All members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict are combatants, except medical and religious personnel.

Customary Law – Rule 3; International Committee of the Red Cross

We are in a battle, and more than half of this battle is taking place in the battlefield of the media. We are in a media battle for the hearts and minds of our umma (community of Muslims).

Ayman al-Zawahiri, ‘Letter to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’, 2005.

Introduction

On 20 February 2019, Fabien Clain, one of the two ‘French voices of the caliphate’, was reported dead after an airstrike destroyed his shelter in Al-Baghouz Fouqani, Syria.Footnote 1 Previously imprisoned in France in the late 2000s for his role as an organiser in the Artigat jihadist cell, Fabien Clain became famous for the recording he made with his brother Jean-Michel, officially claiming the November 2015 attacks on behalf of the Islamic State. The brothers, also former Catholic hip hop artists, did not perpetrate attacks for the Islamic State.Footnote 2 Rather, Jean-Michel and Fabien Clain mostly engaged in jihad al-iliktruni, especially the release of propaganda advocating for jihad and the establishment of a caliphate. They shared anasheed (Islamic chants), audios calling Muslims to raise arms against the French government, and videos. For their incitement to terrorism, the two brothers could have faced 7 years in French prison and a fine of 100,000 euros,Footnote 3 in addition to another 10-year sentence for belonging to the group. However, Fabien and Jean-Michel Clain were killed on 20 February 2019 in an airstrike and on 5 May 2019 in a drone attack, respectively. In April 2019, the Islamic State’s leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi released a video paying tribute to his brother mujahid (combatant), Fabien Clain, thanking him for his contribution to jihad.Footnote 4

While there are legal ramifications to this case,Footnote 5 this paper focuses on the ethical tensions arising from these operations. The just war tradition places the distinction criterion at the core of the just conduct of war. Ethical belligerents, if they want to conduct a just war, are expected to discriminate between participants whose status render them ethically legitimate to harm and those, oppositionally, whose status based on moral innocence ought to offer them protection from direct and intentional harm.Footnote 6 Therefore, rather than operationally asking whether propagandists are treated as combatants on the ground, and rather than investigating how these participants appear in legal texts,Footnote 7 this article focuses on whether propagandists, via their activities, ought to be held ethically accountable in warfare, thereby making them ethically legitimate targets on the battlefield. The active role of propagandists puts into question the jus in bello criterion of distinction by blurring our perception of ‘who fights’.Footnote 8 It raises questions about the ethics of targeting them during war operations and introduces a question concerning the legitimate degree of harm these actors may face.

This article proceeds from the question: do propagandists take an active part in combat, such that they should ethically fall into the category of ‘combatants’, and are there limits to the associated degree of harm that these participants may face in conflict? Are propagandists relatively innocent, similar to civilians, or are the effects of their words in the conflict enough to classify them as combatants, whose deaths would be more ethically acceptable? Was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi right in calling Fabien Clain a mujahid? Are propagandists, such as the Clain brothers, ‘fighting’ to a degree that they should lose non-combatant immunity?

To answer the questions ‘are propagandists combatants?’ and ‘to what degree of harm could they be ethically subjected?’, this article proceeds in four steps. The first section reviews the importance of propaganda and propagandists in conflict, setting up the central problem concerning the uncertainty over their classification as combatants or non-combatants. The second section then provides an overview of the just war tradition’s binary frameworks for distinction, showing their uncertainty in assessing the ethical status of propagandists on the battlefield. In the third section, I build on two revisionist notions – liability to harm and participatory liability – to argue that propagandists should be morally considered as civilians non-liable to lethal harm., i.e. participants who should not be directly and intentionally killed in conflicts. In so doing, this article designates propagandists as indirectly participating civilians, whose activities render liable to only less-than-lethal harm. In the fourth section, I structure less-than-lethal harm in three categories of harm. To decide which category of harm may apply to specific situations, I introduce four new criteria, complementing the just war tradition criterion of necessity and its reinvention by Seth Lazar,Footnote 9 upon which belligerents could evaluate the degree of harm that propagandists ethically face. In doing so, this article contributes to the just war tradition by offering a clarification about the ethical status of a type of participant in conflict, that of the civilian propagandist. In providing a framework accounting for the diversity of propagandists – ancient, contemporary, legitimate, illegitimate, state, non-state – it not only reorients the debate onto a potentially new category of combatants but also offers new tools to ethically locate diverse individuals within new categories of distinction.

Communication, propaganda, warfare

Communication holds an essential role in the generation and conduct of conflicts. In fact, war is so embedded in stories that, Hidemi Suganami argues, ‘war origins are necessarily narratives, and as narratives they are artefacts constructed retrospectively for the sake of communicating arguments and ideas’.Footnote 10 Communication, narratives, stories constitute origins of wars. They make conflicts understandable within the larger flow of history and imbue them with meaning, often of a political nature. It is also through narratives that certain contemporary disqualified practices in warfare, such as torture, can come to be (re)accepted by military personnel and societies alike.Footnote 11

Communication acts are tools also used in the conduct of war itself. Belligerents increasingly rely on media manipulation and strategic communications to gain advantages in combat. Internally, communication revolves around the combat itself, in the sharing of tactical orientations and orders. Beyond the tactical level, belligerents also communicate to legitimise their actions, raise the morale of their troops, or mobilise new fighters. Externally, communication – visual,Footnote 12 spoken, written – permits organisations to disrupt the opponent using a wide range of discursive weapons, such as lies, threats, or claims of moral superiority.

Communication broadly refers to the act of sharing a message from a sender to a receiver. Ancient theories of communication included four components: the speaker, the speech act, the audience, and the purpose.Footnote 13 The latter dimension – the purpose – has received intense scrutiny. John Austin, for example, distinguishes forms of languages based on their purpose. While certain instances of communication hold a mere ‘descriptive’ dimension, others are performativeFootnote 14 because they intend to ‘do something’ by the mere act of ‘speaking’. Some communications, finally, are strategic in that they hope to contribute to desired outcomes.Footnote 15

Propaganda typically appears as an example of communication with a ‘strategic’ purpose. The term, when it was first used by the Roman Catholic Church, was initially cloaked with positive purpose: the wilful diffusion of ideas about the faith. For the Catholic Church, propaganda was perceived as ethical and necessary, as set out in the Vatican’s Congregatio de Propaganda Fide of 1622.Footnote 16 Contemporary understandings of propaganda, however, became infused with more negative connotations: it involves a speaker’s attempt to persuade an audience in order to obtain specific – usually political and strategic – results. For Edgar Henderson, ‘propaganda is a process which deliberately attempts through persuasion-techniques to secure from the propagandee before he can deliberate freely, the responses desired by the propagandists’.Footnote 17 Overly simplistic, propaganda is said to depict ‘a world in which the good guys and the bad guys are readily identifiable’.Footnote 18 Favouring subjective, passionate accounts over objective, impartial accounts of facts,Footnote 19 propagandists seek to gain the ‘influence of one person upon other persons when scientific knowledge and survival values are uncertain’.Footnote 20 Propaganda, therefore, for the purposes of this article, refers to ‘the intentional and strategic use of visual (e.g. gestures, pictures or written word) or aural (e.g. spoken words) communication to influence the opinions and behaviour of a target audience in an effort to achieve politico-military ends during times of conflict’.Footnote 21 In this article, I adopt this broad definition of propaganda to include any messaging that deliberately intends to generate strategic effects – in this case, in the context of a conflict – either behavioural or cognitive. Propagandists, by extension, are the people in charge of producing and promoting such strategic messaging to advance the interests of one party in a conflict.

Because propaganda helps to achieve strategic outcomes, warmakers have considered how to use propaganda effectively for as long as war has existed.Footnote 22 Alexander the Great, for example, developed multidimensional strategic communications supporting the extension of his empire with stories intimidating his enemies, framing his image as that of a god (in stories, images, on buildings and coins), and making sure that cities would be afforded his name (Alexandria).Footnote 23 In recent years, propaganda’s increased visibility enabled by information and communication technologies has allowed belligerents to more easily voice their cause, share grievances, mourn victims, or threaten enemies everywhere, making their visibility and influence more important, beyond the battlefield.Footnote 24 Because of the increased significance of communication on the battlefield, war studies scholars sought to move beyond the central, but maybe too restrictive, analyses of propaganda purposes.Footnote 25 Therefore, analyses focused on the speech act itself, in its contentFootnote 26 and format,Footnote 27 and on the audience receiving the communication.Footnote 28 Yet, surprisingly, the first component of any definition of communication, what Aristotle calls the ‘speaker’, received comparatively little attention, let alone in relation to its ethical responsibility on the battlefield.

This article chooses to focus on the ‘speaker’ dimension of propaganda, i.e. on the propagandists. While they are important participants for state and non-state military apparatuses, propagandists do not carry actual weapons, nor do they directly harm opponents with bullets. This has conceptually kept them from being seen as combatants, and thus legitimate targets for punishment. Some practitioners and scholars, however, argue that such participants should be directly targeted and eliminated.Footnote 29 What is the ethical status of those individuals whose propaganda production plays a role in combat? Are words an effective sword? Are propagandists combatants, and could they be legitimately harmed?

Distinction: The binary nature of combatants

The principle of distinction constitutes the core of jus in bello criteria.Footnote 30 According to the principle, belligerents have an ethical duty to distinguish between legitimate targets and those who ought to be protected from harm. The just war tradition usually refers to a dichotomic distinction composed of two exclusive categories: individuals are either combatants or non-combatants; they are either guilty or innocent.Footnote 31 Propagandists, however, might be convincingly analysed as having attributes of both categories.

Propagandists within the traditional combatant/non-combatant dichotomy

In his seminal work Just and Unjust Wars,Footnote 32 Michael Walzer proposes a framework, close to international law,Footnote 33 where soldiers lose their right to life because of the threat that their professional activity poses to others.Footnote 34 This is based on a decision-making process where we do not consider the individuals themselves in the decision over whether to legitimately target them, nor their ethical responsibility in the conflict, but rather their threatening role.Footnote 35 Individuals may be targeted on the basis of their activity – visible markers of combatancy such as a uniform or bearing arms – or because they pose an imminent, visible threat to someone’s survival, for example if they point weapons towards them.

Some propagandists are part of the military.Footnote 36 In this framework, propagandists belonging to a military apparatus are considered legitimate targets based on their affiliation with a threatening combating entity.Footnote 37 But some propagandists, if not most, will seek to favour one side without a clear affiliation to a military apparatus.Footnote 38 Uncertainty and disguise about the propagandist’s identity is indeed a critical part of most propaganda strategies. In white propaganda, the producer of the material is clearly identified. There is a complete openness about the identity of the organisation producing the material, for example the Dabiq magazines created by the Islamic State, or the messages of Voice of America. In opposition, black propaganda seemingly emanates from one source – e.g. Ukrainian civilians in Crimea – while actually being fabricated by another – e.g. the Kremlin.Footnote 39 Also known as ‘disinformation’, this type of propaganda uses deliberate false information by concealing who the actual propagandist is, whether military or not. This is, for example, the case of Buro Concordia, an apparently ‘freedom’, dissident, civilian-led radio from Britain, actually led by the Concordia Offices of Nazi Germany in Berlin, where ‘the propagandist could say whatever he pleases; he could lie, dissemble, attempt to mislead, cause confusion, spread rumours, create panic, or issue false orders’.Footnote 40 In grey propaganda, finally, the source of the material – the propagandist – is unknown or unclear. This is, for example, the case of some pro-Russian videos whose attribution is unclear, or of pro-Islamic State foundations whose clear belonging to the organisation is not verified.Footnote 41 Propaganda plays on identity and on the fog of information so that determining its source proves challenging. Consequently, any military affiliation of the propagandist, even if it exists, will either be hidden or unreliable (how can I be sure that the explicit source of the propaganda is actually military or civilian?). For this reason, I posit propagandists, by default, as civilian propagandists, given the frequent uncertainty of their status. Can the threatening role of even civilian propagandists make them subject to attack?

In Walzer’s traditional framework, because propagandists will not overtly assume their military status and do not pose an existential threat, they should be classified as non-combatants and should not be intentionally and directly targeted. This is in line with some interpretations of international law that consider how ‘civilians who support the armed forces (or armed groups) “by supplying labour, transporting supplies, serving as messengers or disseminating propaganda may not be subject to direct individualized attack”’.Footnote 42

Some scholars and practitioners, however, have denounced the insufficiency of this traditional Walzerian framework when highlighting the danger created by propagandists such as Anwar al-Awlaki, a prominent US-Yemeni propagandist within the Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula organization. With his propaganda, indeed, Al-Awlaki has been shown to have inspired dozens of terrorist attacks, including the 2009 Fort Hood attack, the suicide bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, as well as Faisal Shahzad’s attempt to bomb New York’s Times Square. Consequently, when building a threat assessment of propaganda activities, practitioners and strategists have argued for the strategic urgency to counter propagandists’ action on various battlefields, including by targeted eliminations and lethal harm against propagandists,Footnote 43 thereby revisiting the principle of distinction. But is there a via media, and is it possible to create a principle of distinction better accounting for the role and responsibility of civilian propagandists in war, so as to protect civilians, while giving opportunities for people on the ground to counter propagandistic activities?

The revisionist innocent/non-innocent dichotomy

To answer this question, I now wish to examine Jeff McMahan’s work, which challenges Walzer’s distinction principle and its grounding in affiliation. For revisionists, it is not so much their threatening role nor their affiliation with a military apparatus that makes individuals subject to attack. Rather, individuals can be targeted for a condition he calls ‘liable to harm’, if they hold a direct responsibility in the unjust threat that led to war.Footnote 44 For McMahan, ‘if a person is implicated in the existence of the problem in such a way that harming him in a certain way in the course of solving the problem would not wrong him, then he is liable to harm’.Footnote 45 Those who deserve protection are ethically innocent, meaning that they did not have a role in generating the unjust war.Footnote 46 Etymologically indeed, the innocent is one who plays no role in a nocent (the Latin word for harmful) endeavour.Footnote 47 In making this move, McMahan ties jus ad bellum and jus in bello together: the assessment of one’s responsibility in the emergence of war has a direct consequence for the assessment of how to conduct war ethically.

This responsibility-based conception has raised controversy given that some civilians who would be deemed non-combatants under Walzer’s framework can now be legitimately attacked. For McMahan, ‘there are certain non-combatants who bear a high degree of responsibility for a wrong that constitutes a just cause for war, if attacking them would make a substantial contribution to the achievement of the just cause, and if they can be attacked without disproportionate harm to those who are genuinely innocent, it may then be permissible to attack them’.Footnote 48 Historical examples can help explain the willingness to identify forms of liability for non-innocent civilians otherwise excluded by Walzer. In the 1994 Rwandan genocide, it is well-known that genocidaires used census and travel data supplied by the government to locate victims, showing a clear civilian contribution in the perpetuation of the genocide.Footnote 49 In that case, arguably, legitimate targets might include individuals such as town mayors or prefects who helped coordinate the massacre. During the Second World War too, the Nazi occupiers heavily relied on French civil servants to assist them in repression and genocide.Footnote 50 Following Hannah Arendt, who underlined the bureaucratic banality of Nazi Evil,Footnote 51 Mark Mazower notes that ‘bureaucrats served as instruments of repression, notably in round-ups of Jews and political opponents’.Footnote 52 Without civilian support, ‘targeted mass deportations were virtually impossible to achieve’.Footnote 53 In some circumstances, thus, civilians play a detrimental role in fomenting violence, even if they do not carry weapons. They are implicated, says McMahan, in the existence of the problem.

Revisionists, therefore, recognise that civilians might play a more or less detrimental role in conflict – by taking up arms, paying taxes, providing food or guns, voting, propagandising. Consequently, revisionists envision liability to harm as a continuum,Footnote 54 where one’s liability to harm depends on the extent of one’s implication in the generation and conduct of the conflict. For Christopher Finlay:

A variety of factors might … diminish the weight that official designations of combatant and noncombatant should be given in deliberating about how to fight … The alternative principle of discrimination would specify categories of enemy citizen – some combatants, some not – that are liable to attack. They would be identified on the basis of belonging to professions, for instance, or government departments that contribute to the wrongful violence that just war seeks to defeat.Footnote 55

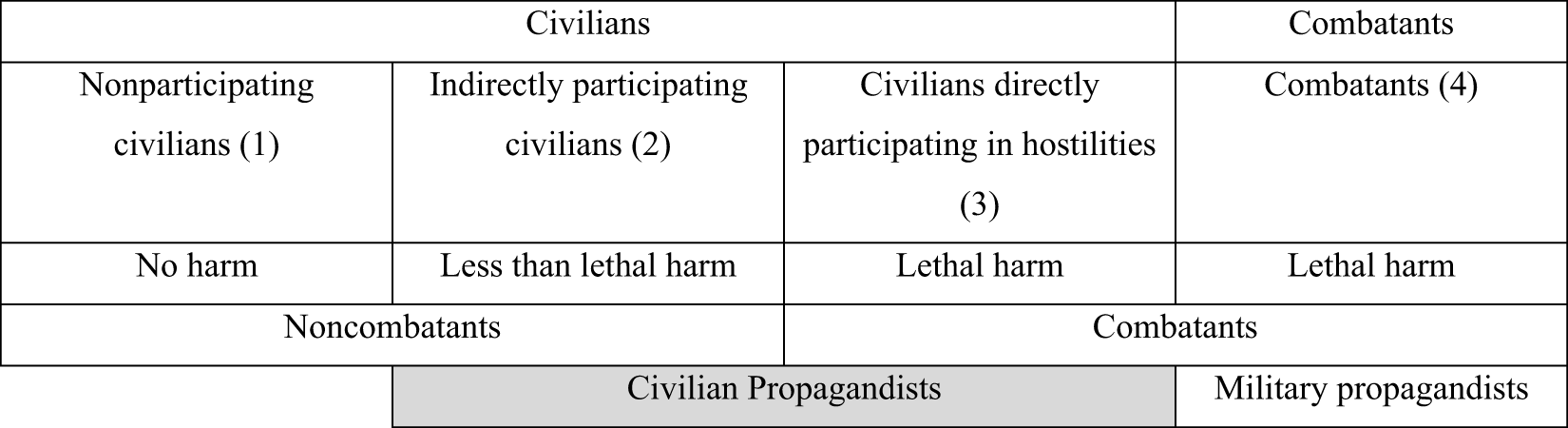

Building on this literature, Michael Gross advanced the notion of participatory liability for war participants, with the goal of applying McMahan’s liability to harm on the ground.Footnote 56 Like McMahan, Gross argues that liability to harm does not depend on affiliation but on the actions that agents directly take, considering that the greater a person’s participation in war activities, the greater harm an enemy may inflict, when it is necessary, to disable this participant.Footnote 57 Gross notes that each aspect of participation must be observable and objectifiable to be included in the calculation of liability: a person’s occupation, the service he provides, but not his supposed intentions. In my understanding, Gross’ conceptualisation generates a framework where four categories emerge (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Categories of ‘participatory liability’.

At one end of the scale are (1) non-combatants – or non-participating civilians – who assume no role in war-related activity. They are not responsible for any threat, are not part of military apparatuses, and, therefore, may suffer no direct intentional harm. In McMahan’s terms, they are innocent because they are not implicated in the existence of the problem to be solved. At the other end are (4) fully fledged combatants who conduct armed campaigns against enemy forces. Combatants belong to a military apparatus and are the main actor conducting hostilities. Without them, there can arguably be no conflict.Footnote 58 Due to their status and activities, combatants are liable to lethal (but not inhumane) harm when it is necessary to disable their person and disrupt their activities.Footnote 59

In the middle ground are participating civilians, e.g. civilians working for a guerrilla organisation’s political wing, for a state bureaucracy, or for the defence industry. These categories comprise those who help the conflict without clearly belonging to a military organisation. Because their implications vary, there are two types of intermediate participants: direct (3) or indirect (2). Article 51(3) of Additional Protocol I defines direct participation as: ‘acts which by their nature and purpose are intended to cause actual harm to the personnel and equipment of the armed forces’.Footnote 60 In Gross’s terms, this means that civilians directly participating in hostilities (3) undertake war-fighting activities. Because these civilians behave like combatants, bear arms, and attempt to provide a military advantage to their party, Gross contends that civilians undertaking war-fighting activities may, in this framework, be subjected to lethal harm.Footnote 61

Civilians who participate indirectly (2) undertake war-sustaining activities, ranging ‘from recruitment, training, and the provision of financial, media, and propaganda services to the design, production, shipment, and maintenance of weapons’.Footnote 62 Although their activities support one party to the conflict, such participants do not undertake any fighting nor any directly threatening activity that could nullify their civilian immunity. Indirectly participating civilians cannot be killed on purpose. However, such individuals contribute to the conflict and offer an advantage to their party; as such, they can be legitimately disabled. Indirectly participating civilians can suffer ‘less-than-lethal harm’, the degree of which needs to be evaluated (Figure 2).Footnote 63

Figure 2. Categories of participatory liability and associated harm.a

Both Gross and McMahan, therefore, associate liability to harm with one’s actions during conflict.Footnote 64 Where do propagandists fall in the framework?

Should propagandists be liable to harm? The revisionist uncertainty surrounding propagandists

Is propagandising a conflict participation that may warrant a liability to lethal harm? Some will say that this is so: propagandists, through their influence and voice, greatly contribute to the dynamics and results of the conflict, just or unjust, by mobilising fighters, inciting action, and threatening opponents. McMahan himself uses the example of the propagandist when he disqualifies Walzer’s approach, presenting propagandists as a notorious example of a ‘civilian population who is clearly a noncombatant but who bears significant moral responsibility for the wrong the redress of which constitutes the just cause for war’.Footnote 65 Propaganda indeed influences the very existence of conflicts. For example, scholars argued that, during the First World War, Lord Northcliffe’s PSYOPS messages designed at Wellington House drastically shortened the war’s duration.Footnote 66 According to a 1918 Times article, ‘good propaganda probably saved a year of war, and this meant the saving of thousands of millions of money and probably at least a million lives’.Footnote 67 Commander Hindenburg acknowledged in 1918 that ‘besides bombs which kill the body, his airmen throw down leaflets which are intended to kill the soul’,Footnote 68 leading George Bruntz to directly claim propaganda as a weapon.Footnote 69 Propaganda is thought to have greatly and directly participated in the elimination of an ‘unjust threat’ by helping the Allies in their fight against Germany.Footnote 70

Because propaganda contributes to eliminating unjust threats, it can conversely, when used by unjust belligerents, directly contribute to ‘unjust threats’. Adolf Hitler famously highlighted the importance of propaganda in winning conflicts, stating that ‘I was tormented by the thought that if Providence had put the conduct of German propaganda [during the First World War] into my hands, instead of into the hands of those incompetent and even criminal ignoramuses … the outcome of the struggle might have been different’.Footnote 71 Al-Zawahiri similarly recognised that half of Al-Qaeda’s battle occurs in the media realm.Footnote 72 Recently, the Kremlin’s propaganda apparatus greatly participated in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 73 Following McMahan therefore, propagandists, because of the significant impact of their messaging on the concretisation of the threat, may thus arguably be deemed ethically guilty if the threat is proven unjust. Would this make these participants liable to lethal harm in warfare?

Even if they are implicated, can propagandists be responsible enough so that they lose their immunity to harm? Several of McMahan’s students argue, oppositely, that propagandists, although responsible to some extent, probably fall short of meeting the thresholds of liability to lethal harm. Cécile Fabre, for example, contends that civilians, even if they participate in the war effort – by providing guns – do not meet the threshold of liability to lethal harm.Footnote 74 Therefore, even if they build the very weapons that make the war possible, civilians are not responsible enough for the unjust threat so as to make them liable to lethal harm. Propagandists, following this logic, might thus be even less liable to harm than civilian gun makers. David Rodin similarly argues that, even when perfectly executed, influence and propaganda activities cannot alone remove civilian immunity. Focusing on the 1954 Guatemala coup attempt and the United Fruit Company’s influence operations, Rodin concludes that ‘although this exercise of influence was wrong (granting McMahan’s interpretation), it falls short of meeting the burden required to become liable to lethal defensive force’.Footnote 75 Influencers are believed to be non-liable to lethal harm and should not be directly and intentionally targeted because they do not participate enough.

In line with this general uncertainty over the status of propagandists found in the literature, The Ethics of Insurgency contains an interesting tension: propagandists are mentioned as both direct and indirect participants (Figure 3). They are directly participating civilians liable to lethal harm when Gross notes that ‘with the exception of participating civilians who take up arms, lead military operations, or propagandize in favour of terrorism or genocide, most others are only liable to less-than-lethal harm’.Footnote 76 If propagandists advocate for grave crimes, they become subject to lethal harm. On the same page, however, Gross follows the ICRC Guidelines and defines indirect participation as including ‘financial and economic services, recruitment … propagandising and diplomacy, assembly and storage of IEDs; and “scientific research and design of weapons and equipment”’.Footnote 77 Civilian propagandists, in Gross, are both civilians directly participating in hostilities (3) and indirectly participating civilians (2). The distinction is important and has direct implications: in the first case, civilian propagandists would be subject to lethal harm; in the second, only less-than-lethal harm could be subjected.

Figure 3. Locating the propagandists within the categories of participatory liability in Gross’s framework.

I argue that framing propagandists as both directly and indirectly participating civilians, distinguishable by their messaging only, brings confusion. Is a propagandist with no influence nor reach but who advocated for terrorism more liable than a propagandist who engaged for years in manipulation for an autocracy or a non-state guerrilla that has committed war crimes, but has not advocated for terrorism?

Instead, I want to argue that propagandists, if they only engaged in propaganda activities,Footnote 78 may maximally be treated as indirectly participating civilians, liable only to less-than-lethal harm. This decision is underpinned by the maxim that if there is a doubt about the regime applicable to an individual (e.g. combatant or civilian), the most protective framework should be chosen.Footnote 79 It also builds on Cécile Fabre’s critique of the functionalist view, which argues that civilians rarely meet any threshold that would cause them to lose their immunity to lethal harm.Footnote 80 Civilians, even if they participate in activities related to the conflict, should not lose their immunity to lethal harm. Propagandists, therefore, are civilians who may not be killed intentionally for their actions in conflict.

However, propaganda plays a significant role, and moral belligerents may request ways of disrupting such activities. This article argues that a moral response to propagandistic activities may be found in less-than-lethal harm: a wide range of means, more or less disabling – but none of them lethal – which can be selected based on the propagandist’s ethical responsibility in the conflict.Footnote 81 Following Cian O’Driscoll’s concern with relinking just war tradition with ‘lived’ warfare on the ground,Footnote 82 I propose to build five criteria upon which one may assess the type of less-than-lethal harm that they propagandists might face. One criterion – military necessity – which I frame as ‘necessary criterion’, is taken from the just war jus in bello principles and its reinterpretation by Seth Lazar.Footnote 83 It aims to evaluate if less-than-lethal harm is warranted against a propagandist in a situation. Four additional criteria, which I call ‘assessment criteria’, are then designed based on the ethical specificities of propaganda. They aim at evaluating what type of less-than-lethal harm is warranted against that propagandist, depending on their activities.

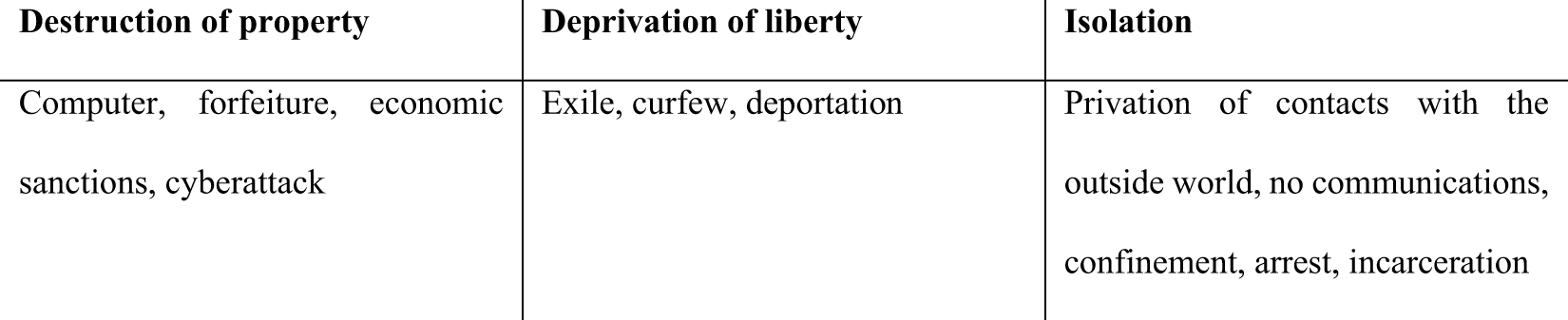

Establishing new criteria to assess propagandists’ liability to harm

Given the diversity of propagandists’ roles and responsibilities on the battlefield, there is a need to determine if and which sort of less-than-lethal harm they can face. Belligerents have access to a wide range of harm in conflicts. What Elisabeth Wood calls a repertoire of violence includes ‘a set of practices that a group routinely engages in as it makes claims on other political or social actors’.Footnote 84 While lethal means refer to weapons able to kill a target, less-than-lethal means refer to the ability to disable while avoiding severe, long-term injury or irreversible psychological harm; they include cyberattack, economic sanctions, restrictions on liberty, e.g. arrest, curfew, or deportation.Footnote 85 An authority mostly granted to police officers and security forces, less-than-lethal force means to ‘ensure that the minimum amount of force is applied in a given situation’.Footnote 86

For clarity purposes, I identify, in this article, three categories of less-than-lethal measures that I rank along a continuum of harm (from less to more harmful) (Figure 4). These categories offer a structured overview of the means with which belligerents may disable propagandistic activities without using lethal force: from the simple destruction of property (computers, economic sanctions) to the isolation of the propagandist.

Figure 4. Gradation of less-than-lethal harm.

Less-than-lethal measures on the right of this structured continuum generate more harm to the propagandist than those on the left. The key is to find a way to assess which of these more or less ‘harmful’ categories are morally, and maximally, applicable to propagandists, based on each context.

I identify five criteria. One of these criteria, military necessity, is taken from the just war tradition and will be acting as the ‘necessary criterion’. This means that it is hierarchically prevalent and that it will apply before any type of harm may be induced to propagandists (and any participants to the conflict). No harm can be done to propagandists which does not meet the condition of necessity.Footnote 87 This criterion determines whether a less-than-lethal measure may be applied to a propagandist. It is decisive.

I then propose the establishment of four new criteria – which I call ‘assessment criteria’ – designed to decide the degree of harm that propagandists may face. Assessment criteria evaluate which category of less-than-lethal harm (destruction of property, deprivation of liberty, isolation) may apply to a specific propagandist. These criteria are cumulative and non-necessary: the more a propagandist meets the four assessment criteria taken together, the more they may be exposed to less-than-lethal harm on the right end of the continuum.

To establish these new criteria, one should wonder: what makes propaganda particularly problematic at the ethical level?Footnote 88 From there, can we differentiate several propagandistic behaviours so as to ascribe the degree of harm to the corresponding propaganda activity? Are there elements that make some propagandists ‘worse' than others, thereby helping us consider the type of harm – in agreement with moral obligations relating to the prohibition of inflicting unnecessary suffering, and to requirements of proportionality – that propagandists may face on the battlefield?

Necessary criterion (NC): Military necessity

The first criterion when deciding if and what harm should be done to propagandists is military necessity, a central criterion of the just war tradition’s jus in bello. Military necessary here acts as the prevalent criterion, i.e. as one, and the only, necessary condition. It decides whether any type of less-than-lethal harm should be applied to a specific propagandist (while assessment criteria will rather focus on which type of less-than-lethal harm could be applied). Military necessity considers that ‘in situations where the only way to achieve military victory in a Just War requires the employment of a certain tactic, say the bombing of cities, then that tactic is justified regardless of other normative considerations’.Footnote 89 In other words, military necessity ‘permits only that degree and kind of force required to achieve the legitimate purpose of a conflict’.Footnote 90

Targeting propagandists: A military necessity?

Can harming civilian propagandists non-lethally be sometimes justifiable following military necessity? According to the principle, a justified tactic must aim to help the military defeat of the enemy, focusing on a military objective and goal.Footnote 91 Is propaganda a military objective, and can the destruction of its producer provide a decisive military advantage? Propagandists do not usually act directly at the level of tactical, directly military communications, so that attacking them would significantly weaken the opponent militarily. Rather, propagandists contribute to strengthening the military more indirectly by recruiting fighters or providing technical guidelines.Footnote 92 This has led Amnesty International to conclude, in its 2000 report about the NATO bombings in Yugoslavia, that targeting propagandists may never be a military necessity offering a decisive military advantage:

Disrupting government propaganda may help to undermine the morale of the population and the armed forces, but … justifying an attack on a civilian facility on such grounds stretches the meaning of ‘effective contribution to military action’ and ‘definite military advantage’ beyond the acceptable bounds of interpretation.Footnote 93

The military nature of necessity might arguably make this criterion too restrictive to offer reasonable chances of success to belligerents fighting against unconventional fighters and propaganda operations.

Reinventing military necessity

Recent conceptions of necessity within the just war tradition, therefore, have tried to incorporate new participants in war by detaching notions of necessity from solely military dimensions, which, I argue, could be an avenue applicable to the provision of less-than-lethal harm. Seth Lazar identifies three criteria of necessity upon which to operationalise the decision to target.Footnote 94 First, the harm done, he contends, must not be an end in itself, but rather a means towards achieving a goal, and the harm done must be shown to be somewhat effective at achieving that goal. Second, ‘there must be no less harmful course of action with equal or better prospects of achieving the goal’.Footnote 95 Third, ‘if there is a less harmful course of action available that is less likely to succeed, then the difference in prospects of success – or effectiveness – must be sufficiently weighty to justify the difference in harm inflicted’.Footnote 96 All three conditions, argues Lazar, are individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions designed to ensure that the harm done to a non-combatant is necessary.

Can harm done to a propagandist fulfil all three jointly sufficient conditions? Following condition 1, harming the non-combatant propagandist ought to be a means towards achieving a broader goal. Removing propagandists from the battlefield holds strategic advantages: weakening the opponent’s ideology, countering normative attacks against one’s cause, preventing the use of lies in future operations, reducing the probabilities of falling into the enemy’s trap or into believing rumours able to cause moral outrage. Harming a propagandist, Amnesty International’s report recognised, may well be a means towards achieving an end.

Conditions 2 and 3 prove harder to fulfil. One needs to prove that less-than-lethal action, for example privation of liberty or isolation, is significantly more likely to succeed than other non-harmful (or less harmful) courses of action to achieve the above-mentioned goals. It requires showing: (a) that simply targeting the propaganda systems (Option 1, ‘Destruction of property’ in our continuum) or countering its effects, rather than harming the propagandist (Option 2, ‘Privation of liberty’, or 3, ‘Isolation’) would not have brought similar results in neutralising the propaganda content and (b) that only targeting the propaganda infrastructures or content (non-harm or Option 1) rather than the propagandist (Options 2 and 3) would have exposed the belligerent to significant harm, justifying the provision of harm instead. Lazar’s conception of necessity shows that when it is impossible or inefficient to target the propaganda content or infrastructures (Option 1), it may become ethically sound to neutralise the propagandists themselves (Options 2 and 3).

NC: The less-than-lethal measure must be shown to be ‘necessary’. In other words, one must be able to demonstrate that exposing propagandists to this type of less-than-lethal harm is justifiable because (1) It is done towards a higher, preferably military, goal; (2) Harming the propagandists (rather than just the content or systems) brings significantly higher chances of success; (3) Harming the propagandists (rather than just the content or systems) brings significantly less danger and direct harm to the belligerent. The three conditions together set the justifiability and degree of less-than-lethal harm that is indeed ‘necessary’ against the threat represented by the propagandist.

While military necessity should probably prevail when assessing the provision of ‘lethal harm’ to a participant, Seth Lazar’s reinvention of necessity, I argue, proves helpful to determine if a propagandist can be subjected to ‘less-than-lethal harm’. Propaganda, however, differs from more traditional war-sustaining activities, and here I want to propose some ‘assessment criteria’ to evaluate what degree of harm they can be subjected to, if warranted. What criteria should be considered when assessing the degree of harm? I propose the establishment of four new criteria specific to propagandists – which will need to be further explored outside of this article – but which could potentially help assess the degree of harm that propagandists may legitimately face.

Assessment criterion (AC) 1: Denial of agency

A first specificity linked to propaganda activities lies in the fact that it aims to ‘trick’ people into doing or believing something.Footnote 97 Earlier in this article, Henderson was quoted saying that propaganda’s goal was ‘to secure from the propagandee before he can deliberate freely’.Footnote 98 Put differently, propaganda removes people’s ability to choose freely and instead imposes obstacles to a free exercise of their agency.Footnote 99 As recalled by Jacques Ellul, propaganda content seeks to manipulate people through the dispossession of the recipient.Footnote 100 The manipulation of the recipient leads to a condition where they are suddenly not themselves, nor do they have access to their usual capacities. Manipulation, in semiotics, refers to the attempt by the sender to incite the recipient into doing something. Insofar as its purpose is to incite people into doing something, propaganda holds a manipulative element that effectively weakens the recipient’s ability to act rationally by themselves.Footnote 101

The just war tradition has long included notions of manipulation and agency within its frameworks. As an example, the issuance of warnings before targeting a population is broadly conceived as ethical because it gives the population a choice to desert the target, a decision to make, that is, some agency.Footnote 102 Knowing the situation, individuals may choose how to act. Propagandists do not offer this choice, as they expose populations to manipulative content without issuing warnings. Via their manipulation, propagandists not only deny the possibility of choice, but they also explicitly disorient their knowledge and alter the population’s ability to make conscious decisions, to act as rational human beings. In doing so, propagandists actively seek to destroy the very characteristic of the liberal human being: their agency and, following Jenkins’s conception, their identity.Footnote 103

Cases of black propaganda, which disorients the audience by providing disinformation about the origin, goal, and context of the material, and cases of grey propaganda, which remains unclear about who speaks and why, arguably hold more manipulative elements than white propaganda, where the locutor explicitly tells who they are and their positionality towards the cause. In white propaganda, even if there are some manipulative elements due to the proposed interpretation of facts, the audience can still exercise their agency – for example by choosing not to read or watch it – based on the locutor’s origin and reliability. Propagandists found ‘guilty’ of black or grey propaganda, because they deny the audience’s agency more, may be subject to more less-than-lethal harm than producers of white propaganda.

AC 1. Propagandists who actively use manipulation in order to reach their political and/or military objectives can be subject to more harm than those who do not.

Assessment criterion 2: Deliberate falsehood

Not only does propaganda manipulate, it also, on some occasions, explicitly lies. Are propagandists who lie subject to more harm than those who do not? Is the spread of false information and wrong facts an aggravating circumstance that plays against the propagandists in the assessment of their ethical responsibility? Can the deliberate falsehood which characterises certain forms of propaganda be used as an ethical basis for the propagandists’ liability to harm?

Some propaganda contents are manipulative (Assessment criterion 1) while relying on truthful and accurate, verifiable facts. Elie Tenenbaum explains that during the Second World War, ‘the British approach … was based on a truth policy. Although biased in their presentation of the facts, the information disseminated by the psychological warfare services is never contradicted by reality.’Footnote 104 Sir John Reith famously coined the British propaganda strategy during the Second World War as an approach built upon ‘the truth, nothing but the truth and, as near as possible, the whole truth’. Arguing that credibility is a key element of a propaganda battle, Britain chose to build its own messaging upon verifiable facts and ‘true’ elements. Frank Capra’s film Why We Fight similarly intended to ‘shape perceptions without telling lies’,Footnote 105 in other words, to manipulate without creating false information. This contrasts highly, explains Tenenbaum, with ‘Nazi or Soviet propaganda apparatuses, which relied solely on the mobilisation of the masses to the detriment of veracity or even credibility’.Footnote 106 In the latter cases, propaganda heavily relied on false, fabricated pieces and lies, building on secret and deceptive actions.Footnote 107 Between the two, a vast majority of propaganda contents includes appeals to known facts coupled with almost-truths, distortion, and oversimplification.Footnote 108 Propaganda, therefore, frequently conflates facts with inferences and values and lies to its recipient to achieve political and strategic goals.Footnote 109

Some propaganda content lies more than other. Truth, in that respect, is sometimes distorted and instrumentalised in propaganda. Is that an aggravating circumstance when it comes to propagandists’ ethical liability to harm? Truth has often been analysed as a victim of war. For Gross, lying is not illegitimate in war and ‘the truth is a legitimate casualty of just war’.Footnote 110 Several Muslim scholars also seemingly believe in the permissibility of lying in war,Footnote 111 while, for Augustine and his Christian followers, just fighters have ‘as an instrument of God or the just state … a duty to fight and lie’.Footnote 112 Lies may be permissible to help conduct a just war.

Other scholars, however, would say that deliberate falsehood and lies should absolutely be rejected and condemned for their immorality, even in wartime. In his search for the virtuous propagandist, therefore, Roger Herbert highlights how ‘a leader who lies and manipulates to mobilize his people for a just and necessary war is a liar and a manipulator, with all the moral blame that these vices warrant independently. His actions may be excused by the catastrophe he averts, but his hands are dirty. The tactics of a virtuous propagandist, by contrast, require no excuse.’Footnote 113 Additionally, says Stanley Cunningham, lies are perceived as ethically problematic because they reduce the virtue of truth to a simple instrument which can be used for other ends.Footnote 114 Rather than an end, truth is perceived in an instrumental fashion, seen as a means to achieve other goals.

How can we make sense of this uncertainty about the status of lies as an aggravating or accepted circumstance of war? I argue that a ‘legitimate’ and necessary lie – for example, to protect populations or troops – ought not to be included as an aggravating circumstance for the propagandist.Footnote 115 However, altered images, deep fake videos, and lies that intentionally conceal or transform the truth with the effect of harming may contribute to a harsher assessment of a propagandist’s responsibility in conflict, and therefore a harsher less-than-lethal harm treatment. The distinction between black, grey, and white propaganda may here again prove useful. Because it purposefully wrongs the audience about the origin of the messaging, black propaganda, unlike grey and white propaganda, lies. When its goal is not to protect populations, it therefore exposes its producer to more less-than-lethal harm than authors of grey and white forms of propaganda.

AC 2. False facts that deliberately deceive the recipient for a hostile purpose. This latter type of lies potentially expose the propagandist to additional harm on the battlefield.

Assessment criterion 3: Influence

A third way to assess which type of less-than-lethal harm a propagandist can legitimately face may be to focus on their impact. Should the legitimate degree of harm inflicted upon the propagandist grow based on the audience they were able to reach? Is it legitimate to harm a powerful, influential propagandist more than a rather isolated propagandist who would produce the same content? I want to suggest here that the bigger the influence and outreach that this propagandist has, the more they may be subject to less-than-lethal harm situated on the right end of our continuum.

When he analyses the key drivers of a good counter-propaganda strategy, communication specialist Haroro J. Ingram emphasises the need to ‘use various means of communication to maximise the message’s reach, timeliness and targeting’.Footnote 116 An efficient and impactful (counter)-propaganda therefore, is one that reaches people. Similarly, Terence Qualter, in 1962, highlighted that successful propaganda ‘must be seen, understood, remembered, and acted on’.Footnote 117 In both cases, the first criterion rendering a propaganda successful has to do with its ability to be seen by people. By extension, this arguably means that propaganda that reaches more people participates more in the conflict than limited propaganda. Using Gross, this means that a propagandist whose content only reaches their most immediate circle of already-convinced followers arguably participates less in the conflict and therefore holds a lesser responsibility – following McMahan’s formulation – than a propagandist such as Anwar al-Awlaki whose contents reached thousands of followers on four different continents.Footnote 118 Measuring the scope and influence of the propagandist’s voice helps assess the harm caused by such a participant in hostilities. All in all, influential voices may arguably be subject to graver harm within the less-than-lethal repertoire of harm than non-influential ones, because they arguably participate more in the conflict.

AC 3. A propagandist with higher influence and outreach might suffer more less-than-lethal harm than a propagandist with a limited scope or audience.

Assessment criterion 4: Gratification

Should paid propagandists be more punished than voluntary (as in unpaid) propagandists? Two opposing ethical views can be developed. On the first view, paid propagandists ought to suffer more harm than unpaid ones because of the professional connotation associated with their activity. Because they are paid, one can argue, the propagandists are part of a systemic attempt at manipulating, and they receive gratification for their deception.Footnote 119 If the propagandist is paid, I shall say, they are part of a deliberate industrial propaganda machine which cannot ignore its effects and intentions.

However, I can also develop the opposing ethical view. Paid propagandists, indeed, can act out of necessity. Following McMahan’s framework of ethical liability, a propagandist who manipulates because they need to feed their family holds less ethical responsibility and guilt than one who acts voluntarily, out of conviction for the defended cause.Footnote 120 Some propagandists may do so because they firmly and genuinely believe in a cause, because they ‘intend’ to persuade people, harm others, and help one side in the detriment of the other, without any financial gratification.Footnote 121

A way to solve this ethical dilemma might lie in the cumulative dimension of the assessment criteria proposed in my model. Arguably indeed, a paid propagandist may be part of a bigger machine, of a system with higher reach and influence, thereby leaning more onto the right end of the continuum, following Assessment criterion 2. Put simply, if a propagandist is paid, they are probably part of a structure that provides them with higher influence and outreach capacities than an isolated, unpaid propagandist. Whether being paid worsens or improves one’s ethical situation on the battlefield therefore remains to be decided, beyond the scope of this article.

AC 4. Gratification, however, may be associated with higher influence capabilities, and higher implication in the generation of the unjust threat, thereby leaning towards the right end of our continuum of harm.

More research should examine the ethical impact of professionalism on war participation (through voluntary, forced, or monetarily motivated conscription) and see how the ‘payment’ principle that I suggest here effectively plays into the ethical responsibility of propagandists on the battlefield.

Conclusion

This article questioned the ethical status of propagandists during armed conflicts. It argued that civilian propagandists ought to be primarily morally seen as indirectly participating civilians whose contribution to the war effort could not be ignored but is not significant – or at least not identifiable – enough to render them liable to lethal harm. Propagandists, it argues, should be seen as civilians not liable to lethal harm, meaning that they cannot be intentionally and directly targeted (lethally) for their activities. Instead, this article contends that, as indirectly participating civilians, propagandists may rather be, in some conditions, subjected to less-than-lethal harm. Among the wide repertoire of less-than-lethal harm practices available to belligerents in conflict situations – destruction of property, privation of liberty, isolation – one must decide on the type of harm, more or less harmful, more or less incapacitating, which is ethically, and maximally, legitimate. This requires an assessment of the propagandists’ responsibility, through just war criteria.

This article has argued that one might assess the degree of less-than-lethal harm that propagandists may legitimately face in conflict in two steps, by analysing:

• If a harm may be inflicted. Following the necessary criterion, a less-than-lethal-harm measure may be undertaken if one may show:

(1) The necessity of disabling them as a person, rather than only their content. Following the NC, one must be able to demonstrate that exposing propagandists to this type of less-than-lethal harm is justifiable because (a) it is done towards a higher, preferably military, goal; (b) harming the propagandists (rather than just the content or systems) brings significantly higher chances of success; (c) harming the propagandists (rather than just the content or systems) brings significantly less danger and direct harm to the belligerent. The three conditions together set whether less-than-lethal harm is ‘necessary’ against the type of threat represented by the propagandist.

• What harm may be inflicted. Following the assessment criteria designed to designate which type of less-than-lethal harm may be more appropriate along a continuum of measures:

(1) The degree of manipulation (AC 1). Propagandists who actively use manipulation in order to reach their political and/or military objectives should be subject to more harm than those who do not.

(2) Their relationship to the truth and its instrumentalisation (AC 2). False facts that deliberately deceive the recipient for a hostile cause are unethical. This type of lies potentially expose the propagandist to additional harm on the battlefield.

(3) Influence and outreach (AC 3). A propagandist with higher influence and outreach may suffer more less-than-lethal harm than a propagandist with a limited scope or audience.

(4) The level, if any, of gratification, received by the propagandists (AC4). Gratification may be associated with higher influence capabilities, and higher implication in the generation of the unjust threat, thereby leaning towards the right end of our continuum of harm.

The reader might be surprised not to see any account of intention in the proposed criteria. Intuitively indeed, a propagandist designing content to deceive might bear more responsibility for the unjust threat than someone unknowingly spreading or redesigning propaganda. As mentioned earlier, however, just war principles of distinction have long tried to focus on observable criteria – on verifiable measures, if not on the ground, then through intelligence work.

More research should undoubtedly examine the issue and, more specifically, the relevance of the five criteria put forward in the last section. Those criteria indeed are but an exploration of the potential ethical specificities of propagandists on the battlefield. Their only claim and goal is to act as potential heuristic tools designed to assess the degree of harm propagandists could be subjected to. Much work remains to be done however, to assess the relevance of these criteria in specific propaganda cases, to potentially explore new tools, and/or to strengthen the link between the different criteria and the effects of their potential aggregation. More research could also explore the link between these five criteria and Gross’s distinction between directly and indirectly participating civilians.

Video abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000044

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable and helpful feedback on this article, as well as the editorial team at the Review of International Studies who made this publication process both smooth and encouraging. I would also like to thank Vincent C. Keating, Amelie Theussen, Jean-Vincent Holeindre, Rory Cox, Kurt Klaudi Klausen, and Cian O’Driscoll, as well as my colleagues at the Center for War Studies (University of Southern Denmark) and Centre Thucydide (Université Paris-Panthéon Assas) for their comments on previous versions of this paper.