Introduction

The transition from work to retirement has been an issue of lively scientific discussion for many years, prompted, in part, by an interest in understanding recent transformations in the process. Previous concepts such as disengagement theory had emphasised retirement as an exit from roles and relationships and as a gradual withdrawal from society (Cumming and Henry Reference Cumming and Henry1961). This contrasts with activity theory, which suggests that individuals find new activities to replace work, and continuity theory which views the retirement transition period in terms of continuity of lifestyles and core values (Atchley Reference Atchley1989, Reference Atchley2000; Havighurst Reference Havighurst1961; Hooyman and Kiyak Reference Hooyman and Kiyak2000).

However, these generalised theories have been criticised as too crude and simplified to explain the retirement transition, with more recent analyses highlighting the importance of lifecourse perspectives which acknowledge the complex interactions between individual personalities, family circumstances, health and the multiple institutional contexts in which lives develop giving rise to considerable variation in the retirement process and subsequent outcomes (Calasanti Reference Calasanti1996; Nordenmark and Stattin Reference Nordenmark and Stattin2009). The evolution of these theoretical perspectives also reflects shifts in the circumstances of retirement, which have been undergoing significant change in Western societies as an increasingly individualised experience, with greater variety of timing and pattern.

Alongside an increased diversity of retirement pathways is a shift in perceptions and expectations of the retirement years, theorised as a new ‘cultural space’ and characterised by new ways of living (Gilleard and Higgs Reference Gilleard and Higgs2002; Hinterlong, Morrow-Howell and Sherraden Reference Hinterlong, Morrow-Howell, Sherraden, Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong and Sherraden2001; Hyde et al. Reference Hyde, Ferrie, Higgs, Mein and Nazroo2004). While retirement poses two key challenges of how to manage the threat of marginality and how to exploit the promise of new-found freedoms (Weiss Reference Weiss2005), with greater affluence and longer lives the retirement years are increasingly said to offer scope for expanded opportunities for a new, active and positive phase of life (Freedman Reference Freedman1999; Gee and Baillie Reference Gee and Baillie1999; Hewitt, Howie and Feldman Reference Hewitt, Howie and Feldman2010). The retirement transition is therefore increasingly seen as a critical point at which people can learn, by taking control of the process, to become ‘architects of their future’ (Gale Reference Gale2014: 126).

This is in line with the ‘active ageing’ paradigm which has developed in Europe especially in the last decade. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), active ageing is the process of optimising opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age (WHO 2002). Activity in older age is also central to the concepts of ‘successful ageing’ and ‘productive ageing’ which have developed mainly in the United States of America (USA). While these three terms are sometimes treated synonymously (Foster and Walker Reference Foster and Walker2015) and have in common a neoliberal emphasis on personal responsibility and signal the expectation that older people will continue to contribute to society rather than being a burden on health and welfare services (Neilson Reference Neilson2006; Pike Reference Pike2011), there are differences between them. Good health seems to be a precondition of ‘successful ageing’ (Foster and Walker Reference Foster and Walker2015), which seeks to minimise the risk of disease and disability and promote social engagement, physical activity and cognitive function (Rowe and Kahn Reference Rowe and Kahn1987, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997, Reference Rowe and Kahn2015), whereas the active ageing paradigm is more focused on health benefits and wellbeing as outcomes of activity. Productive ageing has a narrower focus on mobilising the productive potential of older people towards work, volunteering and education, to use the skills and experience of older people better both for individual and public good (Butler and Gleason Reference Butler and Gleason1985; Caro, Bass and Chen Reference Caro, Bass and Chen1993). The active ageing perspective, although still dominated by an economic focus (Hofäcker Reference Hofäcker2015; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2006), does include additional fields of activity not necessarily linked to the production of goods or services, including participation in the social, cultural, spiritual and civic spheres (Foster and Walker Reference Foster and Walker2015). Active ageing is a central principle of current European policy making (e.g. European Commission 2014), has influenced national policies of most member states (e.g. Department for Work and Pensions 2015), and is being monitored across Europe through the Active Ageing Index (AAI) policy tool which measures active and healthy ageing indicators (Zaidi et al. Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Hofmarcher, Lelkes, Marin, Rodrigues, Schmidt, Vanhuysse and Zolyomi2013; Zaidi and Stanton Reference Zaidi and Stanton2015).

Despite observations of an increased diversity of roles and activities among ‘retired’ people, it has been recognised that in older age the propensity and the ability to participate in this new cultural landscape and adopt the new roles which are opening up, varies by cultural groups (Ranzijn Reference Ranzijn2010), social position (Gilleard and Higgs Reference Gilleard and Higgs2002; Hyde et al. Reference Hyde, Ferrie, Higgs, Mein and Nazroo2004; Price Reference Price2002) and individual choice. In addition, ‘labour markets, welfare systems and pension systems jointly set the context in which individual retirement trajectories unfold’ (Fasang Reference Fasang2012: 689). Opportunities may also be more locally determined, according to the degree of local authority/federal funding patterns, and costs of access to public spaces and facilities (Deeming Reference Deeming2009).

In order to explore further the potential influence of opportunity structures for active ageing, both national and local, this paper examines experiences of older workers making the transition from work to retirement, comparing Italy, England and the USA. The paper reports findings from the baseline year of a three-year qualitative study while individuals were still in employment, to explore expectations and plans for retired life, and the range of opportunities foreseen. Our main interest in this paper is to understand to what extent pre-retiree plans are aligned with the active ageing concept; and how these plans may be shaped by social structure. We introduce the voices of individuals on the cusp of retirement to provide a more nuanced understanding of how far the active ageing agenda is consistent with their hopes, aspirations and perceived opportunities. This will highlight how social policies or interventions can be targeted to meet needs and facilitate life plans. In addition, the anticipation of retirement can be a troubling experience (Nuttman-Schwartz Reference Nuttman-Schwartz2004) and therefore understanding the anxieties and concerns at this stage can point to the type of support that might helpfully be offered to pre-retirees. It is important to examine individuals’ plans as they embark on the retirement process because underlying attitudes and beliefs potentially shape their early retirement lifestyles which, in turn, influence the overall trajectory of their retirement. This study builds on previous research both methodologically and in providing an international comparative dimension. Most qualitative research investigations on the retirement transition to date have focused on retirement adjustments by conducting interviews at one point in time after retirement, with appraisal of anticipations and the gap between expectations and outcomes based on retrospective recall, with attendant methodological limitations (Byles et al. Reference Byles, Tavener, Robinson, Parkinson, Smith, Stevenson, Leigh and Curryer2013; Nimrod, Janke and Kleiber Reference Nimrod, Janke and Kleiber2008; Price Reference Price2002; Price and Nesteruk Reference Price and Nesteruk2010; Robinson, Demetre and Corney Reference Robinson, Demetre and Corney2011). In some instances where individuals retired several years beforehand, memories may have faded thereby risking distortions in recollections of feelings and anxieties; and the past will be interpreted in light of subsequent experiences and events. Furthermore, among the few qualitative studies which have examined retirement expectations before retirement, the majority interviewed workers when they were quite far from reaching retirement (Jonsson, Kielhofner and Borell Reference Jonsson, Kielhofner and Borell1997; Weiss Reference Weiss2005; Winston and Barnes Reference Winston and Barnes2007), while in this study older workers were interviewed very close to their retirement when plans and thoughts about retirement were particularly sharp and concrete (Ekerdt, Kosloski and De Viney Reference Ekerdt, Kosloski and De Viney2000). Moreover, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to explore retirement plans in relation to the active ageing concept.

With qualitative interviews conducted in England, Italy and the USA, this paper provides a comparative perspective and aims to understand whether there is variation in active ageing-related plans for retirement, reflecting inter-country cultural differences in relation to both values and distinct welfare regimes which shape the opportunity structure confronting individuals at this stage of life. Insofar as public policies determine work opportunities, income, learning and training options, and family responsibility constraints (reflecting provision of services), individuals residing in countries with different institutional settings might exhibit distinct orientations towards retirement and different plans for how they will use their time. As also underlined by Walker and Maltby (Reference Walker and Maltby2012), there is the need to acknowledge and respect national and cultural diversity in relation to preferred forms of activity and social participation of older people.

The three countries under study reflect cultural diversity in terms of economic and welfare regime, including differences in the institutional setting which regulates the transition from work to retirement. Italy represents a Mediterranean welfare regime where the role of the family is central (Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996). A ‘familistic culture’ has been used to describe the strong family ties evident in southern Europe (Reher Reference Reher1998) and in a familistic society ‘personal utility and family utility are considered the same’ (Tomassini et al. Reference Tomassini, Glaser, Wolf, Broese van Groenou and Grundy2004: 27). Child-care and elder-care are predominantly delegated to the family. Formal care arrangements are less developed (Anttonen and Sipilä Reference Anttonen and Sipilä1996), which inhibits female participation in the labour market (Bettio and Plantenga Reference Bettio and Plantenga2004) and has implications for the range of options facing older people as they enter retirement, as retirees become a resource for caring roles. Concerning the transition from work to retirement, the Italian context is dominated by increased barriers to early retirement, with economic penalties associated with retirement before age 62. Anti-age discrimination legislation in employment was introduced in 2003, and recent labour market reforms prevent large companies firing workers who reach the statutory retirement age, in order to allow workers to remain employed until the age of 70. Despite these reforms, the effective average retirement age is lower than in most European countries. In Italy it is challenging to combine work with a pension, as an Italian employee must first exit employment to become eligible for the pension; and part-time work in the lead up to state pension age is not widespread. However, since 2009 it has become possible to combine paid employment and pension incomes by re-joining the labour market (Principi et al. Reference Principi, Checcucci, Di Rosa, Lamura and Scherger2015). The state pension represents 72 per cent of the income of retired Italians – notably higher than in the USA (30%) and United Kingdom (UK) (50%) (House of Commons 2015). Despite this diversity in state pension receipt, the average income of older people (age 65+), relative to the overall population, is similar in Italy and the USA (above 93%) while at around 80 per cent, UK pensioners are worse off than Italian and US pensioners (OECD 2013).

England and the USA represent a liberal welfare model, characterised by de-familialisation with a broader role for private care (Bambra Reference Bambra2004), which enables individuals to participate in society (work, volunteering, other activities) and be independent from the family (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen1999). However, there are differences between these two countries concerning the transition from work to retirement (Lain Reference Lain2011).

In the UK (including England), it is not possible to draw a state pension before state pension age which, in 2014, was age 65 for men and 62 for women (to increase to age 68 for both by 2046). Most individuals in the UK do not rely exclusively on the state pension however, in 2013 62 per cent of pensioners were in receipt of an occupational pension and 17 per cent in receipt of a personal pension (Pension Policy Institute 2015). The UK tax, benefit and pensions systems permit individuals to work whilst drawing state and/or private pensions, providing a financial incentive to continue working beyond state pension age. In addition, an early retirement deterrent was imposed in 2010 at which point the age threshold for drawing a company or personal pension increased from 50 to 55 years. Defined-benefit pension schemes, which have long been associated with early retirement, have all but disappeared. In 2006 age discrimination legislation was introduced and in 2011 the default retirement age was abolished so older employees are no longer expected to retire once they reach state pension age. The UK also introduced measures in 2004 to allow pension drawdown without first having to leave employment – this makes shifting to part-time employment more affordable. Other measures introduced to promote flexibility include the 2014 Flexible Working RegulationsFootnote 1 which extend to all employees the statutory right to request flexible working such as reduced hours, flexitime or working from home (although employers can refuse requests on business grounds).

In the USA, a variety of pro-work incentives has impacted older Americans since the early 1980s (Cahill, Giandrea and Quinn Reference Cahill, Giandrea, Quinn, George and Ferraro2015). In 1986, mandatory retirement was eliminated for the majority of US workers. The Full Retirement Age of the public pension system, known as Social Security, increased gradually from age 65 to age 66 for those born from 1938 to 1943 and is scheduled to increase further, in stages, to 67 (Congressional Budget Office 2001). Other incentives include: the Delayed Retirement Credit and elimination of the Social Security earnings test for individuals who work beyond the Full Retirement Age. While approximately one-half of the US workforce has participated in an employer-provided pension over the past 35 years, the type of pension plan has shifted dramatically away from defined-benefit plans to defined-contribution plans. This switch has left older Americans more exposed to both investment risk and longevity risk later in life, and created an incentive to work longer to insure against both (Munnell Reference Munnell2014).

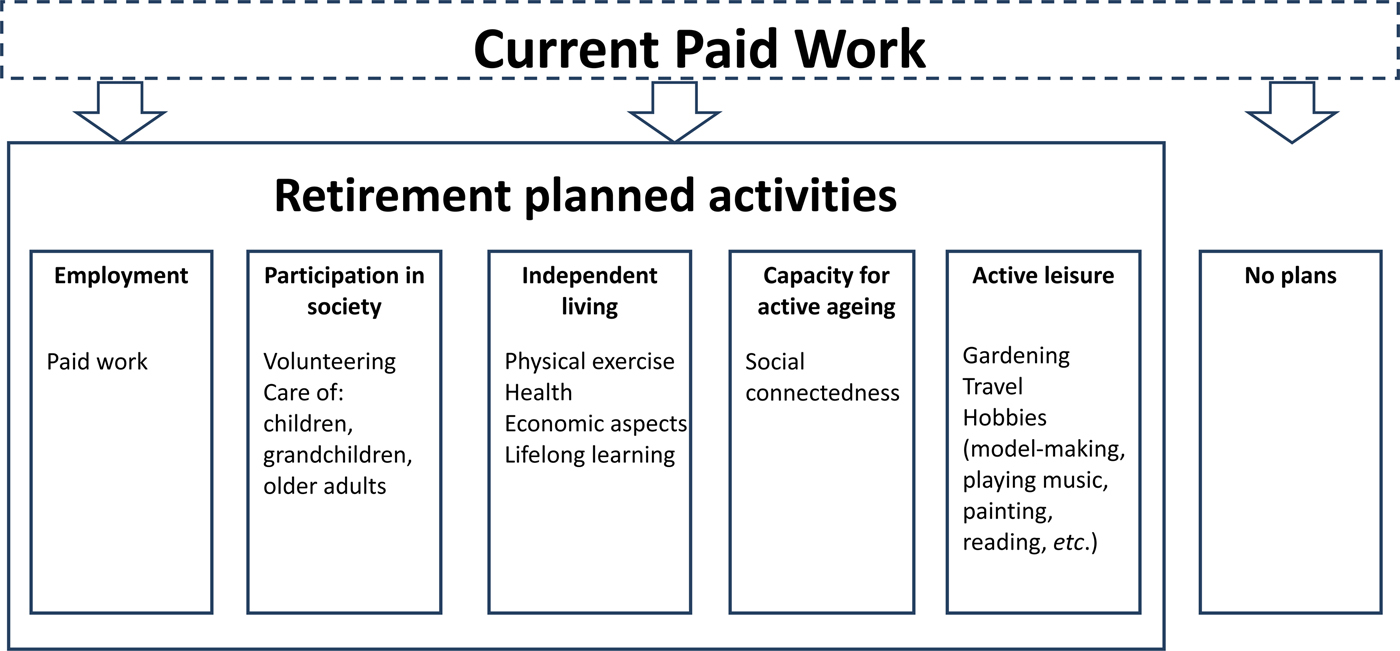

Differences between the three countries concern also the general level of active ageing based on AAI scores (see Table 1). The AAI index includes indicators representing four domains (Zaidi et al. Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Hofmarcher, Lelkes, Marin, Rodrigues, Schmidt, Vanhuysse and Zolyomi2013): employment, participation in society, independent living and capacity for active ageing. The domain of employment includes employment rates of older workers from 55 to 74 years; participation in society is related to voluntary activities, informal care of children, grandchildren and older adults, and participation in political activities. The independent living dimension relates to physical exercise, lifelong learning, income and access to health care; and the dimension of capacity for active ageing includes, among other indicators, social connectedness (meeting friends, relatives or colleagues), use of information and communication technology (ICT) and education.

Table 1. Active Ageing Index in the United States of America (USA), Italy, the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU28)

Note: 2014 scores for Europe; 2012 scores for the USA.

Sources: Zaidi (Reference Zaidi2014); Zaidi and Stanton (Reference Zaidi and Stanton2015).

Overall, the highest AAI score is found in the USA and the lowest in Italy (Table 1). While the USA (especially) and the UK rank very well in the employment dimension, the Italian value is under the European average. On the contrary, Italy has the highest value in the dimension of participation in society, mainly due to the role of Italian older people in informal care activities, although their involvement in volunteering is more marginal than in other countries. As for independent living and capacity for active ageing, US and UK values are higher than in Italy (Zaidi Reference Zaidi2014; Zaidi et al. Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Hofmarcher, Lelkes, Marin, Rodrigues, Schmidt, Vanhuysse and Zolyomi2013).

Methods

A total of 133 older workers who planned to retire within the next 10–12 months were interviewed between May 2014 and early 2015. In this study, retirement is self-defined and in all countries this was associated with individuals being eligible for a pension (state, occupational or private) while simultaneously leaving current employment.

Procedure

Participants were selected on the basis that their proximity to retirement would lead them to have a focus on plans and expectations for this transition (Evans, Ekerdt and Bosse Reference Evans, Ekerdt and Bosse1985). Respondents lived primarily in urban areas (but some were from rural contextsFootnote 2 ): 55 across England (mean age 61), 40 in Central Italy (mean age 60) and 38 in North West USA (mean age 62). Purposive sampling techniques were deployed to achieve diversity in terms of: relationship status, household composition, income group, age, gender and occupational background (to include people from sedentary, stressful and physically challenging jobs). Participants in each country were screened through a recruitment agency and selected on the basis that they were employed and working full-time (30 hours or more, or at least four days per week). Participants were also selected on the basis that they were retiring for non-health reasons. This decision stems from the fact that this study is focused on generally exploring whether the plans of older workers on the cusp of retirement are in line with the active ageing agenda, as opposed to exploring the interplay between particularly poor health conditions and the retirement transition.

Interviews were carried out in the native language using a common semi-structured topic guide, which explored a range of issues including: motivations around the decision to retire, plans for activities in retirement and expected changes to lifestyles (social activity, diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption).Footnote 3

Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and anonymised. Data management and analysis was initially conducted using NVivo or MAXQDA11 and coded thematically according to interview topics. Broader themes were identified at this preliminary stage, such as ‘retirement motives’, ‘worries’ and ‘plans’. A subsequent round of analysis for this paper categorised responses by the active ageing theoretical framework, including the AAI, plus additional emergent themes about expectations for retirement. During the final stage of our analysis, the data were reduced and compiled in a framework matrix (Ritchie Reference Ritchie2013), using a spreadsheet to display data themes across columns and respondents by rows. A summary of respondent data for a theme was entered into each cell. The matrix display enabled systematic comparisons across respondents. Dominant themes were summarised by country.

Although based on small samples, and therefore not representative of the wider Italian, US and English populations, the findings can provide insights into how the retirement transition is anticipated in relation to the active ageing principle.

Results

We found examples of retirement plans in each of the four dimensions considered by the AAI. Additionally, two further categories emerged from participants’ narratives: planned activities in the realm of active leisure that are mostly focused on the individual, rather than the societal, level (i.e. active leisure), and there were pre-retirees without specific retirement plans. Figure 1 shows the range of activities respondents anticipated and hoped would occupy them during retirement.

Figure 1. Transitioning from paid work into various retirement activities: pre-retirees’ plans.

Employment

Paid work in the labour market is an important dimension of active ageing. Among US interviewees, a continued orientation towards work was a dominant theme – with less emphasis on a retirement exclusively of leisure. Among English interviewees, there was a distinct sub-group whose plans for retirement remained employment-oriented, suggesting they would be returning to some form of paid work either in a new job, with their old employers under new arrangements or on a self-employed basis. By contrast, very few of the Italian interviewees expressed the intention of continuing to work after retirement.

Among the US respondents who planned to remain active in the labour force in some capacity, most expected to do so for non-financial reasons, stating that their free time and opportunities were limited in their full-time jobs, and they welcomed retirement as an opportunity to pursue a different line of work, often on a part-time and flexible basis, as in the following example:

I do plan on working … and I want to retire because I want to do something different and I'm kind of tired of doing the same kind of job as I'm doing with the sitting, the sedentariness of it all … I'm obviously not going to switch companies to another one and do the same thing because that wouldn't make sense and as I say I just want to have a change in my lifestyle. Not style but my life. (US13, female, age 64)

US interviewees with less generous pensions indicated that the additional income from work was a key reason for them to remain employed.

Although work oriented, a sub-group of English interviewees still largely perceived themselves as retiring as they would be drawing a pension and returning to work for far fewer hours and with a sense that their work–life balance had completely shifted – a ‘gradual retirement’ trajectory. However, their job preferences may not be realistic in terms of employment opportunities. There was a requirement that the job and hours would very much need to be on their own terms, involving few hours or days and considerable flexibility such as annualised hours with the option to turn down work if it ever clashed with leisure preferences, as in the following example:

I don't really want to be tied down to anything too rigid because I do want to travel … it might be that I can find something that I could do one day a week for six months and then have six months off to travel … or something that is flexible that I can do annualised hours so I can do a couple of months at the beginning and then have a block off and then a couple of months … so I will look around and see what there is. (EN42, female, age 55)

The desire to join the labour market again was much less evident in the retirement plans of the Italian interviewees. The main explanation for this was that having worked all their lives, they have had enough and wanted to do other activities:

I will retire because, finally, after having accumulated 42 years and six months of contribution I'm entitled to retire, and I'm ready to do other things in my life, besides work! (IT23, male, age 60)

Many Italian respondents perceived stepping aside as a moral duty, to make room for the huge number of unemployed young people.Footnote 4 Almost all the interviewed Italians were retiring before the state pension age, by means of a public early retirement scheme.

Participation in society

AAI indicators of participation in society include, among others, voluntary work and care of children, grandchildren and older adults. Voluntary work was anticipated among all interviewees, while an expectation for informal caring responsibilities was more commonly mentioned among the Italian respondents.

Voluntary activities

A variety of forms of unpaid work in the community were anticipated by interviewees in all three countries. Some people had already been carrying out these roles while in employment and planned to increase the intensity of the activity while others were considering volunteering as a means to develop skills or use existing skills, to engage socially and maintain a routine in their lives. For example, among the Italian interviewees, some had already scheduled commitments, including: Caritas (a Catholic voluntary organisation supporting people with poverty-related needs), emergency services such as ambulance drivers, churches, recreational centres and civic museums. Sometimes, the wish to join volunteering arose at the end of a caring experience. For example:

I would like to volunteer in an association dealing with Alzheimer. Unfortunately, because of my mum who suffered this for seven years, I have had the opportunity to know different associations of this kind. I realised that especially in these times, family alone is not enough and it is very important help from an external body. (IT08, female, age 58)

Among the English and the US respondents, voluntary work was preferred to paid employment by some because it was perceived as offering greater flexibility. In some instances, opportunities in the voluntary sector also allowed people to take on roles and responsibilities and use expertise they felt would not have been available to them in paid positions. One English man, aged 64, had set up a voluntary position to start once he had retired which would allow him to use skills which he was not currently deploying in his paid job. He was excited at the prospect of being more fulfilled as a volunteer than in the job he had been performing for the past ten years. The motivation behind unpaid volunteering for those who expressed an interest in pursuing this option was also to promote the social good by contributing their time to a just cause:

There's a lot of people that say ‘I don't know what I'm going to do if I retire’ and I'm like ‘well for crying out loud there's tons of volunteer work that's needed, extreme, you know’ … There's a lot of older people, there's a hospital, there's reading for kids, there's, you know, a lot of disability veterans, you know, you name it it's out there. That's one reason why I look forward to retirement. (US33, female, age 60)

Care for children, grandchildren and older adults

Another group of respondents discussed their commitment to informal caring activities. Retirement can allow for more time to devote to parents, grandchildren, spouses or children in poor health. A family orientation was particularly strong among the Italian interviewees, for both men and women. Italian interviewees discussed the future in relation to supporting the family, spending more time together or helping adult children in numerous ways. Many had grandchildren or older relatives in need of care. In Italy, family relationships are very strong, are an integrated part of daily life routines (for instance, care-giving, grandparenting activities, ‘extended-family lunches’ on Sunday, etc.) and, despite the fact that things are gradually changing, these family-oriented relationships, co-dependencies and activities are still culturally taken for granted and structure daily life (Di Rosa et al. Reference Di Rosa, Melchiorre, Lucchetti and Lamura2012; Principi, Chiatti and Lamura Reference Principi, Chiatti, Lamura, Principi, Jensen and Lamura2014). Several interviewed older workers anticipated the grandparent role and in some cases related plans were quite structured, as in the following example:

In my mind, I know exactly how I'll spend my days: from the first day of retirement I will drive my older granddaughter to school here, in [xxx], by car. Afterwards, at 3 pm, I will go to [xxx, which is 15 kilometres from the first place], where my other daughter lives, and I will look after my grandson while his mum will be working. (IT26, female, age 59)

A less positive aspect of the strong family orientation is that sometimes informal elder-care was felt as a constraint, preventing other options. In the following case, for instance, the need to increase the level of informal care to older family members was the main reason for retiring:

I would like to relax and distract myself … pursue my hobbies such as walking, which I really enjoy. Perhaps travel … However, none of this is possible now because of my older relatives. All my plans are currently on hold. Let's say they are an unrealistic utopia. (IT38, female, age 62)

In contrast, among English interviewees there were no examples of individuals choosing to retire in order to care for older relatives. There were instances where people envisioned balancing caring roles with leisure activities but, similar to their views on future paid work, on their own terms. These respondents felt they had done their bit, really enjoyed being grandparents but did not wish to be relied on to care apart from on an intermittent, occasional basis, as in the following example of a man who hoped to spend his retirement years free of constraints in order to travel:

I don't know why but when you're grandparents and you're at home and they know you're at home ‘oh, by the way, could you just look after so and so for the day, or a couple of days’ … the wife would have them all the time but like I want to do things, I've had my children, it's their job now. I don't mind occasionally but weeks at a time because of holidays, if I'd got the money I'd say put them into one of them preschool things and whatever. (EN17, male, age 59)

The experience of the US respondents with respect to care-giving resembled that of the English respondents. Several US respondents were looking forward to spending time with their grandchildren in retirement as well, but not as a care-giver per se.

Independent living

Independent living focuses on preventing health decline in older age by empowering people to remain in charge of their own lives for as long as possible while ageing. Key elements of this dimension include: physical exercise, income and lifelong learning activities. Physical exercise and health-related plans were frequently raised by interviewees in all three countries. Some US and English respondents were worried about their income during retirement, whereas this theme was not identified among Italian respondents. Participation in learning activities was also anticipated among the US and the English interviewees, but less so by Italian respondents.

Physical exercise and health

Plans for healthier lifestyles, improved diets and increased physical activity, in particular, were commonly expressed by interviewees in all three countries. For example, many Italian respondents were particularly eager to improve their diet after retirement, by cooking and eating healthier foods. In the following case, a woman defined herself as muddling through the week without organising or planning and she was unhappy with this rather ad hoc approach because she just grabs what she sees without thinking carefully about nutritional needs. She anticipated changing these habits once retired:

Yes, work affects my diet. When I am off work my diet is more balanced as I know from the early morning what to cook for lunch … and for dinner … Instead, when I work I can't organise myself; I open the fridge and grab whatever is in it, so eat badly … I think I will have a more balanced diet after retirement. I aim to lose weight. (IT26, female, age 59)

In some instances, choices after retirement were seen in terms of a trade-off between health and ‘productive’ opportunities. In the following example from England, an opportunity to become actively involved in local politics was seen as exciting but, as a stressful and time-consuming role, it was seen as potentially problematic for his health:

Well I don't know whether I've rushed into possibly standing for the local authority. Somebody died, you immediately say who is going to get his job and I thought ‘well I'm retiring’ and so I'm torn. I want to lose weight. I want to maintain my fitness. I don't want to be responsible for other people. In some ways being a councillor might not be the best route. (EN41, male, age 59)

Many of the interviewees across all countries hoped to pursue a wide range of sporting activities, motivated by a desire to maintain or improve health once retired, or as a useful means of occupying newly freed time. It was also acknowledged that sport is a good source of social activity, often being enjoyed with friends, family and in clubs. There were several examples though of individuals who were keen on sporting pursuits but who had lost friends to participate with. Living alone and having a restricted social network were therefore risk factors in relation to physical activity. More generally, people assumed there would be a natural increase in their physical activity, because they would have more time, and be less tired, once they were no longer at work.

Cost was raised as an obstacle by some on lower incomes across English respondents. Municipal facilities such as swimming pools or gyms are widely available but can be overcrowded, some people did not feel comfortable in gyms or leisure centres due to their age and cleanliness was questioned. The alternatives – private membership clubs and facilities – are also widely available with a large health-related leisure industry, but costs can be prohibitive. A final obstacle raised by English interviewees was the weather. With cold wet winters several respondents indicated that they ‘hibernate’ during the winter months and feel unmotivated to engage in physical activity. The following quote summarises this concern:

You see the good weather and you think oh my goodness, if I retire I can go on long walks … but, when it's dreary and it's miserable, I think what am I going to do at home, I'll go potty. (EN01, female, age 60)

Examples of these sorts of obstacles were not raised among the Italian and US respondents. In Italy there are few subsidised municipal facilities (e.g. swimming pools), and the Italian interviewees seemed more oriented towards free open-air activities. The obstacle to physical activity most widely reported in the US interviews was a lack of time due to work hours and, to a lesser extent, weather. North West USA, where the interviews were focused, has a lot of open space, trails, walkways, a comprehensive network of cycle paths and parks, all of which are free.

Perceptions of economic situation

In relation to perceived adequacy of income, distinct responses and attitudes were evident when comparing Italian participants with respondents from the USA and the UK. Each of the three samples included a range of incomes with the expectation that during retirement incomes would be reduced. Many US and UK respondents were quite worried about losing income (aligning with expectations for work after retirement), as illustrated by one US interviewee:

I have no apprehensions about retiring except for income of course, you know, everybody who retires is worried about income and actually I think that's about it. (US33, female, age 62)

Although the Italian interviewees were aware their income would be reduced in retirement, they felt they would get by and plans to improve retirement income were not common. Instead, they stated that they would cope on a reduced income, holding the view that money is less important than family and good health. For example:

I will not have enough money but I do not mind! … If it's the first day of the month and I'll have to wait until the 10th to receive my pension, what shall I do? I will see what's in the fridge … if the car needs fuel I will not use it… But I will not start working again! (IT26, female, age 59)

While most US interviewees had a very positive outlook of retirement generally, many expressed some concern about finances, such as what might happen in the case of a catastrophic illness that would drain their financial resources. The costs of health problems in later life were not raised by English or Italian interviewees, reflecting their universal coverage of tax/national insurance-funded health services. Within both the US and English interviews there was a notable divide in attitudes between employees with and without defined-benefit pensions, with the former less anxious about money.

Lifelong learning

Retirement plans concerning learning activities were not common among the Italian interviewees although a few individuals mentioned the wish to attend courses at the University of the Third Age (with English and ICT being of particular interest). By contrast, learning opportunities in retirement were a common theme among English and US interviewees. On the whole, the courses favoured were oriented towards creative activities, e.g. photography, ICT, musical instruments, art and design, and languages. In some cases, courses were chosen due to their content, either wishing to learn something new or return to a skill held in the past; in other instances, the main motivation was to meet people and remain socially engaged.

Key obstacles cited by English interviewees, however, included cost and course availability. Options were described as quite limited by one respondent who lived in a small town and who would need to travel a fair distance to access courses of interest to her. In terms of cost, several English interviewees cited this as something that would determine whether they pursued further learning, as in the following example:

I've been accepted for the training course … I'm still wondering whether it's worth it … it's quite expensive training … two thousand pounds and it's only like three weekends. (EN41, male, age 59)

Capacity for active ageing

The fourth domain of the AAI captures the capacity and enabling environment aspects of active and healthy ageing. Although it also includes aspects such as life expectancy and educational level, we concentrated on individual activities in relation to this dimension, that is the capacity to remain socially connected (meeting friends, relatives or colleagues).

Interviewees in all three countries expressed the view that their working lives had squeezed the time available to spend with family and friends, and retirement was seen as finally providing the opportunity to re-prioritise relationships. The wish to increase one's social network was often mentioned as a further aim of other activities discussed above, for instance volunteering, sports or educational activities.

Losing touch with work colleagues, however, was one concern raised by the Italian respondents, in particular, who spoke despondently of the loss they will feel once retired, without the companionship of workmates:

After retirement I will have fewer contacts, because we will not see each other at work, we will not have the opportunity to think of something to do together. (IT17, male, age 65)

It is not only work friendships that will be missed but also the casual social encounters and exchanges in the workplace with colleagues and clients, whether positive or not, as highlighted in the following example:

It [work] gets me out, I do meet people, however hideous they can be. (EN01, female, age 60)

Active leisure

Interviewees in all three countries anticipated their retirement in terms of activities which are not considered by the AAI. These were mainly leisure activities typically conducted alone which nevertheless contribute to the mental or physical wellbeing of individuals (Walker Reference Walker2011). Some pursuits can be classified as physical activity such as gardening, home-making and work to improve the home, while other hobbies are more sedentary, including model-making, music (playing instruments, composing songs), painting, reading, etc. Often these were creative activities carried out in younger age and set aside at a certain point of life due to work commitments. For example:

When I was young I studied violin and guitar, so the music has always been my great passion that I tried to cultivate in my spare time … This passion will absorb a considerable part of my time when I retire and this makes me feel good. (IT23, male, age 60)

Among the US interviewees, leisure pursuits were anticipated alongside other ‘productive’ pursuits. A noted pattern for this group was the wish to leave a career job, take their pension and channel their energy differently, towards more meaningful work, volunteerism or just for a change. More often than among Italian and English interviewees, retirement among US interviewees was perceived as a ‘second act’, with new challenges and fresh opportunities rather than, as described by Moen (Reference Moen2005: 203), a permanent exit associated with a ‘second childhood of boundless leisure’. A small group of US respondents, however, did plan to pursue a path of full-time active leisure in retirement. With the exception of one individual who reported being well-off financially and without children, these individuals were public-sector workers with generous pensions who viewed retirement in the traditional sense – as a one-time, permanent exit from the labour force.

No retirement plans and fears about passive retirement

Most of the individuals in the study expressed clear ideas of how they expected their life to change or had broad ideas about the shape their life would take and the activities they hoped to extend or adopt afresh. However, some interviewees had given little thought to how their lives would transform and what might occupy their time, an attitude reflected as ‘I just want to give up and see what happens’. Trepidation about the unknown was a common theme, particularly when concrete plans were not formed. For these individuals, retirement was discussed less as the beginning of something new and more as an ending:

I started work at 15 so that's 51 years of working and all the time you're striving to do better and earn money and more progress. Then all of a sudden it all finishes, bang, and there's nothing. (EN08, male, age 65)

I think that's the fear of retirement, isn't it, something stopping, everything stops, all your habits, all your friends, all your patterns of behaviour stop completely. (EN07, female, age 57)

To be honest, until a few months ago I was really excited about my imminent retirement, but now I am starting to feel a little bit stressed … I do not know how my life will change after retirement. I would say, really … empty mind. I have not thought about it … because I've been working for 42 years now and have always been doing the same things. (IT35, female, age 57)

Expectations of a fully passive and inactive retirement (described as retreaters by Schlossberg Reference Schlossberg2004) were uncommon among the interviewees across the three countries. On the contrary, and in line with the active ageing concept, passive retirement and social exclusion were seen by many as undesired risks to avoid. For example, time ‘slipping away’ was a concern, as was the possibility of sliding into a retirement of decline and ‘becoming a vegetable’. The following quote exemplifies this anxiety:

There's such a danger, when people retire they do nothing, they just vegetate. That's a big concern to me, that's the last thing on earth I'd want to do. (EN19, male, age 65)

A number of interviewees similarly expressed concerns and fear of becoming isolated after retirement. This fear encouraged many to plan to join voluntary organisations, recreational clubs and so on, in order to maintain or nurture new social relationships. Others, however, were quite worried that they would not be able to replace their social relationships and may become a burden:

My greatest fear is to become a burden for society, for this reason I will manage to join volunteering. (IT15, male, age 65)

I dog and house sit on the side now and I'll probably continue in some fashion try to earn supplemental income … That's definitely something I want to start planning more of because I can see where I could get depressed if I don't have something going. (US02, female, age 58)

It should be noted, however, that some respondents, particularly among the Italian and English samples, viewed retirement in rather more traditional terms with a desire to slow down, unwind, relax and potter:

Stopping in bed till 10 o'clock of a morning, get up and if it's lovely I'll sit in the garden with a cup of tea, I wish I could do that … a slower pace. (EN17 male, age 60)

In general, I would like to live in a different way … First of all, without schedules. And this would be the ‘biggest lust’ after more than 40 years of work. Then, I do not know … spend the winter somewhere [else], in a warmer country than this … to enjoy some months at the seaside, or camping … In other words, without time-scales … [I like] the idea of time passing slowly. (IT21, female, age 57)

Discussion

The aims of this qualitative study were to understand how plans for retirement expressed by interviewees in Italy, England and the USA were linked to the concept of active ageing, and to identify possible differences between country groups reflecting their distinct cultural values, welfare regimes, and recent employment and pension reforms. These variations in culture, policy and attitudes highlight how the experience of ageing can vary according to where you live. Our study found that plans for retirement were mainly consistent with the active ageing perspective. Although an expectation for a fully ‘passive’ retirement was not a common theme, there were examples of individuals seeing retirement as a time to wind down and take a more relaxed pace of life. There were also a few examples of individuals from England and Italy who feared that retirement would be an ending and for whom the future was opaque, with the possibility of new social roles far from clear. In relation to the different dimensions of active ageing considered by the AAI (Zaidi et al. Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Hofmarcher, Lelkes, Marin, Rodrigues, Schmidt, Vanhuysse and Zolyomi2013), we found several differences between respondents in the different countries; these revolved primarily around the dimensions of employment and participation in society. Differences were also found relative to plans for individual active leisure, although the latter is not considered by the AAI.

Whereas paid work was a dominant expectation for US interviewees, for Italian respondents retirement was considered a one-time, permanent break from paid work, explained in large part by the Italian institutional setting. In contrast to the US and English respondents, Italians must fully withdraw from the labour market in order to start receiving their state pension (Principi et al. Reference Principi, Checcucci, Di Rosa, Lamura and Scherger2015). Thus, in a climate of pension system reforms with a gradually increasing retirement age, most of the Italian interviewees chose to retire ‘as soon as possible’, before new reforms locked them into the labour market for longer. This is in line with results showing that European older workers generally wish to retire before the state pension age (Hofäcker Reference Hofäcker2015). In order to increase the participation of older people in the labour market, Italian policy makers are advised to introduce greater flexibility both in terms of the availability of part-time hours and in options for state pension drawdown combined with employment. Italians were also motivated by a perceived need to make way for the younger generation – yet evidence demonstrates that older workers do not crowd out younger workers (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Blundell, Bozio, Emmerson, Gruber and Wise2010; Eichhorst et al. Reference Eichhorst, Boeri, Braga, De Coen, Galasso, Gerard, Kendzia, Mayrhuber, Pedersen, Schmidl and Steiber2013) and, over the long term, increasing employment can lead to economic growth, increased demand and a further increase in jobs.

Insofar as financial need was a common motivation for aspirations to continue working, it should be noted that the role of employment within the active ageing agenda may be multifaceted. Our results suggest that high employment rates cannot simply be read as a positive outcome from the perspective of individuals. In some cases, in the absence of financial constraints, older people would invest their future in activities other than work. When continued work is experienced as a constrained choice, this may compromise quality of life, especially if individuals struggle to find the work they need or are pushed into the casual labour market, characterised by low pay and poor terms and conditions. Quality of employment must therefore also be taken into account. This is important in contexts such as the USA and the UK, where pension income is much lower than the previous wage (House of Commons 2015). Hung, Kempen and De Vries (Reference Hung, Kempen and De Vries2010: 1387) similarly note the importance of recognising that employment later in life may be a culturally relative goal – in Asia, older people identify healthy or successful ageing in relation to close family support and ‘enjoying a leisurely late life’, with continued working in old age anathema to life satisfaction.

Expectations to provide informal care for others were common among the Italian interviewees. This orientation is reflected in national data which show that the incidence of active grandparenting is far more widespread in Italy than the USA or UK (with around one-quarter of US and British older people aged 55–74 caring for grandchildren at least once a week compared with over half – 54% – in Italy) (Zaidi et al. Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Hofmarcher, Lelkes, Marin, Rodrigues, Schmidt, Vanhuysse and Zolyomi2013; authors’ calculations from the Health and Retirement Study). Across all countries there were interviewees who viewed caring roles less as an opportunity for a varied and active retirement and more of an obstacle to other preferred activities. While most interviewed people were delighted at the prospect of spending more time with grandchildren, concerns were expressed that as retirees they would become expected to perform caring roles on a routine basis now that they were not productive in the labour market. These findings raise questions in relation to the AAI which recommends increased promotion of caring roles as an integral component of active ageing, especially given the mixed evidence relating to physical and psychological benefits of caring among previous studies (e.g. Coe and van Houtven Reference Coe and van Houtven2009; Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Neuberger and Haberkern Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2013). The findings suggest that informal carers should be supported more adequately by national and local governments.

In terms of capacity for active ageing, increased contact with family, friends and other people were central to the plans for retirement for interviewees in all three countries. Several of them, however, expressed concern that contacts with work colleagues would decline after retirement. Employer initiatives to help their staff make the transition to retirement would, in these instances, be welcomed and could benefit both retirees and employers alike. Keep-in-touch schemes with retired workers, for example, could help retirees to maintain contact with old friends and colleagues, while at the same time providing employers with a link to experienced ex-employees who may in the future be interested in work on a casual or consultancy basis, or to provide temporary cover in response to staff absence, maternity leave or holidays. In the UK, there are some existing initiatives along these lines among large organisations which organise social activities for their former staff (Bazalgette, Cheetham and Grist Reference Bazalgette, Cheetham and Grist2012). The potential value of workers’ clubs will increase as opportunities for informal social contacts elsewhere decline. For instance, in each of the three countries austerity measures have been introduced which starve voluntary-sector organisations of funding and threaten community hubs such as libraries. Throughout the UK, high streets which were once vibrant and diverse and which also acted as social hubs are in decline, with shopping moving out of town or online, leaving behind charity shops, betting shops and chain stores devoid of character (Portas Reference Portas2011). The importance of local communities for ageing populations is also recognised across the USA with the emergence of support for a range of age-friendly community initiatives (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2015). Schemes such as ‘walkable communities’ (Golant Reference Golant2014) are devised to improve social and physical environments which promote health, wellbeing and the ability to age in place (Greenfield et al. Reference Greenfield, Oberlink, Scharlach, Neal and Stafford2015: 44). Their scale and scope remain limited, however, due to minimal federal funding and leadership (Scharlach Reference Scharlach2012) as the USA faces the same austerity pressures as the UK and Italy.

Most notably among the English and Italian interviewees, a widespread wish for a retirement of active leisure was also found. While these activities are not considered within the AAI, they are positive for the health, wellbeing and life satisfaction of older people (Walker Reference Walker2011). According to Jun (Reference Jun2014), just as individuals need to achieve work–life balance during their working years, later in life there is a need to attend to ‘life-balance’, i.e. how time is balanced between constraints/committed time (work, caring, volunteering, cleaning, cooking), regenerative time (sleeping and eating) and discretionary time (including leisure pursuits), as either too much or too little discretionary time can be bad for wellbeing. The AAI tends to focus on ‘committed time’, while the value of discretionary time should also be acknowledged, as reflected in the plans and aspirations of the English sample, in particular, who were more oriented towards leisure. The Italian respondents were similarly leisure oriented although expectations in terms of caring commitments were stronger.

Consistent with previous studies (Nuttman-Schwartz Reference Nuttman-Schwartz2004), a dominant theme among interviewees was the explicit acknowledgement that retirement presents a risk of undesired withdrawal from society. A concern was voiced that there was a need to guard against the emergence of a more passive lifestyle. While some were approaching retirement with a relaxed attitude, for many others the idea of retirement provoked anxieties about ‘vegetating’ or being a burden to society. These fears suggest that more support should be offered at this life-stage to provide assistance in making plans and to increase the provision of opportunities for self-fulfilment and realising aspirations during retirement. Awareness of retirement preparation events or courses was non-existent among the Italian interviewees, and most provision in the UK and USA is focused on financial planning and instrumental advice. To tailor these programmes better to individual experiences (Hanson and Wapner Reference Hanson and Wapner1994), services could be provided by companies for their workforce.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrated that, although some dominant themes differed within each country (e.g. more work-oriented plans from US respondents and more care-related plans from Italian respondents), retirement plans of the interviewees were largely consistent with the active ageing policy agenda. The study also revealed retirement expectations with an individual leisure focus. In essence, although it is important to measure the untapped potential of older people for active ageing from a productivist perspective, to ensure that latent demand for such opportunities are met, this study suggests the importance of also measuring other dimensions of retirement which have implications for the quality of life and wellbeing of older people. Future studies might deal with this challenge by including indicators of active leisure, and by rethinking the weight of some of the current indicators, such as employment and informal care. One potential weakness of the AAI is that it may implicitly encourage older people to hold on, for as long as possible, to priorities and productive lifestyles characteristic of earlier life-stages. The risk is that this approach fails to recognise that quality of life and wellbeing of older people may also depend on a shift in pace, rhythms and focus.

The results also suggest that more efforts both at the macro- and meso-level seem to be needed to support older workers to make plans as well as to fulfil them. Among possible initiatives, regulations allowing a more gradual retirement could be useful to increase options for extending working life in Italy, and in all countries companies could more actively support workers in their transition to retirement, including pre-retirement courses and schemes designed to promote links between former (retired) employees and their old colleagues.

One limitation of this study is that the project was designed to investigate the transitions, journeys and outcomes of individuals who were not forced to retire on the grounds of ill health or disability. The issues and challenges facing ill-health retirees are distinct, and warrant focused detailed study. These individuals may have different perspectives on paid work, caring responsibilities and leisure during retirement. Further research should consider different national policies on health care and community support systems, how they may be factored into retirement decisions among older workers with major health problems and how they may come to bear on plans for retirement activities. Furthermore, being a qualitative study, results cannot be generalised to the wider Italian, US and English contexts. In light of the challenges identified above, further research is needed to explore and refine the general and context-specific relationship between retirement plans of older workers and the active ageing agenda.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the British Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Cross-council Programme (LLHW). The LLHW Funding Partners for this award are the Economic and Social Research Council and the Medical Research Council (grant number ES/L002884/1). We would also like to acknowledge and thank the research participants who kindly gave up their time and shared their experiences and thoughts.