Immigration is one of the most contentious and divisive political issues (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2019; Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2022), posing fundamental challenges to contemporary mainstream parties in Western democracies. Both mainstream left and mainstream right parties are under pressure to find adequate position-taking responses given that their traditional electoral coalitions are divided on the issue (Hadj Abdou et al. Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2022; Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014) while far-right populist parties (FRPPs) are enabled to exert their ‘issue ownership’ to garner substantial amounts of electoral support (Bale et al. Reference Bale2010; Meguid Reference Meguid2005). It is now well documented in the literature that mainstream parties commonly seek to curb their own electoral decline and fight the competition from the far right by adopting more restrictive policy positions on immigration and integration issues (e.g. Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Bale Reference Bale2008; Dahlström and Sundell Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012).

Recent real-world examples of this are manifold. In the run-up to the 2024/25 UK general election, for example, the ruling Conservative Party increased considerably the income threshold for British citizens and foreign residents to bring foreign family members into the UK (Booth and Goodier Reference Booth and Goodier2023). In France, a new hardship immigration law was initiated by Emmanuel Macron's centrist government in late 2023 to deny new immigrants certain social security benefits, which was hailed by the far-right Rassemblement National as an ‘ideological victory’ (Chrisafis Reference Chrisafis2023).

However, little is known about the actual political consequences of such position-taking. While existing research has mainly sought to understand whether more restrictive immigration policy positions can actually recapture renegade voters who have defected to FRPPs (e.g. Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2021; Dahlström and Sundell Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012; Down and Han Reference Down and Han2020; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2022), it has recently been highlighted that much of this body of research has produced ‘inconclusive, contradictory or null results’ (Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022: 951).

Moreover, as yet there is no research on the potential consequences of such position-taking for fundamental democratic attitudes in the citizenry. In particular, political trust is a considerable blind spot in this line of research. Bringing trust into the picture is not only of crucial normative importance, but also analytically fruitful.

Normatively, understanding the correlates of public political trust is highly relevant given that political trust is widely considered a key currency of liberal democracy, inextricably entangled with the legitimacy that citizens attribute to elite actors and the wider political system (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Marien and Hooghe Reference Marien and Hooghe2011). Analytically, the focus on party position-taking and political trust might also help to understand better the role that political distrust plays for far-right voting. The literature on immigration-related trust suggests that, due to their dissatisfaction with how political elites handle immigration issues, immigration-sceptical citizens tend to have higher levels of political distrust than immigration-welcoming citizens (e.g. McLaren Reference McLaren2012). Moreover, political distrust is commonly invoked as a key individual-level driver of far-right voting (e.g. Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018). Therefore, immigration-related distrust and FRPP support might be two sides of the same coin, shaped by mainstream party behaviour.

Against this backdrop, the present article draws on spatial theory (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2020; Downs Reference Downs1957; Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990; Stecker and Tausendpfund Reference Stecker and Tausendpfund2016) to shed light on the role of political (dis)trust as a consequence of mainstream party position-taking and a precursor of far-right voting. It argues that citizens develop feelings of political (dis)trust based on the instrumental evaluation of where their own policy position locates relative to that of mainstream parties. In particular the position-taking of centre-right (rather than centre-left) and government (rather than opposition) parties are considered crucial reference points due to their location in the immigration policy space and policy influence. Thus, whereas immigration-sceptical citizens should react to tougher immigration positions of those parties with a boost in their political trust levels, immigration-welcoming citizens should respond with a trust deterioration. By extension, political distrust becomes less strongly associated with far-right voting due to more distrusting citizens on the immigration-welcoming end of the spectrum.

Empirically, the study combines party-level data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) project (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly and Bakker2022) with individual-level data collected as part of the European Social Survey (ESS) across 14 Western European democracies in the period 2006–2018. Multilevel regression models show that, due to ‘tougher’ immigration positions taken by centre-right parties in government, immigration-welcoming citizens become more distrustful, whereas the already high level of distrust among immigration-sceptical citizens remains largely unchanged. Furthermore, political distrust is found to become less relevant an individual-level driver of voters' propensity to support FRPP because political distrust levels become more similar across the immigration policy space in the citizenry yet without making FRPPs lose voters because of it.

Thus, this study tells a cautionary tale of how tougher mainstream party immigration position-taking can have unanticipated and undesirable societal repercussions, namely higher overall levels of public political distrust alongside a sustained FRPP vote. Moreover, contrary to much existing research highlighting political distrust as a universal precursor of far-right voting, this study suggests that the relevance of the distrust-related FRPP vote is not unequivocally given, but ultimately contingent on the causes of political distrust: citizens' instrumental evaluations of how mainstream parties handle the immigration issues relative to their own policy preferences.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The following section presents the theoretical framework based on a synthesis of relevant literatures to underpin the proposed arguments and expectations of this study. The third section discusses the data and methods leveraged to test the hypotheses. Thereafter, the fourth section presents the empirical results, and the final section concludes by noting the implications of this study for our understanding of immigration policy and politics, and its contributions to the existing literatures on party competition, citizens' democratic support and far-right voting.

Theoretical framework

Theorizing the link between mainstream party position-taking, immigration preferences and political (dis)trust

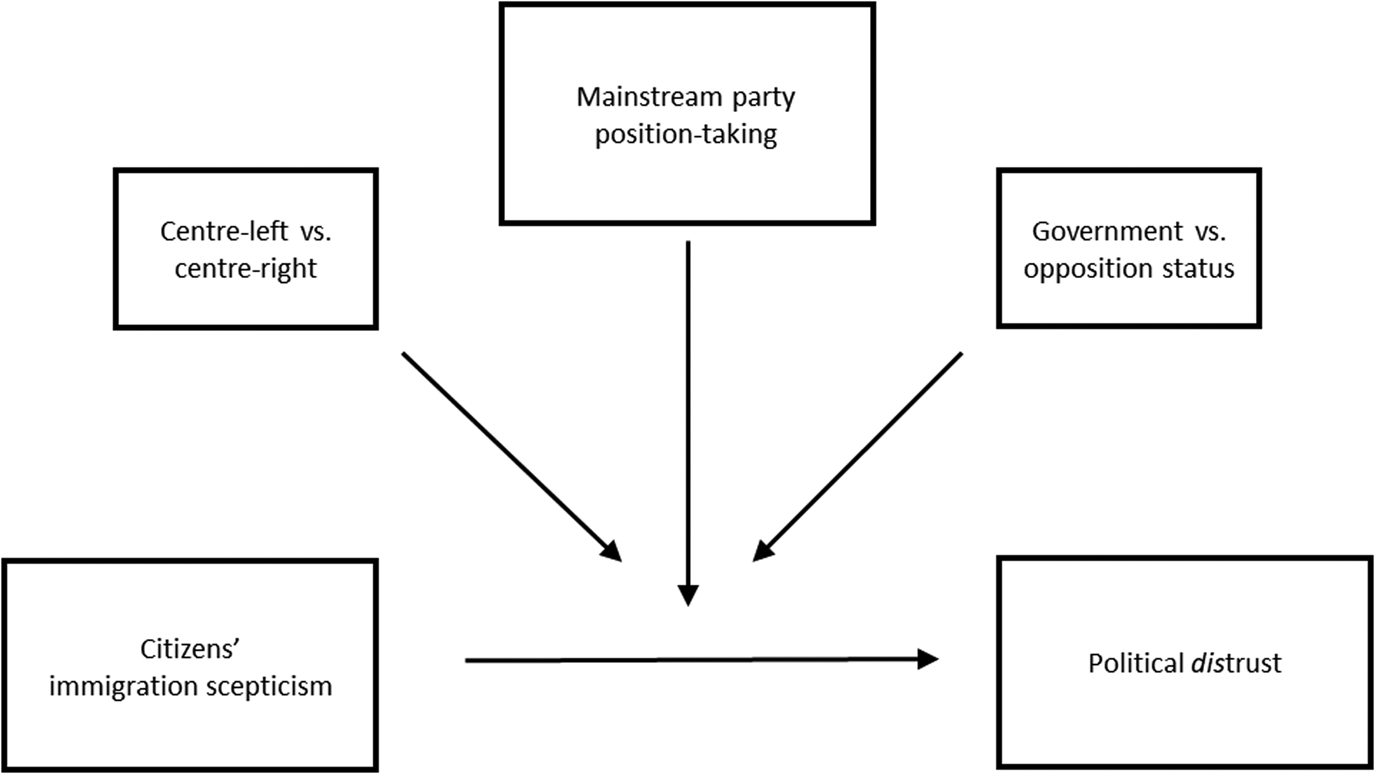

The theoretical framework of the present study synthesizes the academic literatures on immigration-related political trust and spatial theory to theorize the effect of mainstream party position-taking. Figure 1 illustrates the different components of the proposed argument, which will be further explicated in the following paragraphs. In short, the argument draws first on the literature on immigration-related political trust (e.g. McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017) to derive the baseline expectation that immigration scepticism increases political distrust (the horizontal link). Drawing on spatial theory (e.g. Downs Reference Downs1957; Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1997), this link is secondly envisioned as being shaped by the immigration-related position-taking of mainstream parties (the vertical link). Thirdly, this party effect itself is considered contingent on specific party traits, namely whether mainstream parties are centre-left or centre-right and whether they are in government or opposition (the diagonal links).

Figure 1. Graphical Representation of the Theoretical Argument.

The positive impact of immigration-sceptical attitudes on political distrust (the horizontal link in Figure 1) is a robust finding of extant research in Western democracies. More specifically, studies suggest that citizens' negative sentiments towards immigration and multiculturalism are pertinent sources of political distrust (Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017). Conceptually, political trust refers to citizens' generalized perceptions of whether political elites and the wider political system fulfil legitimate functions in the daily conduct of politics (Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000; Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990). Citizens who distrust their political representatives and the institutions in which they operate, such as governments, parliaments and parties, generally perceive elites to conduct politics without following key moral qualities, such as honesty, reliability, fairness and responsiveness to society's needs (Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990: 358). Whereas political trust is typically ‘accompanied by a sense of confidence, security, perhaps even well-being, and … loyalty toward the trusted’, distrust ‘carries negative affective orientations such as suspicion, antipathy and resentment’ (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings2021: 1177).

Arguably, the link between immigration attitudes and feelings of political (dis)trust arises from citizens' dissatisfaction with past and ongoing immigration inflows and the increasing ethnic diversification of Western societies (Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017). Immigration-sceptical citizens tend to blame political elites and the institutions in which they operate to ‘have sold out the public by failing to protect the national community from the potentially disruptive and divisive force of immigration’ (McLaren Reference McLaren2012: 205). The baseline expectation (the horizontal link in Figure 1) following from this literature is thus that immigration-sceptical citizens should display higher levels of political distrust than immigration-welcoming citizens.

Turning to the vertical link in Figure 1, the next theoretical step engages with the question of whether the immigration-(dis)trust link at the citizen level is sensitive to party position-taking on the immigration issue. Spatial theory is a useful starting point to understand this intuition. Essentially, spatial theory assumes that citizens constantly evaluate the proximity between their own policy positions and those of political parties in order to form political attitudes and assess different behavioural options (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2020; Downs Reference Downs1957; Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1997; Otjes and de Wardt Reference Otjes and de Wardt2020; Stecker and Tausendpfund Reference Stecker and Tausendpfund2016). Following from this logic, closer proximity to parties is not only assumed to increase the likelihood of voting for proximate parties (Downs Reference Downs1957; Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1997) but also the likelihood of assessing the core institutions of democracy in more favourable terms (Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990; Stecker and Tausendpfund Reference Stecker and Tausendpfund2016). Recent research suggests that the spatial logic in relation to salient ‘second-order’ issue dimensions, such as immigration, is particularly well suited to explain citizens' confidence in the political system (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2020; Stecker and Tausendpfund Reference Stecker and Tausendpfund2016).

Thus, by bridging the literatures on immigration-related distrust with spatial theory, the connection between citizens' immigration-related political (dis)trust evaluations and parties' position-taking on the immigration issue can be conceptualized as follows: if the link between citizens' immigration-sceptical attitudes and political distrust originates from citizens' assessment of how parties have managed mass immigration in the past, then parties might have leverage to rectify this bias through position-taking in the present. More concretely, the question to be answered is: do political parties' positions on the immigration issue shape the deviating (dis)trust levels of immigration-sceptical and immigration-welcoming citizens potentially to rectify the (dis)trust imbalance between those citizen groups?

To theorize this causal mechanism properly, it is instrumental to clarify the underlying motivational assumptions due to which citizens develop feelings of (dis)trust. The present study builds on the assumption that the citizen-level link between immigration preferences and political (dis)trust is largely based on outcome-based rather than process-based considerations. Process-based considerations refer to the question of whether citizens feel that their interests are at all given a voice in the process of parliamentary representation via any represented party, regardless of policy outcomes (e.g. Dunn Reference Dunn2015).

By contrast, outcome-based trust is essentially an instrumental consideration relating to the policy outcomes that the process of political representation engenders. This conception can draw on a long tradition of research on election outcomes showing that individuals' political trust and democratic satisfaction suffers considerably after having voted for losing parties (e.g. Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2005; Anderson and LoTempio Reference Anderson and LoTempio2002). More recently, research on referendums suggests similarly that instrumental considerations tied to preferred policy outcomes go a long way in explaining citizens' support for referendums on specific policy proposals (Werner Reference Werner2020; Werner and Jacobs Reference Werner and Jacobs2022). In fact, the already referenced literature on immigration-related political (dis)trust also puts policy outcomes implicitly centre-stage by arguing that political distrust hinges on how citizens assess the (in)ability of political elites to avert or moderate large-scale immigration and ethnic diversification as a policy outcome (McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017).

Presuming that instrumental considerations underpin the development of political (dis)trust leads to the expectation that different party traits are likely to matter for the link between immigration-scepticism and political distrust (the diagonal links in Figure 1). First, it can be expected that mainstream party position-taking is of particular importance. Given mainstream parties' central role in the party system and government businesses, immigration critics are especially likely to view mainstream parties ‘as part of the system, and thus as part of the problem’ (Belanger and Nadeau Reference Belanger and Nadeau2005: 137; Hernández Reference Hernández2018: 460), because in their eyes those parties are responsible for too lax immigration policies that have paved the way for the multicultural transformation of society. It is therefore plausible to assume that large parts of citizens' political (dis)trust are attributed to mainstream parties. In turn, feelings of political distrust should hinge on the distance between citizens' own immigration policy preference and the position-taking of mainstream parties.

More concretely, mainstream parties might be able to restore the trust of immigration-sceptical citizens in the political system by credibly committing to more restrictive immigration and integration policies, such as tightening up asylum laws and citizenship acquisition rules, or requiring immigrant minorities to assimilate more strongly to the host society's cultural norms. However, if we take the main propositions of spatial theory literally, such a party move could also adversely affect political trust levels on the immigration-welcoming side of the spectrum. That is, more restrictive mainstream party positions on immigration may turn immigration-welcoming citizens more strongly into ‘policy losers’ and thereby lead to an erosion of political trust levels among citizens who advocate more liberal immigration policies. These considerations lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The link between citizens' immigration scepticism and political distrust becomes weaker the more restrictive the immigration policy positions of mainstream parties are.

Second, it is plausible to expect differential effects depending on whether the mainstream party is centre-left or centre-right. Centre-right parties should be better situated than centre-left parties to credibly commit to restrictive immigration and integration policies given their ideological ‘playing field’ located right of the political centre, which makes them considerably tougher than the mainstream left in terms of immigration policy (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2021; Bale Reference Bale2008). Centre-left parties, by contrast, generally locate in the more moderate realms of the immigration policy spectrum. While centre-left parties might thus generally not be in a position to take credible and ‘tough enough’ positions in the policy space, centre-right parties may be better able to frustrate immigration-welcoming citizens and/or please citizens with firm anti-immigrant viewpoints. Presuming that citizens develop their political (dis)trust levels based on expected policy outcomes, tougher positions taken by centre-right parties, but not by centre-left parties, may thus jeopardize the former group of citizens' political trust while restoring the level of trust of the latter group.

Hypothesis 2: The link between citizens' immigration scepticism and political distrust becomes weaker the more restrictive the immigration policy positions of centre-right mainstream parties are.

Lastly, if instrumental considerations were underlying citizens' political (dis)trust evaluations, it is furthermore plausible that centre-right party position-taking on the immigration issue has the strongest impact on political (dis)trust when in government. Arguably, being in government rather than in opposition will provide parties with the greatest leverage over policy outcomes given their improved command over parliamentary majorities and government portfolios. Citizens, in turn, who develop political trust levels based on outcome-based evaluations, should respond most strongly to the immigration-related position-taking of centre-right parties when in government.

Hypothesis 3: The link between citizens' immigration scepticism and political distrust becomes weaker the more restrictive the immigration policy positions of centre-right mainstream parties are, contingent on those parties' government participation.

Does the trust-shaping effect of mainstream party position-taking matter for far-right voting?

Alongside this article's interest in whether citizens' political trust levels are sensitive to the immigration policy positions taken by mainstream parties, it also seeks to understand the consequence of this interaction for citizens' likelihood to cast an FRPP vote. Existing research on far-right voting can be broadly categorized as highlighting two voter motives: policy and protest motives (e.g. Cohen Reference Cohen2020; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008). Whereas policy motives relate mainly to immigration and integration issues, protest motives are considered to be not in favour of a particular political party or candidate, but rather against the ruling political elite and the institutions in which the daily conduct of mainstream politics takes place. Plausibly, this form of anti-elitism is encoded in the concept of political distrust, wherefore scholars of far-right voting behaviour commonly equate protest motives with a lack of political trust (see Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018: 356; Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2001: 233).

However, empirical findings reported in the literature suggest a rather nuanced picture of how protest motives relate to voters' electoral support for FRPPs. Studies suggest that protest motives ought not to be viewed as completely decoupled from political preferences (Cohen Reference Cohen2020; Hernández Reference Hernández2018). As Enrique Hernández (Reference Hernández2018: 461) puts it, ‘the process by which discontent relates to party choices should not only be influenced by citizens’ desire to protest, but also by what citizens want to protest about’. This sits well with this study's assumption of citizens' political (dis)trust evaluations being based on policy outcome-based considerations.

Hence, the present study proposes that that the trust-shaping effect of mainstream party position-taking extends to the relevance of political distrust as a precursor of far-right voting. If, as argued in the previous subsection, the adoption of tougher party stances makes previously distrustful immigration-sceptical citizens more trustful and/or conversely prompts previously more trustful immigration-welcoming citizens to become more distrustful, this implies a possible alteration of the trust imbalance across the immigration policy spectrum. That is, due to the two citizen groups' antagonistic moves in response to mainstream party position-taking, immigration-sceptical and immigration-welcoming citizens might become more similar, converge, or switch completely with regard to their political (dis)trust levels. However, the increased political distrust among immigration-welcoming citizens resulting from their frustration with what they see as too restrictive immigration positions taken by mainstream actors is unlikely to translate into support for the most anti-immigration voices in the political system, namely FRPPs. Put differently, political distrust will not unequivocally increase the likelihood of far-right voting, but only if it is rooted in voters' frustration with too liberal, rather than too restrictive, immigration positions of mainstream elite actors.

Consequently, the distrust among immigration-sceptical voters, who are a key segment for FRPP mobilization, may no longer exhibit as strong an association with far-right party support because immigration-welcoming citizens, who tend to be opposed to the anti-immigration platform of FRPPs, have now more similar, or even more severe, levels of political distrust.

Since the trust-shaping effect of mainstream party positions can be expected to be augmented for centre-right parties and when in government (see H3 and H4), the relevance of these intervening factors can also be expected to matter by extension for the phenomenon of far-right voting.

Hypothesis 4: The link between citizens' political distrust and FRPP support becomes weaker the more restrictive the immigration policy positions of centre-right mainstream parties are, contingent on those parties' government participation.

Data and methods

Pursuing these hypotheses requires linking attitudinal individual-level data on citizens to contextual-level data on party positions on the immigration issue across Western European countries. The present article seeks to meet this requirement by leveraging a joined dataset of party-level expert survey data from the CHES project (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly and Bakker2022) and individual-level survey data from the ESS (European Social Survey 2020). This dataset covers 14 Western European countries and 49 country-survey waves in 2006 (ESS wave 3), 2010 (ESS wave 5), 2014 (ESS wave 7) and 2018 (ESS wave 9), for which individual-level and contextual-level indicators were available in all cases. Table 1 provides an overview of selected countries and CHES/ESS survey waves.

Table 1. Country Selection, Corresponding CHES/ESS Waves, and Selected Parties

Note: Please see Table A4 in Supplementary Material A for a list of the parties' full names.

Main variables

Six main variables are at the centre of the analysis. At the individual level, these are citizens' political trust, whether or not they voted for a FRPP, and their viewpoints on immigration policy. At the party level, centre-right and centre-left parties' position-taking on the immigration issue are distinguished, as well as those parties' government participation. For better comprehensibility, party-level variables are from now on indicated in CAPITAL LETTERS.

Political trust is both a dependent variable in its own right, and an explanatory variable of far-right voting. Three ESS survey items measure respondents' trust in politicians, parties and national parliaments in a consistent manner across time and countries by asking, ‘Using this card, please tell me on a score of 0–10 how much you personally trust each of the institutions I read out … politicians/parties/[country’]s parliament.’ Higher values on these scales represent higher levels of trust in the respective institutions/actors. Since the three items have a high internal validity (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91), they were combined in a single variable by standardizing individuals' responses between values of 0 and 1 (by dividing values by 10) and then averaging across the three items to obtain a generalized single indicator of citizens' political trust. Please note that this indicator is likely to blur some of the subtle differences between lack of trust, mistrust and distrust (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings2021). Nevertheless, the political trust measures provided by the ESS can be taken as rather granular indicators that range from trust at one end to distrust at the other, with mistrust in the middle (Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018: 51). Moreover, as the ESS provides this indicator across time and several Western European countries in a consistent manner, it is clearly the preferred source of data for the purpose of testing this paper's hypotheses.

FRPP vote is the second dependent variable in this study, measuring whether respondents have voted for an FRPP in the most recent election ( = 1) or not ( = 0) (variable group ‘Party voted for in last general election’). FRPPs are identified according to the following procedure. First, the party FAMILY variable in the CHES dataset is leveraged by considering all those parties labelled as ‘radical right’. Since the ESS indicates additional potential FRPPs, additional parties are considered following existing scholarship (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2021; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2022; McLaren Reference McLaren2012; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018) and own knowledge. Table 1 indicates all the parties considered as FRPPs in this study.

A third key individual-level variable is citizens' viewpoints on immigration policy. Three ESS itemsFootnote 1 are leveraged that tap into the economic and cultural-identity consequences of immigration and multiculturalism as perceived by respondents. Responses are coded on scales from 0 to 10, which were recoded/reversed so that higher values indicate more immigration-scepticism. The three items have a high internal validity (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86), such that a single indicator is created by standardizing values between 0 and 1 (by dividing values by 10) before averaging across individual responses as suggested by Lauren McLaren (Reference McLaren2012).

For assessing mainstream parties' immigration policy positions, the data provided by the CHES project is utilized. Of specific interest is the position-taking of mainstream centre-right and centre-left parties. Parties are considered as centre-left if the CHES party FAMILY variable codes them as ‘Socialist’, although recently formed parties are excluded.Footnote 2 In defining ‘centre-right’ parties, this study follows Leila Hadj Abdou et al. (Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2022: 331), who conceptualize parties in that category as a ‘broad church’ composed of more than one party family, ‘namely, conservative, Christian democrat and (some, though not all) liberal parties’.

In order to determine mainstream parties' positions on the immigration issue, three CHES items are leveraged, which are available in a consistent manner across the 14 countries under study for the years 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2019: IMMIGRATE_POLICY,Footnote 3 MULTICULTURALISMFootnote 4 and ETHNIC_MINORITIES.Footnote 5 In both groups of mainstream parties, these three items have a high internal validity agreement with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89. Thus, an ANTI-IMMIGRATION POSITION index is created for both centre-left and centre-right parties in the following manner. First, the three scales are averaged into a single policy dimension for each party per year. Second, given that there may be more than one centre-right or centre-left party in a country-year (see Table 1), for both party groups a summary scale is constructed, in which each party position is weighted by the party's seat share relative to the parliamentary seats of all parties in that party group.Footnote 6

Figure 2 provides insights into the distribution of the ANTI-IMMIGRATION index for centre-right (top panel) and centre-left parties (bottom panel). As can be see, centre-right positions tend to locate to the right of centre between values of 3.2 and 8.1 (mean = 6.6), but without taking extreme positions greater than 8, which makes them distinguishable from the extreme positions of FRPPs. By contrast, centre-left positions locate notably more to the left by taking values between 2.4 and 6.7 (mean = 4.1). At the same time, positions differ significantly not only between the two party groups, but also within, given that each group's variance spans roughly half of the ideological spectrum.

Figure 2. Mainstream Parties' Immigration Policy Positions.

Eventually, the theoretical framework and therefore the analysis takes into consideration the GOVERNMENT involvement of mainstream parties. Based on information provided by the CHES dataset,Footnote 7 the analysis distinguishes whether parties in a given year were in government (= 1) or not (= 0).

Control variables

The analysis further controls for variables that could conflate the relationships between the independent and dependent variables, namely well-known individual-level variables of demography, social capital and political orientations (e.g. Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Marien and Hooghe Reference Marien and Hooghe2011; McLaren Reference McLaren2012). Sociodemographic controls include gender,Footnote 8 ageFootnote 9 and age squared in years, educational attainmentFootnote 10 in years of full-time education completed, and whether or not citizens are unemployed.Footnote 11 Citizens' social capital is assessed by citizens' attendance at religious services,Footnote 12 by their frequency of meeting other people (social contactsFootnote 13), by whether or not they are members in a labour unionFootnote 14 and by whether they live in a partnership (married or non-married) with another person.Footnote 15 Political orientation controls extend to political interest, party closeness and left–right ideological self-placement. Political interest is measured on a four-point Likert-scale.Footnote 16 Individuals' psychological closeness to a political party measures whether respondents feel closeFootnote 17 to a party and how strongFootnote 18 this feeling of closeness is, ranging from 0 (‘no party closeness’) to 4 (‘strongest party closeness’). Citizens' ideological left–right placementFootnote 19 is measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating more rightist positions.

Lastly, the analysis further accounts for macro-level influences of political context. This heeds the findings of extant research suggesting that FRPPs' parliamentary seat share and involvement in government coalitions can have crucial repercussions for public political trust and the electoral support of FRPPs (Cohen Reference Cohen2020; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020; Muis et al. Reference Muis, Brils and Gaidytė2022). Information on FRPPs' parliamentary seat shares and government involvementFootnote 20 is taken from the CHES dataset.

Table A1 in Supplementary Material A provides descriptive statistics for all variables entered into the models presented in the results section.

Statistical models

Given the data structure and research questions at hand, which are interested in how contextual variation of party policy positions at the country-year level interacts with individual-level variables to shape political trust and far-right voting, multilevel regression models are the preferred modelling choice (Gelman and Hill Reference Gelman and Hill2007: chapters 11 and 14). More precisely, to explain citizens' political trust, which is a continuous variable, linear multilevel regression models are estimated; to model the binary decision to cast a vote for an FRPP, logit multilevel regression models are relied upon.

In the dataset at hand, 78,831 individual-level citizen observations are clustered in 49 country-survey waves. Party-level variables vary in this dataset at the level of country-survey waves. More concretely, indicators for mainstream party position-taking and parties' government participation vary not only across countries, but also within countries over time/survey waves. In other words, there are 49 distinct values for these contextual-level variables, that is, one value per country-survey wave. Following the suggestions of Alexander Schmidt-Catran and Malcolm Fairbrother (Reference Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother2016), it would be erroneous to model this variation in a multilevel model specifying the country level (i.e. the 14 countries) as the second level because this would treat the party-level data implicitly as individual-level data, thereby ‘inflating the degrees of freedom and deflating the SEs’ (Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother Reference Schmidt-Catran and Fairbrother2016: 25). Therefore, the multilevel model specifications in the succeeding regression analyses treat individual-level citizen observations (level 1) as clustered in 49 country-survey waves (level 2).Footnote 21

For both linear and logit regression models, the first analytical step is based on the estimation of random-intercepts models that consider level-1 and level-2 predictors, but without any interaction effects. In succeeding analytical steps, this model is extended by two-way and three-way interaction effects between predictors at level-2 (mainstream party positions on immigration and those parties' government–opposition statuses) and level-1 (citizens' immigration-scepticism and political trust) including random coefficients for the level-1 predictor variables.

Prior to these estimations, all individual-level and control variables that are based on Likert scales were standardized between values of 0 and 1. Moreover, all continuously coded variables were centred following the suggestions of Craig Enders and Davood Tofighi (Reference Enders and Tofighi2007). Thus, level-2 variables are grand mean-centred and level-1 covariates are within-cluster mean-centred.

Results

Supplementary Material A provides more empirical materials adding to this ‘Results’ section, while Supplementary Materials B and C present robustness checks.

Mainstream party positions on immigration and political trust

Table 2 presents an extract of the estimates of four multilevel linear models regressing the political trust variable on the immigration policy preferences of voters, the position-taking of centre-left or centre-right parties and those parties' government–opposition statuses while controlling for potentially confounding factors as outlined in the previous section. For illustration purposes, only the coefficients for the main variables are displayed in the table while full models are provided in Table A2 of Supplementary Material A.

Table 2. Multilevel Linear Regression Models Explaining Political Trust

Notes: CLP = centre-left party; CRP = centre-right party. Multilevel linear regression mixed effects estimates; standard errors reported in parentheses; post-stratification weights applied.

a Centred at global mean.

b Centred at within-cluster mean; estimates for control variables not displayed; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results from a baseline model without interaction effects (Model 1) suggests that citizens' viewpoints on immigration policy are a central determinant of their political trust levels, which substantiates previous key findings in the literature (Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017) and thus confirms the baseline expectation. More specifically, Model 1 suggests that, when a citizen's anti-immigration position increases by one unit (from the lowest observed value to the highest in a country), the political trust indicator decreases by 0.281 units (on a scale ranging from 0 to 1).

Interestingly, the baseline model further suggests that the country-year-level variable for centre-left-party position-taking on the immigration issue exerts a statistically significant positive effect on the dependent variable, whereas centre-right-party position-taking exerts a negative effect. However, the significance of the former of those relationships does not prove to be robust in alternative model specification (see particularly Table B6.1 in Supplementary Material B).

Additional models are estimated (Models 2, 3 and 4) that include cross-level interactions between citizens' immigration preferences, mainstream parties' immigration policy positions and the government–opposition status of centre-right parties in order to examine whether and how these variables shape each other's effects on political (dis)trust.

In a first step, Models 2 and 3 probe H1 and H2 by extending the baseline model by the interaction between citizens' and parties' immigration preferences. The interaction term in Model 2 suggests that the position-taking of centre-left parties has no notable moderating relevance for the impact of citizens' immigration-scepticism on political trust. By contrast, the interaction term in Model 3 suggests that the position-taking of centre-right parties matters a great deal more as a moderating factor. That is, the positive and statistically significant coefficient suggests that the negative effect of citizens' immigration-scepticism on political trust becomes smaller as centre-right parties take more restrictive stances on the immigration issue. This speaks more in favour of H2 than H1.

However, H3 posits that the negative impact of immigration-scepticism on political trust is further moderated by the government–opposition status of centre-right parties. In order to test for this additional condition in the data, Model 4 extends the baseline model by the three-way interaction between citizens' anti-immigration views, centre-right party position-taking, and those parties' government–opposition status (Model 5 in Table A2 in Supplementary Material A replicates the three-way interaction for centre-left parties). The results of Model 4 for centre-right parties are visualized in Figure 3 in the form of marginal effects estimations. That is, the plots visualize the estimated effects of a one-unit change in the restrictiveness of citizens' immigration policy preferences on their political trust levels depending on centre-right party position-taking on the immigration issue (Figure A1 in Supplementary Material A replicates those estimations for centre-left parties).

Figure 3. Marginal Effects of Citizens' Immigration-Scepticism on Public Political Trust.

Note: Plots are based on Model 4 in Table 2.

The left-hand plot suggests that, when centre-right parties are in opposition, the negative impact of immigration-scepticism on political trust remains largely constant, regardless of how restrictive the position-taking of those parties is. However, the right hand-plot suggests that the moderating effect of centre-right parties' position-taking indicated by Model 3 appears to be mainly driven by those parties' government status. More concretely, the plot shows that the negative effect of immigration-scepticism on political trust becomes notably smaller as centre-right parties in government take more restrictive immigration positions. This finding corroborates H3 rather than H2 or H1. In other words, the position-taking effect depends on centre-right parties that are in government.

In order to understand better whether the position-taking of centre-right government parties shape the political (dis)trust levels of immigration-welcoming and immigration-sceptical citizens in a different manner, Figure 4 visualizes additional marginal effects estimations based on Model 4. Differently to Figure 3, this plot treats citizens' anti-immigration positions as the moderator, thus showing the marginal effects of the position-taking of centre-right government parties on citizens' political trust depending on the immigration policy preferences of those citizens. As can be seen, the estimates suggest that the impact of more restrictive party positions shrinks as citizens' policy preferences become more anti-immigration. On the immigration-friendly end, political trust levels deteriorate most strongly. However, on the immigration-sceptical end of the citizen spectrum, the party effect is smallest and fails to reach levels of statistical significance.

Figure 4. Marginal Effects of Centre-Right Parties' Immigration Position-Taking on Public Political Trust.

Note: Plot is based on Model 4 in Table 2.

Please note that these findings do not change either in alternative model specifications (see Supplementary Material B) or in a replication of the marginal effects estimations following the recommendations of Jens Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) (see Supplementary Material C).

Mainstream party positions on immigration and the impact of political trust on FRPP voting

Table 3 reports the results of four multilevel logit models intended to model the phenomenon of far-right voting (full models are presented in Table A3 of Supplementary material A). Model 1 shows the results from an estimation without interactions, which reiterates well-known empirical patterns, such as that the decision to cast an FRPP vote is strongly influenced by citizens' viewpoints on immigration policy and by how much trust they place in the political system.

Table 3. Multilevel Logit Models Explaining FRPP Voting

Notes: CLP = centre-left party; CRP = centre-right party. Multilevel logit regression mixed effects estimates; standard errors reported in parentheses; post-stratification weights applied.

a Centred at global mean.

b Centred at within-cluster mean; estimates for control variables not displayed; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

However, when extending this model by the interactions between political trust and party position-taking (Models 2 and 3), it turns out that the relevance of political distrust as a determinant of far-right voting should not be considered in isolation from the policy positions that mainstream parties take on the immigration issue. In particular centre-right party position-taking (Model 3) appears to weaken the association between political distrust and far-right voting.

In order to understand to what extent this empirical pattern depends on centre-right parties' government participation as posited by H4, Model 4 includes the three-way interaction between political trust, centre-right party position-taking on immigration and those parties' government versus opposition status (Model 5 in Table A3 in Supplementary Material A replicates the three-way interaction for centre-left parties). Based on Model 4, Figure 5 visualizes the relationship between far-right voting and political (dis)trust in the form of predicted probabilities plots depending on whether centre-right mainstream parties are in government and whether they take more liberal or more restrictive stances on the immigration issue (Figure A2 in Supplementary Material A replicates those estimations for centre-left parties).Footnote 22 As can be seen, the most notable difference between more restrictive and more liberal immigration positions taken by centre-right parties materializes when those parties are in government. When centre-right government parties (the right-hand plot) take more liberal immigration positions, political distrust has a notable positive impact on the propensity to vote for FRPPs. However, not only is this impact substantially smaller when those parties take more restrictive immigration positions, as indicated by a notably flattened slope, but the two slopes are also clearly distinguishable in terms of their confidence intervals. Conversely, although the difference in the steepness of the slopes is still visible in the left-hand plot, the large overlap between the confidence intervals provides less confidence in the relevance of these position-taking dynamics when centre-right parties are in opposition. Taken together, these findings thus lend support for H4.

Figure 5. Political Trust and the Likelihood of FRPP Voting.

Note: Plots are based on Model 4 in Table 3.

Alternative model specifications showing the robustness of the model estimations are provided in Supplementary Material B.

Conclusion

The question of whether mainstream parties should take a ‘tougher’ immigration policy position is at the heart of contemporary public and academic political discourses. As political conflict over immigration issues is widely considered to feed into the erosion of public political trust and the electoral success of FRPPs across Western European democracies, the question arises whether such party position-taking can restore the trust of immigration-sceptical voters in the political system and thereby curb the overall electoral support for FRPPs.

The present study speaks to these debates by providing the first systematic analysis of whether and how mainstream party positions on the immigration issue matter for citizens' political trust and, by extension, the relevance of political trust as a precursor of FRPP voting. Three central findings stand out.

First, citizens' immigration scepticism becomes less strongly a determinant of political distrust when mainstream parties adopt more restrictive immigration positions. However, only the immigration policy positions adopted by centre-right parties are found to have this moderating effect, while there is little evidence that those of centre-left parties have an effect. In addition, the position-taking effect of centre-right parties is further conditional on their government participation.

Second, this trust-shaping effect works mainly through a deterioration of the political trust levels of citizens on the immigration-welcoming end of the policy spectrum, whereas the already low level of political trust of citizens with firm anti-immigration viewpoints remains largely unchanged. This suggests that, although the trust-(im)balance across the immigration policy spectrum changes, the overall level of public political distrust worsens.

Third, as centre-right government parties go tougher on the immigration issue, political distrust becomes less relevant a driver of the FRPP vote. This is likely a consequence of the trust-shaping effect of such position-taking across the immigration policy spectrum. While immigration-welcoming citizens become more like immigration-sceptical citizens in terms of their (dis)trust levels (i.e. they become less trustful), they are likely to remain opposed to the anti-immigration platforms of FRPPs out of policy considerations. Yet there is little evidence suggesting that immigration-sceptical voters are discouraged from supporting FRPPs due to restored political trust levels, which is why the electoral wind in FRPPs' sails is likely to remain steady.

Viewed in conjunction, these findings are therefore highly relevant as they suggest that the decision of centre-right parties to be tougher on immigration in order to curb FRPP support can have serious unanticipated and undesirable repercussions in relation to a key currency of democracy, namely public political trust, while FRPPs continue to garner significant vote shares. As such, the uncovering of these empirical patterns is of further importance as they make relevant contributions to several political science literatures.

The first two main findings add to the literature on the link between political trust and immigration politics, which has established that a pertinent source of political distrust is citizens' immigration grievances (Berg and Hjerm Reference Berg and Hjerm2010; McLaren Reference McLaren2012, Reference McLaren2017). While this literature has convincingly argued and empirically shown that a substantial share of citizens' political distrust originates from the dissatisfaction of immigration sceptics with how mainstream political actors have managed mass immigration and the multicultural transformation of Western societies in the past, little is known about whether this link is actually amenable to the behaviour of mainstream political actors in the present. This study narrows this gap by showing that the immigration policy positions adopted by centre-right mainstream parties in government is a crucial contextual factor to consider. The relative importance of the government status of centre-right parties in this relationship emphasizes further the relevance of citizens' policy outcome-based consideration for their (dis)trust evaluations. However, as the position-taking effect plays out mainly as a trust-deteriorating effect on the immigration-friendly end of the political spectrum, one could infer that political trust is a democratic resource that is more easily lost than restored. If true, this would raise the long-term stakes of such party position-taking for the wider democratic system even higher.

Moreover, the third finding improves our knowledge of the conditions under which political distrust is a driver of FRPP support. Existing research commonly equates distrust-related electoral support for FRPPs with protest voting, which is assumed to be distinct from policy-based voting motives (Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink2020; Hernández Reference Hernández2018; Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2001). However, the present study suggests that policy outcome-based motives are not completely separable but in fact an important ingredient of the distrust-based FRPP vote. That is, citizens' instrumental evaluations of how the position-taking of centre-right parties relates to their own policy preferences – that is, whether they consider the position-taking to be too liberal or too restrictive – appears to determine whether a high political distrust level increases the likelihood of supporting FRPPs. This provides a plausible explanation for why political distrust is commonly reported to matter more in some time and country contexts than in others (Norris Reference Norris2005; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018). By highlighting the relevance of mainstream party position-taking on immigration, this study thus adds further to a burgeoning body of research suggesting that the composition of the group of FRPP supporters hinges to a considerable degree on contextual factors (Cohen Reference Cohen2020; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020; Muis et al. Reference Muis, Brils and Gaidytė2022).

Lastly, all three findings also contribute to the literature on the consequences of mainstream party position-taking on immigration. This area of research has mostly focused on the unconditional consequences for citizens' propensity to vote for FRPPs, suggesting overall that mainstream parties' attempts to go ‘tougher’ on immigration-related issue dimensions do not serve the goal to recapture renegade voters who have defected to support FRPPs (e.g. Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2021; Dahlström and Sundell Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012; Down and Han Reference Down and Han2020; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2022). However, a full examination of the consequences that mainstream party positions on immigration can have for democratic life and politics requires political scientists to look beyond immediate impacts on voting behaviour. That is, it is equally important to consider their potential consequences for fundamental democratic norms and attitudes in the citizenry. Plausibly, as many of those attitudes are known to exert an influence on voting behaviour as causally more distant factors (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell1960: 24–37), altering them could effectively ‘preempt voting for a radical-right party’ (Williams and Hunger Reference Williams and Hunger2022). The present study addresses this gap by putting its analytical spotlight on political trust, a key democratic resource commonly considered to affect far-right voting.

For all its contributions to existing literatures, this study also opens up new avenues for future research. Based on the findings uncovered here, one might conjecture that more restrictive centre-right positions on immigration have overall more undesirable than desirable societal consequences. Yet before making such a general conclusion, political scientists ought to consider other potentially important political consequences as well. In particular the trust-shaping effect of centre-right government parties' positions warrants further research in that respect. The present study has focused on how the trust-shaping effect matters for far-right voting. However, political trust is known to have several other important repercussions for democratic life, such as electoral turnout, citizens' obedience to the state's authoritative decision-making power and their acceptance of violence as a legitimate form of political action (Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Marien and Hooghe Reference Marien and Hooghe2011; Stoker and Evans Reference Stoker, Evans, Elstub and Escobar2019). These would be important areas where succeeding research could take this research agenda forwards.

Furthermore, what are the repercussions of the political trust-shaping effect on the immigration-welcoming side of the political spectrum? This study finds that political trust levels among immigration-welcoming citizens crumble in response to more restrictive immigration policy positions taken by centre-right government parties. Since political trust is also known to feed into voting for far-left populist parties (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018), this could enable these parties to siphon off voters from centre-left mainstream parties. In other words, whether knowingly or not, by going tougher on the immigration issue centre-right parties in government could weaken the electoral outlook of centre-left mainstream parties rather than that of FRPPs (for a similar argument on the position-taking of centre-left parties see Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2024.6.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2021 ECPR Joint Sessions in the workshop ‘Substantive Representation of Marginalized Groups: Re-Conceptualizing, Measurement, and Implications for Representative Democracy’ and in the Comparative Politics research seminar at the University of Bamberg. I would like to thank in particular John Kenny and three anonymous referees for valuable comments and feedback and the participants of the mentioned audiences.