Tens of thousands of new publications now appear each year on “emotion regulation.” However, despite the very high level of enthusiasm for this topic across psychology and related fields, there remains considerable confusion about what emotion regulation actually is (and is not). In this chapter, we provide an overview of this rapidly growing field, with particular attention to concepts and findings that may be of special relevance to scholars interested in the links between emotion regulation and parenting. Because any discussion of emotion regulation depends upon one’s assumptions about emotion, we begin by asking: What is an emotion?

2.1 Emotion and Related Constructs

Emotions come in many different shapes and sizes (Suri & Gross, Reference Suri and Gross2022). Sometimes emotions are pleasant; other times they are unpleasant. Sometimes they are very mild, so that we can scarcely tell we’re having an emotion. At other times, emotions are so intense that we’re scarcely aware of anything else. Sometimes it’s clear what label to apply to our emotions (e.g. anger, sadness, amusement). Other times, our emotions are hard to define. Given this remarkable diversity, affective scientists have struggled to define the core features of emotion.

2.1.1 Core Features of Emotion

According to the “modal model” of emotion (Figure 2.1), emotions may be seen as arising through a cycle that consists of four elements: (1) a situation (either experienced or imagined); (2) attention that determines which aspects of the situation are perceived; (3) evaluation or appraisal of the situation in light of one’s currently active goals; and (4) a response to the situation, which may include changes in subjective experience, physiology, and facial or other behaviors (Gross, Reference Gross2015).

Figure 2.1 Modal model of emotions

Note. Emotions commonly arise in the context of (1) a situation that is either experienced or imagined, (2) attention that influences which aspects of the situation are perceived, (3) an evaluation or appraisal of the situation, and (4) a response to the situation that alters the situation that gave rise to the emotion in the first place.

Consider an exhausted parent wheeling a shopping cart through a grocery store with a toddler in tow. The toddler can’t make up their mind as to whether they want to walk or sit in the shopping cart. So no sooner are they safely installed in the cart do they begin to ask to get down. This is the immediate situation that might lead some parents to pay particular attention to the toddler’s demands, which they evaluate as unreasonable, giving rise to feelings of anger, sweaty palms, and a stream of increasingly irritable comments to the toddler.

But the story of the parent’s emotion does not end here, because one of the sometimes-wonderful and sometimes-awful things about being human is that we are capable of metacognition. This means that our overwhelmed parent is not only becoming angry with the toddler but may also notice the fact that they are getting angry and evaluate this growing anger negatively, leading to further feelings (perhaps of guilt) along with new facial and behavioral responses, such as trying to make amends by offering the child a treat from the candy aisle.

2.1.2 Related Constructs

One point of confusion when considering emotions is how they relate to other emotion-like concepts. We find it helpful to view emotions as one cluster of instances of the broader category marked by the term affect, which refers to states that involve relatively quick good-for-me/bad-for-me discriminations. Affective states include (1) emotions such as happiness or anger, (2) stress responses in situations that exceed an individual’s ability to cope, (3) moods such as euphoria or depression, and (4) impulses to approach or withdraw.

Although there is little consensus as to how these various flavors of affect differ from one another, several broad distinctions may be usefully drawn. Thus, although both stress and emotions typically involve whole-body responses to situations that the individual sees as being relevant to their goals, stress generally refers to stereotyped responses to negative situations, whereas emotion refers to more specific responses to negative as well as positive situations. With respect to the distinction between emotions and moods, moods can often be described as being more diffuse compared to emotions. They last longer than emotions and are less likely to have well-defined and easily identifiable triggers (Frijda, Reference Frijda, Lewis and Haviland1993; Schiller et al., Reference Schiller, Yu, Alia-Klein, Becker, Cromwell, Dolcos, Eslinger, Frewen, Kemp, Pace-Schott, Raber, Silton, Stefanova, Williams, Abe, Aghajani, Albrecht, Alexander, Anders and Lowe2022). Thus, it makes sense to talk about being in a horrible mood last week, when throughout the week you were gripped by a mood that seemed to permeate your mind and body and led you to take a particularly dim view of your life and everything in it. Finally, affective impulses are perhaps the least well defined of these terms, but they are generally thought to include impulses to eat (or expel) food or drink, to exercise (or to continue to sit on the couch), or to spend time with one’s child (or to hide in the bathroom).

All four of these types of affective states can be experienced in solitary or in social contexts. In fact, it has been argued that the vast majority of our affective experiences occur in the presence of others (Boiger & Mesquita, Reference Boiger and Mesquita2012; Scherer et al., Reference Scherer, Summerfield and Wallbott1983). In this chapter, we largely focus on emotions that take place in interpersonal contexts. But many of the distinctions that are useful when thinking about emotions also apply to other types of affect (Uusberg et al., Reference Uusberg, Suri, Dweck, Gross, Neta and Haas2019).

2.2 Emotion Regulation and Related Constructs

Often, our emotions (and other manifestations of affect) seem to come and go quite haphazardly. We may feel sad at one moment, and then, inexplicably, we are cheerful at another. However, affective scientists have generally come to the conclusion that, despite the impression that emotions operate outside our control, we do often have at least some degree of control over how our emotions (and other types of affect) play out over time.

2.2.1 Core Features of Emotion Regulation

Different scholars have expressed quite different views as to how (and whether) emotion reactivity and emotion regulation should be distinguished (Gross & Feldman Barrett, Reference Gross and Feldman Barrett2011). We propose that emotion regulation requires that (1) an emotion is evaluated as either good or bad and (2) this evaluation activates a goal to change the intensity, duration, type, or consequences of the emotion in question (Gross et al., Reference Gross and Feldman Barrett2011). With regard to the evaluation of an emotion as good or bad, emotion regulation can be conceptualized as a functional coupling of two valuation systems. In this formulation, a first-level valuation system takes the situation (e.g. a fussy toddler) as its object and gives rise to the emotion (e.g. irritation). This first-level system then becomes the object of a second-level valuation system, which leads to the metacognitive evaluation of the emotion itself as either good or bad (e.g. as when we feel bad about feeling irritated with our toddler) (Figure 2.2; Gross, Reference Gross2015). In our view, it is this second-level valuation of a first-level emotion that creates the context in which emotion regulation may arise via the activation of an emotion regulation goal.

Figure 2.2 First-level and second-level valuation systems

Note. Emotion regulation involves the functional coupling of two valuation systems, in which a first-level valuation system that is instantiating emotion (Figure 2.1) becomes the object of a second-level valuation system that takes the emotion as its object (Gross, Reference Gross2015). S = situation, A = attention, E = evaluation, R = response.

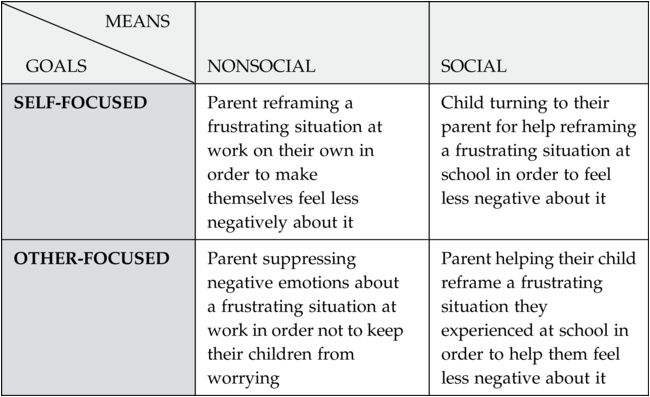

The goals that drive emotion regulation can be broadly subdivided into self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals. One note on this distinction: one of us has previously referred to this distinction as between intrinsic and extrinsic emotion regulation (Gross, Reference Gross2015). However, we now prefer the self-focused and other-focused terminology as it avoids any potential confusion with motivational meanings of the terms intrinsic and extrinsic.

When a person’s second-level valuation system takes as its object a first-level valuation system that is active within that same person – in other words, when a person engages in regulation with the intention of changing their own emotions – such regulation is considered self-focused (Gross, Reference Gross2015). Engaging in deep breathing when feeling irritated at one’s toddler, looking away from a scary movie scene, confiding in a friend after a disappointing career setback, and eating a bowl (or a tub) of ice cream to lift one’s spirits after a romantic breakup are all examples of self-focused regulation. In contrast, when the second-level valuation system takes as its object the first-level valuation system of another person – in other words, when a person engages in regulation with the intention of changing someone else’s emotions – such regulation is considered other-focused (see Figure 2.3; Nozaki & Mikolajczak, Reference Nozaki and Mikolajczak2020). For example, a parent who intentionally diverts a child’s attention away from being stuck in an over-lit and crowded grocery store during nap time and a person who helps their friend reappraise a disappointing career setback are both engaging in other-focused regulation.

Figure 2.3 Other-focused emotion regulation

Note. One of the two valuation systems that define emotion regulation is active in one person (person X on the left, in whom the second-level valuation system is active) and the other valuation system is active in another person (person Y on the right, in whom the first-level valuation system is active). In this dyad, person X activates the goal to modify person Y’s emotion.

It is estimated that most emotion regulation episodes take place in social contexts (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Richards, John, Snyder, Simpson and Hughes2006). As a result, both self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals can be attained through nonsocial as well as social means. Regulation through nonsocial means refers to processes whereby an individual takes steps to change their own (self-focused nonsocial) or someone else’s (other-focused nonsocial) emotions without assistance from other people. In contrast, regulation through social means refers to processes whereby an individual takes steps to change their own (self-focused social) or someone else’s (other-focused social) emotions in a way that directly engages the cognitive, attentional, or behavioral resources of at least one other individual (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Examples of two categories of regulatory goals (self-focused and other-focused) accomplished via two categories of regulatory means (non-social and social)

| MEANS | NONSOCIAL | SOCIAL |

|---|---|---|

| GOALS | ||

| SELF-FOCUSED | Parent reframing a frustrating situation at work on their own in order to make themselves feel less negatively about it | Child turning to their parent for help reframing a frustrating situation at school in order to feel less negative about it |

| OTHER-FOCUSED | Parent suppressing negative emotions about a frustrating situation at work in order not to keep their children from worrying | Parent helping their child reframe a frustrating situation they experienced at school in order to help them feel less negative about it |

2.2.2 Related Constructs

Paralleling the distinctions between emotions and other types of affective responses, emotion regulation can be seen as a special case of the broader category of affect regulation. This category includes (1) emotion regulation, (2) coping, (3) mood regulation, and (4) impulse regulation (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross, Thompson and Gross2007). Much of our goal-directed behavior can be construed as maximizing pleasure or minimizing pain, and thus falling under the umbrella of affect regulation in the broad sense. It can be useful to sharpen the focus by examining a few of these regulatory processes in greater detail.

Coping can be distinguished from emotion regulation both by its principal focus on decreasing negative affect and by its emphasis on longer time periods (e.g. coping with the challenge of having a child who has special needs). As noted previously, moods are typically of longer duration than emotions and are less likely to involve responses to specific “objects.” In part due to their less well-defined behavioral response tendencies, compared to emotion regulation, mood regulation is typically more concerned with altering one’s feelings rather than behavior. Impulse regulation broadly refers to the regulation of appetitive and defensive impulses (e.g. to opt for a slice of cake instead of fruit salad or to back out of giving a presentation in front of a large audience). One form of impulse regulation that has attracted particular attention is self-control (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016). Although the distinctions we have drawn here can be helpful in orienting to relevant literature, there is growing evidence that affect regulation processes may share a number of features despite the differences in their regulatory targets (for an integrative affective regulation perspective, see Gross et al., Reference Gross, Uusberg and Uusberg2019).

Another important distinction can be drawn between emotion regulation and other processes that may lead to incidental changes in one’s emotional experience. Consider, for example, a high-schooler who received the sad news that he did not get into his dream college just moments before going to a friend’s birthday party. The mere presence of other people at the party might help ameliorate his sadness even if neither he nor his friends had a goal (explicit or implicit) to do so. This phenomenon has been referred to as social affect modulation (Coan et al., Reference Coan, Schaefer and Davidson2006; Zaki & Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013). What sets emotion regulation apart from these more incidental forms of modulation is that emotion regulation is necessarily goal directed.

2.3 The Process Model of Emotion Regulation

One widely used framework for studying emotion regulation is the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, Reference Gross1998, Reference Gross2015). This framework delineates four stages of emotion regulation: identification, selection, implementation, and monitoring (Figure 2.4). Each stage culminates in a decision (conscious or otherwise) that the regulator makes and that propels them toward their emotional goals (Braunstein et al., Reference Braunstein, Gross and Ochsner2017; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Uusberg and Uusberg2019; Koole et al., Reference Koole, Webb and Sheeran2015). The four decisions that correspond to the four stages of regulation are (1) whether to regulate, (2) what strategies to use in order to regulate, (3) how to implement said strategies under the circumstances, and (4) whether to modify one’s ongoing emotion regulation efforts in any way (e.g. by selecting a different strategy or discontinuing regulation altogether).

Figure 2.4 Process model of emotion regulation

Note. According to the process model of emotion regulation, four stages define emotion regulation. The first three of these correspond to the second-level valuation steps of attention, evaluation, and response. The fourth is the monitoring stage. Five families of emotion regulation strategies may be distinguished based on where they have their primary impact on emotion generation: situation selection, situation modification, attentional strategies, cognitive change, and response modulation.

One advantage of the process model is that it can be used to describe both self-focused and other-focused emotion regulation attained via both nonsocial as well as social means (i.e. all cells in Table 2.1). In a two-person interaction, both partners can perceive their own emotional states. These perceptions provide input into the four stages of self-focused emotion regulation. In addition to perceiving their own emotions, both parties can also form dynamic mental representations of each other’s emotional states. These representations feed into the four stages of other-focused emotion regulation that mirror those of self-focused regulation. Whatever the partners’ emotional goals may be, their decisions at each stage can also lead them to pursue such goals via nonsocial or social means (Figure 2.5). In the following sections, we consider the four stages of emotion regulation and illustrate how the process model can be usefully applied to instances of social and nonsocial emotion regulation.

Figure 2.5 Other-focused regulation accomplished via social means

Note. Panel A: person X directly regulating person Y’s emotion. Panel B: person X encouraging person Y to regulate Y’s emotion.

2.3.1 The Identification Stage

At the identification stage, the regulator identifies a gap between the actual (or projected) and desired emotional state (i.e. the emotion goal) and decides whether to take action to shrink that gap. If the gap in question is between the regulator’s own experienced and desired emotional states, the decision to take action would set in motion self-focused regulation. If, on the other hand, the gap in question is between the regulator’s representation of another person’s emotional state and the emotional state that the regulator wants to see enacted in the other person instead, the result will be other-focused regulation. In the case of other-focused regulation, the regulator may come to the decision to regulate independently (e.g. by noticing another person’s angry demeanor) or as a result of a direct request for regulatory assistance.

Often, desired emotional states are the ones that maximize pleasure and minimize displeasure (e.g. happiness, contentment). But people can also value other aspects of emotional states (e.g. motivational), leading them to desire emotional states that are useful but not particularly pleasant (or even patently unpleasant; Ford & Gross, Reference Ford and Gross2019; Tamir, Reference Tamir2016). For example, a parent might scold their child for hitting their sibling in order to upregulate the child’s feelings of guilt and deter them from committing similar transgressions in the future. In this case, the parent views guilt as a desired emotional state (because of its high motivational value) despite the fact that it can also be an extremely unpleasant emotion to experience. This is an example of what is called counterhedonic emotion regulation (Zaki, Reference Zaki2020). Note that, in the case of other-focused regulation, the desired state may be determined by the regulator’s beliefs about the target’s goals, the regulator’s goals that are independent from (and that might even go against) those of the target, or some combination of the two.

2.3.2 The Selection Stage

A decision to change an emotional state triggers the selection stage, which is when the regulator decides where to intervene in the emotion-generative process. Five families of emotion regulation strategies may be distinguished based on the stage of emotion generation at which they have their primary impact (Figure 2.4). Situational selection seeks to alter emotion by selecting which emotion-eliciting situations are encountered or avoided. Situation modification works by modifying how such situations unfold once encountered (situation modification). Attentional strategies seek to alter emotion by changing what aspects of the situation one pays attention to. Cognitive strategies seek to alter emotion by modifying the cognitive representations of the situations (i.e. interpretations) or one’s goals. Finally, response modulation strategies seek to alter emotions by directly modifying emotion-related experiential, behavioral, or physiological responses.

Emotion regulation strategies are not inherently adaptive or maladaptive but rather can be relatively well suited or ill suited for particular situations at particular times (Bonanno & Burton, Reference Bonanno and Burton2013; Sheppes, Reference Sheppes2020). Thus, strategy selection can be thought of as the process of matching strategies to one’s emotional goals and situational demands on the basis of their costs and benefits. For example, where an upsetting situation can be improved, it may be best to change the situation rather than to use cognitive strategies. By contrast, in a context where little can be done to improve the situation, it may be best to use cognitive rather than situational strategies (Troy et al., Reference Troy, Shallcross and Mauss2013).

In addition to deciding what strategies to use, the regulator at the selection stage must also weigh the costs and benefits of relying on nonsocial versus social regulatory resources. Thus, for example, in addition to deciding that the best course of action is to change the upsetting situation, the regulator must also decide if they wish to change the situation on their own or with some degree of assistance from their interaction partner or some other person.

2.3.3 The Implementation Stage

Strategy selection triggers the implementation stage, during which the regulator decides which specific actions to take as part of their chosen strategy. This stage is needed because the broad strategies that aim to alter one or more of the steps in the emotion-generative process that were outlined previously can be enacted in different ways. These are referred to as regulation tactics. The implementation stage is where the regulation process impacts the emotion by translating the blueprint of a general regulation strategy (e.g. cognitive change) into specific mental or physical actions (e.g. thinking that someone who bumped into me wasn’t trying to hurt me, but instead had tripped). The implementation stage is also where the partners in a multiperson regulatory interaction decide how exactly to divide the regulatory labor. Thus, for example, a parent engaged in other-focused regulation of an upset child must decide whether to offer concrete suggestions for how the situation can be reinterpreted or to take on a more passive role by encouraging the child to come up with a reinterpretation on their own.

2.3.4 The Monitoring Stage

The identification, selection, and implementation decisions form an iterative cycle. As the situation evolves over time, each of these decisions may need to be updated accordingly. This updating process can be viewed as a separate monitoring stage, involving a decision to maintain, switch, or stop the regulation attempt. As long as the regulation attempt continues to produce the desired results, the person can maintain regulation by relying on the existing identification, selection, and implementation decisions. However, if emotion doesn’t change, or changes in undesirable ways, the chosen selection and/or implementation decisions can be switched, or the regulation attempt can be stopped altogether. Switching or stopping may also be necessitated by a change in context, which provides a new set of affordances or barriers to regulation.

2.4 Interpersonal Emotion Regulation

As we have made clear, the process model of emotion regulation provides a framework for considering both self- and other-focused emotion regulation that employs either social or non-social means (see Table 2.1). However, particularly in the context of a discussion of emotion regulation in parenting, the nature of the context in which regulation takes place deserves elaboration.

The growing recognition that emotion regulation often takes place in social contexts has led to an explosion of interest in interpersonal emotional regulation (Nozaki & Mikolajczak, Reference Nozaki and Mikolajczak2020; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Morelli, Ong and Zaki2018; Zaki & Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013). Despite the growing enthusiasm, to date, there remains little consensus on where exactly non-interpersonal emotion regulation ends and interpersonal emotion regulation begins. The term interpersonal emotion regulation has been used to refer to a range of interconnected yet distinct processes, including, for example: (1) Claire asking for Jordan’s help to regulate her emotions, (2) Jordan regulating Claire’s emotions, and (3) Jordan regulating his own emotions with the goal of changing Claire’s emotions. Here, we propose a broad definition of interpersonal emotion regulation that includes all three of the aforementioned examples and encompasses all instances of emotion regulation that directly involve two or more individuals, as a result of activation of other-focused regulatory goals, reliance on social regulatory means, or both.

There are several features of interpersonal emotion regulation that are not present in non-interpersonal regulation and that may be particularly important to consider in connection to parenting. First, self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals can be co-activated in interpersonal emotion regulation. That is, a person may be driven by the goal of changing their own and someone else’s emotions simultaneously in the course of a single regulatory interaction. Consider, for example, a parent who distracts their child from a scary movie scene. The parent’s use of an attentional strategy to change the child’s emotions may double as a situational strategy aimed at accomplishing the parent’s self-focused goal to avoid the frustration of having to disrupt a relaxing movie night to console a scared child. In this case, the parent’s other-focused regulatory goal (i.e. to help the child feel calmer) is subordinate to their self-focused regulatory goal (i.e. to enjoy a relaxing evening). The two types of goals can also be co-activated nonhierarchically. For instance, a father whose children are worried about their mother’s upcoming surgery may talk to them about the low risks associated with the procedure in order to quell the children’s as well as his own anxieties at the same time.

Another important consideration has to do with the fact that the degree to which the partners in an interpersonal regulatory interaction are involved in the regulation process may also vary across and within situations. For example, in the case where a daughter seeks out her mother’s advice for dealing with a stressful situation at school, regulation of the daughter’s emotions can be accomplished by a joint recruitment of the daughter’s and the mother’s regulatory resources. But what specific resources are used and how the regulatory labor gets divided (i.e. how a general strategy is implemented through a series of concrete steps) can vary a great deal from one situation to another. For example, the mother could come up with a suggestion for how her daughter could reappraise the situation in a way that would make it appear less stressful. However, the success of any such reappraisal attempt would ultimately depend on the daughter’s willingness and ability to implement that reappraisal. Alternatively, the mother could take direct action to intervene in the situation, changing it in a way that would result in reduction of her daughter’s negative emotions with little or even no direct involvement from the daughter herself. This balance might also shift dynamically as both parties monitor their progression toward their respective regulatory goals and make the necessary adjustments. Gaining a better understanding of the interpersonal and temporal dynamics of this regulatory “dance” is a critical goal for future research in this area.

The degree to which individuals rely on nonsocial versus social means to accomplish their regulatory goals varies not only across situations but also across development. One category of interactions in which regulation may be achieved entirely through social means includes caregivers’ regulation of infants’ affect (e.g. through physical touch). Infants must rely on their caregivers’ regulatory resources before they can develop the capacity for independent self-regulation (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Michel and Teti1994). Thus, the development of emotion regulation across childhood can be thought of as the scaffolding process whereby parents’ child-focused regulation that relies exclusively on parental resources gradually turns into the child’s own self-focused regulation that draws on more and more of the child’s own resources as they grow older.

Finally, it bears noting that all our examples up to this point have focused on unilateral interpersonal regulation in parent-child dyads. However, interpersonal co-regulation – in which both parties are regulating each other’s emotions (with or without regulating their own emotions at the same time) – as well as interactions that involve more than two partners are exceedingly common in familial contexts. Even a seemingly straightforward and lighthearted discussion of a child’s recent athletic accomplishment around the dinner table may involve complex interactions of multiple valuation systems and regulatory paths (Figure 2.6). The parents need to coordinate regulatory resource allocation as they take turns upregulating the child’s positive emotions and ensuring that their sibling does not feel jealous or left out, all the while trying to prevent their own negative emotions from a less-than-satisfying day at work from spilling over into the precious family time. The task of drawing an accurate “map” of a regulatory interaction grows exponentially with increasing numbers of participants and co-active goals. Finding ways to represent and study the complexity that is inherent in interpersonal emotion regulation is a critical goal for basic and applied research in this area.

Figure 2.6 Multiperson, multigoal, multimean interpersonal emotion regulation

Note. In this example, Parent X is regulating Child X’s, Parent Y’s, and their own emotions. Parent Y is regulating Parent X’s, Child X’s, and Child Y’s emotions. Child X is experiencing an emotion that Parent X and Parent Y are regulating. Child Y is regulating their own emotion with assistance from Parent Y.

2.5 Parental Influences on Children’s Emotion Regulation

Children learn to recognize, express, and regulate their emotions in part through interactions with primary caregivers and other important figures in their lives (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Michel and Teti1994; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998). The tripartite model of familial influences on children’s emotion regulation (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007) describes three interrelated yet conceptually distinct mechanisms through which parents influence children’s emotion regulation: (1) observation, which refers to children’s modeling of parents’ own emotion regulation; (2) emotion-related parenting practices, such as caregivers’ reactions to children’s emotional expressions and explicit coaching in emotion regulation; and (3) emotional climate of the family, which includes overall warmth, cohesion, and patterns of emotional expressions within the family. All three of these mechanisms may shape the development of children’s ability to identify the need to regulate, select, and implement appropriate regulatory strategies, and to flexibly adjust their regulatory efforts in the face of changing internal emotional needs and external situational demands.

2.5.1 Observation

Observational learning is an important mechanism of skill acquisition early in life (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977), and skills related to emotion regulation are no exception. Children as young as 4 years of age mimic their mothers’ use of emotion regulation strategies (Bariola et al., Reference Bariola, Hughes and Gullone2012; Silk et al., Reference Silk, Shaw, Skuban, Oland and Kovacs2006). Thus, observation might play a role in shaping the decisions that children make during the selection and implementation stages of the emotion regulation process. Strategies that are frequently used by a child’s parents are more likely to become a part of the child’s own regulatory repertoire. In addition, by observing how one’s parents respond to different emotion-eliciting situations children might also learn to pair specific strategies (and tactics) with circumstances in which they are commonly used by the parents. For example, a child who repeatedly observes their parents turn to each other for emotional support while dealing with challenges at work may be more likely to seek out others’ support when faced with problems at school.

2.5.2 Parenting Practices

Caregivers are the main drivers of children’s emotional socialization, which is a process whereby children develop an understanding of their own and others’ emotions, their sources, and the norms surrounding their expression (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998). Parents’ reactions to children’s emotional expressions and discussion of emotion-related topics may play a particularly important role in shaping children’s ability to identify when their emotions need regulating. Consistent with this perspective, children whose parents validate their emotions and help them label those emotions tend to express less negative affect and show better emotion regulation ability (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998; Gottman et al., Reference Gottman, Katz and Hooven1996; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Morris, Steinberg, Aucoin and Keyes2011). When it comes to what emotion regulation strategies parents teach to their children, there is evidence that it depends, in large part, on what strategies the parents themselves use to regulate their own emotions. For example, parents who engage in more suppression and rumination are also more likely to encourage their children to suppress and ruminate, whereas parents who use more problem-solving and reappraisal tend to facilitate the use of the same strategies in their children (Cohodes et al., Reference Cohodes, Preece, McCauley, Rogers, Gross and Gee2022). Thus, direct parental assistance with children’s emotion regulation has the potential to further reinforce children’s learning of strategy selection that takes place through observation.

Importantly, by observing how their parents talk to them about emotions and emotion-related topics, children also form their own beliefs about emotions (e.g. the extent to which emotions are helpful or harmful and how much – if at all – one’s emotions can be changed). There is a growing consensus in the field that people’s beliefs about emotions play an important role in shaping their decisions at all four stages of the emotion regulation process (Ford & Gross, Reference Ford and Gross2019). Understanding how such beliefs develop in the context of child–caregiver interactions is a critical goal for future research in this area.

2.5.3 Emotional Climate

The importance of warm and nurturing early family environments for later-life emotion regulation is well established in the literature (Petrova et al., Reference Petrova, Nevarez, Rice, Waldinger, Preacher and Schulz2021; Repetti et al., Reference Repetti, Taylor and Seeman2002; Waldinger & Schulz, Reference Waldinger and Schulz2016). Warm and responsive parenting styles that promote secure patterns of attachment have been linked to more adaptive emotion regulation across a number of studies (Brumariu, Reference Brumariu2015). In contrast, adverse early environments characterized by frequent experiences and expressions of negative emotions are consistently linked with less adaptive regulation (Miu et al., Reference Miu, Szentágotai-Tătar, Balázsi, Nechita, Bunea and Pollak2022). In more severe cases, child maltreatment and the ensuing difficulties in emotion regulation may even put individuals at higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders later in life (Bertele et al., Reference Bertele, Talmon, Gross, Schmahl, Schmitz and Niedtfeld2022), perpetuating cycles of maladaptive emotion regulation well into adulthood.

Negative emotional climate and early adversity have been linked to long-term deficits in emotional awareness and understanding (Dunn & Brown, Reference Dunn and Brown1994; Hébert et al., Reference Hébert, Boisjoli, Blais and Oussaïd2018; Petrova et al., Reference Petrova, Nevarez, Rice, Waldinger, Preacher and Schulz2021). Such deficits might exert especially detrimental effects on the development of children’s ability to monitor their affective, behavioral, and physiological responses and fine-tune their regulatory efforts to adapt to changing situational and internal demands. Consistent with this possibility, recent work demonstrates a robust association between alexithymia – a trait that involves difficulties identifying and describing emotions – and difficulties with emotion regulation (Preece et al., Reference Preece, Mehta, Becerra, Chen, Allan, Robinson, Boyes, Hasking and Gross2022). In line with these findings, evidence from longitudinal research points to alexithymia as a possible mechanism connecting early maltreatment to later-life emotional distress (Hébert et al., Reference Hébert, Boisjoli, Blais and Oussaïd2018). Negative emotional climate may also indirectly shape the development of children’s emotion regulation via pathways related to both observation and parenting practices, since parents in less emotionally nurturing households may be more likely to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies themselves.

Taken together, these findings underscore the need for further research that would deepen our understanding of the interplay among observational learning, parenting practices, and emotional climate and their joint roles in shaping the development of emotional awareness and emotion regulation from infancy and childhood through adulthood and into older age.

2.6 Concluding Comment

From the exhilaration that comes with stepping into the caregiver role for the first time to the everyday reality of getting up six times a night to calm down a fussy infant, opportunities for emotion regulation are never in short supply when it comes to parenting. Our aim in this chapter was to provide a broad overview of emotion regulation as it unfolds in both non-interpersonal and interpersonal contexts, with particular attention to topics related to parenting. To this end, we put forth a conceptual framework that distinguishes between self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals as well as nonsocial and social regulatory means. We have argued that emotion regulation can be fruitfully understood as a four-stage process during which individuals make a series of decisions about whether and how to change their emotions and dynamically adjust their regulatory efforts to changing situational demands. This framework can serve as a useful tool for integrating the literatures on parenting and emotion regulation. We hope that this chapter will be useful to scholars in parenting psychology and related domains, and that it will inspire future research on emotion regulation in self and others.