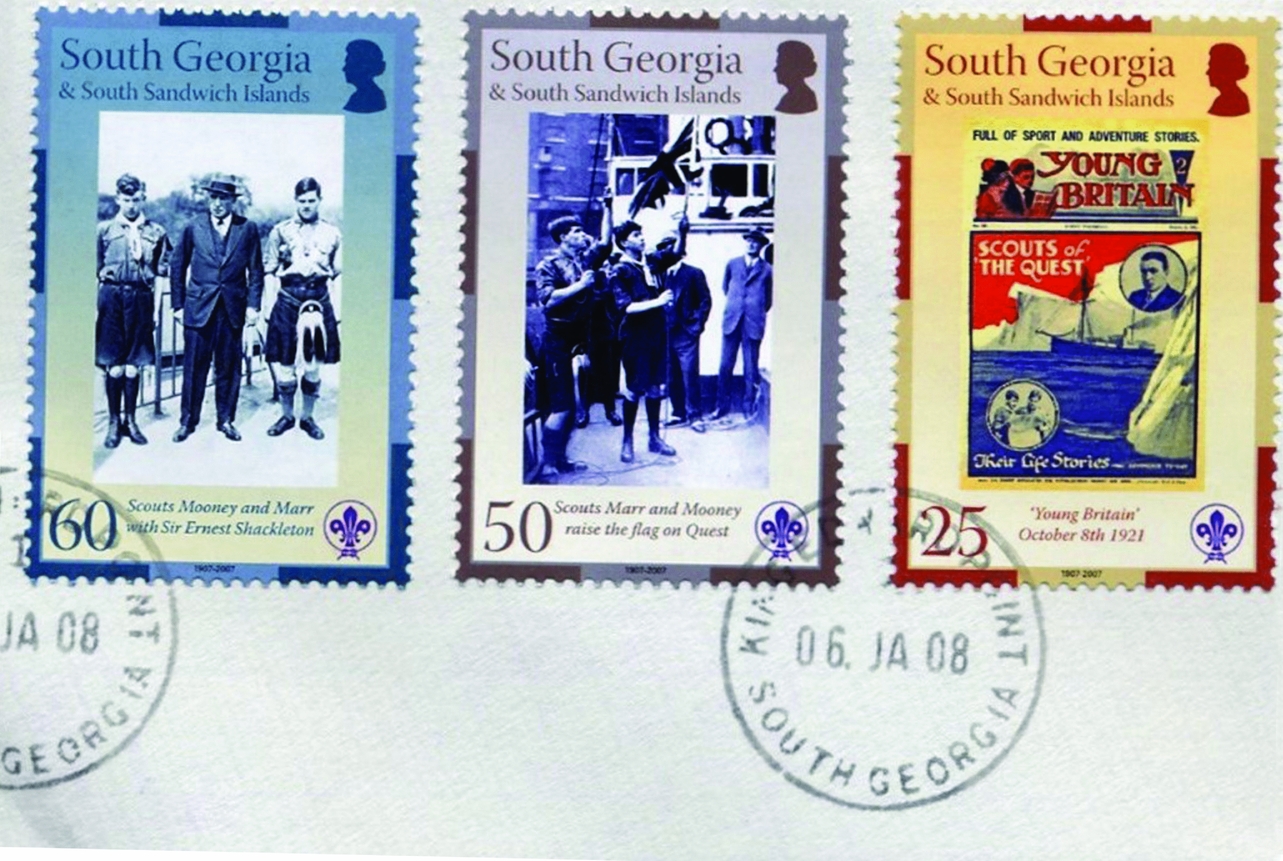

And what became of Norman Erlend Mooney? After returning to Kirkwall, where he was born (6 March 1905), he enrolled as a student engineer at the Royal College of Science and Technology in Glasgow. After graduating, he secured a position as land surveyor with the Ordnance Survey, based in Southampton. He married Lillias Keith in 1932 and they had two sons and a daughter. Erlend spent the latter years of his short life working for the Colonial Office in Nigeria. He was tragically killed on 20 November 1945 at the age of 40, in a rock fall at Jos in the centre of the country, where he is buried. On 6 January 2008, to commemorate the centenary of Sir Robert Baden-Powell's founding of the Boy Scout Movement, the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands issued five postage stamps featuring the Scouts of the Quest Expedition (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Postage stamps featuring the Boy Scouts of the Quest Expedition.

Acknowledgements

I dedicate this paper to Alec Mooney of Alloway, Ayrshire, who allowed me to examine and quote from his personal archive of photographs, articles and correspondence relating to his father, and for approving the text. I am also grateful to the reviewer who suggested substantial improvements to the text.